Clay Greene on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

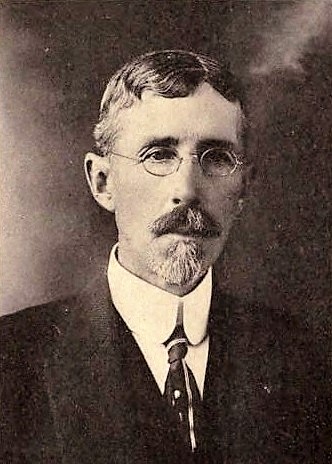

Clay Meredith Greene (March 12, 1850 – September 5, 1933) was an American screenwriter, theatre critic and journalist, but he was chiefly known as a dramatist. He was often referred to as either the "first American" or "first white American child" born in San Francisco, a claim spread by Greene himself. A graduate of

Clay Meredith Greene was born on March 12, 1850, in

Clay Meredith Greene was born on March 12, 1850, in

In 1878 Greene moved to New York City, where, by 1879, he had established himself as a journalist and playwright. There he had his most active years as a dramatist, becoming well known among the literary establishment, including befriending

In 1878 Greene moved to New York City, where, by 1879, he had established himself as a journalist and playwright. There he had his most active years as a dramatist, becoming well known among the literary establishment, including befriending

Greene wrote the book of the musical ''Peti, the Vagabond'', which starred Hubert Wilke in the title role and premiered at the California Theatre in San Francisco in 1890. He co-authored the 1892 play ''The New South'' with actor

Greene wrote the book of the musical ''Peti, the Vagabond'', which starred Hubert Wilke in the title role and premiered at the California Theatre in San Francisco in 1890. He co-authored the 1892 play ''The New South'' with actor

Greene wrote the lyrics to the musical '' Aunt Hannah'', which premiered on Broadway at the Bijou Theatre in February 1900. This musical featured Greene's most successful song, "My Tiger Lily" (or "Ma Tiger Lily"). A month later, a second Broadway musical with a book by Greene, ''The Regatta Girl'', was staged at Koster & Bial's Music Hall. When Broadway producer John C. Fisher decided to bring the 1901 English musical ''The Silver Slipper'' to the United States for the first time, he had Greene Americanize the musical's original book by

Greene wrote the lyrics to the musical '' Aunt Hannah'', which premiered on Broadway at the Bijou Theatre in February 1900. This musical featured Greene's most successful song, "My Tiger Lily" (or "Ma Tiger Lily"). A month later, a second Broadway musical with a book by Greene, ''The Regatta Girl'', was staged at Koster & Bial's Music Hall. When Broadway producer John C. Fisher decided to bring the 1901 English musical ''The Silver Slipper'' to the United States for the first time, he had Greene Americanize the musical's original book by

Greene returned to California after the death of his first wife, Alice Randolph Greene (née Wheeler), in 1910, and his subsequent marriage six months later to his second wife, the playwright Laura H. Robinson, in 1911. Greene had previously collaborated on several plays with Robinson and was 60 years old when he remarried. Financial problems prompted Greene to sell his

Greene returned to California after the death of his first wife, Alice Randolph Greene (née Wheeler), in 1910, and his subsequent marriage six months later to his second wife, the playwright Laura H. Robinson, in 1911. Greene had previously collaborated on several plays with Robinson and was 60 years old when he remarried. Financial problems prompted Greene to sell his

While visiting Los Angeles, Greene suffered from a

While visiting Los Angeles, Greene suffered from a

*''The Fiancee and the Fairy'' (1913)

*''A Waif of the Desert'' (1913)

*''Forgiven; or, the Jack of Diamonds'' (1914)

* ''

*''The Fiancee and the Fairy'' (1913)

*''A Waif of the Desert'' (1913)

*''Forgiven; or, the Jack of Diamonds'' (1914)

* ''

Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University is a private university, private Jesuit university in Santa Clara, California, United States. Established in 1851, Santa Clara University is the oldest operating institution of higher learning in California. The university' ...

(SCU), Greene was the author of the Passion Play

The Passion Play or Easter pageant is a dramatic Play (theatre), presentation depicting the Passion of Jesus: his Sanhedrin Trial of Jesus, trial, suffering and death. The viewing of and participation in Passion Plays is a traditional part of L ...

''Nazareth'' which was written for and staged as part of the 50th anniversary celebration of the founding of SCU in 1901. The play was performed repeatedly every three years at SCU during Greene's lifetime.

He began his professional life as a stockbroker and journalist. With his brother Harry Ashland Greene, he co-founded the brokerage firm Greene & Company. While working in that field, he began writing plays, his first being ''Struck Oil

''Struck Oil'' is an 1874 play set during the American Civil War and a 1919 Australian silent film, now considered lost. The play, which introduced Maggie Moore to Australian theatre-goers, was popular with the Australian public and the basis o ...

'' (1874). By 1878 Greene had moved to New York City, where he was soon working as both a playwright and journalist. He and his wife lived in a home in Bayside, Queens

Bayside is a neighborhood located in the New York City borough of Queens. It is bounded by Whitestone to the northwest, the Long Island Sound and Little Neck Bay to the northeast, Douglaston to the east, Oakland Gardens to the south, and Fr ...

, for approximately thirty years. He wrote an estimated 80 plays and musicals, several of which were staged on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

. His plays brought him wealth and popular celebrity during his lifetime, but none of his works endured after his death.

With playwright Steele Mackaye

James Morrison Steele MacKaye ( ; June 6, 1842 – February 25, 1894) was an United States of America, American playwright, actor, theater manager and inventor. Having acted, written, directed and produced numerous and popular plays and theatric ...

, Greene co-founded the American Dramatic Author's Society in 1878, the first U.S. organization dedicated to protecting the rights of dramatists. He served as the president of the New York City arts social club The Lambs

The Lambs, Inc. (also known as The Lambs Club) is a New York City social club that nurtures those active in the arts, as well as those who are supporters of the arts, by providing activities and a clubhouse for its members. It is America's old ...

(called "The Shepherd") from 1891 to 1898, and again from 1902 to 1906. Financial problems forced him to sell his estate on Long Island not long after he married his second wife in 1911, when he moved back to San Francisco. From 1913 to 1916 he worked as a screenwriter for the Lubin Manufacturing Company

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was an American motion picture production company that produced silent films from 1896 to 1916. Lubin films were distributed with a Liberty Bell trademark.

*

*

History

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was forme ...

, also occasionally as an actor on camera and as a film director. He remained in San Francisco until his death in 1933.

Early life and education

Clay Meredith Greene was born on March 12, 1850, in

Clay Meredith Greene was born on March 12, 1850, in San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, to William Harrison Greene and his wife Anne Elizabeth Fisk. Some sources claim he was the "first American born in San Francisco", although his obituary in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' was careful to point out that he was born six months before the California Statehood Act

The California Statehood Act, officially An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union and also known as the California Admission Act, is the federal legislation that admitted California to the United States as the thirty-f ...

. This assertion originated with Greene himself, who claimed that he was "the first American white child born in San Francisco". While it is possible that he was the first white child born in San Francisco when it was a mining supply camp in 1850, the historicity of this claim was questioned by reporters, who pointed out that white children were likely born at the Mission San Francisco de Asís

The Mission San Francisco de Asís (), also known as Mission Dolores, is a historic Catholic Church, Catholic church complex in San Francisco, San Francisco, California. Operated by the Archdiocese of San Francisco, the complex was founded in ...

much earlier, during the Spanish colonial period. Greene was the grandson of Squire Fiske, who served as a first lieutenant in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment (also known as Varnum's Regiment, the 9th Continental Regiment, the Black Regiment, the Rhode Island Regiment, and Olney's Battalion) was a regiment in the Continental Army raised in Rhode Island during the Amer ...

during the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. As his descendant, Greene was an active member of the Sons of the American Revolution

The Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), formally the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (NSSAR), is a federally chartered patriotic organization. The National Society, a nonprofit corporation headquartered in Louisvi ...

.

Clay grew up in a house his father built on San Francisco's Telegraph Hill A telegraph hill is a hill or other natural elevation that is chosen as part of an optical telegraph system.

Telegraph Hill may also refer to:

England

* A high point in the Haldon Hills, Devon

* Telegraph Hill, Dorset, a hill in the Dorset Downs ...

. As a child, he was enthralled by the theatre business that blossomed in San Francisco during the California gold rush

The California gold rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the U ...

. As a teenager he became a regular theatregoer, and he both acted in and wrote amateur burlesques

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

and other plays. He was educated at the College of California

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary education, tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding academic degree, degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further educatio ...

(now University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

), when it was located in Oakland, California

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, California, Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major We ...

. At that time the school was a college preparatory school, so Greene did not earn a university diploma from that institution. He did however attend City College of San Francisco

City College of San Francisco (CCSF or City College) is a public community college in San Francisco, California, United States. Founded as a junior college in 1935, the college plays an important local role, enrolling as many as 1 in 35 San Franc ...

and Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University is a private university, private Jesuit university in Santa Clara, California, United States. Established in 1851, Santa Clara University is the oldest operating institution of higher learning in California. The university' ...

(SCU), earning a degree from SCU. His parents sent Clay to SCU in 1867, encouraging him pursue a career in medicine or law, but his university education only increased his interest in theatre.

Clay returned to his native San Francisco in 1870, where he worked as a journalist and as a stock broker. He initially worked on his own, but eventually he partnered with his younger brother, Harry Ashland Greene. The two co-founded the stock brokerage firm Greene & Company. While working as a stock broker and journalist, he continued to write plays and act, including performing the role of Dick Deadeye in the comic opera

Comic opera, sometimes known as light opera, is a sung dramatic work of a light or comic nature, usually with a happy ending and often including spoken dialogue.

Forms of comic opera first developed in late 17th-century Italy. By the 1730s, a ne ...

''H.M.S. Pinafore

''H.M.S. Pinafore; or, The Lass That Loved a Sailor'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and a libretto by W. S. Gilbert. It opened at the Opera Comique in London on 25 May 1878, and ran for 571 performances, w ...

'' at San Francisco's Standard Theater.

Playwright

Between the years 1874 and 1925, Greene wrote approximately eighty plays, opera libretti, and musicals (book, lyrics or both). He was one of a group of American playwrights who emerged during the 1870s, includingAugustin Daly

John Augustin Daly (July 20, 1838 – June 7, 1899) was one of the most influential men in American theatre during his lifetime. Drama critic, theatre manager, playwright, and adapter, he became the first recognized stage director in America. He ...

, Bronson Howard

Bronson Crocker Howard (October 7, 1842 – August 4, 1908) was an American dramatist.

Biography

Howard was born in Detroit where his father Charles Howard was Mayor in 1849. He prepared for college at New Haven, Conn., but instead of ente ...

, James J. McCloskey Jr., and Thomas Blades de Walden, that provided a new surge of popular melodrama

A melodrama is a Drama, dramatic work in which plot, typically sensationalized for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodrama is "an exaggerated version of drama". Melodramas typically concentrate on ...

s and comedies to the American theatre. In 1878 Greene and playwright Steele Mackaye

James Morrison Steele MacKaye ( ; June 6, 1842 – February 25, 1894) was an United States of America, American playwright, actor, theater manager and inventor. Having acted, written, directed and produced numerous and popular plays and theatric ...

co-founded the American Dramatic Author's Society, the first organization in the United States created to protect the rights of dramatists. It was short lived, and was supplanted by a series of other short lived organizations, until the Dramatists Guild of America

The Dramatists Guild of America is a professional organization for playwrights, composers, and lyricists working in the U.S. theatre market. It was born in 1921 out of the Authors Guild, known then as Authors League of America, formed in 1912.

M ...

was formed in 1919.

Many of Greene's plays, particularly his early and late ones, were first staged in his native San Francisco. Three of his successful plays were set during the California Gold Rush

The California gold rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the U ...

: ''M'liss'' (1877), based on a story by Bret Harte

Bret Harte ( , born Francis Brett Hart, August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902) was an American short story writer and poet best remembered for short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush. In a caree ...

and co-authored with A. Slason Thompson); ''Chispa'' (1882, co-authored with Thompson); and ''The Golden Giant'' (1886). During most of his career as a dramatist, however, he lived and worked in New York City. His plays were performed widely throughout the United States during his lifetime, and he achieved wealth through his work as a playwright. but none of his works remain in the Western canon

The Western canon is the embodiment of High culture, high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly cherished across the Western culture, Western world, such works having achieved the status of classics.

Recent ...

of theatre literature.

Early writing career

Greene began a journalism career in San Francisco, writing for ''The Golden Era

''The Golden Era'' was a 19th-century San Francisco newspaper. The publication featured the writing of Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Charles Warren Stoddard (writing at first as "Pip Pepperpod"), Fitz Hugh Ludlow, Adah Isaacs Menken, Ada Clare, Prent ...

'' in 1870. He also wrote for its competing paper, ''The Argonaut

''The Argonaut'' was a newspaper based in San Francisco, California from 1878 to 1956. It was founded by Frank Somers, and soon taken over by Frank M. Pixley, who built it into a highly regarded publication. Under Pixley's stewardship it was ...

''. His earliest success as a dramatist was the play ''Struck Oil

''Struck Oil'' is an 1874 play set during the American Civil War and a 1919 Australian silent film, now considered lost. The play, which introduced Maggie Moore to Australian theatre-goers, was popular with the Australian public and the basis o ...

'' which he adapted for actor J. C. Williamson from Sam Smith's play ''The Dead, or Five Years Away''. Premiered in 1874, ''Struck Oil'' became a hit for Williamson, who toured in the work in both the United States and Australia. That same year he wrote the four-act play ''The Cut Glove'' for the comic duo P. F. Baker and T. J. Farron, which they toured in the southern United States.

With A. G. Thompson, Greene co-wrote the play ''Freaks of Fortune'', which premiered at the Grand Opera House in San Francisco in 1877. Williamson acquired the rights to the work after its original successful run and brought the play to the Boston stage. Williamson and his company performed other plays by Greene at The Boston Theatre

:''See Federal Street Theatre for an earlier theatre known also as the Boston Theatre''

The Boston Theatre was a theatre in Boston, Massachusetts. It was first built in 1854 and operated as a theatre until 1925. Productions included performances ...

in 1878, including ''Struck Oil'' and ''The Chinese Question''.

Actress Kate Mayhew owned the rights to an 1873 play by Richard H. Cox based on the popular story "The Work on Red Mountain" by Bret Harte

Bret Harte ( , born Francis Brett Hart, August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902) was an American short story writer and poet best remembered for short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush. In a caree ...

, which had been serialized from 1860 to 1863. Its central figure is a feisty miner's daughter, Melissa Smith, aka "M'liss". Dissatisfied with Cox's writing, Mayhew hired Greene to substantially rewrite the play. Greene's version, titled ''M'liss'', premiered in 1877, at the New Market Theater in Old Town Historic District of Portland, Oregon, and a subsequent run immediately followed at the California Theatre in San Francisco. ''M'liss'' was well received in Portland but had a lukewarm reception in San Francisco. Mayhew asked Greene to rework the final act of the play, and he began work in late 1877, but, according to Mayhew, he ultimately abandoned this project to A. Sisson Thompson to finish, when Greene decided to leave San Francisco and relocate to New York City. Greene and Thompson copyrighted the play as ''M'liss, A Romance of Red Mountains'' in February 1878, a copyright which Mayhew disputed in court later that year.

New York City dramatist

In 1878 Greene moved to New York City, where, by 1879, he had established himself as a journalist and playwright. There he had his most active years as a dramatist, becoming well known among the literary establishment, including befriending

In 1878 Greene moved to New York City, where, by 1879, he had established himself as a journalist and playwright. There he had his most active years as a dramatist, becoming well known among the literary establishment, including befriending Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

. Greene and his first wife resided at a home in Bayside, Queens

Bayside is a neighborhood located in the New York City borough of Queens. It is bounded by Whitestone to the northwest, the Long Island Sound and Little Neck Bay to the northeast, Douglaston to the east, Oakland Gardens to the south, and Fr ...

, for thirty years until her death.

1880s

With Slauson Thompson, Greene co-authored the four actfarce

Farce is a comedy that seeks to entertain an audience through situations that are highly exaggerated, extravagant, ridiculous, absurd, and improbable. Farce is also characterized by heavy use of physical comedy, physical humor; the use of delibe ...

''Sharps and Flats'' as a starring vehicle for the comedy duo of Robson and Crane. A send-up of the speculative New York stock market and its buyers during the Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

, it premiered at the Standard Theatre on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

in 1880. Greene and Thompson collaborated on a second play, ''Chispa'', which was produced by David Belasco

David Belasco (July 25, 1853 – May 14, 1931) was an American theatrical producer, impresario, director, and playwright. He was the first writer to adapt the short story ''Madame Butterfly'' for the stage. He launched the theatrical career of ...

at the Baldwin Theater in San Francisco in 1881.

In 1883 Greene collaborated with the Hanlon Brothers acrobats on the play ''Pico; or, The legend of Castle Molfi'', later reworked as the fairy pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment, generally combining gender-crossing actors and topical humour with a story more or less based on a well-known fairy tale, fable or ...

''Fantasma'', which had a long stage life in the Hanlon Brothers repertoire. He also worked with the Hanlon Brothers that year on a revised version of their musical ''Le Voyage en Suisse''. Greene was hired to write a play for the Grand Opera House in Toronto on the life and death of Canadian politician and resistance movement leader Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis in Canada, Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of ...

, who had just been hanged on November 16, 1885. Greene rapidly produced the play, ''Louis Riel, or, The Northwest Rebellion'', and it premiered in Toronto with a cast of New York actors on New Year's Day

In the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Day is the first day of the calendar year, January 1, 1 January. Most solar calendars, such as the Gregorian and Julian calendars, begin the year regularly at or near the December solstice, northern winter ...

1886.

In 1886 Greene wrote his first original musical, ''Sybil'', with the composer John F. Mitchell. The same year his play ''The Golden Giant'' was produced by Charles Frohman

Charles Frohman (July 15, 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American theater manager and producer, who discovered and promoted many stars of the American stage. Frohman produced over 700 shows, and among his biggest hits was '' Peter Pan'', both ...

at Broadway's Fifth Avenue Theatre

The Fifth Avenue Theatre was a Broadway theatre in Manhattan, New York City, United States, at 31 West 28th Street and Broadway (1185 Broadway). It was demolished in 1939.

Built in 1868, it was managed by Augustin Daly in the mid-1870s. In ...

in a production starring McKee Rankin

Arthur McKee Rankin (1841–1914) was a Canadian born American stage actor and manager. He was the son of a member of the Canadian Parliament. After a dispute with his father he left home to become an actor. He made his stage debut in Rochester, N ...

and his wife Kitty Blanchard

Elizabeth "Kitty" Blanchard ( – December 14, 1911) was an American stage actress from Pennsylvania. A popular actress in 1870s and 1880s, she married actor McKee Rankin (1841–1914). Their children married into several other famous stage fa ...

. While successful in New York, the play was a flop on the road and lost Frohman a considerable amount of money. 1887 was highly productive for Greene, beginning with the musical play ''Hans the Boatman'', which he created for the Theatre Royal, Sheffield, in England, to start the Swiss-born English actor Charles Arnold (1854–1905), who portrayed the title character. The most successful musical of Greene's career, it was a tremendous hit for Arnold, who toured the piece for three years across Australia, Asia, and the United States. Greene also wrote the libretto to the 1887 musical ''Our Jennie'', starring Jennie Yeamans

Jennie Yeamans (born Eugenia Marguerite Yeamans; 1862 – 28 November 1906) was a child actress and singer popular in the 1870s and 1880s, and later a famous adult singer and actress. She was the younger sister of early silent film character ac ...

, which was staged on Broadway at the People's Theatre. That same year he co-authored the play ''Pawn Ticket 210'' with Belasco for Lotta Crabtree

Charlotte Mignon "Lotta" Crabtree (November 7, 1847 – September 25, 1924), also known mononymously as Lotta, was an American actress, entertainer, comedian, and philanthropist. Born in New York City and raised in the gold mining hills of North ...

; it premiered at McVicker's Theater in Chicago.

In 1888 Greene's play adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

's novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

'' premiered at the Hollis Street Theatre

The Hollis Street Theatre (1885–1935) was a theatre in Boston, Massachusetts, that presented dramatic plays, opera, musical concerts, and other entertainments.

Brief history

Boston architect John R. Hall designed the 1,600-seat theatre in 18 ...

in Boston. He served as the lyricist of the musical '' Blue Beard, Jr.'', composed by Fred J. Eustis, Richard Maddern, and John Joseph Braham Sr. It premiered at the Grand Opera House, Chicago, in 1889, and then toured nationally, including a stop on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

at Niblo's Garden

Niblo's Garden was a theater on Broadway and Crosby Street, near Prince Street, in SoHo, Manhattan, New York City. It was established in 1823 as "Columbia Garden" which in 1828 gained the name of the ''Sans Souci'' and was later the property ...

in 1890.

1890s

Greene wrote the book of the musical ''Peti, the Vagabond'', which starred Hubert Wilke in the title role and premiered at the California Theatre in San Francisco in 1890. He co-authored the 1892 play ''The New South'' with actor

Greene wrote the book of the musical ''Peti, the Vagabond'', which starred Hubert Wilke in the title role and premiered at the California Theatre in San Francisco in 1890. He co-authored the 1892 play ''The New South'' with actor Joseph R. Grismer

Joseph Rhode Grismer (November 4, 1849 – 1922) was an American stage actor, playwright, and theatrical director and producer. He was probably best remembered for his play ''The New South'' and for his revision of the Charlotte Blair Parker play ...

, about racial animus in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. The story followed a white United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

captain sent by the U.S. government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, executi ...

to arrest individuals illegally making and selling moonshine

Moonshine is alcohol proof, high-proof liquor, traditionally made or distributed alcohol law, illegally. The name was derived from a tradition of distilling the alcohol (drug), alcohol at night to avoid detection. In the first decades of the ...

. The captain's support of African Americans in that community puts him at odds with the white southerners, and his life is threatened. While the authors intended to critique racial prejudice, the work propagated racial stereotypes, and theatre scholars James Fisher and Felicia Hardison Londré described both it and a 1916 silent film adaptation of the play as "exploitive".

Greene collaborated with J. Cheever Goodwin on the book of the musical ''Africa'', which premiered in San Francisco in June 1893 prior to its Broadway run later that year at Star Theatre. He soon followed this with the libretto to a comic opera, ''The Maid of Plymouth'', based on the story of Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

historical figures Priscilla Alden

Priscilla Alden (, – ) was a noted member of Massachusetts's Plymouth Colony of Pilgrims and the wife of fellow colonist John Alden ( – 1687). They married in 1621 in Plymouth.

Biography

Priscilla was most likely born in Dorking in Surr ...

and Myles Standish

Myles Standish ( – October 3, 1656) was an English military officer and colonist. He was hired as military adviser for Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts, United States by the Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony), Pilgrims. Standish accompan ...

. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

's narrative poem ''The Courtship of Miles Standish

''The Courtship of Miles Standish'' is an 1858 narrative poem by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow about the early days of Plymouth Colony, the colonial settlement established in America by the ''Mayflower'' Pilgrims.

Overview

''Th ...

'' was an inspiration for the musical. The Bostonians

''The Bostonians'' is a novel by Henry James, first published as a serial in ''The Century Magazine'' in 1885–1886 and then as a book in 1886. This bittersweet tragicomedy centres on an odd triangle of characters: Basil Ransom, a political c ...

premiered the piece in Chicago in November 1893. It opened at the Broadway Theatre

Broadway theatre,Although ''theater'' is generally the spelling for this common noun in the United States (see American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, American and British English spelling differences), many of the List of ...

on January 15, 1894, starring Margaret Reid as Priscilla and Eugene Cowles as Myles.

With composer William Furst

William Wallace Furst (March 25, 1852 – July 11, 1917) was an American composer of musical theatre pieces and a music director, best remembered for supplying incidental music to theatrical productions on Broadway theatre, Broadway.

Biography

...

, Greene adapted Victor Roger's 1892 operetta ''Les 28 jours de Clairette'' (libretto by Hippolyte Raymond and Antony Mars

Antony Mars (22 October 1861 – 17 February 1915) was a French playwright

Biography

After he studied at a high school in Marseille, Antony March became a lawyer's clerk then an employee at the Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Est. En 1882, h ...

) Greene's version, titled ''The Little Trooper'' (or ''Little Miss Trooper''), was crafted as a starring vehicle for Della Fox

Della May Fox (October 13, 1870 – June 15, 1913) was an American singing comedian, whose popularity peaked in the 1890s when the diminutive Fox appeared opposite the very tall DeWolf Hopper in several musical theatre, musicals. She also toured s ...

. It opened at Broadway's Casino Theatre on August 30, 1894. Greene's 1894 play ''Under the Polar Star'' was a murder mystery investigating the death of the leader of an expedition in the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

. It was adapted by David Belasco

David Belasco (July 25, 1853 – May 14, 1931) was an American theatrical producer, impresario, director, and playwright. He was the first writer to adapt the short story ''Madame Butterfly'' for the stage. He launched the theatrical career of ...

for an 1896 production on Broadway at the Academy of Music.

Greene partnered with the playwright Ben Teal to craft the melodrama ''On Broadway'' (1896) starring Maggie Cline

Maggie Cline (January 1, 1857 – June 11, 1934) was an American vaudeville singer, active across the United States in the late nineteenth century, known as "The Irish Queen" and "The Bowery Brunhilde".

Biography

Cline was born in Haverhill, M ...

. The play had music by David Braham and featured Cline singing songs like John W. Kelly's "Throw Him Down, McCloskey". Greene wrote the book to Ludwig Englander's musical ''In Gay Paree'', which ran at the Casino Theatre in 1899.

1900s

Greene wrote the lyrics to the musical '' Aunt Hannah'', which premiered on Broadway at the Bijou Theatre in February 1900. This musical featured Greene's most successful song, "My Tiger Lily" (or "Ma Tiger Lily"). A month later, a second Broadway musical with a book by Greene, ''The Regatta Girl'', was staged at Koster & Bial's Music Hall. When Broadway producer John C. Fisher decided to bring the 1901 English musical ''The Silver Slipper'' to the United States for the first time, he had Greene Americanize the musical's original book by

Greene wrote the lyrics to the musical '' Aunt Hannah'', which premiered on Broadway at the Bijou Theatre in February 1900. This musical featured Greene's most successful song, "My Tiger Lily" (or "Ma Tiger Lily"). A month later, a second Broadway musical with a book by Greene, ''The Regatta Girl'', was staged at Koster & Bial's Music Hall. When Broadway producer John C. Fisher decided to bring the 1901 English musical ''The Silver Slipper'' to the United States for the first time, he had Greene Americanize the musical's original book by Owen Hall

Owen Hall (10 April 1853 – 9 April 1907) was the principal pen name of the Irish-born theatre writer, racing correspondent, theatre critic and solicitor, James Davis, when writing for the stage. After his successive careers in law and jour ...

. Other plays he was known for included ''Forgiven'' (1886) and ''A Man from the West'' (1900).

For the Golden Jubilee celebration of the founding of Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University is a private university, private Jesuit university in Santa Clara, California, United States. Established in 1851, Santa Clara University is the oldest operating institution of higher learning in California. The university' ...

(SCU), Greene penned a Passion Play

The Passion Play or Easter pageant is a dramatic Play (theatre), presentation depicting the Passion of Jesus: his Sanhedrin Trial of Jesus, trial, suffering and death. The viewing of and participation in Passion Plays is a traditional part of L ...

staged at the university in 1901, titled ''Nazareth''. Greene modeled it after the Oberammergau Passion Play

The Oberammergau Passion Play () is a passion play that has been performed every 10 years from 1634 to 1674 and each decadal year since 1680 (with a few exceptions) by the inhabitants of the village of Oberammergau, Bavaria, Germany. It was wr ...

. It was subsequently repeated at SCU every three years. It was also staged by The Lambs in 1902. SCU later awarded Greene an honorary doctorate.

The Lambs

Greene was a prominent member ofThe Lambs

The Lambs, Inc. (also known as The Lambs Club) is a New York City social club that nurtures those active in the arts, as well as those who are supporters of the arts, by providing activities and a clubhouse for its members. It is America's old ...

, a New York City social club that nurtures those active in the arts. Greene served as the president of The Lambs (called "The Shepherd") from 1891 to 1898, and again from 1902 to 1906. With Augustus Thomas

Augustus Thomas (January 8, 1857 – August 12, 1934) was an American playwright.

Biography

Born in St. Louis, Missouri and son of a medical doctor, Thomas worked a number of jobs including as a page in the 41st Congress, studying law, and gaini ...

serving as his boy (The Lamb's term for vice-president), Greene played an important role in The Lambs history. Together, Greene and Thomas successfully led the organization out of financial troubles, with Greene notably using his own money to prevent the club from defaulting on its bills and closing by personally paying off the club's debts with his own money in 1894. Greene and Thomas also acquired the organization's first permanent building, initiated The Lambs annual "gambols" (a public variety show), and almost doubled the size of the organization's membership.

Greene was also responsible for re-instituting The Lamb's "annual wash", an elaborate costumed event with a different theme each year. Beginning in 1895, he personally hosted the annual event at Los Olmos, his estate in Bayside, Queens. He also utilized his gift as a writer for The Lambs, penning more than 100 dramatic and comedic sketches for various entertainments and events put on by the club during his time with the organization. Fellow Lamb member and impressionist painter Robert Reid, painted a portrait of Greene which hangs in the Lambs club. In 1933, the year of his death, Greene was the first person to be awarded the title "Immortal Lamb" in the history of the club. The title is given only to a Lamb whose contributions led to the survival of the institution.

Later writing and film career in California

Greene returned to California after the death of his first wife, Alice Randolph Greene (née Wheeler), in 1910, and his subsequent marriage six months later to his second wife, the playwright Laura H. Robinson, in 1911. Greene had previously collaborated on several plays with Robinson and was 60 years old when he remarried. Financial problems prompted Greene to sell his

Greene returned to California after the death of his first wife, Alice Randolph Greene (née Wheeler), in 1910, and his subsequent marriage six months later to his second wife, the playwright Laura H. Robinson, in 1911. Greene had previously collaborated on several plays with Robinson and was 60 years old when he remarried. Financial problems prompted Greene to sell his Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

estate. He returned to San Francisco following its sale.

In his later career, Greene's writing shifted towards writing for vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

, and he produced a large number of dramatic sketches for the medium in the 1910s and 1920s. He also became a screenwriter for silent film

A silent film is a film without synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, w ...

s for the Lubin Manufacturing Company

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was an American motion picture production company that produced silent films from 1896 to 1916. Lubin films were distributed with a Liberty Bell trademark.

*

*

History

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was forme ...

from 1913 to 1916, also occasionally acting in and directing their films.

Upon his return to San Francisco, Greene resumed an active membership in San Francisco's Bohemian Club

The Bohemian Club is a private club with two locations: a city clubhouse in the Nob Hill district of San Francisco, California, and the Bohemian Grove, a retreat north of the city in Sonoma County. Founded in 1872 from a regular meeting of jour ...

(BC). His membership with the club extended back to the 1870s, and he maintained a connection to the organization during his years in New York City, attending and writing on the club's summer High Jinx entertainments at Bohemian Grove

The Bohemian Grove is a restricted 2,700-acre (1,100-hectare) campground in Monte Rio, California. Founded in 1878, it belongs to a private gentlemen's club known as the Bohemian Club. In mid-July each year, the Bohemian Grove hosts a more than ...

. He was a featured performer in the High Jinx entertainments in the summers of 1881 and 1886. He also frequently worked as playwright for the organizations entertainments, penning most of the "Christmas Low Jinx" entertainments performed by the club in the 1890s. He wrote the poem "False Gods" for the High Jinx of 1891. With composer Genaro Saldierna he wrote a musical parody of fellow BC member Joseph Redding's ''The Land of Happiness'' in 1917 that was entitled ''The Land of Flabbiness''. He also penned one of the Grove musical plays, writing the 1921 musical ''John of Nepomuk: Patron Saint of Bohemia'' in collaboration with composer Humphrey J. Stewart.

Greene befriended fellow Bohemian Club member Adolph B. Spreckels

Adolph Bernard Spreckels (January 5, 1857 – June 28, 1924) was a California businessman who ran the Spreckels Sugar Company and who donated the California Palace of the Legion of Honor art museum to the city of San Francisco in 1924. His wife, ...

of the Spreckels Sugar Company

The Spreckels Sugar Company is an American sugar beet refiner that for many years was the largest beet sugar producer in the western United States. The company was incorporated and originally headquartered in San Francisco, with its largest operati ...

. Spreckles and his wife, Alma de Bretteville Spreckels

Alma de Bretteville Spreckels (March 24, 1881 – August 7, 1968) was a wealthy socialite and philanthropist in San Francisco, California. She was known both as "Big Alma" (she was tall) and "The Great Grandmother of San Francisco". Among her ma ...

, used their philanthropy to build the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

art museum in San Francisco. Greene was so moved by the ground breaking ceremony of the museum in 1921 that he composed a poem, "The Groundbreaking", dedicated to the couple.

Greene also worked as a theatre critic for the ''San Francisco Journal''.

Later life and death

While visiting Los Angeles, Greene suffered from a

While visiting Los Angeles, Greene suffered from a vitreous hemorrhage

Vitreous hemorrhage is the extravasation, or leakage, of blood into the areas in and around the vitreous humor of the eye. The vitreous humor is the clear gel that fills the space between the lens and the retina of the eye. A variety of condition ...

in 1918 that caused him to lose sight suddenly in one of his eyes. He remained active in public life in San Francisco into his 80s. His last public appearance was at a performance of his Passion Play at Santa Clara University in the spring of 1933. In May 1933 he broke his hip and was unable to walk for the remainder of his life.

Clay M. Greene died on September 5, 1933, in San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. His daughter from his first marriage, the actress Helen Greene (1896-1947), and his second wife were with him at the time of his death.

Selected works

Books

*''The Dispensation And Other Plays'' (1914) *''Venetia, Avenger of the Lusitania'' (1919) * ''Verses of Love, Sentiment and Friendship'' (1921) *''In Memoriam: A Pageant of Friendship'' (1923)Filmography

Actor

*''Getting Atmosphere'' (1912, as The Gate Keeper; credited as C. E. Green) *''Her Educator'' (1912, as The Judge) *''A Humble Hero'' (1912, as The Prospector; credited as Daddy Green) *''A Motorcycle Adventure'' (1912, as John Martin) *'' The Other Fellow'' (1912, as Jim) *''Through Fire to Fortune'' (1914, as Henry Barrett) *''Treasures on Earth'' (1914, as Mark Dow)Director

*''The Belle of Barnegate'' (1915) *''Beyond All Is Love'' (1915) *''The Ogre and the Girl'' (1915) *''Americans After All'' (1916) *''Father's Night Off'' (1916) *''Her Wayward Sister'' (1916) *''Hubby Puts One Over'' (1916) *''Jenkins' Jinx'' (1916) *'' Love and Bullets'' (1916) *''Millionaire Billie'' (1916) *''Oh, You Uncle!'' (1916) *''Pickles and Diamonds'' (1916) *''Two Smiths and a Haff'' (1916) *''The Uplift'' (1916) *'' The Voice in the Night'' (1916) *''The Winning Number'' (1916)Screenwriter

*''The Fiancee and the Fairy'' (1913)

*''A Waif of the Desert'' (1913)

*''Forgiven; or, the Jack of Diamonds'' (1914)

* ''

*''The Fiancee and the Fairy'' (1913)

*''A Waif of the Desert'' (1913)

*''Forgiven; or, the Jack of Diamonds'' (1914)

* ''The Fortune Hunter

''The Fortune Hunter'' is a drama in three acts by W. S. Gilbert. The piece concerns an heiress who loses her fortune. Her shallow husband sues to annul the marriage, leaving her pregnant and taking up with a wealthy former lover. The piece wa ...

'' (1914)

*''The Girl at the Lock'' (1914)

*''The House Next Door'' (1914)

*''The Klondike Bubble'' (1914)

*''Little Breeches'' (1914)

*''Patsy at School'' (1914)

*''The Sleeping Sentinel

''The Sleeping Sentinel'' is a 1914 American black-and-white silent film that depicted President Abraham Lincoln pardoning a military sentry who had been sentenced to die for sleeping while on duty. The name of the film is taken from the Civil ...

'' (1914)

*''The Sorceress'' (1914)

*''A Strange Melody'' (1914)

*''Through Fire to Fortune, or, The Sunken Village'' (1914)

*''Treasures on Earth'' (1914)

*''The Trunk Mystery'' (1914)

*''The Belle of Barnegate'' (1915)

* '' The Climbers'' (1915)

*''The College Widow'' (1915)

*''The District Attorney'' (1915)

*'' The Great Ruby'' (1915)

*''It All Depends'' (1915)

*''The Ogre and the Girl'' (1915)

*''Patsy Among the Fairies'' (1915)

*''Patsy Among the Smugglers'' (1915)

*''Patsy at College'' (1915)

*''Patsy at the Seashore'' (1915)

*''Patsy's Elopement'' (1915)

*''Patsy's First Love'' (1915)

*''Patsy in a Seminary'' (1915)

*''Patsy in Business'' (1915)

*''Patsy in Town'' (1915)

*''Patsy, Married and Settled'' (1915)

*''Patsy on a Trolley Car'' (1915)

*''Patsy on a Yacht'' (1915)

*''Patsy's Vacation'' (1915)

*''A Siren of Corsica'' (1915)

*''The Sporting Duchess'' (1915)

*''Sweeter Than Revenge'' (1915)

*''A War Baby'' (1915)

*''The White Mask'' (1915)

*''Whom the Gods Would Destroy'' (1915)

*''The Witness'' (1915)

*''Billie's Double'' (1916)

*''Dare Devil Bill'' (1916)

*''The Evangelist'' (1916)

*''Millionaire Billie'' (1916)

*''Mr. Housekeeper'' (1916)

*''The New South'' (1916)

*''Two Smiths and a Haff'' (1916)

*''The Uplift'' (1916)

*''The Winning Number'' (1916)

*''A Wise Waiter'' (1916)

Films adapted from plays by Greene by other writers

* '' M'Liss'' (1918, adapted byFrances Marion

Frances Marion (born Marion Benson Owens; November 18, 1888 – May 12, 1973) was an American screenwriter, director, journalist and author often cited as one of the most renowned female screenwriters of the 20th century alongside June Mathis a ...

)

* ''Struck Oil'' (1919)

*'' Pawn Ticket 210'' (1922)

Stage works

Plays

*''Struck Oil

''Struck Oil'' is an 1874 play set during the American Civil War and a 1919 Australian silent film, now considered lost. The play, which introduced Maggie Moore to Australian theatre-goers, was popular with the Australian public and the basis o ...

'' (1874)

*''M'liss'' (1877, based on a story by Bret Harte

Bret Harte ( , born Francis Brett Hart, August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902) was an American short story writer and poet best remembered for short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush. In a caree ...

; co-authored with A. Slason Thompson)

*''Sharps and Flats'' (1880)

*''Chispa'' (1882, co-authored with A. Slason Thompson)

*''Louis Riel, or, The Northwest Rebellion'' (1886)

*''The Golden Giant'' (1886)

*''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1888, adapted from the novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

)

*''Carl's Folly'' (1891)

*''A High Roller'' (1891)

*''For Money'' (1891, co-written with Augustus Thomas

Augustus Thomas (January 8, 1857 – August 12, 1934) was an American playwright.

Biography

Born in St. Louis, Missouri and son of a medical doctor, Thomas worked a number of jobs including as a page in the 41st Congress, studying law, and gaini ...

)

*''The New South'' (1892)

*''Under the Polar Star'' (1894)

*''A Man from the West'' (1900)

*''The Gentle Mr Bellew of France'' (1902)

*''The Little Minister and His Mash, or A Very Hot Scotch'' (1902)

*''Over a Welsh Rarebit'' (1903)

*''For Love's Sweet Sake'' (1906)

Musicals and operas

*''Pico; or, The legend of Castle Molfi'', a fairypantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment, generally combining gender-crossing actors and topical humour with a story more or less based on a well-known fairy tale, fable or ...

(1883, later retitled ''Fantasma'')

*''Le Voyage en Suisse'' (1883, Greene crafted the revised libretto of this work)

*''Sybil'' (1886, libretto by Greene; music by John F. Mitchell)

*''Hans the Boatman'', musical (1887, book and lyrics by Greene, music by various composers)

*''Our Jennie'', musical (1887; music by Barney Fagan

Barney Fagan (January 12, 1850 – January 12, 1937) was an American performer, director, choreographer, and composer.

Career

Barney Fagan was born as Bernard J. Fagan in Boston, son of Douglass and Ellen Fagan. His father was the deputy w ...

; libretto by Greene)

*'' Blue Beard, Jr.'', a musical in four acts (1889, libretto by Greene; music by Fred J. Eustis, Richard Maddern, and John Joseph Braham Sr.)

*''Peti, the Vagabond'', musical (1890, libretto by Greene)

*''The Maid of Plymouth'', comic opera in two acts (1893, libretto by Greene; music by Thomas Pearsall Thorne)

*''Africa'', musical (1893; music by Randolph Cruger; libretto co-authored by Greene and J. Cheever Goodwin)

*''The Little Trooper'', operetta (1894, also known as ''Little Miss Trooper''; Greene wrote a new English language libretto to Victor Roger's 1892 operetta ''Les 28 jours de Clairette''; new music by William Furst

William Wallace Furst (March 25, 1852 – July 11, 1917) was an American composer of musical theatre pieces and a music director, best remembered for supplying incidental music to theatrical productions on Broadway theatre, Broadway.

Biography

...

)

*''On Broadway'', play with music (1896)

*''April Fool'', pasticcio

In music, a ''pasticcio'' or ''pastiche'' is an opera or other musical work composed of works by different composers who may or may not have been working together, or an adaptation or localization of an existing work that is loose, unauthorized, ...

(1897; libretto by Greene)

*''A Musical Discord'', pasticcio

In music, a ''pasticcio'' or ''pastiche'' is an opera or other musical work composed of works by different composers who may or may not have been working together, or an adaptation or localization of an existing work that is loose, unauthorized, ...

(1897; libretto by Greene)

*''In Gay Paree'', musical (1899, book by Greene; music by Ludwig Englander; lyrics by Grant Stewart)

*''Sharp Becky'', burlesque (1899, adapted into a portion of the burlesque musical ''Around New York in 80 Minutes'')

*''The Conspirators'', comic opera (1899, libretto by Greene; music by Humphrey John Stewart

Humphrey John Stewart (22 May 1856 – 1932) was an American composer and organist, born in England. A native of London, he came to the United States in 1886, and served for many years as a church organist on the West Coast. In 1898, he was award ...

),

*''The Remarkable Pipe Dream of Sherlock Holmes'' (1900, originally Lamb's Gambol; adapted into a portion of the burlesque musical ''Around New York in 80 Minutes'')

*'' Aunt Hannah'', musical (1900, lyrics by Greene; music by A. Baldwin Sloane

Alfred Baldwin Sloane, often given as A. Baldwin Sloane, (28 August 1872, Baltimore – 21 February 1925, Red Bank, New Jersey) was the most prolific songwriter for Broadway musical comedies in the United States at the beginning of the 20th centur ...

; book by Matthew J. Royal)

* ''The Regatta Girl'', musical (1900; libretto by Greene; music by Harry McLellan)

* ''The Silver Slipper'', musical (1902 revised libretto by Greene; music by Leslie Stuart)

* ''John of Nepomuk: Patron Saint of Bohemia'' (1921, book and lyrics by Greene; music by composer Humphrey J. Stewart)

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Greene, Clay M. 1850 births 1933 deaths American dramatists and playwrights American journalists American musical theatre librettists American musical theatre lyricists American silent film directors American male silent film actors Broadway composers and lyricists Santa Clara University alumni Songwriters from New York (state) Songwriters from California The Lambs presidents Members of The Lambs Club Writers from New York City Writers from San Francisco