Clause on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

These two embedded clauses are adjunct clauses because they provide circumstantial information that modifies a superordinate expression. The first is a dependent of the main verb of the matrix clause and the second is a dependent of the object noun. The arrow dependency edges identify them as adjuncts. The arrow points away from the adjunct towards it

These two embedded clauses are adjunct clauses because they provide circumstantial information that modifies a superordinate expression. The first is a dependent of the main verb of the matrix clause and the second is a dependent of the object noun. The arrow dependency edges identify them as adjuncts. The arrow points away from the adjunct towards it

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

, a clause is a constituent or phrase

In grammar, a phrasecalled expression in some contextsis a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English language, English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adject ...

that comprises a semantic predicand

In semantics, a predicand is an argument in an utterance, specifically that of which something is predicated. By extension, in syntax, it is the constituent in a clause typically functioning as the subject.

Examples

In the most typical cases ...

(expressed or not) and a semantic predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject and a syntactic predicate, the latter typically a verb phrase

In linguistics, a verb phrase (VP) is a syntax, syntactic unit composed of a verb and its argument (linguistics), arguments except the subject (grammar), subject of an independent clause or coordinate clause. Thus, in the sentence ''A fat man quic ...

composed of a verb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

with or without any object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an a ...

s and other modifiers

In linguistics, a modifier is an optional element in phrase structure or clause structure which ''modifies'' the meaning of another element in the structure. For instance, the adjective "red" acts as a modifier in the noun phrase "red ball", provi ...

. However, the subject is sometimes unexpressed if it is easily deducible from the context, especially in null-subject language

In linguistic typology, a null-subject language is a language whose grammar permits an independent clause to lack an explicit subject; such a clause is then said to have a null subject.

In the principles and parameters framework, the null s ...

s but also in other languages, including instances of the imperative mood

The imperative mood is a grammatical mood that forms a command or request.

The imperative mood is used to demand or require that an action be performed. It is usually found only in the present tense, second person. They are sometimes called ' ...

in English.

A complete simple sentence

In grammar, sentence and clause structure, commonly known as sentence composition, is the classification of sentences based on the number and kind of clauses in their syntactic structure. Such division is an element of traditional grammar.

Typo ...

contains a single clause with a finite verb

A finite verb is a verb that contextually complements a subject, which can be either explicit (like in the English indicative) or implicit (like in null subject languages or the English imperative). A finite transitive verb or a finite intra ...

. Complex sentence

In grammar, sentence and clause structure, commonly known as sentence composition, is the classification of sentences based on the number and kind of clauses in their syntactic structure. Such division is an element of traditional grammar.

Typolo ...

s contain at least one clause subordinated ( ''dependent'') to an ''independent clause

In traditional grammar, an independent clause (or main clause) is a clause that can stand by itself as a ''simple sentence''. An independent clause contains a subject and a predicate and makes sense by itself.

Independent clauses can be joined ...

'' (one that could stand alone as a simple sentence), which may be co-ordinated with other independents with or without dependents. Some dependent clauses are non-finite, i.e. they do not contain any element/verb marking a specific tense.

Matrix Clauses

A clause that contains one or more dependent or subordinate clauses is called a . A matrix clause can be the main clause or any subordinate clause that itself contains one or more (additional) subordinate clauses.Two major distinctions

A primary division for the discussion of clauses is the distinction between independent clauses and dependent clauses. An independent clause can stand alone, i.e. it can constitute a complete sentence by itself. A dependent clause, by contrast, relies on an independent clause's presence to be efficiently utilizable. A second significant distinction concerns the difference between finite and non-finite clauses. A finite clause contains a structurally centralfinite verb

A finite verb is a verb that contextually complements a subject, which can be either explicit (like in the English indicative) or implicit (like in null subject languages or the English imperative). A finite transitive verb or a finite intra ...

, whereas the structurally central word of a non-finite clause is often a non-finite verb

Non-finite verbs, are verb forms that do not show tense, person, or number. They include:

# Infinitives (e.g., to go, to see) - They often function as nouns or the base form of a verb

# Gerunds (e.g., going, seeing) - These act as nouns but are ...

. Traditional grammar focuses on finite clauses, the awareness of non-finite clauses having arisen much later in connection with the modern study of syntax. The discussion here also focuses on finite clauses, although some aspects of non-finite clauses are considered further below.

Clauses can be classified according to a distinctive trait that is a prominent characteristic of their syntactic form. The position of the finite verb is one major trait used for classification, and the appearance of a specific type of focusing word (e.g. 'Wh'-word) is another. These two criteria overlap to an extent, which means that often no single aspect of syntactic form is always decisive in deciding how the clause functions. There are, however, strong tendencies.

Standard SV-clauses

Standard SV-clauses (subject-verb) are the norm in English. They are usually declarative (as opposed to exclamative, imperative, or interrogative); they express information neutrally, e.g. ::The pig has not yet been fed. Declarative clause, standard SV order ::I've been hungry for two hours. Declarative clause, standard SV order ::...that I've been hungry for two hours. Declarative clause, standard SV order, but functioning as a subordinate clause due to the appearance of the subordinator ''that'' Declarative clauses like these are by far the most frequently occurring type of clause in any language. They can be viewed as basic, with other clause types being derived from them. Standard SV-clauses can also be interrogative or exclamative, however, given the appropriate intonation contour and/or the appearance of a question word, e.g. ::a. The pig has not yet been fed? Rising intonation on ''fed'' makes the clause a yes/no question. ::b. The pig has not yet been fed! Spoken forcefully, this clause is exclamative. ::c. You've been hungry for how long? Appearance of interrogative word ''how'' and rising intonation make the clause a constituent question Examples like these demonstrate that how a clause functions cannot be known based entirely on a single distinctive syntactic criterion. SV-clauses are usually declarative, but intonation and/or the appearance of a question word can render them interrogative or exclamative.Verb first clauses

Verb first clauses in English usually play one of three roles: 1. They express a yes/no-question viasubject–auxiliary inversion

Subject–auxiliary inversion (SAI; also called subject–operator inversion) is a frequently occurring type of inversion (linguistics), inversion in the English language whereby a finite auxiliary verb – taken here to include finite forms of th ...

, 2. they express a condition as an embedded clause, or 3. they express a command via imperative mood, e.g.

::a. He must stop laughing. Standard declarative SV-clause (verb second order)

::b. Should he stop laughing? Yes/no-question expressed by verb first order

::c. Had he stopped laughing, ... Condition expressed by verb first order

::d. Stop laughing! Imperative formed with verb first order

::a. They have done the job. Standard declarative SV-clause (verb second order)

::b. Have they done the job? Yes/no-question expressed by verb first order

::c. Had they done the job, ... Condition expressed by verb first order

::d. Do the job! Imperative formed with verb first order

Most verb first clauses are independent clauses. Verb first conditional clauses, however, must be classified as embedded clauses because they cannot stand alone.

''Wh''-clauses

In English, ''Wh''-clauses contain a ''wh''-word. ''Wh''-words often serve to help express a constituent question. They are also prevalent, though, as relative pronouns, in which case they serve to introduce a relative clause and are not part of a question. The ''wh''-word focuses a particular constituent, and most of the time, it appears in clause-initial position. The following examples illustrate standard interrogative ''wh''-clauses. The b-sentences are direct questions (independent clauses), and the c-sentences contain the corresponding indirect questions (embedded clauses): ::a. Sam likes the meat. Standard declarative SV-clause ::b. Who likes the meat? Matrix interrogative ''wh''-clause focusing on the subject ::c. They asked who likes the meat. Embedded interrogative ''wh''-clause focusing on the subject ::a. Larry sent Susan to the store. Standard declarative SV-clause ::b. Whom did Larry send to the store? Matrix interrogative ''wh''-clause focusing on the object, subject-auxiliary inversion present ::c. We know whom Larry sent to the store. Embedded ''wh''-clause focusing on the object, subject-auxiliary inversion absent ::a. Larry sent Susan to the store. Standard declarative SV-clause ::b. Where did Larry send Susan? Matrix interrogative ''wh''-clause focusing on the oblique object, subject-auxiliary inversion present ::c. Someone is wondering where Larry sent Susan. Embedded ''wh''-clause focusing on the oblique object, subject-auxiliary inversion absent One important aspect of matrix ''wh''-clauses is that subject-auxiliary inversion is obligatory when something other than the subject is focused. When it is the subject (or something embedded in the subject) that is focused, however, subject-auxiliary inversion does not occur. ::a. Who called you? Subject focused, no subject-auxiliary inversion ::b. Whom did you call? Object focused, subject-auxiliary inversion occurs Another important aspect of ''wh''-clauses concerns the absence of subject-auxiliary inversion in embedded clauses, as illustrated in the c-examples just produced. Subject-auxiliary inversion is obligatory in matrix clauses when something other than the subject is focused, but it never occurs in embedded clauses regardless of the constituent that is focused. A systematic distinction in word order emerges across matrix ''wh''-clauses, which can have VS order, and embedded ''wh''-clauses, which always maintain SV order, e.g. ::a. Why are they doing that? Subject-auxiliary inversion results in VS order in matrix ''wh''-clause. ::b. They told us why they are doing that. Subject-auxiliary inversion is absent in embedded ''wh''-clause. ::c. *They told us why are they doing that. Subject-auxiliary inversion is blocked in embedded ''wh''-clause. ::a. Whom is he trying to avoid? Subject-auxiliary inversion results in VS order in matrix ''wh''-clause. ::b. We know whom he is trying to avoid. Subject-auxiliary inversion is absent in embedded ''wh-''clause. ::c. *We know whom is he trying to avoid. Subject-auxiliary inversion is blocked in embedded ''wh''-clause.Relative clauses

Relative clause

A relative clause is a clause that modifies a noun or noun phrase and uses some grammatical device to indicate that one of the arguments in the relative clause refers to the noun or noun phrase. For example, in the sentence ''I met a man who wasn ...

s are a mixed group. In English they can be standard SV-clauses if they are introduced by ''that'' or lack a relative pronoun entirely, or they can be ''wh''-clauses if they are introduced by a ''wh''-word that serves as a relative pronoun

A relative pronoun is a pronoun that marks a relative clause. An example is the word ''which'' in the sentence "This is the house which Jack built." Here the relative pronoun ''which'' introduces the relative clause. The relative clause modifies th ...

.

Clauses according to semantic predicate-argument function

Embedded clauses can be categorized according to their syntactic function in terms of predicate-argument structures. They can function asargument

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persu ...

s, as adjuncts, or as predicative expression

A predicative expression (or just predicative) is part of a clause predicate, and is an expression that typically follows a copula or linking verb, e.g. ''be'', ''seem'', ''appear'', or that appears as a second complement (object complement) of ...

s. That is, embedded clauses can be an argument of a predicate, an adjunct on a predicate, or (part of) the predicate itself. The predicate in question is usually the predicate of an independent clause, but embedding of predicates is also frequent.

Argument clauses

A clause that functions as the argument of a given predicate is known as an ''argument clause''. Argument clauses can appear as subjects, as objects, and as obliques. They can also modify a noun predicate, in which case they are known as '' content clauses''. ::That they actually helped was really appreciated. SV-clause functioning as the subject argument ::They mentioned that they had actually helped. SV-clause functioning as the object argument ::What he said was ridiculous. ''Wh''-clause functioning as the subject argument ::We know what he said. ''Wh''-clause functioning as an object argument ::He talked about what he had said. ''Wh''-clause functioning as an oblique object argument The following examples illustrate argument clauses that provide the content of a noun. Such argument clauses are content clauses: ::a. the claim that he was going to change it Argument clause that provides the content of a noun (i.e. content clause) ::b. the claim that he expressed Adjunct clause (relative clause) that modifies a noun ::a. the idea that we should alter the law Argument clause that provides the content of a noun (i.e. content clause) ::b. the idea that came up Adjunct clause (relative clause) that modifies a noun The content clauses like these in the a-sentences are arguments. Relative clauses introduced by the relative pronoun ''that'' as in the b-clauses here have an outward appearance that is closely similar to that of content clauses. The relative clauses are adjuncts, however, not arguments.Adjunct clauses

Adjunct clauses are embedded clauses that modify an entire predicate-argument structure. All clause types (SV-, verb first, ''wh-'') can function as adjuncts, although the stereotypical adjunct clause is SV and introduced by a subordinator (i.e. subordinate conjunction, e.g. ''after'', ''because'', ''before'', ''now'', etc.), e.g. ::a. Fred arrived before you did. Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause ::b. After Fred arrived, the party started. Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause ::c. Susan skipped the meal because she is fasting. Adjunct clause modifying matrix clause These adjunct clauses modify the entire matrix clause. Thus ''before you did'' in the first example modifies the matrix clause ''Fred arrived''. Adjunct clauses can also modify a nominal predicate. The typical instance of this type of adjunct is a relative clause, e.g. ::a. We like the music that you brought. Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun ''music'' ::b. The people who brought music were singing loudly. Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun ''people'' ::c. They are waiting for some food that will not come. Relative clause functioning as an adjunct that modifies the noun ''food''Predicative clauses

An embedded clause can also function as apredicative expression

A predicative expression (or just predicative) is part of a clause predicate, and is an expression that typically follows a copula or linking verb, e.g. ''be'', ''seem'', ''appear'', or that appears as a second complement (object complement) of ...

. That is, it can form (part of) the predicate of a greater clause.

::a. That was when they laughed. Predicative SV-clause, i.e. a clause that functions as (part of) the main predicate

::b. He became what he always wanted to be. Predicative ''wh''-clause, i.e. ''wh''-clause that functions as (part of) the main predicate

These predicative clauses are functioning just like other predicative expressions, e.g. predicative adjectives (''That was good'') and predicative nominals (''That was the truth''). They form the matrix predicate together with the copula.

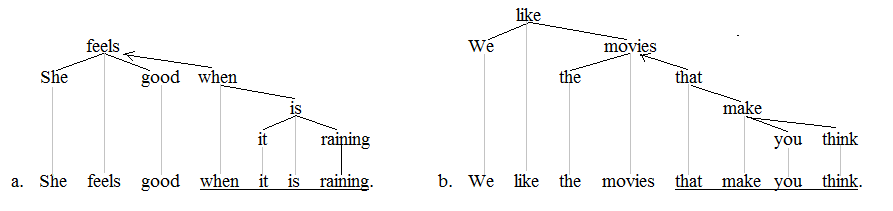

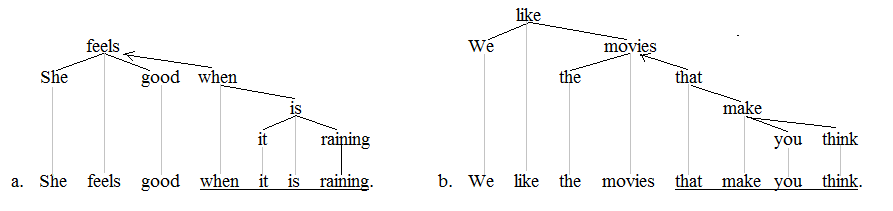

Representing clauses

Some of the distinctions presented above are represented in syntax trees. These trees make the difference between main and subordinate clauses very clear, and they also illustrate well the difference between argument and adjunct clauses. The followingdependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern Grammar, grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of Phrase structure grammar, phrase structure) and that can be traced back prima ...

trees show that embedded clauses are dependent on an element in the independent clause, often on a verb:

::

The independent clause comprises the entire trees in both instances, whereas the embedded clauses constitute arguments of the respective independent clauses: the embedded ''wh''-clause ''what we want'' is the object argument of the predicate ''know''; the embedded clause ''that he is gaining'' is the subject argument of the predicate ''is motivating''. Both of these argument clauses are dependent on the verb of the matrix clause. The following trees identify adjunct clauses using an arrow dependency edge:

:: These two embedded clauses are adjunct clauses because they provide circumstantial information that modifies a superordinate expression. The first is a dependent of the main verb of the matrix clause and the second is a dependent of the object noun. The arrow dependency edges identify them as adjuncts. The arrow points away from the adjunct towards it

These two embedded clauses are adjunct clauses because they provide circumstantial information that modifies a superordinate expression. The first is a dependent of the main verb of the matrix clause and the second is a dependent of the object noun. The arrow dependency edges identify them as adjuncts. The arrow points away from the adjunct towards it governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

to indicate that semantic selection

Selection may refer to:

Science

* Selection (biology), also called natural selection, selection in evolution

** Sex selection, in genetics

** Mate selection, in mating

** Sexual selection in humans, in human sexuality

** Human mating strat ...

is running counter to the direction of the syntactic dependency; the adjunct is selecting its governor. The next four trees illustrate the distinction mentioned above between matrix ''wh''-clauses and embedded ''wh''-clauses

::

The embedded ''wh''-clause is an object argument each time. The position of the ''wh''-word across the matrix clauses (a-trees) and the embedded clauses (b-trees) captures the difference in word order. Matrix ''wh''-clauses have V2 word order

In syntax, verb-second (V2) word order is a sentence structure in which the finite verb of a sentence or a clause is placed in the clause's second position, so that the verb is preceded by a single word or group of words (a single constituent). ...

, whereas embedded wh-clauses have (what amounts to) V3 word order. In the matrix clauses, the ''wh''-word is a dependent of the finite verb, whereas it is the head over the finite verb in the embedded ''wh''-clauses.

Clauses vs phrases

There has been confusion about the distinction between clauses andphrase

In grammar, a phrasecalled expression in some contextsis a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English language, English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adject ...

s. This confusion is due in part to how these concepts are employed in the phrase structure grammar

The term phrase structure grammar was originally introduced by Noam Chomsky as the term for grammar studied previously by Emil Post and Axel Thue ( Post canonical systems). Some authors, however, reserve the term for more restricted grammars in t ...

s of the Chomskyan tradition. In the 1970s, Chomskyan grammars began labeling many clauses as CPs (i.e. complementizer phrases) or as IPs (i.e. inflection phrases), and then later as TPs (i.e. tense phrases), etc. The choice of labels was influenced by the theory-internal desire to use the labels consistently. The X-bar schema acknowledged at least three projection levels for every lexical head: a minimal projection (e.g. N, V, P, etc.), an intermediate projection (e.g. N', V', P', etc.), and a phrase level projection (e.g. NP, VP, PP, etc.). Extending this convention to the clausal categories occurred in the interest of the consistent use of labels.

This use of labels should not, however, be confused with the actual status of the syntactic units to which the labels are attached. A more traditional understanding of clauses and phrases maintains that phrases are not clauses, and clauses are not phrases. There is a progression in the size and status of syntactic units: ''words < phrases < clauses''. The characteristic trait of clauses, i.e. the presence of a subject and a (finite) verb, is absent from phrases. Clauses can be, however, embedded inside phrases.

Non-finite clauses

The central word of a non-finite clause is usually anon-finite verb

Non-finite verbs, are verb forms that do not show tense, person, or number. They include:

# Infinitives (e.g., to go, to see) - They often function as nouns or the base form of a verb

# Gerunds (e.g., going, seeing) - These act as nouns but are ...

(as opposed to a finite verb

A finite verb is a verb that contextually complements a subject, which can be either explicit (like in the English indicative) or implicit (like in null subject languages or the English imperative). A finite transitive verb or a finite intra ...

). There are various types of non-finite clauses that can be acknowledged based in part on the type of non-finite verb at hand. Gerund

In linguistics, a gerund ( abbreviated ger) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages; most often, but not exclusively, it is one that functions as a noun. The name is derived from Late Latin ''gerundium,'' meaning "which is ...

s are widely acknowledged to constitute non-finite clauses, and some modern grammars also judge many ''to''-infinitives to be the structural locus of non-finite clauses. Finally, some modern grammars also acknowledge so-called small clauses, which often lack a verb altogether. It should be apparent that non-finite clauses are (by and large) embedded clauses.

Gerund clauses

The underlined words in the following examples are considered non-finite clauses, e.g. ::a. Bill stopping the project was a big disappointment. Non-finite gerund clause ::b. Bill's stopping of the project was a big disappointment. Gerund with noun status ::a. We've heard about Susan attempting a solution. Non-finite gerund clause ::b. We've heard about Susan's attempting of a solution. Gerund with noun status ::a. They mentioned him cheating on the test. Non-finite gerund clause ::b. They mentioned his cheating on the test. Gerund with noun status Each of the gerunds in the a-sentences (''stopping'', ''attempting'', and ''cheating'') constitutes a non-finite clause. The subject-predicate relationship that has long been taken as the defining trait of clauses is fully present in the a-sentences. The fact that the b-sentences are also acceptable illustrates the enigmatic behavior of gerunds. They seem to straddle two syntactic categories: they can function as non-finite verbs or as nouns. When they function as nouns as in the b-sentences, it is debatable whether they constitute clauses, since nouns are not generally taken to be constitutive of clauses.''to''-infinitive clauses

Some modern theories of syntax take many ''to''-infinitives to be constitutive of non-finite clauses. This stance is supported by the clear predicate status of many ''to''-infinitives. It is challenged, however, by the fact that ''to''-infinitives do not take an overt subject, e.g. ::a. She refuses to consider the issue. ::a. He attempted to explain his concerns. The ''to''-infinitives ''to consider'' and ''to explain'' clearly qualify as predicates (because they can be negated). They do not, however, take overt subjects. The subjects ''she'' and ''he'' are dependents of the matrix verbs ''refuses'' and ''attempted'', respectively, not of the ''to''-infinitives. Data like these are often addressed in terms of control. The matrix predicates ''refuses'' and ''attempted'' are control verbs; they control the embedded predicates ''consider'' and ''explain'', which means they determine which of their arguments serves as the subject argument of the embedded predicate. Some theories of syntax posit the null subjectPRO

Pro is an abbreviation meaning "professional".

Pro, PRO or variants thereof might also refer to:

People

* Miguel Pro (1891–1927), Mexican priest

* Pro Hart (1928–2006), Australian painter

* Mlungisi Mdluli (born 1980), South African ret ...

(i.e. pronoun) to help address the facts of control constructions, e.g.

::b. She refuses PRO to consider the issue.

::b. He attempted PRO to explain his concerns.

With the presence of PRO as a null subject, ''to''-infinitives can be construed as complete clauses, since both subject and predicate are present.

PRO-theory is particular to one tradition in the study of syntax and grammar (Government and Binding Theory Government and binding (GB, GBT) is a theory of syntax and a phrase structure grammar in the tradition of transformational grammar developed principally by Noam Chomsky in the 1980s. This theory is a radical revision of his earlier theories and was ...

, Minimalist Program

In linguistics, the minimalist program is a major line of inquiry that has been developing inside generative grammar since the early 1990s, starting with a 1993 paper by Noam Chomsky.

Following Imre Lakatos's distinction, Chomsky presents minima ...

). Other theories of syntax and grammar (e.g. Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar

Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG) is a highly lexicalized, constraint-based grammar

developed by Carl Pollard and Ivan Sag. It is a type of phrase structure grammar, as opposed to a dependency grammar, and it is the immediate successor t ...

, Construction Grammar

Construction grammar (often abbreviated CxG) is a family of theories within the field of cognitive linguistics which posit that constructions, or learned pairings of linguistic patterns with meanings, are the fundamental building blocks of human ...

, dependency grammar

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern Grammar, grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation (as opposed to the ''constituency relation'' of Phrase structure grammar, phrase structure) and that can be traced back prima ...

) reject the presence of null elements such as PRO, which means they are likely to reject the stance that ''to''-infinitives constitute clauses.

Small clauses

Another type of construction that some schools of syntax and grammar view as non-finite clauses is the so-called small clause. A typical small clause consists of a noun phrase and a predicative expression,For the basic characteristics of small clauses, see Crystal (1997:62). e.g. ::We consider that a joke. Small clause with the predicative noun phrase ''a joke'' ::Something made him angry. Small clause with the predicative adjective ''angry'' ::She wants us to stay. Small clause with the predicative non-finite ''to''-infinitive ''to stay'' The subject-predicate relationship is clearly present in the underlined strings. The expression on the right is a predication over the noun phrase immediately to its left. While the subject-predicate relationship is indisputably present, the underlined strings do not behave as single constituents, a fact that undermines their status as clauses. Hence one can debate whether the underlined strings in these examples should qualify as clauses. The layered structures of the chomskyan tradition are again likely to view the underlined strings as clauses, whereas the schools of syntax that posit flatter structures are likely to reject clause status for them.See also

*Adverbial clause

An adverbial clause is a dependent clause that functions as an adverb. That is, the entire clause modifies a separate element within a sentence or the sentence itself. As with all clauses, it contains a subject and predicate, though the subject a ...

*Balancing and deranking In linguistics, balancing and deranking are terms used to describe the form of verbs used in various types of subordinate clauses and also sometimes in co-ordinate constructions.

* A verb form is said to be balanced if it is identical to forms use ...

*Dependent clause

A dependent clause, also known as a subordinate clause, subclause or embedded clause, is a certain type of clause that juxtaposes an independent clause within a complex sentence. For instance, in the sentence "I know Bette is a dolphin", the claus ...

*Phrase

In grammar, a phrasecalled expression in some contextsis a group of words or singular word acting as a grammatical unit. For instance, the English language, English expression "the very happy squirrel" is a noun phrase which contains the adject ...

*Relative clause

A relative clause is a clause that modifies a noun or noun phrase and uses some grammatical device to indicate that one of the arguments in the relative clause refers to the noun or noun phrase. For example, in the sentence ''I met a man who wasn ...

*Sentence (linguistics)

In linguistics and grammar, a sentence is a Expression (linguistics), linguistic expression, such as the English example "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog." In traditional grammar, it is typically defined as a string of words that expre ...

* T-unit

* Thematic equative

Notes

References

* * * Kroeger, Paul R. (2005). ''Analysing Grammar: An Introduction''. Cambridge. UK:Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

.

* {{cite journal , author1=Timothy Osborne , author2=Thomas Gross , year=2012 , title=Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar , journal=Cognitive Linguistics , volume=23 , number=1 , pages=163–214 , doi=10.1515/cog-2012-0006

* Radford, Andrew (2004). ''English syntax: An introduction''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Syntactic entities

Clauses

Syntactic categories