Classical-liberal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics;

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, the Reform Act of 1832 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League brought together a coalition of liberal and radical groups in support of free trade under the leadership of Richard Cobden and John Bright, who opposed aristocratic privilege, militarism, and public expenditure and believed that the backbone of Great Britain was the yeoman farmer. Their policies of low public expenditure and low taxation were adopted by

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, the Reform Act of 1832 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League brought together a coalition of liberal and radical groups in support of free trade under the leadership of Richard Cobden and John Bright, who opposed aristocratic privilege, militarism, and public expenditure and believed that the backbone of Great Britain was the yeoman farmer. Their policies of low public expenditure and low taxation were adopted by

Central to classical liberal ideology was their interpretation of

Central to classical liberal ideology was their interpretation of

''Fifty Years of American Idealism: 1865–1915''

short history of '' The Nation'' plus numerous excerpts, most by

civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

under the rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannica ...

with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, economic freedom, political freedom

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and F ...

and freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

. It gained full flowering in the early 18th century, building on ideas stemming at least as far back as the 13th century within the Iberian, Anglo-Saxon, and central European contexts and was foundational to the American Revolution and "American Project" more broadly.

Notable liberal individuals whose ideas contributed to classical liberalism include John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

,Steven M. Dworetz (1994). ''The Unvarnished Doctrine: Locke, Liberalism, and the American Revolution''. Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of ...

, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo. It drew on classical economics

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith ...

, especially the economic ideas as espoused by Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

in Book One of '' The Wealth of Nations'' and on a belief in natural law, progress, and utilitarianism. In contemporary times, Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises, Thomas Sowell, George Stigler and Larry Arnhart are seen as the most prominent advocates of classical liberalism.

Classical liberalism, contrary to liberal branches like social liberalism, looks more negatively on social policies, taxation and the state involvement in the lives of individuals, and it advocates deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

. Until the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and the rise of social liberalism, it was used under the name of economic liberalism. As a term, ''classical liberalism'' was applied in retronym to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from social liberalism. By modern standards, in the United States, simple ''liberalism'' often means social liberalism, but in Europe and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, simple ''liberalism'' often means classical liberalism.

In the United States, ''classical liberalism'' may be described as "fiscally conservative" and "socially liberal". Despite this context, classical liberalism rejects conservatism's higher tolerance for protectionism and social liberalism's inclination for collective group rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group '' qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by individual people; even if they are group-differentiated, which ...

, due to classical liberalism's central principle of individualism. Classical liberalism is also considered closely tied with right-libertarianism in the United States. In Europe, ''liberalism'', whether social (especially radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

) or conservative, is classical liberalism in itself, so the term ''classical liberalism'' mainly refers to centre-right economic liberalism.

Evolution of core beliefs

Core beliefs of classical liberals included new ideaswhich departed from both the older conservative idea of society as a family and from the later sociological concept of society as a complex set of social networks. Classical liberals believed that individuals are "egoistic, coldly calculating, essentially inert and atomistic" and that society is no more than the sum of its individual members. Classical liberals agreed with Thomas Hobbes that government had been created by individuals to protect themselves from each other and that the purpose of government should be to minimize conflict between individuals that would otherwise arise in astate of nature

The state of nature, in moral and political philosophy, religion, social contract theories and international law, is the hypothetical life of people before societies came into existence. Philosophers of the state of nature theory deduce that ther ...

. These beliefs were complemented by a belief that labourers could be best motivated by financial incentive. This belief led to the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which limited the provision of social assistance, based on the idea that markets

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

* Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

* Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, a ...

are the mechanism that most efficiently leads to wealth. Adopting Thomas Robert Malthus's population theory, they saw poor urban conditions as inevitable, believed population growth would outstrip food production and thus regarded that consequence desirable because starvation would help limit population growth. They opposed any income or wealth redistribution, believing it would be dissipated by the lowest orders.

Drawing on ideas of Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

, classical liberals believed that it is in the common interest that all individuals be able to secure their own economic self-interest. They were critical of what would come to be the idea of the welfare state as interfering in a free market.Alan Ryan, "Liberalism", in ''A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy'', ed. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1995), p. 293. Despite Smith's resolute recognition of the importance and value of labour and of labourers, classical liberals criticized labour's group rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group '' qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by individual people; even if they are group-differentiated, which ...

being pursued at the expense of individual rights while accepting corporations' rights, which led to inequality of bargaining power. Classical liberals argued that individuals should be free to obtain work from the highest-paying employers, while the profit motive

In economics, the profit motive is the motivation of firms that operate so as to maximize their profits. Mainstream microeconomic theory posits that the ultimate goal of a business is "to make money" - not in the sense of increasing the firm's s ...

would ensure that products that people desired were produced at prices they would pay. In a free market, both labour and capital would receive the greatest possible reward, while production would be organized efficiently to meet consumer demand. Classical liberals argued for what they called a minimal state, limited to the following functions:

* A government to protect individual rights and to provide services that cannot be provided in a free market.

* A common national defence to provide protection against foreign invaders.

* Laws to provide protection for citizens from wrongs committed against them by other citizens, which included protection of private property, enforcement of contracts and common law.

* Building and maintaining public institutions.

* Public works that included a stable currency, standard weights and measures and building and upkeep of roads, canals, harbours, railways, communications and postal services.

Classical liberals asserted that rights are of a negative nature and therefore stipulate that other individuals and governments are to refrain from interfering with the free market, opposing social liberals who assert that individuals have positive rights, such as the right to vote, the right to an education, the right to health care, and the right to a living wage. For society to guarantee positive rights, it requires taxation over and above the minimum needed to enforce negative rights. Kelly, D. (1998): ''A Life of One's Own: Individual Rights and the Welfare State'', Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Core beliefs of classical liberals did not necessarily include democracy nor government by a majority vote by citizens because "there is nothing in the bare idea of majority rule to show that majorities will always respect the rights of property or maintain rule of law".Ryan, A. (1995): "Liberalism", In: Goodin, R. E. and Pettit, P., eds.: ''A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy'', Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, p. 293. For example, James Madison argued for a constitutional republic with protections for individual liberty over a pure democracy, reasoning that in a pure democracy a "common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole ... and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party".

In the late 19th century, classical liberalism developed into neoclassical liberalism

Neoclassical liberalism, also referred to as Arizona School liberalismNeoclassical liberal philosophers such as David Schmidtz, Jerry Gaus, John Tomasi, Kevin Vallier, Matt Zwolinski and Jason Brennan all have a connection to the University of A ...

, which argued for government to be as small as possible to allow the exercise of individual freedom. In its most extreme form, neoclassical liberalism advocated social Darwinism. Right-libertarianism is a modern form of neoclassical liberalism. However, Edwin Van de Haar states although libertarianism is influenced by classical liberal thought there are significant differences between them. Classical liberalism refuses to give priority to liberty over order and therefore does not exhibit the hostility to the state which is the defining feature of libertarianism. As such, right-libertarians believe classical liberals favor too much state involvement, arguing that they do not have enough respect for individual property rights and lack sufficient trust in the workings of the free market and its spontaneous order

Spontaneous order, also named self-organization in the hard sciences, is the spontaneous emergence of order out of seeming chaos. The term "self-organization" is more often used for physical changes and biological processes, while "spontaneous o ...

leading to support of a much larger state. Right-libertarians also disagree with classical liberals as being too supportive of central banks and monetarist

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national ...

policies.

Typology of beliefs

Friedrich Hayek identified two different traditions within classical liberalism, namely the British tradition and the French tradition. Hayek saw the British philosophersBernard Mandeville

Bernard Mandeville, or Bernard de Mandeville (; 15 November 1670 – 21 January 1733), was an Anglo-Dutch philosopher, political economist and satirist. Born in Rotterdam, Netherlands, he lived most of his life in England and used English for ...

, David Hume, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

, Adam Ferguson, Josiah Tucker and William Paley as representative of a tradition that articulated beliefs in empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

, the common law and in traditions and institutions which had spontaneously evolved but were imperfectly understood. The French tradition included Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal pu ...

, the Encyclopedists and the Physiocrats. This tradition believed in rationalism and sometimes showed hostility to tradition and religion. Hayek conceded that the national labels did not exactly correspond to those belonging to each tradition since he saw the Frenchmen Montesquieu, Benjamin Constant and Alexis de Tocqueville as belonging to the British tradition and the British Thomas Hobbes, Joseph Priestley, Richard Price and Thomas Paine as belonging to the French tradition. Hayek also rejected the label '' laissez-faire'' as originating from the French tradition and alien to the beliefs of Hume and Smith.

Guido De Ruggiero also identified differences between "Montesquieu and Rousseau, the English and the democratic types of liberalism" and argued that there was a "profound contrast between the two Liberal systems". He claimed that the spirit of "authentic English Liberalism" had "built up its work piece by piece without ever destroying what had once been built, but basing upon it every new departure". This liberalism had "insensibly adapted ancient institutions to modern needs" and "instinctively recoiled from all abstract proclamations of principles and rights". Ruggiero claimed that this liberalism was challenged by what he called the "new Liberalism of France" that was characterised by egalitarianism and a "rationalistic consciousness".

In 1848, Francis Lieber distinguished between what he called "Anglican and Gallican Liberty". Lieber asserted that "independence in the highest degree, compatible with safety and broad national guarantees of liberty, is the great aim of Anglican liberty, and self-reliance is the chief source from which it draws its strength". On the other hand, Gallican liberty "is sought in government ... . e French look for the highest degree of political civilisation in organisation, that is, in the highest degree of interference by public power".

History

Great Britain

Classical liberalism in Britain traces its roots to the Whigs andradicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

, and was heavily influenced by French physiocracy

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists who believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricultur ...

. Whiggery had become a dominant ideology following the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688 and was associated with supporting the British Parliament, upholding the rule of law, and defending landed property. The origins of rights were seen as being in an ancient constitution The ancient constitution of England was a 17th-century political theory about the common law, and the antiquity of the House of Commons, used at the time in particular to oppose the royal prerogative. It was developed initially by Sir Edward Coke, i ...

, which had existed from time immemorial. These rights, which some Whigs considered to include freedom of the press and freedom of speech, were justified by custom rather than as natural rights

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', ''fundamental'' and ...

. These Whigs believed that the power of the executive had to be constrained. While they supported limited suffrage, they saw voting as a privilege rather than as a right. However, there was no consistency in Whig ideology and diverse writers including John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

, David Hume, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

and Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

were all influential among Whigs, although none of them were universally accepted.

From the 1790s to the 1820s, British radicals concentrated on parliamentary and electoral reform, emphasising natural rights and popular sovereignty. Richard Price and Joseph Priestley adapted the language of Locke to the ideology of radicalism. The radicals saw parliamentary reform as a first step toward dealing with their many grievances, including the treatment of Protestant Dissenters, the slave trade, high prices, and high taxes. There was greater unity among classical liberals than there had been among Whigs. Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty, and equal rights. They believed these goals required a free economy with minimal government interference. Some elements of Whiggery were uncomfortable with the commercial nature of classical liberalism. These elements became associated with conservatism.

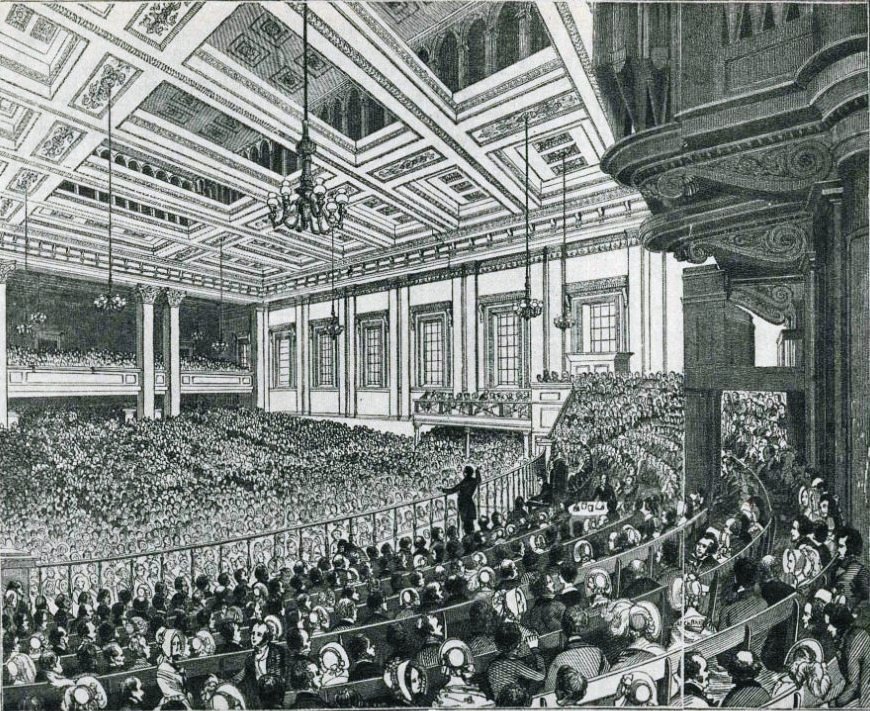

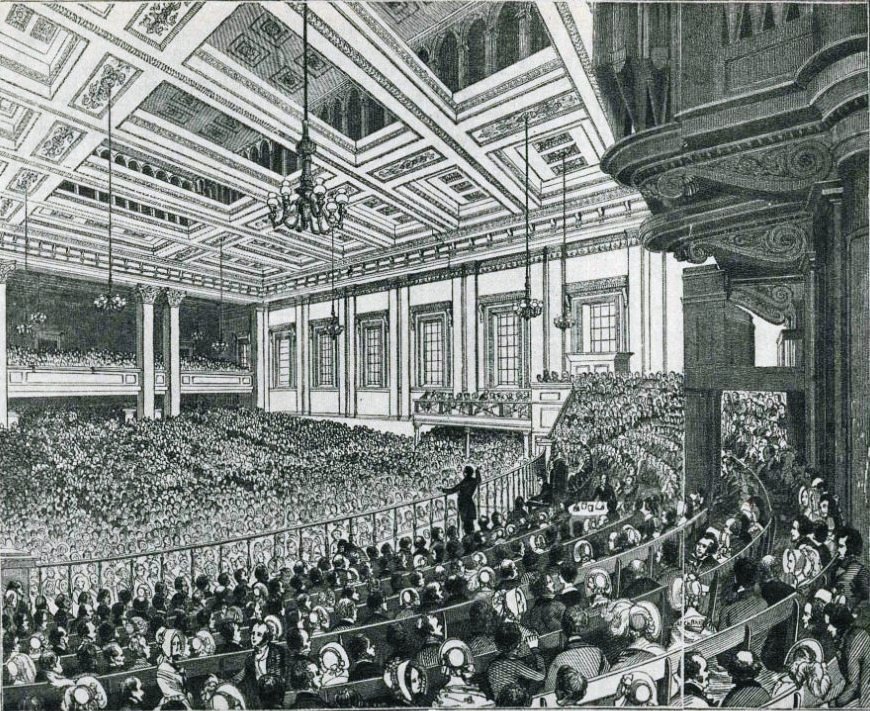

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, the Reform Act of 1832 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League brought together a coalition of liberal and radical groups in support of free trade under the leadership of Richard Cobden and John Bright, who opposed aristocratic privilege, militarism, and public expenditure and believed that the backbone of Great Britain was the yeoman farmer. Their policies of low public expenditure and low taxation were adopted by

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, the Reform Act of 1832 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League brought together a coalition of liberal and radical groups in support of free trade under the leadership of Richard Cobden and John Bright, who opposed aristocratic privilege, militarism, and public expenditure and believed that the backbone of Great Britain was the yeoman farmer. Their policies of low public expenditure and low taxation were adopted by William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

when he became Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

and later Prime Minister. Classical liberalism was often associated with religious dissent and nonconformism.

Although classical liberals aspired to a minimum of state activity, they accepted the principle of government intervention

Economic interventionism, sometimes also called state interventionism, is an economic policy position favouring government intervention in the market process with the intention of correcting market failures and promoting the general welfare of ...

in the economy from the early 19th century on, with passage of the Factory Acts

The Factory Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom to regulate the conditions of industrial employment.

The early Acts concentrated on regulating the hours of work and moral welfare of young children employed ...

. From around 1840 to 1860, ''laissez-faire'' advocates of the Manchester School and writers in '' The Economist'' were confident that their early victories would lead to a period of expanding economic and personal liberty and world peace, but would face reversals as government intervention and activity continued to expand from the 1850s. Jeremy Bentham and James Mill, although advocates of ''laissez-faire'', non-intervention in foreign affairs, and individual liberty, believed that social institutions could be rationally redesigned through the principles of utilitarianism. The Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

rejected classical liberalism altogether and advocated Tory democracy. By the 1870s, Herbert Spencer and other classical liberals concluded that historical development was turning against them. By the First World War, the Liberal Party had largely abandoned classical liberal principles.

The changing economic and social conditions of the 19th century led to a division between neo-classical and social (or welfare) liberals, who while agreeing on the importance of individual liberty differed on the role of the state. Neo-classical liberals, who called themselves "true liberals", saw Locke's '' Second Treatise'' as the best guide and emphasised "limited government" while social liberals supported government regulation and the welfare state. Herbert Spencer in Britain and William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and classical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University—where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology—and becam ...

were the leading neo-classical liberal theorists of the 19th century. The evolution from classical to social/welfare liberalism is for example reflected in Britain in the evolution of the thought of John Maynard Keynes.

United States

In the United States, liberalism took a strong root because it had little opposition to its ideals, whereas in Europe liberalism was opposed by many reactionary or feudal interests such as the nobility; the aristocracy, including army officers; the landed gentry; and the established church. Thomas Jefferson adopted many of the ideals of liberalism, but in the Declaration of Independence changed Locke's "life, liberty and property" to the more socially liberal " Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness". As the United States grew, industry became a larger and larger part of American life; and during the term of its first populist President, Andrew Jackson, economic questions came to the forefront. The economic ideas of the Jacksonian era were almost universally the ideas of classical liberalism. Freedom, according to classical liberals, was maximised when the government took a "hands off" attitude toward the economy. Historian Kathleen G. Donohue argues:the center of classical liberal theory n Europewas the idea of ''laissez-faire''. To the vast majority of American classical liberals, however, ''laissez-faire'' did not mean no government intervention at all. On the contrary, they were more than willing to see government provide tariffs, railroad subsidies, and internal improvements, all of which benefited producers. What they condemned was intervention on behalf of consumers.Leading magazine '' The Nation'' espoused liberalism every week starting in 1865 under the influential editor

Edwin Lawrence Godkin

Edwin Lawrence Godkin (2 October 183121 May 1902) was an Irish-born American journalist and newspaper editor. He founded ''The Nation'' and was the editor-in-chief of the ''New York Evening Post'' from 1883 to 1899.Eric Fettman, "Godkin, E.L." ...

(1831–1902). The ideas of classical liberalism remained essentially unchallenged until a series of depressions, thought to be impossible according to the tenets of classical economics

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith ...

, led to economic hardship from which the voters demanded relief. In the words of William Jennings Bryan, " You shall not crucify this nation on a cross of gold". Classical liberalism remained the orthodox belief among American businessmen until the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.Eric Voegelin, Mary Algozin, and Keith Algozin, "Liberalism and Its History", ''Review of Politics'' 36, no. 4 (1974): 504–520. . The Great Depression in the United States

In the United States, the Great Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and then spread worldwide. The nadir came in 1931–1933, and recovery came in 1940. The stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade of high un ...

saw a sea change in liberalism, with priority shifting from the producers to consumers. Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

represented the dominance of modern liberalism in politics for decades. In the words of Arthur Schlesinger Jr.:

Alan Wolfe summarizes the viewpoint that there is a continuous liberal understanding that includes both Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

and John Maynard Keynes:

The view that modern liberalism is a continuation of classical liberalism is not universally shared. James Kurth

James Kurth (born 1938) is the Claude C. Smith Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Swarthmore College, where he taught defense policy, foreign policy, and international politics. In 2004 Kurth also became the editor of '' Orbis'', a profes ...

, Robert E. Lerner

Robert E. Lerner (born 1940 in New York) is an American medieval historian and professor of history emeritus at Northwestern University.

Lerner gained his B.A. at the University of Chicago and his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1964, where he studied with ...

, John Micklethwait, Adrian Wooldridge and several other political scholars have argued that classical liberalism still exists today, but in the form of American conservatism. According to Deepak Lal, only in the United States does classical liberalism continue to be a significant political force through American conservatism. American libertarians also claim to be the true continuation of the classical liberal tradition.

Intellectual sources

John Locke

Central to classical liberal ideology was their interpretation of

Central to classical liberal ideology was their interpretation of John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

's ''Second Treatise of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (or ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, ...

'' and '' A Letter Concerning Toleration'', which had been written as a defence of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Although these writings were considered too radical at the time for Britain's new rulers, they later came to be cited by Whigs, radicals and supporters of the American Revolution. However, much of later liberal thought was absent in Locke's writings or scarcely mentioned and his writings have been subject to various interpretations. For example, there is little mention of constitutionalism, the separation of powers and limited government.

James L. Richardson identified five central themes in Locke's writing: individualism, consent, the concepts of the rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannica ...

and government as trustee, the significance of property and religious toleration. Although Locke did not develop a theory of natural rights, he envisioned individuals in the state of nature as being free and equal. The individual, rather than the community or institutions, was the point of reference. Locke believed that individuals had given consent to government and therefore authority derived from the people rather than from above. This belief would influence later revolutionary movements.

As a trustee, government was expected to serve the interests of the people, not the rulers; and rulers were expected to follow the laws enacted by legislatures. Locke also held that the main purpose of men uniting into commonwealths and governments was for the preservation of their property. Despite the ambiguity of Locke's definition of property, which limited property to "as much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of", this principle held great appeal to individuals possessed of great wealth.

Locke held that the individual had the right to follow his own religious beliefs and that the state should not impose a religion against Dissenters, but there were limitations. No tolerance should be shown for atheists, who were seen as amoral, or to Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, who were seen as owing allegiance to the Pope over their own national government.

Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

's '' The Wealth of Nations'', published in 1776, was to provide most of the ideas of economics, at least until the publication of John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

's '' Principles of Political Economy'' in 1848. Smith addressed the motivation for economic activity, the causes of prices and the distribution of wealth and the policies the state should follow to maximise wealth.

Smith wrote that as long as supply, demand, prices and competition were left free of government regulation, the pursuit of material self-interest, rather than altruism, would maximise the wealth of a society through profit-driven production of goods and services. An " invisible hand" directed individuals and firms to work toward the public good as an unintended consequence of efforts to maximise their own gain. This provided a moral justification for the accumulation of wealth, which had previously been viewed by some as sinful.

He assumed that workers could be paid wages as low as was necessary for their survival, which was later transformed by David Ricardo and Thomas Robert Malthus into the " iron law of wages". His main emphasis was on the benefit of free internal and international trade, which he thought could increase wealth through specialisation in production. He also opposed restrictive trade preferences, state grants of monopolies and employers' organisations and trade unions. Government should be limited to defence, public works and the administration of justice, financed by taxes based on income.

Smith's economics was carried into practice in the nineteenth century with the lowering of tariffs in the 1820s, the repeal of the Poor Relief Act that had restricted the mobility of labour in 1834 and the end of the rule of the East India Company over India in 1858.

Classical economics

In addition to Smith's legacy, Say's law, Thomas Robert Malthus' theories of population and David Ricardo's iron law of wages became central doctrines ofclassical economics

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith ...

. The pessimistic nature of these theories provided a basis for criticism of capitalism by its opponents and helped perpetuate the tradition of calling economics the "dismal science

The dismal science is a derogatory term for the discipline of economics. Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle used the phrase in his 1849 essay, ''Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question'', in contrast with the then-famil ...

".

Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of ...

was a French economist who introduced Smith's economic theories into France and whose commentaries on Smith were read in both France and Britain. Say challenged Smith's labour theory of value, believing that prices were determined by utility and also emphasised the critical role of the entrepreneur in the economy. However, neither of those observations became accepted by British economists at the time. His most important contribution to economic thinking was Say's law, which was interpreted by classical economists that there could be no overproduction in a market and that there would always be a balance between supply and demand. This general belief influenced government policies until the 1930s. Following this law, since the economic cycle was seen as self-correcting, government did not intervene during periods of economic hardship because it was seen as futile.

Malthus wrote two books, ''An Essay on the Principle of Population

An, AN, aN, or an may refer to:

Businesses and organizations

* Airlinair (IATA airline code AN)

* Alleanza Nazionale, a former political party in Italy

* AnimeNEXT, an annual anime convention located in New Jersey

* Anime North, a Canadian an ...

'' (published in 1798) and '' Principles of Political Economy'' (published in 1820). The second book which was a rebuttal of Say's law had little influence on contemporary economists. However, his first book became a major influence on classical liberalism. In that book, Malthus claimed that population growth would outstrip food production because population grew geometrically while food production grew arithmetically. As people were provided with food, they would reproduce until their growth outstripped the food supply. Nature would then provide a check to growth in the forms of vice and misery. No gains in income could prevent this and any welfare for the poor would be self-defeating. The poor were in fact responsible for their own problems which could have been avoided through self-restraint.

Ricardo, who was an admirer of Smith, covered many of the same topics, but while Smith drew conclusions from broadly empirical observations he used deduction, drawing conclusions by reasoning from basic assumptions While Ricardo accepted Smith's labour theory of value, he acknowledged that utility could influence the price of some rare items. Rents on agricultural land were seen as the production that was surplus to the subsistence required by the tenants. Wages were seen as the amount required for workers' subsistence and to maintain current population levels. According to his iron law of wages, wages could never rise beyond subsistence levels. Ricardo explained profits as a return on capital, which itself was the product of labour, but a conclusion many drew from his theory was that profit was a surplus appropriated by capitalists

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private pr ...

to which they were not entitled.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism provided the political justification for implementation of economic liberalism by British governments, which was to dominate economic policy from the 1830s. Although utilitarianism prompted legislative and administrative reform andJohn Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

's later writings on the subject foreshadowed the welfare state, it was mainly used as a justification for ''laissez-faire''.

The central concept of utilitarianism, which was developed by Jeremy Bentham, was that public policy should seek to provide "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". While this could be interpreted as a justification for state action to reduce poverty, it was used by classical liberals to justify inaction with the argument that the net benefit to all individuals would be higher.

Political economy

Classical liberals following Mill saw utility as the foundation for public policies. This broke both with conservative " tradition" and Lockean "natural rights", which were seen as irrational. Utility, which emphasises the happiness of individuals, became the central ethical value of all Mill-style liberalism. Although utilitarianism inspired wide-ranging reforms, it became primarily a justification for ''laissez-faire'' economics. However, Mill adherents rejected Smith's belief that the "invisible hand" would lead to general benefits and embraced Malthus' view that population expansion would prevent any general benefit and Ricardo's view of the inevitability of class conflict. ''Laissez-faire'' was seen as the only possible economic approach and any government intervention was seen as useless and harmful. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 was defended on "scientific or economic principles" while the authors of the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 were seen as not having had the benefit of reading Malthus. However, commitment to ''laissez-faire'' was not uniform and some economists advocated state support of public works and education. Classical liberals were also divided on free trade as Ricardo expressed doubt that the removal of grain tariffs advocated by Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League would have any general benefits. Most classical liberals also supported legislation to regulate the number of hours that children were allowed to work and usually did not oppose factory reform legislation. Despite the pragmatism of classical economists, their views were expressed in dogmatic terms by such popular writers as Jane Marcet and Harriet Martineau. The strongest defender of ''laissez-faire'' was ''The Economist'' founded by James Wilson in 1843. ''The Economist'' criticised Ricardo for his lack of support for free trade and expressed hostility to welfare, believing that the lower orders were responsible for their economic circumstances. ''The Economist'' took the position that regulation of factory hours was harmful to workers and also strongly opposed state support for education, health, the provision of water and granting of patents and copyrights. ''The Economist'' also campaigned against the Corn Laws that protected landlords in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports of cereal products. A rigid belief in ''laissez-faire'' guided the government response in 1846–1849 to the Great Famine in Ireland, during which an estimated 1.5 million people died. The minister responsible for economic and financial affairs, Charles Wood, expected that private enterprise and free trade, rather than government intervention, would alleviate the famine. The Corn Laws were finally repealed in 1846 by the removal of tariffs on grain which kept the price of bread artificially high, but it came too late to stop the Irish famine, partly because it was done in stages over three years.Free trade and world peace

Several liberals, including Smith and Cobden, argued that the free exchange of goods between nations could lead to world peace. Erik Gartzke states: "Scholars like Montesquieu, Adam Smith, Richard Cobden, Norman Angell, and Richard Rosecrance have long speculated that free markets have the potential to free states from the looming prospect of recurrent warfare". American political scientists John R. Oneal and Bruce M. Russett, well known for their work on the democratic peace theory, state: In '' The Wealth of Nations'', Smith argued that as societies progressed from hunter gatherers to industrial societies the spoils of war would rise, but that the costs of war would rise further and thus making war difficult and costly for industrialised nations: Cobden believed that military expenditures worsened the welfare of the state and benefited a small, but concentrated elite minority, summing up Britishimperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

, which he believed was the result of the economic restrictions of mercantilist policies. To Cobden and many classical liberals, those who advocated peace must also advocate free markets. The belief that free trade would promote peace was widely shared by English liberals of the 19th and early 20th century, leading the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who was a classical liberal in his early life, to say that this was a doctrine on which he was "brought up" and which he held unquestioned only until the 1920s. In his review of a book on Keynes, Michael S. Lawlor argues that it may be in large part due to Keynes' contributions in economics and politics, as in the implementation of the Marshall Plan and the way economies have been managed since his work, "that we have the luxury of not facing his unpalatable choice between free trade and full employment". A related manifestation of this idea was the argument of Norman Angell (1872–1967), most famously before World War I in ''The Great Illusion

''The Great Illusion'' is a book by Norman Angell, first published in the United Kingdom in 1909 under the title ''Europe's Optical Illusion'' and republished in 1910 and subsequently in various enlarged and revised editions under the title ''The ...

'' (1909), that the interdependence of the economies of the major powers was now so great that war between them was futile and irrational; and therefore unlikely.

Notable thinkers

* Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) * James Harrington (author) (1611-1677) *John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

(1632–1704)

* Montesquieu (1689-1755)

* Voltaire (1694–1778)

* Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)

* Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

(1723–1790)

* Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

* Anders Chydenius (1729–1803)

* Thomas Paine (1737–1809)

* Cesare Beccaria

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio (; 15 March 173828 November 1794) was an Italian criminologist, jurist, philosopher, economist and politician, who is widely considered one of the greatest thinkers of the Age ...

(1738-1794)

* Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal pu ...

(1743-1794)

* Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826)

* Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832)

* Gaetano Filangieri (1753-1788)

* Benjamin Constant (1767-1830)

* David Ricardo (1772–1823)

* Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859)

* Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872)

* John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

(1806-1872)

* William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898)

* Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

(1811-1873)

* Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901)

* Henry George (1839-1897)

* Friedrich Naumann (1860-1919)

* Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992)

* Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the cl ...

(1902-1994)

* Ayn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum;, . Most sources transliterate her given name as either ''Alisa'' or ''Alissa''. , 1905 – March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and p ...

(1905-1982)

* Raymond Aron (1905-1983)

* Milton Friedman (1912–2006)

* Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick (; November 16, 1938 – January 23, 2002) was an American philosopher. He held the Joseph Pellegrino University Professorship at Harvard University,

(1938-2002)

Classical liberal parties worldwide

Although generallibertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's e ...

, liberal-conservative and some right-wing populist political parties are also included in classical liberal parties in a broad sense, but only general classical liberal parties such as Germany's FDP, Denmark's Liberal Alliance and Thailand Democrat Party should be listed.

Classical liberal parties or parties with classical liberal factions

* Australia : Liberal Party of Australia, Liberal Democratic Party * Austria : NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum * Belgium : Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats * Brazil : New Party * Canada : People's Party * Chile : Evópoli, Amplitude * Denmark : Venstre, Liberal Alliance * Estonia :Estonian Reform Party

The Estonian Reform Party ( et, Eesti Reformierakond) is a liberal political party in Estonia. The party has been led by Kaja Kallas since 2018. It is colloquially known as the "Squirrel Party" ( et, Oravapartei).

It was founded in 1994 by Si ...

* France : La République En Marche!

Renaissance (RE), previously known as La République En Marche ! (frequently abbreviated LREM, LaREM or REM; translated as "The Republic on the Move" or "Republic Forward"), or sometimes called simply En Marche ! () as its original name, is a l ...

* Germany : Free Democratic Party Free Democratic Party is the name of several political parties around the world. It usually designates a party ideologically based on liberalism.

Current parties with that name include:

*Free Democratic Party (Germany), a liberal political party in ...

* Iceland : Reform Party

* Netherlands : People's Party for Freedom and Democracy

* New Zealand : New Zealand National Party

The New Zealand National Party ( mi, Rōpū Nāhinara o Aotearoa), shortened to National () or the Nats, is a centre-right political party in New Zealand. It is one of two major parties that dominate contemporary New Zealand politics, alongside ...

, ACT New Zealand

* Poland : Modern

* Portugal : Liberal Initiative

The Liberal Initiative ( pt, Iniciativa Liberal, , IL) is a liberal political party in Portugal currently led by João Cotrim de Figueiredo. In 2019, its debut year at the Portuguese legislative elections, the party won one seat in the Portugu ...

* Russia : PARNAS

* Serbia : Liberal Democratic Party of Serbia

The Liberal Democratic Party ( sr-cyrl, Либерално демократска партија, Liberalno demokratska partija, LDP) is a Liberalism, liberal List of political parties in Serbia, political party in Serbia. It is led by Čedomir ...

* South Africa : Democratic Alliance

* Sweden : Liberals

* Switzerland: FDP.The Liberals

* Thailand : Democrat Party

* Turkey : Liberal Democratic Party

* United Kingdom : Liberal Party

Historical classical liberal parties or parties with classical liberal factions (Since 1900s)

* Chile: Liberal Party * Germany : German Democratic Party * Japan :Liberal Party (1998)

The was a political party in Japan formed in 1998 by Ichirō Ozawa and Hirohisa Fujii. It is now defunct, having joined the Democratic Party of Japan in 2003.

The Liberal Party were part of the Japanese liberal Parties genealogy, neolibera ...

, Liberal League

* South Korea : New Democratic Party

The New Democratic Party (NDP; french: Nouveau Parti démocratique, NPD) is a federal political party in Canada. Widely described as social democratic,The party is widely described as social democratic:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* t ...

* Switzerland : Free Democratic Party of Switzerland

french: Parti radical-démocratique it, Partito Liberale Radicale rm, Partida liberaldemocrata svizra

, logo = Free Democratic Party of Switzerland logo French.png

, logo_size = 200px

, foundation =

, dissolution =

...

, Liberal Party of Switzerland

* United Kingdom : Liberal Party''The Times'' (31 December 1872), p. 5.

See also

* Age of Enlightenment * Austrian School * Bourbon Democrat ** National Democratic Party *Classical economics

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith ...

* Cultural liberalism

* Classical radicalism

** Modern liberalism

* Classical republicanism

* Constitutionalism

* Constitutional liberalism

* Conservative liberalism

* Economic liberalism

* Fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is a political and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility with an ideological basis in capitalism, individualism, limited government, and ''laissez-faire'' economics.M. O. Dickerson et al., ''An ...

* Friedrich Naumann Foundation

* Georgism

* Gladstonian liberalism

* Jeffersonian democracy

* Liberal conservatism

Liberal conservatism is a political ideology combining conservative policies with liberal stances, especially on economic issues but also on social and ethical matters, representing a brand of political conservatism strongly influenced by libe ...

* Liberal democracy

* Liberalism in Europe

* Libertarianism

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

** Left-libertarianism

** Right-libertarianism

* List of liberal theorists

* Neoclassical liberalism

Neoclassical liberalism, also referred to as Arizona School liberalismNeoclassical liberal philosophers such as David Schmidtz, Jerry Gaus, John Tomasi, Kevin Vallier, Matt Zwolinski and Jason Brennan all have a connection to the University of A ...

* Neoliberalism

* Night-watchman state

* Orléanist

* Physiocracy

Physiocracy (; from the Greek for "government of nature") is an economic theory developed by a group of 18th-century Age of Enlightenment French economists who believed that the wealth of nations derived solely from the value of "land agricultur ...

* Political individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relianc ...

* Rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannica ...

* Separation of powers

* Whig history

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Alan Bullock and Maurice Shock, ed. (1967). ''The Liberal Tradition: From Fox to Keynes''. Oxford. Clarendon Press. * * Katherine Henry (2011). ''Liberalism and the Culture of Security: The Nineteenth-Century Rhetoric of Reform''. University of Alabama Press; draws on literary and other writings to study the debates over liberty and tyranny. * Donald Markwell (2006). '' John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace''. Oxford, England. Oxford University Press. . * * Gustav Pollak, ed. (1915)''Fifty Years of American Idealism: 1865–1915''

short history of '' The Nation'' plus numerous excerpts, most by

Edwin Lawrence Godkin

Edwin Lawrence Godkin (2 October 183121 May 1902) was an Irish-born American journalist and newspaper editor. He founded ''The Nation'' and was the editor-in-chief of the ''New York Evening Post'' from 1883 to 1899.Eric Fettman, "Godkin, E.L." ...

.

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Classical Liberalism Liberalism 19th-century introductions Economic liberalism Ideologies of capitalism Liberalism in Europe Political ideologies