Clara Gertrud Wichmann on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Clara Gertrud Wichmann (17 August 1885 – 15 February 1922) was a

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

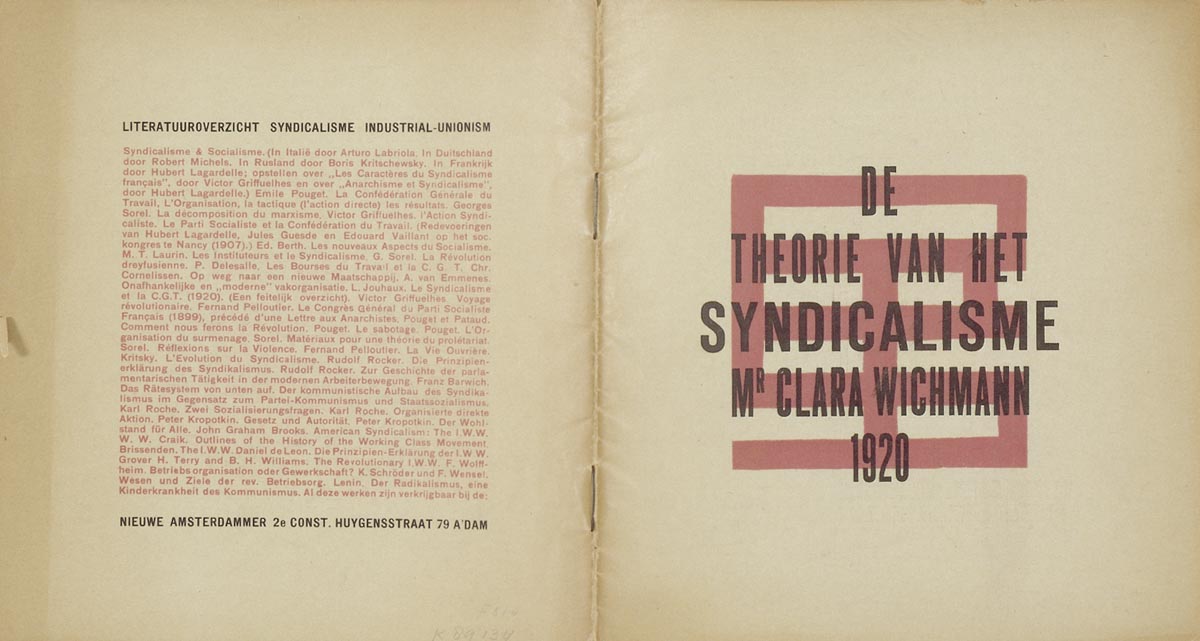

;Posthumously published

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

;Posthumously published

*

*

*

*

*

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

–Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

and anarchist feminist activist, who became a leading advocate of criminal justice reform

Criminal justice reform is the reform of criminal justice systems.

Stated reasons for criminal justice reform include reducing crime statistics, racial profiling, police brutality, overcriminalization, mass incarceration, under-reporting, and ...

and prison abolition

The police and prison abolition movement is a political movement, mostly active in the United States, that advocates replacing policing and prison system with other systems of public safety. Police and prison abolitionists believe that policing a ...

in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

.

Biography

In 1885, Clara Wichmann was born inHamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

, the daughter of Carl Ernst Arthur Wichmann and Johanna Theresa Henriette Zeise. In 1902, she studied philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy and t ...

. She went on to study law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

between 1903 and 1905, during which she first became critical of the criminal justice system

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other ...

and started to push for its reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

.

She developed a theory of criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It proscribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and Well-being, welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal l ...

that advocated for the abolition of prisons

The prison abolition movement is a network of groups and activists that seek to reduce or eliminate prisons and the prison system, and replace them with systems of rehabilitation and education that do not focus on punishment and government instit ...

and punitive justice, which she elaborated in her thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

, graduating as a Doctor of Law

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

in 1912. In 1914, she was employed by the Dutch Statistics Office as a lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

, but was soon promoted to deputy director of the Social Welfare Institute. She collaborated with Jacques de Roos on compiling criminal statistics, and in 1919, she succeeded de Roos as head of the Judicial Statistics Department.

During her studies, she had joined the Dutch feminist movement in 1908, co-founding the () and working as its secretary until 1911. She was also on the board of the (). She went on to participate in the opposition to World War I

Opposition to World War I was widespread during the conflict and included socialists, such as anarchists, syndicalists, and Marxists, as well as Christian pacifists, anti-colonial nationalists, feminists, Intellectual, intellectuals, and the w ...

and became an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

in 1918. She also studied the history of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

and, from 1914 to 1918, co-authored the encyclopaedia

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles or entries that are arranged alphabetically by artic ...

() with Cornelia Werker-Beaujon.

She became an activist in the prison abolition movement and campaigned against punitive justice, which she described as "a blot of backwardness, coarseness, shallowness and harshness." In 1919, she established the ''Comité van Actie tegen de bestaande opvattingen omtrent Misdaad en Straf'' () and co-founded the ''Bond van Revolutionair Socialistische Intellectuelen'' (). On 21 March 1920, she gave a public speech in which she asserted that crime was rooted in social injustice, and that equitable social relations would make almost all criminal acts disappear. That same year, she co-founded the (). She wrote numerous articles for the organisation's newspaper, ''De Vrije Communist'' (), in which she called for strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

s as a means of non-violent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, constructiv ...

against social injustice.

In 1921, she married Jonas Meijer, a pacifist conscientious objector. The couple were close to the Dutch anarchists and Bart de Ligt

Bartholomeus de Ligt (17 July 1883 – 3 September 1938) was a Dutch anarcho-pacifist and antimilitarist. He is chiefly known for his support of conscientious objectors.

Life and work

Born on 17 July 1883 in Schalkwijk, Utrecht, his father wa ...

. Wichmann died in 1922, a few hours after giving birth to her daughter Hetty Clara Passchier-Meijer.

Legacy

Jonas Meijer continued to publish Wichmann's work after her death. Though anatheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

, he was Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

by birth and survived the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

by going into hiding in Amsterdam. Hetty Clara survived the war and helped hide a Jewish family in Leiden

Leiden ( ; ; in English language, English and Archaism, archaic Dutch language, Dutch also Leyden) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Provinces of the Nethe ...

whilst working with the resistance. After the war she became a doctor and until her death remained actively involved in the publishing and archiving of her mother's work. In 1987, the Clara Wichmann Institute, which advocated for women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

, was opened in her name. In 2005, the institute studied the issue of positive discrimination

Affirmative action (also sometimes called reservations, alternative access, positive discrimination or positive action in various countries' laws and policies) refers to a set of policies and practices within a government or organization seeking ...

, or discrimination against women

A woman is an adult female human. Before adulthood, a female child or adolescent is referred to as a girl.

Typically, women are of the female sex and inherit a pair of X chromosomes, one from each parent, and women with functional uteruses ...

on religious grounds, and its relationship with international treaties on gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality, gender egalitarianism, or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making, an ...

. That same year, Ellie Smolenaars published ''Passie voor vrijheid'', a biography on Wichmann.

Selected works

See also

*Anarchism in the Netherlands

Anarchism in the Netherlands originated in the second half of the 19th century. Its roots lay in the radical and revolutionary ideologies of the labor movement, in anti-authoritarian socialism, the free thinkers and in numerous associations and o ...

References

Further reading

* *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wichmann, Clara 1885 births 1922 deaths People from Hamburg Emigrants from the German Empire Immigrants to the Netherlands Dutch anarchists Dutch atheists Dutch encyclopedists Dutch feminists Dutch pacifists Dutch women non-fiction writers Anarcha-feminists Anarchist theorists Anarchist writers Anarcho-syndicalists Prison abolitionists Socialist feminists 20th-century anarchists 20th-century atheists 20th-century Dutch non-fiction writers 20th-century Dutch women lawyers 20th-century Dutch women writers