Cicely Williams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cicely Delphine Williams, OM, CMG, FRCP (2 December 1893 – 13 July 1992) was a Jamaican physician, most notable for her discovery and research into

"Obituary: Dr Cicely Williams"

The Independent UK. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

"Dr Cicely Williams: Jamaica's Gift to the Field for Maternal and Child Health Care 1893–1992"

. Jamaica Gleaner. Retrieved 28 July 2012. At 13 she left Jamaica to be educated in England, beginning her studies in

"Book review: Retired, Except on Demand: The Life of Dr Cicely Williams, by Sally Craddock"

Archives of Disease in Childhood (hosted by British Medical Journal Online). Retrieved 28 July 2012. She deferred her place at college, as she returned to Jamaica to help her parents after a devastating series of earthquakes and hurricanes. After the death of her father in 1916 Williams, then 23, returned to Oxford and began studying medicine. Williams was one of the first females admitted into the course, only because of the dearth of male students caused by

"Listening to the Ga: Cicely Williams' Discovery of Kwashiorkor on the Gold Coast"

World Public Health Nutrition Association. Retrieved 29 July 2012. Her role on the Gold Coast was to treat acutely ill infants and children, and give advice at a clinic level. Faced with the shocking rate of death and illness in the community, Williams trained nurses to do out-reach visits, and created well-baby visits for the local community. She also began a patient information card system to assist with record keeping. Williams, while supportive of modern medicine and scientific techniques, was one of the few colonial physicians who gave credence to traditional medicine and local knowledge. Williams noted that while the

"There is nothing mysterious about kwashiorkor"

British Medical Journal. Retrieved 28 July 2012. Her findings- that the condition was due to a lack of protein in the diets of weanlings after the arrival of a new baby- were published in the ''

kwashiorkor

Kwashiorkor ( , is also ) is a form of severe protein malnutrition characterized by edema and an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates. It is thought to be caused by sufficient calorie intake, but with insufficient protein consumption (or lac ...

, a condition of advanced malnutrition, and her campaign against the use of sweetened condensed milk

Condensed milk is cow's milk from which water has been removed (roughly 60% of it). It is most often found with sugar added, in the form of sweetened condensed milk, to the extent that the terms "condensed milk" and "sweetened condensed milk" are o ...

and other artificial baby milks as substitutes for human breast milk

Breast milk (sometimes spelled as breastmilk) or mother's milk is milk produced by the mammary glands in the breasts of women. Breast milk is the primary source of nutrition for newborn infants, comprising fats, proteins, carbohydrates, and a va ...

.

One of the first female graduates of Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

, Williams was instrumental in advancing the field of maternal and child health in developing nations, and in 1948 became the first director of Mother and Child Health (MCH) at the newly created World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

(WHO). She once remarked that "if you learn your nutrition from a biochemist, you're not likely to learn how essential it is to blow a baby's nose before expecting him to suck."Stanton, Jennifer (16 July 1992)"Obituary: Dr Cicely Williams"

The Independent UK. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

Early life

Cicely Delphine Williams was born in Kew Park, Darliston, Westmoreland,Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

into a family which had lived there for generations. She was the daughter of James Rowland Williams (1860-1916), and Margaret Emily Caroline Farewell (1862-1953). Her father is said to have remarked, when Cicely was nine years old, that she had better become a lady doctor as she was unlikely to find a husband.Tortello, Rebecca (26 November 2002)"Dr Cicely Williams: Jamaica's Gift to the Field for Maternal and Child Health Care 1893–1992"

. Jamaica Gleaner. Retrieved 28 July 2012. At 13 she left Jamaica to be educated in England, beginning her studies in

Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

and was then awarded a place at Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The colle ...

when she was 19.Gairdner, Douglas (1984)"Book review: Retired, Except on Demand: The Life of Dr Cicely Williams, by Sally Craddock"

Archives of Disease in Childhood (hosted by British Medical Journal Online). Retrieved 28 July 2012. She deferred her place at college, as she returned to Jamaica to help her parents after a devastating series of earthquakes and hurricanes. After the death of her father in 1916 Williams, then 23, returned to Oxford and began studying medicine. Williams was one of the first females admitted into the course, only because of the dearth of male students caused by

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. She graduated in 1923.

Williams qualified from King's College Hospital in 1923, at 31, and worked for two years at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children was based in Bethnal Green in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, London. In 1996, the hospital became part of The Royal Hospitals NHS Trust, later renamed Barts and The London NHS Trust. In 1998, the se ...

, in Hackney. It was here that Williams decided to specialise in paediatrics, acknowledging that to be an effective physician she must have first hand knowledge of a child's home environment and background, a notion which would come to define her medical practice.

Due to the end of World War I, and the return of male physicians, Williams found it difficult to find a medical position following graduation. She worked for a term in Salonika with Turkish refugees. She completed a course at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public university, public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a constituent college, member institution of the University of London that specialises in public hea ...

(LSHTM) from 1928–9 and afterwards applied to the Colonial Medical Service, and in 1929 was posted to the Gold Coast (present day Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

).

Colonial Medical Service

Williams was employed specifically as a "Woman Medical Officer"- a distinction she disagreed with, not least because it meant she was paid a lower rate than her male counterparts.Stanton, J (May 2012)"Listening to the Ga: Cicely Williams' Discovery of Kwashiorkor on the Gold Coast"

World Public Health Nutrition Association. Retrieved 29 July 2012. Her role on the Gold Coast was to treat acutely ill infants and children, and give advice at a clinic level. Faced with the shocking rate of death and illness in the community, Williams trained nurses to do out-reach visits, and created well-baby visits for the local community. She also began a patient information card system to assist with record keeping. Williams, while supportive of modern medicine and scientific techniques, was one of the few colonial physicians who gave credence to traditional medicine and local knowledge. Williams noted that while the

child mortality

Child mortality is the death of children under the age of five. The child mortality rate (also under-five mortality rate) refers to the probability of dying between birth and exactly five years of age expressed per 1,000 live births.

It encompa ...

was high, newborns were not represented nearly as highly as toddlers between two and four years. The repeated presentation of young children with swollen bellies and stick thin limbs who very often died despite treatment, piqued Dr Williams' interest. This condition was often diagnosed as pellagra

Pellagra is a disease caused by a lack of the vitamin niacin (vitamin B3). Symptoms include inflamed skin, diarrhea, dementia, and sores in the mouth. Areas of the skin exposed to friction and radiation are typically affected first. Over tim ...

, a vitamin deficiency, but Williams disagreed, and carried out autopsies on the dead children at great personal risk to herself (there were no antibiotics in colonial Ghana, and she became severely ill with streptococcal haemolysis from a cut during one such procedure). Williams asked the local women what they called this condition, and was told ''kwashiorkor

Kwashiorkor ( , is also ) is a form of severe protein malnutrition characterized by edema and an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates. It is thought to be caused by sufficient calorie intake, but with insufficient protein consumption (or lac ...

'', which Williams translated as "disease of the deposed child".Konotey-Ahulu, Felix (14 May 2005)"There is nothing mysterious about kwashiorkor"

British Medical Journal. Retrieved 28 July 2012. Her findings- that the condition was due to a lack of protein in the diets of weanlings after the arrival of a new baby- were published in the ''

Archives of Disease in Childhood

''Archives of Disease in Childhood'' is a peer review, peer-reviewed medical journal published by the BMJ Group and covering the field of paediatrics. It is the official journal of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

Scope

''Archi ...

'' in 1933.

Her colleagues in the colonies were quick to oppose her claims, particularly H.S. Stannus, regarded as an expert on African nutritional deficiency, and Williams thus followed up her paper with another, more directly contrasting kwashiorkor and pellagra, published in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal, founded in England in 1823. It is one of the world's highest-impact academic journals and also one of the oldest medical journals still in publication.

The journal publishes ...

'' in 1935. This did little to sway medical opinion, and colonial physicians continued to avoid using the term kwashiorkor, or even acknowledge that it was a distinct condition from pellagra, despite the continued deaths of thousands of children who were being treated for the latter condition. Williams remarked about the ongoing issue "These men in Harley Street

Harley Street is a street in Marylebone, Central London, named after Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.

Williams felt that kwashiorkor was a disease caused mostly through a lack of knowledge and information, and her desire to combine preventive and curative medicine caused her to clash with her superiors and in 1936, after over seven years of service on the Gold Coast, she was transferred 'in disgrace' to Malaya, to lecture at the

"Breastfeeding Pioneer: Cicely Williams"

LaLeche League International (Asia). Retrieved 26 July 2012.

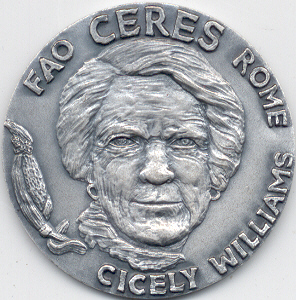

Retrieved 23 July 2018. 1976 FAO Ceres Medal.

In 1986 Dr Williams was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science from the

1976 FAO Ceres Medal.

In 1986 Dr Williams was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science from the

Wellcome Collection

{{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, Cicely 1893 births 1992 deaths Alumni of King's College London Jamaican paediatricians People from Westmoreland Parish Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica) Recipients of the James Spence Medal Alumni of Somerville College, Oxford Women medical researchers Colonial Medical Service officers Jamaican emigrants to the United Kingdom Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

University of Singapore

The National University of Singapore (NUS) is a national public research university in Singapore. It was officially established in 1980 by the merging of the University of Singapore and Nanyang University.

The university offers degree program ...

.Knutson, Tanja (June 2005)"Breastfeeding Pioneer: Cicely Williams"

LaLeche League International (Asia). Retrieved 26 July 2012.

Malaya and World War II

In Malaya, Williams found a very different health care problem: The mortality of newborn infants was extremely high. She became incensed after learning that companies were employing women dressed as nurses to go to tenement houses and convince new mothers thatsweetened condensed milk

Condensed milk is cow's milk from which water has been removed (roughly 60% of it). It is most often found with sugar added, in the form of sweetened condensed milk, to the extent that the terms "condensed milk" and "sweetened condensed milk" are o ...

was a preferable replacement for their own milk. This practice was illegal in England and Europe, but Nestlé

Nestlé S.A. ( ) is a Swiss multinational food and drink processing conglomerate corporation headquartered in Vevey, Switzerland. It has been the largest publicly held food company in the world, measured by revenue and other metrics, since 20 ...

was exporting the milk to Malaysia and advertising it as "ideal for delicate infants". In 1939 Williams was invited to address the Singapore Rotary Club, the chairman of which was also the president of Nestlé

Nestlé S.A. ( ) is a Swiss multinational food and drink processing conglomerate corporation headquartered in Vevey, Switzerland. It has been the largest publicly held food company in the world, measured by revenue and other metrics, since 20 ...

, and gave a speech titled "Milk and Murder," famously saying:

:''"Misguided propaganda on infant feeding should be punished as the most miserable form of sedition; these deaths should be regarded as murder."''

Williams oversaw the development and running of a primary health care center in the province of Trengganu

Terengganu (; Terengganu Malay: ''Tranung'', formerly spelled Trengganu or Tringganu) is a sultanate and federal state of Malaysia. The state is also known by its Arabic honorific, ''Dāru l- Īmān'' ("Abode of Faith"). The coastal city of K ...

in northeastern Malaya, and was responsible for 23 other doctors and some 300,000 patients. In 1941 the Japanese invaded, and Williams was forced to trek to Singapore to safety. Shortly after her arrival, Singapore too fell to the Japanese, and she was interned first at the Sime Road camp, and then later taken to Changi Prison

Changi Prison Complex, often known simply as Changi Prison, is a prison complex in the namesake district of Changi in the eastern part of Singapore. It is the oldest and largest prison in the country, covering an area of about . Opened in 193 ...

with 6,000 other prisoners. She was jailed for three-and-a-half years at Changi, and became one of the camp leaders, a position that led to her being removed for six months to the Kempe Tai headquarters where she was tortured, starved and kept in cages with dying men. Williams suffered dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

, beriberi

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (vitamin B1). A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi. The name beriberi was possibly borrowed in the 18th century from the Sinhalese phrase (bæri bæri, “I canno ...

(which left her feet numb for the rest of her life) and when the war was declared over in 1945, she was in the hospital, near death.

On her return to England, Williams wrote a report titled ''Nutritional conditions among women and children in internment in the civilian camp'', noting that:

:''"20 babies were born, 20 babies were breastfed, 20 babies survived, you can't do better than that".''

Later years

In 1948, Williams was made head of the new Maternal and Child Health (MCH) division of theWorld Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

in Geneva, and later transferred back to Malaya to head all maternal and child welfare services in South-East Asia. In 1950, she oversaw the commission of an international survey into kwashiorkor across 10 nations in sub-Saharan Africa. This study found that the condition carried such a health burden that it represented "the most serious and widespread nutritional disorder known to medical or nutritional science." In her years with the organisation she lectured and advised on MCH in over 70 countries and was influential in promoting the advantages of local knowledge and resources as key to achieving health and wellness in local communities.

Following an outbreak of "vomiting sickness" in Jamaica in 1951 the Government ordered an investigation "to improve child care and investigate the causes of food poisoning". Between 1951-1953 Dr. Williams coordinated this research and the results were published. This eventually led to the identification of the hypoglycaemic effects of unripe ackee

The ackee (''Blighia sapida''), also known as acki, akee, or ackee apple, is a fruit of the Sapindaceae ( soapberry) family, as are the lychee and the longan. It is native to tropical West Africa. The scientific name honours Captain William B ...

.

From 1953–1955 she was a senior lecturer in Nutrition at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a member institution of the University of London that specialises in public health and tropical medicine. The institu ...

, her alma mater. In 1960 Williams' became Professor of Maternal and Child Services at the American University of Beirut

The American University of Beirut (AUB; ) is a private, non-sectarian, and independent university chartered in New York with its main campus in Beirut, Lebanon. AUB is governed by a private, autonomous board of trustees and offers programs le ...

. She stayed for four years, and in her time worked with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

(UNRWA) with the Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

. She also worked with at risk communities in Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

.

Awards and honours

In 1965, Williams was awarded the James Spence Gold Medal of theRoyal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, often referred to as the RCPCH, is the professional body for paediatricians (doctors specialising in child health) in the United Kingdom. It is responsible for the postgraduate training of pa ...

for the discovery of Kwashiorkor

Kwashiorkor ( , is also ) is a form of severe protein malnutrition characterized by edema and an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates. It is thought to be caused by sufficient calorie intake, but with insufficient protein consumption (or lac ...

, a nutritional disease, in Accra

Accra (; or ''Gaga''; ; Ewe: Gɛ; ) is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , had a population of ...

and for recognising malnutrition was more likely to be caused by lack of nutritional knowledge rather than poverty.

In 1968, Dr Williams was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG), and introduced to Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony at Buckingham Palace. The Queen reputedly remarked: "I can't remember where you've been." To which Williams replied, "Many places." "Doing what?" asked Her Majesty. With typical modesty, Williams replied, "Mostly looking after children."Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia (2002)Retrieved 23 July 2018.

1976 FAO Ceres Medal.

In 1986 Dr Williams was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science from the

1976 FAO Ceres Medal.

In 1986 Dr Williams was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Science from the University of Ghana

The University of Ghana is a public university located in Accra, Ghana. It is the oldest public university in the country.

The university was founded in 1948 as the University College of the Gold Coast in the British colony of the Gold Coast ...

, for her "love, care and devotion to sick children" and her citation mentioned that during her time as a colonial physician "it became necessary to have the police keep order among the surging patients."

Legacy

Many authors have written of her achievements. In 2005, a Ghanaian physician Felix Konotey-Ahulu, wrote to ''The Lancet'' in praise of Dr Williams' ability to identify and acknowledge the social context of diseases such as kwashiorkor, he mentions that her translation of the concept had yet to be bettered almost 70 years later, and commended her for her respect for local traditions, as evidenced by her referring to kwashiorkor by its local name. Another article also recognised her for pioneering the field of maternal and child specific medicine, as during her early days in Ghana, such works was devalued as 'women's work' and outside the realms of proper modern medicine. She took copious photographs and notes cataloguing her time in Ghana, and admired the mothering skills of the native women, remarking that " he babyis carried about on the mother's back, a position it loves, it sleeps close beside her, it is nourished whenever it cries, and on the whole it does remarkably well on this treatment", while traditional British parenting recommended the separation of mothers from their infants whenever possible. The article concludes by recognising Williams' contribution to the field of primary health care, stating that after the war and into the modern day, her views becoming the 'gospel for the next generation'. In writing about Africans of the Gold Coast, Dr Williams noted: "compared to the white races, he seems to lack initiative and constructive ideas, although he may be shrewd to judge the attainment of others... he is almost invariably dishonest"Carothers, J.C. (1953) "The African Mind in Health and Disease: a Study in Ethnopsychiatry". Geneva: World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/41138/1/WHO_MONO_17_%28part1%29.pdf In 1983 Sally Craddock published a biography entitled ''Retired, Except on Demand: The Life of Dr Cicely Williams'', taking the title from Williams' declaration after her 'official retirement' at the age of 71. Dr Williams however continued actively travelling and speaking into her early 90s. In 1986 a book entitled ''Primary Health Care Pioneer: The Selected Works of Dr Cicely D. Williams'' pronounced her as having fulfilled the "physician's dream" of diagnosing, investigating and discovering the cure for a new disease, and commended her for doing such in an environment without modern medical resources.Baumslag, Naomi (October 1986) "Primary Health Care Pioneer: The Selected Works of Dr. Cicely D. Williams". American Public Health Association.Death

Williams died in Oxford in 1992 at the age of 98.References

External links

Williams's archives are now held aWellcome Collection

{{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, Cicely 1893 births 1992 deaths Alumni of King's College London Jamaican paediatricians People from Westmoreland Parish Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica) Recipients of the James Spence Medal Alumni of Somerville College, Oxford Women medical researchers Colonial Medical Service officers Jamaican emigrants to the United Kingdom Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George