Christian Rakovsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian Georgiyevich Rakovsky ( – September 11, 1941), Bulgarian name Krastyo Georgiev Rakovski, born Krastyo Georgiev Stanchov, was a

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

n-born socialist revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

, a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

politician and Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

diplomat and statesman; he was also noted as a journalist, physician, and essayist. Rakovsky's political career took him throughout the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

and into France and Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

; for part of his life, he was also a Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

n citizen.

A lifelong collaborator of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, he was a prominent activist of the Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

, involved in politics with the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party, Romanian Social Democratic Party, and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

. Rakovsky was expelled at different times from various countries as a result of his activities, and, during World War I, became a founding member of the Revolutionary Balkan Social Democratic Labor Federation while helping to organize the Zimmerwald Conference. Imprisoned by Romanian authorities, he made his way to Russia, where he joined the Bolshevik Party

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

after the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, and unsuccessfully attempted to generate a communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, the term socialism can be used to indicate an intermediate stage between ...

in the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania () was a constitutional monarchy that existed from with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King of Romania, King Carol I of Romania, Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian royal family), until 1947 wit ...

. Subsequently, he was a founding member of the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

, served as head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

in the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, and took part in negotiations at the Genoa Conference.

He came to oppose Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and rallied with the Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

, being marginalized inside the government and sent as Soviet ambassador to London and Paris, where he was involved in renegotiating financial settlements. He was ultimately recalled from France in autumn 1927, after signing his name to a controversial Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

platform which endorsed world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

. Credited with having developed the Trotskyist critique of Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

as "bureaucratic centrism", Rakovsky was subject to internal exile. Submitting to Stalin's leadership in 1934 and being briefly reinstated, he was nonetheless implicated in the Trial of the Twenty One (part of the Moscow Trials), imprisoned, and executed by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

during World War II. He was rehabilitated in 1988, during the Soviet ''Glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'' period.

Names

Rakovsky's original Bulgarian name was Krastyo Georgiev Stanchev (Кръстьо Георгиев Станчев), which he himself changed to ''Krastyo Rakovski'' (Кръстьо Раковски), being a grandnephew of the Bulgarian national hero Georgi Rakovski. The usual form his first name took in Romanian was ''Cristian'' (occasionally rendered as ''Christian''), while his last name was spelled ''Racovski'', ''Racovschi'', or ''Rakovski''. His given name was occasionally rendered as ''Ristache'', an antiquatedhypocoristic

A hypocorism ( or ; from Ancient Greek ; sometimes also ''hypocoristic''), or pet name, is a name used to show affection for a person. It may be a diminutive form of a person's name, such as '' Izzy'' for Isabel or '' Bob'' for Robert, or it ...

—he was known as such to his acquaintance, writer Ion Luca Caragiale

Ion Luca Caragiale (; According to his birth certificate, published and discussed by Constantin Popescu-Cadem in ''Manuscriptum'', Vol. VIII, Nr. 2, 1977, pp. 179–184 – 9 June 1912), commonly referred to as I. L. Caragiale, was a Romanians, ...

.Cioculescu, pp. 28, 46, 246–248

In Russian, his full name, including patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, b ...

, was ''Khristian Georgievich Rakovsky'' (Христиан Георгиевич Раковский). ''Christian'' (as well as ''Cristian'' and ''Kristian'') is an approximate rendition of ''Krastyo'' (the Bulgarian for "cross"), as used by Rakovsky himself.Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans'' In Ukrainian, Rakovsky's name is rendered as Християн Георгійович Раковський, and usually transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one writing system, script to another that involves swapping Letter (alphabet), letters (thus ''wikt:trans-#Prefix, trans-'' + ''wikt:littera#Latin, liter-'') in predictable ways, such as ...

as ''Khrystyian Heorhiiovych Rakovskyi''.

During his lifetime, he was also known under the pseudonyms ''H. Insarov'' and ''Grigoriev'', which he used in signing several articles for the Russian-language press.

Biography

Revolutionary beginnings

Christian Rakovsky was born to a wealthy Bulgarian family in Gradets — near Kotel — at the time still part of Ottoman-ruledRumelia

Rumelia (; ; ) was a historical region in Southeastern Europe that was administered by the Ottoman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Balkans. In its wider sense, it was used to refer to all Ottoman possessions and Vassal state, vassals in E ...

. He was, on his mother's side, the grandnephew of Georgi Sava Rakovski

Georgi Stoykov Rakovski () (1821 – 9 October 1867), known also Georgi Sava Rakovski (), born Sabi Stoykov Popovich (), was a 19th-century Bulgarian revolutionary, freemason, writer and an important figure of the Bulgarian National Revival ...

, a revolutionary hero of the Bulgarian National Revival

The Bulgarian Revival (, ''Balgarsko vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and ), sometimes called the Bulgarian National Revival, was a period of socio-economic development and national integration among Bulgarian pe ...

;Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Rakovsky, "An Autobiography"; Upson Clark that side of his family also included Georgi Mamarchev, who had fought against the Ottomans in the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army () was the army of the Russian Empire, active from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was organized into a standing army and a state militia. The standing army consisted of Regular army, regular troops and ...

.Rakovsky, "An Autobiography" Rakovsky's father was a merchant who belonged to the Democratic Party.

He later stated that, as early as his childhood years, he had felt a special admiration towards Russia, and that he had been impressed by witnessing, at age 5, the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

and Russian presence (he claimed to have met General Eduard Totleben during the conflict).

Although his parents moved to the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania () was a constitutional monarchy that existed from with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King of Romania, King Carol I of Romania, Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian royal family), until 1947 wit ...

in 1880, settling in Gherengic (Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

), he completed his education in newly emancipated Bulgaria.Rakovsky, ''An Autobiography''; Upson Clark. Rakovsky was expelled from the gymnasium in Gabrovo

Gabrovo ( ) is a city in central northern Bulgaria, the Local government, administrative centre of Gabrovo Province.It is situated at the foot of the central Balkan Mountains, in the valley of the Yantra River, and is known as an international ca ...

for his political activities (in 1887 and then again, after organizing a riot, in 1890). It was around that time that he became a Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

, and began collaborating with the socialist journalist Evtim Dabev, whom he aided in printing works by Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Rakovsky, "An Autobiography". Since, after having ultimately been banned from attending any public school in the country, he could not complete his education in Bulgaria, in September 1890, Rakovsky went to

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Rakovsky, "An Autobiography". Since, after having ultimately been banned from attending any public school in the country, he could not complete his education in Bulgaria, in September 1890, Rakovsky went to

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

to begin his studies and become a physician. While in Switzerland, he joined the Socialist Student Circle at the University of Geneva

The University of Geneva (French: ''Université de Genève'') is a public university, public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded in 1559 by French theologian John Calvin as a Theology, theological seminary. It rema ...

, which was largely composed of non-Swiss youth.

A polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. When the languages are just two, it is usually called bilingualism. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolin ...

,Anghel & Iosif, pg. 257; Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''. Rakovsky became close to Georgy Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism, and his circle, eventually writing a number of articles and a book in Russian. He briefly worked with Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg ( ; ; ; born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. She was a key figure of the socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 20t ...

, Pavel Axelrod, and Vera Zasulich

Vera Ivanovna Zasulich (; – 8 May 1919) was a Russian socialist activist, Menshevik writer and revolutionary. She is widely known for her correspondence with Karl Marx, in which she put into question the necessity of a capitalist industriali ...

. Unable to attend the First International Congress of Socialist Students in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

(1892), he became involved in organizing the Second Congress, held in Geneva during the fall of 1893.

He was a founding editor of the Geneva-based Bulgarian-language magazine ''Sotsial-Demokrat'' and later a major contributor to the Bulgarian Marxist publications ''Den, ''Rabotnik'', and ''Drugar''. At the time, Rakovsky and Balabanov, with Plekhanov's encouragement, stressed the importance for moderation in socialist policies—''Sotsial-Demokrat'' rallied with the Bulgarian Social Democratic Union and rejected the more radical Bulgarian Social Democratic Party

The Bulgarian Social Democratic Party (, ''Balgarska Sotsialdemokraticheska Partiya'', BSDP) is a social-democratic political party in Bulgaria.

History

The party was launched on 26 November 1989 under the name Bulgarian Social Democratic Work ...

. He soon became involved in distributing socialist propaganda inside Bulgaria, at a time when Stefan Stambolov

Stefan Nikolov Stambolov (; 31 January 1854 Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in Eastern Europe, OS – 19 July 1895 Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in Eastern Europe, OS) was a Bulgarian politician, journalist, revoluti ...

organized a crackdown on political opposition.

Later in 1893, Rakovsky enrolled in a medical school in Berlin, contributing articles for '' Vorwärts'' and becoming close to Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht (; 29 March 1826 – 7 August 1900) was a German socialist activist and politician. He was one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). As a Bulgarian delegate to the

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the  Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in

Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in

In April–May 1918, he negotiated with the Tsentral'na Rada of the

In April–May 1918, he negotiated with the Tsentral'na Rada of the

''Russia in 1919''

Retrieved 19 July 2007. While in office, Rakovsky ignored the Ukrainian "national question" because of his view on the nationalist movements as a counter-revolutionary force, as Rakovsky believed that national issues were important during the bourgeois era, but that they would lose its importance during the emerging world revolution. He seemed unaware of the dangers of Russian nationalism and chauvinism and claimed that the "danger of Russification under the existing Ukrainian Soviet authority is entirely without foundation", although he changed his stance in the early 1920sFagan,

'. At the time, Rakovsky assessed the situation created by the Treaty of Versailles, and advised his superiors to build warm relations with both Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Mustafa Kemal's Turkey and the Weimar Republic, as a camp of countries dissatisfied with policies of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers.Fagan, ''Soviet Diplomat (1923–27)'' Rakovsky subscribed to the Bolshevik condemnation of Greater Romania, stance that journalist Victor Frunză considered a revision of his previous views on Bessarabia. During the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Paris Peace Conference, the Romanian delegation attributed the shortage in supply in Bessarabia and Transylvania a Bolshevik Conspiracy (political), conspiracy centered on Rakovsky;Livezeanu, pg. 250 various French reports of the time gave contradictory assessments (while some credited Rakovsky with direct influence on Soviet foreign policy, others dismissed the notion that Russia had any such projects). Rakovsky simultaneously served as Soviet Ukraine's Commissar for Foreign Affairs and a member of the South West Front's Revolutionary Military Council, contributing to the defeat of the White movement, White Army and Ukrainian nationalists during the Russian Civil War, while theorizing that "Ukraine was a laboratory of Proletarian internationalism, internationalism" and "a decisive factor in world revolution".Rakovsky, in Fagan, ''Rakovsky and the Ukraine (1919–23)''. Rakovsky's presence was also decisive in rallying the dissident Borotbists to the Bolshevik faction's central bodies—he was subsequently confronted with a degree of Borotbist opposition inside his government. According to American politologist Jerry F. Hough, his appointment and policies were evidence of Russification, a program requested by Lenin himself; Rakovsky's view contrasted with that supported by Stalin, who, at the time, was calling for increased Ukrainianization.Jerry F. Hough, ''Democratization and Revolution in the USSR, 1985–1991'', Brookings Institution, Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C. (1997), pp. 223-224;

On 13 February 1919, in a session of Kyiv City Council, and later in March of 1919, during the Third All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets, Rakovsky as a head of Ukrainian government stated that "decreeing the Ukrainian language as a state language is reactionary and unnecessary", as there is no need to declare state languages in Soviet republics; according to him, all languages are equal in Soviet Ukraine, and "no decrees are needed to make the language spoken by the vast majority of the population the ''de facto'' dominant language... I must state to you that we had to issue a reprimand to the Commissar of Posts and Telegraphs, who... issued an order that political affairs at the Post and the Telegraph should be conducted exclusively in the Russian language."

In March 1919, Rakovsky was a founding member of the

Rakovsky simultaneously served as Soviet Ukraine's Commissar for Foreign Affairs and a member of the South West Front's Revolutionary Military Council, contributing to the defeat of the White movement, White Army and Ukrainian nationalists during the Russian Civil War, while theorizing that "Ukraine was a laboratory of Proletarian internationalism, internationalism" and "a decisive factor in world revolution".Rakovsky, in Fagan, ''Rakovsky and the Ukraine (1919–23)''. Rakovsky's presence was also decisive in rallying the dissident Borotbists to the Bolshevik faction's central bodies—he was subsequently confronted with a degree of Borotbist opposition inside his government. According to American politologist Jerry F. Hough, his appointment and policies were evidence of Russification, a program requested by Lenin himself; Rakovsky's view contrasted with that supported by Stalin, who, at the time, was calling for increased Ukrainianization.Jerry F. Hough, ''Democratization and Revolution in the USSR, 1985–1991'', Brookings Institution, Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C. (1997), pp. 223-224;

On 13 February 1919, in a session of Kyiv City Council, and later in March of 1919, during the Third All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets, Rakovsky as a head of Ukrainian government stated that "decreeing the Ukrainian language as a state language is reactionary and unnecessary", as there is no need to declare state languages in Soviet republics; according to him, all languages are equal in Soviet Ukraine, and "no decrees are needed to make the language spoken by the vast majority of the population the ''de facto'' dominant language... I must state to you that we had to issue a reprimand to the Commissar of Posts and Telegraphs, who... issued an order that political affairs at the Post and the Telegraph should be conducted exclusively in the Russian language."

In March 1919, Rakovsky was a founding member of the

In February 1922, he was sent to Berlin in order to negotiate with German officials, and, in March, was part of the official delegation to the Genoa Conference — under the leadership of Georgy Chicherin. Rakovsky himself was virulently opposed to any stalemate with the Allies of World War I, Allies, and urged his delegation not to abandon policies over promises of deescalation and trade. A leader of the delegation's commissions on economic aid, loans and government debt, he was also charged with renewing contacts with Germany — together with

In February 1922, he was sent to Berlin in order to negotiate with German officials, and, in March, was part of the official delegation to the Genoa Conference — under the leadership of Georgy Chicherin. Rakovsky himself was virulently opposed to any stalemate with the Allies of World War I, Allies, and urged his delegation not to abandon policies over promises of deescalation and trade. A leader of the delegation's commissions on economic aid, loans and government debt, he was also charged with renewing contacts with Germany — together with

In parallel, he had begun negotiations with France's Raymond Poincaré, who aimed for a "solidarity of foreign creditors" in respect to the Soviet state, and who agreed to recognize the latter on October 28, 1924. One of his last tasks involved placing Soviet orders for machinery, textiles, and other commodities with British manufacturers: worth 75 million US$ on paper, these failed to attract attention after he announced that the Soviet government did not intend to pay in cash. According to the American magazine ''Time'', Rakovsky also played a hand in motivating Stalin's decision to marginalize Comintern leader Zinoviev, by complaining that the latter's foreign policy was needlessly radical.

Rakovsky served as the List of Ambassadors of Russia to France, Soviet ambassador to France between October 1925 and October 1927, replacing Leonid Krasin. He did not take hold of his office until 50 days after his official appointment, refusing to be received at the Élysée Palace by President of France, French President Gaston Doumergue for as long as the state authorities would not allow ''The Internationale'' (a revolutionary song which was at the time the Soviet national anthem) to be played on the occasion."Bugle Blast", in ''Time'', December 21, 1925 Doumergeue resisted, and, in the end, Rakovsky was received to the sound of an improvised arrangement of Bugle (instrument), bugles, the more discreet part of which may have been based on ''The Internationale''. ''Time'' described it as a "deafening blast".

His first task involved renewed negotiations with the cabinet of Aristide Briand (February 1926), during which he was confronted with the vocal campaign of creditors. Early results achieved in discussions with Anatole de Monzie were dismissed by the opposition rallied around Poincaré, and, after being revived by the short-lived cabinet of Édouard Herriot, talks ended without any result. Poincaré returned to power, and France remained committed to the Locarno Treaties (which had isolated the Soviet state on the international stage). Over the following year, Rakovsky continued to attempt a ''détente'' with France, advertising Soviet concessions and speaking directly to the public.

During the same period, as tensions grew between Mexico and the Soviet government over the latter's support for a Mexican railway workers' strike, American agents reported that Rakovsky was instructed to threaten to publicize correspondence between former President of Mexico, President Álvaro Obregón and Soviet authorities (which had occurred before diplomatic links were established).Daniela Spenser, ''Impossible Triangle: Mexico, Soviet Russia, and the United States in the 1920s'', Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, Durham, 1999, p.105-106. Since this could endanger Mexico's relations with the United States, President Plutarco Elías Calles chose to deescalate the conflict.

Together with his second wife, Rakovsky gave full approval to Max Eastman's volume ''Since Lenin Died'', which centered on heavy criticism of Soviet realities, and which they reviewed before it was published. He became acquainted with the former French Communist Party member and anti-Stalinism, Stalinist journalist Boris Souvarine, as well as with the Romanian writer Panait Istrati, who had observed Rakovsky's career ever since his presence in Romania.Tănase, "The Renegade Istrati" He also maintained friendly contacts with Marcel Pauker, a prominent but independent-minded member of the Romanian Communist Party, whose activities were denounced by the Comintern in 1930.Robert Levy, ''Ana Pauker: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Communist'', University of California Press, Berkeley, California, Berkeley, 2001, p.64-66.

Rakovsky was eventually declared a ''persona non grata'' in France and recalled after signing the ''Declaration of the Opposition'', a

In parallel, he had begun negotiations with France's Raymond Poincaré, who aimed for a "solidarity of foreign creditors" in respect to the Soviet state, and who agreed to recognize the latter on October 28, 1924. One of his last tasks involved placing Soviet orders for machinery, textiles, and other commodities with British manufacturers: worth 75 million US$ on paper, these failed to attract attention after he announced that the Soviet government did not intend to pay in cash. According to the American magazine ''Time'', Rakovsky also played a hand in motivating Stalin's decision to marginalize Comintern leader Zinoviev, by complaining that the latter's foreign policy was needlessly radical.

Rakovsky served as the List of Ambassadors of Russia to France, Soviet ambassador to France between October 1925 and October 1927, replacing Leonid Krasin. He did not take hold of his office until 50 days after his official appointment, refusing to be received at the Élysée Palace by President of France, French President Gaston Doumergue for as long as the state authorities would not allow ''The Internationale'' (a revolutionary song which was at the time the Soviet national anthem) to be played on the occasion."Bugle Blast", in ''Time'', December 21, 1925 Doumergeue resisted, and, in the end, Rakovsky was received to the sound of an improvised arrangement of Bugle (instrument), bugles, the more discreet part of which may have been based on ''The Internationale''. ''Time'' described it as a "deafening blast".

His first task involved renewed negotiations with the cabinet of Aristide Briand (February 1926), during which he was confronted with the vocal campaign of creditors. Early results achieved in discussions with Anatole de Monzie were dismissed by the opposition rallied around Poincaré, and, after being revived by the short-lived cabinet of Édouard Herriot, talks ended without any result. Poincaré returned to power, and France remained committed to the Locarno Treaties (which had isolated the Soviet state on the international stage). Over the following year, Rakovsky continued to attempt a ''détente'' with France, advertising Soviet concessions and speaking directly to the public.

During the same period, as tensions grew between Mexico and the Soviet government over the latter's support for a Mexican railway workers' strike, American agents reported that Rakovsky was instructed to threaten to publicize correspondence between former President of Mexico, President Álvaro Obregón and Soviet authorities (which had occurred before diplomatic links were established).Daniela Spenser, ''Impossible Triangle: Mexico, Soviet Russia, and the United States in the 1920s'', Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, Durham, 1999, p.105-106. Since this could endanger Mexico's relations with the United States, President Plutarco Elías Calles chose to deescalate the conflict.

Together with his second wife, Rakovsky gave full approval to Max Eastman's volume ''Since Lenin Died'', which centered on heavy criticism of Soviet realities, and which they reviewed before it was published. He became acquainted with the former French Communist Party member and anti-Stalinism, Stalinist journalist Boris Souvarine, as well as with the Romanian writer Panait Istrati, who had observed Rakovsky's career ever since his presence in Romania.Tănase, "The Renegade Istrati" He also maintained friendly contacts with Marcel Pauker, a prominent but independent-minded member of the Romanian Communist Party, whose activities were denounced by the Comintern in 1930.Robert Levy, ''Ana Pauker: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Communist'', University of California Press, Berkeley, California, Berkeley, 2001, p.64-66.

Rakovsky was eventually declared a ''persona non grata'' in France and recalled after signing the ''Declaration of the Opposition'', a

After that moment, although branded "enemy of the people", Rakovsky was still occasionally allowed to speak in public (notably, together with Kamenev and

After that moment, although branded "enemy of the people", Rakovsky was still occasionally allowed to speak in public (notably, together with Kamenev and

Christian Rakovsky Internet Archive

at Marxists.org: ** Gus Fagan

Biographical Introduction to Christian Rakovsky, ''Selected Writings on Opposition in the USSR 1923–30'' (editor: Gus Fagan), Allison & Busby, London & New York, 1980

retrieved July 19, 2007 ** Christian Rakovsky

translated by Gus Fagan; retrieved July 19, 2007 *

''110 ani de social-democraţie în România'' ("110 Years of Social Democracy in Romania")

Social Democratic Party (Romania), Social Democratic Party, Ovidiu Şincai Social Democratic Institute,

''Arbitrary Justice: Courts and Politics in Post-Stalin Russia''

National Council for Soviet and East European Research and Lehigh University, Washington, D. C., 1995; retrieved July 19, 2007 * Victor Frunză, ''Istoria stalinismului în România'' ("The History of Stalinism in Romania"), Humanitas, Bucharest, 1990. * Ștefan Octavian Iosif, Șt. O. Iosif, Dimitrie Anghel, D. Anghel, "Racovski", in ''Cireşul lui Lucullus. Teatru, proză, traduceri'' ("Lucullus' Cherry Tree. Drama, Prose, Translations"), Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1976. * Irina Livezeanu, ''Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building and Ethnic Struggle, 1918–1930'', Cornell University Press, New York City, 1995. * Roy Medvedev, ''Let History Judge'', Spokesman Books, Nottingham, 1976. * Z. Ornea, ''Viaţa lui C. Stere'' ("The Life of C. Stere"), Vol. I, Cartea Românească, Bucharest, 1989. * Christian Rakovsky

''Les socialistes et la guerre'' ("The Socialists and the War"), 1915

at Marxists.org (French edition); retrieved July 19, 2007 * Judith Shapiro

in ''Revolutionary History'', Vol. 2, No. 2, Summer 1989; retrieved July 19, 2007 * Stelian Tănase, **

"Cristian Racovski" (Part I)

in ''Magazin Istoric'', April 2004; retrieved July 19, 2007 *

"The Renegade Istrati", excerpt from ''Auntie Varvara's Clients''

translated by Alistair Ian Blyth, in ''Archipelago'', Vol.10–12; retrieved July 19, 2007 * Vladimir Tismăneanu, ''Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism'', University of California Press, Berkeley, California, Berkeley, 2003, * Glenn E. Torrey, "Rumania's Decision to Intervene: Brătianu and the Entente, June–July 1916", in Keith Hitchins (ed.), ''Romanian Studies. Vol. 2, 1971–1972'', Brill Publishers, Leiden, 1973, p. 3–29. *

''Christian Rakovsky et Basile Kolarov'' ("Christian Rakovsky and Vasil Kolarov"), 1915

at Marxists.org (French edition); retrieved July 19, 2007 * Charles Upson Clark

''Bessarabia. Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea'': Chapter XXI, "Rakovsky's Roumanian Career"

at the University of Washington; retrieved July 19, 2007

Trotsky's unfinished biography of Rakovsky

*

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rakovsky, Christian 1873 births 1941 deaths Members of the Orgburo of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 9th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) People from Kotel, Bulgaria Bulgarian expatriates in Ukraine Bulgarian activists Bulgarian communists Bulgarian journalists Bulgarian people of World War I Romanian Marxist journalists Romanian activist journalists Romanian Trotskyists Romanian escapees Romanian Land Forces officers Romanian magazine editors Romanian newspaper editors Romanian people of World War I Romanian military doctors Romanian political candidates People deported from Romania Escapees from Romanian detention Marxist journalists Social Democratic Party of Romania (1910–1918) politicians Leaders of political parties in Romania Anti–World War I activists People of the Russian Revolution Romanian Comintern people Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) politicians Politicians from the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to France Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to the United Kingdom Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Japan Romanian people of Bulgarian descent Romanian writers in French Bulgarian expatriates in Romania Bulgarian Comintern people Great Purge victims Case of the Anti-Soviet "Bloc of Rightists and Trotskyites" Bulgarian people imprisoned abroad Bulgarian people executed by the Soviet Union Executed Soviet people Soviet civilians killed in World War II Deaths by firearm in the Soviet Union Soviet rehabilitations Soviet show trials Executed Bulgarian people Ukrainian diplomats Chairpersons of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine Left Opposition Old Bolsheviks Soviet interior ministers of Ukraine Soviet foreign ministers of Ukraine Marxian economists Executed communists Immigrants to the Russian Empire People from the Principality of Bulgaria Health professionals killed in wars Politicians killed in World War II Anti-nationalists

Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

Congress in Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

, he also met with Engels and Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

.

Six months later, he was arrested and expelled from the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

for maintaining close contacts with the Russian revolutionaries there. He finished his education in 1894–1896 in Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

, Nancy and Montpellier

Montpellier (; ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the Departments of France, department of ...

, where he wrote for '' La Jeunesse Socialiste'' and '' La Petite République'', maintaining a friendship with Guesde and becoming an opponent of Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; ), was a French socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became a social democrat and one of the first possibi ...

' reformist

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

views.

According to his own testimony, he became active in supporting the Anti-Ottoman upsurge in Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

and Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, as well as Dashnak revolutionary activities. In 1896, he was the Bulgarian representative to the Second International's London Congress (part of his speech was published in Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian Marxism, Marxist theorist. A leading theorist of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Second International, Kautsky advocated orthodox Marxism, a ...

's ''Die Neue Zeit

''Die Neue Zeit'' ("The New Times") was a German socialist theoretical journal of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) that was published from 1883 to 1923. Its headquarters was in Stuttgart, Germany.

History and profile

Founded by lead ...

'').

Military service and first stay in Russia

Although actively involved in many European countries' socialist movements, prior to 1917 Rakovsky's focus remained on the Balkans and especially on his native country and Romania; his activities in support of the international socialist movement led to his expulsion, at different times, from Germany, Bulgaria, Romania, France and Russia. In 1897, he published ''Russiya na Istok'' (''Russia in the East''), a book sharply critical of theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

's foreign policy, which, according to Rakovsky, followed one of Georgy Plekhanov's guidelines ("Tsarist Russia must be isolated in its foreign relations"). On several occasions, he publicly criticized Russia's policies towards Romania and in Bessarabia

Bessarabia () is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Bessarabia lies within modern-day Moldova, with the Budjak region covering the southern coa ...

(describing Russia's rule over the latter as " absolutist conquest", "mischievous action", and "abduction"). According to Rakovsky, " Russophile papers" in Bulgaria had begun to target him as a consequence.

After completing his education as a physician at the University of Montpellier

The University of Montpellier () is a public university, public research university located in Montpellier, in south-east of France. Established in 1220, the University of Montpellier is one of the List of oldest universities in continuous opera ...

Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Tănase, "Cristian Racovski". (with the thesis ''L'Éthiologie du crime et de la dégénérescence'' – "The Cause of Crime and Degeneration", submitted in 1897),Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Upson Clark Rakovsky, who had married the Russian student E. P. Ryabova, was summoned to Romania in order to be drafted in the Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces () is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. Since 2007, full professionalization and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Land Forces.

The Romanian Land Forc ...

, and served as a medic

A medic is a person trained to provide medical care, encompassing a wide range of individuals involved in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of health conditions. The term can refer to fully qualified medical practitioners, such as physic ...

in the 9th Cavalry Regiment stationed in Constanţa, Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; or ''Dobrudža''; , or ; ; Dobrujan Tatar: ''Tomrîğa''; Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and ) is a Geography, geographical and historical region in Southeastern Europe that has been divided since the 19th century betw ...

(1899–1900). He rose to the rank of lieutenant.Upson Clark

Rakovsky subsequently rejoined his wife in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, where he hoped to settle down and engage in revolutionary activities (he was probably expelled after an initial attempt to enter the country, but was allowed to return). An adversary of Peter Berngardovich Struve after the latter moved towards market liberalism, he became acquainted with, among others, Nikolay Mikhaylovsky

Nikolay Konstantinovich Mikhaylovsky (; – ) was a Russian literary critic, sociologist, writer on public affairs, and one of the theoreticians of the Narodniki movement.

Biography

The school of thinkers he belonged to became famous in the ...

and Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky

Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky (; ; January 20, 1865 - January 21, 1919) was a Russian and Ukrainian Marxism, Marxist, economist, and politician.

He was a leading exponent of Legal Marxism in the Russian Empire and was the author of numerous works dea ...

, while authoring articles for '' Nashe Slovo'' and helping distribute ''Iskra

''Iskra'' (, , ''the Spark'') was a fortnightly political newspaper of Russian socialist emigrants established as the official organ of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

History

''Iskra'' was published in exile and then smuggl ...

''. His close relationship with Plekhanov led Rakovsky to a position between the Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

and Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

, one he kept from 1903 to 1917; the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

was initially hostile to Rakovsky, and at one point wrote to Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a revolutionary and writer active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a Communist International leader in the Soviet Union after the Russian ...

that "we he Bolsheviksdo not have the same road as his kind of people".

Initially, Rakovsky was expelled from Russia and had to move back to Paris. Returning to the Russian capital in 1900, he remained there until 1902, when his wife's death and the crackdown on socialist groups ordered by Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

Nicholas II forced him to return to France. Working for a while as a physician in the village of Beaulieu, Haute-Loire, he asked French officials to review his case for naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

, but was refused.

In 1903, following the death of his father, Rakovsky again lived in Paris, where he followed developments of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

and spoke out against Russia, attracting, according to Rakovsky himself, the criticism of both Plekhanov and Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

. He voiced his opposition to the concession made by Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian Marxism, Marxist theorist. A leading theorist of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Second International, Kautsky advocated orthodox Marxism, a ...

to Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; ), was a French socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became a social democrat and one of the first possibi ...

, one which had allowed socialists to join "bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

" governments in times of crisis.Rakovsky, ''Les socialistes et la guerre''.

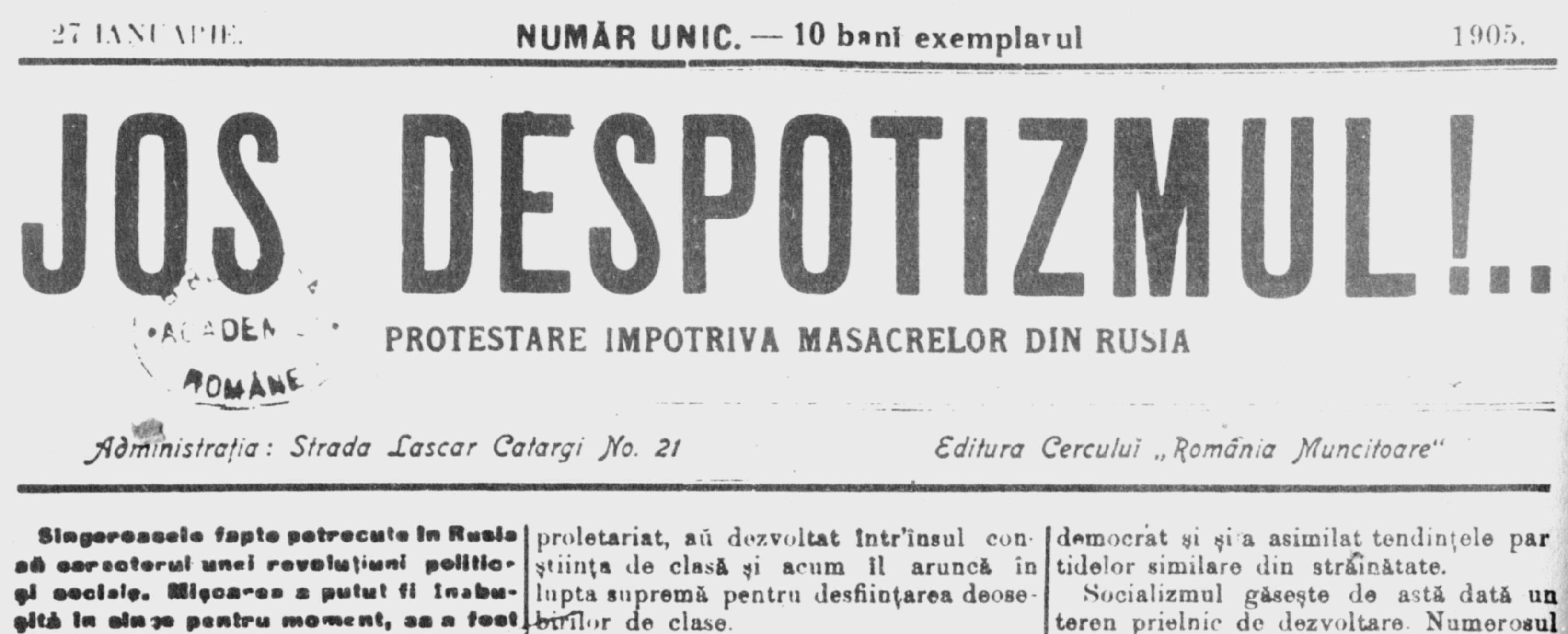

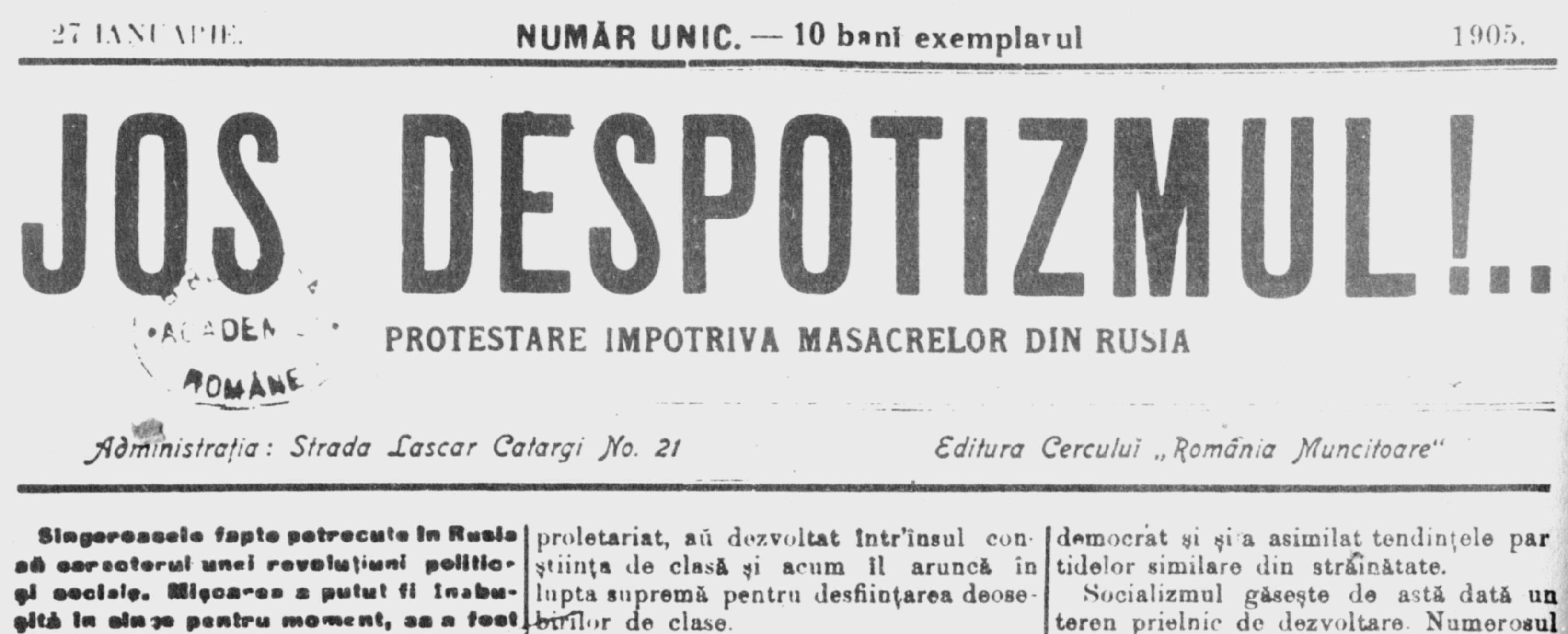

''România Muncitoare''

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near Mangalia

Mangalia (, ), ancient Callatis (; other historical names: Pangalia, Panglicara, Tomisovara), is a city and a port on the coast of the Black Sea in the south-east of Constanța County, Northern Dobruja, Romania.

The municipality of Mangalia als ...

. In 1913, his property, valued at some 40,000 United States dollars at the time, was home to Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

when the latter visited the Balkans as a press envoy during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

. He was usually present in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

on a weekly basis, and started an intense activity as a journalist, doctor and lawyer. The Balkans correspondent for ''L'Humanité

(; ) is a French daily newspaper. It was previously an organisation of the SFIO, ''de facto'', and thereafter of the French Communist Party (PCF), and maintains links to the party. Its slogan is "In an ideal world, would not exist."

History ...

'', he was also personally responsible for reviving '' România Muncitoare'', the defunct journal of the Romanian socialist group, provoking successful strike actions which brought him to the attention of officials.

Christian Rakovsky also traveled to Bulgaria, where he eventually sided with the '' Tesnyatsi'' in their conflict with other socialist groups. In 1904, he was present at the Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

's Congress in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

, where he gave a speech celebrating the assassination of Russian police chief Vyacheslav von Plehve by Socialist-Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR; ,, ) was a major socialist political party in the late Russian Empire, during both phases of the Russian Revolution, and in early Soviet Russia. The party members were known as Esers ().

The SRs were ag ...

members.

Rakovsky became noted locally especially after 1905, when he organized rallies in support of the Battleship Potemkin revolt (the events worsened relations between Russia and the Romanian Kingdom), carried out a relief operation for the ''Potemkin'' crew as their ship sought refuge in Constanţa, and attempted to persuade them to set sail for Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ), historically Batum or Batoum, is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second-largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast ...

and aid striking workers there. According to his own account, a parallel scandal occurred when an armed Bolshevik ship was captured in Romanian territorial waters; Rakovsky, who indicated that the weapons on board were to be used in Batumi, faced allegations in the Romanian press that he was preparing a Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; or ''Dobrudža''; , or ; ; Dobrujan Tatar: ''Tomrîğa''; Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and ) is a Geography, geographical and historical region in Southeastern Europe that has been divided since the 19th century betw ...

n insurrection.

His head was injured during street clashes with police forces

The police are a constituted body of people empowered by a state with the aim of enforcing the law and protecting the public order as well as the public itself. This commonly includes ensuring the safety, health, and possessions of citize ...

over the ''Potemkin'' issue; while recovering, Rakovsky befriended the Romanian poets Ștefan Octavian Iosif

Ștefan Octavian Iosif (; 11 October 1875 – 22 June 1913) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian poet and translator.

Life

Born in Brașov, Transylvania (part of Austria-Hungary at the time), he studied in his native town and in Sibiu befor ...

and Dimitrie Anghel, who were publishing works under a common signature—one of the two authored a sympathetic portrait of the socialist leader, based on his recollections from the early 1900s. Throughout these years, Rakovsky, was, according to Iosif and Anghel, "continuously bustling; disappearing and appearing in workers' centers, be it in Brăila

Brăila (, also , ) is a city in Muntenia, eastern Romania, a port on the Danube and the capital of Brăila County. The Sud-Est (development region), ''Sud-Est'' Regional Development Agency is located in Brăila.

According to the 2021 Romanian ...

, be it in Galaţi, be it in Iaşi, be it anywhere, always preaching with the same undaunted fervor and fanatical conviction his social credo".

Rakovsky was drawn into a polemic with the Romanian authorities, facing public accusations that, as a Bulgarian, he lacked patriotism. In return, he commented that, if patriotism meant " race prejudice, international and civil war, political tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English language, English usage of the word, is an autocracy, absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurper, usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defen ...

and plutocratic domination", he refused to be identified with it. Upon the outbreak of Romanian Peasants' Revolt of 1907, Rakovsky was especially vocal: he launched accusations at the National Liberal government, arguing that, having profited from the early antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

message of the revolt, it had violently repressed it from the moment peasants began to attack landowners. Supportive of the thesis according to which the peasantry had revolutionary importance inside Romanian society and Eastern Europe at large, Rakovsky publicized his perspective in the socialist press (writing articles on the subject for ''România Muncitoare'', ''L'Humanité'', ''Avanti!

''Avanti!'' (; Italian interjection – 'come in!') is a 1972 comedy film produced and directed by Billy Wilder, and starring Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills. The screenplay by Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond is based on Samuel A. Taylor's pla ...

'', '' Vorwärts'' and others).

Rakovsky was also one of the journalists suspected of having greatly exaggerated the overall death toll in their accounts: his estimates speak of over 10,000 peasants killed, whereas the government data counted only 421.

He became close to the influential dramatist Ion Luca Caragiale

Ion Luca Caragiale (; According to his birth certificate, published and discussed by Constantin Popescu-Cadem in ''Manuscriptum'', Vol. VIII, Nr. 2, 1977, pp. 179–184 – 9 June 1912), commonly referred to as I. L. Caragiale, was a Romanians, ...

, who was living in Berlin at the time. Caragiale authored his own virulent critique of the Romanian state and its handling of the revolt, an essay titled ''1907, din primăvară până în toamnă'' ("1907, From Spring to Autumn"), which, in its final version, adopted some of Rakovsky's suggestions.

1907 expulsion

After repeatedly condemning repression of the revolt, Rakovsky was, together with other socialists, officially accused of having agitated rebellious sentiment, and consequently expelled from Romanian soil (late 1907). He received news of this action while already abroad, inStuttgart

Stuttgart (; ; Swabian German, Swabian: ; Alemannic German, Alemannic: ; Italian language, Italian: ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, largest city of the States of Germany, German state of ...

(at the Seventh Congress of the Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

). He decided not to recognize it, and contended that his father had settled in Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

before the Treaty of Berlin that had awarded the region to Romania; the plea was rejected by the Court of Appeal

An appellate court, commonly called a court of appeal(s), appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to Hearing (law), hear a Legal case, case upon appeal from a trial court or other ...

, based on evidence that Rakovsky's father was not in Dobruja before 1880, and that Rakovsky himself used a Bulgarian passport when moving across borders. During the 1920s, Rakovsky was still viewing the incident as a "blatantly illegal act".

The action itself caused protests from leftist politicians and sympathizers, including, among others, the influential Marxist thinker Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea (born Solomon Katz; 21 May 1855 – 7 May 1920) was a Romanian Marxist theorist, politician, sociologist, literary critic, and journalist. He was also an entrepreneur in the city of Ploiești. Constantin Dobroge ...

(whose appeal in favor of Rakovsky was described by Iosif and Anghel as evidence of "an almost parental love"). The local socialists organized several rallies in his support, and the return of his citizenship was also backed by Take Ionescu

Take or Tache Ionescu (; born Dumitru Ghiță Ioan and also known as Demetriu G. Ionnescu; – 21 June 1922) was a Romanian Centrism, centrist politician, journalist, lawyer and diplomat, who also enjoyed reputation as a short story author. Sta ...

's opposition group, the Conservative-Democratic Party

The Conservative-Democratic Party (, PCD) was a political party in Romania. Over the years, it had the following names: the Democratic Party, the Nationalist Conservative Party, or the Unionist Conservative Party.

The Conservative-Democratic Part ...

. In exile, Rakovsky authored the pamphlet ''Les persécutions politiques en Roumanie'' ("Political Persecutions in Romania") and two books (''La Roumanie des boyars'' – "Boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

Romania", and the since-lost ''From the Kingdom of Arbitrariness and Cowardice'').

Eventually, he traveled back into Romania in October 1909, only to be arrested upon his transit through Brăila County

Brăila County () is a county (județ) of Romania, in Muntenia, with the capital city at Brăila.

Demographics

At the 2021 Romanian census, Brăila County had a population of 281,452 (172,533 people in urban areas and 108,919 people in rural ...

.

According to his recollections, he was for long left stranded on the border with Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, as officials in the latter country refused to let him pass; the situation had to be settled by negotiations between the two countries. Also according to Rakovsky, the arrest was hidden by the Ion I. C. Brătianu cabinet until it leaked to the press — this, coupled with rumors that he was about to be killed, and Brătianu's statement that he would "rather destroy akovskythan let imback into Rumania", caused a series of important street clashes between his supporters and government forces. On 9 December 1909, a Romanian Railways employee named Stoenescu attempted to assassinate Brătianu. The event, which was attributed by Rakovsky to support for his return and by other sources to government manipulation,Ornea, pp. 521-522 caused a clampdown on '' România Muncitoare'' (among those socialists arrested and interrogated were Gheorghe Cristescu, I. C. Frimu, and Dumitru Marinescu).

Rakovsky secretly returned to Romania in 1911, giving himself up in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

. According to Rakovsky, he was again expelled, holding a Romanian passport, to Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

, where he was swiftly arrested by the Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

government but released soon after. He subsequently left for Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

, where he established the Bulgarian socialist journal '' Napred''. Ultimately, the new Petre P. Carp Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

cabinet agreed to allow his return to Romania, following pressures from the French Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of govern ...

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

(who answered an appeal by Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; ), was a French socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became a social democrat and one of the first possibi ...

). According to Rakovsky, this was also determined by the Conservative change in policies towards the peasantry. He unsuccessfully ran for Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

during the elections of that year (and several others in succession), being fully reinstated as a citizen in April 1912. Romanian journalist Stelian Tănase contends that the expulsion had instilled resentment in Rakovsky;Tănase, "Cristian Racovski" earlier, the leading National Liberal politician Ion G. Duca himself had argued that Rakovsky was developing a "hatred for Romania".

PSDR and Zimmerwald Movement

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

; notably, Rakovsky expressed criticism of Romania's invasion of Bulgaria during the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia and Kingdom of Greece, Greece, on 1 ...

, and called on Romanian authorities not to annex Southern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja or South Dobruja ( or simply , ; or , ), also the Quadrilateral (), is an area of north-eastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silistra provinces, part of the historical region of Dobruja. It has an area of 7,412 square km an ...

. Alongside Frimu, Bujor, Ecaterina Arbore and others, he lectured at the PSDR's propaganda school during the short period the latter was in existence (in 1910 and again in 1912–1913).

In 1913, Rakovsky was married a second time, to Alexandrina Alexandrescu (also known as Ileana Pralea), a socialist militant and intellectual, who taught mathematics in Ploieşti.Brătescu, pg. 425 Alexandrescu was herself a friend of Dobrogeanu-Gherea and an acquaintance of Caragiale. She had previously been married to Filip Codreanu, a Narodnik

The Narodniks were members of a movement of the Russian Empire intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, Narodnism or ,; , similar to the ...

activist born in Bessarabia, with whom she had a daughter, Elena, and a son, Radu.

Rallying with the left wing of international social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

during the early stages of World War I, Rakovsky later indicated that he had been purposely informed of the controversial pro-war stance taken by the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany ( , SPD ) is a social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany. Saskia Esken has been the party's leader since the 2019 leadership election together w ...

by the pro- Entente Romanian Foreign Minister Emanoil Porumbaru.Fagan, ''Regroupment of the socialist movement'' With staff of the Menshevik paper '' Nashe Slovo'' (edited by Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

), he was among the most prominent socialist pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

of the period. Reflecting his ideological priorities, '' România Muncitoares title was changed into ''Jos Răsboiul!'' ("Down with war!")—it was later to be known as ''Lupta Zilnică'' (the "Daily combat").

Heavily critical of the French Socialist Party

The Socialist Party ( , PS) is a Centre-left politics, centre-left to Left-wing politics, left-wing List of political parties in France, political party in France. It holds Social democracy, social democratic and Pro-Europeanism, pro-European v ...

's decision to join the René Viviani cabinet (deeming it "an abdication"), he stressed the responsibility of all European countries in provoking the war, and adhered to Trotsky's vision of a "Peace without indemnities or annexations" as an alternative to "imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

war". According to Rakovsky, tensions between the French SFIO and the German Social Democrats were reflecting not just context, but major ideological differences.

Present in Italy in March 1915, he attended the Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

Congress of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

, during which he attempted to persuade it to condemn irredentist goals.Rakovsky, "An Autobiography"; Tănase, "Cristian Racovski". In July, after convening the Bucharest Conference, he and Vasil Kolarov

Vasil Petrov Kolarov (; 16 July 1877 – 23 January 1950) was a Bulgarian communist political leader and leading functionary in the Communist International (Comintern).

Biography Early years

Kolarov was born in Şumnu, Ottoman Empire (now Shum ...

established the Revolutionary Balkan Social Democratic Labor Federation (comprising the left-leaning socialist parties of Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and Greece), and Rakovsky was elected first secretary of its Central Bureau.

Subsequently, together with the Italian Socialist delegates ( Oddino Morgari, Giacinto Menotti Serrati

Giacinto Menotti Serrati (; 25 November 1872 – 10 May 1926) was an Italian communist politician and newspaper editor.

Biography

He was born in Spotorno. He was a central leader of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), editor of the paper ''Avant ...

, and Angelica Balabanoff among them), Rakovsky was instrumental in convening the anti-war international socialist Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915. During the congress, he came into open conflict with Lenin, after the latter voiced the Zimmerwald Left's opposition to the resolution (at one point, Rakovsky reportedly lost his temper and grabbed Lenin, causing him to temporarily leave the hall in protest). Later, he continued to mediate between Lenin and the Second International, a situation from which emerged a circular letter that complemented the ''Zimmerwald Manifesto'' while being more radical in tone. In October 1915, he reportedly did not protest Bulgaria's entry into the war — this information was contradicted by Trotsky, who also indicated that the '' Tesniatsy'' had been the target of a government crackdown at that exact moment.

Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in

Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in Covurlui County

Covurlui County is one of the historic counties of Moldavia, Romania. The county seat was Galați.

In 1938, the county was disestablished and incorporated into the newly formed Ținutul Dunării, but it was re-established in 1940 after the fall of ...

. Again arrested in 1916, after being accused of planning rebellion during a violent incident in Galaţi, he was, according to his own account, freed by a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...