Christian Nonresistance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian pacifism is the

Christian pacifism is the

Roots of Christian pacifism can be found in the scriptures of the

Roots of Christian pacifism can be found in the scriptures of the

Nonviolence: Twenty-five lessons from the history of a dangerous idea

', pp. 26–27. He was jailed for this action, but later released, eventually becoming just the third

According to the Bonifacian

According to the Bonifacian  By the

By the

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, a 1395 document of

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, a 1395 document of

The term "historical peace churches" refers to three churches—the

The term "historical peace churches" refers to three churches—the

The

The

Most Quakers, also known as Friends (members of the Religious Society of Friends), hold peace as a core value, including the refusal to participate in war going as far as forming the

Most Quakers, also known as Friends (members of the Religious Society of Friends), hold peace as a core value, including the refusal to participate in war going as far as forming the

19th-century Christian abolitionists and

19th-century Christian abolitionists and

In the winter of 1935–36, before the onset of

In the winter of 1935–36, before the onset of

Collection of works on Christian pacifism

at Internet Archive {{Subject bar , commons=yes , commons-search=Christian pacifism , q=yes , d=yes , d-search=Q4352447 Christian pacifism, Christian ethics in the Bible Christian ethics, Pacifism Christian philosophy, Pacifism Christian terminology Pacifism

Christian pacifism is the

Christian pacifism is the theological

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...

and ethical

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied e ...

position according to which pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

and non-violence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is incompatible with the Christian faith. Christian pacifists state that Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

himself was a pacifist who taught and practiced pacifism and that his followers must do likewise. Notable Christian pacifists include Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

, Adin Ballou

Adin Ballou (April 23, 1803 – August 5, 1890) was an American proponent of Christian nonresistance, Christian anarchism, and Christian socialism. He was also an abolitionist and the founder of the Hopedale Community.

Through his long career ...

, Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day, Oblate#Secular oblates, OblSB (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and Anarchism, anarchist who, after a bohemianism, bohemian youth, became a Catholic Church, Catholic without aba ...

, Ammon Hennacy

Ammon Ashford Hennacy (July 24, 1893 – January 14, 1970) was an American Christian pacifist, anarchist, Wobbly, social activist, and member of the Catholic Worker Movement. He established the Joe Hill House of Hospitality in Salt Lake City ...

, and brothers Daniel

Daniel commonly refers to:

* Daniel (given name), a masculine given name and a surname

* List of people named Daniel

* List of people with surname Daniel

* Daniel (biblical figure)

* Book of Daniel, a biblical apocalypse, "an account of the acti ...

and Philip Berrigan

Philip Francis “Phil” Berrigan (October 5, 1923 – December 6, 2002) was an American peace activist and Catholic priest with the Josephites (Maryland), Josephites. He engaged in nonviolent, civil disobedience in the cause of peace an ...

.

Christian anarchists

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answ ...

, such as Ballou and Hennacy, believe that adherence to Christianity requires not just pacifism but, because governments inevitably threatened or used force to resolve conflicts, anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

. Most Christian pacifists, including the peace churches

Peace churches are Christian churches, groups or communities advocating Christian pacifism or Biblical nonresistance. The term historic peace churches refers specifically only to three church groups among pacifist churches:

* Church of the Breth ...

, Christian Peacemaker Teams

Community Peacemaker Teams or CPT (previously called Christian Peacemaker Teams) is an international organization set up to support teams of peace workers in conflict areas around the world. The organization uses these teams to achieve its aims ...

, and individuals like John Howard Yoder, make no claim to be anarchists.

Origins

Old Testament

Roots of Christian pacifism can be found in the scriptures of the

Roots of Christian pacifism can be found in the scriptures of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

according to Baylor University professor of religion, John A. Wood. Millard C. Lind explains the theology of warfare in ancient Israel as God directing the people of Israel to trust in him, not in the warring way of the nations, and to seek peace, not coercive power. Stephen B. Chapman expresses the Old Testament describes God's divine intervention, not human power politics, or the warring king, as key to the preservation of Israel. Lind asserts the Old Testament reflects that God occasionally sanctions, even commands wars to the point of God actually fighting utilizing the forces of nature, miraculous acts or other nations. Lind further argues God fights so that Israel does not have to fight wars like other nations because God delivers them. God promised to fight for Israel, to be an enemy to their enemies and oppose all that oppose them (Exodus 23:22). Pacifist God, John Howard Yoder explains, sustained and directed his community not by power politics but by the creative power of God's word, of speaking through the law and the prophets. The scriptures in the Old Testament provide background of God's great victory over evil, sin and death. Stephen Vantassel contends the Old Testament exists to put the issue of war and killing in historical and situational context.

The role of war is developed and changes throughout the Old Testament. Chapman asserts God used war to conquer and provide the Promised Land to Israel, and then to defend that land. The Old Testament explains that Israel does not have to fight wars like other nations because God delivers them. Starting with the Exodus out of Egypt, God fights for Israel as a warrior rescuing his people from the oppressive Egyptians (Exodus 15:3). In Exodus 14:13, Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

instructs the Israelites, "The Lord will fight for you; you need only to be still." The miraculous parting of the Red Sea is God being a warrior for Israel through acts of nature and not human armies. God's promise to fight on behalf of his chosen people is affirmed in the scriptures of the Old Testament (Deuteronomy 1:30).

According to Old Testament scholar Peter C. Craige, during the military conquests of the Promised Land, the Israelites fought in real wars against real human enemies; however, it was God who granted them victory in their battles. Craige further contends God determined the outcome of human events with his participation through those humans and their activity; essentially, that God fought through the fighting of his people. Once the Promised Land was secured, and the nation of Israel progressed, God used war to protect or punish the nation of Israel with his sovereign control of the nations to achieve his purposes (2 Kings 18:9–12, Jeremiah 25:8–9, Habakkuk 1:5–11). Yoder affirms as long as Israel trusted and followed God, God would work his power through Israel to drive occupants from lands God willed them to occupy (Exodus 23:27–33). The future of Israel was dependent solely on its faith and obedience to God as mediated through the Law and prophets, and not on military strength.

Jacob Enz explains God made a covenant with his people of Israel, placing conditions on them that they were to worship only him, and be obedient to the laws of life in the Ten Commandments. When Israel trusted and obeyed God, the nation prospered; when they rebelled, God spoke through prophets such as Ezekiel and Isaiah, telling Israel that God would wage war against Israel to punish her (Isaiah 59:15–19). War was used in God's ultimate purpose of restoring peace and harmony for the whole earth with the intention towards salvation of all the nations with the coming of the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

and a new covenant. Jacob Enz describes God's plan was to use the nation of Israel for a higher purpose, and that purpose was to be the mediator between all the peoples and God. The Old Testament reflects how God helped his people of Israel, even after Israel's repeated lapses of faith, demonstrating God's grace, not violence.

The Old Testament explains God is the only giver of life and God is sovereign over human life. Man's role is to be a steward who should take care of all of God's creation, and that includes protecting human life. Craige explains God's self-revelation through his participating in human history is referred to as " Salvation History." The main objective of God's participation is man's salvation. God participates in human history by acting through people and in the world that is both in need of salvation, and is thus imperfect. God participates in the human activity of war through sinful human beings for his purpose of bringing salvation to the world.

Studies conducted by scholars Friedrich Schwally, Johannes Pedersen, Patrick D. Miller, Rudolf Smend and Gerhard von Rad maintain the wars of Israel in the Old Testament were by God's divine command. This divine activity took place in a world of sinful men and activities, such as war. God's participation through evil human activity such as war was for the sole purposes of both redemption and judgment. God's presence in these Old Testament wars does not justify or deem them holy, and instead is interpreted as serving to provide hope in a situation of hopelessness. The sixth commandment, "Thou shalt not kill" (Exodus 20:13) and the fundamental principle it holds true is that reverence for human life must be given the highest importance. The Old Testament points to a time when weapons of war shall be transformed into the instruments of peace, and the hope for the consummation of the Kingdom of God when there will be no more war. Wood points to the scriptures of Isaiah and Micah (Isaiah 2:2–4; 9:5; 11:1–9; and Micah 4:1–7) that express the pacifist view of God's plan to bring peace without violence.

Ministry of Jesus

Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

appeared to teach pacifism during his ministry when he told his disciples

A disciple is a follower and student of a mentor, teacher, or other figure. It can refer to:

Religion

* Disciple (Christianity), a student of Jesus Christ

* Twelve Apostles of Jesus, sometimes called the Twelve Disciples

* Seventy disciples in t ...

:

Early Church

SeveralChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

interpreted Jesus' teachings as advocating nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. For example, Justin Martyr

Justin, known posthumously as Justin Martyr (; ), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and Philosophy, philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and a dialogue did survive. The ''First Apolog ...

writes, "we who formerly used to murder one another do not only now refrain from making war upon our enemies, but also, that we may not lie nor deceive our examiners, willingly die confessing Christ," and, "we who were filled with war, and mutual slaughter, and every wickedness, have each through the whole earth changed our warlike weapons,—our swords into ploughshares, and our spears into implements of tillage,—and we cultivate piety...". Tatian

Tatian of Adiabene, or Tatian the Syrian or Tatian the Assyrian, (; ; ; ; – ) was an Assyrian Christian writer and theologian of the 2nd century.

Tatian's most influential work is the Diatessaron, a Biblical paraphrase, or "harmony", of the ...

writes that, "I am not anxious to be rich; I decline military command ..Die to the world, repudiating the madness that is in it"; and Aristides

Aristides ( ; , ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''díkaios''), he flourished at the beginning of Athens' Classical period and is remembered for his generalship in the Persian War. ...

writes that "Through love towards their oppressors, they persuade them to become Christians." Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome ( , ; Romanized: , – ) was a Bishop of Rome and one of the most important second–third centuries Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communitie ...

went so far as to deny soldiers

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, a warrant officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word ...

baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

: "A soldier of the civil authority must be taught not to kill men and to refuse to do so if he is commanded, and to refuse to take an oath. If he is unwilling to comply, he must be rejected for baptism." Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

formed an early argument against statolatry

Statolatry is a term formed from the word "state" and a suffix derived from the Latin and Greek word ''latria'', meaning "worship". It first appeared in Giovanni Gentile's ''Doctrine of Fascism'', published in 1931 under Mussolini's name, and was ...

, "There is no agreement between the divine and the human sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite which is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence, number and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol ...

, the standard of Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

and the standard of the devil

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or 'e ...

, the camp of light and the camp of darkness. One soul cannot be due to two masters—God and Cæsar," also writing, "the People warred: if it pleases you to sport with the subject. But how will a Christian man war, nay, how will he serve even in peace, without a sword, which the Lord has taken away?" Origen

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, Asceticism#Christianity, ascetic, and Christian theology, theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Early cent ...

, whose father Leonidus was martyred during the persecution of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

in the year AD 202, writes, "Jews ..were permitted to take up arms in defence of the members of their families, and to slay their enemies, the Christian Lawgiver asaltogether forbidden the putting of men to death ..He nowhere teaches that it is right for His own disciples to offer violence to any one, however wicked." Further examples include Arnobius

Arnobius (died c. 330) was an early Christian apologist of Berber origin during the reign of Diocletian (284–305).

According to Jerome's ''Chronicle,'' Arnobius, before his conversion, was a distinguished Numidian rhetorician at Sicca Veneri ...

, "evil ought not to be requited with evil, that it is better to suffer wrong than to inflict it, that we should rather shed our own blood than stain our hands and our conscience

A conscience is a Cognition, cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual's ethics, moral philosophy or value system. Conscience is not an elicited emotion or thought produced by associations based on i ...

with that of another, an ungrateful world is now for a long period enjoying a benefit from Christ"; Archelaus, "many oldierswere added to the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ and threw off the belt of military service"; Cyprian of Carthage

Cyprian (; ; to 14 September 258 AD''The Liturgy of the Hours according to the Roman Rite: Vol. IV.'' New York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1975. p. 1406.) was a bishop of Carthage and an early Christian writer of Berber descent, many of ...

, "The whole world is wet with mutual blood; and murder, which in the case of an individual is admitted to be a crime, is called a virtue when it is committed wholesale"; and Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius () was an early Christian author who became an advisor to Roman emperor Constantine I, guiding his Christian religious policy in its initial stages of emergence, and a tutor to his son Crispus. His most impo ...

, "For when God forbids us to kill, He not only prohibits us from open violence, which is not even allowed by the public laws, but He warns us against the commission of those things which are esteemed lawful among men. Thus it will be neither lawful for a just man to engage in warfare"; while Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( or Γρηγόριος Νυσσηνός; c. 335 – c. 394), was an early Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Nyssa from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 394. He is ve ...

conveys the spirit of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, "How can a man be master of another's life, if he is not even master of his own? Hence he ought to be poor in spirit, and look at Him who for our sake became poor of His own will; let him consider that we are all equal by nature, and not exalt himself impertinently against his own race."

Saint Maximilian of Tebessa was executed by the order of the proconsul Dion for his refusal to serve in the Roman army as he thought killing was evil; he became recognized as a Christian martyr

In Christianity, a martyr is a person who was killed for their testimony for Jesus or faith in Jesus. In the years of the early church, stories depict this often occurring through death by sawing, stoning, crucifixion, burning at the stake, or ...

. However, many early Christians also served in the army, with multiple military saint

The military saints, warrior saints and soldier saints are patron saints, martyrs and other saints associated with the military. They were originally composed of the early Christians who were soldiers in the Roman army during the persecution of ...

s before the time of Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine g ...

, and the presence of large numbers of Christians in his army may have been a factor in the conversion of Constantine to Christianity. Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

allegedly reported to the Roman Senate that his Christian soldiers fought with prayers instead of conventional weapons, which resulted in the Rain Miracle of the Marcomannic Wars

The Marcomannic Wars () were a series of wars lasting from about AD 166 until 180. These wars pitted the Roman Empire against principally the Germanic peoples, Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi and the Sarmatian Iazyges; there were related conflicts ...

.

Conversion of the Roman Empire

After the Roman Emperor Constantine converted in AD 312 and began to conquer "in Christ's name", Christianity became entangled with the state, and warfare and violence were increasingly justified by influential Christians. For example,Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

advocated for state persecution of Donatists

Donatism was a schism from the Catholic Church in the Archdiocese of Carthage from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and their prayers and sacraments to ...

, while, according to Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria ( – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Christian theologian and the 20th patriarch of Alexandria (as Athanasius ...

, "it is not right to kill, yet in war it is lawful and praiseworthy to destroy the enemy; accordingly not only are they who have distinguished themselves in the field held worthy of great honours, but monuments are put up proclaiming their achievements." Some scholars believe that "the accession of Constantine terminated the pacifist period in church history." Nevertheless, the tradition of Christian pacifism was carried on by a few dedicated Christians throughout the ages, such as Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours (; 316/3368 November 397) was the third bishop of Tours. He is the patron saint of many communities and organizations across Europe, including France's Third French Republic, Third Republic. A native of Pannonia (present-day Hung ...

, who converted during the early days of Christianity in Europe. Martin, who was then a young soldier, declared in AD 336, "I am a soldier of Christ. I cannot fight."Kurlansky, Mark (2006). Nonviolence: Twenty-five lessons from the history of a dangerous idea

', pp. 26–27. He was jailed for this action, but later released, eventually becoming just the third

Bishop of Tours

The Archdiocese of Tours (; ) is a Latin Church archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The archdiocese has roots that go back to the 3rd century, while the formal erection of the diocese dates from the 5th century.

The ecclesiastical p ...

. Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

also writes, "To die is the lot of all, to commit homicide

Homicide is an act in which a person causes the death of another person. A homicide requires only a Volition (psychology), volitional act, or an omission, that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from Accident, accidenta ...

only of the weak man."

Middle Ages

According to the Bonifacian

According to the Bonifacian hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian ...

, Boniface

Boniface, OSB (born Wynfreth; 675 –5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of Francia during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of the church i ...

, in 754, set out with a retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble, royal personage, or dignitary; a ''suite'' (French "what follows") of retainers.

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since circa 1375, stems from Old French ''retenue'', ...

for Frisia

Frisia () is a Cross-border region, cross-border Cultural area, cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. Wider definitions of "Frisia" ...

, with the hope of converting the Frisians

The Frisians () are an ethnic group indigenous to the German Bight, coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland an ...

. He baptized a great number and summoned a general meeting for confirmation at a place not far from Dokkum

Dokkum is a Dutch fortified city in the municipality of Noardeast-Fryslân in the province of Friesland. It has 12,669 inhabitants (February 8, 2020). The fortifications of Dokkum are well preserved and are known as the ''bolwerken'' (bulwarks) ...

, between Franeker

Franeker (; ) is one of the eleven historical City rights in the Low Countries, cities of Friesland and capital of the municipality of Waadhoeke. It is located north of the Van Harinxmakanaal and about west of Leeuwarden. As of 2023, it had 13,0 ...

and Groningen

Groningen ( , ; ; or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen (province), Groningen province in the Netherlands. Dubbed the "capital of the north", Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of ...

. Instead of his converts, however, a group of armed robbers appeared who slew the aged archbishop. The hagiography mention that Boniface persuaded his (armed) comrades to lay down their arms: "Cease fighting. Lay down your arms, for we are told in scripture not to render evil for evil but to overcome evil by good."

Having killed Boniface and his company, the Frisian bandits ransacked their possessions but found that the company's luggage did not contain the riches they had hoped for: "they broke open the chests containing the books and found, to their dismay, that they held manuscripts instead of gold vessels, pages of sacred texts instead of silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

plates."

The Peace and Truce of God

The Peace and Truce of God () was a movement in the Middle Ages led by the Catholic Church and was one of the most influential mass peace movements in history. The goal of both the ''Pax Dei'' and the ''Treuga Dei'' was to limit the violence o ...

was a movement in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

led by the Catholic Church and the first mass peace movement in history. The goal of both the and the was to limit the violence of feud

A feud , also known in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, private war, or mob war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially family, families or clans. Feuds begin ...

ing endemic to the western half of the former Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Franks, Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as List of Frankish kings, kings of the Franks since ...

– following its collapse in the middle of the 9th century

The 9th century was a period from 801 (represented by the Roman numerals DCCCI) through 900 (CM) in accordance with the Julian calendar.

The Carolingian Renaissance and the Viking raids occurred within this period. In the Middle East, the H ...

– using the threat of spiritual sanctions. The eastern half of the former Carolingian Empire did not experience the same collapse of central authority, and neither did England.

The Peace of God was first proclaimed in 989, at the Council of Charroux The Council of Charroux was held on June 1, 989 at Charroux Abbey in Charroux, Vienne, southeast of Poitiers, where relics of the True Cross were preserved. Meeting under the patronage of William IV, Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers, under t ...

held at Charroux, Vienne

Charroux () is a commune in the Vienne department, in the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, western France.

The remains of the Benedictine Charroux Abbey, founded in the 8th century, are preserved in the town. Said to be the site of the Council ...

. It sought to protect ecclesiastical property, agricultural resources and unarmed clerics. The Truce of God, first proclaimed in 1027 at the Council of Toulouges

Toulouges (; , ) is a commune in the Pyrénées-Orientales department in southern France.

Geography

Toulouges is located between Thuir and Perpignan, in the canton of Perpignan-6 and in the arrondissement of Perpignan.

The town covers an area ...

, attempted to limit the days of the week and times of year that the nobility engaged in violence.

By the

By the 13th century

The 13th century was the century which lasted from January 1, 1201 (represented by the Roman numerals MCCI) through December 31, 1300 (MCCC) in accordance with the Julian calendar.

The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan, which stretched ...

, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

was bold enough to declare, concerning heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

, "I answer that ..it is lawful to kill dumb animals, in so far as they are naturally directed to man's use, as the imperfect is directed to the perfect."

Cathars

Catharism

Catharism ( ; from the , "the pure ones") was a Christian quasi- dualist and pseudo-Gnostic movement which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Denounced as a he ...

was a Christian dualist

Dualism most commonly refers to:

* Mind–body dualism, a philosophical view which holds that mental phenomena are, at least in certain respects, not physical phenomena, or that the mind and the body are distinct and separable from one another

* P ...

or Gnostic

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

, particularly in northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

and southern France

Southern France, also known as the south of France or colloquially in French as , is a geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', Atlas e ...

. Followers were described as Cathars and referred to themselves as Good Christians, and are now mainly remembered for a prolonged period of persecution by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, which did not recognize their unorthodox Christianity. Catharism arrived in Western Europe in the Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

region of France in the 11th century. While most information concerning Cathar belief was written by their accusers, and therefore may be inaccurate, purportedly they were strict pacifists and rigorous ascetics

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

, abjuring war, killing, lying, swearing, and carnal relations in accordance with their understanding of the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

. Allegedly rejecting the Old Testament, Cathars despised dogmatic elements of Christianity, while their Priests ( Perfects) subsisted on a diet of little more than vegetables cooked in oil, or fish not a product of sexual union.Preece, Rod. (2008). ''Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought''. UBC Press. p. 139. is a phrase reportedly spoken by the commander of the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade (), also known as the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, what is now southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted pri ...

, prior to the massacre at Béziers

The Massacre at Béziers occurred on 22 July 1209 during the sack of Béziers by crusaders. It was the outcome of the Siege of Béziers, which was the first major military action of the Albigensian Crusade.

Background

The Albigensian Crusade w ...

on 22 July 1209. A direct translation of the Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

phrase is "Kill them. The Lord knows those that are his own."

Lollardy

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, a 1395 document of

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, a 1395 document of Lollardy

Lollardy was a proto-Protestantism, proto-Protestant Christianity, Christian religious movement that was active in England from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic C ...

, asserts that Christians should refrain from warfare, and in particular that wars given religious justifications, such as crusades, are blasphemous because Christ taught men to love and forgive their enemies.

Post-Reformation

As early as 1420,Petr Chelčický

Petr Chelčický (; c. 1390 – c. 1460) was a Czech Christian spiritual leader and author in 15th-century Bohemia, now the Czech Republic. He was one of the most influential thinkers of the Bohemian Reformation. Chelčický inspired the Uni ...

taught that Christians must never use violence or killing. Chelčický used the parable of the wheat and the tares (Matthew 13:24–30) to show that both the sinners and the saints should be allowed to live together until the harvest. He thought that it is wrong to kill even the sinful and that Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

should refuse military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job (volunteer military, volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

Few nations, such ...

. He argued that if the poor refused, the lords would have no one to go to war for them. Since then, many other Christians have made similar stands for pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

as the following quotes show:

Charles Spurgeon

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (19 June 1834 – 31st January 1892) was an English Particular Baptist preacher. Spurgeon remains highly influential among Christians of various denominations, to some of whom he is known as the "Prince of Preachers." ...

did not explicitly identify as a pacifist but expressed very strongly worded anti-war sentiment."Long have I held that war is an enormous crime; long have I regarded all battles as but murder on a large scale." "India's Ills and England's Sorrows", September 6, 1857 Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

wrote extensively on Christian pacifism, while Mohandas K. Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ru ...

considered Tolstoy's ''The Kingdom of God is Within You

''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform ) is a non-fiction book written by Leo Tolstoy. A Christian anarchist philosophical treatise, the book was first published in Germany in 1894 after being banned in his home ...

'' as the text to have the most influence in his life.

Christian pacifist denominations

The firstconscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

in the modern sense was a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

in 1815. Some Quakers had originally served in Cromwell's New Model Army

The New Model Army or New Modelled Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 t ...

before the peace testimony

The testimony of peace ( testimony for peace or testimony against war) is the action generally taken by members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) for peace and against participation in war. Like other Quaker testimonies, it is not a ...

of Friends was issued after the restoration of the British monarchy in 1660. A number of Christian denominations have taken pacifist positions institutionally, including the Quakers and Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

s.

The term "historical peace churches" refers to three churches—the

The term "historical peace churches" refers to three churches—the Church of the Brethren

The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition ( "Schwarzenau New Baptists") that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germany during the Radical Pietist revival. ...

, the Mennonites and the Quakers—who took part in the first peace church conference, in Kansas in 1935, and who have worked together to represent the view of Christian pacifism. Of these, both Mennonites and the Schwarzenau Brethren are Anabaptist Churches.

Anabaptist churches

Traditionally,Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. The term (tra ...

hold firmly to their beliefs in nonviolence. Many of these churches continue to advocate nonviolence, including the Anabaptist traditions of the Mennonites

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

, the Amish

The Amish (, also or ; ; ), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, church fellowships with Swiss people, Swiss and Alsace, Alsatian origins. As they ...

, the Hutterite

Hutterites (; ), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Reformation of the early 16th century and have formed intent ...

s, the Schwarzenau Brethren

The Schwarzenau Brethren, the German Baptist Brethren, Dunkers, Dunkard Brethren, Tunkers, or sometimes simply called the German Baptists, are an Anabaptist group that dissented from Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed European state churches ...

, the River Brethren

The River Brethren are a group of historically related Anabaptist Christian denominations originating in 1770, during the Radical Pietist movement among German colonists in Pennsylvania. In the 17th century, Mennonite refugees from Switzerl ...

(such as the Old Order River Brethren

The Old Order River Brethren, formerly sometimes known as York Brethren or Yorkers, are a River Brethren denomination of Anabaptist Christianity with roots in the Radical Pietist movement. As their name indicates, they are Old Order Anabaptis ...

and Brethren in Christ

The Brethren in Christ Church (BIC) is a River Brethren Christian denomination. Falling within the Anabaptist tradition of Christianity, the Brethren in Christ Church has roots in the Mennonite church, with influences from the revivals of Radic ...

), the Apostolic Christian Church

The Apostolic Christian Church (ACC) is a worldwide Christian denomination from the Anabaptist tradition that practices credobaptism, closed communion, greeting other believers with a holy kiss, a capella worship in some branches (in others, ...

, and the Bruderhof Communities

The Bruderhof (; German for 'place of brothers') is a communal Anabaptist Christian movement that was founded in Germany in 1920 by Eberhard Arnold. The movement has communities in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Paragu ...

.

Christadelphians

Although the group had already separated from theCampbellite

Campbellite is a mildly pejorative term referring to adherents of certain religious groups that have historic roots in the Restoration Movement, among whose most prominent 19th-century leaders were Thomas and Alexander Campbell.

Influence of the ...

s, a part of the Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement (also known as the American Restoration Movement or the Stone–Campbell Movement, and pejoratively as Campbellism) is a Christian movement that began on the American frontier during the Second Great Awakening (1790–1 ...

, after 1848 for theological reasons as the "Royal Assembly of Believers", among other names, the "Christadelphians

The Christadelphians () are a Restorationism, restorationist and Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Biblical unitarianism, (Biblical Unitarian) Christian denomination. The name means 'brothers and sisters in Christ',"The Christadelphians, or breth ...

" formed as a church formally in 1863 in response to conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. They are one of the few churches to have been legally formed over the issue of Christian pacifism. The British and Canadian arms of the group adopted the name "Christadelphian" in the following year, 1864, and also maintained objection to military service during the First and Second World Wars. Unlike Quakers, Christadelphians generally refused all forms of military service, including stretcher bearers and medics, preferring non-uniformed civil hospital service.

Churches of God (7th day)

The different groups evolving under the nameChurch of God (7th day)

The Churches of God (Seventh Day) is composed of a number of sabbath-keeping churches, among which the General Conference of the Church of God, or simply CoG7, is the best-known organization. The Churches of God (Seventh Day) observe the Sabba ...

stand opposed to carnal warfare, based on Matthew 26:52; Revelation 13:10; Romans 12:19–21. They believe the weapons of their warfare to not be carnal but spiritual (II Corinthians 10:3–5; Ephesians 6:11–18).

Doukhobors

TheDoukhobors

The Doukhobors ( Canadian spelling) or Dukhobors (; ) are a Spiritual Christian ethnoreligious group of Russian origin. They are known for their pacifism and tradition of oral history, hymn-singing, and verse. They reject the Russian Ortho ...

are a Spiritual Christian

Spiritual Christianity () is the group of belief systems held by so-called folk Protestants (), including non-Eastern Orthodox indigenous faith tribes and new religious movements that emerged in the Russian Empire. Their origins are varied: some ...

denomination that advocate pacifism. On June 29, 1895, the Doukhobors, in what is known as the "Burning of the Arms", "piled up their swords, guns, and other weapons and burned them in large bonfires while they sang psalms".

Holiness pacifists

The Wesleyan Methodist Church, one of the first Methodist denominations of theholiness movement

The Holiness movement is a Christianity, Christian movement that emerged chiefly within 19th-century Methodism, and to a lesser extent influenced other traditions such as Quakers, Quakerism, Anabaptism, and Restorationism. Churches aligned with ...

, opposed war as documented in their 1844 ''Book of Discipline

A Book of Discipline (or in its shortened form Discipline) is a book detailing the beliefs, standards, doctrines, canon law, and polity of a particular Christian denomination. They are often re-written by the governing body of the church concern ...

'', that noted that the Gospel is in "every way opposed to the practice of War in all its forms; and those customs which tend to foster and perpetuate war spirit, reinconsistent with the benevolent designs of the Christian religion."

The Reformed Free Methodist Church

The Reformed Free Methodist Church (RFMC) was a Methodist denomination in the conservative holiness movement.

History

The formation of the Reformed Free Methodist Church is a part of the history of Methodism in the United States; it was founded i ...

, Emmanuel Association

__NOTOC__

The Emmanuel Association of Churches is a Methodist denomination in the conservative holiness movement.

The formation of the Emmanuel Association is a part of the history of Methodism in the United States. It was formed in 1937 as a res ...

, Immanuel Missionary Church

The Immanuel Missionary Church (IMC) is a Methodist denomination within the conservative holiness movement.

The formation of the Immanuel Missionary Church is a part of the history of Methodism in the United States. The Immanuel Missionary Chu ...

, Church of God (Guthrie, Oklahoma)

The Church of God (Guthrie, Oklahoma), also known as the Church of God Evening Light, is a Christian denomination in the Wesleyan-Arminian and Restorationist traditions, being aligned with the conservative holiness movement.

History

The origi ...

, First Bible Holiness Church, and Christ's Sanctified Holy Church

Christ's Sanctified Holy Church is a Methodist denomination aligned with the holiness movement. It is based in the Southeastern United States. The group was organized on February 14, 1892, by members of the Methodist Episcopal Church on Chincoteag ...

are denominations in the holiness movement known for their opposition to war today; they are known as "holiness pacifists". The Emmanuel Association teaches:

Jehovah's Witnesses

The beliefs and practices ofJehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-fou ...

have engendered controversy throughout their history. Consequently, the denomination has been opposed by local governments, communities, and religious groups. Many Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is a distinct Religion, religious body within Christianity that comprises all Church (congregation), church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadersh ...

s consider the interpretations and doctrines of Jehovah's Witnesses heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

, and some professors of religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

have classified the denomination as a cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

.

According to law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

professor Archibald Cox

Archibald Cox Jr. (May 17, 1912 – May 29, 2004) was an American legal scholar who served as United States Solicitor General, U.S. Solicitor General under President John F. Kennedy and as a special prosecutor during the Watergate scandal. During ...

, Jehovah's Witnesses in the United States were "the principal victims of religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

... they began to attract attention and provoke repression in the 1930s, when their proselytizing and numbers rapidly increased." At times, political and religious animosity against Jehovah's Witnesses has led to mob action

Mob rule or ochlocracy or mobocracy is a pejorative term describing an oppressive majoritarian form of government controlled by the common people through the intimidation of authorities. Ochlocracy is distinguished from democracy or similarly ...

and government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

al repression in various countries including the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Jehovah's Witnesses were targeted in the United States, Canada, and many other countries because they refused to serve in the military or contribute to the war effort due to their doctrine of political neutrality. In Canada, Jehovah's Witnesses were interned in camps along with political dissidents and people of Japanese and Chinese descent.

Molokans

TheMolokan

The Molokans ( rus, молокан, p=məlɐˈkan or , "dairy-eater") are a Russian Spiritual Christian sect that evolved from Eastern Orthodoxy in the East Slavic lands. Their traditions, especially dairy consumption during Christian fasts, ...

s are a Spiritual Christian denomination that advocate pacifism. They have historically been persecuted

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these terms ...

for failing to bear arms.

Moravian Church

The

The Moravian Church

The Moravian Church, or the Moravian Brethren ( or ), formally the (Latin: "Unity of the Brethren"), is one of the oldest Protestant denominations in Christianity, dating back to the Bohemian Reformation of the 15th century and the original ...

historically adheres to the position of Christian pacifism, evidenced in atrocities such as the Gnadenhutten massacre

The Gnadenhutten massacre, also known as the Moravian massacre, was the killing of 96 pacifist Moravian Christian Indians (primarily Lenape and Mohican) by U.S. militiamen from Pennsylvania, under the command of David Williamson, on March 8, ...

, where the Lenape Moravian martyrs practiced nonresistance

Nonresistance (or non-resistance) is "the practice or principle of not resisting authority, even when it is unjustly exercised". At its core is discouragement of, even opposition to, physical resistance to an enemy. It is considered as a form of pr ...

with their murderers, singing hymns until their execution by American revolutionaries.

Quakers

Most Quakers, also known as Friends (members of the Religious Society of Friends), hold peace as a core value, including the refusal to participate in war going as far as forming the

Most Quakers, also known as Friends (members of the Religious Society of Friends), hold peace as a core value, including the refusal to participate in war going as far as forming the Friends' Ambulance Unit

The Friends' Ambulance Unit (FAU) was a volunteer ambulance service, founded by individual members of the British Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), in line with their Peace Testimony. The FAU operated from 1914 to 1919, 1939 to 1946 and ...

with the aim of "co-operating with others to build up a new world rather than fighting to destroy the old", and the American Friends Service Committee

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Religious Society of Friends ('' Quaker)-founded'' organization working for peace and social justice in the United States and around the world. AFSC was founded in 1917 as a combined effort by ...

during the two World Wars and subsequent conflicts.

Shakers

Shakers

The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a Millenarianism, millenarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian sect founded in England and then organized in the Unit ...

, who emerged in part from Quakerism in 1747, do not believe that it is acceptable to kill or harm others, even in times of war.

Seventh-day Adventists

During the American Civil War in 1864, shortly after the formation of theSeventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sa ...

, the Seventh-day Adventists declared, "The denomination of Christians calling themselves Seventh-day Adventists, taking the Bible as their rule of faith and practice, are unanimous in their views that its teaching are contrary to the spirit and practice of war; hence, they have ever been conscientiously opposed to bearing arms."

The general Adventist movement from 1867 followed a policy of conscientious objection

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

. This was confirmed by the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1914. The official policy allows for military service in non-combative roles such as medical corps much like Seventh-day Adventist Desmond Doss

Desmond Thomas Doss (February 7, 1919 – March 23, 2006) was a United States Army corporal who served as a combat medic with an infantry company in World War II. Due to his religious beliefs, he refused to carry a weapon.

He was twice awa ...

who was the first conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor and one of only three so honored, and other supportive roles which do not require to kill or carry a weapon. In practice today, as a pastor from the Seventh-day Adventist church comments in an online magazine runs by members of the Seventh-day Adventist church: "Today in a volunteer army a lot of Adventist young men and women join the military in combat positions, and there are many Adventist pastors electing for military chaplaincy positions, supporting combatants and non-combatants alike. On Veteran's Day, American churches across the country take time to give honor and respect to those who 'served their country,' without any attempt to differentiate how they served, whether as bomber pilots, Navy Seals, or Operation Whitecoat

Operation Whitecoat was a biodefense medical research program carried out by the United States Army at Fort Detrick, Maryland, between 1954 and 1973. The program pursued medical research using volunteer enlisted personnel who were eventually nic ...

guinea pigs. I have yet to see a service honoring those who ran away to Canada to avoid participation in the senseless carnage of Vietnam in their Biblical pacifism."

Other denominations

Anglicanism

Lambeth Conference 1930 Resolution 25 declares that, "The Conference affirms that war as a method of settling international disputes is incompatible with the teaching and example of our Lord Jesus Christ." The 1948, 1958 and 1968 conferences re-ratified this position. TheAnglican Pacifist Fellowship The Anglican Pacifist Fellowship (APF) is a body of people within the Anglican Communion who reject war as a means of solving international disputes, and believe that peace and justice should be sought through nonviolence, nonviolent means.

Belief ...

lobbies the various dioceses of the church to uphold this resolution and work constructively for peace.

Baptist

Some 400Baptists

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

refused combatant duty during World War II.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

was an American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesman and leader in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. An African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

church leader and the son of early civil rights activist and minister Martin Luther King Sr., King advanced civil rights for people of color in the United States through nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

and civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

.

Many modern Calvinists, such as André Trocmé

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese language, Portuguese form of the name Andrew and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French language, French-spe ...

, have been pacifists.

Lutheranism

TheLutheran Church of Australia

The Lutheran Church of Australia (LCA) is the major Lutheran denomination in Australia and New Zealand. It was created from a merger of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Australia and the United Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia in 1966 ...

recognises conscientious objection to war as Biblically legitimate.

Since the Second World War, many notable Lutherans have been pacifists.

Secular interpretations

According to the acclaimed 20th centurysocialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

writer Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker journalist, and political activist, and the 1934 California gubernatorial election, 1934 Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

,

Linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, cognitive scientist

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition (in a broad sense). Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include percep ...

, social critic

Social criticism is a form of academic or journalistic criticism focusing on social issues in contemporary society, in respect to perceived injustices and power relations in general.

Social criticism of the Enlightenment

The origin of modern ...

, and libertarian socialist

Libertarian socialism is an anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist political current that emphasises self-governance and workers' self-management. It is contrasted from other forms of socialism by its rejection of state ownership and from other ...

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

writes,

Christian pacifism in action

19th-century Christian abolitionists and

19th-century Christian abolitionists and anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

Adin Ballou

Adin Ballou (April 23, 1803 – August 5, 1890) was an American proponent of Christian nonresistance, Christian anarchism, and Christian socialism. He was also an abolitionist and the founder of the Hopedale Community.

Through his long career ...

and William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

were critical of the violent and coercive nature of all human governments. Ballou and Garrison advocated for nonresistance against the institution of slavery and imperialism, as they saw the Bible as the embodiment of “passive nonresistance” and the only way to achieve the new millennium on Earth. Instead of violence, they advocated for moral suasion

Moral suasion is an appeal to morality, in order to influence or change behavior. A famous example is the attempt by William Lloyd Garrison and his American Anti-Slavery Society to end slavery in the United States by arguing that the practice w ...

or consistent rebukes against the institution of slavery so to persuade racist southerns and indifferent northerners to the abolitionist's cause. Garrison and Ballou, along with Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and av ...

, Maria Weston Chapman

Maria Weston Chapman (July 25, 1806 – July 12, 1885) was an American abolitionist. She was elected to the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and from 1839 until 1842, she served as editor of the anti-slavery journ ...

, Stephen Symonds Foster

Stephen Symonds Foster (November 17, 1809 – September 13, 1881) was a radical American abolitionist known for his dramatic and aggressive style of public speaking, and for his stance against those in the church who failed to fight slavery. His ma ...

, Abby Kelley

Abby Kelley Foster (January 15, 1811 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-S ...

, Samuel May

Samuel Joseph May (September 12, 1797 – July 1, 1871) was an American reformer during the nineteenth century who championed education, women's rights, and abolition of slavery. May argued on behalf of all working people that the rights of ...

, and Henry C. Wright

Henry Clarke Wright (August 29, 1797 – August 16, 1870) was an American abolitionist, pacifist, anarchist and feminist. He was fervent in his beliefs and often was more extreme in his rhetoric than other peace activists or abolitionists. Wright ...

, founded the New England Non-Resistance Society The New England Non-Resistance Society was an American peace group founded at a special peace convention organized by William Lloyd Garrison, in Boston in September 1838.Peter Brock ''Pacifism in the United States, from the Colonial era to the First ...

in 1838 in Boston. The society condemned the use of force in resisting evil, in war, for the death penalty, or in self-defense, renounced allegiance to human government, and called for the immediate abolition of slavery without compensation. Garrison's weekly abolitionist newspaper '' The Liberator'' (1831–1865) and Ballou's Christian utopian commune the Hopedale Community

The Hopedale Community was founded in Milford, Massachusetts, in 1843 by Adin Ballou. He and his followers purchased of land on which they built homes for the community members, chapels and the factories for which the company was initially formed. ...

(established in 1843 in Milford, Massachusetts

Milford is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 30,379 according to the 2020 census. First settled in 1662 and incorporated in 1780, Milford became a booming industrial and quarrying community in the 19th ...

) were also some of their key efforts in propagating Christian pacifism in the United States. Their writings on Christian nonresistance also influenced Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

's theo-political ideology and his non-fiction texts like ''The Kingdom of God is Within You

''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform ) is a non-fiction book written by Leo Tolstoy. A Christian anarchist philosophical treatise, the book was first published in Germany in 1894 after being banned in his home ...

.''

Before Tolstoy, and similar to Northern Abolitionists (though from a Southern anti-slavery viewpoint), David Lipscomb

David Lipscomb (January 21, 1831 – November 11, 1917) was a minister, editor, and educator in the American Restoration Movement and one of the leaders of that movement, which, by 1906, had formalized a division into the Church of Christ (w ...

argued in 1866–1867 that Christians could not support warfare and should not vote, because human governments throughout history waged wars. His book, ''Civil Government: Its Origin, Mission, and Destiny, and The Christian's Relation To It'', maintained a Christian pacifist and proto-anarchist position in the wake of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

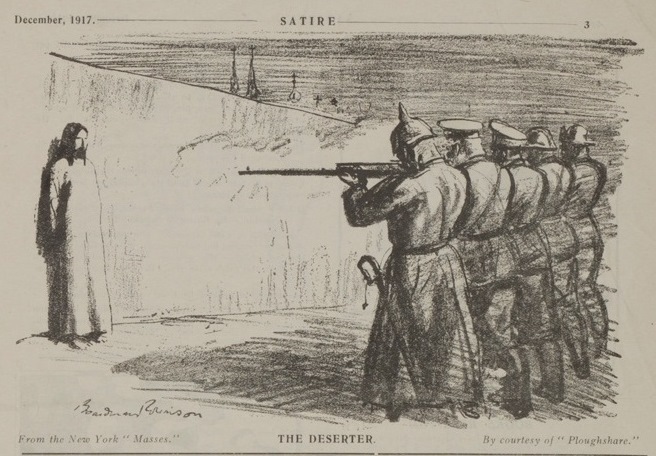

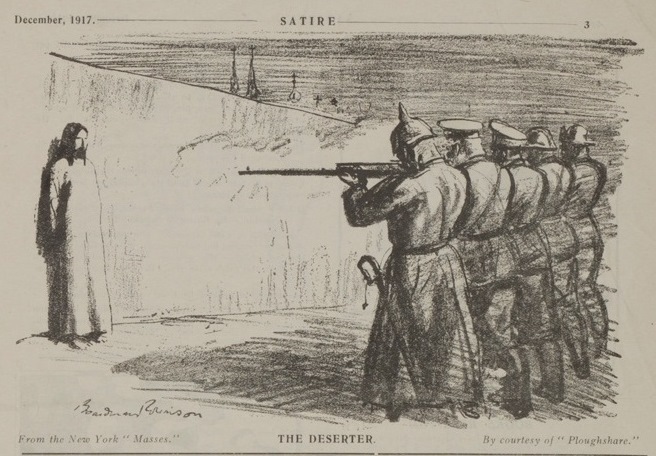

From the beginning of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Christian pacifist organizations emerged to support Christians in denominations other than the historic peace churches. The first was the interdenominational Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...

("FoR"), founded in Britain in 1915 but soon joined by sister organizations in the U.S. and other countries. Today pacifist organizations serving specific denominations are more or less closely allied with the FoR: they include the Methodist Peace Fellowship (established in 1933), the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship (established in 1937), Pax Christi