Child sacrifice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Child sacrifice is the

Child sacrifice is the

The

The

The Moche of northern

The Moche of northern

Child sacrifice is the

Child sacrifice is the ritual

A ritual is a repeated, structured sequence of actions or behaviors that alters the internal or external state of an individual, group, or environment, regardless of conscious understanding, emotional context, or symbolic meaning. Traditionally ...

istic killing of child

A child () is a human being between the stages of childbirth, birth and puberty, or between the Development of the human body, developmental period of infancy and puberty. The term may also refer to an unborn human being. In English-speaking ...

ren in order to please or appease a deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over some aspect of the universe and/or life. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines ''deity'' as a God (male deity), god or god ...

, supernatural

Supernatural phenomena or entities are those beyond the Scientific law, laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin 'above, beyond, outside of' + 'nature'. Although the corollary term "nature" has had multiple meanin ...

beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

.

Child sacrifice is thought to be an extreme extension of the idea that the more important the object of sacrifice, the more devout the person rendering it.

The practice of child sacrifice in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

appears to have ended as a part of the religious transformations of late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

.

Pre-Columbian cultures

Archaeologists have found the remains of more than 140 children who were sacrificed in Peru's northern coastal region.Aztec culture

The

The Aztecs

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the ...

are well known for their ritualistic human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

as offerings to gods with the goal of restoring cosmological balance. While the demographic of people chosen to sacrifice remains unclear, there is evidence that victims were mostly warriors captured in battle and slaves in the slave trade. Human sacrifice was not limited to adults, however; 16th century Spanish codices chronicled child sacrifice to Aztec rain gods. In 2008, archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

found and excavated 43 victims of Aztec sacrifice, 37 of which were children. The sacrificial victims were found by Temple R, a temple in Tlatelolco, the ancient Aztec city which is now Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

. Temple R was dedicated to the Aztec rain gods, including Tlāloc, Ehecatl, Quetzalcoatl, and Huītzilōpōchtli

Huitzilopochtli (, ) is the Solar deity, solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associatin ...

. A majority (66%) of the excavated subadults were under 3 years old, and 32 subadults as well as 6 adults were identified as male, although the sex determination results could be replicated only for 26 of the 38 individuals.

It is hypothesized that this specific child sacrifice took place during the great drought and famine of 1454–1457, furthering the theory that Aztecs utilized human sacrifice to placate the gods. Osteological and dental pathological evidence shows that many of the child sacrificial victims had varying health issues, and it is suggested that the Tlaloques selected these children who had medical ailments. Because sacrificial victims typically embodied the gods they were being sacrificed to, male child sacrifices were more present at this site due to the masculine nature of the Aztec rain gods.

Inca culture

TheInca

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

culture sacrificed children in a ritual called '' qhapaq hucha''. Their frozen corpses have been discovered in the South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

n mountaintops. The first of these corpses, a female child who had died from a blow to the skull, was discovered in 1995 by Johan Reinhard. Other methods of sacrifice included strangulation

Strangling or strangulation is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain by restricting the flow of oxygen through the trachea. Fatal strangulation typically occurs ...

and simply leaving the children, who had been given an intoxicating drink, to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and low-oxygen conditions of the mountaintop, and to die of hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

.

Maya culture

InMaya

Maya may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Mayan languages, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (East Africa), a p ...

culture, people believed that supernatural beings had power over their lives and this is one reason that child sacrifice occurred. The sacrifices were essentially to satisfy the supernatural beings. This was done through ''k'ex'', which is an exchange or substitution of something. Through ''k'ex'' infants would substitute more powerful humans. It was thought that supernatural beings would consume the souls of more powerful humans and infants were substituted in order to prevent that. Infants are believed to be good offerings because they have a close connection to the spirit world through liminality

In anthropology, liminality () is the quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of a rite of passage, when participants no longer hold their pre-ritual status but have not yet begun the transition to the status they ...

. It is also believed that parents in Maya culture would offer their children for sacrifice and depictions of this show that this was a very emotional time for the parents, but they would carry through because they thought the child would continue existing. It is also known that infant sacrifices occurred at certain times. Child sacrifice was preferred when there was a time of crisis and transitional times such as famine and drought.

There is archaeological evidence of infant sacrifice in tombs where the infant has been buried in urns or ceramic vessels. There have also been depictions of child sacrifice in art. Some art includes pottery and stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

s as well as references to infant sacrifice in mythology and art depictions of the mythology.

Moche culture

The Moche of northern

The Moche of northern Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

practiced mass sacrifices of men and boys. Archeologists found the remains of 137 children and 3 adults, along with 200 camelids, during excavations in 2011, 2014 and 2016, beneath the sands of a 15th-century site called Huanchaquito-Las Llamas. This sacrifice was possibly made during the heavy rains as there was a layer of mud on top of the clean sand.

Timoto-Cuica culture

The Timoto-Cuicas offered human sacrifices. Until colonial times children sacrifice persisted secretly in Laguna de Urao ( Mérida). It was described by the chronicler Juan de Castellanos, who cited that feasts and human sacrifices were done in honour of Icaque, an Andean prehispanic goddess.Ancient Near East

Tanakh

TheTanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' According to scholars such as Otto Eissfeldt, Paul G. Mosca, and Susan Ackerman, Moloch was not a name for a god, but instead is a word for a particular form of child sacrifice practiced in Israel and Judah which was not abandoned until the reforms of

According to scholars such as Otto Eissfeldt, Paul G. Mosca, and Susan Ackerman, Moloch was not a name for a god, but instead is a word for a particular form of child sacrifice practiced in Israel and Judah which was not abandoned until the reforms of

Genesis 22 relates the

Genesis 22 relates the

. ''

ancient Near Eastern

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Ne ...

practice. The king of Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (''olah'', as used of the Temple sacrifice). In the book of the prophet Micah, the question is asked, 'Shall I give my firstborn for my sin, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?', and responded to in the phrase, 'He has shown all you people what is good. And what does Yahweh require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.' The Tanakh also implies that the Ammonites

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

offered child sacrifices to Moloch

Moloch, Molech, or Molek is a word which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the Book of Leviticus. The Greek Septuagint translates many of these instances as "their king", but maintains the word or name ''Moloch'' in others, ...

.

According to scholars such as Otto Eissfeldt, Paul G. Mosca, and Susan Ackerman, Moloch was not a name for a god, but instead is a word for a particular form of child sacrifice practiced in Israel and Judah which was not abandoned until the reforms of

According to scholars such as Otto Eissfeldt, Paul G. Mosca, and Susan Ackerman, Moloch was not a name for a god, but instead is a word for a particular form of child sacrifice practiced in Israel and Judah which was not abandoned until the reforms of Josiah

Josiah () or Yoshiyahu was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE). According to the Hebrew Bible, he instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Until the 1990s, the biblical description of Josiah’s ...

. In the Tanakh mentions are made in books such as Kings, Leviticus, and Jeremiah

Jeremiah ( – ), also called Jeremias, was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewish tradition, Jeremiah authored the Book of Jeremiah, book that bears his name, the Books of Kings, and the Book of Lamentations, with t ...

of children being given "to the ''mōlek''". According to Patrick D. Miller these child sacrifice traditions were not originally part of the Yahwism, but were instead foreign imports. Francesca Stavrakopoulou

Francesca Stavrakopoulou ( ; ; born 3 October 1975) is a British biblical scholar and broadcaster. She is currently Professor of Hebrew Bible and Ancient Religion at the University of Exeter. The main focus of her research is on the Hebrew Bible ...

contradicts this, asserting that sacrifices were native to Israel and part of the royal line's attempts to perpetuate itself.

states "The firstborn of your sons you shall give to me" potentially a demand by Yahweh that the firstborn children of the Israelites must be sacrificed to him. However, Jacob Milgrom argues that Yahweh forbids human sacrifice and that in Exodus 22:28b-29, as in the Day of Atonement, Yahweh instituted substitutionary animal sacrifices for human sin and the redemption of the firstborn in Israelite families (cf. ). Yahweh also states to the prophet Jeremiah, “They have built the high places of Topheth in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to burn their sons and daughters in the fire—something I did not command, nor did it enter my mind,” (Jeremiah 7:31) which some scholars interpret as indicating that it was once viewed as a central part to the law and desire of Yahweh.

Binding of Isaac

Genesis 22 relates the

Genesis 22 relates the binding of Isaac

The Binding of Isaac (), or simply "The Binding" (), is a story from Book of Genesis#Patriarchal age (chapters 12–50), chapter 22 of the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. In the biblical narrative, God in Abrahamic religions, God orders A ...

, by Abraham to present his son, Isaac

Isaac ( ; ; ; ; ; ) is one of the three patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith. Isaac first appears in the Torah, in wh ...

, as a sacrifice on Mount Moriah. It was a test of faith (Genesis 22:12). Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an angel

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

stopping Abraham at the last minute and making Isaac's sacrifice unnecessary by providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. Other interpretations of the text have contradicted this version. For example, Martin S. Bergmann states "The Aggadah

Aggadah (, or ; ; 'tales', 'legend', 'lore') is the non-legalistic exegesis which appears in the classical rabbinic literature of Judaism, particularly the Talmud and Midrash. In general, Aggadah is a compendium of rabbinic texts that incorporat ...

rabbis asserted that "father Isaac was bound on the altar and reduced to ashes, and his sacrificial dust was cast on Mount Moriah." A similar interpretation was made in the Epistle to the Hebrews

The Epistle to the Hebrews () is one of the books of the New Testament.

The text does not mention the name of its author, but was traditionally attributed to Paul the Apostle; most of the Ancient Greek manuscripts, the Old Syriac Peshitto and ...

. Margaret Barker notes that "Abraham returned to Bersheeba without Isaac" according to , a possible sign that he was indeed sacrificed. Barker also stated that wall paintings in the ancient Dura-Europos synagogue

The Dura-Europos synagogue was an Historic synagogues, ancient Judaism, Jewish former synagogue discovered in 1932 at Dura-Europos, Syria. The former synagogue contained a forecourt and house of assembly with painted walls depicting people and ...

explicitly show Isaac being sacrificed, followed by his soul traveling to heaven. According to Jon D. Levenson a part of Jewish tradition interpreted Isaac as having been sacrificed. Similarly the German theologians and maintain that due to the grammatical perfect tense

The perfect tense or aspect (abbreviated or ) is a verb form that indicates that an action or circumstance occurred earlier than the time under consideration, often focusing attention on the resulting state rather than on the occurrence itself. A ...

used to describe Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac, he did, in fact, follow through with the action.

Rabbi A.I. Kook, first Chief Rabbi of Israel, stressed that the climax of the story, commanding Abraham not to sacrifice Isaac, is the whole point: to put an end to, and God's total aversion to the ritual of child sacrifice. According to Irving Greenberg the story of the binding of Isaac

The Binding of Isaac (), or simply "The Binding" (), is a story from Book of Genesis#Patriarchal age (chapters 12–50), chapter 22 of the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. In the biblical narrative, God in Abrahamic religions, God orders A ...

, symbolizes the prohibition to worship God by human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

s, at a time when human sacrifices were the norm worldwide.

Ban in Leviticus

In Leviticus 18:21, 20:3 and Deuteronomy 12:30–31, 18:10, theTorah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

contains a number of imprecations against and laws forbidding child sacrifice and human sacrifice in general. The Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. ''

In the

In the

. ''

Baal

Baal (), or Baʻal, was a title and honorific meaning 'owner' or 'lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The ...

worshippers (e.g. Psalms 106:37).

James Kugel argues that the Torah's specifically forbidding child sacrifice indicates that it happened in Israel as well. The biblical scholar Mark S. Smith argues that the mention of "Tophet" in Isaiah 30:27–33 indicates an acceptance of child sacrifice in the early Jerusalem practices, to which the law in Leviticus 20:2–5 forbidding child sacrifice is a response. Some scholars have stated that at least some Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

and Judahites believed child sacrifice was a legitimate religious practice.

Numbers 31

In the aftermath of the War against the Midianites narrated in Numbers 31, the Israelites appear to be dedicating 32 captive Midianite virgin girls to be sacrificed to Yahweh as his share in the spoils of war.Gehenna and Tophet

The most extensive accounts of child sacrifice in the Hebrew torah Tanakh refer to those carried out inGehenna

Gehenna ( ; ) or Gehinnom ( or ) is a Biblical toponym that has acquired various theological connotations, including as a place of divine punishment, in Jewish eschatology.

The place is first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as part of the border ...

by two kings of Judah, Ahaz

Ahaz (; ''Akhaz''; ) an abbreviation of Jehoahaz II (of Judah), "Yahweh has held" (; ''Ya'úḫazi'' 'ia-ú-ḫa-zi'' Hayim Tadmor and Shigeo Yamada, ''The Royal Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III (744-727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726-722 BC), ...

and Manasseh of Judah

Manasseh (; Hebrew: ''Mənaššé'', "Forgetter"; ''Menasî'' 'me-na-si-i'' ''Manasses''; ) was the fourteenth king of the Kingdom of Judah. He was the oldest of the sons of Hezekiah and Hephzibah (). He became king at the age of 12 and re ...

.

Jephthah's daughter

In the

In the Book of Judges

The Book of Judges is the seventh book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. In the narrative of the Hebrew Bible, it covers the time between the conquest described in the Book of Joshua and the establishment of a kingdom in the ...

, chapter 11, the figure of Jephthah

Jephthah (pronounced ; , ''Yiftāḥ'') appears in the Book of Judges as a judge who presided over Israel for a period of six years (). According to Judges, he lived in Gilead. His father's name is also given as Gilead, and, as his mother is de ...

makes a vow to God, saying, "If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering" (as worded in the New International Version

The New International Version (NIV) is a translation of the Bible into contemporary English. Published by Biblica, the complete NIV was released on October 27, 1978, with a minor revision in 1984 and a major revision in 2011. The NIV relies ...

). Jephthah succeeds in winning a victory, but when he returns to his home in Mizpah he sees his daughter, dancing to the sound of timbrels, outside. After allowing her two months preparation, Judges 11:39 states that Jephthah kept his vow. According to the commentators of the rabbinic Jewish tradition, Jepthah's daughter was not sacrificed but was forbidden to marry and remained a spinster her entire life, fulfilling the vow that she would be devoted to the Lord. Radak, Book of Judges

The Book of Judges is the seventh book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. In the narrative of the Hebrew Bible, it covers the time between the conquest described in the Book of Joshua and the establishment of a kingdom in the ...

11:39; ''Metzudas Dovid'' ibid The 1st-century CE Jewish historian Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing ''The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Judaea ...

, however, interpreted this to mean that Jephthah burned his daughter on Yahweh's altar, whilst pseudo-Philo, late first century CE, wrote that Jephthah offered his daughter as a burnt offering because he could find no sage in Israel who would cancel his vow. In other words, this story of human sacrifice is not an order or requirement by God, but the punishment for those who vowed to sacrifice humans.

Phoenicia and Carthage

The practice of child sacrifice among Canaanite groups is attested by numerous sources spanning over a millennium. One example is in the writings ofDiodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

:

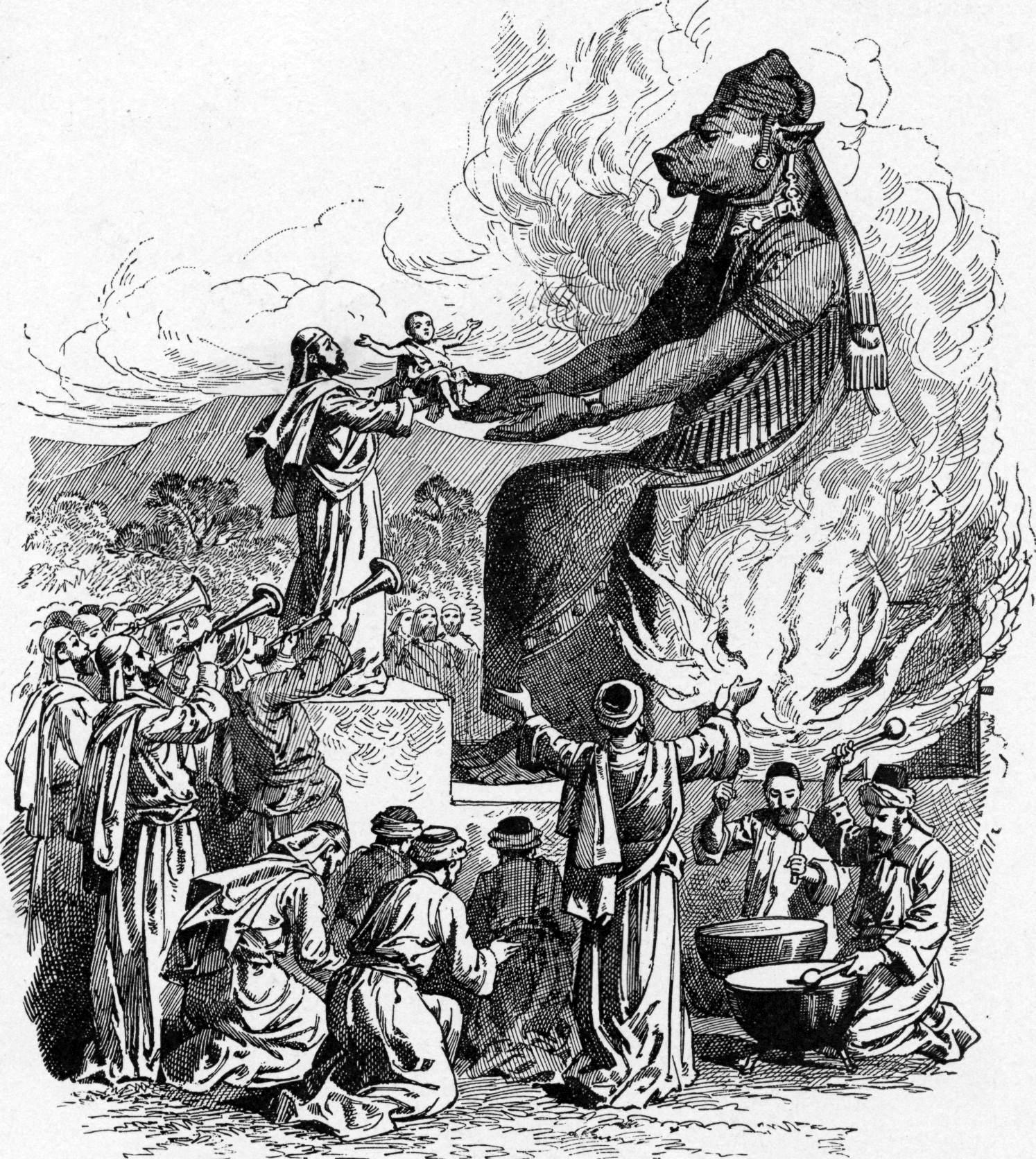

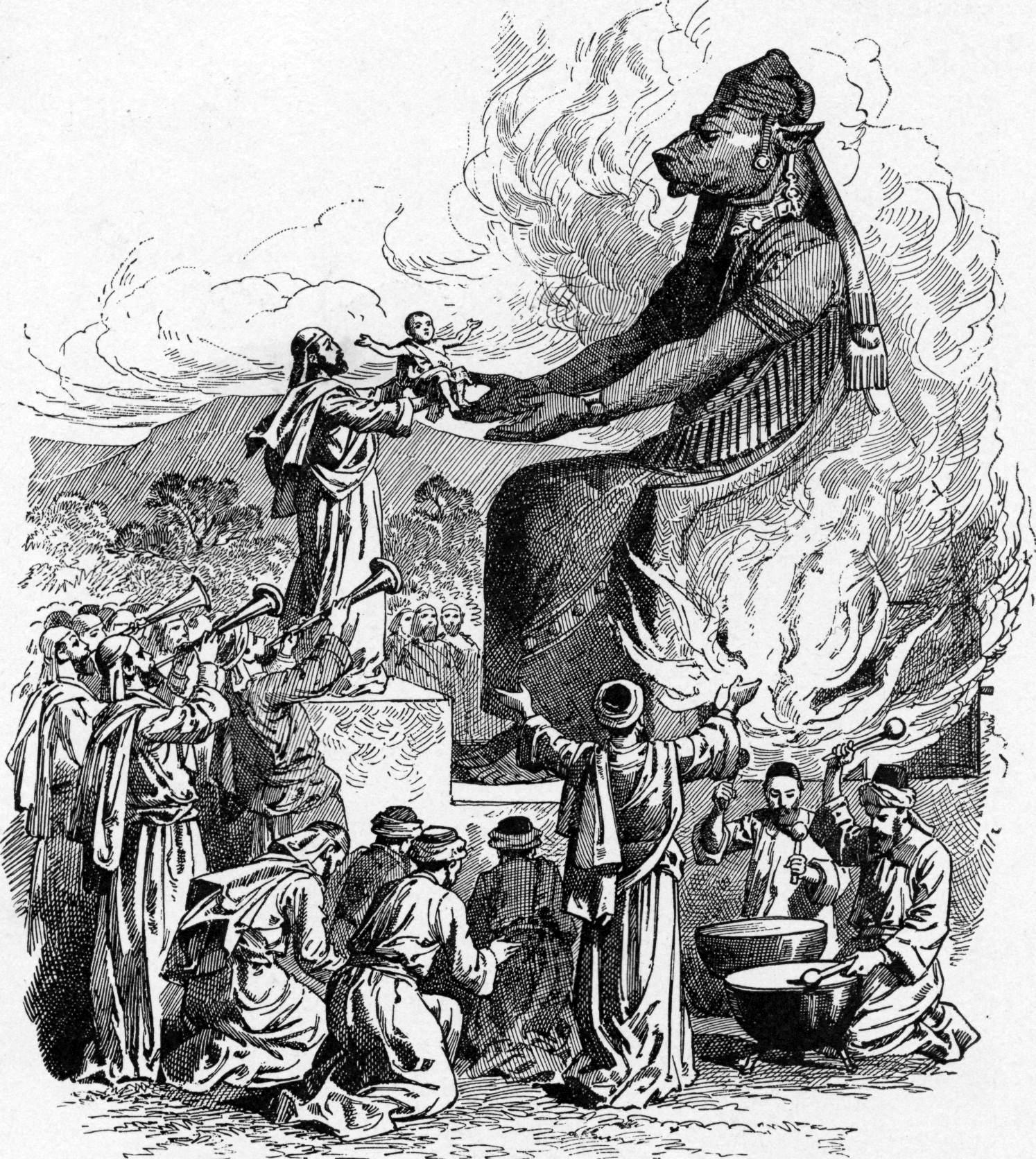

"They also alleged that Kronos had turned against them inasmuch as in former times they had been accustomed to sacrifice to this god the noblest of their sons, but more recently, secretly buying and nurturing children, they had sent these to the sacrifice; and when an investigation was made, some of those who had been sacrificed were discovered to have been substituted by stealth... In their zeal to make amends for the omission, they selected two hundred of the noblest children and sacrificed them publicly; and others who were under suspicion sacrificed themselves voluntarily, in number not less than three hundred. There was in the city a bronze image of Kronos, extending its hands, palms up and sloping towards the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire. It is probable that it was from this that Euripides has drawn the mythical story found in his works about the sacrifice in Tauris, in which he presents Iphigeneia being asked by Orestes: "But what tomb shall receive me when I die? A sacred fire within, and earth's broad rift." Also the story passed down among the Greeks from ancient myth that Cronus did away with his own children appears to have been kept in mind among the Carthaginians through this observance.

Library 20.14

/blockquote>Plutarch Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...:"Again, would it not have been far better for the Carthaginians to have taken Critias or Diagoras to draw up their law-code at the very beginning, and so not to believe in any divine power or god, rather than to offer such sacrifices as they used to offer to Cronos? These were not in the manner that Empedocles describes in his attack on those who sacrifice living creatures: "Changed in form is the son beloved of his father so pious, Who on the altar lays him and slays him. What folly!" No, but with full knowledge and understanding they themselves offered up their own children, and those who had no children would buy little ones from poor people and cut their throats as if they were so many lambs or young birds; meanwhile the mother stood by without a tear or moan; but should she utter a single moan or let fall a single tear, she had to forfeit the money, and her child was sacrificed nevertheless; and the whole area before the statue was filled with a loud noise of flutes and drums so that the cries of wailing should not reach the ears of the people.

Moralia 2, De Superstitione 3

/blockquote>Plato Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...:"With us, for instance, human sacrifice is not legal, but unholy, whereas the Carthaginians perform it as a thing they account holy and legal, and that too when some of them sacrifice even their own sons to Cronos, as I daresay you yourself have heard.

Minos 315c

/blockquote>Theophrastus Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...:"And from then on to the present day they perform human sacrifices with the participation of all, not only in Arcadia during the Lykaia and in Carthage to Kronos, but also periodically, in remembrance of the customary usage, they spill the blood of their own kin on the altars, even though the divine law among them bars from the rites, by means of perirrhanteria and the herald's proclamation, anyone responsible for the shedding of blood in peacetime."Sophocles Sophocles ( 497/496 – winter 406/405 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. was an ancient Greek tragedian known as one of three from whom at least two plays have survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those ...:". . . was chosen as a . . . sacrifice for the city. For from ancient times the barbarians have had a custom of sacrificing human beings to Kronos."Quintus Curtius Rufus Quintus Curtius Rufus (; ) was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alex ...:"Some even proposed renewing a sacrifice which had been discontinued for many years, and which I for my part should believe to be by no means pleasing to the gods, of offering a freeborn boy to Saturn —this sacrilege rather than sacrifice, handed down from their founders, the Carthaginians are said to have performed until the destruction of their city—and unless the elders, in accordance with whose counsel everything was done, had opposed it, the awful superstition would have prevailed over mercy. But necessity, more inventive than any art, introduced not only the usual means of defence, but also some novel ones." History of Alexander IV.III.23Tertullian Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...:"In Africa infants used to be sacrificed to Saturn, and quite openly, down to the proconsulate of Tiberius, who took the priests themselves and on the very trees of their temple, under whose shadow their crimes had been committed, hung them alive like votive offerings on crosses; and the soldiers of my own country are witnesses to it, who served that proconsul in that very task. Yes, and to this day that holy crime persists in secret." Apology 9.2-3Philo of Byblos Philo of Byblos (, ''Phílōn Býblios''; ; – 141), also known as Herennius Philon, was an antiquarian writer of grammatical, lexicon, lexical and historical works in Greek language, Greek. He is chiefly known for his Phoenician history ...:"Among ancient peoples in critically dangerous situations it was customary for the rulers of a city or nation, rather than lose everyone, to provide the dearest of their children as a propitiatory sacrifice to the avenging deities. The children thus given up were slaughtered according to a secret ritual. Now Kronos, whom the Phoenicians call El, who was in their land and who was later divinized after his death as the star of Kronos, had an only son by a local bride named Anobret, and therefore they called him Ieoud. Even now among the Phoenicians the only son is given this name. When war’s gravest dangers gripped the land, Kronos dressed his son in royal attire, prepared an altar and sacrificed him."Lucian Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridi ...:"There is another form of sacrifice here. After putting a garland on the sacrificial animals they hurl them down alive from the gateway and the animals die from the fall. Some even throw their children off the place, but not in the same manner as the animals. Instead, having laid them in a pallet, they drop them down by hand. At the same time they mock them and say that they are oxen, not children."Cleitarchus:"And Kleitarchos says the Phoenicians, and above all the Carthaginians, venerating Kronos, whenever they were eager for a great thing to succeed, made a vow by one of their children. If they would receive the desired things, they would sacrifice it to the god. A bronze Kronos, having been erected by them, stretched out upturned hands over a bronze oven to burn the child. The flame of the burning child reached its body until, the limbs having shriveled up and the smiling mouth appearing to be almost laughing, it would slip into the oven. Therefore the grin is called “sardonic laughter,” since they die laughing."Porphyry:"The Phoenicians too, in great disasters whether of wars or droughts, or plagues, used to sacrifice one of their dearest, dedicating him to Kronos. And the ‘Phoenician History,’ which Sanchuniathon wrote in Phoenician and which Philo of Byblos translated into Greek in eight books, is full of such sacrifices."At Carthage, a large cemetery exists that combines the bodies of both very young children and small animals, and those who assert child sacrifice have argued that if the animals were sacrificed, then so too were the children.Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0009177 Recent archaeology, however, has produced a detailed breakdown of the ages of the buried children and, based on this and especially on the presence of prenatal individuals – that is, still births – it is also argued that this site is consistent with burials of children who had died of natural causes in a society that had a highinfant mortality rate Infant mortality is the death of an infant before the infant's first birthday. The occurrence of infant mortality in a population can be described by the infant mortality rate (IMR), which is the number of deaths of infants under one year of age ..., as Carthage is assumed to have had. That is, the data support the view that Tophets were cemeteries for those who died shortly before or after birth. Conversely, Patricia Smith and colleagues from theHebrew University The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; ) is an Israeli public research university based in Jerusalem. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Chaim Weizmann in July 1918, the public university officially opened on 1 April 1925. It is the second-ol ...andHarvard University Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...show from the teeth and skeletal analysis at the Carthage Tophet that infant ages at death (about two months) do not correlate with the expected ages of natural mortality (perinatal), apparently supporting the child sacrifice thesis. Greek, Roman and Israelite writers refer to Phoenician child sacrifice. Skeptics suggest that the bodies of children found in Carthaginian and Phoenician cemeteries were merely the cremated remains of children that died naturally. Sergio Ribichini has argued that the Tophet was "a child necropolis designed to receive the remains of infants who had died prematurely of sickness or other natural causes, and who for this reason were "offered" to specific deities and buried in a place different from the one reserved for the ordinary dead". According to Stager and Wolff, in 1984, there was a consensus among scholars that Carthaginian children were sacrificed by their parents, who would make a vow to kill the next child if the gods would grant them a favor: for instance that their shipment of goods was to arrive safely in a foreign port.

Europe

Archaeologist Peter Warren was involved in theBritish School at Athens The British School at Athens (BSA; ) is an institute for advanced research, one of the eight British International Research Institutes supported by the British Academy, that promotes the study of Greece in all its aspects. Under UK law it is a reg ...excavation ofPalekastro Palaikastro or Palekastro (, officially ), with the Godart and Olivier abbreviation PK, is a thriving town, geographic heir to a long line of settlements extending back into prehistoric times, at the east end of the Mediterranean island Crete. T ...for one season and the excavation atLefkandi Lefkandi () is a coastal village on the island of Euboea, Greece. Archaeological finds attest to a settlement on the promontory locally known as Xeropolis, while several associated cemeteries have been identified nearby. The settlement site is loc ...for two seasons. Then he led the excavation at Fournou Korifi, Myrtos from 1967 to 1968. During the 1980s, in two archaeology magazines, Warren wrote about "child sacrifice" despite there being no mention of this subject in the official excavation report, which was completed and published along with his book in 1972. Rodney Castleden uncovered a sanctuary near Knossos where the remains of a 17-year-old were found. The Ver Sacrum is a religious practice of ancient Italic peoples, especially theSabelli Sabellians is a collective ethnonym An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or en ...(orSabini The Sabines (, , , ; ) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains (see Sabina) of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome. The Sabines divided into ...) and their offshootSamnites The Samnites () were an ancient Italic peoples, Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy. An Oscan language, Oscan-speaking Osci, people, who originated as an offsh .... The practice is related to that of ''devotio In ancient Roman religion, the ''devotio'' was an extreme form of '' votum'' in which a Roman general vowed to sacrifice his own life in battle along with the enemy to chthonic gods in exchange for a victory. The most extended description of t ...'' inRoman religion Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule. The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, .... It was customary to resort to it at times of particular danger or strife for the community. Some scholars believe that in earlier times ''devoted'' or vowed children were actually sacrificed, but later expulsion was substituted.Dionysius of Halicarnassus Dionysius of Halicarnassus (, ; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary style was ''atticistic'' – imitating Classical Attic Greek in its prime. ...states the practice of child sacrifice was one of the causes that brought about the fall of thePelasgians The name Pelasgians (, ) was used by Classical Greek writers to refer either to the predecessors of the Greeks, or to all the inhabitants of Greece before the emergence of the Greeks. In general, "Pelasgian" has come to mean more broadly all ...in Italy. The human children who had been ''devoted'' were required to leave the community in early adulthood, at 20 or 21 years of age. They were entrusted to a god for protection, and led to the border with a veiled face. Often they were led by an animal under the auspices of the god. As a group, the youth were called ''sacrani'' and were supposed to enjoy the protection of Mars until they had reached their destination, expelled the inhabitants or forced them into submission, and founded their own settlement. TheWaldensians The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ..., a medieval sect deemed heretical, were accused of participating in child sacrifice.

Africa

Canary Islands

In the heart of the ancientGuanche Guanche may refer to: *Guanches, the indigenous people of the Canary Islands *Guanche language, an extinct language, spoken by the Guanches until the 16th or 17th century *''Conus guanche ''Conus guanche'' is a species of sea snail, a marine ga ...culture, inTenerife Tenerife ( ; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands, an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. With a land area of and a population of 965,575 inhabitants as of A ...it was the custom to throw a living child from the ''Punta de Rasca'' at sunrise at the summer solstice. Sometimes these children came from all parts of the island, even from remote areas of ''Punta de Rasca''. It follows that it was a common custom of the island. On this island sacrificing other human victims associated with the death of the king, where adult men rushed to the sea are also known. Embalmers who produced the Guanche mummies also had a habit of throwing themselves into the sea one year after the king's death.Sacrificios entre los Aborígenes canarios

/ref> Bones of children mixed with lambs and kids were found inGran Canaria Gran Canaria (, ; ), also Grand Canary Island, is the third-largest and second-most-populous island of the Canary Islands, a Spain, Spanish archipelago off the Atlantic coast of Northwest Africa. the island had a population of that constitut ..., and in Tenerife amphorae have been found with remains of children inside. This suggests a different kind of ritual infanticide than those who were thrown overboard.

South Africa

The continued murder within Black communities of children of all ages, for body parts with which to make muti, for purposes of witchcraft, still occurs in South Africa. Muti murders occur throughout South Africa, especially in rural areas. Traditional healers or witch doctors often grind up body parts and combine them with roots, herbs, seawater, animal parts, and other ingredients to prepare potions and spells for their clients.

Uganda

In the early 21st century Uganda has experienced a revival of child sacrifice. In spite of government attempts to downplay the issue, an investigation by theBBC The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...into human sacrifice inUganda Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...found that ritual killings of children are more common than Ugandan authorities admit. There are many indicators that politicians and politically connected wealthy businessmen are involved in sacrificing children in practice of traditional religion, which has become a commercial enterprise.Rogers, Chris 2011. Where child sacrifice is a business, BBC News Africa (11 October): https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-15255357#story_continues_1

See also

* Child cannibalism * Early infanticidal childrearing *Human sacrifice Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...*Infanticide Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of re ...* Religious abuse *Religious violence Religious violence covers phenomena in which religion is either the target or perpetrator of violent behavior. All the religions of the world contain narratives, symbols, and metaphors of violence and war and also nonviolence and peacemaking. ...

Notes

References

External links

* {{Commons category-inline

11/04/2008 Child survives sacrifice in Uganda ''UGPulse.com''

Religion and violence Gehenna Crimes involving Satanism or the occult