Chien Shiung Wu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chien-Shiung Wu ( zh, t=吳健雄, p=Wú Jiànxióng, w=Wu2 Chien4-Hsiung2; May 31, 1912 – February 16, 1997) was a Chinese-American

Wu and Dong Ruo-Fen arrived in

Wu and Dong Ruo-Fen arrived in

In September 1944, Wu was contacted by the Manhattan District Engineer,

In September 1944, Wu was contacted by the Manhattan District Engineer,

After the second world war, communication with China was restored, and Wu received a letter from her family, but plans to visit China were disrupted by the

After the second world war, communication with China was restored, and Wu received a letter from her family, but plans to visit China were disrupted by the

In her post-war research, Wu, now an established physicist, continued to investigate beta decay.

In her post-war research, Wu, now an established physicist, continued to investigate beta decay.

Wu would spend most of her time in her later years visiting the

Wu would spend most of her time in her later years visiting the

* Elected a fellow of the

* Elected a fellow of the

Wu Chien-Shiung Education Foundation

(Columbia University)

The Fall of Parity Photo Gallery with Short Biographies

NIST *

Optional view: large-scale black & white photo

from the above

Wu, Chien-Shiung

National Women's Hall of Fame

E-Book: Madame Wu Chien-Shiung

Chien-Shiung Wu

Atomic Heritage Foundation Profile

Medal of Science: Wu Chien-Shiung

Confidence and Crises in the Second World War: Chien-Shiung Wu

Legendary Scientists: Chien-Shiung Wu

Chien-Shiung Wu, Notable Chinese-American Scientist

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wu, Chien-Shiung Chien-Shiung Wu, 1912 births 1997 deaths American nuclear physicists American women physicists Burials in Suzhou Chinese emigrants to the United States Chinese nuclear physicists Chinese women physicists Chinese physicists Columbia University faculty Educators from Suzhou Fellows of the American Physical Society Foreign members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Manhattan Project people Members of Academia Sinica Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Nanjing University alumni National Central University alumni National Medal of Science laureates People from Taicang Physicists from Jiangsu Princeton University faculty Rare earth scientists Scientists from Suzhou American scientists of Asian descent Smith College faculty University of California, Berkeley alumni Wolf Prize in Physics laureates Women nuclear physicists Writers from Suzhou Academic staff of Zhejiang University 20th-century Chinese women scientists 20th-century Chinese scientists 20th-century American physicists American women academics 20th-century American women Women on the Manhattan Project Presidents of the American Physical Society Graduate Women in Science members

particle

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

and experimental physicist

Experimental physics is the category of disciplines and sub-disciplines in the field of physics that are concerned with the observation of physical phenomena and experiments. Methods vary from discipline to discipline, from simple experiments and o ...

who made significant contributions in the fields of nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

and particle physics. Wu worked on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, where she helped develop the process for separating uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

into uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

and uranium-238

Uranium-238 ( or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However, it i ...

isotopes by gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology that was used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through microporous membranes. This produces a slight separation (enrichment factor 1.0043) between the molecules containi ...

. She is best known for conducting the Wu experiment

The Wu experiment was a particle physics, particle and nuclear physics experiment conducted in 1956 by the Chinese American physicist Chien-Shiung Wu in collaboration with the Low Temperature Group of the US National Bureau of Standards. The expe ...

, which proved that parity is not conserved. This discovery resulted in her colleagues Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang winning the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

, while Wu herself was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize in Physics

The Wolf Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Wolf Foundation in Israel. It is one of the six Wolf Prizes established by the Foundation and awarded since 1978; the others are in Agriculture, Chemistry, Mathematics, Medicine and Arts.

The ...

in 1978. Her expertise in experimental physics

Experimental physics is the category of disciplines and sub-disciplines in the field of physics that are concerned with the observation of physical phenomena and experiments. Methods vary from discipline to discipline, from simple experiments and o ...

evoked comparisons to Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

. Her nicknames include the "First Lady of Physics", the "Chinese Marie Curie" and the "Queen of Nuclear Research".

Early life

Chien-Shiung Wu was born in the town of Liuhe, Taicang inJiangsu

Jiangsu is a coastal Provinces of the People's Republic of China, province in East China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with its capital in Nanjing. Jiangsu is the List of Chinese administra ...

province, China, on May 31, 1912, the second of three children of Wu Zhong-Yi ( zh, t=吳仲裔 , labels=no) and Fan Fu-Hua ( zh, t=樊復華, labels=no). The family custom was that children of this generation had Chien as the first character (generation name

A generation name (variously zibei or banci in Chinese; tự bối, ban thứ or tên thế hệ in Vietnamese; hangnyeolja in Korea) is one of the characters in a traditional Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean given name, and is so called becau ...

) of their forename, followed by the characters in the phrase Ying-Shiung-Hao-Jie, which means "heroes and outstanding figures". Accordingly, she had an older brother, Chien-Ying, and a younger brother, Chien-Hao. Wu and her father were extremely close, and he encouraged her interests passionately, creating an environment where she was surrounded by books, magazines, and newspapers. Wu's mother was a teacher and valued education for both sexes. Zhongyi Wu, her father, was an engineer and a social progressive. He participated in the 1913 Second Revolution while in Shanghai and moved to Liuhe after its failure. Zhongyi became a local leader. He created a militia that destroyed local bandits. He also established the Ming De School for girls with himself as principal.

Education

Wu receivedprimary education

Primary education is the first stage of Education, formal education, coming after preschool/kindergarten and before secondary education. Primary education takes place in ''primary schools'', ''elementary schools'', or first schools and middle s ...

at the Ming De School. Wu grew up as a modest and inquisitive child in a well-to-do family. She did not play outside like the other children but instead would listen to the newly invented radio for pleasure and knowledge. She also enjoyed poetry and Chinese classics such as the Analects

The ''Analects'', also known as the ''Sayings of Confucius'', is an ancient Chinese philosophical text composed of sayings and ideas attributed to Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled by his followers. ...

, and western literature on democracy that her father promoted at home. Wu would listen to her father recite paragraphs from scientific journals instead of children's stories until Wu learned how to read.

Wu left her hometown in 1923 at the age of 11 to go to the Suzhou

Suzhou is a major prefecture-level city in southern Jiangsu province, China. As part of the Yangtze Delta megalopolis, it is a major economic center and focal point of trade and commerce.

Founded in 514 BC, Suzhou rapidly grew in size by the ...

Women's Normal School No. 2, which was from her home. This was a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

with classes for teacher training as well as for regular high school, and it introduced subjects in science that slowly became a growing passion for the young Wu. Admission to teacher training was more competitive, as it did not charge for tuition or board and guaranteed a job on graduation. Although her family could have afforded to pay, Wu chose the more competitive option and was ranked ninth among around 10,000 applicants.

In 1929, Wu graduated at the top of her class and was admitted to National Central University in Nanjing

Nanjing or Nanking is the capital of Jiangsu, a province in East China. The city, which is located in the southwestern corner of the province, has 11 districts, an administrative area of , and a population of 9,423,400.

Situated in the Yang ...

. According to government regulations of the time, teacher-training college students wanting to move on to universities needed to serve as schoolteachers for one year. In Wu's case, this was only nominally enforced. She went to teach at a public school in Shanghai, the president of which was the famous philosopher Hu Shih

Hu Shih ( zh, t=胡適; 17 December 189124 February 1962) was a Chinese academic, writer, and politician. Hu contributed to Chinese liberalism and language reform, and was a leading advocate for the use of written vernacular Chinese. He part ...

. Hu became a very notable political icon whom Wu saw as a second father and would visit Wu when she was in the United States. Hu was previously Wu's teacher when she took a few courses at National China College and was impressed when Wu, who sat in the front seat to be noticed by her hero, finished and perfected the first three-hour assessment in less than two hours. Her elders advised her to "ignore the obstacles." This was similar to what her father always reiterated to her, "Just put your head down and keep walking forward."

Although Wu ended up doing scientific research, her writing was considered outstanding thanks to her early training. Her Chinese calligraphy was praised by others. Before matriculating to National Central University Wu spent the summer preparing for her studies with her usual full force. She felt that her background and training in Suzhou Women's Normal School were insufficient to prepare her for majoring in science. Her father encouraged her to plunge ahead, and bought her three books for her self-study that summer: trigonometry, algebra, and geometry. This experience was the beginning of her habit of self-study, and it gave her sufficient confidence to major in mathematics in the fall of 1930.

From 1930 to 1934, Wu studied at National Central University (now known as Nanjing University

Nanjing University (NJU) is a public university in Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. It is affiliated and sponsored by the Ministry of Education. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First-Class Construction. The univers ...

) and first majored in mathematics but later transferred to physics. She became involved in student politics. Relations between China and Japan were tense at this time, and students were urging the government to take a stronger line with Japan. Wu was elected as one of the student leaders by her colleagues because they felt that since she was one of the top students at the university, her involvement would be forgiven, or at least overlooked, by the authorities. That being the case, she was careful not to neglect her studies. She led protests that included a sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

at the Presidential Palace in Nanjing, where the students were met by Chiang Kai-shek.

For two years after graduation, she did graduate-level study in physics and worked as an assistant at Zhejiang University

Zhejiang University (ZJU) is a public university, public research university in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China. It is affiliated with the Ministry of Education (China), Ministry of Education. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and D ...

. She became a researcher at the Institute of Physics of the Academia Sinica

Academia Sinica (AS, ; zh, t=中央研究院) is the national academy of the Taiwan, Republic of China. It is headquartered in Nangang District, Taipei, Nangang, Taipei.

Founded in Nanjing, the academy supports research activities in mathemat ...

. Her supervisor was Gu Jing-Wei, a female professor who had earned her PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

abroad at the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

and encouraged Wu to do the same. She became an important role model to the young Wu, who developed confidence and was sometimes blunt and honest when giving advice to close friends. Wu was accepted by the University of Michigan, and her uncle, Wu Zhou-Zhi, provided the necessary funds. She embarked for the United States with a female friend and chemist from Taicang, Dong Ruo-Fen ( zh, c=董若芬 , labels=no), on the in August 1936. Her parents and uncle saw her off at the Huangpu Bund as she boarded the ship. Her father and uncle were very sad while her mother was in tears that day, and little did Wu know that she would never see her parents again. Though her family would survive the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, she would only visit the remaining members of her family decades later when she made trips to China in the 1970s.

Early physics career

Berkeley

Wu and Dong Ruo-Fen arrived in

Wu and Dong Ruo-Fen arrived in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, where Wu's plans for graduate study changed after visiting the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

. She met physicist Luke Chia-Liu Yuan, a middle-class grandson from the concubine of Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 18596 June 1916) was a Chinese general and statesman who served as the second provisional president and the first official president of the Republic of China, head of the Beiyang government from 1912 to 1916 and ...

(the self-proclaimed president of the new Republic of China and Emperor of China for six months before his death). As a result of his political lineage, Luke did not talk much about Yuan Shikai and Wu would tease him after she discovered the truth since her father once rebelled against Yuan Shikai. Yuan showed her the Radiation Laboratory, where the director was Ernest O. Lawrence, who would soon win the Nobel Prize for Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prize, Nobel Prizes establi ...

in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental ...

.

Wu was shocked at the sexism in American society when she learned that at Michigan women were not even allowed to use the front entrance, and decided that she would prefer to study at the more liberal Berkeley in California. Wu was also influenced by her interest in the Berkeley facilities which included the first cyclotron of Lawrence, but her decision would disappoint Dong who studied at Michigan on her own. Yuan took her to see Raymond T. Birge, the head of the physics department, and he offered Wu a place in the graduate school despite the fact that the academic year had already commenced. Wu abandoned her plans to study at Michigan and enrolled at Berkeley. Her Berkeley classmates included Robert R. Wilson, who like others secretly admired Wu, and George Volkoff; her closest friends included post-doctoral student Margaret Lewis and Ursula Schaefer, a history student who chose to remain in the United States rather than return to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

Wu missed Chinese cuisine and was not impressed with the food at Berkeley, so she always dined with friends such as Schaeffer at her favorite restaurant, the Tea Garden. Wu and her friends would get free meals that were not part of the menu due to her friendship with the owner. Wu applied for a scholarship at the end of her first year, but there was prejudice against Asian students from the department head Birge, and Wu and Yuan were instead offered a readership with a lower stipend. Yuan then applied for, and secured, a scholarship at Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private university, private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small g ...

. Birge, however, respected Wu for her talents and was the reason Wu could enroll even though the academic year already started.

Wu made rapid progress in her education and her research. Although Lawrence was officially her supervisor, she also worked closely with the famous Italian physicist Emilio Segrè. She quickly became his favorite student and the two conducted studies on beta decay, including xenon, which would provide important results in the future of nuclear bombs. According to Segrè, Wu was a popular student who was talented. In his autobiography, Nobel laureate Luis Alvarez said of Wu, I got to know this graduate student in this idle time. She used the same room next door, and was called "Gee Gee" u's nickname at Berkeley She was the most talented and most beautiful experimental physicist I have ever met.Segrè recognized Wu's brilliance and compared her to Wu's heroine

Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

, whom Wu always quoted, but said that Wu was more "worldly, elegant, and witty." Meanwhile, Lawrence described Wu as "the most talented female experimental physicist he had ever known, and that she would make any laboratory shine." When it came time to present her thesis in 1940, it had two separate parts presented in very neat fashion. The first was on bremsstrahlung

In particle physics, bremsstrahlung (; ; ) is electromagnetic radiation produced by the deceleration of a charged particle when deflected by another charged particle, typically an electron by an atomic nucleus. The moving particle loses kinetic ...

, the electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength ...

produced by the deceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnit ...

of a charged particle when deflected by another charged particle, typically an electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

by an atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford at the Department_of_Physics_and_Astronomy,_University_of_Manchester , University of Manchester ...

, with the latter being on radioactive Xe. She investigated the first study using beta-emitting phosphorus-32

Phosphorus-32 (32P) is a radioactive isotope of phosphorus. The nucleus of phosphorus-32 contains 15 protons and 17 neutrons, one more neutron than the most common isotope of phosphorus, phosphorus-31. Phosphorus-32 only exists in small quantiti ...

, a radioactive isotope easily produced in the cyclotron that Lawrence and his brother John H. Lawrence were evaluating for use in cancer treatment and as a radioactive tracer

A radioactive tracer, radiotracer, or radioactive label is a synthetic derivative of a natural compound in which one or more atoms have been replaced by a radionuclide (a radioactive atom). By virtue of its radioactive decay, it can be used to ...

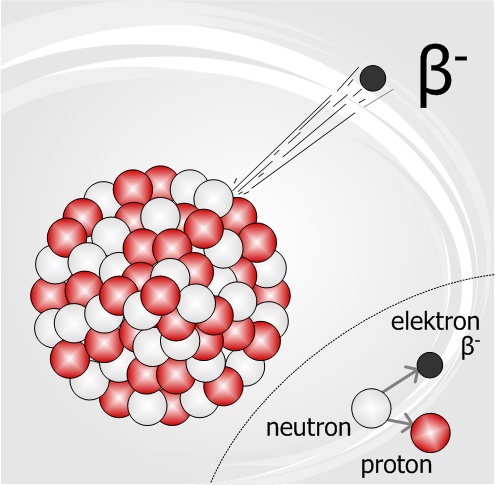

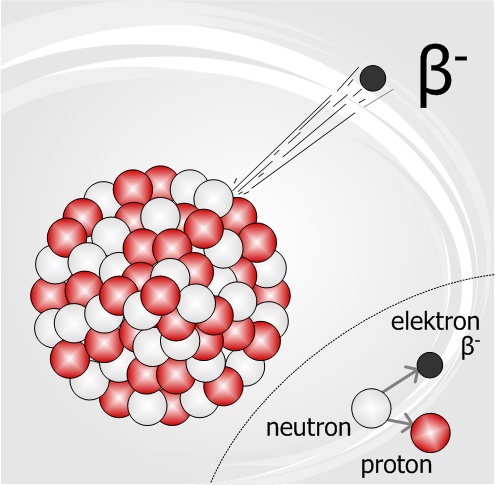

. This marked Wu's first work with beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

, a subject on which she would become an authority.

The second part of the thesis was about the production of radioactive isotopes of Xe produced by the nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

with the 37-inch and 60-inch cyclotrons at the Radiation Laboratory. Her second part on Xe and nuclear fission so impressed her committee, which featured Lawrence and J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World ...

, whom Wu affectionately called, "Oppie", that Oppenheimer believed that Wu knew everything about the absorption cross section of neutrons, a concept that would be applied when Wu joined the Manhattan Project.

Wu completed her PhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

in June 1940, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

, the US academic honor society. In spite of Lawrence and Segrè's recommendations, she could not secure a faculty position at a university, so she remained at the Radiation Laboratory as a post-doctoral fellow. Because of her early achievements, the ''Oakland Tribune

The ''Oakland Tribune'' was a daily newspaper published in Oakland, California, and a predecessor of the '' East Bay Times''. It was published by the Bay Area News Group (BANG), a subsidiary of MediaNews Group. Founded in 1874, the ''Tribune'' ...

'' released an issue on her entitled "Outstanding Research in Nuclear Bombardments by a Petite Chinese Lady". The report quipped, A petite Chinese girl worked side by side with some top US scientists in the laboratory studying nuclear collisions. This girl is the new member of the Berkeley physics research team. Ms. Wu, or more appropriately Dr. Wu, looks as though she might be an actress or an artist or a daughter of wealth in search of Occidental culture. She could be quiet and shy in front of strangers, but very confident and alert in front of physicists and graduate students. China is always on her mind. She was so passionate and excited whenever "China" and "democracy" were referred to, as democracy meant so much in the 1940s. She is preparing to return and contribute to the rebuilding of China.Her plans changed when the Second World War began.

World War II and the Manhattan Project

Wu and Yuan were married at the home ofRobert Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan ( ; March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923 "for his work on the elementary charge of electricity and on the photoelectric effect".

Millikan gradua ...

, Yuan's academic supervisor and the President of Caltech, on May 30, 1942. Neither the bride's nor the groom's families were able to attend due to the outbreak of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

. Wu and Yuan moved to the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

, where Wu became an assistant professor at Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts, United States. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smit ...

, a private women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence, Massachusetts, Florence and ...

, while Yuan worked on radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

for RCA

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

. She found the job frustrating, as her duties involved teaching only, and there was no opportunity for research. She appealed to Lawrence, who wrote letters of recommendation to a number of universities. Smith responded by making Wu an associate professor and increasing her salary. She accepted a job from Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

as the first female faculty member in the history of the physics department, where she taught officers of the navy.

In March 1944, Wu joined the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

's Substitute Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

. She lived in a dormitory there, returning to Princeton on the weekends. The role of the SAM Laboratories, headed by Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the ...

, was to support the Manhattan Project's gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology that was used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through microporous membranes. This produces a slight separation (enrichment factor 1.0043) between the molecules containi ...

( K-25) program for uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

. Wu worked alongside James Rainwater in a group led by William W. Havens Jr., whose task was to develop radiation detector instrumentation.

In September 1944, Wu was contacted by the Manhattan District Engineer,

In September 1944, Wu was contacted by the Manhattan District Engineer, Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Kenneth Nichols. Wu was frustrated with her lack of professorships and volunteered to help out in the project. In the beginning, Wu was assigned to check the radiation effect of the reactor by building her own instruments; later, however, she was contacted for a much bigger role. The newly commissioned B Reactor

The B Reactor at the Hanford Site, near Richland, Washington, was the first large-scale nuclear reactor ever built, at 250 MW. It achieved criticality on September 26, 1944. The project was a key part of the Manhattan Project, the United States ...

, the first practical nuclear reactor ever built, which was located at the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It has also been known as SiteW and the Hanford Nuclear R ...

had run into an unexpected problem, starting up and shutting down at regular intervals. John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr to e ...

and partner Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

suspected that a fission product

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the releas ...

, Xe-135, with a half-life Half-life is a mathematical and scientific description of exponential or gradual decay.

Half-life, half life or halflife may also refer to:

Film

* Half-Life (film), ''Half-Life'' (film), a 2008 independent film by Jennifer Phang

* ''Half Life: ...

of 9.4 hours, was the culprit, and might be a neutron poison

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison (also called a neutron absorber or a nuclear poison) is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable ef ...

or absorber. Segrè then remembered the 1940 PhD thesis that Wu had done for him at Berkeley on the radioactive isotopes of Xe and told Fermi to "ask Ms. Wu". The paper on the subject was still unpublished, but after Fermi contacted Wu, Segrè visited her dorm room together with Nichols and collected the typewritten draft prepared for the ''Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The journal was established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the Ame ...

''. The suspicions of Fermi and Wheeler came true, Wu's paper unknowingly verified that Xe-135 was indeed the culprit for the B Reactor; it turned out to have an unexpectedly large neutron absorption cross-section. Wu, wary of her publication giving information to other nations on the arms race of the war, waited for a few months before November 1944, when she and Segrè submitted a complete study on these results, which was published months before the bombs were used the next year.

Wu also used her findings in radioactive uranium separation to build the standard model for producing enriched uranium to fuel the atomic bombs at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's po ...

facility as well as build innovative Geiger counter

A Geiger counter (, ; also known as a Geiger–Müller counter or G-M counter) is an electronic instrument for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation with the use of a Geiger–Müller tube. It is widely used in applications such as radiat ...

s. Like many involved physicists in their later years, Wu later distanced herself from the Manhattan Project due to its destructive outcome and recommended to the Taiwanese president Chiang Kai-shek in 1962 to never build nuclear weapons. However, she was pleased to know that her family was safe in China. Years later, Wu in a rare occasion opened up on her involvement in building the bomb,Do you think that people are so stupid and self-destructive? No. I have confidence in humankind. I believe we will one day live together peacefully.

Famous early experiments and academic leading career

After the end of the war in August 1945, Wu accepted an offer of a position as an associateresearch professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a 'person who professes'. Professors ...

at Columbia. She would remain at Columbia for the rest of her career, and was first named associate professor

Associate professor is an academic title with two principal meanings: in the North American system and that of the ''Commonwealth system''.

In the ''North American system'', used in the United States and many other countries, it is a position ...

in 1952, which made her the first woman to become a tenured physics professor in university history.

In November 1949, Wu experimented with the conclusions of Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) thought experiment, which called quantum entanglement

Quantum entanglement is the phenomenon where the quantum state of each Subatomic particle, particle in a group cannot be described independently of the state of the others, even when the particles are separated by a large distance. The topic o ...

"spooky action at a distance". Wu was the first to establish the phenomenon and validity of entanglement using photons through observing angular correlation, as her result confirmed Maurice Pryce and John Clive Ward's calculations on the correlation of the quantum polarizations of two photons propagating in opposite directions. Specifically, the experiment carried out by Wu was the first important confirmation of quantum results relevant to a pair of entangled photons as applicable to the EPR paradox.

In the 1970s, she carried out one the first Bell test

A Bell test, also known as Bell inequality test or Bell experiment, is a real-world physics experiment designed to test the theory of quantum mechanics in relation to Albert Einstein's concept of local realism. Named for John Stewart Bell, the exp ...

s to confirm that quantum mechanics violates Bell's inequalities.

Chinese civil war and permanent residency

After the second world war, communication with China was restored, and Wu received a letter from her family, but plans to visit China were disrupted by the

After the second world war, communication with China was restored, and Wu received a letter from her family, but plans to visit China were disrupted by the civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Due to the civil war and communist takeover led by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, Wu would not return to China until decades later to meet her surviving uncle and younger brother. Though Wu did not support Mao, she also did not particularly respect the now deposed president Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Mei-ling

Soong Mei-ling (also spelled Soong May-ling; March 4, 1898 – October 23, 2003), also known as Madame Chiang (), was a Chinese political figure and socialite. The youngest of the Soong sisters, she married Chiang Kai-shek and played a prom ...

. Wu found Soong to be class-conscious, while Chiang, now based on Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, was too complacent with foreign affairs and willing to let Soong handle diplomatic issues for him. However she decided to lend a bit more support to the Republic of China or Taiwan, as her teacher Hu carried close ties with the old republic. Due to the war, many were displaced and younger students would leave for the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, while scholars in America could not return home. She missed China deeply, and would often go with Luke to buy fabric to make her own qipao

''Cheongsam'' (, ), also known as the ''qipao'' () and sometimes referred to as the mandarin gown, is a Chinese dress worn by women which takes inspiration from the , the ethnic clothing of the Manchu people. The cheongsam is most often see ...

, which she always wore under her lab coat as a way to remember the country.

Wu was also busy due to the birth of her son, Vincent ( zh, t=袁緯承 , labels=no ''Yuán Wěichéng''), in 1947. Vincent became a physicist like his parents and attended Columbia, following in Wu's footsteps. By the end of the civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

in 1949, Yuan joined the Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratories, United States Department of Energy national laboratory located in Upton, New York, a hamlet of the Brookhaven, New York, Town of Brookhaven. It w ...

, and the family bought another home in Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

. Yuan would regularly travel to Brookhaven in Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

, and on weekends return to the family's Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

home near Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

where Wu worked as its first female physics professor. After the communists came to power in China that year, Wu's father wrote urging her not to return. Since her passport had been issued by the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

government, she found it difficult to travel abroad as places such as Switzerland did not recognize her passport. Sometimes her friend in Switzerland, physicist Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli ( ; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and a pioneer of quantum mechanics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics "for the ...

, had to secure her special visas just to enter the country. This eventually led to her decision to stay in the United States. With the help of Columbia chairman Charles H. Townes, Wu would become a US citizen in 1954.

Establishing beta decay

In her post-war research, Wu, now an established physicist, continued to investigate beta decay.

In her post-war research, Wu, now an established physicist, continued to investigate beta decay. Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

had published his theory of beta decay in 1934, but an experiment by Luis Walter Alvarez

Luis Walter Alvarez (June 13, 1911 – September 1, 1988) was an American experimental physicist, inventor, and professor who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968 for his discovery of resonance (particle physics), resonance states in ...

had produced results at variance with the theory. Wu set out to repeat the experiment and verify the result. Wu was already heavily invested in working on beta decay as she took on the subject at UC Berkeley. In the year 1949, Wu completely established Fermi's theory and showed how beta decay worked, especially in creating electrons, neutrinos, and positrons. Supposedly, most of the electrons should come out of the nucleus at high speeds.

After careful research, Wu suspected that the problem was that a thick and uneven film of copper(II) sulfate

Copper(II) sulfate is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It forms hydrates , where ''n'' can range from 1 to 7. The pentahydrate (''n'' = 5), a bright blue crystal, is the most commonly encountered hydrate of copper(II) sulfate, whi ...

() was being used as a copper-64

Copper-64 (Cu) is a positron and beta emitting isotope of copper, with applications for molecular radiotherapy and positron emission tomography. Its unusually long half-life (12.7-hours) for a positron-emitting isotope makes it increasingly usef ...

beta ray source, which was causing the emitted electrons to lose energy. To get around this, she adapted an older form of the spectrometer

A spectrometer () is a scientific instrument used to separate and measure Spectrum, spectral components of a physical phenomenon. Spectrometer is a broad term often used to describe instruments that measure a continuous variable of a phenomeno ...

, a solenoidal spectrometer. She added detergent to the copper sulfate Copper sulfate may refer to:

* Copper(II) sulfate, CuSO4, a common, greenish blue compound used as a fungicide and herbicide

* Copper(I) sulfate, Cu2SO4, an unstable white solid which is uncommonly used

{{chemistry index

Copper compounds ...

to produce a thin, even film. She then demonstrated that the discrepancies observed were the result of experimental error; her results were consistent with Fermi's theory. The speeds of the electrons that were commonly produced in experiments were now shown to be significantly slower. Thus by analyzing radioactive materials used by previous researchers, she proved that this was the cause of the problem and not from theoretical flaws. Wu thus established herself as the leading physicist on beta decay. Her work on beta decay became hugely beneficial to her later research and to modern physics in general.

Parity experiment

At Columbia, Wu knew the Chinese-born theoretical physicist Tsung-Dao Lee personally. In the mid-1950s, Lee and another Chinese theoretical physicist,Chen Ning Yang

Yang Chen-Ning or Chen-Ning Yang (; born 1 October 1922), also known as C. N. Yang or by the English name Frank Yang, is a Chinese theoretical physicist who made significant contributions to statistical mechanics, integrable systems, gauge th ...

, grew to question a hypothetical law of elementary particle

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. The Standard Model presently recognizes seventeen distinct particles—twelve fermions and five bosons. As a c ...

physics, the "law of conservation of parity". One example highlighting the problem was the puzzle of the theta and tau particles, two apparently differently charged, strange meson

In particle physics, a meson () is a type of hadronic subatomic particle composed of an equal number of quarks and antiquarks, usually one of each, bound together by the strong interaction. Because mesons are composed of quark subparticles, the ...

s. They were so similar that they would ordinarily be considered to be the same particle, but different decay modes resulting in two different parity states were observed, suggesting that and were different particles, if parity is conserved:

:

Lee and Yang's research into existing experimental results convinced them that parity was conserved for electromagnetic

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

interactions and for the strong interaction

In nuclear physics and particle physics, the strong interaction, also called the strong force or strong nuclear force, is one of the four known fundamental interaction, fundamental interactions. It confines Quark, quarks into proton, protons, n ...

. For this reason, scientists had expected that it would also be true for the weak interaction

In nuclear physics and particle physics, the weak interaction, weak force or the weak nuclear force, is one of the four known fundamental interactions, with the others being electromagnetism, the strong interaction, and gravitation. It is th ...

, but it had not been tested, and Lee and Yang's theoretical studies showed that it might not hold true for the weak interaction. Lee and Yang worked out a pencil-and-paper design of an experiment for testing conservation of parity in the laboratory. Because of her expertise in choosing and then working out the hardware manufacture, set-up, and laboratory procedures, Wu then informed Lee that she could carry out the experiment

''The Experiment'' is a 2002 BBC documentary series in which 15 men are randomly selected to be either "prisoner" or guard, contained in a simulated prison over an eight-day period. Produced by Steve Reicher and Alex Haslam, it presents the fi ...

.

Wu chose to do this by taking a sample of radioactive cobalt-60

Cobalt-60 (Co) is a synthetic radioactive isotope of cobalt with a half-life of 5.2714 years. It is produced artificially in nuclear reactors. Deliberate industrial production depends on neutron activation of bulk samples of the monoisotop ...

and cooling it to cryogenic

In physics, cryogenics is the production and behaviour of materials at very low temperatures.

The 13th International Institute of Refrigeration's (IIR) International Congress of Refrigeration (held in Washington, DC in 1971) endorsed a univers ...

temperatures with liquid gases. Cobalt-60 is an isotope that decays by beta particle

A beta particle, also called beta ray or beta radiation (symbol β), is a high-energy, high-speed electron or positron emitted by the radioactive decay of an atomic nucleus, known as beta decay. There are two forms of beta decay, β− decay and � ...

emission, and Wu was also an expert on beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

. The extremely low temperatures were needed to reduce the amount of thermal vibration of the cobalt atoms to almost zero. Also, Wu needed to apply a constant and uniform magnetic field across the sample of cobalt-60 in order to cause the spin axes of the atomic nuclei

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. Aft ...

to line up in the same direction. For this cryogenic work, she needed the facilities of the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sc ...

and its expertise in working with liquid gases, and traveled to its headquarters in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

with her equipment to carry out the experiments.

Lee and Yang's theoretical calculations predicted that the beta particles from the cobalt-60 atoms would be emitted asymmetrically and the hypothetical "law of conservation of parity" was invalid. Wu's experiment showed that this is indeed the case: parity is not conserved under the weak nuclear interactions. and are indeed the same particle, which is today known as a kaon

In particle physics, a kaon, also called a K meson and denoted , is any of a group of four mesons distinguished by a quantum number called strangeness. In the quark model they are understood to be bound states of a strange quark (or antiquark ...

, . This result was soon confirmed by her colleagues at Columbia University in different experiments, and as soon as all of these results were published—in two different research papers in the same issue of the same physics journal—the results were also confirmed at many other laboratories and in many different experiments.

The discovery of parity violation was a major contribution to particle physics and the development of the Standard Model

The Standard Model of particle physics is the Scientific theory, theory describing three of the four known fundamental forces (electromagnetism, electromagnetic, weak interaction, weak and strong interactions – excluding gravity) in the unive ...

. The discovery actually set the stage for the development of the model, as the model relied on the idea of symmetry of particles and forces and how particles can sometimes break that symmetry. The wide coverage of her discovery prompted the discoverer of fission Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Otto Stern and Immanuel Estermann, he first measured the magnetic moment of the proton. With his aunt, Lise M ...

to mention that those at Princeton would often say that her experiment was the most impactful since the Michelson–Morley experiment

The Michelson–Morley experiment was an attempt to measure the motion of the Earth relative to the luminiferous aether, a supposed medium permeating space that was thought to be the carrier of light waves. The experiment was performed between ...

that inspired Einstein's theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

. The AAUW

The American Association of University Women (AAUW), officially founded in 1881, is a non-profit organization that advances equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research. The organization has a nationwide network of 170,00 ...

called it the solution to the biggest riddle in science. Beyond showing the distinct characteristic of weak interaction

In nuclear physics and particle physics, the weak interaction, weak force or the weak nuclear force, is one of the four known fundamental interactions, with the others being electromagnetism, the strong interaction, and gravitation. It is th ...

from the other three conventional forces of interaction, this eventually led to the general CP violation

In particle physics, CP violation is a violation of CP-symmetry (or charge conjugation parity symmetry): the combination of C-symmetry (charge conjugation symmetry) and P-symmetry ( parity symmetry). CP-symmetry states that the laws of physics s ...

or the violation of the charge conjugation parity symmetry. This violation meant researchers could distinguish matter from antimatter and create a solution that would explain the existence of the universe as one that is filled with matter. This is because the lack of symmetry gave the possibility of matter–antimatter imbalance which would allow matter to exist today through the Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

.

Lee and Yang were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prize, Nobel Prizes establi ...

in 1957 for their theoretical work, despite a "firm tradition" of the vast majority of the previous and following prizes being awarded to experimentalists, not theorists. Wu's critical contribution providing the experimental confirmation proving the CP violation through her rigorous experiment was omitted by the Nobel committee. Yang and Lee tried to nominate Wu for a future Nobel prize and thanked her in their speeches. She was nominated at least seven times before 1966, when the Nobel committee announced they would conceal their list of nominees to avoid further public controversy. 1988 Nobel laureate Jack Steinberger frequently called it the biggest mistake of the Nobel committee. Wu's role in the discovery was not publicly honored until 1978, when she was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize

The Wolf Prize is an international award granted in Israel, that has been presented most years since 1978 to living scientists and artists for "achievements in the interest of mankind and friendly relations among people ... irrespective of natio ...

.

Wu's friend Pauli, who was notable for being the creator of the Pauli exclusion principle

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli exclusion principle (German: Pauli-Ausschlussprinzip) states that two or more identical particles with half-integer spins (i.e. fermions) cannot simultaneously occupy the same quantum state within a system that o ...

, was certain parity was true and was shocked with the discovery. He, like many other known physicists, lost a large hypothetical bet for wagering against the eventual outcome. He later wrote about his feelings on the discovery to Princeton colleague John M. Blatt: "I don't know whether anyone has written you as yet about the sudden death of parity. Miss Wu has done an experiment with beta-decay of oriented Co nuclei which shows that parity is not conserved in β decay. ... We are all rather shaken by the death of our well-beloved friend, parity." He later became even more confounded when he learned that Wu was denied the Nobel prize, and even believed that he had predicted the event through his dream analysis conducted by Dr. Carl Gustav Jung.

Weak force and conserved vector current

Wu quickly became a full professor in 1958, and later on was named the first Michael I. Pupin Professor of Physics in 1973. Some of her impish students called her the Dragon Lady, after the character of that name in the comic strip ''Terry and the Pirates

''Terry and the Pirates'' is an action-adventure comic strip created by cartoonist Milton Caniff, which originally ran from October 22, 1934, to February 25, 1973. Captain Joseph Patterson, editor for the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndica ...

'' due to Wu's strictness and high standards of excellence. Regardless of this, Wu actually treated her students like her children and often ate lunch with them as well as got to know their entourages. She would do this while working from 8 am to 7 or 8 in the evening, with her pay still very low until it was drastically increased after Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

was installed as the new chairman. Her discoveries proved to be important in physics and her work even crossed over to biology and medicine, where her contributions became extremely influential to certain studies on the molecular changes in red blood cells that caused sickle cell disease or anemia.

In December 1962, Wu experimentally demonstrated a universal form and more accurate version of Fermi's old beta decay model, confirming the conserved vector current (CVC) hypothesis of Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

and Murray Gell-Mann

Murray Gell-Mann (; September 15, 1929 – May 24, 2019) was an American theoretical physicist who played a preeminent role in the development of the theory of elementary particles. Gell-Mann introduced the concept of quarks as the funda ...

on the road to the Standard Model. She would release the results in the succeeding year. In this experiment, she was approached by Gell-Mann after he and Feynman realized they needed an expert on experimental physics to prove their hypothesis. Gell-Mann pleaded to Wu, "How long did Yang and Lee pursue you to follow upon their work?" Their hypothesis was influenced by Wu's demonstration that parity was not conserved, which brought other assumptions that physicists have made about the weak interaction into question. The question was if parity cannot be conserved in weak force interaction, then the conservation of charge conjugation

In physics, charge conjugation is a transformation that switches all particles with their corresponding antiparticles, thus changing the sign of all charges: not only electric charge but also the charges relevant to other forces. The term C- ...

could also be in dispute. Conservation and symmetry were basic laws that held true for electromagnetism, gravity, and the strong interaction, so it had been assumed for decades that they should also hold for the weak interaction until Wu debunked these laws. This was also crucial to the future discovery of the electroweak force.

Wu worked with a number of student assistants including Y.K. Lee, Mo Wei or L.W. Mo, and Lee Rong-Gen from Korea. Using a Van de Graaff accelerator at Columbia with proton, heavy hydrogen, and helium beams, they were able to perform their notable experiment. The beta ray spectra were measured in the magnetometer spectroscopy fifty feet from the accelerator. The beta decay sources B-12 and N-12 were produced in the magnetometer. The laboratories were locked during midnight and Mo had to create a duplicate key for everyone to sneak in and out of the laboratory during the wee hours of the morning. Mo would escort Wu to her Manhattan apartment home. Wu's discovery was presented at the Hilton hotel

Hilton Hotels & Resorts (formerly known as Hilton Hotels) is a global brand of full-service hotels and resorts and the flagship brand of American multinational hospitality company Hilton Worldwide.

The original company was founded by Conrad Hi ...

on January 26, 1963. Wu was pleased with the achievement and mentioned that it gave a complete foundation for Fermi's theory of beta decay as well as provide support for the theory of the two-component neutrino, which her parity experiment first established. Feynman was very happy with the announcement and was so proud of the outcome that he called the CVC theory, together with his diagram

A diagram is a symbolic Depiction, representation of information using Visualization (graphics), visualization techniques. Diagrams have been used since prehistoric times on Cave painting, walls of caves, but became more prevalent during the Age o ...

and work in quantum electrodynamics

In particle physics, quantum electrodynamics (QED) is the Theory of relativity, relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics. In essence, it describes how light and matter interact and is the first theory where full agreement between quant ...

, one of his finest scientific accomplishments.

Later in the 1960s, Wu conducted more experiments on beta decay, specifically on double beta decay

In nuclear physics, double beta decay is a type of radioactive decay in which two neutrons are simultaneously transformed into two protons, or vice versa, inside an atomic nucleus. As in single beta decay, this process allows the atom to move cl ...

. She went inside a 2,000 ft deep salt mine below Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

in Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

to investigate on muonic atoms in which muons take the place of

electrons in normal atoms. The work conducted here would pave the way for its future discovery in the 1980s.

Wu later wrote a textbook with Steven Moszkowski entitled ''Beta Decay'', which was published in 1966. It was the first comprehensive study on beta decay, and the book quickly became the standard reference on the subject; it remains one of the standard references in the 21st century.

Later years and social advocacy

Wu's older brother died in 1958, her father the next year, and her mother in 1962. TheUnited States State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

had imposed severe restrictions on travel to Communist countries by its citizens, so Wu was not permitted to visit mainland China to attend their funerals. She saw her uncle, Wu Zhou-Zhi, and younger brother, Wu Chien-Hao, on a trip to Hong Kong in 1965. After the 1972 Nixon visit to China

From February 21 to 28, 1972, President of the United States Richard Nixon visited Beijing, capital of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in the culmination of his administration's efforts to establish relations with the PRC after years of ...

, relations between the two countries improved, and she visited China again in 1973. Wu nearly visited in 1956, but decided to stay in the US to finish her famous experiment while her husband visited China. By the time she returned, her uncle and brother had perished in the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a Social movement, sociopolitical movement in the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). It was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 and lasted until his de ...

, and the tombs of her parents had been destroyed. She was greeted by Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

, who personally apologized for the destruction of the tombs. After this, she returned to China and Taiwan several times.

During the late 20th century, Wu continued to be seen as the top experimental physicist in the world and many continued to ask for her guidance in proving certain hypotheses. Herwig Schopper

Herwig Franz Schopper (born 28 February 1924) is a German experimental physicist. He was the director general of CERN from 1981 to 1988.

Biography

Schopper was born in Lanškroun, Czechoslovakia, to a family of Austrian descent. He obtained hi ...

, who was the director general of CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN (; ; ), is an intergovernmental organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, it is based in Meyrin, western suburb of Gene ...

, commented that physicists believed "if the experiment was done by Wu, it must be correct." She conducted experiments on Mössbauer spectroscopy

Mössbauer spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique based on the Mössbauer effect. This effect, discovered by Rudolf Mössbauer (sometimes written "Moessbauer", German: "Mößbauer") in 1958, consists of the nearly recoil-free emission and a ...

and its application in the study of sickle cell anemia

Sickle cell disease (SCD), also simply called sickle cell, is a group of inherited haemoglobin-related blood disorders. The most common type is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying ...

. She researched on the molecular changes in the deformation of hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin ...

s that cause this form of anemia. She also did research on magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

in the 1960s. Wu would later work on Bell's theorem

Bell's theorem is a term encompassing a number of closely related results in physics, all of which determine that quantum mechanics is incompatible with local hidden-variable theories, given some basic assumptions about the nature of measuremen ...

, which showed results that confirmed the orthodox interpretation of quantum mechanics.

In later life, Wu became more outspoken. She protested the imprisonment in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

of the in-laws of physicist Kerson Huang in 1959 and of the journalist Lei Chen

Lei Chen (; 8 July 1897 – 7 March 1979) was a Chinese people, Chinese politician and dissident who was the early leading figure in the movement to bring fuller democracy to the government of the Republic of China.

Born in Zhejiang in 1897, Le ...

in 1960. With the help of her teacher Hu Shih, Huang's in-laws were eventually released on bail. Lei's sentence was reduced to ten years by President Chiang Kai-shek. In 1964, she spoke out against gender discrimination at a symposium at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

. "I wonder," she asked her audience, "whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment", which garnered heavy applause from the audience. When men referred to her as Professor Yuan, she immediately corrected them and told them that she was Professor Wu.

In 1975, physics department chairman Serber discovered that Wu had a much lower pay than her male colleagues but that she had never reported on it, so he adjusted her pay to make it equal to that of her male counterparts even if Wu only cared about the research at Columbia. Wu later quipped, In China there are many, many women in physics. There is a misconception in America that women scientists are all dowdy spinsters. This is the fault of men. In Chinese society, a woman is valued for what she is, and men encourage her to accomplishments, yet she remains eternally feminine.Wu's advocacies and conviction maintained a strong priority for the advancement of the sciences. Later in 1975 as the first female president of the

American Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is a not-for-profit membership organization of professionals in physics and related disciplines, comprising nearly fifty divisions, sections, and other units. Its mission is the advancement and diffusion of ...

, Wu met with President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

to formally request him to create an advisory scientific body for the president, which President Ford granted and signed into law the formation of the Office of Science and Technology Policy

The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) is a department of the United States government, part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, Executive Office of the President (EOP), established by United States Congres ...

.

Wu also continued to be an advocate for human rights issues as she protested the crackdown in China that followed the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. In 1978, she was awarded the first Wolf Prize in Physics. One of its criteria considered those who were thought deserving to win a Nobel Prize without receiving one. She retired in 1981 and became a professor emerita

''Emeritus/Emerita'' () is an honorary title granted to someone who retirement, retires from a position of distinction, most commonly an academic faculty position, but is allowed to continue using the previous title, as in "professor emeritus".

...

.

Final years and legacy

Wu would spend most of her time in her later years visiting the

Wu would spend most of her time in her later years visiting the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, and different American states. She became renowned for her steadfast promotion of teaching STEM

Stem or STEM most commonly refers to:

* Plant stem, a structural axis of a vascular plant

* Stem group

* Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

Stem or STEM can also refer to:

Language and writing

* Word stem, part of a word respon ...