Chassternbergia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Edmontonia'' is a genus of panoplosaurin

''Edmontonia'' was bulky, broad and

''Edmontonia'' was bulky, broad and

In 1990,

In 1990,

The skull of ''Edmontonia'', up to half a metre long, is somewhat elongated with a protruding truncated snout. The snout carried a horny upper beak and the front snout bones, the

The skull of ''Edmontonia'', up to half a metre long, is somewhat elongated with a protruding truncated snout. The snout carried a horny upper beak and the front snout bones, the  The head armour tiles, or ''caputegulae'', are smooth. Details differ between the various specimens but all share a large central nasal tile on the snout, bend large "loreal" tiles at the rear snout edges and a large central ''caputegula'' on the skull roof. The tiles behind the upper eye socket rim in ''Edmontonia longiceps'' do not stick out as much as in ''E. rugosidens'', combined with a more narrow, pointed snout in the former. Some ''E. rugosidens'' specimens are known that possess a "cheek plate" above the lower jaw. Contrary to that discovered with ''Panoplosaurus'', it is "free-floating", not fused with the lower jaw bone.

The

The head armour tiles, or ''caputegulae'', are smooth. Details differ between the various specimens but all share a large central nasal tile on the snout, bend large "loreal" tiles at the rear snout edges and a large central ''caputegula'' on the skull roof. The tiles behind the upper eye socket rim in ''Edmontonia longiceps'' do not stick out as much as in ''E. rugosidens'', combined with a more narrow, pointed snout in the former. Some ''E. rugosidens'' specimens are known that possess a "cheek plate" above the lower jaw. Contrary to that discovered with ''Panoplosaurus'', it is "free-floating", not fused with the lower jaw bone.

The

Apart from the head armour, the body was covered with

Apart from the head armour, the body was covered with

In 1915, the

In 1915, the  * ''E. rugosidens''. This species has been given its own genus, ''Chassternbergia'', first coined as a

* ''E. rugosidens''. This species has been given its own genus, ''Chassternbergia'', first coined as a

The large spikes were probably used between males in contests of strength to defend territory or gain mates. The spikes would also have been useful for intimidating predators or rival males, passive protection, or for active self-defense. The large forward pointing shoulder spikes could have been used to run through attacking theropods. Carpenter suggested that the larger spikes of AMNH 5665 indicated this was a male specimen, a case of sexual dimorphism. However, he admitted the possibility of ontogeny, older individuals having longer spikes, as the specimen was relatively large. Traditionally it had been assumed that to protect themselves from predators, nodosaurids like ''Edmontonia'' might have crouched down on the ground to minimize the possibility of attack to their defenseless underbelly, trying to prevent being flipped over by a predator.

The large spikes were probably used between males in contests of strength to defend territory or gain mates. The spikes would also have been useful for intimidating predators or rival males, passive protection, or for active self-defense. The large forward pointing shoulder spikes could have been used to run through attacking theropods. Carpenter suggested that the larger spikes of AMNH 5665 indicated this was a male specimen, a case of sexual dimorphism. However, he admitted the possibility of ontogeny, older individuals having longer spikes, as the specimen was relatively large. Traditionally it had been assumed that to protect themselves from predators, nodosaurids like ''Edmontonia'' might have crouched down on the ground to minimize the possibility of attack to their defenseless underbelly, trying to prevent being flipped over by a predator.

nodosaurid

Nodosauridae is a family of ankylosaurian dinosaurs known from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous periods in what is now Asia, Europe, North America, and possibly South America. While traditionally regarded as a monophyletic clade as the s ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

from the Late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

Period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Period (punctuation)

* Era, a length or span of time

*Menstruation, commonly referred to as a "period"

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (o ...

. It is part of the Nodosauridae

Nodosauridae is a family of ankylosaurian dinosaurs known from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous periods in what is now Asia, Europe, North America, and possibly South America. While traditionally regarded as a monophyletic clade as the ...

, a family within Ankylosauria

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the clade Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs ...

. It is named after the Edmonton Formation (now the Horseshoe Canyon Formation

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of th ...

in Canada), the unit of rock where it was found.

Description

Size and general build

tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

-like. Its length has been estimated at 6.6 m (22 ft). In 2010, Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology. He is best known for his work and research on theropoda, theropod dinosaurs and his detailed illustrations, both l ...

considered both main ''Edmontonia'' species, ''E. longiceps'' and ''E. rugosidens'', to be equally long at six metres and weigh three tonnes.Paul, G.S., 2010, ''The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs'', Princeton University Press p. 238

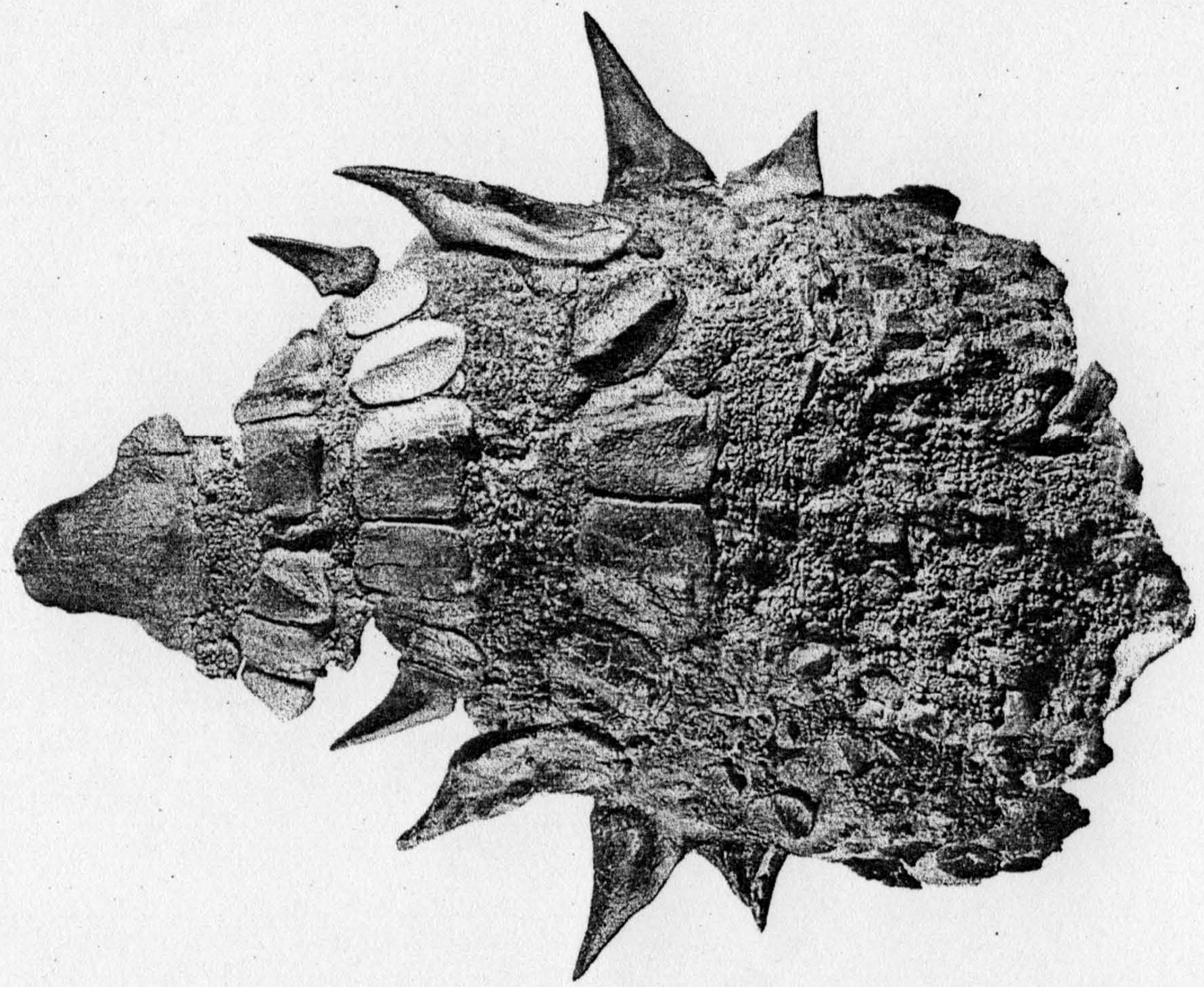

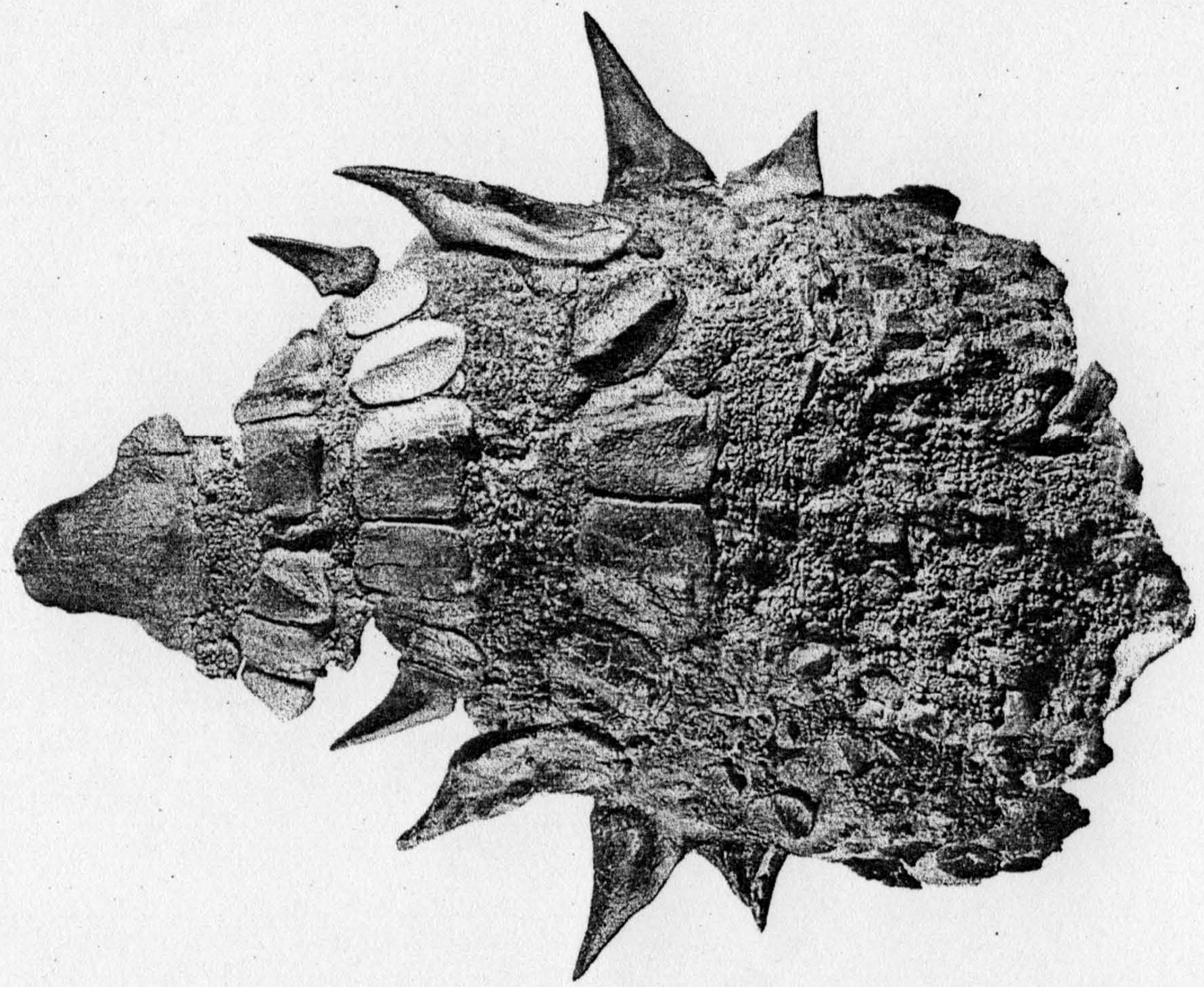

''Edmontonia'' had small, oval ridged bony plates on its back and head and many sharp spikes along its sides. The four largest spikes jutted out from the shoulders on each side, the second of which was split into subspines in ''E. rugosidens'' specimens. Its skull had a pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in late summer into mid-autumn. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the Family (biology), family Rosaceae, bearing the Pome, po ...

-like shape when viewed from above. Its neck and shoulders were protected by three halfrings made of large keeled plates.

Distinguishing traits

In 1990,

In 1990, Kenneth Carpenter

Kenneth Carpenter (born 21 September 1949) is an American paleontologist. He is the former director of the USU Eastern Prehistoric Museum and author or co-author of books on dinosaurs and Mesozoic life. His main research interests are armore ...

established some diagnostic traits for the genus as a whole, mainly comparing it with its close relative ''Panoplosaurus

''Panoplosaurus'' is a genus of armoured dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. Few specimens of the genus are known, all from the middle Campanian of the Dinosaur Park Formation, roughly 76 to 75 million years ago. It was first d ...

''. In top view, the snout has more parallel sides. The skull armour has a smooth surface. In the palate, the vomer

The vomer (; ) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms ...

is keeled. The neural arch

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

es and neural spine

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

s are shorter than those of ''Panoplosaurus''. The sacrum proper consists of three sacral vertebrae. In the shoulder girdle, the scapula and coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

are not fused.

Carpenter also indicated in which way the main species differed from each other. The type species, ''Edmontonia longiceps'', is distinguished from ''E. rugosidens'' in lacking sideways projecting osteoderms behind the eye sockets; having tooth rows that are less divergent; possessing a more narrow palate; having a sacrum that is wider than long and more robust; and in having shorter spikes at the sides. Also, an ossified cheek plate, known from ''E. rugosidens'' specimens, has not been found with ''Edmontonia longiceps''.

Skeleton

The skull of ''Edmontonia'', up to half a metre long, is somewhat elongated with a protruding truncated snout. The snout carried a horny upper beak and the front snout bones, the

The skull of ''Edmontonia'', up to half a metre long, is somewhat elongated with a protruding truncated snout. The snout carried a horny upper beak and the front snout bones, the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

e, were toothless. The cutting edge of the upper beak continued into the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

ry tooth rows, each containing fourteen to seventeen small teeth. In each dentary of the lower jaws, eighteen to twenty-one teeth were present. In the sides of the snout large depressions were present, "nasal vestibules", that each possessed two smaller openings. The top of these was a horizontal oval and represented the bony external nostril, the entrance to the nasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nas ...

, the normal air passage. The more rounded second opening below and obliquely in front, was the entrance to a "paranasal" tract, running along the outer side of the nasal cavity, in a somewhat lower position. A study by Matthew Vickaryous in 2006 proved for the first time the presence of multiple openings in a nodosaurid; such structures had already been well established in ankylosaurids. The air tracts are however, much simpler than in the typical ankylosaurid condition, and are not convoluted while lacking bony turbinate bones. The nasal cavity is separated into two halves along the midline by a bone wall. This septum

In biology, a septum (Latin language, Latin for ''something that encloses''; septa) is a wall, dividing a Body cavity, cavity or structure into smaller ones. A cavity or structure divided in this way may be referred to as septate.

Examples

Hum ...

is continued to below by the vomer

The vomer (; ) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms ...

s, which are keeled, the keel featuring a pendulum-shaped appendage. Another similarity with Ankylosauridae is the presence of a secondary bone palate, a possible case of parallel evolution

Parallel evolution is the similar development of a trait in distinct species that are not closely related, but share a similar original trait in response to similar evolutionary pressure.Zhang, J. and Kumar, S. 1997Detection of convergent and pa ...

. This has been shown too for ''Panoplosaurus''.

The head armour tiles, or ''caputegulae'', are smooth. Details differ between the various specimens but all share a large central nasal tile on the snout, bend large "loreal" tiles at the rear snout edges and a large central ''caputegula'' on the skull roof. The tiles behind the upper eye socket rim in ''Edmontonia longiceps'' do not stick out as much as in ''E. rugosidens'', combined with a more narrow, pointed snout in the former. Some ''E. rugosidens'' specimens are known that possess a "cheek plate" above the lower jaw. Contrary to that discovered with ''Panoplosaurus'', it is "free-floating", not fused with the lower jaw bone.

The

The head armour tiles, or ''caputegulae'', are smooth. Details differ between the various specimens but all share a large central nasal tile on the snout, bend large "loreal" tiles at the rear snout edges and a large central ''caputegula'' on the skull roof. The tiles behind the upper eye socket rim in ''Edmontonia longiceps'' do not stick out as much as in ''E. rugosidens'', combined with a more narrow, pointed snout in the former. Some ''E. rugosidens'' specimens are known that possess a "cheek plate" above the lower jaw. Contrary to that discovered with ''Panoplosaurus'', it is "free-floating", not fused with the lower jaw bone.

The vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

contains about eight neck vertebrae, about twelve "free" back vertebrae, a "sacral rod" of four fused rear dorsal vertebrae, three sacral vertebrae, two caudosacrals and at least twenty, but probably about forty, tail vertebrae. In the neck the first two vertebrae, the atlas and axis, are fused. In the shoulder girdle, the coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

has a rectangular profile, in contrast to the more rounded shape with ''Panoplosaurus''. Two sternal plates are present, connected to sternal ribs. The forelimb is robust but relatively long. In ''Edmontonia longiceps'' and ''E. rugosidens'' the deltopectoral crest of the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

is gradually rounded. The metacarpus

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular skeleton, appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones (wrist, wris ...

is robust compared to that of ''Panoplosaurus''. The hand very likely was tetradactyl, having four fingers. The exact number of phalanges is unknown but the formula was by W.P. Coombs suggested to be 2-3-3-4-?.

Osteoderms

Apart from the head armour, the body was covered with

Apart from the head armour, the body was covered with osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amph ...

s, skin ossifications. The configuration of the armour of ''Edmontonia'' is relatively well known, much of it having been discovered in articulation. The neck and shoulder region was protected by three cervical halfrings, each consisting of fused rounded rectangular, asymmetrically keeled, bone plates. These halfrings did not have a continuous underlying bone band. The first and second halfrings each had three pairs of segments. Below each lower end of the second halfring a side spike was present, a separate triangular osteoderm pointing obliquely forward. In the third halfring over the shoulders, the two pairs of central segments are bordered on each side by a very large forward-pointing spike that is bifurcated, featuring a secondary point above the main one. A third large spike behind it points more sideways; a smaller fourth one, often connected to the third at the base, is directed obliquely to behind. The row of side spikes is continued to the rear but there the osteoderms are much lower, curving strongly to behind, with the point overhanging the rear edge. Gilmore had trouble believing that the shoulder spikes really pointed to the front as this would have greatly hampered the animal while moving through vegetation. He suggested that the points had shifted during the burial of the carcass. However, Carpenter and G.S. Paul, trying to reposition the spikes, found that it was impossible to rotate them without losing conformity with the remainder of the armour. The side spikes have solid, not hollow, bases. The spikes differ in size between ''E. rugosidens'' individuals; those of the ''E. longiceps'' holotype are relatively small.

Behind the third halfring the back and hip are covered by numerous transverse rows of much smaller oval keeled osteoderms. These are not ordered in longitudinal rows. The front rows have plates oriented along the length of the body, but to the rear the long axis of these osteoderms gradually rotates sideways, their keels ultimately running transversely. Rosettes are lacking. The configuration of the tail armour is unknown. The larger plates of all body parts were connected by small ossicles. Such small round scutes also covered the throat.

Discovery and species

In 1915, the

In 1915, the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

obtained the nearly complete, articulated front half of an armoured dinosaur, found the same year by Barnum Brown

Barnum Brown (February 12, 1873 – February 5, 1963), commonly referred to as Mr. Bones, was an American paleontologist. He discovered the first documented remains of ''Tyrannosaurus'' during a career that made him one of the most famous fossil ...

in Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, Canada. In 1922, William Diller Matthew

William Diller Matthew FRS (February 19, 1871 – September 24, 1930) was a vertebrate paleontologist who worked primarily on mammal fossils, although he also published a few early papers on mineralogy, petrological geology, one on botany, one on ...

referred this specimen, AMNH 5381, to ''Palaeoscincus

''Palaeoscincus'' (meaning "ancient lizard" from and ) is a dubious genus of ankylosaurian dinosaur based on teeth from the mid-late Campanian-age Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana. Like several other dinosaur genera named ...

'' in a popular-science article, not indicating any particular species. It had been intended to name a new ''Palaeoscincus'' species in cooperation with Brown but their article was never published. Matthew also referred specimen AMNH 5665, the front of a skeleton found by Levi Sternberg in 1917. In 1930 Charles Whitney Gilmore

Charles Whitney Gilmore (March 11, 1874 – September 27, 1945) was an American paleontologist who gained renown in the early 20th century for his work on vertebrate fossils during his career at the United States National Museum (now the N ...

referred both specimens to ''Palaeoscincus rugosidens''. This species was based on type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

USNM 11868, a skeleton found by George Fryer Sternberg

George Fryer Sternberg (1883 – 23 October 1969) was an American paleontologist best known for his discovery in Gove County, Kansas of the "fish-within-a-fish" of ''Xiphactinus audax'' with a recently eaten ''Gillicus arcuatus'' within its stom ...

in June 1928. The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

is derived from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''rugosus'', "rough", and ''dens'', "tooth". In 1940, Loris Shano Russell

Loris is the common name for the strepsirrhine mammals of the subfamily Lorinae (sometimes spelled Lorisinae) in the family Lorisidae. ''Loris'' is one genus in this subfamily and includes the slender lorises, ''Nycticebus'' is the genus contain ...

referred all three specimens to ''Edmontonia'', as an ''Edmontonia rugosidens''.

Meanwhile, the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of ''Edmontonia'', ''Edmontonia longiceps'', had been named by Charles Mortram Sternberg

Charles Mortram Sternberg (18 September 1885 – 8 September 1981) was an American-Canadian fossil collector and paleontologist, son of Charles Hazelius Sternberg.

Late in his career, he collected and described '' Pachyrhinosaurus'', ''Brachylop ...

in 1928. The generic name ''Edmontonia'' refers to Edmonton

Edmonton is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Alberta. It is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Central Alberta ...

or the Edmonton Formation. The specific name ''longiceps'' means "long-headed" in Latin. Its holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

is specimen NMC 8531, consisting of a skull, right lower jaw and much of the postcranial skeleton, including the armour. It was discovered near Morrin in 1924 by George Paterson, the teamster of the expedition led by C.M. Sternberg.

''Edmontonia'' species include:

* ''E. longiceps'', the type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* ...

, known from a complete skull, is known from the middle Horseshoe Canyon Formation

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of th ...

(Unit 2) which used to be dated to 71.5-71 million years ago. This unit, which straddles the Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campa ...

-Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian ( ) is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age (uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage) of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or Upper Cretaceous series (s ...

boundary, has since been recalibrated to an age of about 72 million years. Isolated bones and shed teeth from ''E. longiceps'' are also known from the upper Judith River Formation in Montana.

* ''E. rugosidens''. This species has been given its own genus, ''Chassternbergia'', first coined as a

* ''E. rugosidens''. This species has been given its own genus, ''Chassternbergia'', first coined as a subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

by Dr. Robert Thomas Bakker in 1988, as ''Edmontonia (Chassternbergia) rugosidens'' and is based on differences in skull proportion from ''E. longiceps'' and its earlier time period.Bakker, R.T. (1988). Review of the Late Cretaceous nodosauroid Dinosauria: ''Denversaurus schlessmani'', a new armor

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

-plated dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of South Dakota, the last survivor of the nodosaurians, with comments on Stegosaur-Nodosaur relationships. ''Hunteria'' 1(3):1-23.(1988).Ford, T.L. (2000). A review of ankylosaur osteoderms from New Mexico and a preliminary review of ankylosaur armor. In: Lucas, S.G., and Heckert, A.B. (eds.). ''Dinosaurs of New Mexico.'' New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 17:157-176. It was given its full generic name in 1991 by George Olshevsky

George may refer to:

Names

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

People

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Papagheorghe, also known as Jorge / GEØRGE

* George, stage name of Giorg ...

. The name ''Chassternbergia'' honours Charles, "Chas", M. Sternberg. This subgenus or genus name is rarely applied. ''E. rugosidens'' is found in the Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campa ...

lower Dinosaur Park Formation

The Dinosaur Park Formation is the uppermost member of the Belly River Group (also known as the Judith River Group), a major geologic unit in southern Alberta. It was deposited during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, between about 7 ...

, dating from about 76.5-75 million years ago. Many later finds have been referred to ''E. rugosidens'', among them CMN 8879, the top of a skull found in 1937 by Harold D'acre Robinson Lowe; ROM 433, a forked spine found by Jack Horner Jack Horner may refer to:

*"Little Jack Horner", a nursery rhyme

People

* Jack Horner (activist) (born 1922), Australian author and activist in the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship

* Jack Horner (baseball) (1863–1910), American professional ba ...

in 1986 among ''Oohkotokia

''Oohkotokia'' ( ) is a genus of ankylosaurid dinosaur within the subfamily Ankylosaurinae. It is known from the upper levels of the Two Medicine Formation (late Campanian stage, about 74 Ma ago) of Montana, United States. The discovery of ''O ...

'' material; ROM 5340, paired medial plates; ROM 1215, a skeleton; RTMP 91.36.507, a skull; RTMP 98.74.1, a possible ''Edmontonia'' skull; RTMP 98.71.1, a skeleton; RTMP 98.98.01, a skull and right lower jaw; and RTMP 2001.12.158, a skull.

''Edmontonia schlessmani'' was a renaming in 1992 of '' Denversaurus schlessmani'' ("Schlessman's Denver

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

") by Adrian Hunt and Spencer Lucas

Spencer George Lucas is an American paleontologist and stratigrapher, and curator of paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. His main areas of study are late Paleozoic, Mesozoic and early Cenozoic vertebrate fossils ...

. This taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

was erected by Bakker in 1988 for a skull from the Late Maastrichtian Upper Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cret ...

lower Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The Formation (stratigraphy), formation s ...

of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, specimen DMNH 468 which was first described as ''Edmontonia'' sp. by Carpenter and Breithaupt (1986). This holotype, type specimen of ''Denversaurus'' is in the collections of the Denver Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature and Science), Denver, Colorado for which the genus was named. The specific name honours Lee E. Schlessman, whose Schlessman Family Foundation sponsored the museum. Bakker described the skull as being much wider at the rear than ''Edmontonia'' specimens. However, later workers explained this by its being crushed,Carpenter, K. 1990. "Ankylosaur systematics: example using ''Panoplosaurus'' and ''Edmontonia'' (Ankylosauria: Nodosauridae)", In: Carpenter, K. & Currie, P.J. (eds) ''Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives'', Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 281-298 and considered the taxon a junior synonym of ''Edmontonia longiceps''. The Black Hills Institute has referred a skeleton (BHI 127327) from the Lance Formation to ''Denversaurus'', referred to as ''E. schlessmani'' by Carpenter et al. (2013). Recent phylogenetic analyses included ''Denversaurus'' as a valid genus closely related to ''Edmontonia''.

''Edmontonia australis'' was named by Tracy Lee Ford in 2000 on the basis of cervical scutes, the holotype NMMNH P-25063, a pair of medial keeled neck osteoderms from the Maastrichtian Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and the paratype NMMNH P-27450, a right middle neck plate. Although later considered to a nomen dubium, dubious name, it is now considered a junior synonym of ''Glyptodontopelta mimus.''

The naming history was further complicated in 1971, when Walter Preston Coombs Jr renamed both ''Edmontonia'' species, into ''Panoplosaurus

''Panoplosaurus'' is a genus of armoured dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. Few specimens of the genus are known, all from the middle Campanian of the Dinosaur Park Formation, roughly 76 to 75 million years ago. It was first d ...

longiceps'' and ''Panoplosaurus rugosidens'' respectively. The latter species, which due to its much more complete material has determined the image of ''Edmontonia'', until 1940 thus appeared under the name of ''Palaeoscincus'', and during the 1970s and 1980s was shown as "Panoplosaurus" until newer research revived the name ''Edmontonia''.

In 2010, G.S. Paul suggested that ''E. rugosidens'' was the direct ancestor of ''Edmontonia longiceps'' and the latter was again the direct ancestor of ''E. schlessmani''.

Phylogeny

C.M. Sternberg originally did not provide a classification of ''Edmontonia''. In 1930, L.S. Russell placed the genus in theNodosauridae

Nodosauridae is a family of ankylosaurian dinosaurs known from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous periods in what is now Asia, Europe, North America, and possibly South America. While traditionally regarded as a monophyletic clade as the ...

, which has been confirmed by subsequent analyses. ''Edmontonia'' was generally shown to be a derived nodosaurid, closely related to ''Panoplosaurus''. Russell in 1940 named a separate Edmontoniinae. In 1988 Bakker proposed that the Edmontoniinae with the Panoplosaurinae should be joined into Nodosaurinae, Edmontoniidae, the presumed sister group of the Nodosauridae within Nodosauridae, Nodosauroidea which he assumed not be ankylosaurians but the last surviving stegosaurians. Exact cladistic analysis has not confirmed these hypotheses however, and the concepts of Edmontoniinae and Edmontoniidae are not in modern use.

''Edmontonia'' has been found as a close relative of ''Panoplosaurus'' in phylogenetic analysis, including in the 2018 in paleontology, 2018 phylogenetic analysis of Rivera-Sylva and colleagues shown below; limited to the relationships within Panoplosaurini.

Paleobiology

Function of the armour

The large spikes were probably used between males in contests of strength to defend territory or gain mates. The spikes would also have been useful for intimidating predators or rival males, passive protection, or for active self-defense. The large forward pointing shoulder spikes could have been used to run through attacking theropods. Carpenter suggested that the larger spikes of AMNH 5665 indicated this was a male specimen, a case of sexual dimorphism. However, he admitted the possibility of ontogeny, older individuals having longer spikes, as the specimen was relatively large. Traditionally it had been assumed that to protect themselves from predators, nodosaurids like ''Edmontonia'' might have crouched down on the ground to minimize the possibility of attack to their defenseless underbelly, trying to prevent being flipped over by a predator.

The large spikes were probably used between males in contests of strength to defend territory or gain mates. The spikes would also have been useful for intimidating predators or rival males, passive protection, or for active self-defense. The large forward pointing shoulder spikes could have been used to run through attacking theropods. Carpenter suggested that the larger spikes of AMNH 5665 indicated this was a male specimen, a case of sexual dimorphism. However, he admitted the possibility of ontogeny, older individuals having longer spikes, as the specimen was relatively large. Traditionally it had been assumed that to protect themselves from predators, nodosaurids like ''Edmontonia'' might have crouched down on the ground to minimize the possibility of attack to their defenseless underbelly, trying to prevent being flipped over by a predator.

Paleoecology

Rings in the petrified wood of trees contemporary with ''Edmontonia'' show evidence of strong seasonal changes in precipitation and temperature; this may hold an explanation for why so many specimens have been found with their armor plating and spikes in the same position they were in life. The ''Edmontonia'' could have died due to drought, dried up, and then rapidly became covered in sediment when the rainy season began."Edmontonia." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. ''The Age of Dinosaurs''. Publications International, LTD. p. 141. . ''Edmontonia rugosidens'' existed in the upper section of theDinosaur Park Formation

The Dinosaur Park Formation is the uppermost member of the Belly River Group (also known as the Judith River Group), a major geologic unit in southern Alberta. It was deposited during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, between about 7 ...

, about 76.5–75 million years ago. It lived alongside numerous other giant herbivores, such as the hadrosaurids ''Gryposaurus'', ''Corythosaurus'' and ''Parasaurolophus'', the ceratopsids ''Centrosaurus'' and ''Chasmosaurus'', and ankylosaurids ''Scolosaurus'' and ''Dyoplosaurus'' Studies of the jaw anatomy and mechanics of these dinosaurs suggests they probably all occupied slightly different ecological niches in order to avoid direct competition for food in such a crowded eco-space.Mallon, J. C., Evans, D. C., Ryan, M. J., & Anderson, J. S. (2012). Megaherbivorous dinosaur turnover in the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. The only large predators known from the same levels of the formation as ''Edmontonia'' are the tyrannosaurids ''Gorgosaurus libratus'' and an unnamed species of ''Daspletosaurus''.

''Edmontonia longiceps'' is known from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of th ...

, from the middle unit, which was dated to 71.5-71 million years ago in 2009. The fauna of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation is well-known, as vertebrate fossils, including those of dinosaurs, are quite common. Sharks, Batoidea, rays, sturgeons, bowfins, gars and the gar-like ''Aspidorhynchus'' made up the fish fauna. The saltwater plesiosaur ''Leurospondylus'' has been found in marine sediments in the Horseshoe Canyon, while freshwater environments were populated by turtles, ''Champsosaurus'', and crocodilians like ''Leidyosuchus'' and ''Stangerochampsa''. Dinosaurs dominate the fauna, especially hadrosaurs, which make up half of all dinosaurs known, including the genera ''Edmontosaurus'', ''Saurolophus'' and ''Hypacrosaurus''. Ceratopsians and ornithomimids were also very common, together making up another third of the known fauna. Along with much rarer ankylosaurians and pachycephalosaurs, all of these animals would have been prey for a diverse array of carnivorous theropods, including troodontids, dromaeosaurids, and caenagnathids. Adult ''Albertosaurus'' was the apex predator in this environment, with intermediate niches possibly filled by juvenile albertosaurs.Eberth, D.A., 1997, "Edmonton group". In: Currie, P.J., Padian, K. (Eds.), ''Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs''. Academic Press, New York, pp. 199–204

See also

* Timeline of ankylosaur researchReferences

External links

{{Taxonbar, from=Q245262 Nodosauridae Dinosaur genera Campanian dinosaurs Maastrichtian dinosaurs Dinosaur Park Formation Horseshoe Canyon Formation Fossil taxa described in 1928 Taxa named by Charles Mortram Sternberg Dinosaurs of Canada