Charles Sydney Goldman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Major Charles Sydney Goldman (28 April 1868 – 7 April 1958) was a British businessman, author, and journalist who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1910 until 1918.

Goldman and his elder brother Alfred returned to South Africa around 1882. Alfred settled at

Goldman and his elder brother Alfred returned to South Africa around 1882. Alfred settled at

* (as translator) ''Cavalry in Future Wars'' (1906), from the German of ''Unsere Kavallerie im nächsten Kriege: Betrachtungen über ihre Verwendung, Organisation und Ausbildung'' (1899) by

One of Goldman's legacies is

One of Goldman's legacies is

Background

In early life, he used the family name in the spelling Goldmann. Born inCape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, he was of German Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

ancestry. His father Bernard Nahum Goldmann had left eastern Germany after the German revolutions of 1848–1849

The German revolutions of 1848–1849 (), the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated p ...

, because of his political involvements. It was reported in 1939 that his family name was originally Monck.

Bernard Goldmann ran a shop at Burgersdorp

Burgersdorp is a medium-sized town in Walter Sisulu in the Joe Gqabi District Municipality of the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

In 1869 a Theological Seminary was established here by the '' Gereformeerde Kerk'', but in 1905 it was mov ...

for the Mosenthal brothers, and prospered; he was appointed Justice of the Peace for the Albert district of Cape Colony in 1869. He was a director of the Albert Bank, with his brother Louis Goldmann, who had arrived in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

in 1845 with his family from Breslau, had gone into business with the Mosenthals and moved to Burgersdorp. The surgeon and medical researcher Edwin Goldmann was Sydney's elder brother.

In 1876 Bernard Goldmann and his family migrated to Europe, by a sea voyage on SS ''Nyanza'' to Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

. After a period in London, they moved on to Breslau. As tutor in German, and to help with college preparation, the children had an uncle, Dr. Monck. The boys also attended the gymnasium school, where Adolf Anderssen

Karl Ernst Adolf Anderssen (6 July 1818 – 13 March 1879)"Anderssen, Adolf" in ''Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 385. was a German chess master. ...

taught. From there, Sydney and his brother Alfred moved back to South Africa; while Edwin and Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language">Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'st ...

, the other brothers, with their sister Alice, remained in Germany.

In business

Goldman and his elder brother Alfred returned to South Africa around 1882. Alfred settled at

Goldman and his elder brother Alfred returned to South Africa around 1882. Alfred settled at Graaff-Reinet

Graaff-Reinet (; Xhosa: eRhafu) is a town in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. It is the oldest town in the province and the fourth oldest town in South Africa, after Cape Town, Stellenbosch, Simon's Town, Paarl and Swellendam. The to ...

as a dealer. Sydney Goldman went into agriculture. He was in business at Reddersburg

Reddersburg is a small sheep and cattle farming town in the Free State province of South Africa on the N6 National Route 60 kilometres south of Bloemfontein.

History

The town was established around the Reformed Church Reddersburg, which was est ...

, in the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

, around 1887.

Gold mines and their finance earned Goldman a fortune. He moved to the goldfields after the Witwatersrand Gold Rush

The Witwatersrand Gold Rush was a gold rush that began in 1886 and led to the establishment of Johannesburg, South Africa. It was a part of the Mineral Revolution.

Origins

In the modern-day province of Mpumalanga, gold miners in the alluvial ...

, and was taken on by a mining company. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

in 1891, as Sydney Goldmann. From age 26, or 1895, he was a partner in S. Neumann & Co., Sigismund Neumann

Sir Sigismund Neumann (Anglicized name Sigmund) (1857 1916) was a mining magnate (Randlord) and financier on the Witwatersrand.

Early life and family

Neumann was born in Fürth, Kingdom of Bavaria, on 25 May 1857 to Jewish parents, Gustav and Ba ...

's holding company, at least to 1905; later (by 1913) Neumann was the sole partner. As the other partners moved to London, Goldman was for a time the only partner resident in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

.

Goldman purchased an extensive estate known as Schoongezicht (later known as Lanzerac) in the Middelburg Middelburg may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Europe

* Middelburg, Zeeland, the capital city of the province of Zeeland, southwestern Netherlands

** Roman Catholic Diocese of Middelburg, a former Catholic diocese with its see in the Zeeland ...

district. By 1900 it was owned by John X. Merriman. Bernard Goldmann having died (by 1894), the family moved by stages to London, with Edwin remaining in Freiburg, Germany

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

; and Sydney left Johannesburg. In 1899 in England he married a granddaughter of Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

.

Boer War

During theSecond Anglo-Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

, Goldman was a war correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war, war zone.

War correspondence stands as one of journalism's most important and impactful forms. War correspondents operate in the most conflict-ridden parts of the wor ...

for ''The Standard

The Standard may refer to:

Entertainment

* The Standard (band), an indie rock band from Portland, Oregon

* ''The Standard'' (novel), a 1934 novel by the Austrian writer Alexander Lernet-Holenia

* ''The Standard'' (Tommy Flanagan album), 1980

* ...

'' and was a major in the British forces. Initially attached to Sir Redvers Buller

General Sir Redvers Henry Buller, (7 December 1839 – 2 June 1908) was a British Army officer and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. He served as Commander-in-Chief ...

's relief force, he travelled with them as far as Ladysmith after which he transferred to the cavalry advancing north in order to report on their endeavours. At this period, Goldman worked as a cameraman for the Warwick Trading Company

The Warwick Trading Company was a British film production and distribution company, which operated between 1898 and 1915.

History

The Warwick Trading Company had its origins in the London office of Maguire and Baucus, a firm run by two American ...

, taking over when Joseph Rosenthal left in the middle of 1900. He is recorded as filming a ceremony on 25 October 1900 in Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

, in which Lord Roberts marked the annexation of the Transvaal. After that Goldman returned to Johannesburg, which had been captured by British forces.

Imperialism and politics

In the 1890s Goldman was involved in theEighty Club

The Eighty Club was a political London gentlemen's club named after the year it was founded, 1880 (much like the later 1900 Club and 1920 Club). It was strictly aligned to the Liberal Party, with members having to pledge support to join. Somew ...

. His brother Richard dined there while Lord Rosebery

Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, 1st Earl of Midlothian (7 May 1847 – 21 May 1929) was a British Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from March 1894 to June 1895. Between the death of h ...

, the Liberal Imperialist The Liberal Imperialists were a faction within the British Liberal Party in the late 1890s and early 1900s, united by views regarding the policy toward the British Empire. They supported the Second Boer War which a majority of Liberals opposed, and ...

, was Prime Minister (i.e. 1894–5). Clinton Edward Dawkins

Sir Clinton Edward Dawkins, (2 November 1859 – 2 December 1905) was a British businessman and civil servant.

Life

Dawkins was born in London, the third son of Clinton George Dawkins, one time Consul-General in Venice, descended from the Daw ...

described Goldman to Leo Maxse in 1904 as:

...full of S. African shares, also of public spirit and of imperial devotion... hodesires to excel as a writer or pamphleteer. Nature—or his education—have deprived him of the least glimmering of literary skill.Goldman joined the

Compatriots Club

The Compatriots Club was an unofficial grouping of British Conservatives between 1904 and 1914. According to E. H. H. Green, the club "was made up of a membership of Conservative MPs, academics, journalists, and writers, functioned as a ...

formed that year. To gain influence, he purchased a struggling weekly journal, '' The Outlook'', at the end of 1904. It had been founded by George Wyndham

George Wyndham, PC (29 August 1863 – 8 June 1913) was a British Conservative politician, statesman, man of letters, and one of The Souls.

Background and education

Wyndham was the elder son of the Honourable Percy Wyndham, third son of G ...

, and was then edited by Percy Hurd

Sir Percy Angier Hurd (18 May 1864 – 5 June 1950) was a British journalist and Conservative Party politician who served as a Member of Parliament for nearly thirty years. He was the first of four generations of Hurds to serve as Conservative ...

. In order to develop it as an organ of the tariff reformers, Goldman hired the journalist J. L. Garvin

James Louis Garvin (12 April 1868 – 23 January 1947) was a British journalist, editor, and author. In 1908, Garvin agreed to take over the editorship of the Sunday newspaper ''The Observer'', revolutionising Sunday journalism and restoring ...

as its editor. Garvin quickly transformed the journal into a publication of note, but the paper failed to turn a profit. After a series of disagreements between the two men over business matters, Goldman sold the paper to Lord Iveagh

Earl of Iveagh (pronounced —especially in Dublin—or ) is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, created in 1919 for the businessman and philanthropist Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, Edward Guinness, 1st Viscount Iveagh. He was ...

in October 1906. On the tone of Edwardian period imperialist writers, contrasted with Leonard Woolf

Leonard Sidney Woolf (; – ) was a British List of political theorists, political theorist, author, publisher, and civil servant. He was married to author Virginia Woolf. As a member of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party and the Fabian Socie ...

, Simon Glassock writes:

Garvin, Goldman and St Loe Strachey demonstrate how writers at the turn of the twentieth century might have allied economics, politics and history with appeals for the reader to take modest but deserved pride in the imperial achievements of the British.Goldman joined the

Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a private members' club in the St James's area of London, England. It was the original home of the Conservative Party before the creation of Conservative Central Office. Membership of the club is by nomination and elect ...

. He was a member of the Unionist Social Reform Committee

The Unionist Social Reform Committee was a group within the British Conservative Party dedicated to help formulating a Conservative policy of social reform between 1911 and 1914. According to E. H. H. Green, the Committee "saw the earliest, detai ...

, while his wife Agnes was on the Council of the Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Association

The Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Association (CUWFA) was a British women's suffrage organisation open to members of the Conservative and Unionist Party. Formed in 1908 by members of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, ...

. He resided at Walpole House which he sold in 1925. He involved himself in politics directly by entering Parliament, winning the Penryn and Falmouth

Penryn and Falmouth was the name of a constituency in Cornwall, England, UK, represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1832 until 1950. From 1832 to 1918 it was a parliamentary borough, initially returning ...

seat in the January 1910 general election

The January 1910 UK general election was held from 15 January to 10 February 1910. Called amid a constitutional crisis after the Conservative-dominated House of Lords rejected the People's Budget, the Liberal government, seeking a mandate, los ...

as a Unionist.

In 1913 Goldman was a captain in the Royal Garrison Artillery

The Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) was formed in 1899 as a distinct arm of the British Army's Royal Artillery, Royal Regiment of Artillery serving alongside the other two arms of the Regiment, the Royal Field Artillery (RFA) and the Royal Horse ...

; and during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, served as a major in it, in Cornwall. As a backbencher he was noted, like Arnold Ward

Arnold Sandwith Ward (1876 – 1950) was an English journalist and Conservative Party politician. He served as the MP for the constituency of Watford between 1910 and 1918.

Biography

Ward was the son of Humphry "Thomas" Ward, a fellow and t ...

, for his "jingoistic

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inter ...

" views. He remained an MP until the borough was abolished in 1918 (the name was transferred to a new county division).

Later life

In 1919 Goldman purchased the Nicola Ranch and most of the Nicola townsite in theNicola Country

The Nicola Country, also known as the Nicola Valley and often referred to simply as The Nicola, and originally Nicolas' Country or Nicholas' Country, adapted to Nicola's Country and simplified since, is a region in the British Columbia Interior, S ...

, British Columbia, which grew to some . He owned all the way up to what is now the Monck Provincial Park

Monck Provincial Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada, located at Nicola Lake near the town of Merritt. The park's campground is one of those which accepts reservations. Activities including fishing, camping and hiking. Natur ...

, named after his son Commander Victor Robert Penryn Monck of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

In England Goldman lived at Trefusis House, Falmouth until about 1929, after which he moved to the Jacobean mansion at Yaverland Manor

Yaverland Manor is a medieval manor house in Yaverland, near Sandown, on the Isle of Wight. It was reconstructed in c. 1620 with alterations c. 1709. It became a Grade I listed building in 1949.

History

The house was erected with many stellas i ...

.

Works

Goldman wrote an eyewitness account of the Boer War, and edited and translated other works. * ''The financial, statistical, and general history of the gold & other companies of Witwatersrand, South Africa'' (1892) * ''South African Mines'': Volume I (1895): Rand mining companies and two succeeding volumes, II on Miscellaneous Companies, and III on maps (1896) * ''With General French and the Cavalry in South Africa'' (1902). The illustrations to the book included a number of photographs taken by Charles Howard Foulkes of theRoyal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

, who used a Newman & Guardia

Newman & Guardia was a British company that manufactured cameras and other fine instruments including early aircraft instruments.

The company was in existence between 1893 and 1956 and continued into the 196O's with premises in the Templefields ...

5x4 camera, published with permission.

* (as editor) ''The Empire and the century: A series of essays on imperial problems and possibilities'' (190* (as translator) ''Cavalry in Future Wars'' (1906), from the German of ''Unsere Kavallerie im nächsten Kriege: Betrachtungen über ihre Verwendung, Organisation und Ausbildung'' (1899) by

Friedrich von Bernhardi

Friedrich Adam Julius von Bernhardi (22 November 1849 – 11 July 1930) was a Prussian general and military historian. He was a best-selling author prior to World War I. A militarist, he is perhaps best known for his bellicose book ''Deutschland ...

In 1905 Goldman became the founding editor of ''The Cavalry Journal''. From 1911 the editorship was an ''ex officio'' duty of the commandant of the Cavalry School at Netheravon

Netheravon is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish on the River Avon (Hampshire), River Avon and A345 road, about north of the town of Amesbury in Wiltshire, South West England. It is within Salisbury Plain.

The village is on ...

.

Mapping

* Map of the Witwatersrand goldfield, compiled 1891 from government surveys by Ewan Currey and Brian Tucker, scale 1:29,779, published 1892. * ''Atlas of the Witwatersrand and Other Goldfields in the South African Republic'' (1899), compiled under the direction of C. S. Goldmann, with Baron A. von Maltzan ( Ago von Maltzan, in the later 1890s at university in Breslau).

Legacy

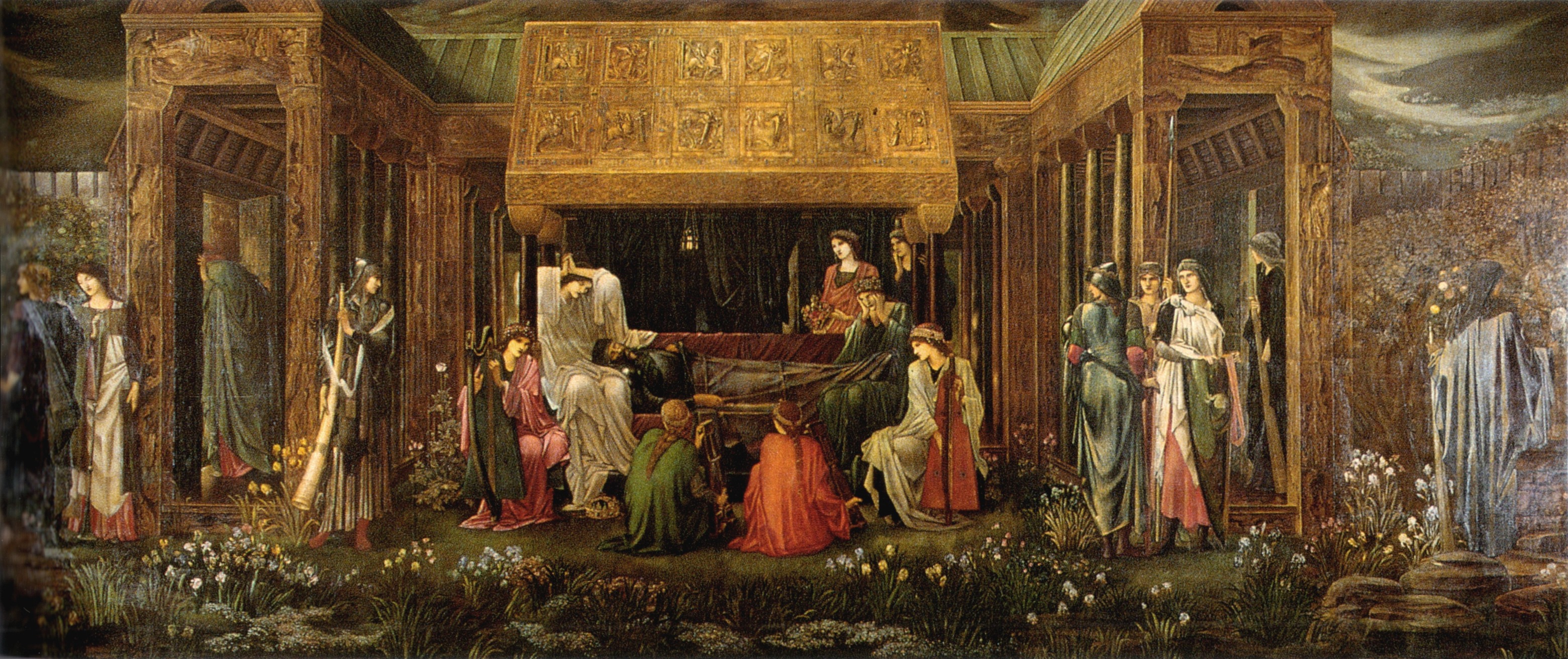

Goldman was a collector ofPre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), later known as the Pre-Raphaelites, was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossett ...

art. His pictures were divided between his two sons.

One of Goldman's legacies is

One of Goldman's legacies is Monck Provincial Park

Monck Provincial Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada, located at Nicola Lake near the town of Merritt. The park's campground is one of those which accepts reservations. Activities including fishing, camping and hiking. Natur ...

on the shore of Nicola Lake

Nicola Lake is a glacially formed narrow, deep lake located in the South-Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada approximately thirty kilometres northeast of the city of Merritt. It was a centrepoint of the first settlements in the grasslan ...

, for which Goldman gave land in 1951. There was a memorial stone to Charles Sydney Goldman in the yard at the Murray United Church in the area. The church itself was burned down in 2019.

Family

Goldman married, in 1899, the Hon. Agnes Mary Peel (1869–1959), daughter ofLiberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

politician Arthur Peel, 1st Viscount Peel

Arthur Wellesley Peel, 1st Viscount Peel, (3 August 182924 October 1912), was a British Liberal politician, who sat in the House of Commons from 1865 to 1895. He was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1884 until 1895, when he was raised to ...

. They had met when she visited the Rand

The RAND Corporation, doing business as RAND, is an American nonprofit global policy think tank, research institute, and public sector consulting firm. RAND engages in research and development (R&D) in several fields and industries. Since the ...

, and the house "Amerden" Sydney shared there with his brother Richard. During the Boer War she worked as a nurse in the military hospital at Pietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; ) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa after Durban. It was named in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. The town was named in Zulu after King ...

. She was decorated with the Royal Red Cross

The Royal Red Cross (RRC) is a military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth for exceptional services in military nursing. It was created in 1883, and the first two awards were to Florence Nightingale and Jane Cecilia Deeb ...

, and was in December 1901 appointed a ''Lady of Grace'' of the Venerable Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

The Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (), commonly known as the Order of St John, and also known as St John International, is an order of chivalry constituted in 1888 by royal charter from Queen Victoria and dedica ...

.

After Emily Hobhouse

Emily Hobhouse (9 April 1860 – 8 June 1926) was a British welfare campaigner, anti-war activist, and pacifist. She is primarily remembered for bringing to the attention of the British public, and working to change, the deprived conditions i ...

had written in ''The Contemporary Review

''The Contemporary Review'' is a British biannual, formerly quarterly, magazine. It has an uncertain future as of 2013.

History

The magazine was established in 1866 by Alexander Strahan and a group of intellectuals intent on promoting their v ...

'' about British concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

s in South Africa, and in particular about the number of Africans remaining in them, John Smith Moffat replied in the same periodical. Two months after Moffat's article, Agnes Goldmann contributed a further article on the topic. Her views included the desirability of segregation for Africans of the Transvaal.

The Goldmans had three children. Of those, Victor Robert Penryn Monk Goldman changed his surname legally to Monck, and John Goldman Monk Goldman changed his name legally to John Monk Monck, in both cases on 22 February 1939. The name Monck was stated to be the original family name.

* John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

(1908–1999), the elder son, was born at Rottingdean

Rottingdean is a village in the city of Brighton and Hove, on the south coast of England. It borders the villages of Saltdean, Ovingdean and Woodingdean, and has a historic centre, often the subject of picture postcards.

Name

The name Rotting ...

. He became a film editor at Gainsborough Pictures

Gainsborough Pictures was a British film studio based on the south bank of the Regent's Canal, in Poole Street, Hoxton in the former Metropolitan Borough of Shoreditch, east London. Gainsborough Studios was active between 1924 and 1951. The co ...

in the 1920s, and after visiting the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

joined the Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

and was an organiser for the Association of Cinematograph Television and Allied Technicians

Association may refer to:

*Club (organization), an association of two or more people united by a common interest or goal

*Trade association, an organization founded and funded by businesses that operate in a specific industry

*Voluntary associatio ...

. In 1934 he married Margaret Thesiger, daughter of the late Frederic Thesiger, 1st Viscount Chelmsford

Frederic John Napier Thesiger, 1st Viscount Chelmsford (12 August 1868 – 1 April 1933), styled the Lord Chelmsford until 1921, was a British statesman. He served as Governor of Queensland from 1905 to 1909, Governor of New South Wales from 190 ...

. That year his sister purchased the Mewstone in Plymouth Sound to give to him. Also that year he edited ''Man of Aran

''Man of Aran'' is a 1934 Irish fictional documentary ( ethnofiction) film shot, written and directed by Robert J. Flaherty about life on the Aran Islands off the western coast of Ireland. It portrays characters living in premodern condition ...

'', directed by Robert J. Flaherty

Robert Joseph Flaherty, (; February 16, 1884 – July 23, 1951) was an American filmmaker who directed and produced the first commercially successful feature-length documentary film, '' Nanook of the North'' (1922). The film made his reputati ...

. During WWII he was a film producer for the Crown Film Unit

The Crown Film Unit was an organisation within the British Government's Ministry of Information during the Second World War; until 1940, it was the GPO Film Unit. Its remit was to make films for the general public in Britain and abroad. Its outp ...

, and after the war he worked on documentaries with Sergei Nolbandov. He also farmed.

* Victor (known as Pen Goldman) published as Penryn Goldman the 1932 travel book ''To Hell and Gone'' about Australia, introduction by Wilfred Grenfell

Sir Wilfred Thomason Grenfell (28 February 1865 – 9 October 1940) was a British medical missionary to Newfoundland, who wrote books on his work and other topics.

Early life and education

He was born at Parkgate, Cheshire, England, on 28 F ...

. He was an RNVR

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) is one of the two Volunteer Reserves (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve forces of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Together with the Royal Marines Reserve, they form the Maritime Reserve (United Kingdom), ...

officer, a temporary lieutenant on HMS ''Buxton'' in 1942, and as Lieutenant Commander sent to Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

to liaise with the US Navy in 1944 (reported by the International Grenfell Association

The International Grenfell Association (IGA) was an organization founded by Sir Wilfred Grenfell to provide health care, education, religious services, and rehabilitation and other social activities to the fisherman and coastal communities in nort ...

magazine). In later life he was often known as Commander Penryn Monck. He married in 1949 (Isolde) Sheila Tower Butler, sister of Patrick Theobald Tower Butler, 18th Baron Dunboyne .

* Hazel, the daughter, carried the train of Una Duval, first cousin of her mother, at her 1912 "suffragist" wedding, the marriage vows

Marriage vows are promises each partner in a couple makes to the other during a wedding ceremony based upon Western Christian norms. They are not universal to marriage and not necessary in most legal jurisdictions. They are not even universa ...

omitting "to obey". At the time of her giving Mewstone to her brother John and wife Margaret in 1934 as a wedding present, she was living at Sydney Lodge, Hamble-le-Rice

Hamble-le-Rice, commonly known as Hamble, is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Eastleigh (borough), Borough of Eastleigh in Hampshire, England. It is best known for being a flying training centre during the Second Wor ...

, designed by Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor of architecture at the Ro ...

. It was sold by her father in 1936.

The Goldmans also had as ward Lorna Goldman(n), daughter of Sydney's brother Edwin, after his death in 1913. She met and then married Stewart Gore-Browne

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Stewart Gore-Browne (3 May 1883 – 4 August 1967), called Chipembele by Zambians, was a British soldier, pioneer white settler, builder, politician and supporter of independence in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).

Ea ...

in 1927, at age 19 and still at Sherborne School for Girls

Sherborne Girls, formally known as Sherborne School for Girls, is an independent day and boarding school for girls, located in Sherborne, North Dorset, England. There were 485 pupils attending in 2019–2020, with more than 90 per cent of them ...

. Gore-Browne's biographer comments that "The Goldmans travelled incessantly, to the Continent and the Orient".

References

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Goldman, Sydney 1868 births 1958 deaths Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Penryn and Falmouth UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Royal Garrison Artillery officers British Army personnel of World War I Cape Colony people South African emigrants to the United Kingdom South African people of German-Jewish descent Jewish British politicians Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society