Charles Sidney Gilpin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

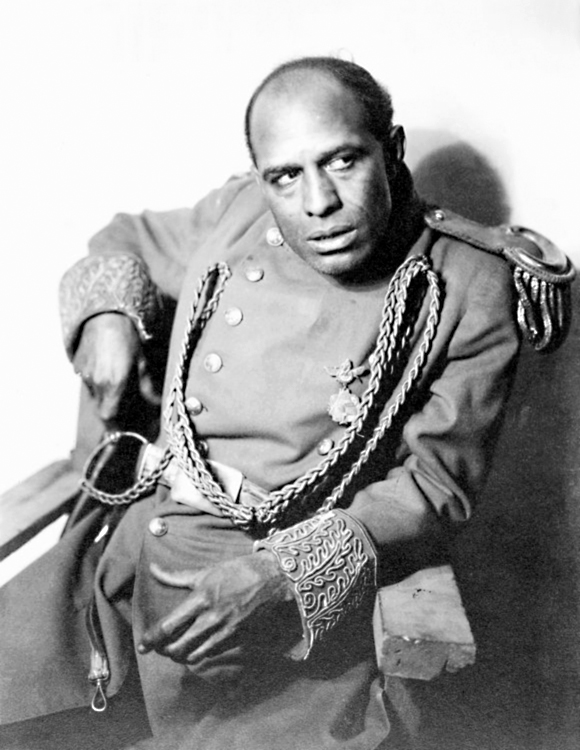

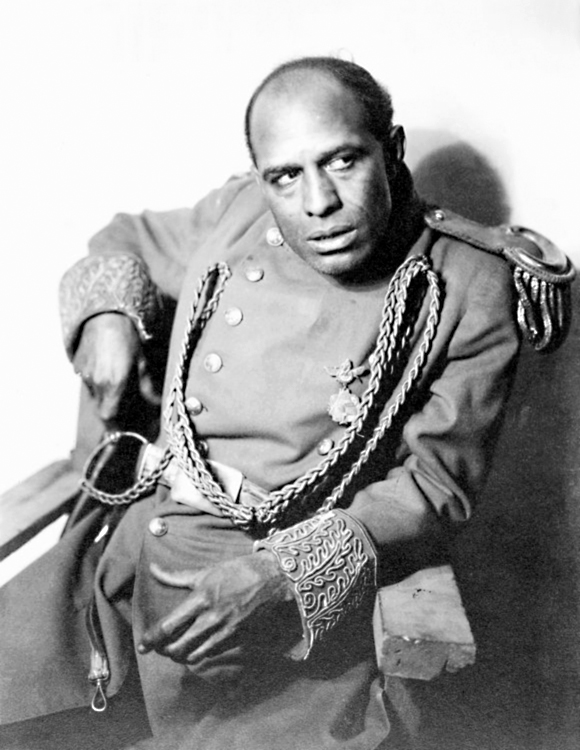

Charles Sidney Gilpin (November 20, 1878 – May 6, 1930) was a stage actor of the 1920s. He played in two New York City debuts: the 1919 premier of John Drinkwater's ''

In 1896 at the age of 18, Gilpin joined a

In 1896 at the age of 18, Gilpin joined a

"On Stage, and Off"

''The New York Times''. December 6, 1991.

"Charles Gilpin Comments. Striving to Present His Art Rather Than Himself to Public, Says Negro"

''The New York Times'', February 19, 1921.

"The New Plays"

''The New York Times'', December 26, 1920.

"News and Gossip of the Rialto"

''The New York Times'', October 24, 1920.

"Don Quixote Back to Life"

''The New York Times'', May 7, 1920

"'Emperor Jones' Coming Uptown"

''The New York Times'', December 13, 1920.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

'' and the lead role of Brutus Jones in the 1920 premiere of Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of Realism (theatre), realism, earlier associated with ...

's ''The Emperor Jones

''The Emperor Jones'' is a 1920 tragic play by American dramatist Eugene O'Neill that tells the tale of Brutus Jones, a resourceful, self-assured African American and a former Pullman porter, who kills another black man in a dice game, is jailed ...

'' (he later toured this play). In 1920, he was the first black person to receive The Drama League

The Drama League is an American theatrical association based in New York City. The organization was founded in 1910, in Chicago, as the Drama League of America, and chapters were established throughout the United States. In 1911, the organization b ...

's annual award as one of ten people who had done the most that year for American theatre. He also appeared in films.

Early life and education

Gilpin was born inRichmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, to Peter Gilpin (a factory worker) and Caroline White (a nurse);"Charles Gilpin Buried After Simple Services in Trenton Baptist Church." ''Amsterdam (NY) News'', May 14, 1930, p. 1. he attended St. Francis School for Colored Children in that city. He started work as an apprentice in the ''Richmond Planet

''The Richmond Planet'' was an African American newspaper founded in 1882 in Richmond, Virginia. In 1938, it merged with the '' Richmond Afro-American''.

History

The paper was founded in 1882 by thirteen former slaves - James H. Hayes, James ...

'' print shop before finding his career in theater. He first performed on stage as a singer at the age of 12. Prior to becoming a stage actor full-time, he worked as a printer and a pressman at several black newspapers during the late 1880s and into the 1890s, while getting some part-time work in vaudeville. He married Florence Howard in 1897, and they had one son.

Career

In 1896 at the age of 18, Gilpin joined a

In 1896 at the age of 18, Gilpin joined a minstrel show

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of portraying racial stereotypes of Afr ...

, leaving Richmond and beginning a life on the road that lasted for many years. When between performances on stage, like many performers, he worked odd jobs to earn money: as a printer

Printer may refer to:

Technology

* Printer (publishing), a person

* Printer (computing), a hardware device

* Optical printer for motion picture films

People

* Nariman Printer (fl. c. 1940), Indian journalist and activist

* James Printer (1640 ...

, barber

A barber is a person whose occupation is mainly to cut, dress, groom, style and shave hair or beards. A barber's place of work is known as a barbershop or the barber's. Barbershops have been noted places of social interaction and public discourse ...

, boxing trainer, and railroad porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., a locom ...

. In 1903, he joined Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario. Hamilton has a 2021 Canadian census, population of 569,353 (2021), and its Census Metropolitan Area, census metropolitan area, which encompasses ...

's Canadian Jubilee Singers

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are an African-American a cappella ensemble, consisting of students at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The first group was organized in 1871 to tour and raise funds for college. Their early repertoire consisted ...

.

In 1905, he started performing with traveling musical troupes of the Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

and the Candy Shop of America. He also played his first dramatic roles and honed his character acting in Chicago. He performed with Robert T. Motts' Pekin Theater in Chicago for four years until 1911. Soon after, he toured the United States with the Pan-American Octetts. Gilpin worked with Rogers and Creamer's Old Man's Boy Company in New York. In 1915, Gilpin joined the Anita Bush Players, led by Anita Bush, as they moved from the Lincoln Theater in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

to the Lafayette Theatre. As New York theater was expanding, this was a time when the theatrical careers of many famous black actors were launched.

In 1916, Gilpin made a memorable appearance in whiteface as Jacob McCloskey, a slave owner and villain of Dion Boucicault

Dionysius Lardner "Dion" Boucicault (né Boursiquot; 26 December 1820 – 18 September 1890) was an Irish actor and playwright famed for his melodramas. By the later part of the 19th century, Boucicault had become known on both sides of the ...

's ''The Octoroon''. Though Gilpin left Bush's company over a salary dispute, his reputation allowed him to get the role of Rev. William Curtis in the 1919 premier of John Drinkwater's ''Abraham Lincoln''.

Gilpin's Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

debut led to his being cast in the premier of Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of Realism (theatre), realism, earlier associated with ...

's ''The Emperor Jones

''The Emperor Jones'' is a 1920 tragic play by American dramatist Eugene O'Neill that tells the tale of Brutus Jones, a resourceful, self-assured African American and a former Pullman porter, who kills another black man in a dice game, is jailed ...

''. He played the lead role of Brutus Jones to great critical acclaim, including a lauded review by writer Hubert Harrison

Hubert Henry Harrison (April 27, 1883 – December 17, 1927) was a West Indian-American writer, orator, educator, critic, race and class conscious political activist, and radical internationalist based in Harlem, New York. He was described by a ...

in ''Negro World

''Negro World'' was the newspaper of the Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA). Founded by Garvey and Amy Ashwood Garvey, the newspaper was published weekly in Harlem, and distributed int ...

''. Gilpin's achievement resulted in The Drama League

The Drama League is an American theatrical association based in New York City. The organization was founded in 1910, in Chicago, as the Drama League of America, and chapters were established throughout the United States. In 1911, the organization b ...

's naming him as one of the 10 people in 1920 who had done the most for American theater. He was the first black American so honored. Following the Drama League's refusal to rescind the invitation, Gilpin refused to decline it. When the League invited Gilpin to their presentation dinner, some people found it controversial. At the dinner, he was given a standing ovation of unusual length when he accepted his award. Although Gilpin continued to perform the role of Brutus Jones in the U.S. tour that followed the Broadway closing of the play, he had a falling-out with O'Neill. Gilpin wanted O'Neill to remove the word "nigger", which occurred frequently in the play. The playwright refused, asserting its use was consistent with his dramatic intentions.

In 1921, Gilpin was awarded the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

's Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for an outstanding achievement by an African Americans, African American. The award was created in 1914 by Joel Elias Spingarn, ...

. He was also honored at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

by President Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

. A year later, the Dumas Dramatic Club (now the Karamu Players) of Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

renamed itself the Gilpin Players in his honor.

When they could not come to a reconciliation, O'Neill replaced Gilpin with Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

as Brutus Jones in the London production.

In early April 1922, Gilpin became one of the first black performers to give a dramatic presentation on radio. He gave readings from "The Emperor Jones" over greater Boston station WGI, from their Medford Hillside studios.

After the extended controversy and the disappointment of losing his signature role, Gilpin started drinking heavily. He never again performed on Broadway. He died in 1930 in Eldridge Park, New Jersey, his career in shambles. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Woodlawn Cemetery Woodlawn Cemetery is the name of several cemeteries, including:

Canada

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Saskatoon)

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Nova Scotia)

United States

''(by state then city or town)''

* Woodlawn Cemetery (Ocala, Florida), where Isaac Rice and fa ...

in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, his funeral arranged by friends shortly after his death.

In 1991, 61 years after his death, Gilpin was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame

The American Theater Hall of Fame was founded in 1972 in New York City. The first head of its executive committee was Earl Blackwell. In an announcement in 1972, he said that the new ''Theater Hall of Fame'' would be located in the Uris Theatre, ...

.

Relationship with Eugene O'Neill

O'Neill had major influence on African American actors, in particular Gilpin andPaul Leroy Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

. O'Neill and Robeson worked on three productions together: ''All God's Chillun Got Wings'' (1924), ''The Emperor Jones

''The Emperor Jones'' is a 1920 tragic play by American dramatist Eugene O'Neill that tells the tale of Brutus Jones, a resourceful, self-assured African American and a former Pullman porter, who kills another black man in a dice game, is jailed ...

'' (1924), and ''The Hairy Ape

''The Hairy Ape'' is a 1922 expressionist play by American playwright Eugene O'Neill. It is about a beastly, unthinking laborer known as Yank, the protagonist of the play, as he searches for a sense of belonging in a world controlled by the ri ...

'' (1931). Gilpin was the first actor to play the role of Emperor Jones when it was first staged on November 1, 1920, by the Provincetown Players at the Playwright's Theater in New York City. This production was O'Neill's first real smash hit. The Players' small theater was too small to cope with audience demand for tickets, and the play was transferred to another theater. It ran for 204 performances and was hugely popular, and toured in the States with this cast for the next two years. Gilpin continued to perform the role of Brutus Jones in the U.S. tour that followed the Broadway closing of the play, and in 1920 became the first black American to receive the Drama League of New York's annual award as one of the ten people who had done the most that year for American theater. The following year Gilpin was awarded the NAACP's Spingarn Medal. He was also honored at the White House by president Warren G. Harding. A year later, the Dumas Dramatic Club (now the Karamu Players) of Cleveland renamed itself the Gilpin Players in his honor. Though the acclaimed actor continued to perform in subsequent productions of the play, he eventually had a falling-out with O'Neill who argued with Gilpin's tendency to change his use of the word "nigger" to "Negro" and "colored" during performances. Gilpin wanted O'Neill to remove the word "nigger" from the play altogether, which occurred frequently in the play, but the playwright refused, arguing its use was consistent with his dramatic intentions and that the use of language was, in fact, based on a friend, an African-American tavern-keeper on the New London waterfront that was O'Neill's favorite drinking spot in his home town. When they could not come to a reconciliation, O'Neill replaced the middle-aged Gilpin with the much younger and then unknown Paul Robeson, who had only performed on the concert stage. Robeson starred in the title role in the 1924 New York revival and in the London production.

In 1924 he was in ''Dixie to Broadway'' and in 1925 he was in the play ''So That's That'' by Joseph Byron Totten.

He received excellent reviews and, coupled with his performance in the 1928 London production of the musical ''Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical theatre, musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 Show Boat (novel), novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the per ...

'', went on to worldwide fame as one of the great artists of the 20th century. The show was again revived in 1926 at the Mayfair Theatre in Manhattan, with Gilpin again starring as Jones and also directing the show. The production, which ran for 61 performances, is remembered today for the acting debut of a young Moss Hart as Smithers and broke social barriers and defied conventions of the day as the first American play to feature an African-American central character portrayed in a serious manner. The play was adapted for a 1933 feature film starring Paul Robeson, directed by Dudley Murphy, an avant-garde filmmaker of O'Neill's Greenwich Village circle who pursued the reluctant playwright for a decade before getting the rights from him. Gilpin continued to make a small living performing monologues from O'Neill's play at church gatherings, but after the extended controversy and the disappointment of losing his signature role, succumbed to depression and began drinking heavily. He never again performed on Broadway and died in 1930 in Eldridge Park, New Jersey, his career in shambles. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, his funeral arranged by friends shortly after his death. In recognition of his groundbreaking work, Gilpin was posthumously inducted into the American Theatre Hall of Fame

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

in 1991.''The New York Times''. December 6, 1991.

Further reading

"Charles Gilpin Comments. Striving to Present His Art Rather Than Himself to Public, Says Negro"

''The New York Times'', February 19, 1921.

"The New Plays"

''The New York Times'', December 26, 1920.

"News and Gossip of the Rialto"

''The New York Times'', October 24, 1920.

"Don Quixote Back to Life"

''The New York Times'', May 7, 1920

"'Emperor Jones' Coming Uptown"

''The New York Times'', December 13, 1920.

References

Sources

* Henry T. Sampson ''The Ghost Walks: A Chronological History of Blacks in Show Business 1865–1910'', (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1988), p. 321. * "Charles Sidney Gilpin", ''Dictionary of American Biography'', American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936. * John T. Kneebone, "'It Wasn't All Velvet': The Life and Hard Times of Charles S. Gilpin, Actor", ''Virginia Cavalcade'', 38 (summer 1988): 14–27.External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gilpin, Charles Sidney 1878 births 1930 deaths Blackface minstrel performers American vaudeville performers 20th-century African-American male actors 20th-century American male actors Male actors from Richmond, Virginia