Charles Samson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Samson took part in several early naval aviation experiments, including the development of

Samson took part in several early naval aviation experiments, including the development of

When the First World War broke out, Samson took the Eastchurch RNAS Squadron to France, where it supported Allied ground forces along the French and Belgian frontiers. In the late summer of 1914, with too few aircraft at his disposal, Samson instead had his men patrol the French and Belgian countryside in the privately owned cars some of them had taken to war. The first patrol comprised two cars, nine men, and one machine gun. Inspired by the success of the Belgians' experience of armoured cars, Samson had two RNAS cars, a Mercedes and a Rolls-Royce, armoured. These vehicles had only partial protection, with a single machine gun firing backwards, and were the first British armoured vehicles to see action. Within a month most of Samson's cars had been armed and some armoured. These were joined by further cars which had been armoured in Britain with hardened steel plates at Royal Navy workshops. The force was also equipped with some trucks which had been armoured and equipped with loopholes so that the

When the First World War broke out, Samson took the Eastchurch RNAS Squadron to France, where it supported Allied ground forces along the French and Belgian frontiers. In the late summer of 1914, with too few aircraft at his disposal, Samson instead had his men patrol the French and Belgian countryside in the privately owned cars some of them had taken to war. The first patrol comprised two cars, nine men, and one machine gun. Inspired by the success of the Belgians' experience of armoured cars, Samson had two RNAS cars, a Mercedes and a Rolls-Royce, armoured. These vehicles had only partial protection, with a single machine gun firing backwards, and were the first British armoured vehicles to see action. Within a month most of Samson's cars had been armed and some armoured. These were joined by further cars which had been armoured in Britain with hardened steel plates at Royal Navy workshops. The force was also equipped with some trucks which had been armoured and equipped with loopholes so that the  From November 1917 until the end of the War, Samson was in command of an aircraft group at

From November 1917 until the end of the War, Samson was in command of an aircraft group at

Air of Authority – A History of RAF Organisation – Air Commodore C R SamsonOxford Dictionary of National Biography – Samson, Charles Rumney

A 1915 photograph of Charles Samson

taken at Gallipoli (image not available as of September 2022)

Felixstowe, Suffolk: Pioneering Sea Plane Base

Audio recording of George Edward Brice who recalls Charles Rumney Samson testing a seaplane during the First World War.

58ft Towing Lighters

Information and photographs on seaplane lighters including Samson's test flight and Culley's attack on Zeppellin L53.

Flying boats

over the

Air Commodore

Air commodore (Air Cdre or Air Cmde) is an air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes ...

Charles Rumney Samson, (8 July 1883 – 5 February 1931) was a British naval aviation

Naval aviation / Aeronaval is the application of Military aviation, military air power by Navy, navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

It often involves ''navalised aircraft'', specifically designed for naval use.

Seab ...

pioneer. He was one of the first four officers selected for pilot training by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and was the first person to fly an aircraft from a moving ship. He also commanded the first British armoured vehicles

Military vehicles are commonly armoured (or armored; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) to withstand the impact of Fragmentation (weaponry), shrapnel, bullets, Shell (projectile), shells, Rocke ...

used in combat. Transferring to the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

on its creation in 1918, Samson held command of several groups in the immediate post-war period and the 1920s.

Early life

Samson was born inCrumpsall

Crumpsall is an outer suburb and Wards of the United Kingdom, electoral ward of Manchester, in Greater Manchester, England, north of Manchester city centre, bordered by Cheetham Hill, Blackley, Harpurhey, Broughton, Greater Manchester, Broughton ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, on 8 July 1883, the son of Charles Leopold Samson, a solicitor

A solicitor is a lawyer who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and enabled to p ...

, and his wife Margaret Alice (née Rumney). 1891 Census of Salford, RG12/3214, Folio 160, Page 27, Charles R Samson, Carmona, Cavendish Road, Broughton, Salford.

Early naval career

Samson entered HMS ''Britannia'' as a cadet in 1896, before becoming amidshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in 1898. In the 1901 Census he is listed as a midshipman aboard the battleship HMS ''Victorious''. He was promoted Sub-Lieutenant in 1902 and the following year served on HMS ''Pomone'' in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

and Somaliland

Somaliland, officially the Republic of Somaliland, is an List of states with limited recognition, unrecognised country in the Horn of Africa. It is located in the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, E ...

. He was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

on 30 September 1904 while serving as an officer on boys' training ships.

In 1906 Samson was appointed Officer Commanding of Torpedo Boat No. 81 and in February 1908 he was posted to HMS ''Commonwealth''. The following year he was appointed first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

on HMS ''Philomel'' serving in the Persian Gulf and in the autumn of 1910 he transferred to HMS ''Foresight'', again serving as the ship's First Lieutenant.

Naval aviation

In 1911 he was selected as one of the first four Royal Navy officers to receive pilot training, and obtained hisRoyal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

certificate

Certificate may refer to:

* Birth certificate

* Marriage certificate

* Death certificate

* Gift certificate

* Certificate of authenticity, a document or seal certifying the authenticity of something

* Certificate of deposit, or CD, a financial p ...

on 25 April 1911, after only 71 minutes flying time, at a RAeC meeting that also awarded licences to the pioneer naval aviators Wilfred Parke and Arthur Longmore

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Murray Longmore, (8 October 1885 – 10 December 1970) was an early naval aviator, before reaching high rank in the Royal Air Force. He was Commander-in-Chief of the RAF's Middle East Command from 1940 to 1941.

E ...

. He completed flying training at Eastchurch

Eastchurch is a village and civil parish on the Isle of Sheppey, in the English county of Kent, two miles east of Minster, Swale, Minster. The village website claims the area has "a history steeped in stories of piracy and smugglers".

Aviation ...

before being appointed Officer Commanding Naval Air Station Eastchurch in October 1911. In January 1912 he was promoted to acting Commander. The following April he was appointed Officer Commanding the Naval Flying School at Eastchurch.

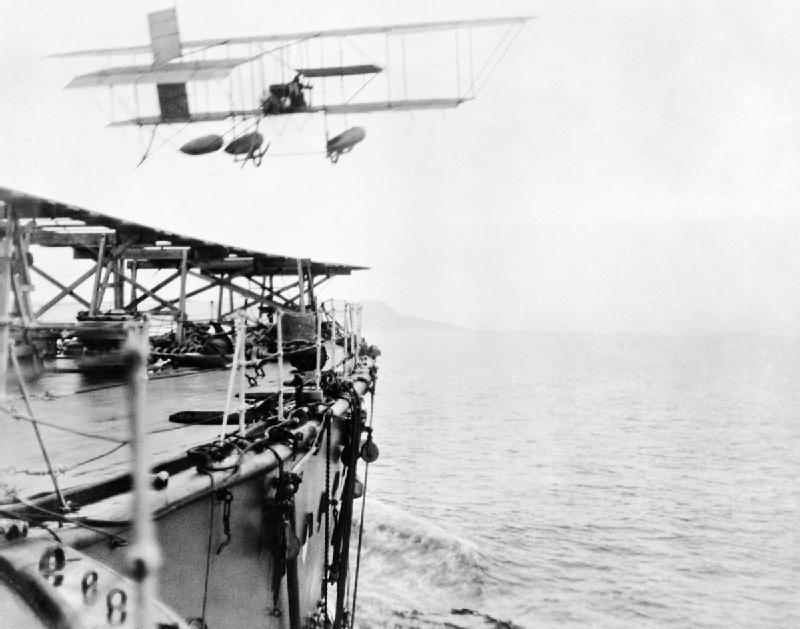

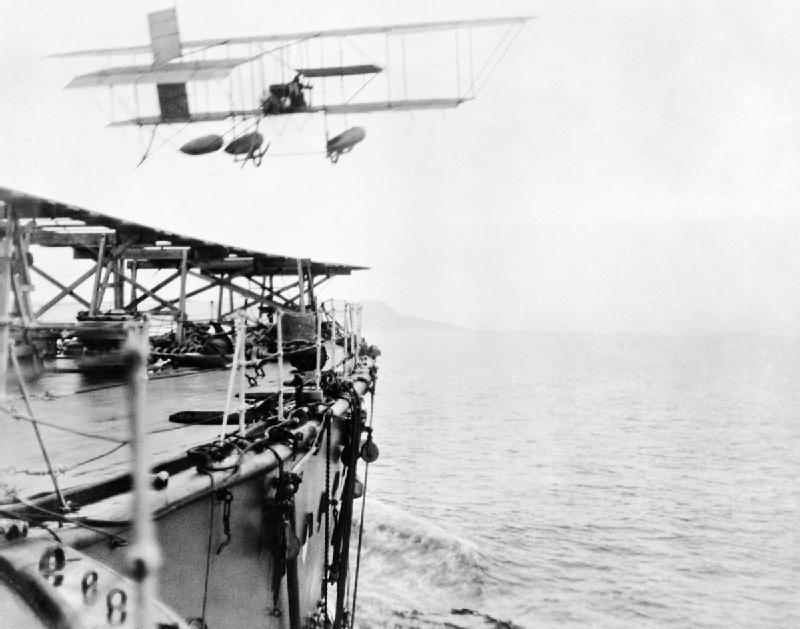

Samson took part in several early naval aviation experiments, including the development of

Samson took part in several early naval aviation experiments, including the development of navigation light

A navigation light, also known as a running or position light, is a source of illumination on a watercraft, aircraft or spacecraft, meant to give information on the craft's position, heading, or status. Some navigation lights are colour-code ...

s and bomb sights. He was the first British pilot to take off from a ship, on 10 January 1912, flying a Short Improved S.27 from a ramp mounted on the foredeck of the battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

HMS ''Africa'', which was at anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal, used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ', which itself comes from the Greek ().

Anch ...

in the river Medway

The River Medway is a river in South East England. It rises in the High Weald AONB, High Weald, West Sussex and flows through Tonbridge, Maidstone and the Medway conurbation in Kent, before emptying into the Thames Estuary near Sheerness, a to ...

. On 9 May 1912 he became the first pilot to take off from a moving ship, using the same ramp and aircraft, now fitted to the battleship HMS ''Hibernia'' during the 1912 Naval Review

A Naval Review is an event where select vessels and assets of the United States Navy are paraded to be reviewed by the President of the United States or the Secretary of the Navy. Due to the geographic distance separating the modern U.S. Na ...

in Weymouth Bay. He repeated the feat on 4 July 1912, this time from the battleship HMS ''London'' while ''London'' was under way.

When the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

was formed in May 1912 Samson took command of its Naval Wing, and led the development of aerial wireless communications, bomb and torpedo-dropping, navigational techniques, and night flying.

In 1914 the Royal Navy separated the Naval Wing from the Royal Flying Corps, naming it the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

(RNAS). In July Samson was appointed Officer Commanding the Eastchurch (Mobile) Squadron which was renamed No. 3 Squadron RNAS by September 1914.

In 1914, while Samson was in command of the Royal Naval Air Station at Eastchurch, he led a flight in the Naval Review

A Naval Review is an event where select vessels and assets of the United States Navy are paraded to be reviewed by the President of the United States or the Secretary of the Navy. Due to the geographic distance separating the modern U.S. Na ...

at Spithead. In an effort to increase the popularity of flying in the navy, Samson had his pilots offer rides to anyone who was interested.

First World War

When the First World War broke out, Samson took the Eastchurch RNAS Squadron to France, where it supported Allied ground forces along the French and Belgian frontiers. In the late summer of 1914, with too few aircraft at his disposal, Samson instead had his men patrol the French and Belgian countryside in the privately owned cars some of them had taken to war. The first patrol comprised two cars, nine men, and one machine gun. Inspired by the success of the Belgians' experience of armoured cars, Samson had two RNAS cars, a Mercedes and a Rolls-Royce, armoured. These vehicles had only partial protection, with a single machine gun firing backwards, and were the first British armoured vehicles to see action. Within a month most of Samson's cars had been armed and some armoured. These were joined by further cars which had been armoured in Britain with hardened steel plates at Royal Navy workshops. The force was also equipped with some trucks which had been armoured and equipped with loopholes so that the

When the First World War broke out, Samson took the Eastchurch RNAS Squadron to France, where it supported Allied ground forces along the French and Belgian frontiers. In the late summer of 1914, with too few aircraft at his disposal, Samson instead had his men patrol the French and Belgian countryside in the privately owned cars some of them had taken to war. The first patrol comprised two cars, nine men, and one machine gun. Inspired by the success of the Belgians' experience of armoured cars, Samson had two RNAS cars, a Mercedes and a Rolls-Royce, armoured. These vehicles had only partial protection, with a single machine gun firing backwards, and were the first British armoured vehicles to see action. Within a month most of Samson's cars had been armed and some armoured. These were joined by further cars which had been armoured in Britain with hardened steel plates at Royal Navy workshops. The force was also equipped with some trucks which had been armoured and equipped with loopholes so that the Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

carried in them could fire their rifles in safety. This was the start of the RNAS Armoured Car Section.

Aggressive patrolling by Samson's improvised force in the area between Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

and Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

did much to prevent German cavalry divisions from carrying out effective reconnaissance, and with the help of Belgian Post Office employees who used the intact telephone system to report German movements, he was able to probe deeply into German-occupied territory. Closer to Dunkirk, Samson's force assisted Allied units in contact with the Germans, and at other times made use of their mobility and machine guns to exploit open flanks, cover retreats, and race German forces to important areas.

Samson's aircraft also bombed the Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

sheds at Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in the state after Cologne and the List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants, seventh-largest city ...

and Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, and by the end of 1914, when mobile warfare on the Western Front ended and trench warfare took its place, his squadron had been awarded four Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

s, among them his own, and he was given a special promotion and the rank of commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

. He spent the next few months bombing gun positions, submarine depots, and seaplane sheds on the Belgian coast.

In March 1915 Samson was sent to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

with No 3 Squadron (later No 3 Wing); it was based on the island of Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos''; ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

and, together with seaplanes from HMS ''Ark Royal'', initially provided the only Allied air cover. On arrival, it was found that out of 30 aircraft that had been sent in crates, only 5 were serviceable ( B.E.2s and a Nieuport 10

The Nieuport 10 (or Nieuport XB in contemporary sources) is a French First World War sesquiplane that filled a wide variety of roles, including reconnaissance, fighter and trainer.

Design and development

In January 1914, designer joined the '' ...

). His squadron pioneered the use of radio in directing the fire of battleships and photo-reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting, the collection of imag ...

. Samson flew many missions himself and on 25 April at the Landing at Cape Helles, he reported that "the sea was absolutely red with blood to 50 yards out" at ''Sed-el-Barr'' ("V Beach"). On 27 May, Samson attacked the German submarine ''U-21'', which had just sunk ; when he ran out of bombs he resorted to firing his rifle

A rifle is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting and higher stopping power, with a gun barrel, barrel that has a helical or spiralling pattern of grooves (rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus o ...

at it. In June, a temporary airstrip was constructed at Cape Helles; Samson became well known for waving cheerily to the Allied troops in the trenches below. On one occasion, he bombed a Turkish staff car but only succeeded in breaking the windscreen; one of the occupants was Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa () is one of the names of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Moustafa

* Moustafa A ...

, the charismatic Turkish commander and later founder of the Turkish Republic. In August, Samson's wing was moved to a new airfield at Imbros

Imbros (; ; ), officially Gökçeada () since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchang ...

where it was joined by No 2 Wing under the overall command of Colonel Frederick Sykes

Sir Frederick Hugh Sykes (23 July 1877 – 30 September 1954) was a British military officer and politician.

Sykes was a junior officer in the 15th Hussars before becoming interested in military aviation. He was the first Officer Commanding t ...

. who had been given the naval rank of Wing Captain with three years' seniority. Sykes had previously written a critical report of the Gallipoli air operations, which had caused Samson to lobby against Sykes; however, Samson loyally served under Sykes until he was recalled to London in November.

On 14 May 1916, Samson was given command of , a former Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

passenger steamer which had been converted into a seaplane carrier. Based at Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

, he patrolled the coasts of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, sending his aircraft on reconnaissance missions and bombing Turkish positions, often flying himself on operations. On 2 June, Samson took his ship through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

to Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

, where he personally led a six-day bombing campaign. After silencing Turkish guns at Perim

Perim (), also called Mayyun () in Arabic, is a Yemeni volcanic island in the Strait of Mandeb at the south entrance into the Red Sea, off the south-west coast of Yemen. It administratively belongs to Dhubab District or Bab al-Mandab District ...

, ''Ben My Chree'' headed to Jidda where on 15 June, her aircraft operated in support of an attack by Arab forces led by Faisal, son of Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Qatadah branch of the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after proclaiming the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Em ...

; Samson lost the heel of his boot as well as various pieces of his seaplane to ground fire. The Turks surrendered the next day. Further operations off the coast of Palestine followed; on 26 July, Samson and his observer, Lieutenant Wedgewood Benn destroyed a train carrying 1,600 troops with a 16 lb bomb. In almost continuous action through the rest of 1916, Samson received a signal from the Admiralty asking why ''Ben-my-Chree'' had used so much ammunition; he replied "that there was unfortunately a war on". In January 1917 he sailed to Castellorizo to carry out joint operations with the French, and in the harbour there the ''Ben My Chree'' was sunk on 11 January by Turkish gunfire. A subsequent Court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

acquitted Samson and the crew of all responsibility and commended them for their behaviour. His two escort ships, already equipped to carry a few seaplanes, were fitted out for independent air operations, and from Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

and later Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

, he patrolled the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

for enemy commerce raiders.

From November 1917 until the end of the War, Samson was in command of an aircraft group at

From November 1917 until the end of the War, Samson was in command of an aircraft group at Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth ( ), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside resort, seaside town which gives its name to the wider Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. Its fishing industry, m ...

responsible for anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin operations over the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, during which time his group shot down five Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

s. In order to bring fighter aircraft into action near the enemy coasts, he developed with John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Colonel John Cyril Porte, (26 February 1884 – 22 October 1919) was a British flying boat aviation pioneer, pioneer associated with the First World War Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.

Early life and career

Porte was b ...

an adapted seaplane lighter

A lighter is a portable device which uses mechanical or electrical means to create a controlled flame, and can be used to ignite a variety of flammable items, such as cigarettes, butane gas, fireworks, candles, or campfires. A lighter typic ...

which could be towed behind naval vessels and used as a take-off platform by fighter aircraft. This system led to the destruction of Zeppelin L53 on 11 August 1918 by Lieutenant S. D. Culley, who was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

. The Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the b ...

flown by Culley in the attack can be seen at the Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum (IWM), currently branded "Imperial War Museums", is a British national museum. It is headquartered in London, with five branches in England. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, it was intended to record the civ ...

.

In October 1918 the group became 73 Wing of the new No. 4 Group based at the Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe as part of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. Samson became commanding officer of this group, and in August 1919 gave up his naval commission and received instead a permanent commission in the RAF with the rank of Group Captain

Group captain (Gp Capt or G/C) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many Commonwealth of Nations, countries that have historical British influence.

Group cap ...

.

Marriage

Samson was married inColombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

on 7 April 1917 to Miss Honor Oakden Patrickson Storey, the only daughter of Herbert Lushington Storey, and his wife, Emily Muriel Storey. They had one daughter.

Samson was granted a decree nisi

A decree nisi or rule nisi () is a court order that will come into force at a future date unless a particular condition is met. Unless the condition is met, the ruling becomes a decree absolute (rule absolute), and is binding. Typically, the con ...

against his wife by the Divorce Court in London in December 1923. Their divorce became final in 1924.

He was married again, in 1924, to Winifred Reeves, the daughter of Mr and Mrs Herbert K. Reeves, who survived him. They had two children, John Louis Rumney born 19 June 1925 and Priscilla Rumney born after her father's death on 24 March 1931.

Postwar

During 1920 Samson served as Chief Staff Officer in the Coastal Area, and in 1921 became Air Officer Commanding for RAF units in the Mediterranean, based atMalta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

. In 1922 he was promoted to air commodore

Air commodore (Air Cdre or Air Cmde) is an air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes ...

and given command of 6 Fighter Group at RAF Kenley

Royal Air Force Kenley, more commonly known as RAF Kenley, is a former List of former Royal Air Force stations, station of the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War and the Royal Air Force, RAF in the Second World War. It played a significa ...

(S London).

In June 1926 he became Chief Staff Officer of the RAF's Middle East Command, in September 1926 he led a flight from Cairo to Aden: the flight left Cairo on 15 September 1926 and was flown by two Vickers Victoria biplanes and returned to Cairo on 29 September. He later flew an RAF formation of four Fairey III biplanes from Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

to the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

. He remained with the Middle East command until August 1927.

Samson was placed on the retired list on account of ill health in 1929 and died of heart failure at his home near Salisbury, Wiltshire, on 5 February 1931. He was buried at Putney Vale Cemetery

Putney Vale Cemetery and Crematorium in southwest London is located in Putney Vale, surrounded by Putney Heath and Wimbledon Common and Richmond Park. It is located within of parkland. The cemetery was opened in 1891 and the crematorium in 193 ...

on 10 February.

Honours and awards

*21 October 1914 –Companion of the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful command and leadership during active operations, typicall ...

in recognition for service between 1 September and 5 October 1914 in command of the Aeroplane and Armoured Motor Support of the Royal Naval Air Service at Dunkirk.

*1914 – Croix de guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

(France)

*1915 – Knight of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and civil. Currently consisting of five classes, it was ...

(France)

*14 March 1916 – Mention in Despatches for service in action during the landing and evacuation on the Gallipoli peninsula.

*23 January 1917 – Bar to the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

for continued gallantry as a Flying Officer.

*1 January 1919 – Air Force Cross

*3 June 1919 – Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George I ...

in recognition of distinguished service during the war.

See also

*List of firsts in aviation

This is a list of firsts in aviation. For a comprehensive list of women's records, see Women in aviation.

First person to fly

The first flight (including gliding) by a person is unknown. A number have been suggested:

* In 559 A.D., several pr ...

*Eugene Burton Ely

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886 – October 19, 1911) was an American aviator, aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft takeoff and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa, and raised in Davenport, Iowa. H ...

, the first pilot to take off from a ship and land on a ship

* Mustafa Ertuğrul Aker, the first officer to sink an aircraft carrier

* Force Z#Origins.2C Destruction.2C Vindication, on Samson's unheeded warnings

References

Bibliography

* * *Air of Authority – A History of RAF Organisation – Air Commodore C R Samson

External links

* A 1913 photograph of Samson and Cecil Malone with other pioneering officers of the RFCA 1915 photograph of Charles Samson

taken at Gallipoli (image not available as of September 2022)

Felixstowe, Suffolk: Pioneering Sea Plane Base

Audio recording of George Edward Brice who recalls Charles Rumney Samson testing a seaplane during the First World War.

58ft Towing Lighters

Information and photographs on seaplane lighters including Samson's test flight and Culley's attack on Zeppellin L53.

Flying boats

over the

Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (, ) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends from the mouth of the Elb ...

: Article exploring the use of seaplane lighters in combined operations with the Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, it ...

.

, -

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Samson, Charles Rumney

1883 births

1931 deaths

Royal Air Force air commodores

Royal Navy officers

British aviation pioneers

19th-century Royal Navy personnel

Royal Naval Air Service aviators

Royal Air Force personnel of World War I

Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom)

Knights of the Legion of Honour

Royal Navy officers of World War I

Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

British recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

Military personnel from Manchester