Charles Inglis (engineer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Charles Edward Inglis (; 31 July 1875 – 19 April 1952) was a British

Inglis was involved with the Cambridge University Officer Training Corps (CUOTC), being commissioned a second lieutenant on 24 May 1909. He served with the CUOTC's engineering detachment and noticed that when the unit was deployed on field days with the rest of the force it often had little to do. To remedy this, Inglis designed a reusable steel bridge, with the intention that it could be erected and dismantled by the unit in a single afternoon. An army general who was inspecting the unit noticed his design and offered advice: "If you're making anything for the army, keep it simple – no complicated gadgets". Upon the outbreak of the

Inglis was involved with the Cambridge University Officer Training Corps (CUOTC), being commissioned a second lieutenant on 24 May 1909. He served with the CUOTC's engineering detachment and noticed that when the unit was deployed on field days with the rest of the force it often had little to do. To remedy this, Inglis designed a reusable steel bridge, with the intention that it could be erected and dismantled by the unit in a single afternoon. An army general who was inspecting the unit noticed his design and offered advice: "If you're making anything for the army, keep it simple – no complicated gadgets". Upon the outbreak of the  The Inglis Bridge was designed so that all of its components could be moved by manpower alone; moreover, it could be erected with few tools in a short span of time – a

The Inglis Bridge was designed so that all of its components could be moved by manpower alone; moreover, it could be erected with few tools in a short span of time – a

Inglis returned to Cambridge in 1918 and was appointed as the professor of Mechanism and Applied Mechanics (renamed Mechanical Sciences in 1934). On 25 March 1919, he was selected to head the

Inglis returned to Cambridge in 1918 and was appointed as the professor of Mechanism and Applied Mechanics (renamed Mechanical Sciences in 1934). On 25 March 1919, he was selected to head the  Inglis had close contacts with industry and was able to establish a professorship in

Inglis had close contacts with industry and was able to establish a professorship in  In 1930 Inglis was appointed to the board of inquiry looking into the crash of the airship R101, and in the same year was made a

In 1930 Inglis was appointed to the board of inquiry looking into the crash of the airship R101, and in the same year was made a

Inglis was due to retire from the university in 1940, but was persuaded to remain for another three years so that John Baker could be appointed in his stead. Interest in Inglis' army bridge was rekindled in the Second World War and the Mark III design introduced in 1940. Inglis applied for a United States patent for the particular type of triangular trusses used in his bridge in 1940; which was approved and granted in 1943. Testing of a prototype of the Mark III revealed a weakness in the top chord of the truss and the subsequent redesign complicated the production process. Whilst the bridge was produced in limited quantities from 1940 it was largely replaced by the

Inglis was due to retire from the university in 1940, but was persuaded to remain for another three years so that John Baker could be appointed in his stead. Interest in Inglis' army bridge was rekindled in the Second World War and the Mark III design introduced in 1940. Inglis applied for a United States patent for the particular type of triangular trusses used in his bridge in 1940; which was approved and granted in 1943. Testing of a prototype of the Mark III revealed a weakness in the top chord of the truss and the subsequent redesign complicated the production process. Whilst the bridge was produced in limited quantities from 1940 it was largely replaced by the

civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing i ...

. The son of a medical doctor, he was educated at Cheltenham College

Cheltenham College is a public school ( fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The school opened in 1841 as a Church of England foundation and is known for its outstanding linguis ...

and won a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge

King's College, formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, is a List of colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college lies beside the River Cam and faces ...

, where he would later forge a career as an academic. Inglis spent a two-year period with the engineering firm run by John Wolfe-Barry before he returned to King's College as a lecturer. Working with Professors James Alfred Ewing

Sir James Alfred Ewing MInstitCE (27 March 1855 − 7 January 1935) was a Scottish physicist and engineer, best known for his work on the magnetic properties of metals and, in particular, for his discovery of, and coinage of the word, ''hy ...

and Bertram Hopkinson, he made several important studies into the effects of vibration on structures and defects on the strength of plate steel.

Inglis served in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

during the First World War and invented the Inglis Bridge, a reusable steel bridging system – the precursor to the more famous Bailey bridge

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, Prefabrication, pre-fabricated, Truss Bridge, truss bridge. It was developed in 1940–1941 by the British Empire in World War II, British for military use during the World War II, Second World War and saw ...

of the Second World War. In 1916 he was placed in charge of bridge design and supply at the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

and, with Giffard Le Quesne Martel

Lieutenant-General Sir Giffard Le Quesne Martel (10 October 1889 – 3 September 1958) was a British Army officer who served in both the First and Second World Wars. Familiarly known as "Q Martel" or just "Q", he was a pioneering British mili ...

, pioneered the use of temporary bridges with tanks. Inglis retired from military service in 1919 and was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

. He returned to Cambridge University after the war as a professor and head of the Engineering Department

An engine department or engineering department is an organizational unit aboard a ship that is responsible for the operation, maintenance, and repair of the propulsion systems and the support systems for crew, passengers, and cargo.

These includ ...

. Under his leadership, the department became the largest in the university and one of the best regarded engineering schools in the world. Inglis retired from the department in 1943.

Inglis was associated with the Institution of Naval Architects, Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

, Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 110,000 member ...

, Institution of Structural Engineers

The Institution of Structural Engineers is a British professional body for structural engineers.

In 2021, it had 29,900 members operating in 112 countries. It provides professional accreditation and publishes a magazine, '' The Structural Eng ...

, Institution of Waterworks Engineers and British Waterworks Association; he sat on several of their councils and was elected the Institution of Civil Engineers' president for the 1941–42 session. He was also a fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

. Inglis sat on the board of inquiry investigating the loss of the airship R101 and was chair of a Ministry of War Transport

The Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) was a department of the British Government formed early in the Second World War to control transportation policy and resources. It was formed by merging the Ministry of Shipping and the Ministry of Transpor ...

railway modernisation committee in 1946. Knighted in 1945, he spent his later years developing his theories on the education of engineers and wrote a textbook on applied mechanics. He has been described as the greatest teacher of engineering of his time and has a building named in his honour at Cambridge University.

Early life and career

Charles Inglis was the second son of Dr. Alexander Inglis (ageneral practitioner

A general practitioner (GP) is a doctor who is a Consultant (medicine), consultant in general practice.

GPs have distinct expertise and experience in providing whole person medical care, whilst managing the complexity, uncertainty and risk ass ...

in Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engl ...

) and his first wife, Florence, the daughter of newspaper proprietor John Frederick Feeney. His elder brother was the historian John Alexander Inglis

John Alexander Inglis of Auchendinny and Redhall FRSE KC LLB (1873–1941) was a Scottish landowner, advocate and historian. He specialised in family histories of Scotland’s gentry.

Life

He was born at Montpelier Lawn in Cheltenham in En ...

FRSE

Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) is an award granted to individuals that the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy of science and Literature, letters, judged to be "eminently distinguished in their subject". ...

Their father, Alexander Inglis was born in Scotland to a respectable family – his grandfather, John Inglis, was an Admiral in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and had captained HMS ''Belliqueux'' at the Battle of Camperdown

The Battle of Camperdown (Dutch language, Dutch: ''Zeeslag bij Kamperduin'') was fought on 11 October 1797 between the Royal Navy's Commander-in-Chief, North Sea, North Sea Fleet under Admiral Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Duncan, Adam Duncan and a ...

in 1797.

Charles Inglis was born on 31 July 1875. He was not expected to survive and was hurriedly baptised in his father's drawing room; his mother died from complications eleven days later. His family moved to Cheltenham and Inglis was schooled at Cheltenham College

Cheltenham College is a public school ( fee-charging boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18) in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. The school opened in 1841 as a Church of England foundation and is known for its outstanding linguis ...

from 1889 to 1894. In his final year, he was elected head boy

The two Senior Prefects, individually called Head Boy (for the male), and Head Girl (for the female) are students who carry leadership roles and are responsible for representing the school's entire student body. Although mostly out of use, in some ...

and received a scholarship to study the Mathematics Tripos

The Mathematical Tripos is the mathematics course that is taught in the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge.

Origin

In its classical nineteenth-century form, the tripos was a distinctive written examination of undergraduate s ...

at King's College, Cambridge

King's College, formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, is a List of colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college lies beside the River Cam and faces ...

. Inglis was 22nd wrangler when he received his Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

degree in 1897; he remained for a fourth year, achieving first class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied, sometimes with significant var ...

in Mechanical Sciences. Inglis was a keen sportsman and enjoyed long-distance running, walking, mountaineering and sailing. At Cambridge, he nearly achieved a blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB color model, RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB color model, RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between Violet (color), violet and cyan on the optical spe ...

for long-distance running but was forced to withdraw from a significant race because of a pulled muscle. He was also a follower of the Cambridge University Rugby Union team, watching their matches at Grange Road.

After graduation, Inglis began work as an apprentice for the civil engineering firm of John Wolfe-Barry & Partners. He worked as a draughtsman in the drawing office for several months before being placed with Alexander Gibb, who was acting as resident engineer on an extension to the Metropolitan District Railway

The Metropolitan District Railway, also known as the District Railway, was a passenger railway that served London, England, from 1868 to 1933. Established in 1864 to complete an " inner circle" of lines connecting railway termini in London, the ...

between Whitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

and Bow. Inglis was responsible for the design and supervision of all thirteen bridges on the route. It was during this time that he began his lifelong study of vibration and its effects on materials, particularly bridges.

Early academic career

In 1901 Inglis was made afellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of King's College after writing a thesis entitled ''The Balancing of Engines'', the first general treatment of the subject – which was becoming increasingly important due to the growing speeds of locomotives. In the same year, he received his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

degree and was accepted as an Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

(ICE) associate member after winning the institution's Miller Prize for his student paper on ''The Geometrical Methods in Investigating Mechanical Problems''. Inglis left his employment with Wolfe-Barry, having completed two years of his five-year apprenticeship, to return to King's College and become an assistant to James Alfred Ewing

Sir James Alfred Ewing MInstitCE (27 March 1855 − 7 January 1935) was a Scottish physicist and engineer, best known for his work on the magnetic properties of metals and, in particular, for his discovery of, and coinage of the word, ''hy ...

, professor of mechanism and applied mechanics. Inglis maintained his interest in engine balancing and filed a US patent on 16 April 1902 for an improved engine with the cylinders

A cylinder () has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infinite ...

mounted end to end to balance out the forces acting between them.

Professor Ewing left the university in 1903 to become the first Director of Naval Education at the Admiralty but Inglis remained; he was appointed a university demonstrator in mechanism

Mechanism may refer to:

*Mechanism (economics), a set of rules for a game designed to achieve a certain outcome

**Mechanism design, the study of such mechanisms

*Mechanism (engineering), rigid bodies connected by joints in order to accomplish a ...

by Professor Bertram Hopkinson, Ewing's successor, and worked with him to study the effects of vibration. Inglis was promoted to lecturer of mechanical engineering in 1908. Hopkinson recognised Inglis' academic abilities and assigned him the heaviest teaching load of all the staff, covering statics, dynamics, structural engineering theory, materials engineering, drawing, engine balance and the design of steel girders and reinforced concrete. Inglis later recalled that if he wished to learn more on a subject then he volunteered to teach a course on it. From 1911 Inglis became involved in hydraulic engineering and served on the board of the Cambridge University and Town Waterworks Company, serving as deputy chairman from 1924 to 1928 and chairman from 1928 to 1952.

Inglis conducted research into the problem of fracture in the metal plates of ships' hulls and noticed that the rivet

A rivet is a permanent mechanical fastener. Before being installed, a rivet consists of a smooth cylinder (geometry), cylindrical shaft with a head on one end. The end opposite the head is called the ''tail''. On installation, the deformed e ...

holes along the path of a crack were often deformed into an elliptical shape. This phenomenon led him to investigate the magnification of stress caused at the edges of an elliptical defect; in 1913 he published a paper of his theories that has been described as his most important contribution to engineering and the first serious modern work on the fracturing of materials. Alan Arnold Griffith

Alan Arnold Griffith (13 June 1893 – 13 October 1963) was an English engineer and the son of Victorian science fiction writer George Griffith. Among many other contributions, he is best known for his work on stress and fracture in metals that ...

later drew on Inglis' paper for his work on the apparent discrepancy between calculated and actual strengths of materials. Inglis's 1913 paper has been cited by around 1,200 subsequent works.

Inglis had married Eleanor Moffat, daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Moffat of the South Wales Borderers

The South Wales Borderers was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence for 280 years.

It came into existence in England in 1689, as Sir Edward Dering's Regiment of Foot, and afterwards had a variety of names and headquarters. In ...

, in 1901, having met on holiday in Switzerland. They lived at Maitland House, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, until 1904, when Inglis built a house he named Balls Grove at nearby Grantchester

Grantchester () is a village and civil parish on the River Cam or Granta (river), Granta in South Cambridgeshire, England. It lies about south of Cambridge.

Name

The village of Grantchester is listed in the 1086 Domesday Book as ''Granteset ...

, where his two daughters were born and the family resided until 1925. They later moved to 10 Latham Road, which Inglis renamed Niddrys after the first known address of his ancestors in Edinburgh.

Military service

Inglis was involved with the Cambridge University Officer Training Corps (CUOTC), being commissioned a second lieutenant on 24 May 1909. He served with the CUOTC's engineering detachment and noticed that when the unit was deployed on field days with the rest of the force it often had little to do. To remedy this, Inglis designed a reusable steel bridge, with the intention that it could be erected and dismantled by the unit in a single afternoon. An army general who was inspecting the unit noticed his design and offered advice: "If you're making anything for the army, keep it simple – no complicated gadgets". Upon the outbreak of the

Inglis was involved with the Cambridge University Officer Training Corps (CUOTC), being commissioned a second lieutenant on 24 May 1909. He served with the CUOTC's engineering detachment and noticed that when the unit was deployed on field days with the rest of the force it often had little to do. To remedy this, Inglis designed a reusable steel bridge, with the intention that it could be erected and dismantled by the unit in a single afternoon. An army general who was inspecting the unit noticed his design and offered advice: "If you're making anything for the army, keep it simple – no complicated gadgets". Upon the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914, Inglis volunteered for active service in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

and was officially listed as an Assistant Instructor in the School of Military Engineering, with the temporary rank of lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

. The army expressed interest in Inglis' bridge design; it was approved for use by a panel of army officers that included the general who had first commented on the design, to whom Inglis said "I hope, Sir, you will find I have profited by your advice". The design remained in service with the British Army until the higher-capacity Bailey bridge

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, Prefabrication, pre-fabricated, Truss Bridge, truss bridge. It was developed in 1940–1941 by the British Empire in World War II, British for military use during the World War II, Second World War and saw ...

was introduced during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

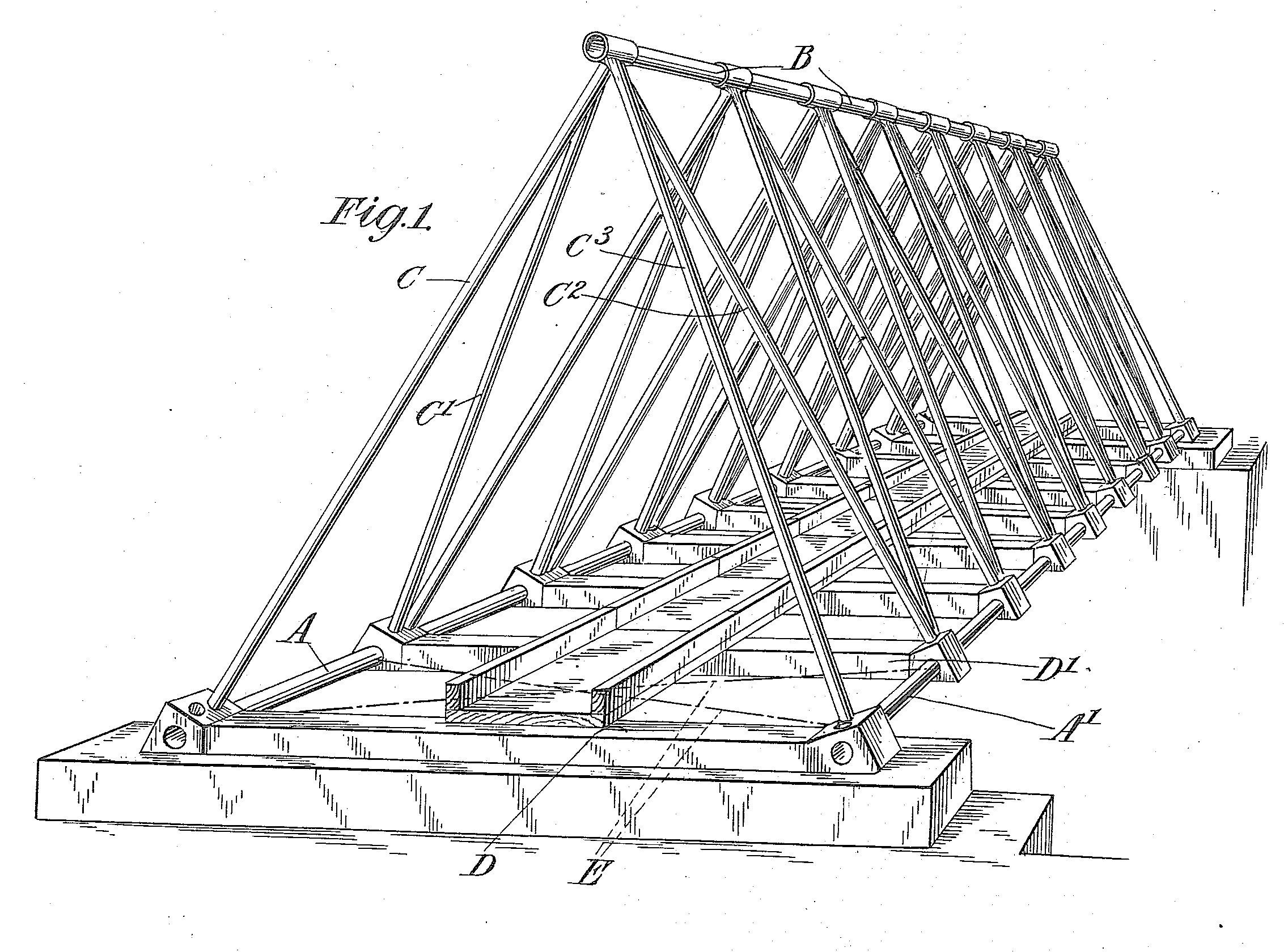

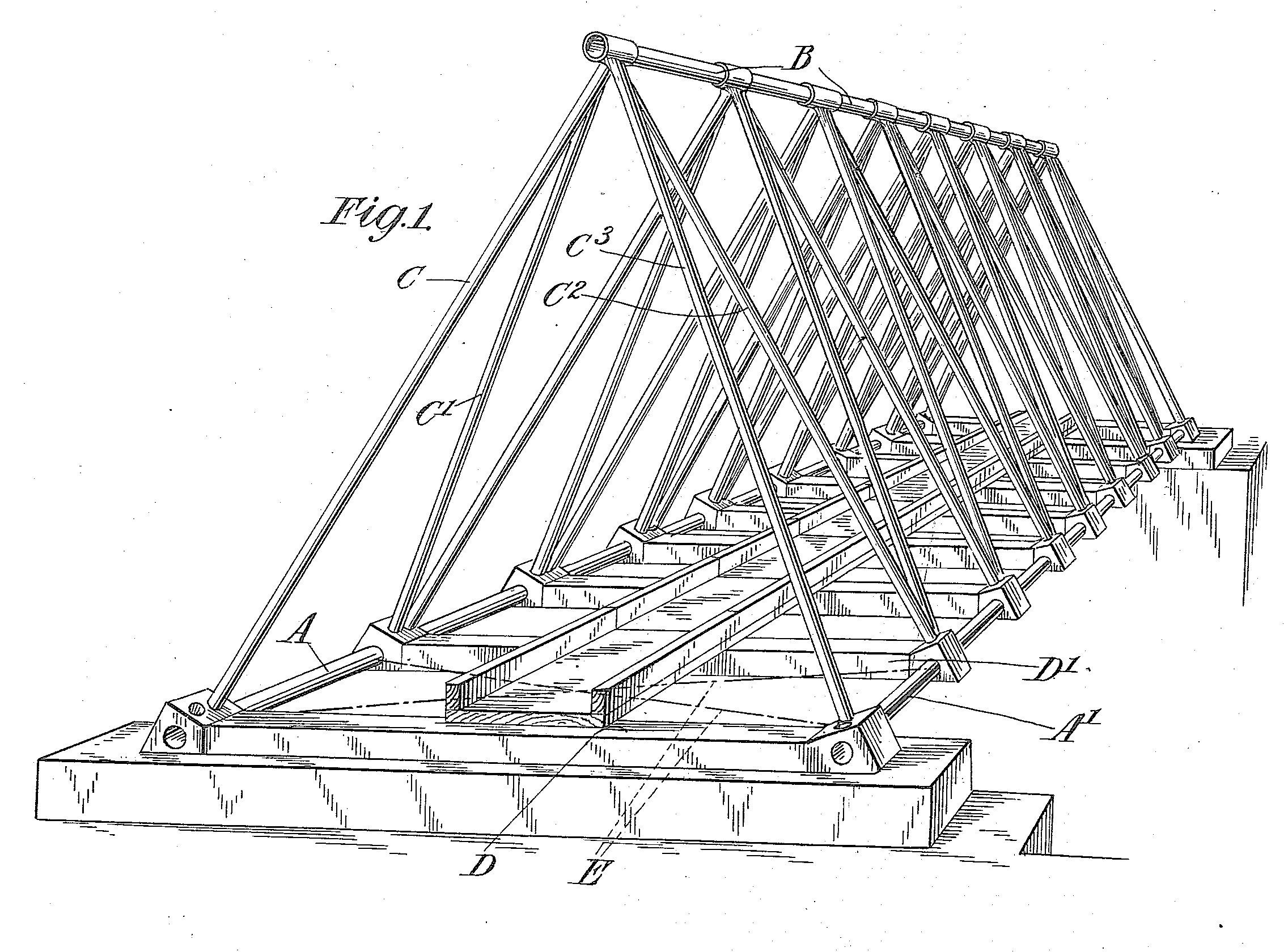

The Inglis Bridge was designed so that all of its components could be moved by manpower alone; moreover, it could be erected with few tools in a short span of time – a

The Inglis Bridge was designed so that all of its components could be moved by manpower alone; moreover, it could be erected with few tools in a short span of time – a troop

A troop is a military sub-subunit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a squadron. In many armies a troop is the equivalent element to the infantry section or platoon. Exceptions are the US Cavalry and the King's Troo ...

of 40 sappers could erect a bridge in 12 hours. The design was composed of a series of Warren truss

In structural engineering, a Warren truss or equilateral truss is a type of truss employing a weight-saving design based upon Triangle, equilateral triangles. It is named after the British engineer James Warren (engineer), James Warren, who pat ...

bays made from tubular steel sections, to a maximum span of six bays (). The design went through three revisions, with the Mark II replacing the original design's variable-length tubes with identical-length ones and, during the Second World War, the Mark III using higher strength steel but smaller tube diameters, increasing the carrying capacity to . In addition to his bridge design, during the war's course he developed the similar Inglis Tubular Observation Tower. Inglis received a US Patent for his bridge on 25 April 1916 and for the type of joints used in it on 26 June 1917.

In 1916, Inglis was placed in charge of bridge design and supply at the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

in which role he was a proponent for the increased use of girder bridge

A girder bridge is a bridge that uses girders as the means of supporting its deck. The two most common types of modern steel girder bridges are plate and box.

The term "girder" is often used interchangeably with "beam" in reference to bridge d ...

s in military applications. It was Inglis that first proved to the army that the heavy components essential to girder bridges did not prevent their rapid assembly in field conditions. This led to the greater use of such bridges, particularly the Inglis Bridge, for tanks later in the war. He received promotion to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on the General List of Officers on 6 May 1916 and became a staff captain attached to the War Office on 26 June 1917. He was promoted to the brevet rank

In military terminology, a brevet ( or ) is a warrant which gives commissioned officers a higher military rank as a reward without necessarily conferring the authority and privileges granted by that rank. The promotion would be noted in the of ...

of major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

as part of the King's Birthday Honours

The Birthday Honours, in some Commonwealth realms, mark the reigning monarch's official birthday in each realm by granting various individuals appointment into national or dynastic orders or the award of decorations and medals. The honours are ...

on 3 June 1918 and later that year worked with Giffard Le Quesne Martel

Lieutenant-General Sir Giffard Le Quesne Martel (10 October 1889 – 3 September 1958) was a British Army officer who served in both the First and Second World Wars. Familiarly known as "Q Martel" or just "Q", he was a pioneering British mili ...

to develop some of the earliest bridgelaying tanks. Inglis retired from the army on 9 March 1919, having been rewarded for his military service with an appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

.

Return to King's College

Inglis returned to Cambridge in 1918 and was appointed as the professor of Mechanism and Applied Mechanics (renamed Mechanical Sciences in 1934). On 25 March 1919, he was selected to head the

Inglis returned to Cambridge in 1918 and was appointed as the professor of Mechanism and Applied Mechanics (renamed Mechanical Sciences in 1934). On 25 March 1919, he was selected to head the Cambridge University Engineering Department

The University of Cambridge's Department of Engineering is the largest department at the university. The main site is situated at Trumpington Street, to the south of the city centre of Cambridge. The department is currently headed by Professor ...

as the successor of Hopkinson, who had died in an air crash the previous year. Though he made no radical changes, such as had occurred under his predecessors, under Inglis' supervision the department became the largest in the university and one of the best engineering schools in the world. He was responsible for expanding the department to meet the increased post-war demand for engineers and for the move from its traditional home at Free School Lane

Free School Lane is a historic street in central Cambridge, England which includes important buildings of University of Cambridge. It is the location of the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, the Department of History and Philosophy of ...

. Inglis acquired the Scroope House on Trumpington Street for the department and constructed a laboratory on the site by 1923, followed in 1931 by a structure containing lecture theatres and a drawing office.

At Cambridge Inglis' students included Sir Frank Whittle

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, (1 June 1907 – 8 August 1996) was an English engineer, inventor and Royal Air Force (RAF) air officer. He is credited with co-creating the turbojet engine. A patent was submitted by Maxime Guillaume in 1921 fo ...

(developer of the jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine, discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition may include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

), James N. Goodier (mechanical engineer and academic), Sir Morien Morgan (called the "Father of Concorde

Concorde () is a retired Anglo-French supersonic airliner jointly developed and manufactured by Sud Aviation and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Studies started in 1954, and France and the United Kingdom signed a treaty establishin ...

") and Beryl Platt, Baroness Platt (Conservative peer). He was also in contact with Russian railway engineer Yury Lomonosov and lectured to biochemist Albert Chibnall. Despite mentoring some of the best engineers of their generation Inglis was realistic about the actual intentions of many of his students at the time. He once told a new intake class: "Your fathers, gentlemen, have sent you to Cambridge to be educated, not to become engineers. They think, however, that reading engineering is a very good way of becoming educated. In 10 years' time, however, 90% of you will have become managers, whether of design, manufacturing, sales, research or even accounts departments in industry. The remaining 10% of you will have become successful lawyers, novelists, and things of that sort". Undeterred, Inglis sought to give his students the broadest possible engineering education, covering all fields to prevent them becoming "cramped by premature specialisation".

aeronautical engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is s ...

and links with a nearby Air Ministry experimental flight station. He was also successful in arranging with the War Office for Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

officers to study the Engineering Tripos at the university. The university drew praise for the quality of its teaching during Inglis' tenure, though his department has been criticised for its "comparative neglect of original research". From 1923, he was involved with the analysis of vibration and its effects on railway bridges, including a period spent working with Christopher Hinton during the latter's final year as a student at Cambridge. Inglis was appointed to a sub-committee of the British government's Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Bridge Stress Committee by Ewing, who was chairman, and became responsible for almost all of the mathematics of the investigation. Inglis derived a theory that allowed for the accurate assessment of the vibrations caused by hammer blow

In rail terminology, hammer blow or dynamic augment is a vertical force which alternately adds to and subtracts from the locomotive's weight on a wheel. It is transferred to the track by the driving wheels of many steam locomotives. It is an out-o ...

force imparted to the bridge by locomotives, and the committee's 1928 report included recommendations that the hammer blow force be included in bridge design calculations in the future. During the course of this work Inglis was able to show that the increased oscillation of bridges at train speeds beyond those that corresponded with the natural frequency

Natural frequency, measured in terms of '' eigenfrequency'', is the rate at which an oscillatory system tends to oscillate in the absence of disturbance. A foundational example pertains to simple harmonic oscillators, such as an idealized spring ...

of the bridge was due to the influence of the locomotive's suspension – the first time that this phenomenon had been explained. Inglis' work on bridge vibration has been described as his most important post-war research. He followed up the work by using a harmonic series and Macaulay's method to approximate the vibration of beams of non-uniform mass distribution or bending modulus. This work is related to the later method used by Myklestad and Prohl in the field of rotordynamics

Rotordynamics (or rotor dynamics) is a specialized branch of applied mechanics concerned with the behavior and diagnosis of rotating structures. It is commonly used to analyze the behavior of structures ranging from jet engines and steam turbin ...

.

Inglis was elected an Institution of Civil Engineers member in 1923 and became a member of its council in 1928. He was very active professionally and also served on the councils of the Institution of Naval Architects, Institution of Structural Engineers

The Institution of Structural Engineers is a British professional body for structural engineers.

In 2021, it had 29,900 members operating in 112 countries. It provides professional accreditation and publishes a magazine, '' The Structural Eng ...

and the Institution of Waterworks Engineers; he was an Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 110,000 member ...

honorary member. Inglis was also a prolific writer, publishing 25 books and academic papers on a wide range of engineering topics. He received the ICE's Telford Medal in 1924 for a paper entitled ''The Theory of Transverse Oscillations in Girders and its Relation to Live Load and Impact Allowance''. In 1926, he was appointed to a Royal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

considering cross-river traffic in London with particular reference to the Waterloo and St Paul's

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

bridges. Inglis founded the Cambridge Engineers' Association to promote social activities at the University, and saw Sir Charles Parsons

Sir Charles Algernon Parsons (13 June 1854 – 11 February 1931) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish mechanical engineer and inventor who designed the modern steam turbine in 1884. His invention revolutionised marine propulsion, and he was al ...

appointed as its first president in 1929. In the same year, he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

by the University of Edinburgh.

In 1930 Inglis was appointed to the board of inquiry looking into the crash of the airship R101, and in the same year was made a

In 1930 Inglis was appointed to the board of inquiry looking into the crash of the airship R101, and in the same year was made a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

. He was a member of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway

The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMSIt has been argued that the initials LMSR should be used to be consistent with London and North Eastern Railway, LNER, Great Western Railway, GWR and Southern Railway (UK), SR. The London, Midland an ...

's Advisory Committee on Scientific Research from 1931 to 1947 and conducted numerous experiments on their behalf in the laboratories at Cambridge. He was able to prove the factors behind hunting oscillation

Hunting oscillation is a self-oscillation, usually unwanted, about an Mechanical equilibrium, equilibrium. The expression came into use in the 19th century and describes how a system "hunts" for equilibrium. The expression is used to describe phe ...

, a violent oscillation of railway carriages, and developed testing equipment to approximate the wear of rail track and wheels in the field.

Inglis published the book ''A Mathematical Treatise on Vibrations in Railway Bridges'' in 1934, which was described by a reviewer as "a valuable asset for both the mathematician and engineer", and also submitted several papers on the matter to the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE). Inglis delivered the Trevithick Memorial Lecture for the ICE in 1933, and was elected British Waterworks Association president in 1935. At around this time, he was appointed to the governing council of Cheltenham College, of which he remained a member for the rest of his life. Inglis was the president of the 1934 International Congress on Theoretical and Applied Mechanics held at Cambridge, one of the series of Congresses that gave rise to the IUTAM. He was a proposer for the Royal Society fellowship of Andrew Robertson, the mechanical engineer, in 1936.

Second World War and after

Inglis was due to retire from the university in 1940, but was persuaded to remain for another three years so that John Baker could be appointed in his stead. Interest in Inglis' army bridge was rekindled in the Second World War and the Mark III design introduced in 1940. Inglis applied for a United States patent for the particular type of triangular trusses used in his bridge in 1940; which was approved and granted in 1943. Testing of a prototype of the Mark III revealed a weakness in the top chord of the truss and the subsequent redesign complicated the production process. Whilst the bridge was produced in limited quantities from 1940 it was largely replaced by the

Inglis was due to retire from the university in 1940, but was persuaded to remain for another three years so that John Baker could be appointed in his stead. Interest in Inglis' army bridge was rekindled in the Second World War and the Mark III design introduced in 1940. Inglis applied for a United States patent for the particular type of triangular trusses used in his bridge in 1940; which was approved and granted in 1943. Testing of a prototype of the Mark III revealed a weakness in the top chord of the truss and the subsequent redesign complicated the production process. Whilst the bridge was produced in limited quantities from 1940 it was largely replaced by the Bailey bridge

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, Prefabrication, pre-fabricated, Truss Bridge, truss bridge. It was developed in 1940–1941 by the British Empire in World War II, British for military use during the World War II, Second World War and saw ...

, introduced in 1941, a fact that disappointed Inglis. The Inglis design remained in service for some time owing to a lack of resources for production of the Bailey bridge and saw service in rear areas and with the 1st Canadian Infantry Division

The 1st Canadian Division (French: ) is a joint operational command and control formation based at CFB Kingston, and falls under Canadian Joint Operations Command. It is a high-readiness unit, able to move on very short notice, and is staffed a ...

.

Inglis was elected as ICE president for the 1941–42 session, having been vice-president in 1938, and gave an inaugural address on the education of engineers that was judged to be one of the best ever given. In his address, he stated that "the soul and spirit of education is that habit of mind which remains when a student has completely forgotten everything he has ever been taught", a quote which has since been used by several organisations to describe the importance of an engineering education. He delivered the Thomas Hawksley

Thomas Hawksley ( – ) was an English civil engineer of the 19th century, particularly associated with early water supply and coal gas engineering projects. Hawksley was, with John Frederick Bateman, the leading British water engineer of the n ...

Lecture on "Gyroscopic Principles and Applications" for the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in 1943 and the fiftieth ICE James Forrest lecture on "Mechanical Vibrations, their Cause and Prevention" in 1944, being awarded the ICE's Charles Parsons medal the same year. He gave the Parsons Memorial Lecture to the North-East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in 1945 in which he presented his Basic Function Method, an alternative to the use of Fourier series

A Fourier series () is an Series expansion, expansion of a periodic function into a sum of trigonometric functions. The Fourier series is an example of a trigonometric series. By expressing a function as a sum of sines and cosines, many problems ...

for the analysis of vibrations in beams.

After his retirement as department head Inglis served as Vice-Provost of King's College from 1943 to 1947. He received a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in the 1945 King's Birthday Honours, and in 1946 was appointed as chair of the committee charged with advising the Minister of War Transport

The Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) was a department of the British Government formed early in the Second World War to control transportation policy and resources. It was formed by merging the Ministry of Shipping and the Ministry of Transport ...

on railway modernisation. Inglis continued to develop his theories on teaching engineering and wrote in the ''Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers'' in 1947 on the teaching of engineering mathematics: "Mathematics equired by engineersthough it must be sound and incisive as far as goes, need not be of that artistic and exalted quality which calls for the mentality of the real mathematician. It can be termed mathematics of the tin-opening variety, and in contrast to real mathematicians, engineers are more interested in the contents of the tin than in the elegance of the tin-opener employed". He published the textbook ''Applied Mechanics for Engineers'' in 1951, following which he spent three months as a visiting professor

In academia, a visiting scholar, visiting scientist, visiting researcher, visiting fellow, visiting lecturer, or visiting professor is a scholar from an institution who visits a host university to teach, lecture, or perform research on a topic fo ...

at the University of the Witwatersrand

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), commonly known as Wits University or Wits, is a multi-campus Public university, public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg, South Africa. The universit ...

in South Africa. His wife, Lady Eleanor Inglis, died on 1 April 1952, and Charles died eighteen days later at Southwold

Southwold is a seaside town and civil parish on the North Sea, in the East Suffolk District, East Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England. It lies at the mouth of the River Blyth, Suffolk, River Blyth in the Suffolk Coast and Heaths ...

, Suffolk. The Cambridge University Engineering Department's Inglis Building is named in his honour. Inglis has been described as the greatest teacher of engineering of his time.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Venn; Venn (1922–1958). * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Inglis, Charles 1875 births 1952 deaths British Army personnel of World War I Military personnel from Worcester, England Royal Engineers officers Alumni of King's College, Cambridge British civil engineers Fellows of King's College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society People educated at Cheltenham College Engineers from Worcester, England Presidents of the Institution of Civil Engineers People from Cambridge People from Grantchester Professors of engineering (Cambridge, 1875)