Charles Greely Abbot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

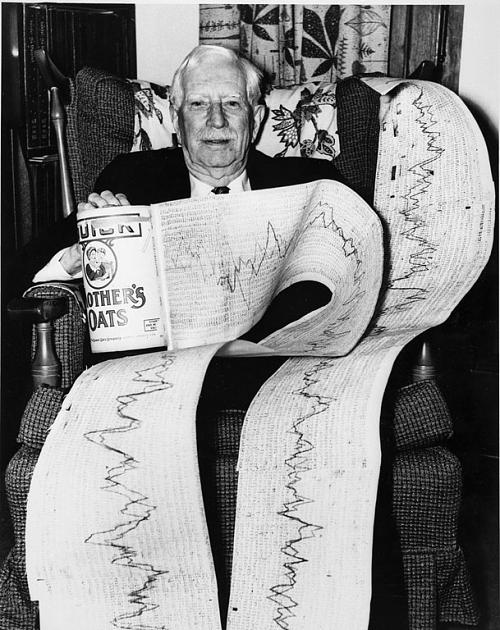

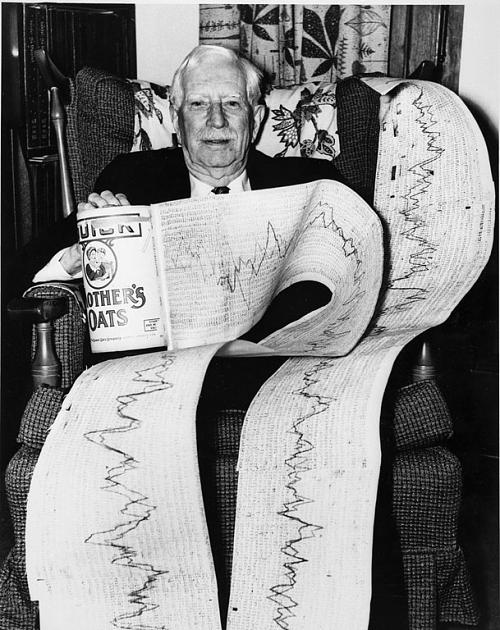

Charles Greeley Abbot (May 31, 1872 – December 17, 1973) was an American astrophysicist and the fifth secretary of the

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in

While at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), Abbot would work under Samuel P. Langley. Langley would go on to change his focus from

While at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), Abbot would work under Samuel P. Langley. Langley would go on to change his focus from

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the

Abbot began his

Abbot began his

Oral history interviews with Charles G. Abbot, 1973

from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Abbot, Charles Greeley 1872 births 1973 deaths 20th-century American astronomers American astrophysicists American centenarians Men centenarians MIT Department of Physics alumni People from Anne Arundel County, Maryland People from Wilton, New Hampshire Phillips Academy alumni Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution Solar energy Scientists from New Hampshire

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

, serving from 1928 until 1944. Abbot went from being director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) is a research institute of the Smithsonian Institution, concentrating on astrophysical studies including galactic and extragalactic astronomy, cosmology, solar, earth and planetary sciences, the ...

, to becoming Assistant Secretary, and then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution over the course of his career. As an astrophysicist, he researched the solar constant

The solar constant (''GSC'') is a flux density measuring mean solar electromagnetic radiation ( total solar irradiance) per unit area. It is measured on a surface perpendicular to the rays, one astronomical unit (au) from the Sun (roughly the ...

, research that led him to invent the solar cooker

A solar cooker is a device which uses the energy of direct sunlight to heat, cook or pasteurize drink and other food materials. Many solar cookers currently in use are relatively inexpensive, low-tech devices, although some are as powerful or a ...

, solar boiler

Solar water heating (SWH) is heating water by sunlight, using a solar thermal collector. A variety of configurations are available at varying cost to provide solutions in different climates and latitudes. SWHs are widely used for residential a ...

, solar still

A solar still distills water with substances dissolved in it by using the heat of the Sun to evaporate water so that it may be cooled and collected, thereby purifying it. They are used in areas where drinking water is unavailable, so that clea ...

, and other patented solar energy

Solar energy is radiant light and heat from the Sun that is harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar power to generate electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating), and solar architecture. It is an ...

inventions.

Early life and education

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in Wilton, New Hampshire

Wilton is a town in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,896 at the 2020 census. Like many small New England towns, it grew up around water-powered textile mills, but is now a rural bedroom community with some m ...

. His parents, Harris Abbot and Caroline Ann Greeley, were farmers and he was the youngest of four children. As a youth he built and invented numerous things, such as a forge to fix tools, a water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buck ...

to power a saw, and a bicycle. He dropped out of school when he was 13 to become a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters tra ...

. Two years later he went back to high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

. He attended Phillips Academy

("Not for Self") la, Finis Origine Pendet ("The End Depends Upon the Beginning") Youth From Every Quarter Knowledge and Goodness

, address = 180 Main Street

, city = Andover

, state = M ...

.

When a friend of his went to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

to take the entrance exam to get into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern t ...

, Abbot went for the chance to visit Boston. However, upon arrival, he was uncomfortable visiting Boston alone and chose to take the exam instead. He passed and his family gathered the funds to send him to MIT for one year. He started out studying chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials in ...

, but eventually moved on to physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

.

He graduated in 1894 with a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast ...

in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

. During his time in Boston, Abbot met Samuel P. Langley on the MIT campus when Langley visited seeking an assistant. In 1895, he would start working as an aid at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) is a research institute of the Smithsonian Institution, concentrating on astrophysical studies including galactic and extragalactic astronomy, cosmology, solar, earth and planetary sciences, the ...

.

Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

While at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), Abbot would work under Samuel P. Langley. Langley would go on to change his focus from

While at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), Abbot would work under Samuel P. Langley. Langley would go on to change his focus from solar radiation

Solar irradiance is the power per unit area ( surface power density) received from the Sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation in the wavelength range of the measuring instrument.

Solar irradiance is measured in watts per square metre ...

to aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identif ...

, with Abbot taking over solar radiation research. Abbot would participate in many expeditions

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

. In 1900 he, along with Langley, would travel to Wadesboro, North Carolina

Wadesboro is a town in Anson County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 5,049 at the 2020 census. The town was originally found in 1783 as New Town but changed by the North Carolina General Assembly to Wadesboro in 1787 to honor C ...

to observe a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six mo ...

, followed by another eclipse expedition to Sumatra in 1901. During his expedition experiences he would also travel to Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, religi ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

, Australia, and other countries, often in partnership with the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, ...

. Abbot would become acting director of SAO in 1906 and in 1907, Abbot became the Director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, following the death of Samuel P. Langley. While Langley was still Director, he had visited Mount Whitney

Mount Whitney ( Paiute: Tumanguya; ''Too-man-i-goo-yah'') is the highest mountain in the contiguous United States and the Sierra Nevada, with an elevation of . It is in East– Central California, on the boundary between California's Inyo and ...

, and decided it would be a great place for an observatory. Abbot secured funding for the observatory and it was built in 1909. As Director, a position he would hold until his retirement, Abbot would open the Radiation Biology Laboratory in 1929, to study radiation effects on plants, and other organisms. This helped to develop the first wave of biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. ...

researchers in the United States.

Life and work as Smithsonian Secretary

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

in 1918, upon the death of Frederick W. True

Frederick William True (July 8, 1858 – June 25, 1914) was an American biologist, the first head curator of biology (1897–1911) at the United States National Museum, now part of the Smithsonian Institution.

Biography

He was born in Middletown ...

. In his role as Assistant Secretary he would oversee the Smithsonian Institution Libraries

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Institutio ...

, the International Exchange Service

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

, and the SAO. He also co-created the ''Smithsonian Scientific Series'' books, which helped raise funds for the Smithsonian.

Ten years later, on January 10, 1928, he became the fifth Secretary of the Smithsonian after the death of Charles Doolittle Walcott

Charles Doolittle Walcott (March 31, 1850February 9, 1927) was an American paleontologist, administrator of the Smithsonian Institution from 1907 to 1927, and director of the United States Geological Survey.Wonderful Life (book) by Stephen Jay G ...

. Abbot would also maintain his position as Director of the Astrophysical Observatory. In 1927, Walcott had finalized the Smithsonian's strategic plan

Strategic planning is an organization's process of defining its strategy or direction, and making decisions on allocating its resources to attain strategic goals.

It may also extend to control mechanisms for guiding the implementation of the s ...

, which Abbot took on responsibility for upon his election as Secretary. The Smithsonian began a capital campaign

Fundraising or fund-raising is the process of seeking and gathering voluntary financial contributions by engaging individuals, businesses, charitable foundations, or governmental agencies. Although fundraising typically refers to efforts to gathe ...

in 1929, coinciding with the start of the Great Depression. During this tenure, Abbot oversaw the Smithsonian's participation in Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, in ...

projects, including the Federal Art Project

The Federal Art Project (1935–1943) was a New Deal program to fund the visual arts in the United States. Under national director Holger Cahill, it was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administr ...

. Projects included new buildings and artwork at the National Zoo, and the start of the Smithsonian's first media project, a radio show

A radio program, radio programme, or radio show is a segment of content intended for broadcast on radio. It may be a one-time production or part of a periodically recurring series. A single program in a series is called an episode.

Radio netwo ...

called ''The World is Yours''. The program would be ceased in 1942 due to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. In the 1930s an expansion was approved for the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with ...

building, which would not begin until the 1960s. The Institute for Social Anthropology

The Institute for Social Anthropology (ISA) is a research institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (AAS) in Vienna, Austria.

Tasks and Aims

The Institute for Social Anthropology is an Asia-specialized research institute at the AAS. Its lo ...

was also transferred to the Smithsonian during this time. While Secretary, Abbot would fail to acquire the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art, and its attached Sculpture Garden, is a national art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of ch ...

for the Smithsonian. Abbot's role in the United States National Museum

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

was also minimal, and was under the primary care of Assistant Secretary Alexander Wetmore

Frank Alexander Wetmore (June 18, 1886 – December 7, 1978) was an American ornithologist and avian paleontologist. He was the sixth Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

Early life and education

The son of a Country Physician, Frank Ale ...

.

He was the first Smithsonian Secretary to retire, ending his tenure on July 1, 1944. Following retirement, he was awarded Secretary Emeritus status and proceeded to continue his research work. The first Smithsonian holiday party would be held during his tenure. At the party, Abbot sang and played the cello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a Bow (music), bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), t ...

for the partygoers. While in Washington, he was a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

at the First Congregational Church. He also played tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball c ...

frequently at the former tennis courts at the Smithsonian Castle.

Later life and legacy

On May 31, 1955, the Smithsonian held abirthday party

A party is a gathering of people who have been invited by a host for the purposes of socializing, conversation, recreation, or as part of a festival or other commemoration or celebration of a special occasion. A party will often feature ...

for Abbot, marking his 83rd birthday and his 60th year of association with the Smithsonian. The event was held at the Smithsonian Castle

The Smithsonian Institution Building, located near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. behind the National Museum of African Art and the Sackler Gallery, houses the Smithsonian Institution's administrative offices and information center. Th ...

and a bronze bust of Abbot, by Alicia Neatherly Alicia may refer to:

People

* Alicia (given name), list of people with this name

* Alisha (singer) (born 1968), US pop singer

* Melinda Padovano (born 1987), a professional wrestler, known by her ring name, Alicia

Places

* Alicia, Bohol, Phi ...

, was presented, and donated to the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art, and its attached Sculpture Garden, is a national art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of ch ...

. Charles Greeley Abbot died, at age 101 in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

, on December 17, 1973. The American Solar Energy Society

The American Solar Energy Society (ASES) is an association of solar professionals and advocates in the United States. Founded in 1954, ASES is dedicated to inspiring energy innovation and speeding up the transition toward a sustainable energy eco ...

has an award named in Abbot's honor, which is awarded for contributions to solar energy

Solar energy is radiant light and heat from the Sun that is harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar power to generate electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating), and solar architecture. It is an ...

research.

The Abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. Th ...

crater on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

has been named after him.

Research work

Abbot began his

Abbot began his astrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline said, Astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the nature of the he ...

research focusing on solar radiation before proceeding to chart cyclic patterns found in solar variation

The solar cycle, also known as the solar magnetic activity cycle, sunspot cycle, or Schwabe cycle, is a nearly periodic 11-year change in the Sun's activity measured in terms of variations in the number of observed sunspots on the Sun's surfa ...

s. With this research he hoped to track solar constant

The solar constant (''GSC'') is a flux density measuring mean solar electromagnetic radiation ( total solar irradiance) per unit area. It is measured on a surface perpendicular to the rays, one astronomical unit (au) from the Sun (roughly the ...

in order to make weather pattern predictions. He believed that the sun was a variable star

A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) changes with time. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are classified as e ...

which effected the weather on Earth, which was criticized by many contemporaries. In 1953, he discovered a connection between solar variations and planetary climate. This discovery allowed general climate patterns to be predicted 50 years in advance. He did field work at the Smithsonian Institution Shelter

The Smithsonian Institution Shelter, also known as the Mount Whitney Summit Shelter and the Mount Whitney Hut, was built in 1909 on the summit plateau of Mount Whitney, in the Sierra Nevada within Sequoia National Park, in California. It is the hi ...

, which was built during his tenure as director at SAO, Lick Observatory, and Mount Wilson Observatory

The Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO) is an astronomical observatory in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The MWO is located on Mount Wilson, a peak in the San Gabriel Mountains near Pasadena, northeast of Los Angeles.

The observ ...

. At Lick, he worked with W.W. Campbell

William Wallace Campbell (April 11, 1862 – June 14, 1938) was an American astronomer, and director of Lick Observatory from 1901 to 1930. He specialized in spectroscopy. He was the tenth president of the University of California from 1923 to ...

. To fight critics, Abbot would utilize balloons with pyrheliometer

A pyrheliometer is an instrument for measurement of direct beam solar irradiance. Sunlight enters the instrument through a window and is directed onto a thermopile which converts heat to an electrical signal that can be recorded. The signal vo ...

s installed on them for measurements. He was the first scientist in America to do so, with the balloons reaching upwards of 25 kilometers. One balloon returned data that allowed Abbot to determine the solar constant at the highest point of the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

. Later in his research career, he turned his focus on solar energy

Solar energy is radiant light and heat from the Sun that is harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar power to generate electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating), and solar architecture. It is an ...

use.

An instrumentalist

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

, he invented the solar cooker

A solar cooker is a device which uses the energy of direct sunlight to heat, cook or pasteurize drink and other food materials. Many solar cookers currently in use are relatively inexpensive, low-tech devices, although some are as powerful or a ...

, which was first built at Mount Wilson Observatory, the solar boiler

Solar water heating (SWH) is heating water by sunlight, using a solar thermal collector. A variety of configurations are available at varying cost to provide solutions in different climates and latitudes. SWHs are widely used for residential a ...

, and held fifteen other patents related to solar energy

Solar energy is radiant light and heat from the Sun that is harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar power to generate electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating), and solar architecture. It is an ...

. For his research and contributions to the sciences, Abbot was awarded a Henry Draper Medal

The Henry Draper Medal is awarded every 4 years by the United States National Academy of Sciences "for investigations in astronomical physics". Named after Henry Draper, the medal is awarded with a gift of USD $15,000. The medal was established ...

in 1910 and a Rumford Medal

The Rumford Medal is an award bestowed by Britain's Royal Society every alternating year for "an outstandingly important recent discovery in the field of thermal or optical properties of matter made by a scientist working in Europe".

First awar ...

in 1916.

Further reading

;Selected publications by Charles Greeley Abbot *''The 1914 Tests of the Langley "Aerodrome"''. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1942). *''An Account of the Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institution.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1966). *''Adventures in the World of Science''. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press (1958). *"Astrophysical Contributions of the Smithsonian Institution." ''Science''. 104.2693 (1946): 116-119. *''Samuel Pierpont Langley.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1934). *''A Shelter for Observers on Mount Whitney.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1910). ;Bibliography *Davis, Margaret. "Charles Greeley Abbot." ''The George Washington University Magazine''. 2: 32.35. *DeVorkin, David H. ""Defending a Dream: Charles Greeley Abbot's Years at the Smithsonian." ''Journal for the History of Astronomy.'' 21.61 (1990): 121-136. *Hoyt, Douglas V. "The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Solar Constant Program." ''Reviews of Geophysics and Space Physics''. 17.3 (May 1979): 427-458 * Oehser, Paul H. ''Sons of Science: The Story of the Smithsonian Institution and its Leaders.'' New York: Henry Schuman (1949). * Ripley, Sidney Dillon. "The View From the Castle: Weather prediction is not enough: what's needed is an early-warning system to monitor change in the environment." ''Smithsonian''. 1.2 (May 1970): 2.See also

* List of centenarians (scientists and mathematicians)References

External links

Oral history interviews with Charles G. Abbot, 1973

from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Abbot, Charles Greeley 1872 births 1973 deaths 20th-century American astronomers American astrophysicists American centenarians Men centenarians MIT Department of Physics alumni People from Anne Arundel County, Maryland People from Wilton, New Hampshire Phillips Academy alumni Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution Solar energy Scientists from New Hampshire