Charles Greeley Abbot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

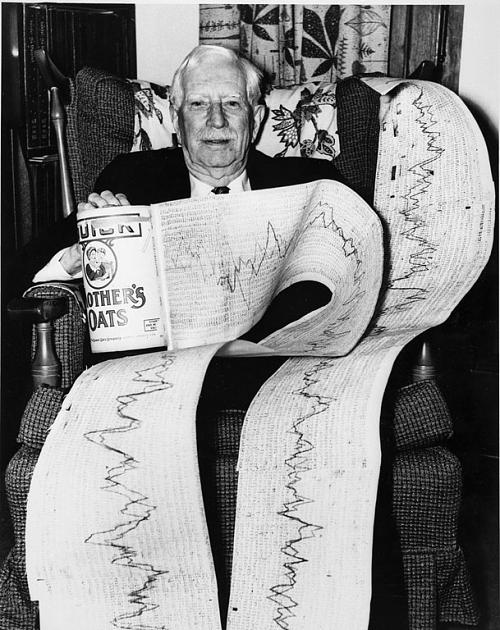

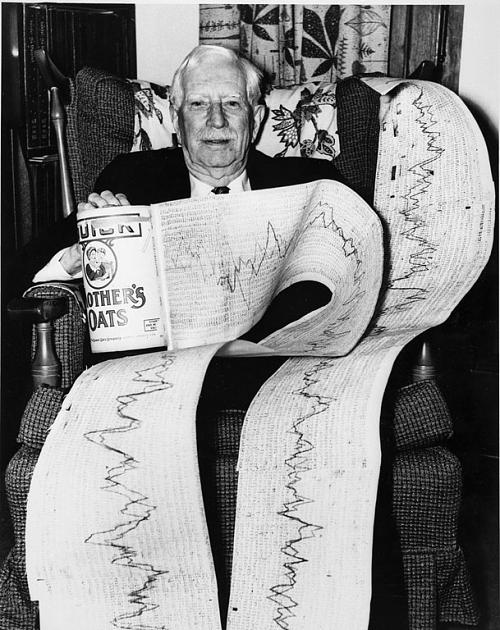

Charles Greeley Abbot (May 31, 1872 – December 17, 1973) was an American astrophysicist and the fifth secretary of the

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the

Oral history interviews with Charles G. Abbot, 1973

from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Abbot, Charles Greeley 1872 births 1973 deaths 20th-century American astronomers American astrophysicists American men centenarians Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Science alumni People from Anne Arundel County, Maryland People from Wilton, New Hampshire Phillips Academy alumni Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution Solar energy Scientists from New Hampshire Members of the American Philosophical Society Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

, serving from 1928 until 1944. Abbot went from being director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) is a research institute of the Smithsonian Institution, concentrating on Astrophysics, astrophysical studies including Galactic astronomy, galactic and extragalactic astronomy, cosmology, Sun, solar ...

, to becoming Assistant Secretary, and then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution over the course of his career. As an astrophysicist, he researched the solar constant

The solar constant (''GSC'') measures the amount of energy received by a given area one astronomical unit away from the Sun. More specifically, it is a flux density measuring mean solar electromagnetic radiation ( total solar irradiance) per un ...

, research that led him to invent the solar cooker, solar boiler, solar still

A solar still distillation, distills water with substances dissolved in it by using the Solar energy, heat of the Sun to evaporate water so that it may be cooled and collected, thereby purifying it. They are used in areas where drinking water is ...

, and other patented solar energy

Solar energy is the radiant energy from the Sun's sunlight, light and heat, which can be harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating) and solar architecture. It is a ...

inventions.

Early life and education

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in

Charles Greeley Abbot was born in Wilton, New Hampshire

Wilton is a New England town, town in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,896 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Like many small New England towns, it grew up arou ...

. His parents, Harris Abbot and Caroline Ann Greeley, were farmers and he was the youngest of four children. As a youth he built and invented numerous things, such as a forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to the ...

to fix tools, a water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous b ...

to power a saw

A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, Wire saw, wire, or Chainsaw, chain with a hard toothed edge used to cut through material. Various terms are used to describe toothed and abrasive saws.

Saws began as serrated materials, and when man ...

, and a bicycle

A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike, push-bike or cycle, is a human-powered transport, human-powered or motorized bicycle, motor-assisted, bicycle pedal, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, with two bicycle wheel, wheels attached to a ...

. He dropped out of school when he was 13 to become a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenter ...

. Two years later he went back to high school

A secondary school, high school, or senior school, is an institution that provides secondary education. Some secondary schools provide both ''lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper secondary education'' (ages 14 to 18), i.e., ...

. He attended Phillips Academy

Phillips Academy (also known as PA, Phillips Academy Andover, or simply Andover) is a Private school, private, Mixed-sex education, co-educational college-preparatory school for Boarding school, boarding and Day school, day students located in ...

.

When a friend of his went to Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

to take the entrance exam to get into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

, Abbot went for the chance to visit Boston. However, upon arrival, he was uncomfortable visiting Boston alone and chose to take the exam instead. He passed and his family gathered the funds to send him to MIT for one year. He started out studying chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of the operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials ...

, but eventually moved on to physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

.

He graduated in 1894 with a Master of Science

A Master of Science (; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree. In contrast to the Master of Arts degree, the Master of Science degree is typically granted for studies in sciences, engineering and medici ...

in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

. During his time in Boston, Abbot met Samuel P. Langley on the MIT campus when Langley visited seeking an assistant. In 1895, he would start working as an aide at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) is a research institute of the Smithsonian Institution, concentrating on Astrophysics, astrophysical studies including Galactic astronomy, galactic and extragalactic astronomy, cosmology, Sun, solar ...

.

Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

While at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), Abbot would work under Samuel P. Langley. Langley would go on to change his focus fromsolar radiation

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrared (typically p ...

to aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design process, design, and manufacturing of air flight-capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere.

While the term originally referred ...

, with Abbot taking over solar radiation research. Abbot would participate in many expeditions. In 1900 he, along with Langley, would travel to Wadesboro, North Carolina

Wadesboro is a town in and the county seat of Anson County, North Carolina, Anson County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 5,008 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The town was originally found in 1783 as New Town but ...

to observe a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs approximately every six months, during the eclipse season i ...

, followed by another eclipse expedition to Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

in 1901. During his expedition experiences he would also travel to Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, and other countries, often in partnership with the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, natural sc ...

. Abbot would become acting director of SAO in 1906 and in 1907, Abbot became the Director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, following the death of Samuel P. Langley. While Langley was still Director, he had visited Mount Whitney, and decided it would be a great place for an observatory. Abbot secured funding for the observatory and it was built in 1909. As Director, a position he would hold until his retirement, Abbot would open the Radiation Biology Laboratory in 1929, to study radiation effects on plants, and other organisms. This helped to develop the first wave of biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations ...

researchers in the United States.

Life and work as Smithsonian Secretary

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the

Abbot would become the Assistant Secretary at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1918, upon the death of Frederick W. True. In his role as Assistant Secretary he would oversee the Smithsonian Institution Libraries, the International Exchange Service, and the SAO. He also co-created the ''Smithsonian Scientific Series'' books, which helped raise funds for the Smithsonian.

Ten years later, on January 10, 1928, he became the fifth Secretary of the Smithsonian after the death of Charles Doolittle Walcott. Abbot would also maintain his position as Director of the Astrophysical Observatory. In 1927, Walcott had finalized the Smithsonian's strategic plan

Strategic planning is the activity undertaken by an organization through which it seeks to define its future direction and makes decision making, decisions such as resource allocation aimed at achieving its intended goals. "Strategy" has many def ...

, which Abbot took on responsibility for upon his election as Secretary. The Smithsonian began a capital campaign

Fundraising or fund-raising is the process of seeking and gathering voluntary financial contributions by engaging individuals, businesses, charitable foundations, or governmental agencies. Although fundraising typically refers to efforts to gathe ...

in 1929, coinciding with the start of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. During this tenure, Abbot oversaw the Smithsonian's participation in Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

projects, including the Federal Art Project

The Federal Art Project (1935–1943) was a New Deal program to fund the visual arts in the United States. Under national director Holger Cahill, it was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administratio ...

. Projects included new buildings and artwork at the National Zoo, and the start of the Smithsonian's first media project, a radio show

A radio program, radio programme, or radio show is a segment of content intended for broadcast on radio. It may be a one-time production, or part of a periodically recurring series. A single program in a series is called an episode.

Radio netw ...

called ''The World is Yours''. The program would be ceased in 1942 due to World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In the 1930s an expansion was approved for the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With 4.4 ...

building, which would not begin until the 1960s. The Institute for Social Anthropology was also transferred to the Smithsonian during this time. While Secretary, Abbot would fail to acquire the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art is an art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of charge, the museum was privately established in ...

for the Smithsonian. Abbot's role in the United States National Museum

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

was also minimal, and was under the primary care of Assistant Secretary Alexander Wetmore

Frank Alexander Wetmore (June 18, 1886 – December 7, 1978) was an American ornithologist and avian paleontologist. He was the sixth Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was also an elected member of both the American Philosophical Soc ...

.

He was the first Smithsonian Secretary to retire, ending his tenure on July 1, 1944. Following retirement, he was awarded Secretary Emeritus status and proceeded to continue his research work. The first Smithsonian holiday party would be held during his tenure. At the party, Abbot sang and played the cello

The violoncello ( , ), commonly abbreviated as cello ( ), is a middle pitched bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), tuned i ...

for the partygoers. While in Washington, he was a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Cathol ...

at the First Congregational Church. He also played tennis

Tennis is a List of racket sports, racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles (tennis), singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles (tennis), doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket st ...

frequently at the former tennis courts at the Smithsonian Castle.

Later life and legacy

During his lifetime, Abbot was elected a member of theAmerican Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

, the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

. On May 31, 1955, the Smithsonian held a birthday party

A party is a gathering of people who have been invited by a host for the purposes of socializing, conversation, recreation, or as part of a festival or other commemoration or celebration of a special occasion. A party will often feature ...

for Abbot, marking his 83rd birthday and his 60th year of association with the Smithsonian. The event was held at the Smithsonian Castle and a bronze bust of Abbot, by Alicia Neatherly, was presented, and donated to the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art is an art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of charge, the museum was privately established in ...

. Charles Greeley Abbot died, at age 101 in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, on December 17, 1973. The American Solar Energy Society has an award named in Abbot's honor, which is awarded for contributions to solar energy

Solar energy is the radiant energy from the Sun's sunlight, light and heat, which can be harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating) and solar architecture. It is a ...

research.

The Abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

crater on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

has been named after him.

Research work

Abbot began hisastrophysics

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline, James Keeler, said, astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the ...

research focusing on solar radiation before proceeding to chart cyclic patterns found in solar variations. With this research he hoped to track solar constant

The solar constant (''GSC'') measures the amount of energy received by a given area one astronomical unit away from the Sun. More specifically, it is a flux density measuring mean solar electromagnetic radiation ( total solar irradiance) per un ...

in order to make weather pattern predictions. He believed that the sun was a variable star

A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) changes systematically with time. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are ...

which effected the weather on Earth, which was criticized by many contemporaries. In 1953, he discovered a connection between solar variations and planetary climate. This discovery allowed general climate patterns to be predicted 50 years in advance. He did field work at the Smithsonian Institution Shelter, which was built during his tenure as director at SAO, Lick Observatory

The Lick Observatory is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by the University of California. It is on the summit of Mount Hamilton (California), Mount Hamilton, in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose, California, United States. The ...

, and Mount Wilson Observatory

The Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO) is an Observatory#Astronomical observatories, astronomical observatory in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The MWO is located on Mount Wilson (California), Mount Wilson, a peak in the San Gabrie ...

. At Lick, he worked with W.W. Campbell. To fight critics, Abbot would utilize balloons with pyrheliometer

A pyrheliometer is an instrument that can measure direct beam solar irradiance. Sunlight enters the instrument through a window and is directed onto a thermopile which converts heat to an electrical signal that can be recorded. The signal vol ...

s installed on them for measurements. He was the first scientist in America to do so, with the balloons reaching upwards of 25 kilometers. One balloon returned data that allowed Abbot to determine the solar constant at the highest point of the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is composed of a layer of gas mixture that surrounds the Earth's planetary surface (both lands and oceans), known collectively as air, with variable quantities of suspended aerosols and particulates (which create weathe ...

. Later in his research career, he turned his focus on solar energy

Solar energy is the radiant energy from the Sun's sunlight, light and heat, which can be harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating) and solar architecture. It is a ...

use.

An instrumentalist, he invented the solar cooker, which was first built at Mount Wilson Observatory, the solar boiler, and held fifteen other patents related to solar energy

Solar energy is the radiant energy from the Sun's sunlight, light and heat, which can be harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating) and solar architecture. It is a ...

. For his research and contributions to the sciences, Abbot was awarded a Henry Draper Medal in 1910 and a Rumford Medal in 1916.

Further reading

;Selected publications by Charles Greeley Abbot *''The 1914 Tests of the Langley "Aerodrome"''. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1942). *''An Account of the Astrophysical Observatory of the Smithsonian Institution.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1966). *''Adventures in the World of Science''. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press (1958). *"Astrophysical Contributions of the Smithsonian Institution." ''Science''. 104.2693 (1946): 116–119. *''Samuel Pierpont Langley.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1934). *''A Shelter for Observers on Mount Whitney.'' Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution (1910). ;Bibliography *Davis, Margaret. "Charles Greeley Abbot." ''The George Washington University Magazine''. 2: 32.35. *DeVorkin, David H. ""Defending a Dream: Charles Greeley Abbot's Years at the Smithsonian." ''Journal for the History of Astronomy.'' 21.61 (1990): 121–136. *Hoyt, Douglas V. "The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Solar Constant Program." ''Reviews of Geophysics and Space Physics''. 17.3 (May 1979): 427–458 * Oehser, Paul H. ''Sons of Science: The Story of the Smithsonian Institution and its Leaders.'' New York: Henry Schuman (1949). * Ripley, Sidney Dillon. "The View From the Castle: Weather prediction is not enough: what's needed is an early-warning system to monitor change in the environment." ''Smithsonian''. 1.2 (May 1970): 2.See also

*List of centenarians (scientists and mathematicians)

A list is a set of discrete items of information collected and set forth in some format for utility, entertainment, or other purposes. A list may be memorialized in any number of ways, including existing only in the mind of the list-maker, but ...

References

External links

Oral history interviews with Charles G. Abbot, 1973

from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

{{DEFAULTSORT:Abbot, Charles Greeley 1872 births 1973 deaths 20th-century American astronomers American astrophysicists American men centenarians Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Science alumni People from Anne Arundel County, Maryland People from Wilton, New Hampshire Phillips Academy alumni Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution Solar energy Scientists from New Hampshire Members of the American Philosophical Society Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences