Charles Gavan Duffy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

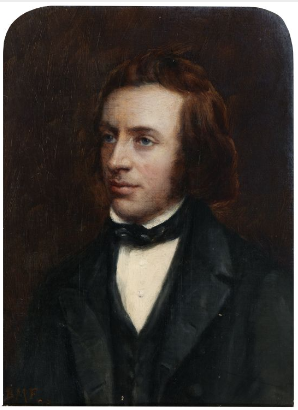

Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, KCMG, PC (12 April 1816 – 9 February 1903), was an Irish poet and journalist (editor of ''

Duffy stood on a platform of land reform. With the collapse of the

Duffy stood on a platform of land reform. With the collapse of the

When Berry became Premier in 1877 he made Duffy

When Berry became Premier in 1877 he made Duffy

The Politics of Irish Literature: from Thomas Davis to W.B. Yeats, Malcolm Brown

Allen & Unwin, 1973. * John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press. * Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son 1922. * Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher His Political and Military Career, Capt. W. F. Lyons, Burns Oates & Washbourne Limited 1869 * Young Ireland and 1848, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1949. * Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator, Dennis Gwynn, Hutchinson & Co, Ltd. * O'Connell Davis and the Colleges Bill, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1948. * Smith O'Brien And The "Secession", Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press * Meagher of The Sword, Edited By Arthur Griffith, M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd. 1916. * Young Irelander Abroad The Diary of Charles Hart, Edited by Brendan O'Cathaoir, University Press. * John Mitchel First Felon for Ireland, Edited By Brian O'Higgins, Brian O'Higgins 1947. * Rossa's Recollections 1838 to 1898, Intro by Sean O'Luing, The Lyons Press 2004. * Labour in Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1910. * The Re-Conquest of Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1915. * John Mitchel Noted Irish Lives, Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd 1934. * Thomas Davis: Essays and Poems, Centenary Memoir, M. H Gill, M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd MCMXLV. * Life of John Martin, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy & Co., Ltd 1901. * Life of John Mitchel, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy and Co., Ltd 1908. * John Mitchel, P. S. O'Hegarty, Maunsel & Company, Ltd 1917. * The Fenians in Context Irish Politics & Society 1848–82, R. V. Comerford, Wolfhound Press 1998 * William Smith O'Brien and the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848, Robert Sloan, Four Courts Press 2000 * Irish Mitchel, Seamus MacCall, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1938. * Ireland Her Own, T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd 1976. * Life and Times of Daniel O'Connell, T. C. Luby, Cameron & Ferguson. * Young Ireland, T. F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945. * Irish Rebel John Devoy and America's Fight for Irish Freedom, Terry Golway, St. Martin's Griffin 1998. * Paddy's Lament Ireland 1846–1847 Prelude to Hatred, Thomas Gallagher, Poolbeg 1994. * The Great Shame, Thomas Keneally, Anchor Books 1999. * James Fintan Lalor, Thomas, P. O'Neill, Golden Publications 2003. * Charles Gavan Duffy: Conversations With Carlyle (1892), with Introduction, Stray Thoughts on Young Ireland, by Brendan Clifford, Athol Books, Belfast, . (Pg. 32 Titled, Foster's account of Young Ireland.) * Envoi, Taking Leave of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork. * The Falcon Family, or, Young Ireland, by M. W. Savage, London, 1845.

An Gorta Mor

''Quinnipiac University''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Duffy, Charles Gavan 1816 births 1903 deaths Australian federationists Irish emigrants to colonial Australia Irish knights Irish male poets Australian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian Knights Bachelor Young Irelanders 19th-century Irish businesspeople Activists for Irish land reform Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wexford constituencies (1801–1922) Irish newspaper editors UK MPs 1852–1857 Politicians from County Monaghan Premiers of Victoria Victoria (state) state politicians Irish newspaper founders Speakers of the Victorian Legislative Assembly People educated at St Malachy's College 19th-century Irish poets 19th-century Australian journalists 19th-century Australian male writers Alumni of King's Inns Australian male journalists Members of the Victorian Legislative Assembly Presidents of the Board of Land and Works Chief secretaries of Victoria Ministers for public works (Victoria) People from Monaghan (town) Writers from County Monaghan Commissioners of crown lands and survey (Victoria) Businesspeople awarded knighthoods

The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

''), Young Ireland

Young Ireland (, ) was a political movement, political and cultural movement, cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation (Irish news ...

er and tenant-rights activist. After emigrating to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

in 1856 he entered the politics of Victoria on a platform of land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

, and in 1871–1872 served as the colony's 8th Premier.

Ireland

Early life and career

Duffy was born at No. 10 Dublin Street in Monaghan Town,County Monaghan

County Monaghan ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of Border Region, Border strategic planning area of the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, the son of a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

shopkeeper. He was educated in Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

at St Malachy's College

St Malachy's College, in Belfast, Northern Ireland, is the oldest Catholic diocesan college in Ulster. The college's alumni and students are known as Malachians.

History

The college, founded by William Crolly, Bishop William Crolly, opened on th ...

and in the collegiate department of the Royal Belfast Academical Institution

The Royal Belfast Academical Institution is an independent grammar school in Belfast, Northern Ireland. With the support of Belfast's leading reformers and democrats, it opened its doors in 1814. Until 1849, when it was superseded by what today ...

where he studied logic, rhetoric and ''belles-lettres''.

One day, when Duffy was aged 18, Charles Hamilton Teeling, a United Irish veteran of the 1798 rising, walked into his mother's house (his father had died when he was 10). Teeling was establishing a journal in Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

and asked Duffy to accompany him on a round of calls to promote it in Monaghan. Inspired by Teeling's recollections of '98, Duffy began contributing to the journal, ''The Northern Herald''.

In Belfast, Duffy went on to edit ''The Vindicator'', an O'Connellite journal launched by Thomas O'Hagan (later the first Catholic to become Lord Chancellor of Ireland

The Lord High Chancellor of Ireland, commonly known as the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, was the highest ranking judicial office in Ireland until the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. From 1721 until the end of 1800, it was also the hi ...

since 1687). At the same time, he began studying law at the King's Inns

The Honorable Society of King's Inns () is the "Inn of Court" for the Bar of Ireland. Established in 1541, King's Inns is Ireland's oldest school of law and one of Ireland's significant historical environments.

The Benchers of King's Inns aw ...

in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

.

Duffy was admitted to the Irish Bar in 1845. But before then he established himself in literary circles as the editor of ''Ballad Poetry of Ireland'' (1843), and in political circles as editor of a new Dublin weekly, ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

''.

''The Nation''

In 1842, Duffy co-founded ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'' with Thomas Osborne Davis, and John Blake Dillon. Contributors were notable for including nationally minded Protestants: in addition to Davis, Jane Wilde, Margaret Callan, John Mitchel

John Mitchel (; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist writer and journalist chiefly renowned for his indictment of British policy in Ireland during the years of the Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famin ...

, John Edward Pigot and William Smith O'Brien. All were members or supporters of Daniel O'Connell

Daniel(I) O’Connell (; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilisation of Catholic Irelan ...

's Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to ...

, dedicated to a restoration of an Irish parliament through a reversal of the 1800 Acts of Union.

When he had first followed O'Connell, Duffy concedes that he had "burned with the desire to set up again the Celtic race and the catholic church".Moody, p 38. But in ''The Nation'' (which repeatedly invoked memory of the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

) Duffy committed himself to a "nationality" that would embrace as easily "the stranger who is within our gates" as "the Irishman of a hundred generations." This expansive, ecumenical, view of the opinion-forming tasks of the paper brought him into conflict with the clericalism of the broader movement.

At issue with O'Connell

O'Connell's paper, ''The Pilot'', did not hesitate to identify religion as the "positive and unmistakable" mark of distinction between Irish and English. As leader of theCatholic Association

The Catholic Association was an Irish Roman Catholic political organization set up by Daniel O'Connell in the early nineteenth century to campaign for Catholic emancipation within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was one of ...

, O'Connell had fought to secure not only Catholic entry to Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

but also the prerogatives and independence of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. It was, he maintained, "a national Church" and should the people "rally" to him, they would "have a nation for that Church". O'Connell, at least privately, was of the view that "Protestantism would not survive the Repeal ten years". He assured Dr Paul Cullen (the future Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

and Catholic Primate of Ireland

The Primacy of Ireland belongs to the diocesan bishop of the Irish diocese with highest Order of precedence, precedence. The Archbishop of Armagh is titled Primate of All Ireland and the Archbishop of Dublin Primate of Ireland, signifying that t ...

) that once an Irish parliament had swept aside Ascendancy privilege, "the great mass of the Protestant community would with little delay melt into the overwhelming majority of the Irish nation".

In 1845, the Dublin Castle administration

Dublin Castle was the centre of the government of Ireland under English and later British rule. "Dublin Castle" is used metonymically to describe British rule in Ireland. The Castle held only the executive branch of government and the Privy Cou ...

proposed to educate Catholics and Protestants together in a non-denominational system of higher education. ''The Nation'' welcomed the proposition, but O'Connell, claiming that there had been "unanimous and unequivocal condemnation" from the bishops", opposed. Disregarding Thomas Davis's plea that "reasons for separate education are reasons for separate life", and declaring himself content to take a stand "for Old Ireland", O'Connell rejected the "godless" colleges.

For Duffy there was a further, less liberal basis, for his disaffection: O'Connell's repeated denunciations of a "vile union" in the United States "of republicanism and slavery", and his appeal to Irish Americans to join in the abolitionist struggle. Duffy believed the time was not right "for gratuitous interference in American affairs". Not least because of the desire for American support and funding, it was a common view.

Young Ireland

Following Davis's sudden death in 1845, Duffy appointedJohn Mitchel

John Mitchel (; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist writer and journalist chiefly renowned for his indictment of British policy in Ireland during the years of the Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famin ...

deputy editor. Against the background of increasingly violent peasant resistance to evictions and of the onset of famine, Mitchell brought a more militant tone. When the ''Standard'' in London observed that the new Irish railways could be used to transport troops to quickly curb agrarian unrest, Mitchel responded that the tracks could be turned into pikes and trains ambushed. O'Connell publicly distanced himself from the seditious import of the remarks—it appeared to some setting Duffy, as the publisher, up for prosecution. When the courts failed to convict, O'Connell pressed the issue, seemingly intent on effecting a break with those he referred to disdainfully as "Young Irelanders"—a reference to Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

's anti-clerical and insurrectionist Young Italy.

In 1847, the Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to ...

tabled resolutions declaring that under no circumstances was a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms. The Young Irelanders had not advocated physical force, but in response to the "Peace Resolutions" Thomas Meagher argued that if Repeal could not be carried by moral persuasion and peaceful means, a resort to arms would be a no less honourable course. O'Connell's son John forced the decision: the resolution was carried on the threat of the O'Connells themselves quitting the Association.

Duffy and the other Young Ireland dissidents associated with his paper withdrew and formed themselves as the Irish Confederation.

In the desperate circumstances of the Great Famine and in the face of martial-law measures that, following O'Connell's death, a number of Repeal Association MPs had approved in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, Duffy conceded the case for taking "the no less honourable course". With Mitchel he was arrested, leaving it to Meagher, O'Brien and Dillon to raise the standard of revolt. This was a republican tricolour with which Meagher had returned from revolutionary Paris, its colours intended to symbolise reconciliation (white) between Catholic (green) and Protestant (orange). But with the rural priesthood against them and the body of their support confined to the garrisoned towns, their efforts issued in a small demonstration that broke up after its first armed encounter, the Battle of Ballingarry. Their death sentences for treason commuted, the leaders were transported to Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

(Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

). Duffy alone escaped. Defended by Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist par ...

he was freed after his fifth trial.

The League of North and South

On his release, Duffy toured famine-stricken Ireland with the renowned Scottish essayist, historian and philosopherThomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

. Duffy had invited Carlyle, a Unionist and anti-Catholic, in the vain hope that he might help sway establishment opinion in favour of humane and practical relief. Increasingly he was convinced that agrarian reform was the nation's existential issue and one that could form the basis for a non-sectarian national movement. From his youth Duffy recalled a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

neighbour who had been a United Irishman and had laughed at the idea that the issue was kings and governments. What mattered was the land from which the people got their bread. Instead of singing ''La Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. It was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by the First French Republic against Austria, and was originally titled "".

The French Na ...

'', he said that what the men of '98 should have borrowed from the French was "their sagacious idea of bundling the landlords out of doors and putting tenants in their shoes".

In 1842, he had already allied himself with James GodkinSmith, G.B., 'Godkin, James (1806–1879)', rev. C. A. Creffield, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'' (Oxford University Press, 2004) who had abandoned a bible mission to campaign for the rights of the Catholic tenants he had been tasked with bringing into the Protestant fold. He now looked to James MacKnight (M'Knight) who, closely aided by a group of radical Presbyterian ministers, in 1847 had formed the Ulster Tenant Right Association in Derry.

In 1850, a convention called in Dublin by Duffy and MacKnight formed the Irish Tenant Right League

The Tenant Right League was a federation of local societies formed in Ireland in the wake of the Great Famine to check the power of landlords and advance the rights of tenant farmers. An initiative of northern unionists and southern nationali ...

. It was committed in its charter to MacKnight's " three F's": fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure.

Uniting activists across the sectarian and constitutional divide, in 1852, the League helped return Duffy (for New Ross

New Ross (, formerly ) is a town in southwest County Wexford, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, on the River Barrow on the border with County Kilkenny, northeast of Waterford. In 2022, it had a population of 8,610, making it the fourth-largest t ...

) and 49 other tenant-rights MPs to Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. In November 1852, Lord Derby's short-lived Conservative government introduced a land bill to compensate Irish tenants on eviction for improvements they had made to the land. The bill passed in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

in 1853 and 1854, but failed to win consent of the landed grandees in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

.

What Duffy optimistically hailed as the " League of North and South" unravelled. In the Catholic South, Archbishop Cullen approved the leading Catholic MPs William Keogh and John Sadleir breaking their pledge of independent opposition and accepting positions in a new Whig administration. In the Protestant North William Sharman Crawford

William Sharman Crawford (1780–1861) was an Irish landowner who, in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, championed a democratic franchise, a devolved legislature for Ireland, and the interests of the Irish tenant farmer. As a Radical repres ...

and other League candidates had their meetings broken up by Orange "bludgeon men".

An "Irish Mazzini"

To the cause of tenant rights, Cullen was sympathetic, but of Duffy he was deeply suspicious. Following O'Connell, he described Duffy as an "Irish Mazzini"—condemnation from a man who had witnessed the Church's humiliation under Mazzini'sRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

in 1849. Duffy in turn accused the Church under Cullen of pursuing a "Roman policy" in Ireland "hostile to its nationality."

Until O'Connell's death, Duffy suggested that Rome had "believed in the possibility of an Independent Catholic State" in Ireland, but that since O'Connell's death could "only see the possibility of a Red Republic". The Curia

Curia (: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers, they came to meet ...

had, as a result, returned to "her design of treating Ireland as an entrenched camp of Catholicity in the heart of the British Empire, capable of leavening the whole." Ireland for this purpose had to be"thoroughly imperialised, loyalised, welded into England."

Cullen has been described as the man who "borrowed the British Empire." Under his leadership the Irish church developed an "Hiberno-Roman" mission that was ultimately extended through Britain to the entire English-speaking world. But Cullen's biographers would argue that Duffy travestied Cullen and his church's complex and nuanced relationship to Irish nationalism.—perhaps as much as Cullen caricatured Duffy's separatism.

Australia

Emigration and new political career

The cause of the Irish tenants, and indeed of Ireland generally, seemed to Duffy more hopeless than ever. Broken in health and spirit, he published in 1855 a farewell address to his constituency, declaring that he had resolved to retire from parliament, as it was no longer possible to accomplish the task for which he had solicited their votes. To John Dillon he wrote that an Ireland where McKeogh typified patriotism and Cullen the church was an Ireland in which he could no longer live. In 1856, Duffy and his family emigrated to Australia. After being feted in Sydney and Melbourne, he settled in the newly formedColony of Victoria

The Colony of Victoria was a historical administrative division in Australia that existed from 1851 until 1901, when it federated with other colonies to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Situated in the southeastern corner of the Australian ...

. Duffy was followed to Melbourne by Margaret Callan. Her daughter was later to marry Duffy's eldest son by his first marriage, John Gavan Duffy.

Duffy initially practised law in Melbourne, but a public appeal was soon held to enable him to buy the freehold property necessary to stand for the colonial Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. He was immediately elected to the Legislative Assembly for Villiers and Heytesbury in the Western District in 1856. A ''Melbourne Punch

''Melbourne Punch'' (from 1900, simply titled ''Punch'') was an Australian illustrated magazine founded by Edgar Ray and Frederick Sinnett, and published from August 1855 to December 1925. The magazine was modelled closely on '' Punch'' of Lon ...

'' cartoon depicted Duffy entering Parliament as a bog Irishman carrying a shillelagh atop the parliamentary benches (''Punch'', 4 December 1856, p. 141). He later represented Dalhousie and then North Gippsland.

Duffy's Land Act

Victorian Government

The Victoria State Government, also referred to as the Victorian Government, is the executive government of the Australian state of Victoria.

As a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, the State Government was first formed in 1851 when Vic ...

's Haines Ministry, during 1857, another Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

, John O'Shanassy, unexpectedly became Premier. Duffy was his deputy as well as Commissioner for Public Works, President of the Board of Land and Works, and Commissioner for Crown Lands and Survey. Irish Catholics serving as Cabinet Ministers was hitherto unknown in the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

and Melbourne's Protestant establishment was ill-prepared "to countenance so startling a novelty".

Duffy's Land Act was passed in 1862. Like the Nicholson Act of 1860 which it modified, the Duffy Act provided, in specified areas, for new and extended pastoral leases. It was an effort to break the land-holding monopoly of the so-called "squatter" class. However, the bill had been amended into ineffectiveness by the Legislative Council

A legislative council is the legislature, or one of the legislative chambers, of a nation, colony, or subnational division such as a province or state. It was commonly used to label unicameral or upper house legislative bodies in the Brit ...

so that it was easy for the squatters to employ dummies and extend their control. Duffy's attempts to correct the legislation were defeated. Historian Don Garden commented that "Unfortunately Duffy's dreams were on a higher plane than his practical skills as a legislator and the morals of those opposed to him."

In 1858–59, ''Melbourne Punch'' cartoons linked Duffy and O'Shanassy with images of the French Revolution to undermine their Ministry. One famous ''Punch'' image, "Citizens John and Charles", depicted the pair as French revolutionaries holding the skull and cross bone flag of the so-called ''Victorian Republic''. The O'Shanassy Ministry was defeated at the 1859 election and a new government formed.

Premier of Victoria

In 1871, Duffy led the opposition to Premier Sir James McCulloch's plan to introduce aland tax

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land without regard to buildings, personal property and other improvements upon it. Some economists favor LVT, arguing it does not cause economic inefficiency, and helps reduce economic inequali ...

, on the grounds that it unfairly penalised small farmers. When McCulloch's government was defeated on this issue, Duffy became Premier and Chief Secretary (June 1871 to June 1872). Victoria's finances were in a poor state and he was forced to introduce a tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

bill to provide government revenue, despite his adherence to British free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

principles.

An Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics () are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland, defined by their adherence to Catholic Christianity and their shared Irish ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heritage.The term distinguishes Catholics of Irish descent, particul ...

Premier was very unpopular with the Protestant majority in the colony, and Duffy was accused of favouring Catholics in government appointments, an example being the appointment of John Cashel Hoey, who had been his successor as editor of The Nation, to a position in London. In June 1872, his government was defeated in the Assembly on a confidence motion allegedly motivated by sectarianism. He was succeeded as premier by the conservative James Francis and later resigned the leadership of the liberal party in favour of Graham Berry

Sir Graham Berry, (28 August 1822 – 25 January 1904),

was an Australian colonial politician and the 11th Premier of Victoria. He was one of the most radical and colourful figures in the politics of colonial Victoria, and made the most de ...

.

Speakership and retirement

Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Speaker of the Legislative Assembly is a title commonly held by presiding officers of parliamentary bodies styled legislative assemblies. The office is most widely used in state and territorial legislatures in Australia, and in provincial and terr ...

, a post he held without much enthusiasm until handing it over to Peter Lalor

Peter Fintan Lalor ( ); 5 February 1827 – 9 February 1889) was an Irish-Australian rebel and, later, politician, who rose to fame for his leading role in the Eureka Rebellion, an event identified with the "birth of democracy" in Austra ...

, the younger brother of James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor (in Irish, Séamas Fionntán Ó Leathlobhair) (10 March 1809 – 27 December 1849) was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation (Yo ...

, in 1880. Thereafter he quit politics and retired to southern France where he wrote his memoirs: ''The League of North and South, 1850–54'' (1886) and ''My Life in Two Hemispheres'' (1898).

In exile in France, Duffy was an enthusiastic supporter of the Melbourne Celtic Club, which aimed to promote Irish Home Rule

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

and Irish culture. His sons also became members of the club.

In recognition of his services to Victoria, he was knighted in 1873 and made in 1877. He married for a third time in Paris in 1881, to Louise Hall, and they had four more children.

Marriages and children

In 1842, Duffy married Emily McLaughlin (1820–1845), with whom he had two children, one of whom survived, his son John Gavan Duffy. Emily died in 1845. In 1846 he married his cousin from Newry, Susan Hughes (1827–1878), with whom he had eight children, six of whom survived. After Susan died in 1878, he married for a third time, in Paris in 1881, to Louise Hall (1858–1889) by whom had two further children. Of his eight surviving children: * John Gavan Duffy (1844–1917) was a Victorian politician who served variously as Minister for Agriculture, Attorney-General, and Postmaster-General. * Sir Frank Gavan Duffy (1852–1936), was Chief Justice of theHigh Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the apex court of the Australian legal system. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified in the Constitution of Australia and supplementary legislation.

The High Court was establi ...

1931–35.

* Sir Charles Cashel Gavan Duffy (1855-1932) was clerk of the Australian House of Representatives in 1901-17 and of the Senate in 1917-20.

* Philip Cormac Gavan Duffy (1862–1954), a surveyor and civil engineer noted for his work in Western Australia on the Coolgardie water supply,

* Louise Gavan Duffy (1884–1969) was the joint secretary of the nationalist women's organization, Cumann na mBan, and was an Irish republican present at the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

and an Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

enthusiast who founded an Irish language school, Scoil Bhride (St Bridget)'s Girls School in Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin.

* George Gavan Duffy

George Gavan Duffy (21 October 1882 – 10 June 1951) was an Irish politician, barrister and judge who served as President of the High Court from 1946 to 1951, a Judge of the High Court from 1936 to 1951 and Minister for Foreign Affairs from ...

(1882-1951) was an Irish politician and a signatory to the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

in 1921. From 1936 onward he was a justice on the Irish High Court, becoming its president from 1946 until his death in 1951. One year before his death, he heard the ''Tilson Case'', in which he applied the notorious ''ne temere

was a Papal bull, decree issued in 1907 by the Roman Catholic Congregation of the Council regulating the canon law of the Church regarding marriage for practising Catholics. It is named for its incipit, opening words, which literally mean "lest ...

'' decree to the letter as de Valera's 1937 Irish Constitution gave the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland

The Catholic Church in Ireland, or Irish Catholic Church, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church in Full communion, communion with the Holy See. With 3.5 million members (in the Republic of Ireland), it is the largest Christianity in Ir ...

a "special position".

A grandson, Sir Charles Leonard Gavan Duffy, was a judge on the Supreme Court of Victoria

The Supreme Court of Victoria is the highest court in the Australian state of Victoria. Founded in 1852, it is a superior court of common law and equity, with unlimited and inherent jurisdiction within the state.

The Supreme Court compri ...

, Australia.

Death

Sir Charles Gavan Duffy died inNice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in 1903, aged 86.

He is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery

Glasnevin Cemetery () is a large cemetery in Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland which opened in 1832. It holds the graves and memorials of several notable figures, and has a museum.

Location

The cemetery is located in Glasnevin, Dublin, in two part ...

in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

.

Works

Notes

References

* Browne, Geoff, ''A Biographical Register of the Victorian Parliament, 1900–84'', Government Printer, Melbourne, 1985. * Duffy, Charles Gavan. ''Four Years of Irish History 1845–1849'', Robertson, Melbourne, 1883. (autobiography and recollections) * Garden, Don. ''Victoria: A History'', Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1984. * Keatinge, Patrick, 'The Formative Years of the Irish Diplomatic Service', ''Éire-Ireland'', 6, 3 (Autumn 1971), pp. 57–71. * McCarthy, Justin. ''History of Our Own Times'', Vols 1–4, 1895. * McCaughey, Davis. et al. ''Victoria's Colonial Governors 1839–1900'', Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1993. * O'Brien, Antony. ''Shenanigans on the Ovens Goldfields: the 1859 election'', Artillery Publishing, Hartwell, 2005, (p. xi & Ch.2) * Thompson, Kathleen and Serle, Geoffrey. ''A Biographical Register of the Victorian Parliament, 1856–1900'', Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1972. * Wright, Raymond. ''A People's Counsel. A History of the Parliament of Victoria, 1856–1990'', Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992.Further reading

The Politics of Irish Literature: from Thomas Davis to W.B. Yeats, Malcolm Brown

Allen & Unwin, 1973. * John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press. * Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son 1922. * Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher His Political and Military Career, Capt. W. F. Lyons, Burns Oates & Washbourne Limited 1869 * Young Ireland and 1848, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1949. * Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator, Dennis Gwynn, Hutchinson & Co, Ltd. * O'Connell Davis and the Colleges Bill, Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1948. * Smith O'Brien And The "Secession", Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press * Meagher of The Sword, Edited By Arthur Griffith, M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd. 1916. * Young Irelander Abroad The Diary of Charles Hart, Edited by Brendan O'Cathaoir, University Press. * John Mitchel First Felon for Ireland, Edited By Brian O'Higgins, Brian O'Higgins 1947. * Rossa's Recollections 1838 to 1898, Intro by Sean O'Luing, The Lyons Press 2004. * Labour in Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1910. * The Re-Conquest of Ireland, James Connolly, Fleet Street 1915. * John Mitchel Noted Irish Lives, Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd 1934. * Thomas Davis: Essays and Poems, Centenary Memoir, M. H Gill, M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd MCMXLV. * Life of John Martin, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy & Co., Ltd 1901. * Life of John Mitchel, P. A. Sillard, James Duffy and Co., Ltd 1908. * John Mitchel, P. S. O'Hegarty, Maunsel & Company, Ltd 1917. * The Fenians in Context Irish Politics & Society 1848–82, R. V. Comerford, Wolfhound Press 1998 * William Smith O'Brien and the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848, Robert Sloan, Four Courts Press 2000 * Irish Mitchel, Seamus MacCall, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1938. * Ireland Her Own, T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd 1976. * Life and Times of Daniel O'Connell, T. C. Luby, Cameron & Ferguson. * Young Ireland, T. F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945. * Irish Rebel John Devoy and America's Fight for Irish Freedom, Terry Golway, St. Martin's Griffin 1998. * Paddy's Lament Ireland 1846–1847 Prelude to Hatred, Thomas Gallagher, Poolbeg 1994. * The Great Shame, Thomas Keneally, Anchor Books 1999. * James Fintan Lalor, Thomas, P. O'Neill, Golden Publications 2003. * Charles Gavan Duffy: Conversations With Carlyle (1892), with Introduction, Stray Thoughts on Young Ireland, by Brendan Clifford, Athol Books, Belfast, . (Pg. 32 Titled, Foster's account of Young Ireland.) * Envoi, Taking Leave of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork. * The Falcon Family, or, Young Ireland, by M. W. Savage, London, 1845.

An Gorta Mor

''Quinnipiac University''

External links

* * * *{{DEFAULTSORT:Duffy, Charles Gavan 1816 births 1903 deaths Australian federationists Irish emigrants to colonial Australia Irish knights Irish male poets Australian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian Knights Bachelor Young Irelanders 19th-century Irish businesspeople Activists for Irish land reform Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wexford constituencies (1801–1922) Irish newspaper editors UK MPs 1852–1857 Politicians from County Monaghan Premiers of Victoria Victoria (state) state politicians Irish newspaper founders Speakers of the Victorian Legislative Assembly People educated at St Malachy's College 19th-century Irish poets 19th-century Australian journalists 19th-century Australian male writers Alumni of King's Inns Australian male journalists Members of the Victorian Legislative Assembly Presidents of the Board of Land and Works Chief secretaries of Victoria Ministers for public works (Victoria) People from Monaghan (town) Writers from County Monaghan Commissioners of crown lands and survey (Victoria) Businesspeople awarded knighthoods