Charles Dewey Day on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Dewey Day, (May 6, 1806 – January 31, 1884) was a lawyer, political figure, and judges in

/ref> Day studied in Montreal, articled in law, and was called to the

As a result of the Lower Canada Rebellion, and the similar rebellion in Upper Canada (now

As a result of the Lower Canada Rebellion, and the similar rebellion in Upper Canada (now

In 1859, Day was appointed to the three-person commission to develop the ''

In 1859, Day was appointed to the three-person commission to develop the ''

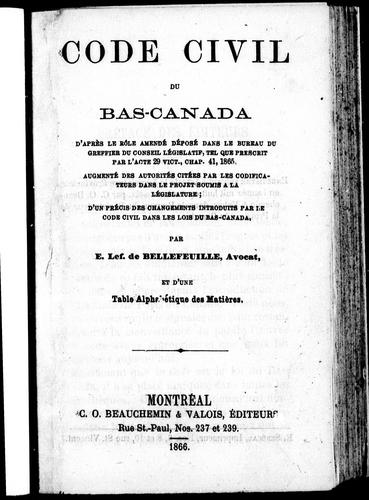

/ref> The commissioners worked for six years on the project. When Morin died in 1865, he was replaced by Joseph-Ubalde Beaudry for the remaining term of the Commission. Day was the main author of the portion of the proposed code dealing with commercial law, which was his legal specialty. His work became the fourth book of the ''Civil Code of Lower Canada'', entitled "Commercial Law". He also wrote a substantial portion of "Book Third, Of the Acquisition and Exercise of Rights of Property". The commissioners completed their work in 1865 and submitted the draft of the code to Parliament. By a statute passed in 1865, the Parliament approved the draft code, with a number of corrections and additions for the commissioners to review. In 1866, the provincial Cabinet passed an order-in-council authorising the Governor General to proclaim the ''Code'' in force on August 1, 1866. By the time of its enactment, shortly before

Day was strongly interested in improving educational facilities in Lower Canada. As early as 1836, he had joined a Montreal committee formed to improve education in the province. It included amongst its members several who would become leaders in the Patriote movement. From 1842 to 1852 he was the vice-president of the Anglican Church Society, possibly because of the Society's educational goals. In 1869 he was appointed to the Quebec Council of Public Instruction, serving from 1868 to 1875 as the chairman of the Council's Protestant Committee.

From 1852 to 1884, Day served as president of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning in the province. The Institution was an umbrella body that provided funding for a variety of educational facilities in the province, including McGill College (now

Day was strongly interested in improving educational facilities in Lower Canada. As early as 1836, he had joined a Montreal committee formed to improve education in the province. It included amongst its members several who would become leaders in the Patriote movement. From 1842 to 1852 he was the vice-president of the Anglican Church Society, possibly because of the Society's educational goals. In 1869 he was appointed to the Quebec Council of Public Instruction, serving from 1868 to 1875 as the chairman of the Council's Protestant Committee.

From 1852 to 1884, Day served as president of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning in the province. The Institution was an umbrella body that provided funding for a variety of educational facilities in the province, including McGill College (now

Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

and Canada East

Canada East () was the northeastern portion of the Province of Canada. Lord Durham's Report investigating the causes of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions recommended merging those two colonies. The new colony, known as the Province of ...

(now Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

). He was a member of the Special Council of Lower Canada

The Special Council of Lower Canada was an appointed body which administered Lower Canada until the Act of Union (1840), Union Act of 1840 created the Province of Canada. Following the Lower Canada Rebellion, on March 27, 1838, the Constitutional ...

, which governed Lower Canada after the Lower Canada Rebellions in 1837 and 1838. He was elected to the first Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada

The Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada was the lower house of the Parliament of the Province of Canada. The Province of Canada consisted of the former province of Lower Canada, then known as Canada East (now Quebec), and Upper Canada ...

in 1841, but resigned in 1842 to accept an appointment to the Court of Queen's Bench of Lower Canada.

Day also served on the commission for the codification of the civil laws of Lower Canada, which produced the ''Civil Code of Lower Canada

The ''Civil Code of Lower Canada'' () was a law that was in effect in Lower Canada on 1 August 1866 and remained in effect in Quebec until repealed and replaced by the Civil Code of Quebec on 1 January 1994. The Code replaced a mixture of French ...

'', enacted in 1866. Day wrote all of the provisions of the ''Civil Code'' relating to commercial law, and most of the provisions relating to property rights. He was later appointed to the federal royal commission investigating the Pacific Scandal

The Pacific Scandal was a political scandal in Canada involving large sums of money paid by private interests to the Conservative Party to cover election expenses in the 1872 Canadian federal election in order to influence the bidding for a natio ...

, whose investigation contributed to the downfall of the federal Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

government of Sir John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (10 or 11January 18156June 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 until his death in 1891. He was the dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, and had a political ...

in 1873.

Day was interested in promoting education throughout his life, and from 1864 to his death in 1884 while visiting England was the first chancellor of McGill College (now McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

).

Family and early legal career

Day was born inBennington, Vermont

Bennington is a New England town, town in Bennington County, Vermont, United States. It is one of two shire towns (county seats) of the county, the other being Manchester (town), Vermont, Manchester. As of the 2020 United States Census, US Cens ...

in 1806, the son of Ithmar Day and Laura Dewey. His father was likely employed by the North-West Company

The North West Company was a Canadian fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in the regions that later became Western Canada and Northwestern Onta ...

. The family moved in 1812 to Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

in Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

, where his father was involved in retail businesses, particularly pharmacies and provisions for the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

. In 1828, the family moved again, this time to Wright's Town, Lower Canada (now Gatineau, Quebec

Gatineau ( ; ) is a city in southwestern Quebec, Canada. It is located on the northern bank of the Ottawa River, directly across from Ottawa, Ontario. Gatineau is the largest city in the Outaouais administrative region of Quebec and is also par ...

), across the Ottawa River from Bytown

Bytown is the former name of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. It was founded on September 26, 1826, incorporated as a town on January 1, 1850, and superseded by the incorporation of the City of Ottawa on January 1, 1855. The founding was marked by a sod ...

(now Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

). His father established a sawmill, fulling-mill and blacksmith shop.Carman Miller, "Day, Charles Dewey", ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography'', Vol. XI (1881-1890), University of Toronto / Université Laval./ref> Day studied in Montreal, articled in law, and was called to the

bar of Lower Canada

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

** Chocolate bar

*Protein bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of ...

in 1827. He practised mainly in the Ottawa valley and represented lumber merchants such as the Wright

Wright is an occupational surname originating in England and Scotland. The term 'Wright' comes from the circa 700 AD Old English word 'wryhta' or 'wyrhta', meaning worker or shaper of wood. Later it became any occupational worker (for example, a ...

family. In 1838, he was named Queen's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

.

Day married twice, first to Barbara Lyon in 1830, with whom he had three children, and then in 1853 to Maria Margaret Holmes, daughter of Benjamin Holmes, a Montreal merchant and political figure.

Political career

Lower Canada

Day’s political career began in 1834, when he spoke publicly against theNinety-Two Resolutions

The Ninety-Two Resolutions were drafted by Louis-Joseph Papineau and other members of the '' Parti patriote'' of Lower Canada in 1834. The resolutions were a long series of demands for political reforms in the British-governed colony.

Papineau ha ...

, passed by the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada

The Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada was the lower house of the bicameral structure of provincial government in Lower Canada until 1838. The legislative assembly was created by the Constitutional Act of 1791. The lower house consisted of e ...

. The Resolutions were drafted by the ''Parti patriote

The () or () was a primarily francophone political party in what is now Quebec founded by members of the liberal elite of Lower Canada at the beginning of the 19th century. Its members were made up of liberal professionals and small-scale ...

'', the nationalist French-Canadian party led by Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau (; October 7, 1786 – September 23, 1871), born in Montreal, Province of Quebec (1763–1791), Quebec, was a politician, lawyer, and the landlord of the ''seigneurie de la Petite-Nation''. He was the leader of the reform ...

. The Resolutions were highly critical of the British government of Lower Canada, particularly the Legislative Council of Lower Canada

The Legislative Council of Lower Canada was the upper house of the Parliament of Lower Canada from 1792 until 1838. The Legislative Council consisted of appointed councillors who voted on bills passed up by the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canad ...

, the appointed upper house

An upper house is one of two Legislative chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house. The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restricted p ...

of the Lower Canada Parliament. The Legislative Council was dominated by British Canadians and frequently rejected measures passed by the elected Legislative Assembly.

Day spoke strongly in favour of maintaining the British connection and opposed what he saw as a revolutionary approach in the Resolutions. He became a leading member of the Montreal Constitutional Committee, which was opposed to the Resolutions. He also was elected to a significant position on a committee formed to draft an address to the monarch and the British government outlining the political views of the anglophone business community in Montreal.

The political tensions in Lower Canada led to the Lower Canada Rebellions of 1837–1838. Day was appointed deputy judge advocate, and presided over some of the trials of ''Patriote'' rebels. In 1840, Day was appointed to the Special Council of Lower Canada

The Special Council of Lower Canada was an appointed body which administered Lower Canada until the Act of Union (1840), Union Act of 1840 created the Province of Canada. Following the Lower Canada Rebellion, on March 27, 1838, the Constitutional ...

, which the British government created to govern the province, after it suspended the Lower Canada Parliament following the Rebellion. Day was also appointed solicitor-general of Lower Canada.

Province of Canada

As a result of the Lower Canada Rebellion, and the similar rebellion in Upper Canada (now

As a result of the Lower Canada Rebellion, and the similar rebellion in Upper Canada (now Ontario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

), the British government merged Lower Canada and Upper Canada into a single Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

in 1841. The separate parliaments were abolished and replaced by a single parliament for the entire province, composed of an elected Legislative Assembly and an appointed Legislative Council

A legislative council is the legislature, or one of the legislative chambers, of a nation, colony, or subnational division such as a province or state. It was commonly used to label unicameral or upper house legislative bodies in the Brit ...

. The Governor General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

retained a strong position in the government.

Day was invited by Governor General Lord Sydenham, to join the Executive Council as solicitor-general for Canada East (the new name for Lower Canada), on condition that he hold a seat in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada

The Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada was the lower house of the Parliament of the Province of Canada. The Province of Canada consisted of the former province of Lower Canada, then known as Canada East (now Quebec), and Upper Canada ...

, the elected lower house of the Parliament. In the general elections of 1841, Day was a candidate in the Canada East constituency of Ottawa County. He was supported by Ottawa timber merchants such as Ruggles Wright, and campaigned in favour of the union of the two Canadas. Day won the seat, but the election was hotly contested. His committee's election costs were approximately £1,580.

Day's appointment to the Executive Council triggered a dispute between Lord Sydenham and Robert Baldwin

Robert Baldwin (May 12, 1804 – December 9, 1858) was an Upper Canadian lawyer and politician who with his political partner Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine of Lower Canada, led the first responsible government ministry in the Province of Canada. ...

, also a member of the Council and one of the leaders of the Reform group in the new Parliament. Baldwin's focus was on instituting a system of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

, where the Governor General would appoint the Executive Council from the group with a majority in the Legislative Assembly. As part of that policy, Baldwin wanted to ensure francophone Reformers from Lower Canada would be in the Council. Sydenham opposed Baldwin's plan. His policy was to retain as much control as possible over the government, and not to include a French-Canadian party in the Council. Baldwin wrote to Sydenham, protesting the inclusion of Day and other Government Tories, and the exclusion of French-Canadian representatives. Sydenham treated the letter as a resignation: Baldwin was out, and Day stayed in the Executive Council. It was the first skirmish in the battle for responsible government.

The first session of the new Legislative Assembly began with a motion on the union of the two Canadas. Day voted in favour of the union, along with the other Government Tories from Lower Canada. During the session, he was a consistent supporter of Governor General Lord Sydenham.

As solicitor-general, Day introduced a ''Common Schools Act'', which included grants from the provincial government to support primary schools throughout the province. The ''Common Schools Act'' was the beginning of public education in the province, and also the beginning of separate schools

In Canada, a separate school is a type of school that has constitutional status in three provinces (Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan) and statutory status in the three territories (Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut). In these Canadian ...

on religious lines, which eventually became entrenched in the ''British North America Act, 1867'' (now the ''Constitution Act, 1867

The ''Constitution Act, 1867'' ( 30 & 31 Vict. c. 3) (),''The Constitution Act, 1867'', 30 & 31 Victoria (U.K.), c. 3, http://canlii.ca/t/ldsw retrieved on 2019-03-14. originally enacted as the ''British North America Act, 1867'' (BNA Act), ...

'').

Sydenham died suddenly at the end of the first session. The following year, in 1842, the new governor general, Sir Charles Bagot

Sir Charles Bagot, (23 September 1781 – 19 May 1843) was a British politician, diplomat and colonial administrator. He served as ambassador to the United States, Russia, and the Netherlands. He served as the second Governor General of Cana ...

, was trying to reconstruct the ministry to better reflect the composition of the Legislative Assembly. He offered Day an appointment to the Court of Queen's Bench of Lower Canada, which Day took, resigning from the government. his resignation created a vacancy in the Executive Council, but Bagot had trouble finding a French-Canadian to fill the position. The Reformers of Lower Canada acted as a group, seeking to gain group representation for French Canadians in the Executive Council, not the occasional individual appointment.

Later legal career

Judicial positions

Day was initially appointed to the Court of Queen’s Bench of Lower Canada in 1842. Eight years later, in 1850, he was appointed to theSuperior Court

In common law systems, a superior court is a court of general jurisdiction over civil and criminal legal cases. A superior court is "superior" in relation to a court with limited jurisdiction (see small claims court), which is restricted to civil ...

. In 1862, he resigned his position on that court and resumed his legal practice.

''Civil Code of Lower Canada''

In 1859, Day was appointed to the three-person commission to develop the ''

In 1859, Day was appointed to the three-person commission to develop the ''Civil Code of Lower Canada

The ''Civil Code of Lower Canada'' () was a law that was in effect in Lower Canada on 1 August 1866 and remained in effect in Quebec until repealed and replaced by the Civil Code of Quebec on 1 January 1994. The Code replaced a mixture of French ...

''. Up to that point, the civil law of New France and then Lower Canada had been based on French statutes, royal decrees, and the customary law from the Paris area, the ''coutume de Paris''. Those sources of the law had become increasingly outdated, particularly after France adopted the ''Code Napoléon'', which replaced the older sources of law in France. George-Étienne Cartier

Sir George-Étienne Cartier, 1st Baronet, (pronounced ; September 6, 1814May 20, 1873) was a Canadians, Canadian statesman and Fathers of Confederation, Father of Confederation.

The English spelling of the name—George, instead of Georges, th ...

, the joint premier for Lower Canada, appointed Day and two other Lower Canada judges, René-Édouard Caron

René-Édouard Caron (21 October 1800 – 13 December 1876) was a Canadian politician, judge, and the List of lieutenant governors of Quebec#Lieutenant Governors of Quebec, 1867–present, second Lieutenant Governor of Quebec.

He was born ...

and Augustin-Norbert Morin

Augustin-Norbert Morin (; October 13, 1803 – July 27, 1865) was a Canadien journalist, lawyer, politician, and rebel in Lower Canada. He was a member of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada in the 1830s, as a leading member of the '' ...

, to the commission. Their mandate was to review the civil laws of Lower Canada and prepare a draft civil code for enactment by the Parliament of the Province of Canada

The Parliament of the Province of Canada was the legislature for the Province of Canada, made up of the two regions of Canada West (formerly Upper Canada, later Ontario) and Canada East (formerly Lower Canada, later Quebec).

Creation of the Parl ...

.John E.C. Brierley, "Quebec's Civil Law Codification" (1968), 14:4 McGill LJ 521–589./ref> The commissioners worked for six years on the project. When Morin died in 1865, he was replaced by Joseph-Ubalde Beaudry for the remaining term of the Commission. Day was the main author of the portion of the proposed code dealing with commercial law, which was his legal specialty. His work became the fourth book of the ''Civil Code of Lower Canada'', entitled "Commercial Law". He also wrote a substantial portion of "Book Third, Of the Acquisition and Exercise of Rights of Property". The commissioners completed their work in 1865 and submitted the draft of the code to Parliament. By a statute passed in 1865, the Parliament approved the draft code, with a number of corrections and additions for the commissioners to review. In 1866, the provincial Cabinet passed an order-in-council authorising the Governor General to proclaim the ''Code'' in force on August 1, 1866. By the time of its enactment, shortly before

Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

in 1867, the ''Code'' was seen as an important statement of Quebec's control over its own legal system in the new country. Thomas McCord, who had been one of the secretaries to the commission, produced one of the first commercial versions of the ''Civil Code''. In his preface, he wrote:

The ''Civil Code of Lower Canada'' remained the statement of Quebec's civil law for over a century, until the enactment of the ''Civil Code of Québec'' in 1991, which replaced the old code.

Arbitrator under the ''Constitution Act, 1867''

After Confederation in 1867, the province ofQuebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

appointed Day as their representative on the arbitration board set up to divide the assets and liabilities of the former Province of Canada between the new provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

Counsel before the British-American Joint Commission

In 1869, Day was retained by theHudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

to argue its case before the British-American Joint Commission appointed under a treaty between the two countries, signed in 1864, respecting property claims in the Oregon country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

(referred to as the Columbia district

The Columbia District was a fur-trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, in both the United States and British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the temporarily jointly occupi ...

by Britain). The Hudson's Bay Company and its subsidiary, the Puget Sound Agricultural Company The Puget Sound Agricultural Company (PSAC), with common variations of the name including Puget Sound or Puget's Sound, was a subsidiary joint stock company formed in 1840 by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Its stations operated within the Pacific N ...

, had operated in the area that Britain ceded to the United States by the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to ...

of 1846. The Oregon Treaty stated that they were entitled to fair compensation for their lands. The 1864 treaty set up the joint commission to adjudicate the claims.

Day appeared before the commission in Washington, DC on behalf of the Hudson's Bay Company. He argued that the Company was entitled to $1,388,703.33. However, the final award was $200,000.

Royal Commission on the Pacific Scandal

In 1873, Day was appointed chair of theRoyal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

which investigated charges of corruption against the federal government in the Pacific Scandal

The Pacific Scandal was a political scandal in Canada involving large sums of money paid by private interests to the Conservative Party to cover election expenses in the 1872 Canadian federal election in order to influence the bidding for a natio ...

. The commission’s mandate was to investigate allegations that the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

under Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald had agreed to give the contract for the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

to Sir Hugh Allan

Sir Hugh Allan (September 29, 1810 – December 9, 1882) was a Scottish-Canadian shipping magnate, financier and capitalist. By the time of his death, the Allan Line Royal Mail Steamers, Allan Shipping Line had become the largest privately o ...

, owner of the Allan steamship line, in exchange for substantial campaign donations to the Conservatives in the 1872 federal election.

Day was proposed as a possible chair for the commission by Sir Hector-Louis Langevin

Sir Hector-Louis Langevin, (August 25, 1826 – June 11, 1906) was a Canadian lawyer, politician, and one of the Fathers of Confederation.

Early life and education

Langevin was born in Quebec City in 1826. He studied law and was called to ...

, the federal Minister of Public Works, who had sounded Day out and found that he was generally sympathetic to the position of the Macdonald government. The other members of the commission were two judges, Antoine Polette

Antoine Polette (August 24, 1807 – January 6, 1887) was a Quebec lawyer, judge and political figure.

He was born Antoine Paulet in Pointe-aux-Trembles, Lower Canada in 1807 and studied at the Petit Séminaire de Québec. He articled in law ...

and James Robert Gowan

Sir James Robert Gowan, (December 22, 1815 – March 18, 1909) was a Canadian lawyer, judge, and senator.

Born in Cahore, County Wexford, Ireland, the son of Henry Hatton Gowan and Elizabeth Burkitt, he was educated privately in Dublin. In ...

.

The Liberal opposition boycotted the commission proceedings, because they had wanted an inquiry by a parliamentary committee. As a result, only witnesses proposed by the government were called, and only Prime Minister Macdonald cross-examined them. The witnesses' testimony was often evasive, and the commissioners did not ask many questions of the witnesses.

The commission did not make any findings, but simply filed the transcripts of the evidence with Parliament, when it returned following a prorogation

Prorogation in the Westminster system of government is the action of proroguing, or interrupting, a parliament, or the discontinuance of meetings for a given period of time, without a dissolution of parliament. The term is also used for the period ...

. Day met personally with the Governor General, Lord Dufferin

Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, (21 June 182612 February 1902), was a British public servant and prominent member of Victorian society. In his youth he was a popular figure in the court of Queen Victoria, ...

, for two days and went over the evidence with him. Dufferin concluded that the evidence cleared Macdonald of personal corruption, and of any knowledge of the key point, that Allan had covert arrangements with American financiers for control of the proposed railway. However, on one point, Macdonald admitted that the Conservatives had used some of the money received from Allan for improper election expenses.Berton, ''The National Dream'', pp. 124–125.

The opposition Liberals relied on the evidence of the commission in the subsequent debates in Parliament, which ended with the resignation of the Conservative government and the installation of a Liberal government, led by Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie.

Promoter of education

McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

). As a member of the board of the Institute, he helped with changes to the governing legislation which established McGill College as independent entity, although still affiliated with the Institute. He was the principal ''pro tem'' of the College from 1853 to 1855. From 1864 to 1884, he served as chancellor of McGill and helped establish the McGill Law School

The Faculty of Law is one of the professional graduate schools of McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is the oldest law school in Canada. 180 candidates are admitted for any given academic year. For the year 2021 class, the acce ...

.

Death

Day died during a visit to England in 1884, aged 77.See also

1st Parliament of the Province of Canada

The First Parliament of the Province of Canada was summoned in 1841, following the union of Upper Canada and Lower Canada as the Province of Canada on February 10, 1841. The Parliament continued until dissolution in late 1844.

The Parliament ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Day, Charles Dewey 1806 births 1884 deaths 19th-century Canadian judges American emigrants to pre-Confederation Quebec Canadian Anglicans Canadian King's Counsel Chancellors of McGill University Immigrants to Lower Canada Judges in Canada East, Province of Canada Lawyers in Quebec Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada from Canada East Members of the Special Council of Lower Canada People from Bennington, Vermont Principals of McGill University