Characters (Theophrastus) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes,

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes,

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of

Vol 1

�

Vol 2

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 6–9; Treatise on Odours; Concerning Weather Signs.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1926. Loeb Classical Library. ** * . Translated to French by Suzanne Amigues. Paris, Les Belles Lettres. 1988–2006. 5 tomes. Tome 1, Livres I-II. 1988. LVIII-146 p. Tome II, Livres III-IV. 1989. 306 p. Tome III, Livres V-VI. 1993. 212 p. Tome IV, Livres VII-VIII, 2003. 238 p. Tome V, Livres IX. 2006. LXX-400 p. First edition in French. Identifications are up-to-date, and carefully checked with botanists. Greek names with identifications are o

Pl@ntUse

* . Translated by B. Einarson and G. Link, 1989–1990. Loeb Classical Library. 3 volumes: , , .

*

Translated by R. C. Jebb

1870. *

Translated by J. M. Edmonds

1929, with parallel text. ** Translated by J. Rusten, 2003. Loeb Classical Library. * ''On Sweat, On Dizziness and On Fatigue.'' Translated by W. Fortenbaugh, R. Sharples, M. Sollenberger. Brill 2002. * ''On Weather Signs.'' *

Translated by J. G. Wood, G. J. Symons

1894. ** Edited by Sider David and Brunschön Carl Wolfram. Brill 2007. *

On Stones

'

International Theophrastus Project

started by

Works by Theophrastus at Perseus Digital Library

* * * * * —Contains a translation of ''On the Senses'' by Theophrastus. * *

Project ''Theophrastus''

Online Galleries, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Theophrastus of Eresus at the Edward Worth Library, Dublin

Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, Hort's English translation of 1916

as html tagged with geolocated place references, a

ToposText

* * {{Authority control 370s BC births 280s BC deaths 4th-century BC Greek philosophers 4th-century BC philosophers 3rd-century BC Greek philosophers Ancient Eresians Ancient Greek biologists Ancient Greek botanists Ancient Greek ethicists Ancient Greek logicians Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greek science writers Peripatetic philosophers Natural philosophers Ancient Greek grammarians Hellenistic-era philosophers in Athens Metic philosophers in Classical Athens

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. A native of Eresos

Eresos (; ; ) and its twin beach village Skala Eresou are located in the southwest part of the Greek island of Lesbos. They are villages visited by considerable numbers of tourists. From 1999 until 2010, Eresos and the village of Antissa const ...

in Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, he was Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

, the Peripatetic school of philosophy in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. Theophrastus wrote numerous treatises across all areas of philosophy, working to support, improve, expand, and develop the Aristotelian system. He made significant contributions to various fields, including ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

, botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, and natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. Often considered the "father of botany" for his groundbreaking works "Enquiry into Plants

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the w ...

" () and "On the Causes of Plants", () Theophrastus established the foundations of botanical science. His given name was (Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: ); the nickname Theophrastus ("divine speaker") was reputedly given to him by Aristotle in recognition of his eloquent style.

He came to Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

at a young age and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death, he attached himself to Aristotle who took to Theophrastus in his writings. When Aristotle fled Athens, Theophrastus took over as head of the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

. Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for thirty-six years, during which time the school flourished greatly. He is often considered the father of botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

for his works on plants. After his death, the Athenians honoured him with a public funeral. His successor as head of the school was Strato of Lampsacus

Strato of Lampsacus (; , – ) was a Peripatetic philosopher, and the third director ( scholarch) of the Lyceum after the death of Theophrastus. He devoted himself especially to the study of natural science, and increased the naturalistic eleme ...

.

The interests of Theophrastus were wide ranging, including biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

and metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

. His two surviving botanical works, '' Enquiry into Plants (Historia Plantarum)'' and ''On the Causes of Plants'', were an important influence on Renaissance science

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, mathematics, manufacturing, anatomy and engineering. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and co ...

. There are also surviving works ''On Moral Characters'', ''On Sense Perception'', and ''On Stones'', as well as fragments on ''Physics'' and ''Metaphysics''. In philosophy, he studied grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

and language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

and continued Aristotle's work on logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

. He also regarded space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

as the mere arrangement and position of bodies, time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

as an accident of motion, and motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

as a necessary consequence of all activity. In ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, he regarded happiness

Happiness is a complex and multifaceted emotion that encompasses a range of positive feelings, from contentment to intense joy. It is often associated with positive life experiences, such as achieving goals, spending time with loved ones, ...

as depending on external influences as well as on virtue

A virtue () is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be morality, moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is Value (ethics), valued as an Telos, end purpos ...

.

Life

Most of the biographical information about Theophrastus was provided byDiogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

' ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek phi ...

'', written more than four hundred years after Theophrastus's time. He was a native of Eresos

Eresos (; ; ) and its twin beach village Skala Eresou are located in the southwest part of the Greek island of Lesbos. They are villages visited by considerable numbers of tourists. From 1999 until 2010, Eresos and the village of Antissa const ...

in Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

. His given name was Tyrtamus (), but he later became known by the nickname "Theophrastus", given to him, it is said, by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

to indicate the grace of his conversation (from Ancient Greek 'god' and 'to phrase', i.e. divine expression).

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, where he may have studied under Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. He became friends with Aristotle, and when Plato died (348/7 BC) Theophrastus may have joined Aristotle in his self-imposed exile from Athens. When Aristotle moved to Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

on Lesbos in 345/4, it is very likely that he did so at the urging of Theophrastus. It seems that it was on Lesbos that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their research into natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

, with Aristotle studying animals and Theophrastus studying plants. Theophrastus probably accompanied Aristotle to Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

ia when Aristotle was appointed tutor to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

in 343/2. Around 335 BC, Theophrastus moved with Aristotle to Athens, where Aristotle began teaching in the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

. When, after the death of Alexander, anti-Macedonian feeling forced Aristotle to leave Athens, Theophrastus remained behind as head (''scholarch

A scholarch (, ''scholarchēs'') was the head of a school in ancient Greece. The term is especially remembered for its use to mean the heads of schools of philosophy, such as the Platonic Academy in ancient Athens. Its first scholarch was Plato h ...

'') of the Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school ( ) was a philosophical school founded in 335 BC by Aristotle in the Lyceum in ancient Athens. It was an informal institution whose members conducted philosophical and scientific inquiries. The school fell into decline afte ...

, a position he continued to hold after Aristotle's death in 322/1.

Aristotle in his will made him guardian of his children, including Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

, with whom he was close. Aristotle likewise bequeathed to him his library and the originals of his works, and designated him as his successor at the Lyceum. Eudemus of Rhodes

Eudemus of Rhodes (; ) was an ancient Greek philosopher, considered the first historian of science. He was one of Aristotle's most important pupils, editing his teacher's work and making it more easily accessible. Eudemus' nephew, Pasicles, was al ...

also had some claims to this position, and Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum (; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Peripatetic school, Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been lost, but one musi ...

is said to have resented Aristotle's choice.

Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for 35 years, and died at age 85, according to Diogenes.

He is said to have remarked, "We die just when we are beginning to live".

Under his guidance, the school flourished greatly—there were at one period more than 2,000 students, Diogenes affirms—and at his death, according to the terms of his will preserved by Diogenes, he bequeathed to it his garden with house and colonnades as a permanent seat of instruction. The comic poet Menander

Menander (; ; c. 342/341 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek scriptwriter and the best-known representative of Athenian Ancient Greek comedy, New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His record at the Cit ...

was among his pupils. His popularity was shown in the regard paid to him by Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

, Cassander

Cassander (; ; 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and '' de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a contemporary of Alexander the ...

, and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, and by the complete failure of a charge of impiety brought against him. He was honored with a public funeral, and "the whole population of Athens, honouring him greatly, followed him to the grave." He was succeeded as head of the Lyceum by Strato of Lampsacus

Strato of Lampsacus (; , – ) was a Peripatetic philosopher, and the third director ( scholarch) of the Lyceum after the death of Theophrastus. He devoted himself especially to the study of natural science, and increased the naturalistic eleme ...

.

Writings

From the lists of Diogenes, giving 227 titles, it appears that the activity of Theophrastus extended over the whole field of contemporary knowledge. His writing probably differed little from Aristotle's treatment of the same themes, though supplementary in details. Like Aristotle, most of his writings are lost works. Thus Theophrastus, like Aristotle, had composed a first and second ''Analytic'' ( and ). He had also written books on ''Topics'' (, and ); on the ''Analysis of Syllogisms'' ( and ), on ''Sophisms'' () and on ''Affirmation and Denial'' () as well as on the ''Natural Philosophy'' (, , and others), on ''Heaven'' (), and on ''Meteorological Phenomena'' ( and ). In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes,

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes, Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

, Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

, Archelaus, Diogenes of Apollonia

Diogenes of Apollonia ( ; ; 5th century BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher, and was a native of the Milesian colony Apollonia in Thrace. He lived for some time in Athens. He believed air to be the one source of all being from which all oth ...

, Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

, which were made use of by Simplicius; and also on Xenocrates

Xenocrates (; ; c. 396/5314/3 BC) of Chalcedon was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and leader ( scholarch) of the Platonic Academy from 339/8 to 314/3 BC. His teachings followed those of Plato, which he attempted to define more closely, of ...

, against the Academics

Academic means of or related to an academy, an institution learning.

Academic or academics may also refer to:

* Academic staff, or faculty, teachers or research staff

* school of philosophers associated with the Platonic Academy in ancient Greece ...

, and a sketch of the political doctrine of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

.

He studied general history, as we know from Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

's lives of Lycurgus

Lycurgus (; ) was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its (), involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The Spartans i ...

, Solon

Solon (; ; BC) was an Archaic Greece#Athens, archaic History of Athens, Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. ...

, Aristides

Aristides ( ; , ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''díkaios''), he flourished at the beginning of Athens' Classical period and is remembered for his generalship in the Persian War. ...

, Pericles

Pericles (; ; –429 BC) was a Greek statesman and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Ancient Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and was acclaimed ...

, Nicias

Nicias (; ; 470–413 BC) was an Athenian politician and general, who was prominent during the Peloponnesian War. A slaveowning member of the Athenian aristocracy, he inherited a large fortune from his father, and had investments in the silv ...

, Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

, Lysander

Lysander (; ; 454 BC – 395 BC) was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an end. He then played ...

, Agesilaus

Agesilaus II (; ; 445/4 – 360/59 BC) was king of Sparta from 400 to 360 BC. Generally considered the most important king in the history of Sparta, Agesilaus was the main actor during the period of Spartan hegemony that followed the Peloponn ...

, and Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

, which were probably borrowed from the work on ''Lives'' (). But his main efforts were to continue the labours of Aristotle in natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. This is testified to not only by a number of treatises on individual subjects of zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

, of which, besides the titles, only fragments remain, but also by his books ''On Stones'', his ''Enquiry into Plants'', and ''On the Causes of Plants'' (see below), which have come down to us entire. In politics, also, he seems to have trodden in the footsteps of Aristotle. Besides his books on the ''State'' ( and ), we find quoted various treatises on ''Education'' ( and ), on ''Royalty'' (, and ), on the ''Best State'' (), on ''Political Morals'' (), and particularly his works on the ''Laws'' (, and ), one of which, containing a recapitulation of the laws of various barbarian

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

as well as Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

states, was intended to be a companion to Aristotle's outline of ''Politics'', and must have been similar to it. He also wrote on oratory and poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

. Theophrastus, without doubt, departed further from Aristotle in his ethical

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied e ...

writings, as also in his metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

investigations of motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

, the soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

, and God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

.

Besides these writings, Theophrastus wrote several collections of problems, out of which some things at least have passed into the ''Problems

A problem is a difficulty which may be resolved by problem solving.

Problem(s) or The Problem may also refer to:

People

* Problem (rapper), (born 1985) American rapper Books

* ''Problems'' (Aristotle), an Aristotelian (or pseudo-Aristotelian) co ...

'' that have come down to us under the name of Aristotle, and commentaries, partly dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

, to which probably belonged the ''Erotikos'' (), ''Megacles'' (), ''Callisthenes'' (), and ''Megarikos'' (), and letters, partly books on mathematical

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

sciences and their history.

Many of his surviving works exist only in fragmentary form. "The style of these works, as of the botanical books, suggests that, as in the case of Aristotle, what we possess consists of notes for lectures or notes taken of lectures," his translator Arthur F. Hort remarks. "There is no literary charm; the sentences are mostly compressed and highly elliptical, to the point sometimes of obscurity". The text of these fragments and extracts is often so corrupt that there is a certain plausibility to the well-known story that the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus were allowed to languish in the cellar of Neleus of Scepsis

Neleus of Scepsis (; ), was the son of Coriscus of Scepsis. He was a disciple of Aristotle and Theophrastus, the latter of whom bequeathed to him his library, and appointed him one of his executors. Neleus supposedly took the writings of Aristotle ...

and his descendants.

On plants

The most important of his books are two large botanical treatises, ''Enquiry into Plants

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the w ...

'' (, generally known as ), and ''On the Causes of Plants'' (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: , Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

: ), which constitute the most important contribution to botanical science during antiquity and the Middle Ages, the first systemization of the botanical world; on the strength of these works some, following Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

, call him the "father of botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

".

The ''Enquiry into Plants'' was originally ten books, of which nine survive. The work is arranged into a system whereby plants are classified according to their modes of generation, their localities, their sizes, and according to their practical uses such as foods, juices, herbs, etc. The first book deals with the parts of plants; the second book with the reproduction of plants and the times and manner of sowing; the third, fourth, and fifth books are devoted to trees, their types, their locations, and their practical applications; the sixth book deals with shrubs

A shrub or bush is a small to medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees by their multiple ...

and spiny plants; the seventh book deals with herbs; the eighth book deals with plants that produce edible seeds; and the ninth book deals with plants that produce useful juices, gums

The gums or gingiva (: gingivae) consist of the mucosal tissue that lies over the mandible and maxilla inside the mouth. Gum health and disease can have an effect on general health.

Structure

The gums are part of the soft tissue lining of the ...

, resins

A resin is a solid or highly viscous liquid that can be converted into a polymer. Resins may be biological or synthetic in origin, but are typically harvested from plants. Resins are mixtures of organic compounds, predominantly terpenes. Comm ...

, etc.

''On the Causes of Plants'' was originally eight books, of which six survive. It concerns the growth of plants; the influences on their fecundity; the proper times they should be sown and reaped; the methods of preparing the soil, manuring it, and the use of tools; and of the smells, tastes, and properties of many types of plants. The work deals mainly with the economical uses of plants rather than their medicinal uses, although the latter is sometimes mentioned. A book on wines and a book on plant smells may have once been part of the complete work.

Although these works contain many absurd and fabulous statements, they include valuable observations concerning the functions and properties of plants. Theophrastus observed the process of germination

Germination is the process by which an organism grows from a seed or spore. The term is applied to the sprouting of a seedling from a seed of an angiosperm or gymnosperm, the growth of a sporeling from a spore, such as the spores of fungi, ...

and recognized the significance of climate to plants. Much of the information on the Greek plants may have come from his own observations, as he is known to have travelled throughout Greece, and to have had a botanical garden of his own; but the works also profit from the reports on plants of Asia brought back from those who followed Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

:

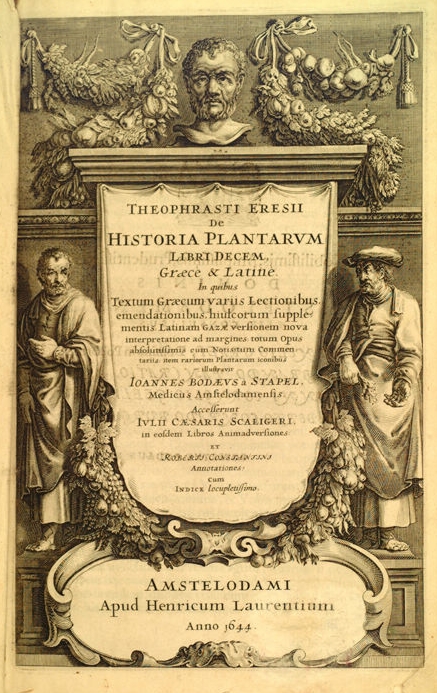

Theophrastus's ''Enquiry into Plants'' was first published in a Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

translation by Theodore Gaza

Theodorus Gaza (, ''Theodoros Gazis''; ; ), also called Theodore Gazis or by the epithet Thessalonicensis and Thessalonikeus (c. 1398 – c. 1475), was a Greek humanist and translator of Aristotle, one of the Greek scholars who were the leader ...

, at Treviso, 1483; in its original Greek it first appeared from the press of Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; ; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and Renaissance humanism, humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preser ...

at Venice, 1495–98, from a third-rate manuscript, which, like the majority of the manuscripts that were sent to printers' workshops in the fifteenth and sixteenth century, has disappeared. Christian Wimmer identified two manuscripts of first quality, the ''Codex Urbinas'' in the Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library (, ), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City, and is the city-state's national library. It was formally established in 1475, alth ...

, which was not made known to J. G. Schneider, who made the first modern critical edition, 1818–21, and the excerpts in the ''Codex Parisiensis'' in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The (; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites, ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national repository of all that is published in France. Some of its extensive collections, including bo ...

.

On moral characters

His book ''Characters'' () contains thirty brief outlines of moral types. They are the first recorded attempt at systematic character writing. The book has been regarded by some as an independent work; others incline to the view that the sketches were written from time to time by Theophrastus, and collected and edited after his death; others, again, regard the ''Characters'' as part of a larger systematic work, but the style of the book is against this. Theophrastus has found many imitators in this kind of writing, notably Joseph Hall (1608), Sir Thomas Overbury (1614–16), Bishop Earle (1628), 17-century poet Samuel Butler (1613), andJean de La Bruyère

Jean de La Bruyère (, , ; 16 August 1645 – 11 May 1696) was a French philosopher and moralist, who was noted for his satire.

Early years

Jean de La Bruyère was born in Paris, in today's Essonne ''département'', in 1645. His family was mi ...

(1688), who also translated the ''Characters''. George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

also took inspiration from Theophrastus's ''Characters'', most notably in her book of caricatures, '' Impressions of Theophrastus Such''. Writing the "character sketch" as a scholastic exercise also originated in Theophrastus's typology.

On sensation

A treatise ''On Sense Perception'' () and its objects is important for a knowledge of the doctrines of the more ancient Greek philosophers regarding the subject. A paraphrase and commentary on this work was written byPriscian of Lydia Priscian of Lydia (or Priscianus; ''Prīskiānós ho Lȳdós''; ; fl. 6th century), was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. Two works of his have survived.

Life

A contemporary of Simplicius of Cilicia, Priscian was born in Lydia, probably in the ...

in the sixth century. With this type of work we may connect the fragments on ''Smells'', on ''Fatigue'', on ''Dizziness'', on ''Sweat'', on ''Swooning'', on ''Palsy'', and on ''Honey''.

Physics

Fragments of a ''History of Physics'' () are extant. To this class of work belong the still extant sections on ''Fire'', on the ''Winds'', and on the signs of ''Waters'', ''Winds'', and ''Storms''. Various smaller scientific fragments have been collected in the editions ofJohann Gottlob Schneider

Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider (18 January 1750 – 12 January 1822) was a German classicist and naturalist.

Biography

Schneider was born at Collm in Saxony. In 1774, on the recommendation of Christian Gottlob Heine, he became secretary to ...

(1818–21) and Friedrich Wimmer (1842–62) and in Hermann Usener

Hermann Karl Usener (23 October 1834 – 21 October 1905) was a German scholar in the fields of philology and comparative religion.

Life

Hermann Usener was born at Weilburg and educated at its Gymnasium. From 1853 he studied at Heidelberg ...

's ''Analecta Theophrastea''.

Metaphysics

The ''Metaphysics'' (anachronistic Greek title: ), in nine chapters (also known as ''On First Principles''), was considered a fragment of a larger work by Usener in his edition (Theophrastos, ''Metaphysica'', Bonn, 1890), but according to Ross and Fobes in their edition (Theophrastus, ''Metaphysica'', Oxford, 1929), the treatise is complete (p. X) and this opinion is now widely accepted. There is no reason for assigning this work to some other author because it is not noticed inHermippus

Hermippus (; fl. 5th century BC) was the one-eyed Athenian writer of the Old Comedy, who flourished during the Peloponnesian War.

Life

He was the son of Lysis, and the brother of the comic poet Myrtilus. He was younger than Telecleides and old ...

and Andronicus

Andronicus or Andronikos () is a classical Greek name. The name has the sense of "male victor, warrior". Its female counterpart is Andronikè (Ἀνδρονίκη). Notable bearers of the name include:

People

*Andronicus of Olynthus, Greek general ...

, especially as Nicolaus of Damascus

Nicolaus of Damascus (Greek: , ''Nikolāos Damaskēnos''; Latin: ''Nicolaus Damascenus''; – after 4 AD) was a Greek historian, diplomat and philosopher who lived during the Augustan age of the Roman Empire. His name is derived from that of his ...

had already mentioned it.

On stones

In his treatise ''On Stones'' (), which would become a source for other lapidaries until at least theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, Theophrastus classified rocks and gems based on their behavior when heated, further grouping minerals by common properties, such as amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

and magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula . It is one of the iron oxide, oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetism, ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetization, magnetized to become a ...

, which both have the power of attraction..

Theophrastus describes different marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

s; mentions coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

, which he says is used for heating by metal-workers; describes the various metal ores; and knew that pumice stones had a volcanic

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often fo ...

origin. He also deals with precious stones, emeralds

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr., and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991). ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York, ...

, amethysts, onyx

Onyx is a typically black-and-white banded variety of agate, a silicate mineral. The bands can also be monochromatic with alternating light and dark bands. ''Sardonyx'' is a variety with red to brown bands alternated with black or white bands. ...

, jasper

Jasper, an aggregate of microgranular quartz and/or cryptocrystalline chalcedony and other mineral phases, is an opaque, impure variety of silica, usually red, yellow, brown or green in color; and rarely blue. The common red color is due to ...

, etc., and describes a variety of "sapphire" that was blue with veins of gold, and thus was presumably lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color. Originating from the Persian word for the gem, ''lāžward'', lapis lazuli is ...

.

He knew that pearls

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

came from shellfish

Shellfish, in colloquial and fisheries usage, are exoskeleton-bearing Aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrates used as Human food, food, including various species of Mollusca, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish ...

, that coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

came from India, and speaks of the fossilized

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains of organic life. He also considers the practical uses of various stones, such as the minerals necessary for the manufacture of glass; for the production of various pigments of paint such as ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), iron ochre, or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colou ...

; and for the manufacture of plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

.

Many of the rarer minerals were found in mines, and Theophrastus mentions the famous copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

mines of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and the even more famous silver mine

Silver mining is the extraction of silver by mining. Silver is a precious metal and holds high economic value. Because silver is often found in intimate combination with other metals, its extraction requires the use of complex technologies. In ...

s, presumably of Laurium

Lavrio, Lavrion or Laurium (; (later ); from Middle Ages until 1908: Εργαστήρια ''Ergastiria'') is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Greece. It is part of Athens metropolitan area and the seat of the municipality of Lavreotik ...

near Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

– the basis of the wealth of the city – as well as referring to gold mines

Gold mining is the extraction of gold by mining.

Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. The expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface has led to more complex ...

. The Laurium silver mines, which were the property of the state, were usually leased for a fixed sum and a percentage on the working. Towards the end of the fifth century BCE the output fell, partly owing to the Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

n occupation of Decelea

Decelea (, ), ''Dekéleia''), was a deme and ancient village in northern Attica serving as a trade route connecting Euboea with Athens, Greece. It was situated near the entrance of the eastern pass across Mount Parnes, which leads from the north ...

from BCE. But the mines continued to be worked, though Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

( BCE to CE) records that in his time the tailings were being worked over, and Pausanias ( to ) speaks of the mines as a thing of the past. The ancient workings, consisting of shafts and galleries for excavating the ore, and washing tables for extracting the metal, may still be seen. Theophrastus wrote a separate work ''On Mining'', which – like most of his writings – is a lost work.

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

makes clear references to his use of ''On Stones'' in his ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' () is a Latin work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work' ...

'' of 77 AD, while updating and making much new information available on minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): M ...

himself. Although Pliny's treatment of the subject is more extensive, Theophrastus is more systematic and his work is comparatively free from fable and magic, although he did describe lyngurium

Lyngurium or Ligurium is the name of a mythical gemstone believed to be formed of the solidified urine of the lynx (the best ones coming from wild males). It was included in classical and "almost every medieval lapidary" or book of gems until it g ...

, a gemstone supposedly formed of the solidified urine of the lynx

A lynx ( ; : lynx or lynxes) is any of the four wikt:extant, extant species (the Canada lynx, Iberian lynx, Eurasian lynx and the bobcat) within the medium-sized wild Felidae, cat genus ''Lynx''. The name originated in Middle Engl ...

(the best ones coming from wild males), which featured in many lapidaries until it gradually disappeared from view in the 17th century.

It is mistakenly attributed to Theophrastus the first record of pyroelectricity. The misconception arose soon after the discovery of the pyroelectric properties of tourmaline

Tourmaline ( ) is a crystalline silicate mineral, silicate mineral group in which boron is chemical compound, compounded with chemical element, elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. This gemstone comes in a ...

, which made mineralogists of the time associate the ''lyngurium

Lyngurium or Ligurium is the name of a mythical gemstone believed to be formed of the solidified urine of the lynx (the best ones coming from wild males). It was included in classical and "almost every medieval lapidary" or book of gems until it g ...

'' with it. Lyngurium

Lyngurium or Ligurium is the name of a mythical gemstone believed to be formed of the solidified urine of the lynx (the best ones coming from wild males). It was included in classical and "almost every medieval lapidary" or book of gems until it g ...

is described in the work of Theophrastus as being similar to amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

, capable of attracting "straws and bits of wood", but without specifying any pyroelectric properties.

Philosophy

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias (; AD) was a Peripatetic school, Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek Commentaries on Aristotle, commentators on the writings of Aristotle. He was a native of Aphrodisias in Caria and liv ...

and Simplicius.

Logic

Theophrastus seems to have carried out still further thegrammatical

In linguistics, grammaticality is determined by the conformity to language usage as derived by the grammar of a particular speech variety. The notion of grammaticality rose alongside the theory of generative grammar, the goal of which is to formu ...

foundation of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

and rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, since in his book on the elements of speech

Speech is the use of the human voice as a medium for language. Spoken language combines vowel and consonant sounds to form units of meaning like words, which belong to a language's lexicon. There are many different intentional speech acts, suc ...

, he distinguished the main parts of speech from the subordinate parts, and also direct expressions ( ) from metaphorical expressions, and dealt with the emotions ( ) of speech. He further distinguished a twofold reference of speech ( ) to things ( ) and to the hearers, and referred poetry and rhetoric to the latter.

He wrote at length on the unity of judgment

Judgement (or judgment) is the evaluation of given circumstances to make a decision. Judgement is also the ability to make considered decisions.

In an informal context, a judgement is opinion expressed as fact. In the context of a legal trial ...

, on the different kinds of negation, and on the difference between unconditional and conditional necessity. In his doctrine of syllogisms

A syllogism (, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

In its earliest form (define ...

he brought forward the proof for the conversion of universal affirmative judgments, differed from Aristotle here and there in the laying down and arranging the ''modi'' of the syllogisms, partly in the proof of them, partly in the doctrine of mixture, i.e. of the influence of the modality of the premises upon the modality of the conclusion. Then, in two separate works, he dealt with the reduction of arguments to the syllogistic form and on the resolution of them; and further, with hypothetical conclusions. For the doctrine of proof

Proof most often refers to:

* Proof (truth), argument or sufficient evidence for the truth of a proposition

* Alcohol proof, a measure of an alcoholic drink's strength

Proof may also refer to:

Mathematics and formal logic

* Formal proof, a co ...

, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

quotes the second ''Analytic'' of Theophrastus, in conjunction with that of Aristotle, as the best treatises on that doctrine. In different monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

s he seems to have tried to expand it into a general theory of science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

. To this, too, may have belonged the proposition quoted from his ''Topics'', that the ''principles of opposites'' are themselves opposed, and cannot be deduced from one and the same higher genus. For the rest, some minor deviations from the Aristotelian definitions are quoted from the ''Topica'' of Theophrastus. Closely connected with this treatise was that upon ambiguous words or ideas, which, without doubt, corresponded to book Ε of Aristotle's ''Metaphysics''.

Physics and metaphysics

Theophrastus introduced his Physics with the proof that all natural existence, being corporeal and composite, requires ''principles'', and first and foremost,motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

, as the basis of all change. Denying the substance of space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

, he seems to have regarded it, in opposition to Aristotle, as the mere arrangement and position ( and ) of bodies. Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

he called an accident of motion, without, it seems, viewing it, with Aristotle, as the numerical determinant of motion. He attacked the doctrine of the four classical elements

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Angola, Tibet, India, ...

and challenged whether fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

could be called a primary element when it appears to be compound, requiring, as it does, another material for its own nutriment.

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only potentially

Potential generally refers to a currently unrealized ability, in a wide variety of fields from physics to the social sciences.

Mathematics and physics

* Scalar potential, a scalar field whose gradient is a given vector field

* Vector potential ...

exists, but he opposed Aristotle's view that motion required a special explanation, and he regarded it as something proper both to nature in general and the celestial system in particular:

He recognised no activity without motion, and so referred all activities of the soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

to motion: the desires and emotions to corporeal motion, judgment () and contemplation to spiritual motion. The idea of a spirit entirely independent of organic activity, must therefore have appeared to him very doubtful; yet he appears to have contented himself with developing his doubts and difficulties on the point, without positively rejecting it. Other Peripatetics, like Dicaearchus

Dicaearchus of Messana (; ''Dikaiarkhos''; ), also written Dikaiarchos (), was a Greek philosopher, geographer and author. Dicaearchus was a student of Aristotle in the Lyceum. Very little of his work remains extant. He wrote on geography and t ...

, Aristoxenus

Aristoxenus of Tarentum (; born 375, fl. 335 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Peripatetic school, Peripatetic philosopher, and a pupil of Aristotle. Most of his writings, which dealt with philosophy, ethics and music, have been lost, but one musi ...

, and especially Strato, developed further this naturalism in Aristotelian doctrine.

Theophrastus seems, generally speaking, where the investigation overstepped the limits of experience, to have preferred to develop the difficulties rather than solve them, as is especially apparent in his ''Metaphysics''. He was doubtful of Aristotle's teleology

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

and recommended that such ideas be used with caution:

He did not follow the incessant attempts by Aristotle to refer phenomena to their ultimate foundations, or his attempts to unfold the internal connections between the latter, and between them and phenomena. In antiquity, it was a subject of complaint that Theophrastus had not expressed himself with precision and consistency respecting God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, and had understood it at one time as Heaven

Heaven, or the Heavens, is a common Religious cosmology, religious cosmological or supernatural place where beings such as deity, deities, angels, souls, saints, or Veneration of the dead, venerated ancestors are said to originate, be throne, ...

, at another an (enlivening) breath (''pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breathing, breath", and in a religious context for "spirit (animating force), spirit". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in rega ...

'').

Ethics

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

. He subordinated moral requirements to the advantage at least of a friend, and had allowed in prosperity the existence of an influence injurious to them. In later times, fault was found with his expression in the ''Callisthenes'', "life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom" ('). That in the definition of pleasure, likewise, he did not coincide with Aristotle, seems to be indicated by the titles of two of his writings, one of which dealt with pleasure generally, the other with pleasure as Aristotle had defined it. Although, like his teacher, he preferred contemplative (theoretical), to active (practical) life, he preferred to set the latter free from the restraints of family life, etc. in a manner of which Aristotle would not have approved.

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. Non-human animals, he said, can reason, sense, and feel just as human beings do.Taylor, Angus. ''Animals and Ethics''. Broadview Press, p. 35.

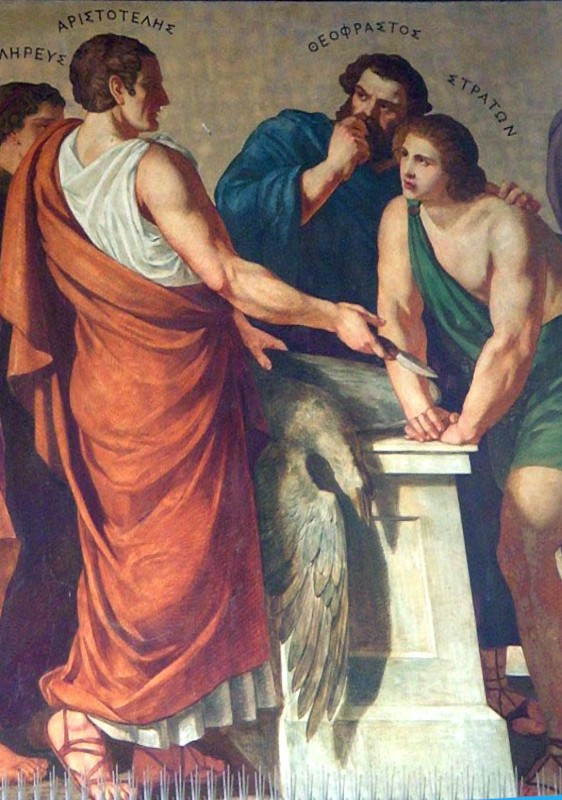

The "portrait" of Theophrastus

The marble herm figure with the bearded head of philosopher type, bearing the explicit inscription, must be taken as purely conventional. Unidentified portrait heads did not find a ready market in post-Renaissance Rome. This bust was formerly in the collection of marchese Pietro Massimi at Palazzo Massimi and belonged to marchese L. Massimi at the time the engraving was made. It is now in theVilla Albani

The Villa Albani (later Villa Albani-Torlonia) is a villa in Rome, built on the Via Salaria for Cardinal Alessandro Albani. It was built between 1747 and 1767 by the architect Carlo Marchionni in a project heavily influenced by otherssuch as Gi ...

, Rome (inv. 1034). The inscribed bust has often been illustrated in engravings and photographs: a photograph of it forms the frontispiece to the Loeb Classical Library

The Loeb Classical Library (LCL; named after James Loeb; , ) is a monographic series of books originally published by Heinemann and since 1934 by Harvard University Press. It has bilingual editions of ancient Greek and Latin literature, ...

''Theophrastus: Enquiry into Plants'' vol. I, 1916. André Thevet

André Thevet (; ; 1516 – 23 November 1590) was a French Franciscan priest, explorer, cosmographer and writer who travelled to the Near East and South America. His most significant book was ''The New Found World, or Antarctike'', which comp ...

illustrated in his iconographic compendium, (Paris, 1584), an alleged portrait plagiarized from the bust, supporting his fraud with the invented tale that he had obtained it from the library of a Greek in Cyprus and that he had seen a confirming bust in the ruins of Antioch.

In popular culture

* "Theophrastus", second middle name of 16th century alchemistParacelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

.

*'' Impressions of Theophrastus Such'', a fictional work by George Eliot, published 1879, comprising character studies ostensibly written by the eponymous Such.

* "Theophrastus", a planet in the 2014 ''Firefly'' graphic novel

A graphic novel is a self-contained, book-length form of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and Anthology, anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comics sc ...

'' Serenity: Leaves on the Wind''.

* "Theophrastus", the given name of Dr. Seuss

Theodor Seuss Geisel ( ;"Seuss"

'' Alchemy Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

experiments to become Theophrastus's apprentice.

'' Alchemy Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

Works

* * * '' Metaphysics'' (or ''On First Principles''). ** Translated by M. van Raalte, 1993, Brill. ** ''On First Principles.'' Translated by Dimitri Gutas, 2010, Brill. * ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 1–5.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1916. Loeb Classical Library.Vol 1

�

Vol 2

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 6–9; Treatise on Odours; Concerning Weather Signs.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1926. Loeb Classical Library. ** * . Translated to French by Suzanne Amigues. Paris, Les Belles Lettres. 1988–2006. 5 tomes. Tome 1, Livres I-II. 1988. LVIII-146 p. Tome II, Livres III-IV. 1989. 306 p. Tome III, Livres V-VI. 1993. 212 p. Tome IV, Livres VII-VIII, 2003. 238 p. Tome V, Livres IX. 2006. LXX-400 p. First edition in French. Identifications are up-to-date, and carefully checked with botanists. Greek names with identifications are o

Pl@ntUse

* . Translated by B. Einarson and G. Link, 1989–1990. Loeb Classical Library. 3 volumes: , , .

*

Translated by R. C. Jebb

1870. *

Translated by J. M. Edmonds

1929, with parallel text. ** Translated by J. Rusten, 2003. Loeb Classical Library. * ''On Sweat, On Dizziness and On Fatigue.'' Translated by W. Fortenbaugh, R. Sharples, M. Sollenberger. Brill 2002. * ''On Weather Signs.'' *

Translated by J. G. Wood, G. J. Symons

1894. ** Edited by Sider David and Brunschön Carl Wolfram. Brill 2007. *

On Stones

'

Modern editions

* ''Theophrastus' Characters: An Ancient Take on Bad Behavior'' by James Romm (author), Pamela Mensch (translator), and André Carrilho (illustrator), Callaway Arts & Entertainment, 2018.Brill

ThInternational Theophrastus Project

started by

Brill Publishers

Brill Academic Publishers () is a Dutch international academic publisher of books, academic journals, and Bibliographic database, databases founded in 1683, making it one of the oldest publishing houses in the Netherlands. Founded in the South ...

in 1992.

* 1. ''Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources for His Life, Writings, Thought and Influence'' (two volumes), edited by William Fortenbaugh ''et al.'', Leiden: Brill, 1992.

** 1.1. ''Life, Writings, Various Reports, Logic, Physics, Metaphysics, Theology, Mathematics'' exts 1–264

** 1.2. ''Psychology, Human Physiology, Living Creatures, Botany, Ethics, Religion, Politics, Rhetoric and Poetics, Music, Miscellanea'' exts 265–741

* ff. 9 volumes are planned; the published volumes are:

** ''1. Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources for His Life, Writings, Thought and Influence — Commentary'', Leiden: Brill, 1994

** ''2. Logic'' exts 68–136 by Pamela Huby (2007); with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas

Dimitri Gutas (; born 1945, in Cairo) is an American Arabist and Hellenist specialized in medieval Islamic philosophy, who serves as professor emeritus of Arabic and Islamic Studies in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations a ...

.

** ''3.1. Sources on Physics (Texts 137–223)'', by R. W. Sharples (1998).

** ''4. Psychology (Texts 265–327)'', by Pamela Huby (1999); with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas.

** ''5. Sources on Biology (Human Physiology, Living Creatures, Botany: Texts 328–435''), by R. W. Sharples (1994).

** ''6.1. Sources on Ethics'' exts 436–579B by William W. Fortenbaugh; with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas (2011).

** ''8. Sources on Rhetoric and Poetics (Texts 666–713)'', by William W. Fortenbaugh (2005); with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas.

** ''9.1. Sources On Music (Texts 714-726C)'', by Massimo Raffa (2018).

** ''9.2. Sources on Discoveries and Beginnings, Proverbs et al. (Texts 727–741)'', by William W. Fortenbaugh (2014).

Explanatory notes

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Attribution: * *Further reading