Catalpa Rescue on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Catalpa'' rescue was the escape, on 17–19 April 1876, of six Irish

The ''Catalpa'' rescue was the escape, on 17–19 April 1876, of six Irish

Between 1865 and 1867, the

Between 1865 and 1867, the

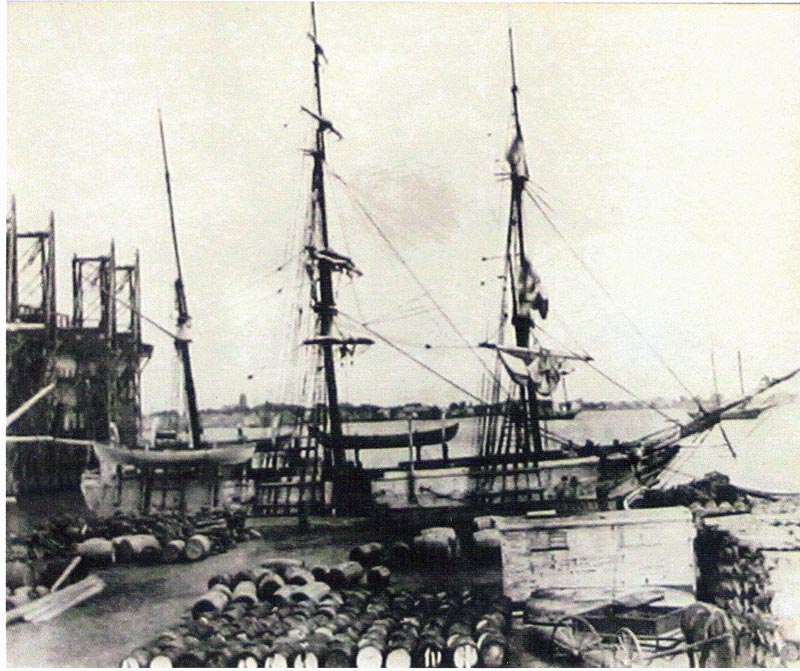

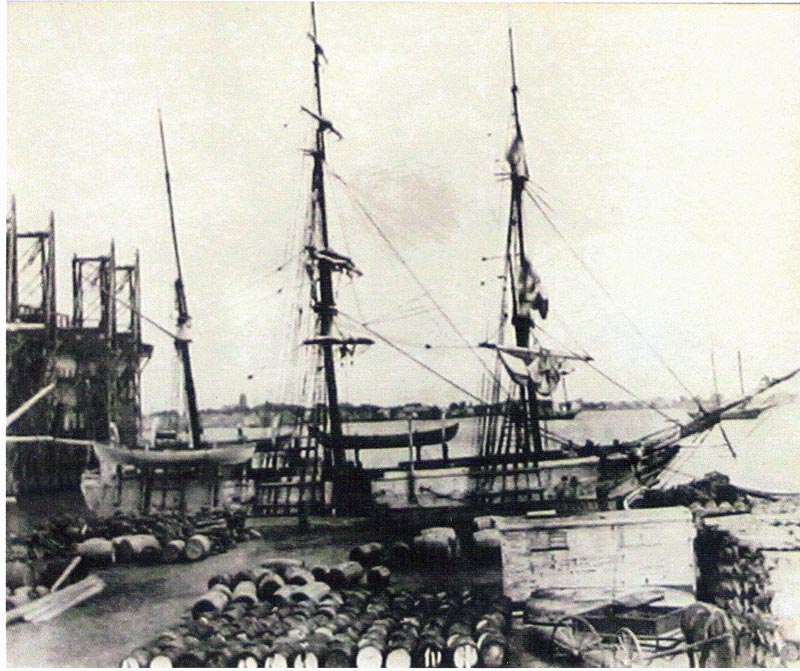

In 1875, the Clan's committee purchased (in the name of their member James Reynolds) three-masted merchant

In 1875, the Clan's committee purchased (in the name of their member James Reynolds) three-masted merchant

The escape had been planned for 6 April, but the appearance of ''Conflict'', other Royal Navy ships and customs officers led to a postponement. The escape was rearranged for 17 April, when most of the Convict Establishment garrison was watching the Perth Yacht Club

The escape had been planned for 6 April, but the appearance of ''Conflict'', other Royal Navy ships and customs officers led to a postponement. The escape was rearranged for 17 April, when most of the Convict Establishment garrison was watching the Perth Yacht Club

On 9 September 2005 a memorial was unveiled in Rockingham to commemorate the escape. The memorial, a large statue of six wild

On 9 September 2005 a memorial was unveiled in Rockingham to commemorate the escape. The memorial, a large statue of six wild

File:MartinHoganConvict.jpg, Martin Hogan (1833–1901)

File:ThomasHassettConvict.jpg, Thomas Hassett (1841–1893)

File:James Wilson.jpg,

View the Memorial Launch Video

*Vincent McDonnell – ''The ''Catalpa'' Adventure – Escape to Freedom'' Cork: The Collins Press, 2010. * Richard Cowan – "Mary Tondut – The Woman in the ''Catalpa'' Story" , Sydney, June 2008 . *

Irish Escape

Documentary produced by the

The ''Catalpa'' rescue was the escape, on 17–19 April 1876, of six Irish

The ''Catalpa'' rescue was the escape, on 17–19 April 1876, of six Irish Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ...

prisoners from the Convict Establishment (now Fremantle Prison

Fremantle Prison, sometimes referred to as Fremantle Gaol or Fremantle Jail, is a former Australian prison and World Heritage Site in Fremantle, Western Australia. The site includes the prison cellblocks, gatehouse, perimeter walls, cottages, ...

), a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer ...

in Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. They were taken on the convict ship

A convict ship was any ship engaged on a voyage to carry convicted felons under sentence of penal transportation from their place of conviction to their place of exile.

Description

A convict ship, as used to convey convicts to the British colo ...

''Hougoumont

Château d'Hougoumont (possibly originally Goumont or Gomont) is a walled manorial compound, situated at the bottom of an escarpment near the Nivelles road in the Braine-l'Alleud municipality, near Waterloo, Belgium. The site served as one o ...

'' to Fremantle, Western Australia

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

, arriving 9 January 1868. In 1869, pardons had been issued to many of the imprisoned Fenians. Another round of pardons was issued in 1871, after which only a small group of "military" Fenians remained in Western Australia's penal system.

In 1874, prisoner James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

* James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Queb ...

secretly sent a letter to New York City journalist John Devoy

John Devoy (, ; 3 September 1842 – 29 September 1928) was an Irish republican Rebellion, rebel and journalist who owned and edited ''The Gaelic American'', a New York weekly newspaper, from 1903 to 1928.

Devoy dedicated over 60 year ...

, who worked to organize a rescue. Using donations collected by Devoy from Irish-Americans, Fremantle escapee John Boyle O'Reilly

John Boyle O'Reilly (; 28 June 1844 – 10 August 1890) was an Irish poet, journalist, author and activist. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australi ...

, then living in Boston, purchased a merchant ship, ''Catalpa'', and sailed her to international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

off Rockingham, Western Australia

Rockingham is a suburb of Perth, Western Australia, located 47 km south-south-west of the city centre. It acts as the primary centre for the City of Rockingham. It has a beachside location at Mangles Bay, the southern extremity of Cockburn ...

. On 17 April 1876 at 8:30 am, Wilson and five other Fenians working outside the prison walls, Thomas Darragh, Martin Hogan, Michael Harrington, Thomas Hassett, and Robert Cranston, boarded a whaleboat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that was used for catching whales, or a boat of similar design that retained the name when used for a different purpose. Some whaleboats were used from whaling ships. Other whaleboats would operate from the s ...

O'Reilly had dispatched, were taken aboard ''Catalpa'', and escaped to New York.

Fenians and plans to escape

Dublin Castle administration

Dublin Castle was the centre of the government of Ireland under English and later British rule. "Dublin Castle" is used metonymically to describe British rule in Ireland. The Castle held only the executive branch of government and the Privy Cou ...

arrested supporters of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

, a secret society

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ag ...

dedicated to Irish independence, and transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln.

It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she ...

62 of them to the British penal colony of Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. They were convicted of crimes ranging from treason-felony to outright rebellion. Sixteen were soldiers who were court-martialled for failing to report or stop the treason and mutinous acts of the others. Among them was John Boyle O'Reilly

John Boyle O'Reilly (; 28 June 1844 – 10 August 1890) was an Irish poet, journalist, author and activist. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australi ...

, later to become the editor of the Boston newspaper ''The Pilot''. They were sent on the convict ship

A convict ship was any ship engaged on a voyage to carry convicted felons under sentence of penal transportation from their place of conviction to their place of exile.

Description

A convict ship, as used to convey convicts to the British colo ...

''Hougoumont

Château d'Hougoumont (possibly originally Goumont or Gomont) is a walled manorial compound, situated at the bottom of an escarpment near the Nivelles road in the Braine-l'Alleud municipality, near Waterloo, Belgium. The site served as one o ...

'', arriving at Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

on 9 January 1868, at the Convict Establishment (now Fremantle Prison

Fremantle Prison, sometimes referred to as Fremantle Gaol or Fremantle Jail, is a former Australian prison and World Heritage Site in Fremantle, Western Australia. The site includes the prison cellblocks, gatehouse, perimeter walls, cottages, ...

).

In 1869, O'Reilly escaped on the whaling ship ''Gazelle'' in Bunbury with assistance of the local Catholic priest, Father Patrick McCabe, and settled in Boston. Soon after his arrival, O'Reilly found work with ''The Pilot'' newspaper and eventually became editor. In 1871, another Fenian, John Devoy

John Devoy (, ; 3 September 1842 – 29 September 1928) was an Irish republican Rebellion, rebel and journalist who owned and edited ''The Gaelic American'', a New York weekly newspaper, from 1903 to 1928.

Devoy dedicated over 60 year ...

, was granted amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

in England on condition that he settle outside Ireland. He sailed to New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and became a newspaperman for the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the '' New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

Hi ...

''. He joined the Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael (CnG) (, ; "family of the Gaels") is an Irish republican organization, founded in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Bro ...

, an organization that supported armed insurrection in Ireland.

In 1869, pardons had been issued to many of the imprisoned Fenians. Another round of pardons were issued in 1871, after which only a small group of "military" Fenians remained in Western Australia's penal system. In 1874, Devoy received a smuggled letter from imprisoned Fenian James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

* James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Queb ...

, who was among those the British had not released.

Dear Friend, remember this is a voice from the tomb. For is not this a living tomb? In the tomb it is only a man's body that is good for worms, but in the living tomb the canker worm of care enters the very soul. Think that we have been nearly nine years in this living tomb since our first arrest and that it is impossible for mind or body to withstand the continual strain that is upon them. One or the other must give way. It is in this sad strait that I now, in the name of my comrades and myself, ask you to aid us in the manner pointed out... We ask you to aid us with your tongue and pen, with your brain and intellect, with your ability and influence, and God will bless your efforts, and we will repay you with all the gratitude of our natures... our faith in you is unbound. We think if you forsake us, then we are friendless indeed. —James WilsonDevoy discussed the matter with O'Reilly and Thomas McCarthy Fennell, and Fennell suggested that a ship be purchased, laden with a legitimate cargo, and sailed to Western Australia, where it would not be expected to arouse suspicion. The Fenian prisoners would then be rescued by stealth rather than force of arms. Devoy approached the 1874 convention of the Clan na Gael and got the Clan to agree to fund a rescue of the men. He then approached

whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales for their products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that was important in the Industrial Revolution. Whaling was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16t ...

agent John T. Richardson, who told them to contact his son-in-law, whaling captain George Smith Anthony, who agreed to help.

''Catalpa''

In 1875, the Clan's committee purchased (in the name of their member James Reynolds) three-masted merchant

In 1875, the Clan's committee purchased (in the name of their member James Reynolds) three-masted merchant bark

Bark may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Arts and entertainment

* ''Bark'' (Jefferson Airplane album), ...

''Catalpa'' for $5,500 ($ in dollars). She measured 202.05 tons and was 90 feet long, 25 feet in breadth and 12.2 feet deep. She had earlier been a whaleship, sailing out of New Bedford, but had been converted to merchant service with an open hold. Under Captain Anthony's direction, ''Catalpa'' was carefully restored to the fitting and rigging of a whaleship "ostensibly for a voyage of eighteen months or two years in the North and South Atlantic". Anthony's recruited crew of twenty-three included a highly qualified first mate, Samuel P. Smith, and a representative of the conspirators, Dennis Duggan, who shipped as a carpenter. The remainder were mostly Kanakas

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and Blackbirding, involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British Empire, British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Queen ...

, Malays and Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

, some with invented names.

Departure and voyage

On 29 April 1875, ''Catalpa'' sailed fromNew Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. At the 2020 census, New Bedford had a population of 101,079, making it the state's ninth-l ...

. At first, most of the crew was unaware of their real mission. Anthony noticed too late that the ship's marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at t ...

was broken, so he had to rely on his personal skills for navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

. They hunted whales in the Atlantic for five months before sailing to Fayal Island

Faial Island (), also known as Fayal Island, is a Portugal, Portuguese island of the Central Group or ''Grupo Central'' of the Azores, in the Atlantic Ocean.

The Capelinhos volcano is the westernmost point of the island and is considered the we ...

in the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

, where they offloaded 210 barrels of sperm whale oil in late October. Unfortunately, much of the crew deserted the ship and they also had to leave behind three sick men. Anthony recruited replacement crew members and set sail for Western Australia on 6 November.

Undercover operatives

To manage the "land end" of the rescue operation, John Devoy signed up Fenian agents John J. Breslin and Thomas Desmond to go to Western Australia. Breslin masqueraded as American businessman "James Collins", with suitableletter of introduction

The letter of introduction, along with the visiting card, was an important part of polite social interaction in the 18th and 19th centuries. It remains important in formal situations, such as an ambassador presenting his or her credentials (a ...

, while Desmond adopted the alias of Johnson. They departed the US in September 1875 and arrived in Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

in November 1875, after which "they separated and became ostensible strangers." Coincidentally, the Irish Republican Brotherhood had sent two of their own agents, Denis MacCarthy and John Walsh, to organise an escape attempt, and a local Fenian named John King was working on his own plan. John Breslin was able to bring all three plans together. Breslin, as Collins, lodged in the Emerald Isle Hotel in Fremantle, while Thomas Desmond took a job as a wheelwright

A wheelwright is a Artisan, craftsman who builds or repairs wooden wheels. The word is the combination of "wheel" and the word "wright" (which comes from the Old English word "''wryhta''", meaning a worker - as also in shipbuilding, shipwright ...

and recruited five local Irishmen who were to cut the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

lines connecting Perth to Albany on the day of escape (there was no link to the eastern colonies of Australia until 1877). Breslin became acquainted with Sir William Cleaver Robinson, the Governor of Western Australia. Robinson took Breslin on a tour of the Convict Establishment (now Fremantle Prison) where he secretly informed the prisoners that an escape was due. While staying at the hotel, Breslin engaged in a love affair with 22-year-old chamber maid, Mary Tondut. She became pregnant and Anthony paid for her to go to Sydney but never saw her again. In December 1876, Tondut gave birth to Breslin's only child, John Joseph Tondut.

Rescue preparations

''Catalpa'' fell behind the intended schedule owing to weather conditions. After 11 months at sea, she dropped anchor off Bunbury on 28 March 1876. Anthony and Breslin met and began to prepare for the rescue. While in Bunbury, Breslin (a.k.a. Collins) stayed in Spencer's Hotel (operated by William Spencer). Anthony and Breslin briefly travelled back together to Fremantle on on 1 April, arriving the next day and were surprised to find theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

gunboat HMS ''Conflict'' in port, necessitating postponement of their plan. Breslin and Anthony travelled to the intended escape departure point in Rockingham. A couple of days later, Anthony and Breslin were invited to a party at the governor's residence. Anthony returned to Bunbury via mail coach on 6 April and discovered that the crew had stowed away another ticket-of-leave convict. Anthony informed the authorities and they took the man ashore. Anthony departed for Rockingham on 15 April.

The escape had been planned for 6 April, but the appearance of ''Conflict'', other Royal Navy ships and customs officers led to a postponement. The escape was rearranged for 17 April, when most of the Convict Establishment garrison was watching the Perth Yacht Club

The escape had been planned for 6 April, but the appearance of ''Conflict'', other Royal Navy ships and customs officers led to a postponement. The escape was rearranged for 17 April, when most of the Convict Establishment garrison was watching the Perth Yacht Club regatta

Boat racing is a sport in which boats, or other types of watercraft, race on water. Boat racing powered by oars is recorded as having occurred in ancient Egypt, and it is likely that people have engaged in races involving boats and other wa ...

.

Escape and pursuit

''Catalpa'' droppedanchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal, used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ', which itself comes from the Greek ().

Anch ...

in international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

off Rockingham and dispatched a whaleboat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that was used for catching whales, or a boat of similar design that retained the name when used for a different purpose. Some whaleboats were used from whaling ships. Other whaleboats would operate from the s ...

to shore. At 8:30 am, six Fenians who were working in work parties outside the prison walls, absconded—Thomas Darragh, Martin Hogan, Michael Harrington, Thomas Hassett, Robert Cranston and James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

* James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Queb ...

. They were met by Breslin and Desmond and picked up in horse traps. According to Anthony, a seventh Fenian, James Kiely, was intentionally left behind because during his trial he had offered to divulge the names of comrades in an effort to obtain a reduced sentence for himself. Kiely, however, claimed that he was unable to get away from his guard. He was released on licence in 1878 and pardoned in 1905. The men raced south to Rockingham pier where Anthony awaited them with the whaleboat. A local named James Bell he had spoken to earlier saw the men and quickly alerted the authorities.

As they rowed to ''Catalpa'', a fierce squall struck, breaking the whaleboat's mast. The storm lasted till dawn on 18 April and was so intense that Anthony later stated that he did not expect the small boat to survive. At 7 am, with the storm over, they again made for ''Catalpa'' but an hour later spotted the screw steamer

A screw steamer or screw steamship (abbreviated "SS") is an old term for a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine, using one or more propellers (also known as ''screws'') to propel it through the water. Such a ship was also known as an " ...

''Georgette

Georgette is a feminine given name, the French form of (''Geōrgia''), the feminine form of George.

Georgette may refer to:

People

* Georgette Barry (1919–2003), stage name Andrea King, American actress

* Georgette Bauerdorf (1924–1944), Am ...

'', which had been commandeered by the colonial governor, making for the whaler. The men lay down in the whaleboat and it was not seen by ''Georgette''. ''Georgette'' found ''Catalpa'' but, in Captain Anthony's absence, the first mate refused to allow the colonial police to board as the ship was outside the colony's three-mile limit

The three-mile limit refers to a traditional and now largely obsolete conception of the international law of the seas which defined a country's territorial waters, for the purposes of trade regulation and exclusivity, as extending as far as the re ...

. The steamer was forced to return to Fremantle for coal after following the ''Catalpa'' for several hours.

As the whaleboat again made for the ship, a police cutter with 30 to 40 armed men was spotted. The two boats raced to reach the ''Catalpa'' first, with the whaleboat winning, and the men climbing aboard as the police cutter passed by. The cutter turned, lingered briefly beside ''Catalpa'', and then headed to shore.

Saved by the US flag

Early on 19 April the refuelled and now armed ''Georgette'' returned and came alongside the whaler, demanding the surrender of the prisoners and attempting to herd the ship back into Australian waters. They fired a warning shot with a 12-pounder (5 kg) cannon that had been installed the night before. Ignoring the demand to surrender, Anthony hoisted and pointed towards theU.S. flag

The national flag of the United States, often referred to as the American flag or the U.S. flag, consists of thirteen horizontal stripes, alternating red and white, with a blue rectangle in the canton bearing fifty small, white, five-point ...

, warning that an attack on ''Catalpa'' would be considered an act of war against the U.S., and proceeded westward. This was well recognised by Captain O'Grady of ''Georgette'', who had sailed out of New York, was friendly toward Anthony and had, on 1 April, unwittingly entertained him in the steamer's pilot house, closely briefing him on the coast between Fremantle and Rockingham.

Governor Robinson had ordered the police on ''Georgette'' not to create an incident outside territorial waters. After steaming around threateningly for about an hour, ''Georgette'' headed back to Fremantle and ''Catalpa'' slipped away into the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

.

Aftermath

''Catalpa'' did her best to avoid the Royal Navy on her way back to the U.S. O'Reilly received the news of the escape on 6 June and released the news to the press. The news sparked celebrations in the United States and Ireland and anger in Britain and Australia (although there was also sympathy for the cause within the Australian population). ''Catalpa'' returned to New York on 19 August 1876. On the other hand, it did not cause any diplomatic issues between the U.S. and the U.K., and the governor of Western Australia was glad to that the Fenians had "become the problem of some other nation". On 1 December 1876, seven months after the escape, ''Georgette'' sank nearBusselton

Busselton is a city in the South West (Western Australia), South West region of the States and territories of Australia, state of Western Australia approximately south-west of Perth. Busselton has a long history as a popular holiday destin ...

.

George Smith Anthony remained in New Bedford with his wife and children, never returning to sea. He was appointed New Bedford Port Inspector in 1886. With the help of a journalist, Z. W. Pease, he published an account of his journey, '' The ''Catalpa'' Expedition'', in 1897. He died in 1913.

Thomas Desmond went on to become Sheriff of San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

from 1880 to 1881

John Breslin returned as a hero. He continued contact with the Clan na Gael and Devoy, and died in 1887.

''Catalpa'' was presented to Captain Anthony, John Richardson and Henry Hathaway in lieu of payment. She was eventually sold and turned into a coal barge. Not of great value in this capacity, ''Catalpa'' was finally condemned at the port of Belize

Belize is a country on the north-eastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a maritime boundary with Honduras to the southeast. P ...

, British Honduras

British Honduras was a Crown colony on the east coast of Central America — specifically located on the southern edge of the Yucatan Peninsula from 1783 to 1964, then a self-governing colony — renamed Belize from June 1973

.

Mythologising

The story of ''Catalpa'' escape grew more dramatic in each retelling. After the first mate declined to allow the police to board the ship, he wrote in the ship's log:At 8 Am the Steam Ship ''Georgette'' hailed me and her captian asked me if I had seen a boat with a lot of men in it—I told him no. Another man asked me if the Captian was on board—I told him no. Asked if I had any strangers on board—I told him no. Then asked if he might come on board—I told him no. The steamer then left me and I stood on my course.In the version of the tale told by Anthony (who was not a witness), it became:

The captain of the English steamer asked where the boat was which was missing from the cranes... "I don't know anything about it," said Mr. Smith. "Can I come aboard?" asked the officer. "Not by a damned sight," was Mr. Smith's reply.In ''The Emerald Whaler'' (1960) by William Laubenstein, a fictionalised version, the encounter became much more confrontational:

This is Her Majesty's ship of war ''Georgette''... "Hell of a lookin' warship," Sam jibed. "What's yer guns?" ... "What is your business?" ... "I'm on th' high seas, as any fool can see," Sam countered ... "Your larboard boat is missing" ... "Captain has it" ... "I am going to board your ship!" ... "Like hell you are! You try it an' you'll be goddamned good and sorry! ... What the hell did we lick the pants offn' you damn Britishers in 1812 about? ... You don't own the goddamn ocean!"In addition, over the years, ''Georgette'' was presented as bigger and larger than it actually was: roughly the same size as ''Catalpa'', and outfitted with a single cannon. In

Thomas Keneally

Thomas Michael Keneally, Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and actor. He is best known for his historical fiction novel ''Schindler's Ark'', the story of Oskar Schindler' ...

's ''The Great Shame and the Triumph of the Irish in the English-Speaking World'' (1999), she is described as the Royal Navy's newest ship and being twice the size of ''Catalpa''.

Memorials

On 9 September 2005 a memorial was unveiled in Rockingham to commemorate the escape. The memorial, a large statue of six wild

On 9 September 2005 a memorial was unveiled in Rockingham to commemorate the escape. The memorial, a large statue of six wild geese

A goose (: geese) is a bird of any of several waterfowl species in the family Anatidae. This group comprises the genera '' Anser'' (grey geese and white geese) and ''Branta'' (black geese). Some members of the Tadorninae subfamily (e.g., Egyp ...

, was created by Western Australian artists Charlie Smith and Joan Walsh Smith. The geese refer to the phrase "The Wild Geese

''The Wild Geese'' is a 1978 war film starring an ensemble cast led by Richard Burton, Roger Moore, Richard Harris and Hardy Krüger. The film, which was directed by Andrew V. McLaglen, was the result of a long-held ambition of producer Eua ...

" which was a name given to Irish soldiers who served in European armies after being exiled from Ireland. The Fenians transported to Western Australia adopted the phrase for themselves during their voyage on board ''Hougoumont

Château d'Hougoumont (possibly originally Goumont or Gomont) is a walled manorial compound, situated at the bottom of an escarpment near the Nivelles road in the Braine-l'Alleud municipality, near Waterloo, Belgium. The site served as one o ...

'', even publishing a shipboard newspaper entitled '' The Wild Goose''.

In 1976 a memorial stone was erected in New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. At the 2020 census, New Bedford had a population of 101,079, making it the state's ninth-l ...

, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the rescue. New Bedford was the home port of ''Catalpa''.

Exhibition

From 22 September 2006 to 3 December 2006 anexhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibiti ...

, called "Escape: Fremantle to Freedom," opened at Fremantle Prison displaying many artefacts relating to the ''Catalpa'' rescue. The exhibition received over 20,000 visitors.

James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

* James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Queb ...

(1836–1921)

File:MichaelHarrington.jpg, Michael Harrington

Edward Michael Harrington Jr. (February 24, 1928 – July 31, 1989) was an American democratic socialist. As a writer, he was best known as the author of '' The Other America'' (1962). Harrington was also a political activist, theorist, profess ...

(1825–1886)

File:Thomas Darragh.jpg, Thomas Darragh (1834–1912)

File:RobertCranstonConvict.jpg, Robert Cranston (1842–1914)

File:John Boyle O'Reilly.jpg, John Boyle O'Reilly

John Boyle O'Reilly (; 28 June 1844 – 10 August 1890) was an Irish poet, journalist, author and activist. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australi ...

(1844–1890)

In popular culture

* Musician and local historian Brendan Woods authored a theatrical production about the breakout titled ''The Catalpa'' directed by Gerry Atkinson with a cast of 22. On 15 November 2006 ''The Catalpa'' premiered at the Fremantle Town Hall and ran until 25 November. Theplay

Play most commonly refers to:

* Play (activity), an activity done for enjoyment

* Play (theatre), a work of drama

Play may refer also to:

Computers and technology

* Google Play, a digital content service

* Play Framework, a Java framework

* P ...

was based on the diaries of Denis Cashman, with the poetry of John Boyle O'Reilly

John Boyle O'Reilly (; 28 June 1844 – 10 August 1890) was an Irish poet, journalist, author and activist. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australi ...

set to music and dance supported by a five-part Musical ensemble

A musical ensemble, also known as a music group, musical group, or a band is a group of people who perform Instrumental music, instrumental and/or vocal music, with the ensemble typically known by a distinct name. Some music ensembles consist ...

. The show sold out on three of its four night run.

* Irish rebel music band The Wolfe Tones

The Wolfe Tones are an Irish rebel music band that incorporate Irish traditional music in their songs. Formed in 1963, they take their name from Theobald Wolfe Tone, one of the leaders of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, with the double meaning ...

recorded a song about the Catalpa incident called ''The Fenians' Escape''.

* The Real McKenzies

The Real McKenzies is a Canadian Celtic punk band founded in 1992 and based in Vancouver, British Columbia. They are considered the founders of the Canadian Celtic punk movement, and were one of the first Celtic punk bands, albeit 10 years af ...

, a Celtic punk band from British Columbia, Canada, included their rendition of the song "The Catalpa" on the 2005 Fat Wreck Chords album " 10,000 Shots".

* Donal O'Kelly's one man play ''Catalpa'' was an international success, winning a Scotsman Fringe First Award at the 1996 Edinburgh Festival Fringe

The Edinburgh Festival Fringe (also referred to as the Edinburgh Fringe, the Fringe or the Edinburgh Fringe Festival) is the world's largest performance arts festival, which in 2024 spanned 25 days, sold more than 2.6 million tickets and featur ...

and the Critic's Prize at the Melbourne International Festival in 1997.

* Western Australian folk music band, The Settlers released the album ''Bound For Western Australia'' in 1978 that included the song ''The Catalpa''

* Australian folk band, The Bushwackers featured the song ''The Catalpa'' on the album ''Beneath the Southern Cross''.

* An Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is Australia’s principal public service broadcaster. It is funded primarily by grants from the federal government and is administered by a government-appointed board of directors. The ABC is ...

production, ''The Catalpa Rescue'', was shown on ABC Television on 25 October 2007.

* Fenian Park, Catalpa Park and O'Reilly Park, in Glen Iris, Bunbury.

* In 2021 a new GAA

Gaa may refer to:

* Gaa language, a language of Nigeria

* gaa, the ISO 639 code for the Ga language of Ghana

GAA may stand for:

Compounds

* Glacial (water-free), acetic acid

* Acid alpha-glucosidase, also known as glucosidase, alpha; acid, an e ...

team was founded in the Rockingham Area to compete in the GAAWA competitions called Na Fianna Catalpa

See also

*Cyprus mutiny

The ''Cyprus'' mutiny took place on 14 August 1829 in Recherche Bay off the British Van Diemen's Land#Penal colony, penal settlement of Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania, Australia). Convicts in Australia, Convicts seized the brig and sailed her t ...

* Frederick escape

The ''Frederick'' escape was an 1834 incident in which the brig ''Frederick'' was hijacked by ten Australian convicts and used to abscond to Chile, where they lived freely for two years. Four of the convicts were later recaptured and returned t ...

References

Further reading

* John Devoy – John Devoy's ''Catalpa'' Expedition () * John Devoy – Recollections of an Irish Rebel * Laubenstein, William J – "The Emerald Whaler" London : Deutsch, 1961. * Seán O'Luing – "Fremantle Mission" *View the Memorial Launch Video

*Vincent McDonnell – ''The ''Catalpa'' Adventure – Escape to Freedom'' Cork: The Collins Press, 2010. * Richard Cowan – "Mary Tondut – The Woman in the ''Catalpa'' Story" , Sydney, June 2008 . *

Video and media

Irish Escape

Documentary produced by the

PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

Series Secrets of the Dead

''Secrets of the Dead'', produced by WNET 13 New York, is an ongoing PBS television series which began in 2000. The show generally follows an investigator or team of investigators exploring what modern science can tell viewers about some of t ...

{{IRB

1876 in Australia

Convictism in Western Australia

Irish Republican Brotherhood

Rockingham, Western Australia

Escapees from British detention

Australian folklore

Whaling ships

April 1876

Gilded Age

Maritime folklore