Account of caste system in 1885

In 1885, during his visit to Malé, C.W. Rosset observed that the beds in the region were made of different materials based on caste. The higher castes used brass chains, the middle castes used iron chains, while the lower castes used coiled ropes to suspend the beds. The beddings of different castes in Malé vary in materials and quality. The higher castes used red silk for their mattresses and pillows, the middle castes use cotton sheets, while the lower castes sleep on straw. Additionally, the mat used to cover the straw mattress was designed with patterns and quality that are determined by the caste of the owner. C.W. Rosset mentions that several times when he visited the lower caste homes, the women of the home would participate in the conversation while always remaining invisible in their home. C.W. Rosset mentions in his journal during his visit in 1885 that the lower caste formed 60 percent of the Maldives population. Caste divisions were strictly upheld inAbolishment of caste system in 1968

This caste system was eliminated after the founding of the republic in 1968; as of now, just a few of its remnants remain.Segregation of caste

Occupational segregation in Maldives where the island of a given craft was isolated to others, is distinctive proof of the persistence of caste. The craftsmen like the weavers, goldsmiths, locksmiths, blacksmiths, mat-weavers, potters, turners, and the carpenters and others, are all situated in different islands. In other words, their craftsmen do not mix; each craft has its own island. And people have also adhered to this rule. Men of the jeweler caste and trade live in the islands of Rinbudhoo,Surname and name structure

Three parts make up the traditional Maldivian name, as examples Maakana Kudatuttu Didi or Dhoondeyri Ali Manikfan.

The surname was the first element, and the given name—or a word of affection like Tuttu, Kuda, or Don—or a combination of a term and a given name, as Kuda Hussain or Don Mariyambu—was the second element.

The third component, which was optional, signified status and/or cognomen via affiliation or birth.

Traditional birth ranks and cognomen included Manippulu, Goma, Kalaa, Kambaa, Rahaa, Manikfan, Didi, Seedi, Sitti, Maniku, Manike, Thakurufan, Thakuru, Kalo, Soru, Manje, and others.

The family surname was primarily patrilinearly transmitted. However, matrilinear transfer of surnames was not unusual. Which parent had a better social and economical situation determined this. The historically materialistic Maldivians would have given the children their mother's last name if the mother had more material possessions and better connections than the father.

Three parts make up the traditional Maldivian name, as examples Maakana Kudatuttu Didi or Dhoondeyri Ali Manikfan.

The surname was the first element, and the given name—or a word of affection like Tuttu, Kuda, or Don—or a combination of a term and a given name, as Kuda Hussain or Don Mariyambu—was the second element.

The third component, which was optional, signified status and/or cognomen via affiliation or birth.

Traditional birth ranks and cognomen included Manippulu, Goma, Kalaa, Kambaa, Rahaa, Manikfan, Didi, Seedi, Sitti, Maniku, Manike, Thakurufan, Thakuru, Kalo, Soru, Manje, and others.

The family surname was primarily patrilinearly transmitted. However, matrilinear transfer of surnames was not unusual. Which parent had a better social and economical situation determined this. The historically materialistic Maldivians would have given the children their mother's last name if the mother had more material possessions and better connections than the father.

Name inheritance

In the service of kings and nobles, slaves were frequently promoted to important positions. Sometimes, the given names of their slave ancestors were adopted as surnames by their descendants. For instance, a family by the name of Yaagoot descended from a slave by the same name who worked as a slave for a Diyamigili sultan in the eighteenth century. An African Negro slave by the name of Heyna who belonged to Sultan Mohamed Imaduddine IV in the nineteenth century was the ancestor of a family by that name.Offices and titles

Offices were more practical than titles and were not given to holders for life. The held the highest positions.The majority of the titles and positions shared names, with the only distinction being the removal of the suffix (). Faarhanaa, Rannabandeyri, Dorhimeyna, Faamuladeyri, Maafaiy, and Handeygiri or Handeygirin were among the offices. One of the was usually the prime minister (Bodu Vizier). However, there have been several instances of prime ministers who were either or had no other positions. The Faarhanaa, the Rannabandeyri, or the Handeygirin would have been the most likely candidates for prime minister among the . Usually, the Dorhimeyna served as the military's commander-in-chief.

Vazirs

The , or ministers, were ranked below the in the sultans' and sultanas' courts. The line separating the ministers from the sometimes blurred in subsequent years. The terms and ministers were frequently used interchangeably, with replacing the term in ordinary speech. The chief admiral and foreign minister was the Velaanaa (or Velaanaa-Shahbandar), the minister of public works was the Hakuraa, the chief treasurer was the Bodubandeyri, the chief of palace staff was the Maabandeyri, who was in charge of maintaining the royal seal known as the Kattiri Mudi, and the commander of the land forces was the Daharaa (or Daharada).Division heads

Below the ministers, there were a number of smaller positions, such as the Meerubahuru, who oversaw immigration and the port ofChief justice

The Uttama Fandiyaaru, or chief justice, had authority over the . The chief justice was in charge of ecclesiastical and civil justice, as well as the maintenance of mosques, cemeteries, charity trusts, religious rites, and the approval of marriage and divorce. He was also in charge of keeping the Tarikh, the official history book. The Bandaara Naibu, or the Attorney General, and the Chief Justice, shared responsibilities for criminal justice.Governors

The , or regional governors, acted as the sultan or sultana in the distant provinces ("atolls"). In the Maldive language, from which the word atoll () has been borrowed, atoll () refers to a province rather than a coral reef enclosing a lagoon. Atoll's English counterpart in the Maldives is . The , who was (and is now) the principal temporal and spiritual authority, served as the sultan or sultana's representative on each particular populated island or settlement. For the benefit of the or chief treasurer, the and the administered criminal justice and gathered the (poll tax) and (land tax). In Malé, the of Henveyru, Maafannu, Macchangoli, and Galollu had the temporal responsibilities of the regional as well as the 's tasks. In Malé, the were in charge of maintaining public lands, maintaining law and order, and administering criminal justice. Malé's were solely religious officials.Gazi

Every island had a (now known asKilege

The was the highest honor bestowed by the Maldives' sultans and sultanas. The following titles have been bestowed throughout the previous four to five centuries of the monarchy: Ras Kilege, to both men and women. All of the following are solely available to men: Faarhanaa Kilege, Rannabandeyri Kilege, Dorhimeyna Kilege, Faamuladeyri Kilege, Maafaiy Kilege, Kaulannaa Kilege, Oliginaa Kilege, Daharada Kilege, Kuda Rannabandeyri Kilege, and Kuda Dorhimeyna Kilege. Only Rani Kilege, Maavaa Kilege, Kambaadi Kilege, and Maanayaa Kilege were given to women. Over the past several hundred years, the term has acquired the optional and honorific suffix "". The king-sultan or the queen-sultana were the ex-officio Ras Kilege. The other , who were also referred to as amirs or commanders of the realm, should not be confused with (or ), which is either a term of low status or an honorary method of addressing or referring to holy individuals. A person and his or her immediate family are promoted to the aristocracy when they are given the title of , which were no inherited titles, though.Kangathi

The term "" was a lesser title. These were frequently given to well-known regional figures or occasionally to Malé's middle class. In contrast to the nobles, the awardees were not recognized as aristocrats. ''Maafahaiy, Meyna, Ranahamaanthi, Gadahamaanthi, Hirihamaanthi, Fenna, Wathabandeyri, Kaannaa, Daannaa, and Fandiaiy'' were some of the titles. No instance of a woman receiving a title has been documented.Ranks

The names of the title-holders and officials, from the down to the and , were prefixed to their given names. In normal use, this would have been prefixed with a cognomen designating status by birth; this practice was presumably carried over from the pre-Islamic civilizations' caste systems. These cognomen might have included everything from: The names of their offices would have been prefixed with Manikfan for Seedis, children and grandchildren of , members of previous royal dynasties, and Thakurufan or Takkhan for middle-class individuals, and Kaleyfan or Kaleyge for lower-class individuals. For instance, if a chief judge named Ibrahim had been born into the upper class, he would have gone by the names Ibrahim Uttama Fandiyaaru Manikfan and Ibrahim Uttama Fandiyaaru Kaleygefan. Regardless of his place of origin, he would have been addressed as Ibrahim Uttama Fandiyaaru, or the Subject Chief Justice Ibrahim, in all royal warrants, writs, and ceremonies. The were the exceptions to this rule; their names were solely prefixed with their , regardless of status at birth. The recipient and his or her family were raised to the ranks of the aristocracy by the title, which transcended any status attained by birth.Royals

Members of the royal family had their names prefixed with Manippulu if they were princes, and Goma if they were princesses, or more frequently with nickname like Tuttu, Don, Titti, or Dorhy. The term "" was a new term. Princes and princesses were both referred to as until the early eighteenth century. A prince was really called Kalaa, while a princess was called Kambaa. The royal (patrilinear) line of the governing family did not hold any public office until in recent times of monarchy.Slaves

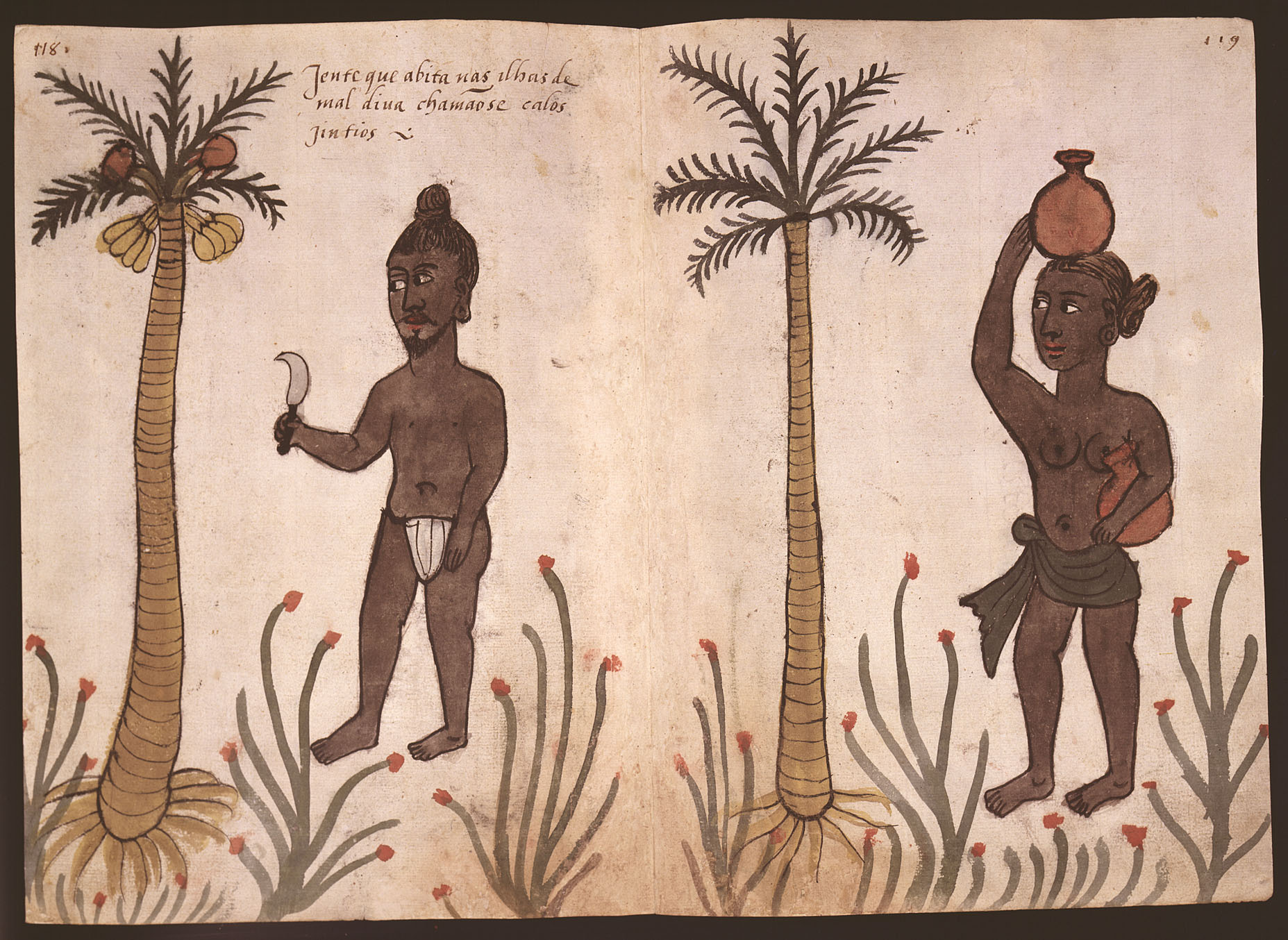

Slaves made up a large portion of the Maldivian population by the 14th century, when one of the oldest accounts of the islands, recorded by the renowned Arab travelerBaburu slaves

Slaves of African origin were called , which meant

Slaves of African origin were called , which meant Charukeysi slaves

: ''SeeLocal slaves

During the Middle Ages, several aristocratic families used local commoners as slaves and occasionally even sold them. During the rule of Sultan Mohamed Ibn Al-Hajj Ali Thukkalaa (r. 1692 – 1701), the situation changed.Fulhû

Fulhu was a rank by affiliation. The name suggested ownership by a person of noble birth. In other words, Ahmed ''Fulhu'' as an example would be either a slave, a slave's ancestor, or a servant of the royal family. Fulhu was the title given to those of the lowest status who joined the royal household for work or foreign slaves purchased by the great nobles and brought back to the Maldives from the slave markets of Arabia. Africans generally made up these slaves.Low caste

Giraavaru people

The most notable remnants of the old caste system may be seen among the few groups at the bottom of the social order. Giravarus is one such group. Giraavaru people were compelled to leave their island in 1968. They were moved over to Male and housed in a few blocks on reclaimed grounds in the Maafanu neighborhood. They were assimilated with other social groups in Male'.Raaverin

Working primarily as Raaverins, or keepers of coconut plantations, the slaves were eventually absorbed by several social groups or castes, most notably the Raaveri.Low caste names

Names with suffix Kalo and Fulhu would be of lower class and would not have been welcomed in the presence of the monarch and nobility unless they were either servants or officials. It is unlikely that a person with name suffix Kalo would have ever been permitted to enter the presence of royalty. A name with suffix Maniku was lower middle class unless they inherited the name from upperclass.Upper caste

The complex social elite structure and the existence of the hereditary nobility are distinctive aspects of Maldivian society that also represent the remnants of a former caste system. Despite being only fully visible in the capital, where the Sultan lived, the aristocracy was present in the southern Maldives.Upper caste names

If the bearers of names with suffix Seedi and Didi were married to royalty or Kilege nobles, or if they were Kilege nobles or descended from them, then their names may have been considered to be of a higher social class. Otherwise those with such names were upper middle class. Names with suffix Didi or Manikufanu in the southern provinces were of nobilityReferences

{{Reflist Further reading The voyage of Francois Pyrard

The voyage of Francois Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas and Brazil, v.1

Traces of castes and other social strata in the Maldives

a case study of social stratification in a diachronic perspective.

Maldives: Ancient Titles, Offices, Ranks and Surnames

Maldives Royal Family