Carl Graham Fisher on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carl Graham Fisher (January 12, 1874 – July 15, 1939) was an American

Harper's Archives

Accessed August 5, 2010. Though he did not invent the name Miami Beach, he popularized it. He platted the second plat in Miami Beach, following the Lummus Brothers. Fisher continued his wise investment in infrastructure. The Although a dedicated enthusiast of automobile travel, Fisher was aware that wealthy vacationers in those days often preferred to cross the long distances to southeastern Florida by

Although a dedicated enthusiast of automobile travel, Fisher was aware that wealthy vacationers in those days often preferred to cross the long distances to southeastern Florida by

In 1925, Fisher's wealth was estimated as exceeding $50 million. In later years, he borrowed heavily and the hurricane in September 1926 damaged a large part of Miami Beach and reduced tourism. The losses in his real-estate ventures and the crash of 1929 left Fisher virtually penniless. "Fisher's financial house of cards began to collapse", according to a

In 1925, Fisher's wealth was estimated as exceeding $50 million. In later years, he borrowed heavily and the hurricane in September 1926 damaged a large part of Miami Beach and reduced tourism. The losses in his real-estate ventures and the crash of 1929 left Fisher virtually penniless. "Fisher's financial house of cards began to collapse", according to a

at the

Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925

' New York: Bonanza Books, 1950. *Fisher, Jane. ''Fabulous Hoosier'' New York, New York: R. M. McBride and Co., 1947 *Fisher, Jerry M. ''The Pacesetter: The Untold Story of Carl G. Fisher'' Ft. Bragg, California: Lost Coast Press, 1998

Castles in the Sand: The Life and Times of Carl Graham Fisher

'. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2000. *Lummus, J. N

''The Miracle of Miami Beach''

(Self published; Miami, Florida), 1944 * Nolan, David.

Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida

'. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984.

Lincoln Highway Association

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fisher, Carl G. 1874 births 1939 deaths American automotive pioneers American segregationists Antisemitism in Florida Businesspeople from Indianapolis Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery People from Montauk, New York People from Greensburg, Indiana People from Miami Beach, Florida White nationalism in Florida

entrepreneur

Entrepreneurship is the creation or extraction of economic value in ways that generally entail beyond the minimal amount of risk (assumed by a traditional business), and potentially involving values besides simply economic ones.

An entreprene ...

in the automotive industry, highway construction and real estate development.

Early life

Carl G. Fisher was born in Greensburg on January 12, 1874. In his early life in Indiana, with family financial strains and a disability, Fisher became a bicycle enthusiast and opened a modest bicycle shop with his brothers. He became involved in bicycle racing, and many activities related to the emerging American auto industry. In 1904, he and friend James A. Allison bought an interest in the U.S.patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

to manufacture acetylene

Acetylene (Chemical nomenclature, systematic name: ethyne) is a chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is u ...

headlight

A headlamp is a lamp attached to the front of a vehicle to illuminate the road ahead. Headlamps are also often called headlights, but in the most precise usage, ''headlamp'' is the term for the device itself and ''headlight'' is the term for t ...

s, a precursor to electric models that became common about ten years later. Soon, his firm supplied nearly every headlamp used on automobiles in the United States as manufacturing plants were built all over the country to supply the demand. The headlight patent made him rich as an automotive part

Part, parts or PART may refer to:

People

*Part (surname)

*Parts (surname)

Arts, entertainment, and media

*Part (music), a single strand or melody or harmony of music within a larger ensemble or a polyphonic musical composition

*Part (bibliograph ...

s supplier when Allison and he sold their company, Prest-O-Lite, to Union Carbide in 1913 for $9 million (equivalent to $268 million in 2022).

Fisher operated in Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

what is believed to be the first automobile dealership in the United States, and also worked at developing an automobile racetrack locally. After being injured in stunts himself, and following a safety debacle at the new Indianapolis Motor Speedway

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway is a motor racing circuit located in Speedway, Indiana, United States, an enclave suburb of Indianapolis, Indiana. It is the home of the Indianapolis 500 and the Brickyard 400, and and formerly the home of the U ...

, of which he was a principal, he helped develop paved racetracks and public roadways. Improvements he implemented at the speedway led to its nickname, "The Brickyard."

In 1912, Fisher conceived and helped develop the Lincoln Highway

The Lincoln Highway is one of the first transcontinental highways in the United States and one of the first highways designed expressly for automobiles. Conceived in 1912 by Indiana entrepreneur Carl G. Fisher, and formally dedicated Octob ...

, the first road for the automobile across the entire United States. A convoy trip a few years later by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

along Fisher's Lincoln Highway was a major influence upon then-Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

years later in championing the Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Hi ...

during his presidency in the 1950s.

Following on the success of his east-west Lincoln Highway, Fisher initiated efforts on the north-south Dixie Highway

Dixie Highway was a United States auto trail first planned in 1914 to connect the Midwest with the South. It was part of a system and was expanded from an earlier Miami to Montreal highway. The final system is better understood as a network o ...

in 1914, which led from Michigan to Miami. Under his leadership, the initial portion was completed within a single year, and he led an automobile caravan to Florida from Indiana.

At the south end of the Dixie Highway in Miami, Florida, Fisher saw another opportunity. Fisher, with the assistance of his partners John Graham McKay and Thomas Walkling, became involved in the real-estate development of a largely unpopulated barrier island near Miami. They invested in land and dredging, promoted deed restrictions, and provided much-needed working capital to the earlier Lummus and Collins family pioneers to develop Miami Beach

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. It is part of the Miami metropolitan area of South Florida. The municipality is located on natural and human-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean an ...

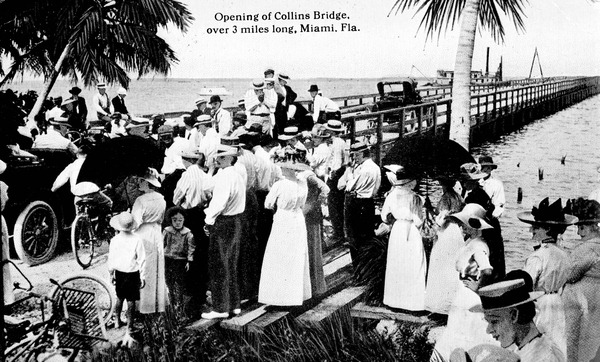

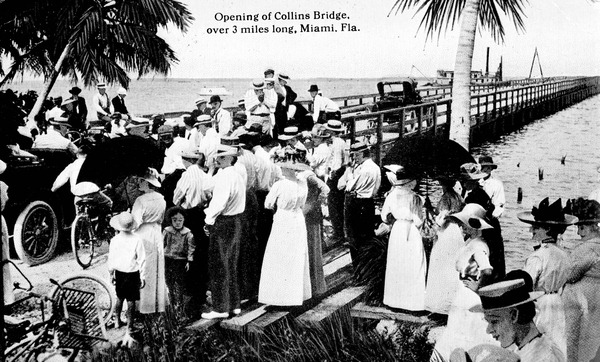

. For example, Fisher funded completion on the first bridge to link Miami to Miami Beach. The new Collins Bridge crossed Biscayne Bay directly at the terminus of the Dixie Highway. Cars were charged a toll to cross.

Fisher is one of the best-known promoters of the Florida land boom of the 1920s, which inculcated racial deed restrictions into Florida culture for decades. Prior to the hurricane in September 1926, he was worth an estimated $50-100 million depending on the source. This unforeseen storm reduced Miami Beach to rubble. Fisher's financial endeavors never fully recovered.

His next major project, Montauk, was envisioned as the "Miami Beach of the North." It was to be located at on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. It was cut short by Fisher's losses in the Florida land-boom bust, the Great Depression of 1929, his divorce, and alcoholism.

After his fortune was lost, he lived in a small cottage in Miami Beach, doing minor work for old friends. He took on one more project, the Caribbean Club on Key Largo, intended as a "poor man's retreat." He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame

The Automotive Hall of Fame is a hall of fame and museum honoring influential figures in the history of the automotive industry. Located in Dearborn, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, US. The Hall of Fame is part of the MotorCities National Herita ...

in 1971. Just south of Miami Beach, Fisher Island is named for him and is one of the wealthiest and most exclusive residential areas in the United States. It is built on a parcel that is a combination of "the old Vanderbilt estate" bought from Fisher and a municipal trash dump.

Private life

Carl Fisher was born in Greensburg, Indiana, nine years after the end of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, the son of Albert H. and Ida Graham Fisher. Apparently suffering from alcoholism

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World He ...

, a problem which also plagued Carl later in life, his father left the family when he was a child. Severely astigmatic, he had difficulty paying attention in school, as uncorrected astigmatism can cause headaches, eyestrain, and blurred vision at all distances. He quit school when he was 12 years old to help support his family.

For the next five years, Fisher held a number of jobs. He worked in a grocery and a bookstore, then later he sold newspapers, books, tobacco, candy, and other items on trains departing Indianapolis, a major railroad center not far from Greensburg. He opened a bicycle repair shop in 1891 with his two brothers. A successful entrepreneur

Entrepreneurship is the creation or extraction of economic value in ways that generally entail beyond the minimal amount of risk (assumed by a traditional business), and potentially involving values besides simply economic ones.

An entreprene ...

, he expanded his business and became involved in bicycle racing

Cycle sport is competitive physical activity using bicycles. There are several categories of bicycle racing including road bicycle racing, cyclo-cross, mountain bike racing, track cycling, BMX, and cycle speedway. Non-racing cycling spo ...

and later, automobile racing

Auto racing (also known as car racing, motor racing, or automobile racing) is a motorsport involving the racing of automobiles for competition. In North America, the term is commonly used to describe all forms of automobile sport including non ...

. During his many promotional stunts, he was frequently injured on the dirt and gravel roadways, leading him to become one of the early developers of automotive safety features. A highly publicized stunt involved dropping a bicycle from the roof of the tallest building in Indianapolis, which brought on a confrontation with the police.

In 1909, while 35 and engaged to his fiancée, Fisher met and married 15-year-old Jane Watts. His ex-fiancée sued him for a breach of promise

Breach of promise is a common-law tort, abolished in many jurisdictions. It was also called breach of contract to marry,N.Y. Civil Rights Act article 8, §§ 80-A to 84. and the remedy awarded was known as heart balm.

From at least the Middle ...

. Meanwhile, he and his new wife Jane went on a business trip for their honeymoon. In 1921, they had one child, who died a month later from pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis is a narrowing of the opening from the stomach to the first part of the small intestine (the pylorus). Symptoms include projectile vomiting without the presence of bile. This most often occurs after the baby is fed. The typical a ...

. She adopted a four-year-old child in 1925; he disapproved and they divorced in Paris in 1926. She then married and divorced three men; after her last marriage she went to court to change her name to Jane Watts Fisher and falsely styled herself as his widow.

Fisher's second marriage, to his secretary, Margaret Eleanor Collier, lasted until his death. She then married Howard W. Lyon, his business associate.

Automobile businesses

In 1904, Fisher was approached by the owner of a U.S. patent to manufacture acetylene headlights. Fisher's firm soon supplied nearly every headlamp used on automobiles in the United States, as manufacturing plants were built all over the country to supply the demand. The headlight patent made him rich as an automotivepart

Part, parts or PART may refer to:

People

*Part (surname)

*Parts (surname)

Arts, entertainment, and media

*Part (music), a single strand or melody or harmony of music within a larger ensemble or a polyphonic musical composition

*Part (bibliograph ...

s supplier and led to friendships with notable auto magnates. Fisher made millions when partner James A. Allison and he sold their Prest-O-Lite

Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) is an American chemical company headquartered in Seadrift, Texas. It has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Dow Chemical Company since 2001. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more fu ...

automobile headlamp business to Union Carbide

Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) is an American chemical company headquartered in Seadrift, Texas. It has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Dow Chemical Company since 2001. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more f ...

.

Fisher also entered the business of selling automobiles, with his friend Barney Oldfield

Berna Eli "Barney" Oldfield (January 29, 1878 – October 4, 1946) was a pioneer American racing driver. His name was "synonymous with speed in the first two decades of the 20th century". He was the winner of the inaugural List of American ope ...

. The Fisher Automobile Company in Indianapolis is considered most likely the first automobile dealership in the United States. It carried multiple models of Oldsmobile

Oldsmobile (formally the Oldsmobile Division of General Motors) was a brand of American automobiles, produced for most of its existence by General Motors. Originally established as "Olds Motor Vehicle Company" by Ransom E. Olds in 1897, it produc ...

, REO, Packard

Packard (formerly the Packard Motor Car Company) was an American luxury automobile company located in Detroit, Michigan. The first Packard automobiles were produced in 1899, and the last Packards were built in South Bend, Indiana, in 1958.

One ...

, Stoddard-Dayton, Stutz

The Stutz Motor Car Company was an American automobile Automotive industry, manufacturer based in Indianapolis, Indiana that produced high-end Sports cars, sports and Luxury vehicle, luxury cars. The company was founded in 1911 as the Idea ...

, and others. Fisher staged an elaborate publicity stunt in which he attached a hot-air balloon to a white Stoddard-Dayton automobile and flew the car over downtown Indianapolis. Thousands of people observed the spectacle and Fisher triumphantly drove back into town, becoming an instant media sensation. Unbeknownst to the public, the flying car had had its engine removed to lighten the load, and several identical cars were driven out to meet it, to allow Fisher to drive back into the city. Afterward, he advertised, "The Stoddard-Dayton was the first automobile to fly over Indianapolis. It should be your first automobile, too." Another stunt involved pushing a car off the roof of a building and then driving it away, to demonstrate its durability.

Indianapolis estate

"Blossom Heath" was Fisher's estate in Indianapolis. Completed in 1913, it was built on Cold Spring Road between the estates of his two friends and Indianapolis Motor Speedway partners, James A. Allison and Frank H. Wheeler. The house included portions of an earlier house on the site and featured a 60-foot-long living room with a 6-foot-wide fireplace where logs burned all day. The house had twelve bedrooms and a huge glass-enclosed sun porch. Fisher built a house for his mother on the southern part of the estate. The estate also included a five-car garage, an indoor swimming pool, a polo course, a stable, an indoor tennis court and gymnasium, a greenhouse, and extensive gardens. A newspaper article dated February 2, 1913, described the simple dignity of the house. Unlike some of his friends and neighbors, Fisher built a large but simple house decorated primarily in yellow, his favorite color. It did not contain exotic woodwork, elaborate carvings, or extensive decoration. In 1928, after Fisher moved permanently to Miami Beach, the Fisher estate in Indianapolis was leased and later purchased by the Park School for Boys. The Fisher mansion was damaged by fire in the 1950s and the rear portion of the house was demolished and replaced with a classroom wing during 1956–57. The property was sold to Marian College in the 1960s and combined with two nearby estates into one campus. Today, none of Fisher's original buildings remain on the Marian College campus.

Auto racing

In 1909, Fisher joined a group of Indianapolis businessmen in a new project. Arthur C. Newby (president ofNational

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

), Frank H. Wheeler (maker of the Wheeler-Schebler carburetor

A carburetor (also spelled carburettor or carburetter)

is a device used by a gasoline internal combustion engine to control and mix air and fuel entering the engine. The primary method of adding fuel to the intake air is through the Ventu ...

), James A. Allison (partner in Prest-O-Lite

Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) is an American chemical company headquartered in Seadrift, Texas. It has been a wholly owned subsidiary of Dow Chemical Company since 2001. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more fu ...

) and he invested in what became Indianapolis Motor Speedway

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway is a motor racing circuit located in Speedway, Indiana, United States, an enclave suburb of Indianapolis, Indiana. It is the home of the Indianapolis 500 and the Brickyard 400, and and formerly the home of the U ...

, which is now surrounded by the city of Indianapolis. The first automobile race in August 1909 ended in disaster. The loose rock track led to numerous crashes, fires, terrible injuries to race-car drivers and spectators, and deaths. The race was halted and cancelled when only halfway completed.

Undeterred, Fisher convinced the investors to install 3.2 million paving bricks, leading to the famous nickname "the brickyard". (This persists, though it has since been resurfaced except for a three foot wide strip at the pole.) The speedway reopened, and on Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who died while serving in the United States Armed Forces. It is observed on the last Monday of May.

It i ...

, May 30, 1911, 80,000 spectators paid the $1 admission (and many thousands more unpaid in overlooking buildings and trees) and watched the 500-mile (800 km) event, the first in a long line of races known as the Indianapolis 500

The Indianapolis 500, formally known as the Indianapolis 500-Mile Race, and commonly shortened to Indy 500, is an annual automobile race held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Speedway, Indiana, United States, an enclave suburb of Indian ...

.

Lincoln Highway

In 1913, foreseeing the automobile's impact on American life, Fisher conceived and was instrumental in the planning, development, and construction of theLincoln Highway

The Lincoln Highway is one of the first transcontinental highways in the United States and one of the first highways designed expressly for automobiles. Conceived in 1912 by Indiana entrepreneur Carl G. Fisher, and formally dedicated Octob ...

, the first road across America, which connected New York City to San Francisco. Fisher estimated the highway, an improved, hard-surfaced road stretching almost , would cost $10 million. Fellow industrialists Frank Seiberling

Franklin Augustus "Frank" Seiberling (October 6, 1859 – August 11, 1955), also known as F.A. Seiberling, was an American innovator and entrepreneur best known for co-founding the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company in 1898 and the Seiberling Rubber ...

and Henry Bourne Joy

Henry Bourne Joy (November 23, 1864 – November 6, 1936) was an American businessman and President of the Packard Motor Car Company. He was a major developer of automotive activities as well as being a social activist.

In 1913, Joy and ...

helped Fisher with their promotional skills, together creating the Lincoln Highway Association. Much of the highway was paid for by contributions from automobile manufacturers and suppliers, a policy bitterly opposed by Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

.

Former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

and Thomas A. Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

, both friends of Fisher's, sent checks, as well as the then-President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, who has been noted as the first U.S. President to make frequent use of an automobile for what was described as stress-relief relaxation rides.

In 1919, as World War I was ending, the U.S. Army undertook its first transcontinental motor convoy along the Lincoln Highway. One of the young Army officers was Dwight David Eisenhower, then a lt. colonel, who credited the experience when supporting construction of the Interstate Highway System when he became President of the United States in 1952.

Dixie Highway

Fisher next turned his attention to creating the Dixie Highway, a network of north-south routes extending from theUpper Peninsula of Michigan

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan—also known as Upper Michigan or colloquially the U.P. or Yoop—is the northern and more elevated of the two major landmasses that make up the U.S. state of Michigan; it is separated from the Lower Peninsula of ...

to southern Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, which he felt would provide an ideal way for residents of his home state to vacation in southern Florida. In September 1916, Fisher and Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston

Samuel Moffett Ralston (December 1, 1857 – October 14, 1925) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served as the 28th governor of the U.S. state of Indiana and a United States senator from Indiana.

Born into a large imp ...

attended a celebration opening the roadway from Indianapolis to Miami.

Miami Beach

The future City of Miami Beach became Fisher's next big project. On a vacation to Miami around 1910, he saw potential in the swampy, bug-infested stretch of land between Miami and the ocean. He knew earlier pioneers needed working capital and ideas. His mind transformed the ofmangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows mainly in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. Mangroves grow in an equatorial climate, typically along coastlines and tidal rivers. They have particular adaptations to take in extra oxygen a ...

swamp and beach into the perfect vacation destination for his automobile-industry friends. His wife and he bought a vacation home there in 1912, and he began acquiring land. Paul Reyes, "Letter from Florida: Paradise Swamped: the boom and bust of the middle-class cream," ''Harper's

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the United States. ''Harper's Magazine'' has ...

'', pp. 39–40. Abstract aHarper's Archives

Accessed August 5, 2010. Though he did not invent the name Miami Beach, he popularized it. He platted the second plat in Miami Beach, following the Lummus Brothers. Fisher continued his wise investment in infrastructure. The

Collins Bridge

The Collins Bridge was a bridge that crossed Biscayne Bay between Miami and Miami Beach, Florida. At the time it was completed, it was the longest wooden bridge in the world. It was built by farmer and developer John S. Collins (1837–1928) wi ...

across Biscayne Bay

Biscayne Bay is a lagoon with characteristics of an estuary located on the Atlantic coast of South Florida. The northern end of the lagoon is surrounded by the densely developed heart of the Miami metropolitan area while the southern end is large ...

between Miami and the barrier island

Barrier islands are a Coast#Landforms, coastal landform, a type of dune, dune system and sand island, where an area of sand has been formed by wave and tidal action parallel to the mainland coast. They usually occur in chains, consisting of an ...

that became Miami Beach was built by John S. Collins (1837–1928), an earlier farmer and developer originally from New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. Collins, then 75 years old, had run out of money before he could complete his bridge. Fisher lent him the money in trade for of land. The new -mile (4 km) wooden toll bridge

A toll bridge is a bridge where a monetary charge (or '' toll'') is required to pass over. Generally the private or public owner, builder and maintainer of the bridge uses the toll to recoup their investment, in much the same way as a toll road ...

opened on June 12, 1913.

Fisher financed the dredging of Biscayne Bay to create its vast residential islands. He later built several landmark luxury hotels, including the Flamingo Hotel

Flamingo Las Vegas (formerly the Flamingo Hilton) is a casino hotel on the Las Vegas Strip in Paradise, Nevada. It is owned and operated by Caesars Entertainment. The Flamingo includes a casino and a 28-story hotel with 3,460 rooms.

The res ...

, that were meant to attract the wealthy and celebrated elite to convince them to buy permanent residences in the area.

Although a dedicated enthusiast of automobile travel, Fisher was aware that wealthy vacationers in those days often preferred to cross the long distances to southeastern Florida by

Although a dedicated enthusiast of automobile travel, Fisher was aware that wealthy vacationers in those days often preferred to cross the long distances to southeastern Florida by railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

, a tradition begun by some families years earlier with Henry M. Flagler's Florida East Coast Railway

The Florida East Coast Railway is a Class II railroad operating in the U.S. state of Florida, currently owned by Grupo México.

Built primarily in the last quarter of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, the FEC was a p ...

(FEC) and the resorts he established at places like St. Augustine and Palm Beach, and eventually Miami, the southern terminus of the FEC, where he built the well-known and later infamous Royal Palm Hotel.

In developing Miami Beach's potential for resort hotels, Fisher needed a transportation connection for the from the FEC railroad station in Miami.

The solution he developed was the Miami Beach Railway, an electric street railway

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which Rolling stock, vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some ...

system that served the additional purpose of providing electric service. Other investors and he formed the Miami Beach Electric Company and the Miami Beach Railway Co. It began service on December 14, 1920, and ran from downtown Miami, where it shared tracks with Miami's own trolley system, to the County Causeway (renamed MacArthur Causeway

The General Douglas MacArthur Causeway is a six-lane causeway that connects Greater Downtown Miami, Downtown Miami to South Beach via Biscayne Bay in Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County.

The highway is the singular roadway connecting ...

after World War II). After crossing Biscayne Bay to Miami Beach, the tracks looped around the section of Miami Beach south of 47th Street. Around 1926, Florida Power and Light acquired Fisher's streetcar system, and expanded it, double tracking the line across the causeway. While sale of electric service was a growth industry across the United States, though, the street railway portion went into a period of decline, along with the entire industry. All rail service between Miami and Miami Beach was terminated on October 17, 1939.

Even with the new street railway connecting with the FEC, while wealthy people came to vacation, only a few were buying land or building homes. The U.S. public was apparently slow to catch on to the vacation land and homes Fisher envisioned for Florida. His investments in Miami Beach were not paying off, at least not until he again used his promotional skills, which had worked so well years earlier in Indiana.

Ever the innovative promoter, Fisher seemed tireless in his efforts to draw attention to Miami Beach, a story recounted by PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

. Fisher had acquired a baby elephant named "Rosie", that was a favorite with newspaper photographers. In 1921, he got free publicity all across the country with what would be called today a promotional "photo-op" of Rosie serving as a "golf caddy" for vacationing President-elect Warren Harding. Billboards of bathing beauties enjoying white beaches and blue ocean waters appeared around the country. Fisher even purchased a huge, illuminated sign proclaiming "It's June in Miami" in Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and Neighborhoods in New York City, neighborhood in the Midtown Manhattan section of New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway (Manhattan), ...

.

During the Florida land boom of the 1920s

The first real estate bubble in Florida was primarily caused by the economic prosperity of the 1920s coupled with a lack of knowledge about List of Florida hurricanes, storm frequency and poor Building code, building standards.

This pioneering e ...

, real-estate sales took off as Americans discovered their automobiles and the paved Dixie Highway, which through no coincidence led to the foot of the Collins Bridge. Fewer than 1,000 year-round residents lived in Miami Beach in 1920. In the next five years, the resident population of the Miami Beach area grew 440%. People from all over the country flocked to South Florida in hopes of getting rich buying and selling real estate. They sent home tales of riches being made when orange groves and swamp lands were subdivided, sold, and developed.

The art of the swap, which helped fund the Collins Bridge, was apparently the source of great satisfaction to Fisher. He had bought another that now form Fisher Island from Dana A. Dorsey, South Florida's first African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

millionaire, and had begun some development there in 1919. Five years later, he traded seven acres of Fisher Island to William Kissam Vanderbilt II

William Kissam Vanderbilt II (October 26, 1878 – January 8, 1944) was an American motor racing enthusiast and yachtsman, and a member of the prominent Vanderbilt family.

Early life

He was born on October 26, 1878, in New York City, the secon ...

of the famous and wealthy Vanderbilt family, for the latter's 150-ft steam yacht ''Eagle''. Vanderbilt used the property, later expanded to 13 acres, to create an enclave even more luxurious and exclusive than many of Miami Beach's finest.

The Miami Yacht Club that Fisher built in 1924 was later converted into a private mansion that was extensively renovated in 2017; the property was on the market for $65 million in May 2018.

By 1926, Fisher was worth an estimated $50-100 million, depending on the source. He could have been financially secure for life. The Great Miami Hurricane of 1926, alcoholism, and the Great Depression of 1929 set him back. Always ready for a new idea, Fisher was known for moving from project to project. Success or failure had never stopped him from attempting something new. In her 1947 book, his ex-wife Jane Watts Fisher quoted him as replying, when she had hoped that he would slow down at some point, "I don't have time to take time." Instead, he redirected his promotional efforts to yet another new project far to the north.

Montauk, Long Island

In 1926, Fisher began working on a "Miami Beach of the North". His project at Montauk at the eastern tip ofLong Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

in New York was to provide a warm-season counterpart to the Florida development. Four associates and he purchased and built a luxurious hotel, office building, marina, and attractions. One source stated that they built about "30 Tudor-style buildings, including the lavish Montauk Manor and a yacht club."

The project built roads, planted nurseries, laid water pipes, and built houses. He built Montauk Manor, which still exists as a luxury resort today (pictured at right). He also built the Montauk Tennis Auditorium.

Because of financial reversals suffered by Fisher, the Montauk project went into receivership in 1932. According to his wife Jane, Montauk "was Carl’s first and only failure", but she died before Fisher's most significant losses.

The Carl Fisher Tower stands in the middle of Montauk at approximately 100 feet tall.

Later years

In 1925, Fisher's wealth was estimated as exceeding $50 million. In later years, he borrowed heavily and the hurricane in September 1926 damaged a large part of Miami Beach and reduced tourism. The losses in his real-estate ventures and the crash of 1929 left Fisher virtually penniless. "Fisher's financial house of cards began to collapse", according to a

In 1925, Fisher's wealth was estimated as exceeding $50 million. In later years, he borrowed heavily and the hurricane in September 1926 damaged a large part of Miami Beach and reduced tourism. The losses in his real-estate ventures and the crash of 1929 left Fisher virtually penniless. "Fisher's financial house of cards began to collapse", according to a PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

report, and the Stock Market Crash of 1929 (followed by the Great Depression) "sealed Fisher's fate".

One source indicates that during the years before his death, Fisher was living in a modest cottage on Miami Beach.

For his final project, in 1938, Fisher developed and built Key Largo's Caribbean Club, a fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment (Freshwater ecosystem, freshwater or Marine ecosystem, marine), but may also be caught from Fish stocking, stocked Body of water, ...

club for men who were not rich. After he died, the club was turned into a casino. Despite reports, no evidence shows that '' Key Largo'' was filmed there in 1948, according to research completed in 2014.

Fisher died July 15, 1939, at age 65, of a stomach hemorrhage in a Miami Beach hospital, following a lengthy illness compounded by alcoholism. His pallbearers included Barney Oldfield, William Vanderbilt, and Gar Wood. He was interred at the family mausoleum at Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high poi ...

in Indianapolis.

Legacy

On July 15, 1939, the ''Miami Daily News'' noted Fisher's ingenuity was influential and guided to earlier Miami Beach pioneers, summing him up: "Carl G. Fisher, who looked at a piece of swampland and visualized the nation's greatest winter playground, .... he once said "I could just as easily have started a cattle ranch."Will Rogers

William Penn Adair Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. He was born as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, in the Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma ...

remembered Fisher as a Florida pioneer with these words: Fisher was the first man to discover that there was sand under the water... andthat could hold up a real estate sign. He made the dredge the national emblem of Florida.Howard Kleinburg, an author and Miami Beach historian described Fisher:

If you look at Fisher's entire life, it's a marathon. It's a race. It was a race to achieve the top of whatever field he was in at the time. Everything he did he went into it with his heart, his soul, his money, and he would not stop until he reached the end. He wanted to be there the quickest and first...In 1947, Jane Fisher, his ex-wife (who married him in 1909 and was divorced in 1926), wrote a book about his life. ''Fabulous Hoosier'' was published by R.M. McBride and Co. She wrote:

He was all speed. I don't believe he ever thought in terms of money. He made millions, but they were incidental. He often said, "I just like to see the dirt fly."Among his most successful real-estate ideas was to pioneer and to encourage "whites only" property deed restrictions and physical racial segregation. Fisher's goal was "to create a mecca for the wealthy" on a little-known barrier island called Miami Beach, Florida. Under Fisher's aggressive influence, Miami Beach became a Sundown Town that did not allow people of color to live or even be on the island after dark. This had lasting effects on Miami Beach's housing patterns and demographics. Though he recanted on earlier "gentiles only" policies and sought the help of white Jewish investors for capital for his Miami Beach holdings, he never recanted on his philosophy of a "whites only" Miami Beach. In 1952, Carl Graham Fisher was inducted into the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame, and the

Automotive Hall of Fame

The Automotive Hall of Fame is a hall of fame and museum honoring influential figures in the history of the automotive industry. Located in Dearborn, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, US. The Hall of Fame is part of the MotorCities National Herita ...

in 1971. In 1998, PBS produced a program about Fisher titled ''Mr. Miami Beach'' as a part of the ''American Experience'' series.

He has also a school in Speedway, Indiana

Speedway is a town in Wayne Township, Marion County, Indiana, United States. The population was 13,952 at the 2020 census, up from 11,812 in 2010. Speedway, which is an enclave of Indianapolis, is the home of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

H ...

, named for him - Carl G. Fisher Elementary School.

Fisher was named to the List of Great Floridians.

He was inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America

The Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (MSHFA) is a hall of fame that honors motorsports competitors and contributors from the United States from all disciplines, with categories for Open Wheel, Stock Cars, Powerboats, Drag Racing, Motorcycles ...

in 2018.Carl Fisherat the

Motorsports Hall of Fame of America

The Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (MSHFA) is a hall of fame that honors motorsports competitors and contributors from the United States from all disciplines, with categories for Open Wheel, Stock Cars, Powerboats, Drag Racing, Motorcycles ...

In 2014, a historic marker was erected on 150 Courthouse Square, Greensburg, IN 46240.

See also

* *Cocolobo Cay Club

The Cocolobo Cay Club, later known as the Coco Lobo Club, was a private club on Adams Key in what is now Biscayne National Park, Florida. It was notable as a destination for the rich and the politically well-connected. Four presidents (Warren G. ...

, a 1922 Fisher project that was later incorporated into Biscayne National Park

Biscayne National Park is a national park of the United States located south of Miami, Florida, in Miami-Dade County. The park preserves Biscayne Bay and its offshore barrier reefs. Ninety-five percent of the park is water, and the shore of th ...

References

Sources

*Clymer, Floyd.Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925

' New York: Bonanza Books, 1950. *Fisher, Jane. ''Fabulous Hoosier'' New York, New York: R. M. McBride and Co., 1947 *Fisher, Jerry M. ''The Pacesetter: The Untold Story of Carl G. Fisher'' Ft. Bragg, California: Lost Coast Press, 1998

Further reading

*Foster, Mark S.Castles in the Sand: The Life and Times of Carl Graham Fisher

'. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 2000. *Lummus, J. N

''The Miracle of Miami Beach''

(Self published; Miami, Florida), 1944 * Nolan, David.

Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida

'. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984.

External links

Lincoln Highway Association

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fisher, Carl G. 1874 births 1939 deaths American automotive pioneers American segregationists Antisemitism in Florida Businesspeople from Indianapolis Burials at Crown Hill Cemetery People from Montauk, New York People from Greensburg, Indiana People from Miami Beach, Florida White nationalism in Florida