carbonari on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Carbonari () was an informal network of secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in

The Carbonari first arose during the resistance to the French occupation, notably under

The Carbonari first arose during the resistance to the French occupation, notably under

The Carbonari were beaten but not defeated; they took part in the revolution of July 1830 that supported the liberal policy of King Louis Philippe of France on the wings of victory for the uprising in Paris. The Italian Carbonari took up arms against some states in central and northern Italy, particularly the Papal States and Modena.

Ciro Menotti was to take the reins of the initiative, trying to find the support of Duke Francis IV of Modena, who pretended to respond positively in return for granting the title of King of Italy, but the Duke made the double play and Menotti, virtually unarmed, was arrested the day before the date fixed for the uprising. Francis IV, at the suggestion of the Austrian statesman

The Carbonari were beaten but not defeated; they took part in the revolution of July 1830 that supported the liberal policy of King Louis Philippe of France on the wings of victory for the uprising in Paris. The Italian Carbonari took up arms against some states in central and northern Italy, particularly the Papal States and Modena.

Ciro Menotti was to take the reins of the initiative, trying to find the support of Duke Francis IV of Modena, who pretended to respond positively in return for granting the title of King of Italy, but the Duke made the double play and Menotti, virtually unarmed, was arrested the day before the date fixed for the uprising. Francis IV, at the suggestion of the Austrian statesman

In 1820, the Neapolitan Carbonari once more took up arms, to wring a constitution from King Ferdinand I. They advanced against the capital from

In 1820, the Neapolitan Carbonari once more took up arms, to wring a constitution from King Ferdinand I. They advanced against the capital from

Charbonnerie démocratique

was formed among the French Republicans; after 1841, nothing more was heard of it. Carbonari was also to be found in Spain, but their numbers and importance were more limited than in the other Romance countries. In 1830, Carbonari took part in the

in JSTOR

* Shiver, Cornelia. "The Carbonari". ''Social Science'' (1964): 234-241

in JSTOR

* * Spitzer, Alan Barrie. ''Old hatreds and young hopes: the French Carbonari against the Bourbon Restoration'' (Harvard University Press, 1971). Attribution: * *

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. Although their goals often had a patriotic

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

and liberal basis, they lacked a clear immediate political agenda. They were a focus for those unhappy with the repressive political situation in Italy following 1815, especially in the south of the Italian peninsula. Members of the Carbonari, and those influenced by them, took part in important events in the process of Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

(called the ''Risorgimento''), especially the failed Revolution of 1820, and in the further development of Italian nationalism

Italian nationalism () is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness i ...

. The chief purpose was to defeat tyranny and establish a constitutional government. In the north of Italy, other groups, such as the Adelfia and the Filadelfia, were associated organizations.

Organization

The Carbonari were asecret society

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ag ...

divided into small covert cells scattered across Italy. Although agendas varied, evidence suggests that despite regional variations, most of them agreed upon the creation of a liberal, unified Italy.. The Carbonari were anti-clerical in both their philosophy and programme. The Papal constitution Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo and the encyclical '' Qui pluribus'' were directed against them. The controversial document Alta Vendita, which called for a liberal or modernist takeover of the Catholic Church, was attributed to the Sicilian Carbonari.

History

Origins

Although it is not clear where they were established, they first came to prominence in theKingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

during the Napoleonic wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. Although some of the society's documents claimed that it had origins in medieval France, and that its progenitors were under the sponsorship of Francis I of France

Francis I (; ; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis&nbs ...

during the sixteenth century, this claim cannot be verified by outside sources. Although a plethora of theories have been advanced as to the origins of the Carbonari, the organization most probably emerged as an offshoot of Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, as part of the spread of liberal ideas from the French Revolution. They first became influential in the Kingdom of Naples (under the control of Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

) and in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, the most resistant opposition to the ''Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

''.

As a secret society that was often targeted for suppression by conservative governments, the Carbonari operated largely in secret. The name ''Carbonari'' identified the members as rural "charcoal-burners"; the place where they met was called a "Barack", the members called themselves "good cousins", while people who did not belong to the Carbonari were "Pagani". There were special ceremonies to initiate the members.

The aim of the Carbonari was the creation of a constitutional monarchy or a republic; they wanted also to defend the rights of common people against all forms of absolutism. Carbonari, to achieve their purpose, talked of fomenting armed revolts.

The membership was separated into two classes—apprentice and master. There were two ways to become a master: through serving as an apprentice for at least six months or by already being a Freemason upon entry.. Their initiation rituals were structured around the trade of charcoal-selling, suiting their name.

In 1814 the Carbonari wanted to obtain a constitution for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies () was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1861 under the control of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbons. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by popula ...

by force. The Bourbon king, Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies

Ferdinand I (Italian language, Italian: ''Ferdinando I''; 12 January 1751 – 4 January 1825) was Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, King of the Two Sicilies from 1816 until his death. Before that he had been, since 1759, King of Naples as Ferdinand I ...

, was opposed to them. The Bonapartist Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

had wanted to create a united and independent Italy. In 1815 Ferdinand I found his kingdom swarming with them. He found an unhoped-for ally in the secret sect of the Calderari, that had separated from the Carbonari in 1813. Staunchly Catholics and legitimists, the Calderari swore to defend the Church and vowed eternal hatred to Freemasons and Carbonari. Society in the ''Regno'' comprised nobles, officers of the army, small landlords, government officials, peasants, and priests, with a small urban middle class. Society was dominated by the Papacy. On 15 August 1814, Cardinals Ercole Consalvi

Ercole Consalvi (8 June 1757 – 24 January 1824) was a deacon and cardinal of the Catholic Church, who served twice as Cardinal Secretary of State for the Papal States and who played a crucial role in the post-Napoleonic reassertion of the legit ...

and Bartolomeo Pacca

Bartolomeo Pacca (27 December 1756, Benevento – 19 April 1844, Rome) was an Italian cardinal, scholar, and statesman as Cardinal Secretary of State. Pacca served as apostolic nuncio to Cologne, and later to Lisbon.

Biography

Bartolomeo Pacca ...

issued an edict forbidding all secret societies, to become members of these secret associations, to attend their meetings, or to furnish a meeting-place for such, under severe penalties.

1820 and 1821 uprisings

The Carbonari first arose during the resistance to the French occupation, notably under

The Carbonari first arose during the resistance to the French occupation, notably under Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

, the Bonapartist King of Naples

The following is a list of rulers of the Kingdom of Naples, from its first Sicilian Vespers, separation from the Kingdom of Sicily to its merger with the same into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Kingdom of Naples (1282–1501)

House of Anjou

...

. However, once the wars ended, they became a nationalist organization with a marked anti- Austrian tendency and were instrumental in organizing revolutions in Italy in 1820–1821 and 1831.

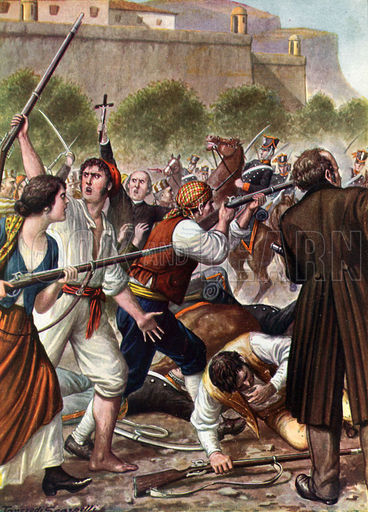

The 1820 revolution began in Naples against King Ferdinand I. Riots, inspired by events in Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

, Spain that same year, took place in Naples, bandying anti-absolutist goals and demanding a liberal constitution. On 1 July, two officers, Michele Morelli and Joseph Silvati (who had been part of the army of Murat under Guglielmo Pepe

Guglielmo Pepe (13 February 1783 – 8 August 1855) was an Italian general and patriot. He was brother to Florestano Pepe and cousin to Gabriele Pepe. He was married to Mary Ann Coventry, a Scottish woman who was the widow of John Bort ...

) marched towards the town of Nola in Campania at the head of their regiments of cavalry.

Worried about the protests, King Ferdinand agreed to grant a new constitution and the adoption of a parliament. The victory, albeit partial, illusory, and apparent, caused a lot of hope in the peninsula and local conspirators, led by Santore di Santarosa, marched toward Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

and 12 March 1821 obtained a constitutional monarchy and liberal reforms as a result of Carbonari actions. However, the Holy Alliance did not tolerate such revolutionary compromises and in February 1821 sent an army that defeated the outnumbered and poorly equipped insurgents in the south. In Piedmont, King Vittorio Emanuele I

Victor Emmanuel I (; 24 July 1759 – 10 January 1824) was the Counts and dukes of Savoy, Duke of Savoy, List of monarchs of Sardinia, King of Sardinia and ruler of the Savoyard state, Savoyard states from 4 June 1802 until his reign ended in 1 ...

, undecided about what to do, abdicated in favour of his brother Charles Felix of Sardinia

Charles Felix (; 6 April 1765 – 27 April 1831) was the King of Sardinia and ruler of the Savoyard states from 12 March 1821 until his death in 1831. He was the last male-line member of the House of Savoy that started with Victor Amadeus I ...

; but Charles Felix, more resolute, invited an Austrian military intervention. On 8 April, the Habsburg army defeated the rebels, and the uprisings of 1820–1821, triggered almost entirely by the Carbonari, ended up collapsing.

On 13 September 1821, Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII (; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823) was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again ...

with the bull ''Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo'' condemned the Carbonari as a Freemason secret society, excommunicating its members.

Among the principal leaders of the Carbonari, Morelli and Silvati were sentenced to death; Pepe went into exile; Federico Confalonieri, Silvio Pellico and Piero Maroncelli were imprisoned.

1831 uprisings

The Carbonari were beaten but not defeated; they took part in the revolution of July 1830 that supported the liberal policy of King Louis Philippe of France on the wings of victory for the uprising in Paris. The Italian Carbonari took up arms against some states in central and northern Italy, particularly the Papal States and Modena.

Ciro Menotti was to take the reins of the initiative, trying to find the support of Duke Francis IV of Modena, who pretended to respond positively in return for granting the title of King of Italy, but the Duke made the double play and Menotti, virtually unarmed, was arrested the day before the date fixed for the uprising. Francis IV, at the suggestion of the Austrian statesman

The Carbonari were beaten but not defeated; they took part in the revolution of July 1830 that supported the liberal policy of King Louis Philippe of France on the wings of victory for the uprising in Paris. The Italian Carbonari took up arms against some states in central and northern Italy, particularly the Papal States and Modena.

Ciro Menotti was to take the reins of the initiative, trying to find the support of Duke Francis IV of Modena, who pretended to respond positively in return for granting the title of King of Italy, but the Duke made the double play and Menotti, virtually unarmed, was arrested the day before the date fixed for the uprising. Francis IV, at the suggestion of the Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. ...

, had condemned him to death, along with many others among Menotti's allies. This was the last major effort by the secret group.

Aftermath

Nola

Nola is a town and a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, southern Italy. It lies on the plain between Mount Vesuvius and the Apennines. It is traditionally credited as the diocese that introduced bells to Christian worship.

...

under a military officer and Abbot Minichini. They were joined by General Pepe and many officers and government officials, and the king took an oath to observe the Spanish constitution in Naples. The movement spread to Piedmont, and Victor Emmanuel resigned from the throne in favour of his brother Charles Felix. The Carbonari secretly continued their agitation against Austria and the governments in a friendly connection with it. Pope Pius VII issued a general condemnation of the secret society of the Carbonari. The association lost its influence by degrees and was gradually absorbed into the new political organizations that sprang up in Italy; its members became affiliated especially with Mazzini's "Young Italy". From Italy, the organization was carried to France where it appeared as the Charbonnerie, which, was divided into verses. Members were especially numerous in Paris. The chief aim of the association in France also was political, namely, to obtain a constitution in which the conception of the sovereignty of the people could find expression. From Paris, the movement spread rapidly through the country, and it was the cause of several mutinies among the troops; it lost its importance after several conspirators were executed, especially as quarrels broke out among the leaders. The Charbonnerie took part in the Revolution of 1830; after the fall of the Bourbons, its influence rapidly declined. After this, Charbonnerie démocratique

was formed among the French Republicans; after 1841, nothing more was heard of it. Carbonari was also to be found in Spain, but their numbers and importance were more limited than in the other Romance countries. In 1830, Carbonari took part in the

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first of 1789–99. It led to the overthrow of King Cha ...

in France. This gave them hope that a successful revolution might be staged in Italy. A bid in Modena

Modena (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. It has 184,739 inhabitants as of 2025.

A town, and seat of an archbis ...

was an outright failure, but in February 1831, several cities in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

rose and flew the Carbonari tricolour. A volunteer force marched on Rome but was destroyed by Austrian troops who had intervened at the request of Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI (; ; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in June 1846. He had adopted the name Mauro upon enteri ...

. After the failed uprisings of 1831, the governments of the various Italian states cracked down on the Carbonari, who now virtually ceased to exist. The more astute members realized they could never take on the Austrian army in open battle and joined a new movement, Giovane Italia ('Young Italy') led by the nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

, in which many members would trace their origins and inspiration to the Carbonari. Rapidly declining in influence and members, the Carbonari practically ceased to exist, although the official history of this important company had continued, wearily, until 1848. Independent from French Philadelphians were instead the homonymous ''carbonara'' group born in Southern Italy, especially in Puglia and in the Cilento, between 1816 and 1828. In Cilento, in 1828, an insurrection of Philadelphia, who called for the restoration of the Neapolitan Constitution of 1820, was fiercely repressed by the director of the Bourbon police Francesco Saverio Del Carretto, whose violent retaliation included the destruction of the village of Bosco.

Holy protector

The members of Carboneria recognize Theobald of Provins as thepatron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of charcoal burners as well as tanners. In fact, for example, Felice Orsini

Felice Orsini (; ; 10 December 1819 – 13 March 1858) was an Italian revolutionary and leader of the '' Carbonari'' who tried to assassinate Napoleon III, Emperor of the French.

Early life

Felice Orsini was born at Meldola in Romagna, th ...

's father, who belonged to Carboneria, wanted to give him the name of Orso Teobaldo Felice.

Prominent members

Prominent members of the Carbonari included: * Gabriele Rossetti * Amand Bazard * Silvio Pellico (1788–1854) and Pietro Maroncelli (1795–1846) : both were imprisoned by the Austrians for years, many of which they spent in Spielberg fortress inBrno

Brno ( , ; ) is a Statutory city (Czech Republic), city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava (river), Svitava and Svratka (river), Svratka rivers, Brno has about 403,000 inhabitants, making ...

, Southern Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

. After his release, Pellico wrote the book ''Le mie prigioni'', describing in detail his ten-year ordeal. Maroncelli lost one leg in prison and was instrumental in translating and editing of Pellico's book in Paris (1833).

*Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

*Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette (; 6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (), was a French military officer and politician who volunteered to join the Conti ...

(hero of the American and French Revolutions),

*Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (the future French emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

) Almost certain but highly disputed.

*French revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui.

*Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

*Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

Legacy

In Portugal

The Portuguese Carbonari () was first founded there in 1822 but was soon disbanded. A new organization of the same name and claiming to be its continuation was founded in 1896 by Artur Augusto Duarte da Luz de Almeida. This organization was active in efforts to educate the people and was involved in various antimonarchist conspiracies. Most notably, ''Carbonária'' members were active in the assassination of King Charles I and his heir, Prince Louis Philip in 1908. ''Carbonária'' members also played a part in the5 October 1910 revolution

5 October 1910 Revolution () was the overthrow of the centuries-old List of Portuguese monarchs, Portuguese monarchy and its replacement by the First Portuguese Republic. It was the result of a ''coup d'état'' organized by the Portuguese Repub ...

that deposed the Constitutional Monarchy and implemented the republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

. One commonality among them was their hostility to the Church and they contributed to the republic's anticlericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to clergy, religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secul ...

.

Elsewhere in Europe

Two results of great importance in the progress of the European Revolution (Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

) proceeded from the events that occurred at Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

in 1820-21. One was the reorganization of the Carbonari, consequent upon the publicity given to their organization when it had brought about the revolution (and the secrecy in which it had hitherto been enveloped was no longer deemed necessary); the other was the extension of the organization beyond the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

. When the Neapolitan revolution had been effected, the Carbonari emerged from their mystery, published their constitution statutes, and ceased to conceal their program and their cards of membership.

In particular, the dispersion of the Carbonari leaders had, at the same time, the effect of extending their influence in France. General Guglielmo Pepe

Guglielmo Pepe (13 February 1783 – 8 August 1855) was an Italian general and patriot. He was brother to Florestano Pepe and cousin to Gabriele Pepe. He was married to Mary Ann Coventry, a Scottish woman who was the widow of John Bort ...

proceeded to Barcelona when the counter-revolution was imminent at Naples and his life was no longer safe there; and to the same city went several of the Piedmontese revolutionists when the country was Austrianized after the same lawless fashion. The dispersion of Scalvini and Ugoni that took refuge at Geneva and others of the proscribed that proceeded to London added to the progress which Carbonarism was making in France, suggested to General Pepe the idea of an international secret society, which would combine for a common purpose the advanced political reformers of all the European States.

South America

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

has been called the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

and Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. In 1836, Garibaldi took up the cause of Republic of Rio Grande do Sul in its attempt to separate from the Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and Uruguay until the latter achieved independence in 1828. The empire's government was a Representative democracy, representative Par ...

, joining the rebels known as the Ragamuffins in the Ragamuffin War

The Ragamuffin War, also known as the Ragamuffin Revolution or Heroic Decade, was a republican uprising that began in southern Brazil, in the province (current state) of Rio Grande do Sul in 1835. The rebels were led by Generals Bento Gonçalv ...

(1835-1845). In 1841, Garibaldi moved to Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

. In 1842, he took command of the Uruguayan fleet and raised an "Italian Legion" of soldiers for the Uruguayan Civil War

The Uruguayan Civil War, also known in Spanish as the ''Guerra Grande'' ("Great War"), was a series of armed conflicts between the leaders of Uruguayan independence. While officially the war lasted from 1839 until 1851, it was a part of armed ...

(1839-1851). He aligned his forces with a faction composed of the Uruguayan Colorados and the Argentine Unitarios. This faction received support from the French and British Empires in their struggle against the forces of the Uruguayan Government and Argentine Federales.

In literature

The story '' Vanina Vanini'' by Stendhal involved a hero in the Carbonari and a heroine who became obsessed with this. It was made into a film in 1961.Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

's story " The Pavilion on the Links" features the Carbonari as the villains of the plot.

Katherine Neville's novel '' The Fire'' features the Carbonari as part of a plot involving a mystical chess service.

In Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1860), a mystery novel and early sensation novel, and for ''The Moonsto ...

' " The Woman in White" the character of Professor Pesca is a member of 'The Brotherhood', an organization placed contemporaneously with, and similarly featured as, the Carbonari. Clyde Hyder suspects that the model for Prof. Pesca was Gabriele Rossetti, who was a member of the Carbonari, as well as an Italian teacher resident in London during the 1840s.

Anton Felix Schindler's biography of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

"Beethoven, as I Knew Him" states that his close connection with the composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

began in 1815 when the latter requested an account of Schindler's involvement with a riot of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's supporters in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, who were agitating against the Carbonari uprisings. Schindler was arrested and lost a year at college. Beethoven was sympathetic and, as a result, became a close friend of Schindler.

The Carbonari are mentioned prominently in the Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a Detective fiction, fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "Private investigator, consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with obser ...

short story " The Adventure of the Red Circle" (1911), written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Carbonari are also mentioned briefly in the book " Resurrection Men" by T. K. Welsh, in which the main character's father is a member of the secret organization.

They feature in Tim Powers

Timothy Thomas Powers (born February 29, 1952) is an American science fiction and fantasy fiction, fantasy author. His first major novel was ''The Drawing of the Dark'' (1979), but the novel that earned him wide praise was ''The Anubis Gates'' ...

' '' The Stress of Her Regard'' as opponents of the vampire-backed Austrian Empire.

Mr. Settembrini's grandfather in Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

's ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann. It was first published in Germany in November 1924. Since then, it has gone through numerous editions and been translated into many languages. It is widely considered a seminal work of 20t ...

'' is said to be Carbonari.

The Carbonari are mentioned in ''The Hundred Days'' by Patrick O'Brian, part of the Aubrey-Maturin series.

Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian Medieval studies, medievalist, philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular ...

's '' The Cemetery of Prague'' mentions the Carbonari, with the main character joining them as a spy.

In The Horseman on the Roof by Jean Giono

Jean Giono (30 March 1895 – 8 October 1970) was a French writer who wrote works of fiction mostly set in the Provence region of France.

First period

Jean Giono was born to a family of modest means, his father a cobbler of Piedmontese descent a ...

, the character of Angelo Pardi is a young Italian Carbonaro colonel of hussars

They also appear in Carmen Mola's novel ''La Bestia'' (2021).

Film adaptations

* '' Vanina Vanini'', byRoberto Rossellini

Roberto Gastone Zeffiro Rossellini (8 May 1906 – 3 June 1977) was an Italian film director, screenwriter and producer. He was one of the most prominent directors of the Italian neorealist cinema, contributing to the movement with films such a ...

(1961), adaptation of Stendhal's novel of the same name.

* '' Nell'anno del Signore'', by Luigi Magni (1969).

* '' Allonsanfan'', by the Taviani brothers (1973).

* '' The Horseman on the Roof'', by Jean-Paul Rappeneau

Jean-Paul Rappeneau (; born 8 April 1932) is a French film director and screenwriter.

Career

He started out in film as an assistant and screenwriter collaborating with Louis Malle on ''Zazie dans le métro'' in 1960 and ''Vie privée'' in 1961. ...

(1995), adaptation of Jean Giono's novel of the same name.

See also

*Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

* Communist League

* Four Sergeants of La Rochelle

* League of the Just

The League of the Just () or League of Justice was a masonic international revolutionary organization. It was founded in 1836 by branching off from its ancestor, the , which had formed in Paris in 1834. The League of the Just was largely compos ...

* Secret society

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ag ...

* The Society of Seasons

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * Reinerman, Alan. "Metternich and the Papal Condemnation of the" Carbonari" (1821). ''Catholic Historical Review'' 54#1 (1968): 55-69in JSTOR

* Shiver, Cornelia. "The Carbonari". ''Social Science'' (1964): 234-241

in JSTOR

* * Spitzer, Alan Barrie. ''Old hatreds and young hopes: the French Carbonari against the Bourbon Restoration'' (Harvard University Press, 1971). Attribution: * *

External links

* {{Authority control Anti-Catholicism in Italy Anti-Catholicism in France Anti-Catholicism in Portugal Anti-Catholicism Anti-clericalism Secret societies in Italy Secret societies in France Freemasonry-related controversies