Captain James Stirling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Stirling

/ref> Throughout his career Stirling showed considerable diplomatic skill and was selected for a number of sensitive missions. Paradoxically, this was not reflected in his personal dealings with officialdom and his hopes for preferment received many rebuffs. Stirling also personally led the attack in Western Australia on a group of approximately seventy Bindjareb men, women and children now known as the

Stirling trained for

Stirling trained for

In the

In the  At the end of 1816 Stirling was commissioned to make a further detailed inspection of the conditions in Venezuela. From Güiria in the

At the end of 1816 Stirling was commissioned to make a further detailed inspection of the conditions in Venezuela. From Güiria in the

The Nyoongar people call the river Derbarl Yerrigan.

On 10 January 1697, the Dutch sea captain Willem De Vlamingh renamed it to the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large number of black swans they observed there. One hundred and thirty years later, the British ship ''Success'' arrived off the west coast of Australia on 5 March 1827 and anchored near the north east corner of Rottnest Island. The following day, the ship moved cautiously towards the coast and anchored about a mile from the mouth of the Swan. Lieutenant

The Nyoongar people call the river Derbarl Yerrigan.

On 10 January 1697, the Dutch sea captain Willem De Vlamingh renamed it to the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large number of black swans they observed there. One hundred and thirty years later, the British ship ''Success'' arrived off the west coast of Australia on 5 March 1827 and anchored near the north east corner of Rottnest Island. The following day, the ship moved cautiously towards the coast and anchored about a mile from the mouth of the Swan. Lieutenant  The next day, dragging across the shallows started at daybreak and continued until nightfall. Frazer, exploring on land, found a freshwater brook and Stirling named the nearby point of land ''Point Frazer''. Frazer also found a lagoon of fresh water and the party moved camp to beside it. On the following morning three armed Aboriginal warriors demonstrated their anger at the "invasion" (Stirling's word) of their territory with violent gestures, but eventually retired. During the day, the boats reached the Heirisson Islands and in the channel above them progress was much easier, but still slow, due to the winding of the river. On 11 March the boats passed through a long narrow stretch and encountered more Aboriginal people who threatened the boats with their spears from higher ground. When the boats reached more level terrain, gestures of goodwill defused the situation and the Aboriginals moved on.

On 12 March the boats reached a place where a tributary, later named ''

The next day, dragging across the shallows started at daybreak and continued until nightfall. Frazer, exploring on land, found a freshwater brook and Stirling named the nearby point of land ''Point Frazer''. Frazer also found a lagoon of fresh water and the party moved camp to beside it. On the following morning three armed Aboriginal warriors demonstrated their anger at the "invasion" (Stirling's word) of their territory with violent gestures, but eventually retired. During the day, the boats reached the Heirisson Islands and in the channel above them progress was much easier, but still slow, due to the winding of the river. On 11 March the boats passed through a long narrow stretch and encountered more Aboriginal people who threatened the boats with their spears from higher ground. When the boats reached more level terrain, gestures of goodwill defused the situation and the Aboriginals moved on.

On 12 March the boats reached a place where a tributary, later named ''

Stirling's original mission included a task to carry supplies to Melville Island. However, Darling had received further instructions to investigate the formation of a new settlement on the coast to the east of Melville Island.NSW State Record

Stirling's original mission included a task to carry supplies to Melville Island. However, Darling had received further instructions to investigate the formation of a new settlement on the coast to the east of Melville Island.NSW State Record

Archives

/ref> Accordingly, ''Success'' left Sydney on 19 May 1827 carrying an establishment force for a new settlement and accompanied by the brig ''Mary Elizabeth''. The two ships separated. ''Mary Elizabeth'' sailed to Melville Island and on 15 June ''Success'' anchored in Palm Bay, on the western side of Croker Island. Stirling quickly established that the island was unsuitable for settlement and sent a boat across to the mainland to explore Raffles Bay. The report being favourable, Stirling looked no further and on 18 June he went ashore with his officers to take possession of Raffles Bay and the surrounding territory in His Majesty's name. The establishment force and supplies were landed and Stirling named the settlement Fort Wellington, Australia, Fort Wellington. A month later, believing all to be well, Stirling set sail for Melville island. ''Success'' arrived at History of the Northern Territory#European exploration and settlement, Fort Dundas on Melville Island on 25 July and set sail again four days later for Madras, and then to Penang, to report to William Hall Gage, Admiral Gage, Commander of the Eastern Station. Stirling was keen to return home to see his family and to further his case for a settlement at the Swan River. However, Gage instructed him to base ''Success'' in Trincomalee Harbour, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he arrived on 4 January 1828. There he succumbed rapidly to the tropical climate and on 21 February three Royal Navy surgeons certified that he was so ill he should return immediately to England. The settlements at Fort Dundas and Fort Wellington rapidly got into difficulties with outbreaks of scurvy and fever, supply shortages and communication failures. The Melville Island outpost was abandoned in November 1828 and the Raffles Bay settlement was broken up in July 1829.

Celebrate W.A. site

* *

by Christopher John Pettitt for Normandy Historians , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, James 1791 births 1865 deaths People from North Lanarkshire Clan Stirling, James Explorers of Australia Governors of Western Australia Aboriginal genocide perpetrators Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Western Australian Legislative Council Royal Navy admirals Scottish mass murderers Scottish murderers of children Scottish politicians Japan–United Kingdom relations Settlers of Western Australia Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars People from Coatbridge 19th-century Australian politicians Australian city founders

Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Sir James Stirling (28 January 179122 April 1865) was a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

naval officer and colonial administrator. His enthusiasm and persistence persuaded the British Government to establish the Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just ''Swan River'', was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, an ...

and he became the first Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

and Commander-in-Chief of Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. In 1854, when Commander-in-Chief, East Indies and China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, East Indies and China was a formation of the Royal Navy from 1831 to 1865. Its naval area of responsibility was the Indian Ocean and the coasts of China and its navigable rivers.

The Commander-in-Chief was appointed in 18 ...

, Stirling on his own initiative signed Britain's first Anglo-Japanese Friendship Treaty

The was the first treaty between the United Kingdom and Japan, then under the administration of the Tokugawa shogunate. Signed on October 14, 1854, it paralleled the Convention of Kanagawa, a similar agreement between Japan and the United States s ...

.Dictionary of Australian BiographJames Stirling

/ref> Throughout his career Stirling showed considerable diplomatic skill and was selected for a number of sensitive missions. Paradoxically, this was not reflected in his personal dealings with officialdom and his hopes for preferment received many rebuffs. Stirling also personally led the attack in Western Australia on a group of approximately seventy Bindjareb men, women and children now known as the

Pinjarra massacre

The Pinjarra massacre, also known as the Battle of Pinjarra, occurred on 28 October 1834 in Pinjarra, Western Australia when a group of Binjareb Noongar people were attacked by a detachment of 25 soldiers, police, and settlers led by Governor ...

.

Stirling entered the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

at age 12 and as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

saw action in the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. Rapid promotion followed and when he was 21 he received his first command, the 28-gun sloop , and, in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

between the US and the UK, seized two prizes. ''Brazen'' carried the news of the end of that war to Fort Bowyer

Fort Bowyer was a short-lived earthen and stockade fortification that the United States Army erected in 1813 on Mobile Point, near the mouth of Mobile Bay in what is now Baldwin County, Alabama, but then was part of the Mississippi Territory. Th ...

and took part in carrying to England the British troops that had captured the fort. On return to the West Indies, Stirling made two surveys of the Venezuelan coast and reported on the strengths, attitudes and dispositions of the Spanish government and various revolutionary factions, later playing a role in the British negotiations with these groups.

In his second command, , he carried supplies and coinage to Australia, but with a covert mission to assess other nations' interest in the region and explore opportunities for British settlements. He is chiefly remembered for his exploration of the Swan River, followed by his eventual success in lobbying the British Government to establish a settlement there. On 30 December 1828, he was made Lieutenant-Governor of the colony-to-be. He formally founded the city of Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

and the port of Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

and oversaw the development of the surrounding area and on 4 March 1831 he was confirmed as Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the new territory, Western Australia, in which post he remained until in 1838 he resumed his naval career.

In October 1834 Stirling personally led a group of twenty-five police, soldiers and settlers in a punitive expedition against approximately seventy Bindjareb men, women and children camped on the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray; Ngarrindjeri language, Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta language, Yorta Yorta: ''Dhungala'' or ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is List of rivers of Australia, Aust ...

partly in retaliation for several murders and thefts. This bloody attack involving rifles and bayonets against spears is known as the Pinjarra Massacreand sometimes the Battle of Pinjarra. An uncertain number of Aboriginal men, women and children were killed during this encounter; Stirling reported 15 males killed, John Septimus Roe

John Septimus Roe (8 May 1797 – 28 May 1878) was the first Surveyor-General of Western Australia. He was a renowned explorer, a member of Western Australia's legislative and executive councils for nearly 40 years, but also a participant in ...

15–20, and an unidentified eyewitness 25–30 including 1 woman and several children with probably more floating down with the stream. One of Stirling's party was injured and one was injured and died about two weeks later, although it is uncertain if from existing injuries, injuries suffered during the massacre, poor medical treatment after the massacre, or a combination thereof. An uncertain number of Bindjareb were injured, and an uncertain number died of their injuries.

From 1840 to 1844, in command of the 80-gun , he patrolled the Mediterranean with instructions to "show the flag" and keep an eye on the French. In 1847, he was given command of the 120-gun first rate ship of the line and his first commission was to conduct Her Majesty, the Dowager Queen Adelaide

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen (Adelaide Amelia Louise Theresa Caroline; 13 August 1792 – 2 December 1849) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Queen of Hanover from 26 June 1830 to 20 June 1837 as the wife of King W ...

on trips to Lisbon and Madeira and then back to Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house in the style ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

. After that, ''Howe'' was assigned to the eastern Mediterranean, where she reinforced the squadron led by Vice Admiral Parker using gunboat diplomacy

Gunboat diplomacy is the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to the superior force.

The term originated in ...

to secure an uneasy peace in the region.

Stirling's fifth and final command was as Commander in Chief, China and the East Indies Station, and his flag, as Rear Admiral of the White, was hoisted on on 11 May 1854. Shortly afterwards news arrived that war had been declared on Russia. Stirling was anxious to prevent Russian ships from sheltering in Japanese ports and menacing allied shipping and, after lengthy negotiations through the Nagasaki Magistrate, concluded a Treaty of Friendship with the Japanese. The treaty was endorsed by the British Government, but Stirling was criticised in the popular press for not finding and engaging with the Russian fleet.

Family background

Stirling was the fifth of eight sons, ninth of the sixteen children, of Andrew Stirling, Esq. ofDrumpellier

Drumpellier Country Park is a country park situated to the west of Coatbridge, North Lanarkshire, Scotland. The park was formerly a private estate. The land was given over to the Burgh of Coatbridge for use as a public park in 1919, and was desig ...

near Coatbridge

Coatbridge (, ) is a town in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, about east of Glasgow city centre, set in the central Lowlands. Along with neighbouring town Airdrie, North Lanarkshire, Airdrie, Coatbridge forms the area known as the Monklands (popula ...

, North Lanarkshire

North Lanarkshire (; ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It borders the north-east of the Glasgow City council area and contains many of Glasgow's suburbs, commuter towns, and villages. It also borders East Dunbartonshire, Falkirk (co ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and his father's second cousin, Anne Stirling.

The Glaswegian Stirling family was made enormously wealthy by the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

in Britain, and Stirling's father in law James Mangles was a wealthy Atlantic Ocean slaver. The Stirling family were also well-known and celebrated in the naval annals of the 18th century. His maternal grandfather was Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Sir Walter Stirling and his uncle was Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Sir Charles Stirling. With such a family background, it was natural for James to enter the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. His education at Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

was interleaved with periods of training on board British warships, and on 14 January 1804, at the age of 12, he entered the navy as a First-Class Volunteer,Admiralty Service Oof James Stirling, ADM 107/41 embarking on the storeship HMS ''Camel'' for the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. Thus he began a distinguished career.

Early career

Period as a midshipman

Stirling trained for

Stirling trained for midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

on board and also served for a period on under the flag of Admiral Sir John Duckworth, Commander-in-Chief, Jamaica Squadron. He passed his midshipman tests on 20 January 1805 and shortly afterwards was posted to , but on 27 June, at the request of his uncle, Rear-Admiral Charles Stirling

Charles Stirling (28 April 1760 – 7 November 1833) was a vice-admiral in the British Royal Navy.

Early life and career

Charles Stirling was born in London on 28 April 1760 and baptised at St. Albans on 15 May. The son of Admiral Sir Walter ...

, he joined his uncle's flagship, the 98-gun .

The following month, at age 14, he was to see his first naval action. ''Glory'' was in the fleet, commanded by Vice-Admiral Robert Calder

Admiral Sir Robert Calder, 1st Baronet, (2 July 174531 August 1818) was a Royal Navy officer who served in the Seven Years' War, the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. For much of his career he w ...

, which in July that year engaged against the combined French and Spanish fleets off Cape Finisterre

Cape Finisterre (, also ; ; ) is a rock-bound peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain.

In Roman times it was believed to be an end of the known world. The name Finisterre, like that of Finistère in France, derives from the Latin , mean ...

during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. ''Glory'' sustained a damaged foremast spar and sails "much torn". After the battle, the Squadron returned to England with two captured Spanish ships as prizes.

In July 1806 his uncle was given a new ship, , and orders to convoy General Samuel Auchmuty and his troops to the Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (; ), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda, Colonia, Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and ...

and take over command of the squadron there from Admiral Sir Home Popham

Rear-Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham, KCB, KCH (12 October 1762 – 20 September 1820), was a Royal Navy officer and politician who served in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He is known for his scientific accomplishments, particula ...

on the flagship . James accompanied his uncle and saw the fall of Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

to General Auchmuty's forces and the capture of twenty-five warships and more than 10,000 tons of merchant shipping. In August 1807 the Stirlings crossed the South Atlantic for a stay of five months at the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

and at the end of February 1808 ''Diadem'' returned to England via a short period in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

.

On arrival in England in April, Midshipman Stirling was posted to under Captain Henry Blackwood

Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Blackwood, 1st Baronet (28 December 1770 – 13 December 1832), whose burial site and memorial are in Killyleagh Parish Church, was an Irish officer of the British Royal Navy.

Early life

Blackwood was the fourth son of ...

. At this time he was preparing for his examinations to become a lieutenant, and Blackwood arranged for him to have short stints as Acting Lieutenant on other vessels in the Channel Fleet. He started his examinations at Somerset House

Somerset House is a large neoclassical architecture, neoclassical building complex situated on the south side of the Strand, London, Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadran ...

on 1 August 1809 and on 12 August rejoined ''Warspite'' as a full Lieutenant.

West Indies

On 1 April 1810 Stirling was transferred from ''Warspite'' to under Captain R.D. Dunn and moved with Dunn when the Captain was transferred to in November. A year later, on 20 November 1811, he received a significant elevation to flag lieutenant on , the flagship of his uncle, now vice-admiral and commander-in-chief of the Jamaica Station. On 3 March 1812, he was appointed acting commander of the sloop and three months later, at age 21, he was promoted to the rank of commander.Admiralty Service Record, James Stirling, ADM 196/6 Soon after that he was given command of the 28-gun sloop , built in 1808, in which he was to serve for six years. In the

In the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

between the United States of America and Britain, the role assigned to the ships of the Jamaica Station was to attack the US coast and ports on the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

and to destroy their ships and stores. On 11 July 1812 ''Brazen'' weighed anchor on Stirling's first mission, which was to be against New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

and the Mississippi delta. However, ''Brazen'' was severely damaged by a hurricane and had to abandon the mission and enter the Spanish port of Pensacola

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only city in Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Pensacola metropolitan area, which ha ...

to carry out repairs. Despite this, Stirling was able to make a valuable survey of Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. T ...

and the Spanish-held Florida coastline and capture an American ship, which he took back to Jamaica as a prize on 20 November.Brazen's log, ADM 51/2013

He had no immediate opportunity to revisit the Gulf of Mexico, as ''Brazen'' was ordered to return to England for a maintenance survey. After docking in Sheerness for four months, the ship escorted a convoy carrying settlers and stores to Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

. On his return to the Strait of Dover

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, historically known as the Dover Narrows, is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, and separating Great Britain from continental ...

at the end of December 1813, Stirling received confidential orders for an important mission, to carry the Duke of Brunswick

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they a ...

to Holland. After that, during most of 1814, ''Brazen'' patrolled the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

and the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

in search of French or American ships until, at the end of the year, Stirling received orders to return to the West Indies, to the Windward Islands Station at Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, where Admiral Duckworth was now Commander-in-Chief.

There were now two stations in the West Indies, at Barbados and Jamaica, and for a while ''Brazen'' shuttled between the two, carrying communications between the two admirals. On one such trip Stirling was introduced to Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24July 178317December 1830) was a Venezuelan statesman and military officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bol ...

, who was in Jamaica following a defeat on the South American mainland. Soon after that he was given a mission to carry the news of the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, ending the War of 1812, to the British troops under the command of General John Lambert, near New Orleans, and to assist in their return to England. His reconnaissance of Mobile Bay and the coast of Florida three years earlier now stood him in good stead. The troops, who had captured Fort Bowyer

Fort Bowyer was a short-lived earthen and stockade fortification that the United States Army erected in 1813 on Mobile Point, near the mouth of Mobile Bay in what is now Baldwin County, Alabama, but then was part of the Mississippi Territory. Th ...

, were recovered and some of them, under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Harry Smith, were taken to England on ''Brazen'' after surviving a severe gale in the Gulf of Florida. Smith was impressed with Stirling's seamanship and became a long-standing friend.

The Treaty of Paris, signed by France, Great Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia on 20 Nov 1815, ended the Napoleonic Wars and a large fleet was no longer needed. The Admiralty set about decommissioning ships and retiring officers. However, Stirling and ''Brazen'' received a stay of execution, as they were needed again in the West Indies. Spain was losing its grip on the north of South America and rival factions were struggling for power. So close to the West Indies, Britain had an interest in the establishment of secure government on the mainland, but needed to be careful to avoid offending Spain, now an ally. ''Brazen'' arrived at Barbados in June 1816 and on 20 July Stirling and the Barbados Harbourmaster were sent to survey the coast of Venezuela and gain intelligence regarding the attitudes of the population and the disposition of the various revolutionary factions.

After making his report Stirling went back to patrolling the Caribbean with orders to prevent piracy and the contraband trade. Late in September he seized the . This action turned out to be unwise. ''Hércules'', not to be confused with ''Hercule'' on which Stirling had served in 1804, was nicknamed ''Black Frigate'' and had at one time been the flagship of the Argentine Navy. When taken by Stirling, she was a privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

with 22 guns carrying a valuable cargo plundered from Spanish American cities and ships. She was under the command of William Brown, who had been an admiral in the Argentine Navy and was in command of the revolutionary fleet fighting the Spaniards. Her capture compromised the cautious line taken by the British between the Spanish and the revolutionaries. The Governor of Barbados ordered her release, but, when she had left Barbados, Stirling recaptured her and took her to Antigua as a prize. After long drawn-out proceedings, the High Court of the Admiralty ruled in Brown's favour, but he lost the frigate and her cargo. Stirling continued to receive demands for payment of damages for many years.

At the end of 1816 Stirling was commissioned to make a further detailed inspection of the conditions in Venezuela. From Güiria in the

At the end of 1816 Stirling was commissioned to make a further detailed inspection of the conditions in Venezuela. From Güiria in the Paria Peninsula

The Paria Peninsula () is a large peninsula on the Caribbean Sea, in the state of Sucre in northern Venezuela.

Geography

Separating the Caribbean Sea from the Gulf of Paria, the peninsula is part of the mountain range, in the Venezuelan Coa ...

he sailed west to Caracas

Caracas ( , ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas (CCS), is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern p ...

and the port of La Guaira

La Guaira () is the capital city of the Venezuelan Vargas (state), state of the same name (formerly named Vargas) and the country's main port, founded in 1577 as an outlet for nearby Caracas.

The city hosts its own professional baseball team i ...

and returned eastward by an inland route, in order to study the conditions in the interior of the country. In February 1817 he submitted a detailed report to the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral John Harvey John Harvey may refer to:

People Academics

*John Harvey (astrologer) (1564–1592), English astrologer and physician

*John Harvey (architectural historian) (1911–1997), British architectural historian, who wrote on English Gothic architecture a ...

. In it he blamed Spanish neglect for the devastation and decay he found in the interior. He described the insurgent "Patriots" as determined and disciplined, but the Loyalists were indisciplined and lazy. Following this, Stirling was given a number of covert missions in connection with Venezuela. The exact orders he received are not known, as the period from January to June 1817 has been removed from ''Brazen's'' log in Admiralty files. In May, the Executive Committee of the Patriots prepared a draft ''Constitution for the Republic of Venezuela'' which was given to Stirling for transmission to the West Indies Stations and thence to England. However this draft was subsequently rejected by Bolívar. Another source reports that a secret agreement, between the British and the Republicans, was signed later on board ''Brazen'', in which the British would assist Bolívar in exchange for preferential trading rights when the Republic came into being.

In the second half of 1817 Stirling returned once again to patrolling the Caribbean with orders to seize any vessels suspected of piracy, orders which he carried out with alacrity because of the prize money. By June 1818 ''Brazen'' was in need of repair and he returned with her to England, where the ship was taken out of commission and Stirling received the dread news that he was to be placed on half pay. However, Admiral Harvey had sent the Lords of the Admiralty a letter strongly commending "the zeal and alacrity of this intelligent and excellent officer", which may have influenced their decision to promote him to Post Captain on 7 December 1818.

Surrey

Although at the end of 1817 he was not to know it, Stirling was to be without a command for eight years. Between 1818 and 1822 his father, Andrew, was a tenant at Henley Park inSurrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

,

and Stirling made use of his enforced leave to visit his parents and other members of his scattered family. He also made several visits to the Continent of Europe. On one such visit to France he met and befriended Captain James Mangles, RN, who was also on half pay. Mangles was returning from a tour of North Africa and Asia Minor and was among the first Europeans to have visited Petra

Petra (; "Rock"), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu (Nabataean Aramaic, Nabataean: or , *''Raqēmō''), is an ancient city and archaeological site in southern Jordan. Famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit systems, P ...

. His uncle had an estate at Woodbridge Park, about ten miles from the Stirlings at Henley Park and had extensive interests in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

, had been High Sheriff for Surrey in 1808 and was a director of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

.

Captain Mangles invited Stirling to visit Woodbridge, where he met for the first time the, then, 13-year-old Ellen Mangles, his future wife. The two families got on well together and the parents were delighted two years later when, according to the etiquette of that era, Stirling formally asked the uncle's permission to propose marriage to his daughter. The permission was granted on the condition that Stirling should not make the proposal until Ellen completed her schooling.

The couple were married at Stoke Church, Guildford on 3 September 1823, on Ellen's 16th birthday,

and went on a nine-month honeymoon and grand tour. On their return, Ellen gave birth to their first child, Andrew, at Woodbridge on 24 October 1824.

During the next eighteen months Stirling put forward several ideas to the Admiralty, including a means of assessing compass declinations at sea and a proposal for improving stowage in warships. He was keen to keep his name in front of those in the Admiralty who could post him to active service. He had returned from the grand tour short of funds, his father had died in 1823, the family businesses were not prospering and he himself had to make payments to the court in connection with the ''Hércules'' case. The competition for preferment from other officers on half pay was intense, so he was fortunate that on 23 January 1826 he was recommissioned and given command of the newly built .

Australia

In 1826 the western side of Australia was still called New Holland, however the Dutch appeared to have no interest in its development. For the British, a port on the west or north coast might be a useful stage for trade with their settlements in the Cape of Good Hope, India and Singapore. However, the French were known to have an intense interest and French ships were exploring the Australian coasts. The British needed to assess further the potential of the region and find out the extent of the French interest without creating a diplomatic incident. For this task, Stirling, with his record of exploration, diplomacy and covert missions, was a natural choice.New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

was running short of currency and the settlement on Melville Island was short of food and scurvy was rife. A supply mission to these would be excellent cover for intelligence gathering activities.

''Success'' sailed on 9 July 1826, carrying cases of coins and a distinguished passenger, Admiral Sir James Saumarez, Knight Companion of the Bath, a hero of the Napoleonic Wars. Ellen and one year old Andrew remained at home at Woodbridge. One of Stirling's officers was 3rd Lieutenant William Preston, who would marry Ellen's sister Hamilla seven years later. ''Success'' arrived at the Cape of Good Hope on 2 September, discharged its passenger, took on provisions and set sail again, arriving at Sydney Heads

The Sydney Heads (also simply known as the Heads) are a series of headlands that form the wide entrance to Sydney Harbour in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. North Head and Quarantine Head are to the north; South Head and Dunbar Head are to ...

on 28 November.

Captain Jules d'Urville arrived in Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson, commonly known as Sydney Harbour, is a ria, natural harbour on the east coast of Australia, around which Sydney was built. It consists of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove River, Lane ...

on 2 December on the French corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloo ...

''L'Astrolabe''. ''L'Astrolabe'' was on a voyage of exploration, which gave Stirling an opportunity to assess French interest in the region. Stirling and d'Urville dined together several times and Stirling discovered that ''Astrolabe'' had a detailed chart of the Swan River. Before leaving England, Stirling had studied the available charts of the west coast of Australia and had concluded that the Swan was a possible site for a harbour and settlement and had hoped to be the first European to explore and chart it. However, d'Urville indicated that the French did not consider that the Swan would be a suitable site for a harbour, because of the difficulty of access and lack of fresh water. This gave Stirling a free hand.

A ship arrived from Melville Island on the same day as ''L'Astrolabe'', bringing reassuring news that scurvy was under control and the settlement was progressing more satisfactorily. The Governor, Major General Ralph Darling

General Sir Ralph Darling, GCH (1772 – 2 April 1858) was a British Army officer who served as Governor of New South Wales from 1825 to 1831. His period of governorship was unpopular, with Darling being broadly regarded as a tyrant. He introd ...

, advised Stirling to delay his visit to Melville until later in the year. Stirling then made a report to Darling, setting out detailed arguments for a mission to the Swan River. Darling gave his approval and, on 17 January 1827, ''Success'' sailed from Sydney for the Swan, via Hobart

Hobart ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the island state of Tasmania, Australia. Located in Tasmania's south-east on the estuary of the River Derwent, it is the southernmost capital city in Australia. Despite containing nearly hal ...

in Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

, where several cases of coins were delivered. On board ''Success'' were the Colonial Botanist Charles Frazer, the surgeon Frederick Clause and the landscape artist Frederick Garling.

Swan River exploration

The Nyoongar people call the river Derbarl Yerrigan.

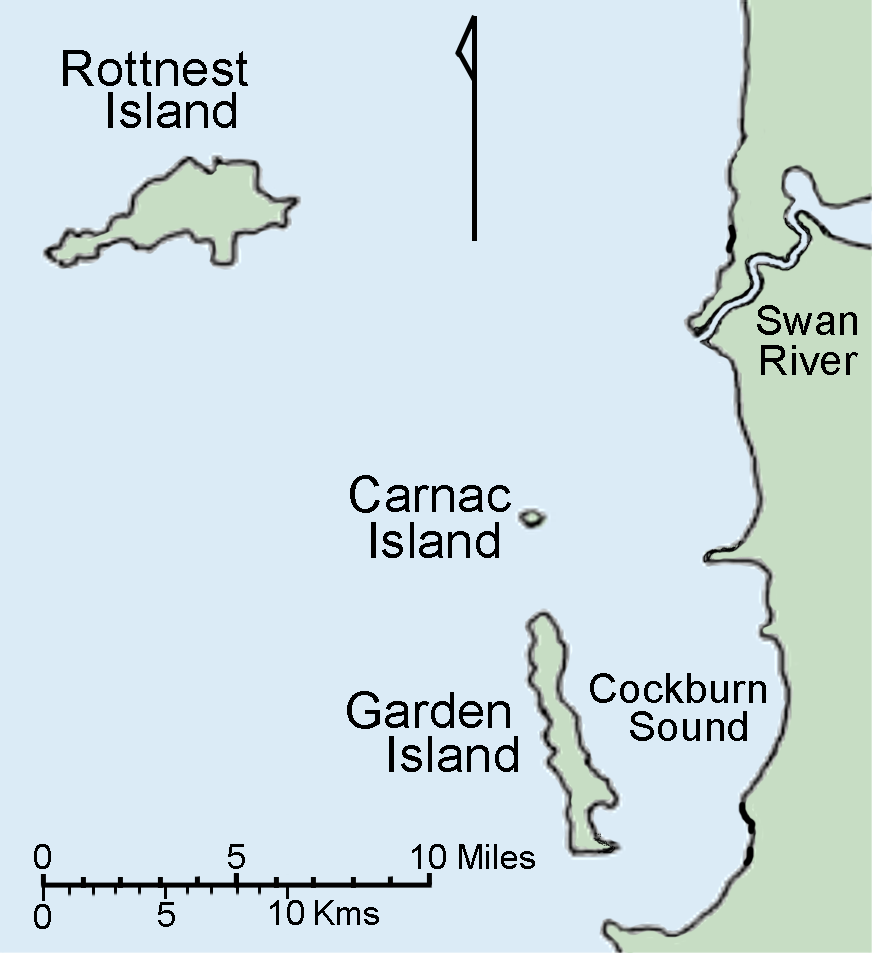

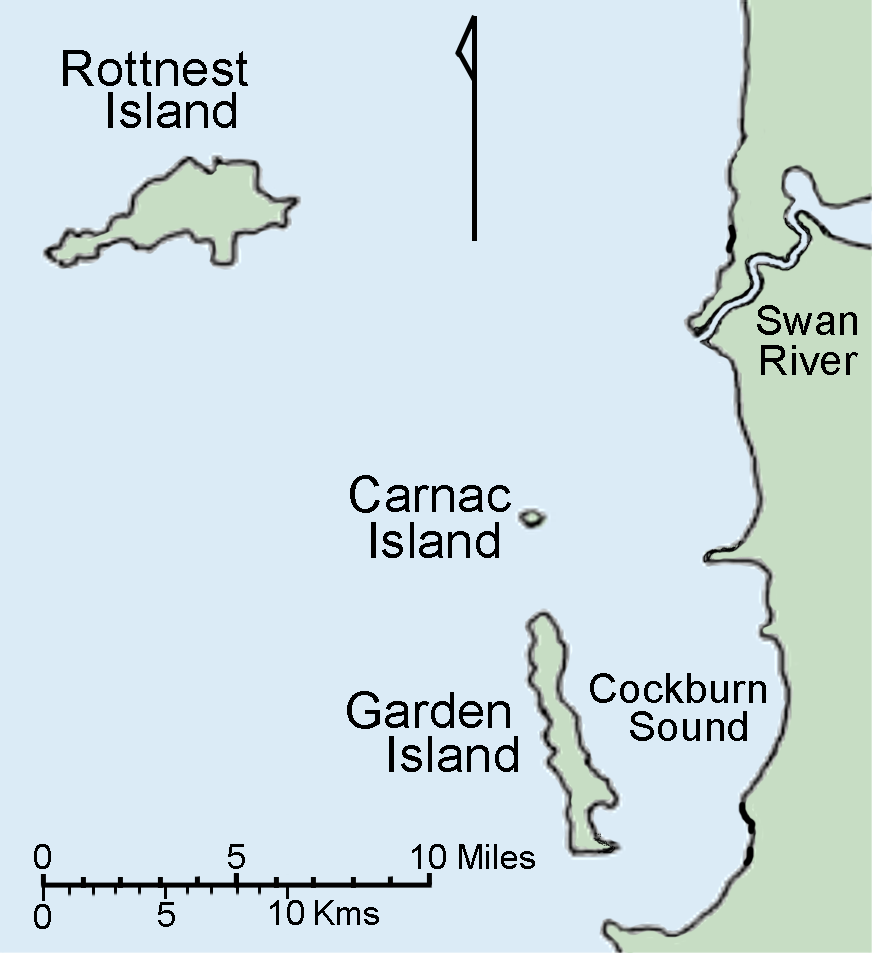

On 10 January 1697, the Dutch sea captain Willem De Vlamingh renamed it to the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large number of black swans they observed there. One hundred and thirty years later, the British ship ''Success'' arrived off the west coast of Australia on 5 March 1827 and anchored near the north east corner of Rottnest Island. The following day, the ship moved cautiously towards the coast and anchored about a mile from the mouth of the Swan. Lieutenant

The Nyoongar people call the river Derbarl Yerrigan.

On 10 January 1697, the Dutch sea captain Willem De Vlamingh renamed it to the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large number of black swans they observed there. One hundred and thirty years later, the British ship ''Success'' arrived off the west coast of Australia on 5 March 1827 and anchored near the north east corner of Rottnest Island. The following day, the ship moved cautiously towards the coast and anchored about a mile from the mouth of the Swan. Lieutenant Carnac

Carnac (; , ) is a commune beside the Gulf of Morbihan on the south coast of Brittany in the Morbihan department in north-western France.

Its inhabitants are called ''Carnacois'' in French. Carnac is renowned for the Carnac stones – on ...

and the ship's Master, Millroy, were left to take soundings and look for channels and possible landing places. Meanwhile, Stirling, Frazer and Lieutenant Preston made a preliminary reconnaissance up the river in the gig. They sailed about five miles upstream, reaching a wide section which Stirling named ''Melville Water''. Other features were named after Stirling's brother Walter and Lieutenant Preston. During the next day more soundings were taken, and ''Isle Berthelot'' and ''Isle Buache'' were renamed ''Carnac Island'' and ''Garden Island''. Stirling gave the name ''Cockburn Sound'' to the "Magnificent Sound between that Island and the Main possessing great attractions for a Sailor in search of a Port".Captain Stirling to Governor Darling 18 April 1827

At mid-day on 8 March the exploration party - Stirling, Frazer, Garling, Clause, Lieutenant Belches, Midshipman Heathcote, the ship's clerk Augustus Gilbert, 7 seamen and 4 marines - left ''Success'' in the cutter and the gig and sailed to ''Point Belches''. There the boats grounded and, as the party was unable to find a channel, the boats were unloaded and dragged across the shallows until nightfall. While this was being done, Stirling, Frazer and Garling climbed the commanding hill on the west bank, which Stirling named ''Mount Eliza'' in honour of Eliza Darling

Eliza, Lady Darling (1798–1868), born Elizabeth Dumaresq, was a British philanthropist and artist. She was the wife of Sir Ralph Darling, Governor of New South Wales from 1825 to 1831.

Early life

She was the daughter of Lieut.-Col. John Dumar ...

, the New South Wales Governor's wife. While there, Garling painted a watercolour landscape view showing the entrance to the river on the opposite side of Melville Water. Stirling later named this ''Canning River'' after the British Prime Minister at that time.

The next day, dragging across the shallows started at daybreak and continued until nightfall. Frazer, exploring on land, found a freshwater brook and Stirling named the nearby point of land ''Point Frazer''. Frazer also found a lagoon of fresh water and the party moved camp to beside it. On the following morning three armed Aboriginal warriors demonstrated their anger at the "invasion" (Stirling's word) of their territory with violent gestures, but eventually retired. During the day, the boats reached the Heirisson Islands and in the channel above them progress was much easier, but still slow, due to the winding of the river. On 11 March the boats passed through a long narrow stretch and encountered more Aboriginal people who threatened the boats with their spears from higher ground. When the boats reached more level terrain, gestures of goodwill defused the situation and the Aboriginals moved on.

On 12 March the boats reached a place where a tributary, later named ''

The next day, dragging across the shallows started at daybreak and continued until nightfall. Frazer, exploring on land, found a freshwater brook and Stirling named the nearby point of land ''Point Frazer''. Frazer also found a lagoon of fresh water and the party moved camp to beside it. On the following morning three armed Aboriginal warriors demonstrated their anger at the "invasion" (Stirling's word) of their territory with violent gestures, but eventually retired. During the day, the boats reached the Heirisson Islands and in the channel above them progress was much easier, but still slow, due to the winding of the river. On 11 March the boats passed through a long narrow stretch and encountered more Aboriginal people who threatened the boats with their spears from higher ground. When the boats reached more level terrain, gestures of goodwill defused the situation and the Aboriginals moved on.

On 12 March the boats reached a place where a tributary, later named ''Helena River

The Helena River is a tributary of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in Western Australia. The river rises in country east of Mount Dale and flows north-west to Mundaring Weir, Western Australia, Mundaring Weir, where it is dammed. ...

'', joined the Swan from the east. The party also found another fresh water stream, which they named ''Success'', on the west side of the Swan. From this point on, the Swan narrowed and there were many obstructions. The next day, the cutter

Cutter may refer to:

Tools

* Bolt cutter

* Box cutter

* Cigar cutter

* Cookie cutter

* Cutter (hydraulic rescue tool)

* Glass cutter

* Meat cutter

* Milling cutter

* Paper cutter

* Pizza cutter

* Side cutter

People

* Cutter (surname)

* Cutt ...

was holed and had to be repaired, after which the party reached a creek which Stirling named ''Ellen Brook'', after his young wife. The Swan was not navigable any further and Stirling and Garling set off on foot for the hills to the east, arriving at about sunset. On their return to camp they lost their way in the dark, but Frazer sent out search parties to guide them back. On 14 March the party split into three groups. Frazer went east and Belches and Heathcote north. Stirling and Clause went west and discovered a freshwater lagoon, some Aboriginal huts and a fertile region which so pleased Stirling that he named it ''Henley Park'' after his Surrey home.

The return journey was much quicker, being downstream and through previously charted areas. On arrival at Melville Water, Belches was sent to explore the Canning River. The rest of the party returned to ''Success'' and spent the next four days surveying the surrounding islands and finding a safe channel into Cockburn Sound. On 21 March ''Success'' weighed anchor and three days later arrived at Geographe Bay

Geographe Bay is in the south-west of Western Australia, around southwest of Perth.

The bay was named in May 1801 by French explorer Nicolas Baudin, after his ship, ''Géographe''. It is a wide curve of coastline extending from Cape Natur ...

, in order to carry out Governor Darling's instructions to explore and report on the region. Geographe Bay was named in May 1801 by French explorer Nicolas Baudin. ''Success'' then sailed to King George Sound

King George Sound (Mineng ) is a sound (geography), sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came in ...

, to pick up Major Edmund Lockyer and unload provisions for the settlement there, after which the ship returned to New South Wales, anchoring off Sydney Heads on 16 April.

Stirling's report to Darling and Frazer's report on the quality of the land were enclosed with Darlings report of 21 April 1827 to the Colonial Office in the United Kingdom. Stirling's report consisted of a diary ''Narrative of Operations'' and a section ''Observations on the Territory'', which included a report by Clause on the healthiness of the climate. Later events showed that all three reports were over enthusiastic, the party having explored only the strip of soil in the vicinity of the Swan. Frazer was heavily criticised for this later. However, in their defence, both Clause and Frazer were subject to Stirling's intense enthusiasm for the project and may have been unduly influenced by it. Stirling wrote a second report on the Swan River on 31 August. This was addressed to the Admiralty and was shorter, placing more emphasis on naval concerns and the strategic value of the area.

Melville Island and North Australia

Stirling's original mission included a task to carry supplies to Melville Island. However, Darling had received further instructions to investigate the formation of a new settlement on the coast to the east of Melville Island.NSW State Record

Stirling's original mission included a task to carry supplies to Melville Island. However, Darling had received further instructions to investigate the formation of a new settlement on the coast to the east of Melville Island.NSW State RecordArchives

/ref> Accordingly, ''Success'' left Sydney on 19 May 1827 carrying an establishment force for a new settlement and accompanied by the brig ''Mary Elizabeth''. The two ships separated. ''Mary Elizabeth'' sailed to Melville Island and on 15 June ''Success'' anchored in Palm Bay, on the western side of Croker Island. Stirling quickly established that the island was unsuitable for settlement and sent a boat across to the mainland to explore Raffles Bay. The report being favourable, Stirling looked no further and on 18 June he went ashore with his officers to take possession of Raffles Bay and the surrounding territory in His Majesty's name. The establishment force and supplies were landed and Stirling named the settlement Fort Wellington, Australia, Fort Wellington. A month later, believing all to be well, Stirling set sail for Melville island. ''Success'' arrived at History of the Northern Territory#European exploration and settlement, Fort Dundas on Melville Island on 25 July and set sail again four days later for Madras, and then to Penang, to report to William Hall Gage, Admiral Gage, Commander of the Eastern Station. Stirling was keen to return home to see his family and to further his case for a settlement at the Swan River. However, Gage instructed him to base ''Success'' in Trincomalee Harbour, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where he arrived on 4 January 1828. There he succumbed rapidly to the tropical climate and on 21 February three Royal Navy surgeons certified that he was so ill he should return immediately to England. The settlements at Fort Dundas and Fort Wellington rapidly got into difficulties with outbreaks of scurvy and fever, supply shortages and communication failures. The Melville Island outpost was abandoned in November 1828 and the Raffles Bay settlement was broken up in July 1829.

Western Australia

On returning to London in 1828, Stirling lobbied the Foreign Office and the Admiralty for support for a settlement in the vicinity of the Swan River, describing it as ideal for a permanent establishment. He emphasised the defensive prospects of Mount Eliza, Western Australia, Mount Eliza, the large hill on which Kings Park, Western Australia, Kings Park is now situated, "as it is near the narrows of the Swan River, which would make defending the colony from gunships easy, with just a few cannons." On 21 August 1828, Stirling and his friend the colonial expert Thomas Moody (1779-1849), Thomas Moody wrote to Under-Secretary Robert Hay to offer to form an association of private capitalists to using their own money settle Australia in fulfilment of the "principles" of William Penn's settlement of Pennsylvania. Moody was endorsed by the Tories (British political party), Tories in Parliament of the United Kingdom, Parliament, who had recently commended his report to Parliament on slavery. Moody had previously advised Stirling's relation James Mangles (Royal Navy officer), James Mangles about the settlement of theSwan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just ''Swan River'', was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, an ...

at minimal cost to the British Government.

Parliament initially rejected the proposal of Stirling and Moody, but rumours of a new French interest in the region provoked George Murray (British Army officer), Sir George Murray, on 5 November, to request that the Admiralty send a ship-of-war "to proceed to the Western Coast of New Holland and take possession of the whole territory in His Majesty's name." This task was given to under the command of Captain Charles Fremantle and, a week later, a further order was issued to prepare to carry a detachment of troops to the Swan River.

On 31 December Murray wrote to Stirling confirming his title as Lieutenant-Governor of the new colony and on the same day his Under-Secretary, Robert Hay, confirmed the appointment of the members of the civil establishment including Colonial Secretary Peter Broun, Peter Brown, Surveyor-General John Septimus Roe

John Septimus Roe (8 May 1797 – 28 May 1878) was the first Surveyor-General of Western Australia. He was a renowned explorer, a member of Western Australia's legislative and executive councils for nearly 40 years, but also a participant in ...

, Harbourmaster Mark John Currie, naturalist James Drummond (botanist), James Drummond, a surgeon, a storekeeper, a cooper, a blacksmith and a boatbuilder. After hectic preparations, on 6 February 1829 these pioneers, with their assistants, families, servants and livestock, departed Plymouth in ''Parmelia (barque), Parmelia'' under Captain J H Luscombe out of Spithead in company with ''Sulphur'', carrying 100 men of the 63rd Regiment of Foot, under the command of Major Frederick Irwin, and three years' of army stores, 10,000 bricks and £1,000 to meet all expenses of government.

On arrival on 31 May at Garden Island (Western Australia), Garden Island, at what became known as the Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just ''Swan River'', was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, an ...

, they re-erected a wooden house that had first been assembled at Lieutenant Preston's home in Sutton Green, Surrey, that would become the Governor's home. These pioneers were responsible for laying the foundations of Perth, Western Australia, Perth, Fremantle, Western Australia, Fremantle and the market-town named Guildford, Western Australia, Guildford that is now a suburb of Perth.Christopher John Pettitt, ''Normandy Historians section of the Normandy & Worplesdon Directory'', page 33, January 2008

Stirling administered the Swan River settlement from June 1829 until 11 August 1832, when he left on an extended visit to England where he was knighted, and again from August 1834 until December 1838. However, he was commissioned as Governor of Western Australia only from 6 February 1832, rectifying the absence of a legal instrument providing the authority detailed in Stirling's Instructions of 30 December 1828. Stirling had said I believe I am the first Governor who ever formed a settlement without Commission, Laws, Instructions and Salary.With the creation of the Western Australian Legislative Council in 1830, Stirling automatically became an official member. In October 1834 Stirling led a detachment of 25 armed troopers and settlers including Septimus Roe and Thomas Peel that attacked an encampment of 60-80 Pindjarep Aboriginal people. The Pindjarep fled into the bush and were later encircled near a crossing on the

Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray; Ngarrindjeri language, Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta language, Yorta Yorta: ''Dhungala'' or ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is List of rivers of Australia, Aust ...

at Pinjarra, Stirling referred to this as the Battle of Pinjarra. Settlers accounts claim between 10 and 80 Aboriginal people died, compared to Aboriginal oral history which claim 150 people died.

Stirling remained entirely unsympathetic to the needs of Aboriginal people in Western Australia, and never recognised their prior ownership of the land despite the fact that the Buxton Committee of the British House of Commons informed him that this was a mistake for which the new colony would suffer. Stirling mentioned in dispatches that the Aborigines "must gradually disappear" and the "most anxious and judicious measures of the local government [could] prevent the ulterior extinction of the race".

As recognition of his service in establishing the colony Stirling was granted land near Beverley, Western Australia. This land, along with neighbouring properties was re-acquired by the Western Australian Government, who later subdivided the land into farmlets for returning soldiers. The remaining land was later used to establish the Avondale Agricultural Research Station, which includes Stirling's restored homestead.

Harvey

In 1829 Stirling selected of land in Harvey, Western Australia, Harvey and called it the "Harvey River Settlement". However, the only improvement made was a convict built cottage on the banks of the Harvey River. The cottage featured a shingled roof and pit-sawn jarrah walls with hexagonal-shaped paving blocks fitted together to form firm flooring. A replica cottage known as Stirling's Cottage has been built on the site and includes one of the original paving blocks in its history room.Mediterranean and west coast of Europe

HMS ''Indus''

In 1840 Stirling was given command of and instructions to join the Mediterranean Fleet. The British Foreign Secretary, Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, Lord Palmerston, considered it was necessary to show a strong British naval presence in the Mediterranean. Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha had triggered the Oriental Crisis of 1840 by declaring himself Khedive of Egypt, which had been until then a province of the Ottoman Empire. Also King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies and Naples, had been persuaded by a British naval blockade of Naples to restore to a British company the monopoly for Sicilian Sulfur#History, sulphur, an essential ingredient of gunpowder. ''Indus'' reached Gibraltar in August 1841 and made herself felt along the Algerian coast on her way to the Mediterranean station at Malta.Indus log, 1840-44, ADM 51/3616 For a few months she was deployed around Sicily and the boot of Italy, but in November Stirling received new instructions to show a presence and monitor the situation at Lisbon. Portugal had been in turmoil for several years and the British Admiralty had received intelligence that Lisbon was threatened by a 5,000 strong revolutionary army and the Portuguese Government was preparing for conflict. Stirling was directed not to take part in any action, but to safeguard British subjects and the Portuguese royal family. In the event, the conflict was resolved peacefully. In June ''Indus'' was ordered back to Malta and then to Smyrna, where there had been an insurrection and British subjects and property in the region were thought to be at risk. This threat also failed to materialise and after three months at Piraeus in Greece ''Indus'' sailed to Naples to take part in the farewell celebrations sending the Princess Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies, Teresa Cristina on her way to marry the Emperor Pedro II of Brazil. This was a major diplomatic event and Stirling entertained the British Ambassador and British Consul on board and was received by King Ferdinand. The harbour was filled with vessels of the Neapolitan, Brazilian and British navies as well as an American warship and Stirling sent a detailed report on the foreign warships to the Admiralty. A brief spell at Gibraltar was followed by a visit to Cadiz to prevent a planned blockade of the harbour by rebel troops. Then, in September 1843, Vice-Admiral Sir Edward Owen (Royal Navy officer), Edward Owen, Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet, received an urgent request for assistance from Sir Edmund Lyons, 1st Baron Lyons, Edmund Lyons, the British Consul in Athens. King Otto of Greece had rejected a proposed new constitutional government for Greece and was facing an armed rebellion. Stirling was to join , under the command of Sullivan Baronets, Sir Charles Sullivan, place himself at the disposal of Sir Edmund and arrange for the protection of British subjects. Stirling's charm and diplomatic skill, combined with the presence of three British warships in the harbour, calmed the situation and, despite the King's reluctance to adopt the new constitution, Sullivan and Stirling persuaded him that acceptance was the wisest course. In gratitude for their help in quelling the rebellion and negotiating with his ministers, the King bestowed on Sullivan and Stirling Greece's high honour, Knight Commander of the Order of the Redeemer. Following this, Stirling returned to England, where ''Indus'' was paid off on 13 June 1844.HMS ''Howe''

Stirling received his fourth command, the 120-gun first rate ship of the line in May 1847 and joined the Channel Fleet under the command of the newly appointed Rear-Admiral Charles John Napier, Sir Charles Napier on .Howe log, 1847, ADM53/2694 In September he received special orders. He was to conduct Her Majesty, the DowagerQueen Adelaide

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen (Adelaide Amelia Louise Theresa Caroline; 13 August 1792 – 2 December 1849) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Queen of Hanover from 26 June 1830 to 20 June 1837 as the wife of King W ...

, Queen Victoria's aunt, on trips to Lisbon and Madeira and then back to Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house in the style ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

. Flying the Royal Standard at the main, ''Howe'' entered the River Tagus on 22 October. Sir Charles Napier immediately boarded to pay his respects, followed shortly afterwards by Ferdinand II of Portugal, Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg Gotha, King of Portugal, and two princes. The next day, all the captains in the squadron donned full dress and white trousers and were formally presented to the Dowager Queen, after which Napier and Stirling escorted her to the royal Palace of Necessidades, where they were received by Maria II of Portugal, Queen Maria II.

After five days of sightseeing, the party set sail for Madeira. Leaving the Tagus, ''Howe'' was struck by a large wave and the Queen slipped and nearly fell overboard, but was saved by Stirling, who in so doing lost his ceremonial sword overboard. The grateful Queen later presented him with a magnificent replacement, a fine gold plated dress sword and scabbard which had been specially made for her. She also presented him with a silver snuff box with an inscription thanking him for his presence of mind on the occasion. After delivering the Queen in Madeira, ''Howe'' returned to Lisbon and took part in various exercises and manoeuvres before leaving again to collect her for the return voyage. She arrived at Osborne House on 27 April and Stirling learned a year later that she had honoured him by appointing him as her naval aide-de-camp.

He now had a few weeks with his family before receiving orders to report at Malta to Vice-Admiral Sir William Parker, 1st Baronet, of Shenstone, Sir William Parker, Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet, who had succeeded Sir Edward Owen. During the next few years, the presence of the British and French fleets encouraged an uneasy peace in the eastern Mediterranean. In 1849 ''Howe'' was recalled. She reached England on 2 July and two weeks later the ship's company was paid off.

Far East

In July 1851, Stirling was promoted to rear admiral and in the following year served as Third Sea Lord, Third Naval Lord at the British Admiralty, Admiralty. From January 1854 to February 1856 Stirling was commander in chief of theEast Indies and China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, East Indies and China was a formation of the Royal Navy from 1831 to 1865. Its naval area of responsibility was the Indian Ocean and the coasts of China and its navigable rivers.

The Commander-in-Chief was appointed in 18 ...

. Using gunboat diplomacy

Gunboat diplomacy is the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to the superior force.

The term originated in ...

he signed the first British treaty with Japan (the Anglo-Japanese Friendship Treaty

The was the first treaty between the United Kingdom and Japan, then under the administration of the Tokugawa shogunate. Signed on October 14, 1854, it paralleled the Convention of Kanagawa, a similar agreement between Japan and the United States s ...

) on 14 October 1854.

In November 1854, with Hong Kong Governor John Bowring, he led a fleet up the Pearl River (China), Pearl River to Guangzhou, Canton to support the Viceroy of Liangguang (modern day Guangdong and Guangxi) Ye Mingchen and his forces besieged by the Tiandihui army. The fleet carried weapons and ammunition, food and Qing Dynasty, Qing reinforcements.

Retirement

Stirling was promoted vice admiral in August 1857. He became an admiral in November 1862 and died in comfortable retirement at his home in Woodbridge Park, near Guildford in Surrey, on 22 April 1865 aged 74. There is a memorial tablet within St Marks Church, Wyke, Surrey, Wyke. Ellen survived him by nine years. Stirling and his wife were buried in the extension to the graveyard of St John's Church on Stoke Road, near Guildford where they had been married.Honours

The plant genus ''Stirlingia'', was named in his honour by Stephan Endlicher in 1838. A variety of Pittosporum is also named in his honour. In England, Stoke Church's social centre and hall is named ''The Stirling Centre''. In Western Australia the suburb of Stirling, Western Australia, Stirling is named after him, as is Division of Stirling, a seat in the lower House of the federal Parliament and Governor Stirling Senior High School. The Royal Australian Navy's Indian Ocean Fleet is based at HMAS Stirling, near Rockingham, Western Australia, Rockingham. Stirling Highway (which links Perth and Fremantle) was named so in his honour. There are also many buildings and businesses named after him throughout Perth and Fremantle.Dishonours

Following the well-conceived ambush leading to a massacre lasting at least one hour and now known as the Pinjarra massacre, Pinjarra Massacre that Stirling led personally, Stirling threatened the Noongar people with genocide should they continue to resist colonisation. Given historical records of his involvement, In 2020 a statue of Stirling on Hay Street, Perth, Hay Street in Perth's central business district was Defacement (vandalism), defaced amid Black Lives Matter protests. The statue had its neck and hands painted red, and the Australian Aboriginal flag was painted over the plaque on the ground in front of the statue. Increasingly there are efforts to remove Stirling's name from Western Australian landmarks. In 2019, a petition to rename Stirling Highway received little support. In 2021, "residents at a [City of] Stirling council electors meeting voted in favour of changing their local government's name", although the city "eventually passed a motion that made no mention of any name change", with one councillor saying "while nobody condoned historical atrocities, a name change would cost 'millions of dollars', would set a dangerous precedent and should be 'nipped in the bud." However, shortly afterwards, Western Australian senators called for a broader review of Western Australian "place names, such as Stirling Range, linked to colonial figures with known racism, racist histories ... such as William Dampier, John Forrest andJohn Septimus Roe

John Septimus Roe (8 May 1797 – 28 May 1878) was the first Surveyor-General of Western Australia. He was a renowned explorer, a member of Western Australia's legislative and executive councils for nearly 40 years, but also a participant in ...

."

See also

* History of Western Australia *''Historical Records of Australia'' * Anglo-Japanese relations *References

Further reading

* Hasluck, Alexandra.''James Stirling''. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. 1963. * Statham-Drew, Pamela. ''James Stirling : Admiral and Founding Governor of Western Australia'' : University of Western Australia Press, Crawley W.A., 2003. *External links

Celebrate W.A. site

* *

by Christopher John Pettitt for Normandy Historians , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stirling, James 1791 births 1865 deaths People from North Lanarkshire Clan Stirling, James Explorers of Australia Governors of Western Australia Aboriginal genocide perpetrators Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Western Australian Legislative Council Royal Navy admirals Scottish mass murderers Scottish murderers of children Scottish politicians Japan–United Kingdom relations Settlers of Western Australia Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars People from Coatbridge 19th-century Australian politicians Australian city founders