Caprella mutica on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Caprella mutica'', commonly known as the Japanese skeleton shrimp, is a

Like other

Like other

Males exhibit

Males exhibit

''Caprella mutica'' are native to the subarctic regions of the Sea of Japan in northwestern Asia. They were first discovered in the Peter the Great Gulf in the

''Caprella mutica'' are native to the subarctic regions of the Sea of Japan in northwestern Asia. They were first discovered in the Peter the Great Gulf in the

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of skeleton shrimp

Caprellidae is a family of amphipods commonly known as skeleton shrimps. Their common name denotes the threadlike slender body which allows them to virtually disappear among the fine filaments of seaweed, hydroids and bryozoans. They are sometime ...

. They are relatively large caprellids, reaching a maximum length of . They are sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, with the males usually being much larger than the females. They are characterized by their "hairy" first and second thoracic

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main ...

segments and the rows of spines on their bodies. Body color ranges from green to red to blue, depending on the environment. They are omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize ...

highly adaptable opportunistic feeders. In turn, they provide a valuable food source for fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura (meaning "short tailed" in Greek language, Greek), which typically have a very short projecting tail-like abdomen#Arthropoda, abdomen, usually hidden entirely under the Thorax (arthropo ...

s, and other larger predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s. They are usually found in dense colonies attached to submerged man-made structures, floating seaweed

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), '' Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ''Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as ...

, and other organisms.

''C. mutica'' are native

Native may refer to:

People

* '' Jus sanguinis'', nationality by blood

* '' Jus soli'', nationality by location of birth

* Indigenous peoples, peoples with a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory

** Nat ...

to shallow protected bodies of water in the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it ...

. In as little as 40 years, they have become an invasive species

An invasive species is an introduced species that harms its new environment. Invasive species adversely affect habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term can also be used for native spec ...

in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

, North Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

, and along the coasts of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. They are believed to have been accidentally introduced to these areas through the global maritime traffic and aquaculture. Outside of their native range, ''C. mutica'' are often exclusively synanthropic

A synanthrope (from ancient Greek σύν ''sýn'' "together, with" and ἄνθρωπος ''ánthrōpos'' "man") is an organism that evolved to live near humans and benefit from human settlements and their environmental modifications (see also ...

, being found in large numbers in and around areas of human activity. Their ecological and economic impact as an invasive species is unknown, but they pose a serious threat to native populations of skeleton shrimp in the affected areas.

Description

Like all caprellidamphipod

Amphipoda () is an order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphipod species cur ...

s, ''Caprella mutica'' are characterized by slender bodies and elongated appendages. Their skeletal appearance gives rise to the common names of "skeleton shrimp

Caprellidae is a family of amphipods commonly known as skeleton shrimps. Their common name denotes the threadlike slender body which allows them to virtually disappear among the fine filaments of seaweed, hydroids and bryozoans. They are sometime ...

" or "ghost shrimp", and, coupled with their distinctive upright feeding posture, give them a striking resemblance to stick insect

The Phasmatodea (also known as Phasmida or Phasmatoptera) are an order of insects whose members are variously known as stick insects, stick bugs, walkingsticks, stick animals, or bug sticks. They are also occasionally referred to as Devil's da ...

s and "starved praying mantis

Mantises are an order (Mantodea) of insects that contains over 2,400 species in about 460 genera in 33 families. The largest family is the Mantidae ("mantids"). Mantises are distributed worldwide in temperate ...

es". ''C. mutica'' vary in coloration from translucent pale green, brown, cream, orange, deep red, purple, and even turquoise, depending on the substrate they are found in. The brood pouches of the females are speckled with red spots. A relatively large amphipod, ''C. mutica'' are sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

with males considerably larger than females. Males average at a length of , though specimens have been recorded to reach in length. Females, on the other hand, average at only long.

The body can be divided into three parts – the cephalon

Cephalon, Inc. was an American biopharmaceutical company co-founded in 1987 by pharmacologist Frank Baldino Jr., Frank Baldino, Jr., neuroscientist Michael Lewis, and organic chemist James C. Kauer—all three former scientists with the DuPont ...

(head), the pereon (thorax), and the abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

. The pereon comprises most of the length of the body. It is divided into seven segments known as pereonites. The rounded and smooth cephalon is fused to the first pereonite; while the highly reduced and almost invisible abdomen is attached to the posterior of the seventh pereonite. In males the first two pereonites are elongated, with the second pereonite being the longest of all the pereonites. They are densely covered with long setae

In biology, setae (; seta ; ) are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Depending partly on their form and function, protostome setae may be called macrotrichia, chaetae ...

(bristles), giving them a hairy appearance. The second pereonite also has two to three pairs of spines on the back, with an additional two pairs at the sides near the base of the limbs. The remaining pereonites (third to seventh) lack the dense setae of the first two pereonites. The third pereonite has seven pairs of spines at the back while the fourth pereonite has eight pairs. Both have three to seven pairs of spines near the base of the gills. The fifth pereonite has five pairs of back spines and a pair of spines at the sides. The sixth and seventh pereonites each have two pairs of back spines, situated at their centers and near the posterior. Females differ from males in having much shorter pereonites which lack the dense covering of setae. The cephalon and first pereonite also possess a single pair of spines each, though they can sometimes be absent.

Like other

Like other crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, ''C. mutica'' possess two pairs of antennae, with the first (outer) pair more than half the total length of the body. The segments of the peduncles (base) are three times as long as the flagellae ("whips" at the ends of the antennae). The flagellae have 22 segments each. The second (inner) pair of antennae are less than half the length of the first. They possess two rows of long setae on the ventral surfaces of the segments of their peduncles. Mandibles

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

and maxillae

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxillar ...

are present at the anterior ventral surface of the cephalon. Maxilliped

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part or natural prolongation that protrudes from an organism's body such as an arm or a leg. Protrusions from single-celled bacteria and archaea are known as cell-surface appendages or surface app ...

s, a modified pair of appendages, also serve as accessory mouthparts.

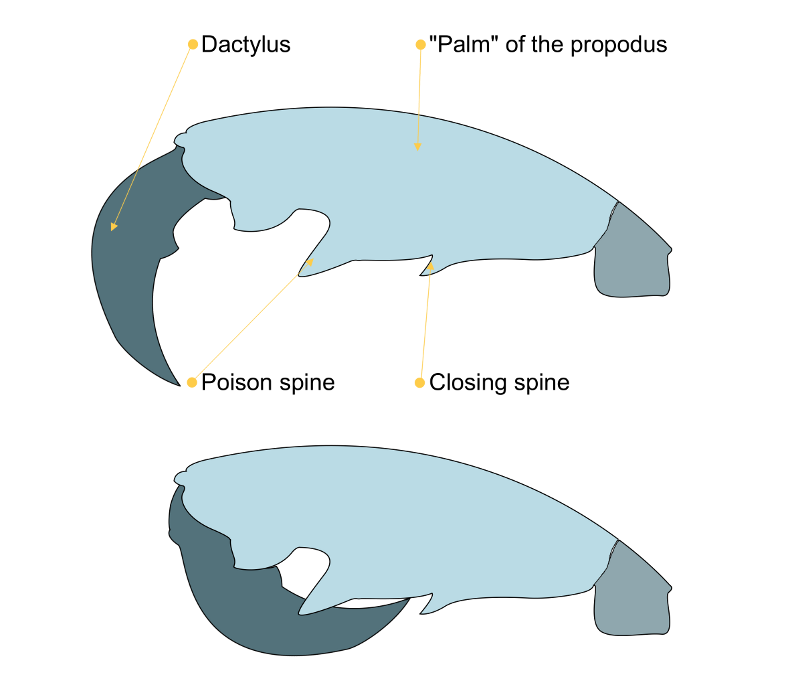

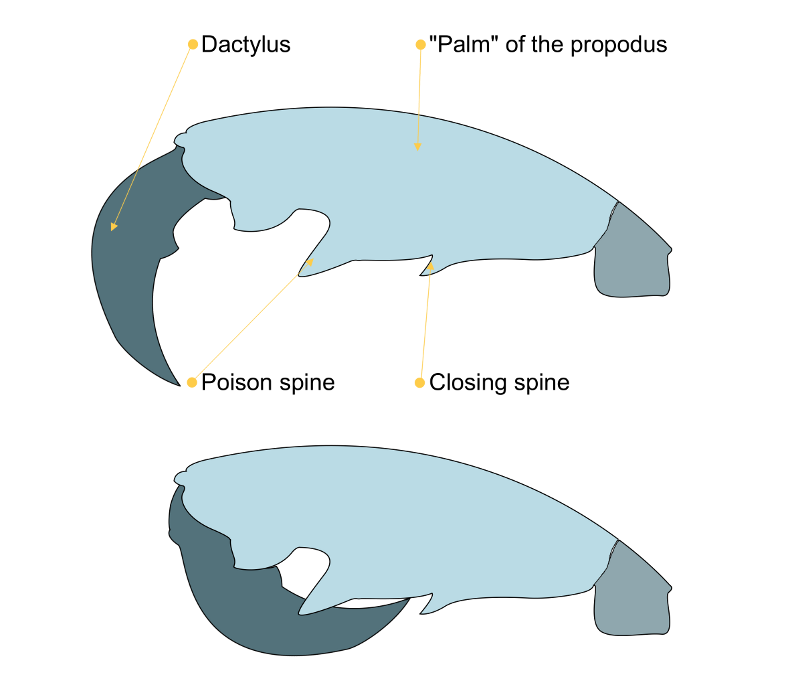

The appendages that arise from pereonites are known as pereopods. The first two pairs of pereopods are highly modified raptorial

In biology (specifically the anatomy of arthropods), the term ''raptorial'' implies much the same as ''predatory'' but most often refers to modifications of an arthropod leg, arthropod's foreleg that make it function for the grasping of prey whi ...

grasping appendages known as gnathopods. They somewhat resemble the arms of praying mantises. The segments of the gnathopods can be divided into two parts which fold into each other: the propodus (plural: propodi, "forelimb") and, at the tip, the dactylus (plural: dactyli, "finger"). The first pair of gnathopods are considerably smaller than the second pair and arise close to the maxillipeds. The inside margins of the propodi possess two spines. Both the propodi and dactyli have serrated inner edges. The second pair of gnathopods are very large with two large spines on the middle and upper edges of the inside margin of the palm of the propodi. The upper spine is known as the "poison spine" or "poison tooth" and may be of the same size or much larger than the lower spine (the "closing spine"). Despite the name, it remains unclear if the poison spine is indeed venomous

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

, though they are perfectly capable of inflicting potentially lethal injuries on small organisms. Recent studies have associated the spines with pores that lead to possible toxin-producing glands.

Their dactyli are powerful and curved into a scimitar

A scimitar ( or ) is a single-edged sword with a convex curved blade of about 75 to 90 cm (30 to 36 inches) associated with Middle Eastern, South Asian, or North African cultures. A European term, ''scimitar'' does not refer to one specific swor ...

-like shape. The second pair of gnathopods are densely covered in hair-like setae while the first pair only has setae on the posterior margins. The third and fourth pereopods are absent. In their place are two pairs of elongated oval gills arising from the third and fourth pereonites, respectively. In mature females, two brood pouches also develop in the third and fourth pereonites. These are formed by oostegites – platelike expansions from the basal segments ( coxae) of the appendages. The fifth to seventh pereopods function as clasping appendages. They all have propodi with two spines on their inside margins. The seventh pair of pereopods are the longest of the three pairs, followed by the sixth pereopod pair and the fifth pereopod pair.

''C. mutica'' closely resemble '' Caprella acanthogaster'', also a native of East Asian waters. It may be difficult to distinguish the two species, particularly since ''Caprella mutica'' can exhibit considerable morphological variations among males. ''C. mutica'' can only be reliably differentiated by their setose first and second pereonites (smooth in ''C. acanthogaster''), as well as the elongated oval shape of their gills (linear in ''C. acanthogaster'').

Taxonomy and nomenclature

''Caprella mutica'' were first described in 1935 by A. Schurin from specimens collected from thePeter the Great Gulf

The Peter the Great Gulf (Russian: Залив Петра Великого) is a gulf on the southern coast of Primorsky Krai, Russia, and the largest gulf of the Sea of Japan. The gulf extends for from the Russian–North Korean border, at the ...

in the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it ...

. It belongs to the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

''Caprella

''Caprella'' is a large genus of skeleton shrimps belonging to the subfamily Caprellinae of the family Caprellidae. It includes approximately 170 species. The genus was first established by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in his great work ''Système ...

'' in the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

Caprellinae of the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Caprellidae, a group of highly specialized amphipods commonly known as skeleton shrimp. Caprellids are classified under the superfamily Caprelloidea of the infraorder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between Family_(biology), family and Class_(biology), class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classific ...

Caprellida.

''C. mutica'' are known as ''koshitoge-warekara'' ("spine-waist skeleton shrimp") in Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. In the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

and Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, where the first invasive populations of ''C. mutica'' in Europe were discovered, they are known as ''machospookkreeftje'' in Flemish

Flemish may refer to:

* Flemish, adjective for Flanders, Belgium

* Flemish region, one of the three regions of Belgium

*Flemish Community, one of the three constitutionally defined language communities of Belgium

* Flemish dialects, a Dutch dialec ...

(literally "macho

Machismo (; ; ; ) is the sense of being " manly" and self-reliant, a concept associated with "a strong sense of masculine pride: an exaggerated masculinity". Machismo is a term originating in the early 1940s and 1950s and its use more wi ...

ghost shrimp"). The name is derived from the junior synonym

In taxonomy, the scientific classification of living organisms, a synonym is an alternative scientific name for the accepted scientific name of a taxon. The botanical and zoological codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

...

( invalid name) ''Caprella macho'', applied in 1995 to the species by Dirk Platvoet ''et al.'' who initially believed they were a different species. "Macho" is a humorous reference to the characteristic "hairy chests" of the males of ''C. mutica''. ''Caprella acanthogaster humboldtiensis'', another invalid name of the species, was first applied to misidentified specimens of ''C. mutica'' recovered from Humboldt Bay

Humboldt Bay (Wiyot language, Wiyot: ''Wigi'') is a natural bay and a multi-basin, bar-built coastal lagoon located on the rugged North Coast (California), North Coast of California, entirely within Humboldt County, California, Humboldt County, ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

by Donald M. Martin in 1977. Some specimens collected from the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde, is the estuary of the River Clyde, on the west coast of Scotland. The Firth has some of the deepest coastal waters of the British Isles. The Firth is sheltered from the Atlantic Ocean by the Kintyre, Kintyre Peninsula. The ...

, Scotland in 1999 were also initially misidentified as '' Caprella tuberculata'', but have since been determined to be introduced ''C. mutica''.

Ecology and biology

''Caprella mutica'' inhabit shallow protected marine bodies of water. They can often be found in dense colonies attached to submerged artificial structures, marinemacroalgae

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of Macroscopic scale, macroscopic, Multicellular organism, multicellular, ocean, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), ''Brown algae, Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ...

, and other organisms. They are primarily omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize ...

detritivore

Detritivores (also known as detrivores, detritophages, detritus feeders or detritus eaters) are heterotrophs that obtain nutrients by consuming detritus (decomposing plant and animal parts as well as feces). There are many kinds of invertebrates, ...

s, but can adapt to other feeding methods depending on food availability. They are preyed upon by fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura (meaning "short tailed" in Greek language, Greek), which typically have a very short projecting tail-like abdomen#Arthropoda, abdomen, usually hidden entirely under the Thorax (arthropo ...

s, and several other predators.

''C. mutica'' are generally found in temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

and subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of hemiboreal regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Fennoscandia, Northwestern Russia, Siberia, and the Cair ...

regions. They can not tolerate water temperatures higher than . They also die within five minutes if exposed to water temperatures of . On the lower end, they can survive temperatures lower than , but are rendered immobile if not altogether in a state of suspended animation

Suspended animation is the slowing or stopping of biological function so that physiological capabilities are preserved. States of suspended animation are common in micro-organisms and some plant tissue, such as seeds. Many animals, including l ...

. Salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

tolerance of ''C. mutica'' does not go below 15 psu, and they are unable to survive in freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

habitats. However, in their native habitats, it has been observed that they can survive salinities as low as 11 psu. They are also sensitive to exposure to air, and will die within an hour if taken out of the water.

''C. mutica'' reproduce all throughout the year, with peak seasons in the summer months. Males are highly aggressive and exhibit sexual competition

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex (intrasexual selec ...

over the smaller females. The eggs, which average at 40 per female,Boos K (2009) Mechanisms of a successful immigration from north-east Asia: population dynamics, life history traits and interspecific interactions in the caprellid amphipod Caprella mutica Schurin 1935 (Crustacea, Amphipoda) in European coastal waters. Ph.D thesis, Freie Universität Berlin Breton G, Faasse M, are incubated for about 5 days at in the female's brood pouch. Upon hatching, they reach sexual maturity in about 21 to 46 days. Their average lifespan in laboratory conditions is 68.8 days for males and 82 days for females.

Habitat

In their native habitat, ''Caprella mutica'' are found in the infralittoral (orneritic

The neritic zone (or sublittoral zone) is the relatively shallow part of the ocean above the drop-off of the continental shelf, approximately in depth.

From the point of view of marine biology it forms a relatively stable and well-illuminated ...

) and littoral zone

The littoral zone, also called litoral or nearshore, is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely flood ...

s of sheltered bodies of water to a depth of about . They may spend their entire lives clinging to a substrate in an upright position. These substrates are typically floating with filamentous, leafy, branching, or turf

Sod is the upper layer of turf that is harvested for transplanting. Turf consists of a variable thickness of a soil medium that supports a community of turfgrasses.

In British and Australian English, sod is more commonly known as ''turf'', ...

-like structures of the same color as their body for camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

as well as transportation. ''C. mutica'' are poor swimmers and move around predominantly in an undulating inchworm-like fashion, using their posterior pereopods and gnathopods. They are generally reluctant to let go of their substrates and will only do so if agitated. Different populations in different substrates are known to exhibit different exoskeletal coloration, suggesting that they can change color to blend in with their environments. The exact mechanisms for this color change, however, remains unknown.

Substrates they are most commonly found on in their native habitats include beds and floating clumps of macroalgae

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of Macroscopic scale, macroscopic, Multicellular organism, multicellular, ocean, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), ''Brown algae, Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ...

like '' Sargassum muticum'', '' Sargassum miyabei'', '' Sargassum pallidum'', '' Neorhodomela larix'', '' Polysiphonia morrowii'', '' Cystoseira crassipes'', '' Laminaria japonica'', '' Chondrus'' spp., and ''Desmarestia viridis

Overview

''Desmarestia viridis'' is a species of brown algae and a member of the phylum Ochrophyta. It is also known as stringy acid kelp, and is the most acidic of the acid kelps with a vacuolar pH of about 1. It is best known for releasing su ...

''; as well as in marine plants (like eelgrass of the genus ''Zostera

''Zostera'' is a small genus of widely distributed seagrasses, commonly called marine eelgrass, or simply seagrass or eelgrass. The genus ''Zostera'' contains 15 species.

Ecology

'' Zostera marina'' is found on sandy substrates or in estuarie ...

''), hydrozoa

Hydrozoa (hydrozoans; from Ancient Greek ('; "water") and ('; "animals")) is a taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class (biology), class of individually very small, predatory animals, some solitary and some colonial, most of which inhabit saline wat ...

ns, and bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary Colony (biology), colonies. Typically about long, they have a spe ...

ns.

In their introduced ranges, they also tend to seek out organisms that exhibit structures their slender bodies can easily blend with. These include macroalgae like ''Ulva lactuca

''Ulva lactuca'', also known by the common name sea lettuce, is an edible green alga in the family Ulvaceae. It is the type species of the genus ''Ulva''. A synonym is ''U. fenestrata'', referring to its "windowed" or "holed" appearance. De ...

'', '' Ceramium'' spp., '' Plocamium'' spp., ''Cladophora

''Cladophora'' is a genus of reticulated filamentous green algae in the class Ulvophyceae. They may be referred to as reticulated algae, branching algae, or blanket weed. The genus has a worldwide distribution and is harvested for use as a food a ...

'' spp., '' Chorda filum'', ''Fucus vesiculosus

''Fucus vesiculosus'', known by the common names bladderwrack, black tang, rockweed, sea grapes, bladder fucus, sea oak, cut weed, dyers fucus, red fucus and rock wrack, is a seaweed found on the coasts of the North Sea, the western Baltic Sea ...

'', '' Pylaiella'' spp. and the introduced ''Sargassum muticum''; hydrozoans like ''Obelia

''Obelia'' is a genus of hydrozoans, a class of mainly marine and some freshwater animal species that have both polyp and medusa stages in their life cycle. Hydrozoa belongs to the phylum Cnidaria, which are aquatic (mainly marine) organisms ...

'' spp. and '' Tubularia indivisa''; bryozoans; tube-building amphipods like '' Monocorophium acherusicum'' and ''Jassa marmorata

''Jassa marmorata'' is a species of tube-building amphipod. It is native to the northeast Atlantic Ocean but has been introduced into northeast Asia. ''J. marmorata'' are greyish in colour with reddish brown markings. The can grow to a length of ...

''; and even soft-bodied tunicate

Tunicates are marine invertebrates belonging to the subphylum Tunicata ( ). This grouping is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ...

s like '' Ascidiella aspersa'' and ''Ciona intestinalis

''Ciona intestinalis'' (sometimes known by the common name of vase tunicate) is an ascidian (sea squirt), a tunicate with very soft tunic. Its Latin name literally means "pillar of intestines", referring to the fact that its body is a soft, tran ...

''.

In both their native and introduced ranges, ''C. mutica'' are also synanthropic

A synanthrope (from ancient Greek σύν ''sýn'' "together, with" and ἄνθρωπος ''ánthrōpos'' "man") is an organism that evolved to live near humans and benefit from human settlements and their environmental modifications (see also ...

, being found abundantly in fouling communities

Fouling communities are communities of organisms found on artificial surfaces like the sides of docks, marinas, harbors, and boats. Settlement panels made from a variety of substances have been used to monitor settlement patterns and to examine s ...

in artificial structures like submerged ropes, fishing nets, piling

A pile or piling is a vertical structural element of a deep foundation, driven or drilled deep into the ground at the building site. A deep foundation is a type of foundation that transfers building loads to the earth farther down from th ...

s, dock

The word dock () in American English refers to one or a group of human-made structures that are involved in the handling of boats or ships (usually on or near a shore). In British English, the term is not used the same way as in American Engl ...

s, buoy

A buoy (; ) is a buoyancy, floating device that can have many purposes. It can be anchored (stationary) or allowed to drift with ocean currents.

History

The ultimate origin of buoys is unknown, but by 1295 a seaman's manual referred to navig ...

s, aquaculture

Aquaculture (less commonly spelled aquiculture), also known as aquafarming, is the controlled cultivation ("farming") of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, algae and other organisms of value such as aquatic plants (e.g. Nelu ...

equipment, oil rig platforms, ship hull

A hull is the watertight body of a ship, boat, submarine, or flying boat. The hull may open at the top (such as a dinghy), or it may be fully or partially covered with a deck. Atop the deck may be a deckhouse and other superstructures, such as ...

s, and even offshore wind farm

A wind farm, also called a wind park or wind power plant, is a group of wind turbines in the same location used to produce electricity. Wind farms vary in size from a small number of turbines to several hundred wind turbines covering an exten ...

s. In their introduced ranges (particularly in Europe), they are primarily and even exclusively found inhabiting artificial structures.

''C. mutica'' can reach extremely high densities in their introduced range when colonizing artificial structures. A survey of ''C. mutica'' populations in Chaleur Bay

frame, Satellite image of Chaleur Bay (NASA). Chaleur Bay is the large bay in the centre of the image; the Gulf_of_St._Lawrence.html" ;"title="Gaspé Peninsula is to the north and the Gulf of St. Lawrence">Gaspé Peninsula is to the north and t ...

, Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

revealed concentrations of 468,800 individuals per ; while a survey in Dunstaffnage Bay, Firth of Lorn

The Firth of Lorn or Lorne () is the inlet of the sea between the south-east coast of the Isle of Mull and the mainland of Scotland. It includes a number of islands, and is noted for the variety of wildlife habitats that are found. In 2005, a l ...

, Scotland reported 319,000 individuals per . In contrast, ''C. mutica'' in their native habitats reach maximum densities of only around 1,220 to 2,600 individuals per . Populations reach peak numbers during the late summer (August to September) before experiencing a sharp decline in the winter months.

Diet and predators

''Caprella mutica'' areomnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize ...

highly adaptable opportunistic feeders. Examinations of their stomach contents reveal a highly varied diet that depended on the particular substrate they are found on. They are predominantly detritivore

Detritivores (also known as detrivores, detritophages, detritus feeders or detritus eaters) are heterotrophs that obtain nutrients by consuming detritus (decomposing plant and animal parts as well as feces). There are many kinds of invertebrates, ...

s, but have the remarkable ability of adjusting feeding methods from being grazers, scavenger

Scavengers are animals that consume Corpse decomposition, dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a he ...

s, filter feeder

Filter feeders are aquatic animals that acquire nutrients by feeding on organic matters, food particles or smaller organisms (bacteria, microalgae and zooplanktons) suspended in water, typically by having the water pass over or through a s ...

s, and even predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s depending on the conditions of their environments. ''C. mutica'' sieve food particles or small organisms from the water by waving their bodies back and forth, with the comb-like setae on their second pair of antennae extended. They then clean off trapped particles by bending their antennae down to their mouthparts. They also use their antennae to scrape food particles from surfaces of their bodies or the substrate that they are clinging to. The large gnathopods are used for striking at and grasping both mobile and sessile prey. Known prey organisms of ''C. mutica'' include algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

(both plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

ic and macroalgae), dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s, hydrozoans, bryozoans, diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s, copepod

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthos, benthic (living on the sedimen ...

s, brine shrimp

''Artemia'' is a genus of aquatic crustaceans also known as brine shrimp or ''Sea-Monkeys, sea monkeys''. It is the only genus in the Family (biology), family Artemiidae. The first historical record of the existence of ''Artemia'' dates back to t ...

s, and other amphipod

Amphipoda () is an order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphipod species cur ...

s. They are capable of feeding on suspended organic particles, including fish feed

Manufactured feeds are an important part of modern commercial aquaculture. They provide the balanced nutrition needed by farmed fish. The feeds, in the form of granules or pellets, give nutrition in a stable and concentrated form, enabling the ...

and decaying organic matter. ''C. mutica'' are also known to engage in cannibalistic behavior on dead and dying individuals of their own species or genus.

Like other caprellids, ''C. mutica'' are preyed upon predominantly by fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

and crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura (meaning "short tailed" in Greek language, Greek), which typically have a very short projecting tail-like abdomen#Arthropoda, abdomen, usually hidden entirely under the Thorax (arthropo ...

s. In their native habitats, the predators of ''Caprella mutica'' include the shore crab ''Carcinus maenas

''Carcinus maenas'' is a common littoral crab. It is known by different names around the world. In the British Isles, it is generally referred to as the shore crab or green shore crab. In North America and South Africa, it bears the name Europe ...

'' and the goldsinny wrasse ('' Ctenolabrus rupestris'') which consume them in large numbers. Other predators include nudibranch

Nudibranchs () are a group of soft-bodied marine gastropod molluscs, belonging to the order Nudibranchia, that shed their shells after their larval stage. They are noted for their often extraordinary colours and striking forms, and they have b ...

s, starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

, nemertean worm

Nemertea is a phylum of animals also known as ribbon worms or proboscis worms, consisting of about 1300 known species. Most ribbon worms are very slim, usually only a few millimeters wide, although a few have relatively short but wide bodies. ...

s, sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

s, and hydrozoans. They constitute a valuable food source for these organisms due to their high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acid

In biochemistry and nutrition, a polyunsaturated fat is a fat that contains a polyunsaturated fatty acid (abbreviated PUFA), which is a subclass of fatty acid characterized by a backbone with two or more carbon–carbon double bonds.

Some polyunsa ...

s and carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

s. They also provide an important link in the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

between plankton and larger fish. This, in addition to their relative abundance and fast growth rates, make them a potentially important resource for marine fish feed in aquaculture. Introduced populations of ''C. mutica'' have become a major part of the diets of native wild and farmed fish.

Reproduction and life history

Wild populations of ''Caprella mutica'' show a higher number of females than males. This may be related to the fact that females are aggressively defended by males from competing males, resulting in high male mortality. The larger sizes and greater visibility of males also make them more vulnerable targets for predators that rely on eyesight like fish. ''C. mutica'' are r-strategists. They reproduce all throughout the year, with peak seasons in the summer (March to July). Males exhibit

Males exhibit sexual competition

Sexual selection is a mechanism of evolution in which members of one sex choose mates of the other sex to mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of the opposite sex (intrasexual selec ...

and courting behavior. They aggressively engage in "boxing matches" using their large second pair of gnathopods in the presence of receptive females. These encounters often have lethal results, as the gnathopods and their poison teeth can be used to impale or slice an opponent in half. Males will also repeatedly touch the exoskeletons of the females with their antennae to detect signs of moulting (ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticle in many invertebrates of the clade Ecdysozoa. Since the cuticle of these animals typically forms a largely inelastic exoskeleton, it is shed during growth and a new, larger covering is formed. The remnant ...

). Like all crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, females are only capable of mating shortly after shedding their old hardened exoskeletons.

Amplexus

Amplexus (Latin "embrace") is a type of Mating, mating behavior exhibited by some External fertilization, externally fertilizing species (chiefly amphibians, Amphipoda, amphipods, and horseshoe crabs) in which a male grasps a female with his fro ...

lasts for 10 to 15 minutes. Once mated, the males will defend the females for a short period (around 15 minutes). After this period, the females begin to exhibit aggressive behavior and will drive off the males. They will then bend their fourth and fifth pereonites at a 90-degree angle. Once their genital openings (located on the fifth pereonite) are aligned with the opening of the brood pouches, they quickly deposit fertilized eggs into them. Females carrying fertilized eggs remain highly aggressive towards males throughout the brooding period, indicating maternal behavior intended to protect the developing embryo from male aggression.

A brood pouch of a female can contain 3 to 363 eggs, averaging at 74 eggs. Larger females tend to produce more eggs. The eggs are incubated inside the brood pouch for 30 to 40 days before hatching. Like all amphipods, caprellids lack a plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

ic larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

l stage and the hatchlings resemble miniature adults. The juveniles may cling to their mothers upon hatching and the females continue to protect their offspring that remain close. Hatchlings measure around and grow to an average of per instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'' 'form, likeness') is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, which occurs between each moult (''ecdysis'') until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to ...

.

''C. mutica'' mature rapidly, moulting at an average of once each week until they enter the "premature stage", becoming sexually differentiated at the fifth instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'' 'form, likeness') is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, which occurs between each moult (''ecdysis'') until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to ...

. The durations between moulting cycles then become longer in their seventh to ninth instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'' 'form, likeness') is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, which occurs between each moult (''ecdysis'') until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to ...

s, averaging at once every two weeks until sexual maturity. This can occur in as early as 21 days and not later than 46 days after hatching, depending on environmental conditions. In wild populations, however, this can take as much as six months when the juveniles are hatched in the late summer.

Males begin to increase in size at a faster rate with each successive moult after the seventh instar. Females, on the other hand, produce their first brood at the seventh instar. They may moult several times as adults, becoming sexually receptive each time until death. The average lifespan of ''C. mutica'' in laboratory conditions is 68.8 days for males and 82 days for females.

Distribution and invasive ecology

''Caprella mutica'' are native to the subarctic regions of the Sea of Japan in northwestern Asia. They were first discovered in the Peter the Great Gulf in the

''Caprella mutica'' are native to the subarctic regions of the Sea of Japan in northwestern Asia. They were first discovered in the Peter the Great Gulf in the federal subject

The federal subjects of Russia, also referred to as the subjects of the Russian Federation () or simply as the subjects of the federation (), are the administrative division, constituent entities of Russia, its top-level political division ...

of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Primorsky Krai

Primorsky Krai, informally known as Primorye, is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject (a krais of Russia, krai) of Russia, part of the Far Eastern Federal District in the Russian Far East. The types of inhabited localities in Russia, ...

. They were redescribed by the Japanese marine biologist Ishitaro Arimoto in 1976 who noted that they were also present in the island of Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

and surrounding regions. In a span of only 40 years, they have spread into other parts of the world through multiple accidental introductions (both primary and "stepping stone" secondary introductions) from the hulls or ballast water of international maritime traffic, aquaculture equipment, and shipments of the Pacific oyster ('' Crassostrea gigas'').

Genetic studies of the mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

(mtDNA) of the populations of ''C. mutica'' reveal high genetic diversity in the Sea of Japan region, unequivocally identifying it as their native range. In contrast, non-native populations in North America, Europe, and New Zealand had poor variation. The detection of genetic material present in non-native populations, however, also make it probable that there are unknown regions that ''C. mutica'' may also be native to; though it might also be simply that the sample groups used in the studies were too small. Comparisons of mtDNA of the different populations make it possible to trace the possible routes of introduction. The most likely of which is that the original non-native introduction was to the west coast of North America, which exhibit the highest genetic diversity in non-native populations. Multiple later introductions happened in Europe and eastern North America. From here, additional populations were transported to nearby ports. Europe and eastern North America are also the possible sources for the New Zealand ''C. mutica'' population.

North America

The first specimens of ''C. mutica'' outside of its native range was recovered fromHumboldt Bay

Humboldt Bay (Wiyot language, Wiyot: ''Wigi'') is a natural bay and a multi-basin, bar-built coastal lagoon located on the rugged North Coast (California), North Coast of California, entirely within Humboldt County, California, Humboldt County, ...

, California by Donald M. Martin in 1973. Martin misidentified them as a subspecies

In Taxonomy (biology), biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (Morphology (biology), morpholog ...

of ''C. acanthogaster''. He named them ''Caprella acanthogaster humboldtiensis''. Additional specimens (also treated as ''C. acanthogaster'' or ''C. acanthogaster humboldtiensis'') were recovered between 1976 and 1978 from the Oakland Estuary

The Oakland Estuary is the strait in the San Francisco Bay Area, California, separating the cities of Oakland, California, Oakland and Alameda, California, Alameda and the Alameda (island), Alameda Island from the East Bay mainland. On its weste ...

, Elkhorn Slough

Elkhorn Slough is a tidal slough and estuary on Monterey Bay in Monterey County, California. It is California's second largest estuary and the United States' first estuarine sanctuary. The community of Moss Landing and the Moss Landing Power Pl ...

, and San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

. It wasn't until 1981, when the specimens were correctly identified as ''C. mutica'' by Dan C. Marelli. Along with additional specimens discovered in 1983 in Coos Bay

Coos Bay (Hanis language, Coos language: Atsixiis or Hanisich) is an estuary where the Coos River enters the Pacific Ocean, the estuary is approximately 12 miles long and up to two miles wide. It is the largest estuary completely within Oregon sta ...

, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, these populations are believed to have been introduced to the area as a result of the importation of oyster spat of the Pacific oyster (''Crassostrea gigas'') from Japan for oyster farming

Oyster farming is an aquaculture (or mariculture) practice in which oysters are bred and raised mainly for their pearls, shells and inner organ tissue, which is eaten. Oyster farming was practiced by the ancient Rome, ancient Romans as early as the ...

. Oysters are usually transported with algae as a packing material, particularly '' Sargassum muticum'' in which ''C. mutica'' are associated with.

Populations of ''C. mutica'' discovered in Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

, Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

in the 1970s as well as additional populations noted in the states of Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

and California of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in the 2000s are believed to have been the result of shipping

Freight transport, also referred to as freight forwarding, is the physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo. The term shipping originally referred to transport by sea but in American English, it has been ...

activities and intracoastal secondary spreading of the original populations.

''C. mutica'' were also discovered in Ketchikan

Ketchikan ( ; ) is a city in and the borough seat of the Ketchikan Gateway Borough on Revillagigedo Island of Alaska. It is the state's southeasternmost major settlement. Downtown Ketchikan is a National Historic Landmark District.

With a po ...

, Sitka, Juneau

Juneau ( ; ), officially the City and Borough of Juneau, is the capital of the U.S. state of Alaska, located along the Gastineau Channel and the Alaskan panhandle. Juneau was named the capital of Alaska in 1906, when the government of wha ...

, Cordova, Kodiak, Kachemak Bay

Kachemak Bay ( Dena'ina: ''Tika Kaq’'') is a 40-mi-long (64 km) arm of Cook Inlet in the U.S. state of Alaska, located on the southwest side of the Kenai Peninsula. The communities of Homer, Halibut Cove, Seldovia, Nanwalek, Port Gra ...

, Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound ( Sugpiaq: ''Suungaaciq'') is a sound off the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the ...

, and Unalaska

The City of Unalaska (; ) is the main population center in the Aleutian Islands. The city is in the Aleutians West Census Area, a regional component of the Unorganized Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Unalaska is located on Unalaska Isl ...

in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

between 2000 and 2003. This was the first instance of a non-native marine species being found in the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; , "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before Alaska Purchase, 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain ...

. In 2009, they were discovered to have spread into British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

, Canada. This indicates that ''C. mutica'' have completely expanded up the entire west coast of North America.

In 2003, surveys by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

(MIT) Sea Grant along the Atlantic coast of the United States revealed multiple established populations in seaports along the coastlines of Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

to Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. In the same year, ''C. mutica'' were also reported in Passamaquoddy Bay

Passamaquoddy Bay () is an inlet of the Bay of Fundy, between the U.S. state of Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick, at the mouth of the St. Croix River. Most of the bay lies within Canada, with its western shore bounded by Was ...

and Chaleur Bay

frame, Satellite image of Chaleur Bay (NASA). Chaleur Bay is the large bay in the centre of the image; the Gulf_of_St._Lawrence.html" ;"title="Gaspé Peninsula is to the north and the Gulf of St. Lawrence">Gaspé Peninsula is to the north and t ...

of New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

and Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

, Canada.

Europe

''C. mutica'' populations in Europe were first found in theNetherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

in 1995. During a species inventory, several specimens of an unknown caprellid were recovered by Platvoet ''et al.'' from artificial structures in and around the Neeltje-Jans

Neeltje Jans () is an artificial island in the Netherlands in the province of Zeeland, halfway between Noord-Beveland and Schouwen-Duiveland in the Oosterschelde. It was constructed to facilitate the construction of the Oosterscheldedam.

After t ...

and the Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier in Burghsluis, Zeeland

Zeeland (; ), historically known in English by the Endonym and exonym, exonym Zealand, is the westernmost and least populous province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the southwest of the country, borders North Brabant to the east ...

. As with the case of the first discovery of ''C. mutica'' in North America, Platvoet ''et al.'' initially misidentified them as a new species. Remarking upon the resemblance of the caprellids to ''C. acanthogaster'', they named it ''Caprella macho''. They were later discovered to be introduced populations of ''C. mutica'' rather than a new species.

Since then, additional populations have been detected in Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

(1998), Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

(1999), Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

(2000), Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

(2000), England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

(2003), Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

(2003), Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

(2003), France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

(2004), and Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

(2005). They exist in extremely dense populations and are all associated with areas of high human activity. They are believed to have been introduced through shipping and aquaculture equipment from the United States and Asia. As of 2011, there have been no recorded sightings of ''C. mutica'' around the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, or the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

.

New Zealand

''Caprella mutica'' were first detected in New Zealand in the port ofTimaru

Timaru (; ) is a port city in the southern Canterbury Region of New Zealand, located southwest of Christchurch and about northeast of Dunedin on the eastern Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast of the South Island. The Timaru urban area is home to peo ...

, South Island

The South Island ( , 'the waters of Pounamu, Greenstone') is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand by surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by ...

in 2002. This was the first incident of ''C. mutica'' being reported in the southern hemisphere. Since then, more well-established populations of ''C. mutica'' have been found in Port Lyttelton in 2006, and in the Marlborough Sounds

The Marlborough Sounds (Māori language, te reo Māori: ''Te Tauihu-o-te-Waka'') are an extensive network of ria, sea-drowned valleys at the northern end of the South Island of New Zealand. The Marlborough Sounds were created by a combination ...

and Wellington Harbour

Wellington Harbour ( ), officially called Wellington Harbour / Port Nicholson, is a large natural harbour on the southern tip of New Zealand's North Island. The harbour entrance is from Cook Strait. Central Wellington is located on parts of ...

in 2007. Additional specimens were also recovered from the hulls of vessels in other ports, though they did not seem to have established colonies in the ports themselves. Genetic studies of the New Zealand populations suggests a possibility that these were secondarily introduced from non-native populations of ''C. mutica'' in the Atlantic through ballast water in the sea chests of international shipping.

Impact

The direct environmental and economic impacts of introduced ''C. mutica'' populations remain unknown. They provide valuable food sources for larger predators, particularly fish. In New Zealand, for example, they have become part of the diet of the native big-belly seahorse ('' Hippocampus abdominalis''). In Europe, wild and farmed fish like the common dab ('' Limanda limanda''), European perch (''Perca fluviatilis

The European perch (''Perca fluviatilis''), also known as the common perch, redfin perch, big-scaled redfin, English perch, Euro perch, Eurasian perch, Eurasian river perch, Hatch, poor man's rockfish or in Anglophone parts of Europe, simply the ...

''), and the Atlantic salmon (''Salmo salar

The Atlantic salmon (''Salmo salar'') is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. It is the third largest of the Salmonidae, behind Hucho taimen, Siberian taimen and Pacific Chinook salmon, growing up to a meter in length. Atlan ...

''), consume large amounts of non-native ''C. mutica''.

However, their larger sizes and very aggressive behavior also make them a serious threat to native species of skeleton shrimp. A study in 2009 on the native populations of ''Caprella linearis

''Caprella linearis'' (linear skeleton shrimp) is a species of skeleton shrimp in the genus '' Caprella''. It is native to the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and the Arctic Ocean. It closely resembles '' Caprella septentrionalis'' with which it ...

'', a smaller caprellid species in the Helgoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

region of the German Bight

The German Bight ( ; ; ); ; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and Germany to the east (the Jutland peninsula). To the north and west i ...

in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, have revealed that ''C. linearis'' have more or less vanished and have been replaced by ''C. mutica''. ''C. mutica'' fouling

Fouling is the accumulation of unwanted material on solid surfaces. The fouling materials can consist of either living organisms (biofouling, organic) or a non-living substance (inorganic). Fouling is usually distinguished from other surfac ...

populations may also incur minor economic effects through the cost of their removal from submerged aquaculture equipment and ship hulls.

Control

There are no known effective control measures for invasive ''Caprella mutica'' populations as of 2012. It has been suggested that the seasonal population fluctuations may be taken advantage of. Eradication efforts done during the winter months when ''C. mutica'' populations are dormant and at their lowest numbers, are potentially more effective in preventing their recovery during the summer months. Because of the great difficulty in detecting and removing them, however, control methods will likely focus on preserving native species populations rather than the eradication of established ''C. mutica''.See also

*List of invasive species

These are lists of invasive species by country or region. A species is regarded as invasive if it has been introduced by human action to a location, area, or region where it did not previously occur naturally (i.e., is not a native species), becom ...

*List of the world's 100 worst invasive species

100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species is a list of invasive species compiled in 2000 from the Global Invasive Species Database, a database of invasive species around the world. ISSG booklet giving the original 100 species. The database i ...

References

External links

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2140429 Corophiida Crustaceans described in 1935