Calvinism In France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a religious group of

A term used originally in derision, ''Huguenot'' has unclear origins. Various hypotheses have been promoted. The term may have been a combined reference to the Swiss politician

A term used originally in derision, ''Huguenot'' has unclear origins. Various hypotheses have been promoted. The term may have been a combined reference to the Swiss politician

The Huguenot cross is the distinctive emblem of the Huguenots (). It is now an official symbol of the (French Protestant church). Huguenot descendants sometimes display this symbol as a sign of (recognition) between them.

The Huguenot cross is the distinctive emblem of the Huguenots (). It is now an official symbol of the (French Protestant church). Huguenot descendants sometimes display this symbol as a sign of (recognition) between them.

The issue of demographic strength and geographical spread of the

The issue of demographic strength and geographical spread of the

The availability of the Bible in

The availability of the Bible in

p. 389 They were suppressed by Francis I in 1545 in the

These tensions spurred eight civil wars, interrupted by periods of relative calm, between 1562 and 1598. With each break in peace, the Huguenots' trust in the Catholic throne diminished, and the violence became more severe, and Protestant demands became grander, until a lasting cessation of open hostility finally occurred in 1598. The wars gradually took on a dynastic character, developing into an extended feud between the Houses of

These tensions spurred eight civil wars, interrupted by periods of relative calm, between 1562 and 1598. With each break in peace, the Huguenots' trust in the Catholic throne diminished, and the violence became more severe, and Protestant demands became grander, until a lasting cessation of open hostility finally occurred in 1598. The wars gradually took on a dynastic character, developing into an extended feud between the Houses of

, ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', 1911 (some sources say hundreds) of Huguenots were killed, and about 200 were wounded. It was in this year that some Huguenots destroyed the tomb and remains of Saint

The pattern of warfare, followed by brief periods of peace, continued for nearly another quarter-century. The warfare was definitively quelled in 1598, when Henry of Navarre, having succeeded to the French throne as Henry IV, and having recanted Protestantism in favour of Roman Catholicism in order to obtain the French crown, issued the

The pattern of warfare, followed by brief periods of peace, continued for nearly another quarter-century. The warfare was definitively quelled in 1598, when Henry of Navarre, having succeeded to the French throne as Henry IV, and having recanted Protestantism in favour of Roman Catholicism in order to obtain the French crown, issued the  By 1620, the Huguenots were on the defensive, and the government increasingly applied pressure. A series of three small civil wars known as the

By 1620, the Huguenots were on the defensive, and the government increasingly applied pressure. A series of three small civil wars known as the

The revocation forbade Protestant services, required education of children as Catholics, and prohibited emigration. It proved disastrous to the Huguenots and costly for France. It precipitated civil bloodshed, ruined commerce, and resulted in the illegal flight from the country of hundreds of thousands of Protestants, many of whom were intellectuals, doctors and business leaders whose skills were transferred to Britain as well as Holland, Switzerland, Prussia, South Africa and other places they fled to. 4,000 emigrated to the

The revocation forbade Protestant services, required education of children as Catholics, and prohibited emigration. It proved disastrous to the Huguenots and costly for France. It precipitated civil bloodshed, ruined commerce, and resulted in the illegal flight from the country of hundreds of thousands of Protestants, many of whom were intellectuals, doctors and business leaders whose skills were transferred to Britain as well as Holland, Switzerland, Prussia, South Africa and other places they fled to. 4,000 emigrated to the

By the 1760s Protestantism was no longer a favourite religion of the elite. By then, most Protestants were Cévennes peasants. It was still illegal, and, although the law was seldom enforced, it could be a threat or a nuisance to Protestants. Calvinists lived primarily in the

By the 1760s Protestantism was no longer a favourite religion of the elite. By then, most Protestants were Cévennes peasants. It was still illegal, and, although the law was seldom enforced, it could be a threat or a nuisance to Protestants. Calvinists lived primarily in the

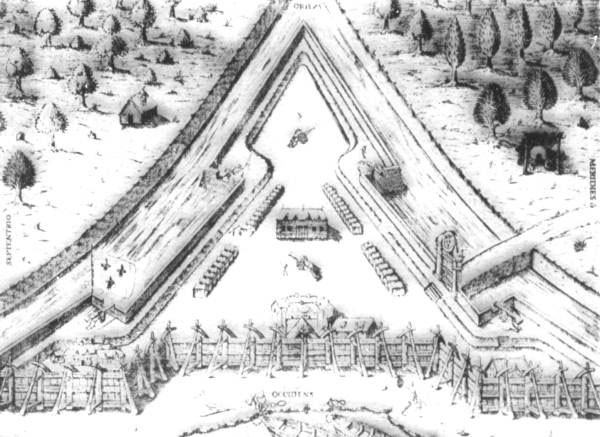

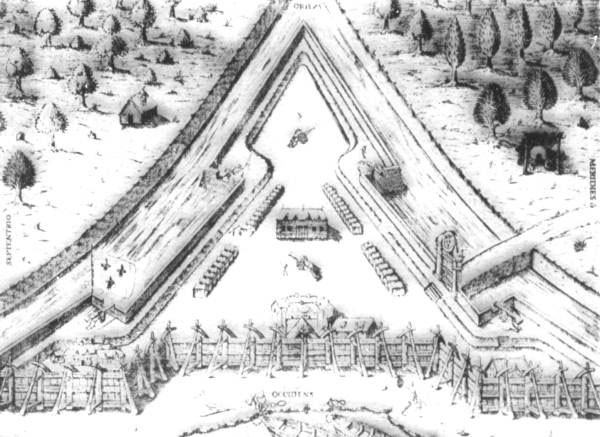

French Huguenots made two attempts to establish a haven in North America. In 1562, naval officer Jean Ribault led an expedition that explored Florida and the present-day Southeastern United States, Southeastern US, and founded the outpost of Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site, Charlesfort on Parris Island, South Carolina. The French Wars of Religion precluded a return voyage, and the outpost was abandoned. In 1564, Ribault's former lieutenant René Goulaine de Laudonnière launched a second voyage to build a colony; he established Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. War at home again precluded a resupply mission, and the colony struggled. In 1565 the Spanish decided to enforce their claim to , and sent Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who established the settlement of St. Augustine, Florida, St. Augustine near Fort Caroline. Menéndez' forces routed the French and executed most of the Protestant captives.

French Huguenots made two attempts to establish a haven in North America. In 1562, naval officer Jean Ribault led an expedition that explored Florida and the present-day Southeastern United States, Southeastern US, and founded the outpost of Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site, Charlesfort on Parris Island, South Carolina. The French Wars of Religion precluded a return voyage, and the outpost was abandoned. In 1564, Ribault's former lieutenant René Goulaine de Laudonnière launched a second voyage to build a colony; he established Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. War at home again precluded a resupply mission, and the colony struggled. In 1565 the Spanish decided to enforce their claim to , and sent Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who established the settlement of St. Augustine, Florida, St. Augustine near Fort Caroline. Menéndez' forces routed the French and executed most of the Protestant captives.

Barred by the government from settling in New France, Huguenots led by Jessé de Forest, sailed to North America in 1624 and settled instead in the Dutch colony of New Netherland (later incorporated into New York and New Jersey); as well as Great Britain's colonies, including Nova Scotia. A number of New Amsterdam's families were of Huguenot origin, often having emigrated as refugees to the Netherlands in the previous century. In 1628 the Huguenots established a congregation as (the French church in New Amsterdam). This parish continues today as , now a part of the Episcopal Church (United States), Episcopal Church (Anglican) communion, and welcomes Francophone New Yorkers from all over the world. Upon their arrival in New Amsterdam, Huguenots were offered land directly across from Manhattan on Long Island for a permanent settlement and chose the harbour at the end of Newtown Creek, becoming the first Europeans to live in Brooklyn, then known as Boschwick, in the neighbourhood now known as Bushwick, Brooklyn, Bushwick.

Barred by the government from settling in New France, Huguenots led by Jessé de Forest, sailed to North America in 1624 and settled instead in the Dutch colony of New Netherland (later incorporated into New York and New Jersey); as well as Great Britain's colonies, including Nova Scotia. A number of New Amsterdam's families were of Huguenot origin, often having emigrated as refugees to the Netherlands in the previous century. In 1628 the Huguenots established a congregation as (the French church in New Amsterdam). This parish continues today as , now a part of the Episcopal Church (United States), Episcopal Church (Anglican) communion, and welcomes Francophone New Yorkers from all over the world. Upon their arrival in New Amsterdam, Huguenots were offered land directly across from Manhattan on Long Island for a permanent settlement and chose the harbour at the end of Newtown Creek, becoming the first Europeans to live in Brooklyn, then known as Boschwick, in the neighbourhood now known as Bushwick, Brooklyn, Bushwick.

Huguenot immigrants settled throughout pre-colonial America, including in New Amsterdam (New York City), some 21 miles north of New York in a town which they named New Rochelle, New York, New Rochelle, and some further upstate in New Paltz (village), New York, New Paltz. The "Huguenot Street Historic District" in New Paltz has been designated a National Historic Landmark site and contains one of the oldest streets in the United States of America. A small group of Huguenots also settled on the Rossville, Staten Island, south shore of Staten Island along the New York Harbor, for which the current neighbourhood of Huguenot, Staten Island, Huguenot was named. Huguenot refugees also settled in the Delaware Valley, Delaware River Valley of Eastern Pennsylvania and Hunterdon County, New Jersey in 1725. Frenchtown, New Jersey, Frenchtown in New Jersey bears the mark of early settlers.

New Rochelle, New York, New Rochelle, located in the county of Westchester, New York, Westchester on the north shore of Long Island Sound, seemed to be the great location of the Huguenots in New York. It is said that they landed on the coastline peninsula of Davenports Neck called "Bauffet's Point" after travelling from England where they had previously taken refuge on account of religious persecution, four years before the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. They purchased from John Pell, Lord of Pelham Manor, New York, Pelham Manor, a tract of land consisting of six thousand one hundred acres with the help of Jacob Leisler. It was named New Rochelle after La Rochelle, their former strong-hold in France. A small wooden church was first erected in the community, followed by a second church that was built of stone. Previous to the erection of it, the strong men would often walk twenty-three miles on Saturday evening, the distance by the road from New Rochelle to New York, to attend the Sunday service. The church was eventually replaced by a third, Trinity-St. Paul's Episcopal Church, which contains heirlooms including the original bell from the French Huguenot Church on Pine Street in New York City, which is preserved as a relic in the tower room. The Huguenot cemetery, or the "Huguenot Burial Ground", has since been recognised as a historic cemetery that is the final resting place for a wide range of the Huguenot founders, early settlers and prominent citizens dating back more than three centuries.

Some Huguenot immigrants settled in central and eastern Pennsylvania. They assimilated with the predominantly Pennsylvania Dutch, Pennsylvania German settlers of the area.

In 1700 several hundred French Huguenots migrated from England to the colony of Virginia, where the King William III of England had promised them land grants in Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, Lower Norfolk County. When they arrived, colonial authorities offered them instead land 20 miles above the falls of the James River, at the abandoned Monacan Indian Nation, Monacan village known as Manakin Town, now in Goochland County. Some settlers landed in present-day Chesterfield County, Virginia, Chesterfield County. On 12 May 1705, the Virginia General Assembly passed an act to naturalise the 148 Huguenots still resident at Manakintown. Of the original 390 settlers in the isolated settlement, many had died; others lived outside town on farms in the English style; and others moved to different areas. Gradually they intermarried with their English neighbours. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, descendants of the French migrated west into the Piedmont, and across the Appalachian Mountains into the West of what became Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and other states. In the Manakintown area, the Huguenot Memorial Bridge across the James River and Huguenot Road were named in their honour, as were many local features, including several schools, including Huguenot High School.

Huguenot immigrants settled throughout pre-colonial America, including in New Amsterdam (New York City), some 21 miles north of New York in a town which they named New Rochelle, New York, New Rochelle, and some further upstate in New Paltz (village), New York, New Paltz. The "Huguenot Street Historic District" in New Paltz has been designated a National Historic Landmark site and contains one of the oldest streets in the United States of America. A small group of Huguenots also settled on the Rossville, Staten Island, south shore of Staten Island along the New York Harbor, for which the current neighbourhood of Huguenot, Staten Island, Huguenot was named. Huguenot refugees also settled in the Delaware Valley, Delaware River Valley of Eastern Pennsylvania and Hunterdon County, New Jersey in 1725. Frenchtown, New Jersey, Frenchtown in New Jersey bears the mark of early settlers.

New Rochelle, New York, New Rochelle, located in the county of Westchester, New York, Westchester on the north shore of Long Island Sound, seemed to be the great location of the Huguenots in New York. It is said that they landed on the coastline peninsula of Davenports Neck called "Bauffet's Point" after travelling from England where they had previously taken refuge on account of religious persecution, four years before the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. They purchased from John Pell, Lord of Pelham Manor, New York, Pelham Manor, a tract of land consisting of six thousand one hundred acres with the help of Jacob Leisler. It was named New Rochelle after La Rochelle, their former strong-hold in France. A small wooden church was first erected in the community, followed by a second church that was built of stone. Previous to the erection of it, the strong men would often walk twenty-three miles on Saturday evening, the distance by the road from New Rochelle to New York, to attend the Sunday service. The church was eventually replaced by a third, Trinity-St. Paul's Episcopal Church, which contains heirlooms including the original bell from the French Huguenot Church on Pine Street in New York City, which is preserved as a relic in the tower room. The Huguenot cemetery, or the "Huguenot Burial Ground", has since been recognised as a historic cemetery that is the final resting place for a wide range of the Huguenot founders, early settlers and prominent citizens dating back more than three centuries.

Some Huguenot immigrants settled in central and eastern Pennsylvania. They assimilated with the predominantly Pennsylvania Dutch, Pennsylvania German settlers of the area.

In 1700 several hundred French Huguenots migrated from England to the colony of Virginia, where the King William III of England had promised them land grants in Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, Lower Norfolk County. When they arrived, colonial authorities offered them instead land 20 miles above the falls of the James River, at the abandoned Monacan Indian Nation, Monacan village known as Manakin Town, now in Goochland County. Some settlers landed in present-day Chesterfield County, Virginia, Chesterfield County. On 12 May 1705, the Virginia General Assembly passed an act to naturalise the 148 Huguenots still resident at Manakintown. Of the original 390 settlers in the isolated settlement, many had died; others lived outside town on farms in the English style; and others moved to different areas. Gradually they intermarried with their English neighbours. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, descendants of the French migrated west into the Piedmont, and across the Appalachian Mountains into the West of what became Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and other states. In the Manakintown area, the Huguenot Memorial Bridge across the James River and Huguenot Road were named in their honour, as were many local features, including several schools, including Huguenot High School.

In the early years, many Huguenots also settled in the area of present-day Charleston, South Carolina. In 1685, Rev. Elie Prioleau from the town of Pons, Charente-Maritime, Pons in France, was among the first to settle there. He became pastor of the first Huguenot church in North America in that city. After the Revocation of the

In the early years, many Huguenots also settled in the area of present-day Charleston, South Carolina. In 1685, Rev. Elie Prioleau from the town of Pons, Charente-Maritime, Pons in France, was among the first to settle there. He became pastor of the first Huguenot church in North America in that city. After the Revocation of the

Other evidence of the Walloons and Huguenots in Canterbury includes a block of houses in Turnagain Lane, where weavers' windows survive on the top floor, as many Huguenots worked as weavers. The Weavers, a timber framing, half-timbered house by the river, was the site of a weaving school from the late 16th century to about 1830. (It has been adapted as a restaurant—see illustration above. The house derives its name from a weaving school which was moved there in the last years of the 19th century, reviving an earlier use.) Other refugees practiced the variety of occupations necessary to sustain the community as distinct from the indigenous population. Such economic separation was the condition of the refugees' initial acceptance in the city. They also settled elsewhere in Kent, particularly Sandwich, Kent, Sandwich, Faversham, Kent, Faversham and Maidstone—towns in which there used to be refugee churches.

The French Protestant Church of London was established by Royal Charter in 1550. It is now located at Soho Square. Huguenot refugees flocked to Shoreditch, London. They established a major weaving industry in and around Spitalfields (see Petticoat Lane and the Tenterground) in East London. In Wandsworth, their gardening skills benefited the Battersea market gardens. The flight of Huguenot refugees from

Other evidence of the Walloons and Huguenots in Canterbury includes a block of houses in Turnagain Lane, where weavers' windows survive on the top floor, as many Huguenots worked as weavers. The Weavers, a timber framing, half-timbered house by the river, was the site of a weaving school from the late 16th century to about 1830. (It has been adapted as a restaurant—see illustration above. The house derives its name from a weaving school which was moved there in the last years of the 19th century, reviving an earlier use.) Other refugees practiced the variety of occupations necessary to sustain the community as distinct from the indigenous population. Such economic separation was the condition of the refugees' initial acceptance in the city. They also settled elsewhere in Kent, particularly Sandwich, Kent, Sandwich, Faversham, Kent, Faversham and Maidstone—towns in which there used to be refugee churches.

The French Protestant Church of London was established by Royal Charter in 1550. It is now located at Soho Square. Huguenot refugees flocked to Shoreditch, London. They established a major weaving industry in and around Spitalfields (see Petticoat Lane and the Tenterground) in East London. In Wandsworth, their gardening skills benefited the Battersea market gardens. The flight of Huguenot refugees from

After the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572, some persecuted Huguenots fled to Poland, taking advantage of its religious tolerance confirmed by the Warsaw Confederation, marking the first significant historical wave of French people in Poland, French migration to Poland.

Around 1685, Huguenot refugees found a safe haven in the Lutheran and Reformed states in Germany and Scandinavia. Nearly 50,000 Huguenots established themselves in Germany, 20,000 of whom were welcomed in Brandenburg-Prussia, where

After the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572, some persecuted Huguenots fled to Poland, taking advantage of its religious tolerance confirmed by the Warsaw Confederation, marking the first significant historical wave of French people in Poland, French migration to Poland.

Around 1685, Huguenot refugees found a safe haven in the Lutheran and Reformed states in Germany and Scandinavia. Nearly 50,000 Huguenots established themselves in Germany, 20,000 of whom were welcomed in Brandenburg-Prussia, where  In Berlin the Huguenots created two new neighborhoods: Dorotheenstadt and Friedrichstadt (Berlin), Friedrichstadt. By 1700 one fifth of the city's population was French-speaking. The Berlin Huguenots preserved the French language in their church services for nearly a century. They ultimately decided to switch to German in protest against the occupation of Prussia by Napoleon in 1806–07. Many of their descendants rose to positions of prominence. Several congregations were founded throughout Germany and Scandinavia, such as those of Fredericia (Denmark), Berlin, Stockholm, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Helsinki, and Emden.

Prince Louis de Condé, along with his sons Daniel and Osias, arranged with Count Ludwig von Nassau-Saarbrücken to establish a Huguenot community in present-day Saarland in 1604. The Count supported mercantilism and welcomed technically skilled immigrants into his lands, regardless of their religion. The Condés established a thriving glass-making works, which provided wealth to the principality for many years. Other founding families created enterprises based on textiles and such traditional Huguenot occupations in France. The community and its congregation remain active to this day, with descendants of many of the founding families still living in the region. Some members of this community emigrated to the United States in the 1890s.

In Bad Karlshafen, Hessen, Germany is the Huguenot Museum and Huguenot archive. The collection includes family histories, a library, and a picture archive.

In Berlin the Huguenots created two new neighborhoods: Dorotheenstadt and Friedrichstadt (Berlin), Friedrichstadt. By 1700 one fifth of the city's population was French-speaking. The Berlin Huguenots preserved the French language in their church services for nearly a century. They ultimately decided to switch to German in protest against the occupation of Prussia by Napoleon in 1806–07. Many of their descendants rose to positions of prominence. Several congregations were founded throughout Germany and Scandinavia, such as those of Fredericia (Denmark), Berlin, Stockholm, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Helsinki, and Emden.

Prince Louis de Condé, along with his sons Daniel and Osias, arranged with Count Ludwig von Nassau-Saarbrücken to establish a Huguenot community in present-day Saarland in 1604. The Count supported mercantilism and welcomed technically skilled immigrants into his lands, regardless of their religion. The Condés established a thriving glass-making works, which provided wealth to the principality for many years. Other founding families created enterprises based on textiles and such traditional Huguenot occupations in France. The community and its congregation remain active to this day, with descendants of many of the founding families still living in the region. Some members of this community emigrated to the United States in the 1890s.

In Bad Karlshafen, Hessen, Germany is the Huguenot Museum and Huguenot archive. The collection includes family histories, a library, and a picture archive.

excerpt and text search

* Gerson, Noel B. ''The Edict of Nantes'' (Grosset & Dunlap, 1969), for secondary schools. * Gilman, C. Malcolm. ''The Huguenot Migration in Europe and America, its Cause and Effect'' (1962) * Matthew Glozier, Glozier, Matthew and David Onnekink, eds. ''War, Religion and Service. Huguenot Soldiering, 1685–1713'' (2007) * Matthew Glozier, Glozier, Matthew ''The Huguenot soldiers of William of Orange and the Glorious Revolution of 1688: the lions of Judah'' (Brighton, 2002) * Gwynn, Robin D. ''Huguenot Heritage: The History and Contribution of the Huguenots in England'' (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985). * Kamil, Neil. ''Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots' New World, 1517–1751'' Johns Hopkins U. Press, 2005. 1058 pp. * Lachenicht, Susanne. "Huguenot Immigrants and the Formation of National Identities, 1548–1787", ''Historical Journal'' 2007 50(2): 309–331, * Lotz-Heumann, Ute

''Confessional Migration of the Reformed: The Huguenots''

European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2012, retrieved: 11 July 2012. * McClain, Molly. "A Letter from Carolina, 1688: French Huguenots in the New World." William and Mary Quarterly. 3rd. ser., 64 (April 2007): 377–394. * Mentzer, Raymond A. and Andrew Spicer. ''Society and Culture in the Huguenot World, 1559–1685'' (2007

excerpt and text search

* Murdoch, Tessa, and Randolph Vigne. The ''French Hospital (La Providence), French Hospital in England: Its Huguenot History and Collections'' Cambridge: John Adamson (publisher), John Adamson, 2009 * Parsons, Jotham, ed. ''The Edict of Nantes: Five Essays and a New Translation'' (National Huguenot Society, 1998). * Ruymbeke, Bertrand Van. ''New Babylon to Eden: The Huguenots and Their Migration to Colonial South Carolina.'' U. of South Carolina Press, 2006. 396 pp * Scoville, Warren Candler. ''The persecution of Huguenots and French economic development, 1680–1720'' (U of California Press, 1960). * Scoville, Warren C. "The Huguenots and the diffusion of technology. I." ''Journal of political economy'' 60.4 (1952): 294–311

part I online

Part2: Vol. 60, No. 5 (Oct. 1952), pp. 392–41

online part 2

* Soman, Alfred. ''The Massacre of St. Bartholomew: Reappraisals and Documents'' (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1974) * Treasure, G. R. R. ''Seventeenth Century France'' (2nd ed., 1981) pp. 371–396. * VanRuymbeke, Bertrand and Sparks, Randy J., eds. ''Memory and Identity: The Huguenots in France and the Atlantic Diaspora'', U. of South Carolina Press, 2003. 352 pp. * Wijsenbeek, Thera. "Identity Lost: Huguenot Refugees in the Dutch Republic and its Former Colonies in North America and South Africa, 1650 To 1750: A Comparison", ''South African Historical Journal'' 2007 (59): 79–102 * Wolfe, Michael. ''The Conversion of Henri IV: Politics, Power, and Religious Belief in Early Modern France'' (1993).

The Huguenot Library

at University College London contains approximate 6500 books and pamphlets including 1500 rare books

Historic Huguenot Street

Huguenot Fellowship

The Huguenot Society of Australia

Library for Huguenot History, Germany

The National Huguenot Society

The Huguenot Society of America

Huguenot Society of Great Britain & Ireland

Huguenots of Spitalfields

''Huguenots and Jews of the Languedoc''

About the inhabitants of Southern France and how they came to be called French Protestants

''Early Prayer Books of America: Being a Descriptive Account of Prayer Books Published in the United States, Mexico and Canada''

by Rev. John Wright, D.D. St Paul, MN: Privately Printed, 1898. Pages 188 to 210 are entitled "The Prayer Book of the French Protestants, Charleston, South Carolina." (597 pdfs)

''The French Protestant (Huguenot) Church in the city of Charleston, South Carolina''

Includes history, text of memorial tablets, and the rules adopted in 1869. (1898, 40 pdfs)

''La Liturgie: ou La Manière de célébrer le service Divin; Qui est établie Dans le Eglises de la Principauté de Neufchatel & Vallangin''

(1713, 160 pdfs)

''La Liturgie: ou La Manière de célébrer le service Divin; Qui est établie Dans le Eglises de la Principauté de Neufchatel & Vallangin''

Revised and corrected second edition. (1737, 302 pdfs)

''La Liturgie: ou La Manière de Célébrer le Service Divin, Comme elle est établie Dans le Eglises de la Principauté de Neufchatel & Vallangin. Nouvelle édition, Augmentée de quelques Prieres, Collectes & Cantiques''

(1772, 256 pdfs)

''La Liturgie: ou La Manière de Célébrer le Service Divin, qui est établie Dans le Eglises de la Principauté de Neufchatel & Vallangin. Cinquieme édition, revue, corrigée & augmentée''

(1799, 232 pdfs)

''La Liturgie, ou La Manière de Célébrer le Service Divin, dans le églises du Canton de Vaud''

(1807, 120 pdfs)

''The Liturgy of the French Protestant Church, Translated from the Editions of 1737 and 1772, Published at Neufchatel, with Additional Prayers, Carefully Selected, and Some Alterations: Arranged for the Use of the Congregation in the City of Charleston, S. C.''

Charleston, SC: James S. Burgess, 1835. (205 pdfs)

''The Liturgy of the French Protestant Church, Translated from the Editions of 1737 and 1772, Published at Neufchatel, with Additional Prayers Carefully Selected, and Some Alterations. Arranged for the Use of the Congregation in the City of Charleston, S. C.''

New York: Charles M. Cornwell, Steam Printer, 1869. (186 pdfs) * ''The Liturgy, or Forms of Divine Service, of the French Protestant Church, of Charleston, S. C., Translated from the Liturgy of the Churches of Neufchatel and Vallangin: editions of 1737 and 1772. With Some Additional Prayers, Carefully Selected. The Whole Adapted to Public Worship in the United States of America.'' Third edition. New York: Anson D. F. Randolph & Company, 1853. 228 pp

Google Books

and th

Internet Archive

Available also fro

Making of America Books

as a DLXS file or in hardcover.

''The Liturgy Used in the Churches of the Principality of Neufchatel: with a Letter from the Learned Dr. Jablonski, Concerning the Nature of Liturgies: To which is Added, The Form of Prayer lately introduced into the Church of Geneva''

(1712, 143 pdfs)

Manifesto, (or Declaration of Principles), of the French Protestant Church of London, Founded by Charter of Edward VI. 24 July, A.D. 1550.

By Order of the Consistory. London, England: Messrs. Seeleys, 1850.

''Preamble and rules for the government of the French Protestant Church of Charleston: adopted at meetings of the corporation held on the 12th and the 19th of November, 1843''

(1845, 26 pdfs)

''Synodicon in Gallia Reformata: or, the Acts, Decisions, Decrees, and Canons of those Famous National Councils of the Reformed Churches in France''

by John Quick (divine), John Quick. Volume 1 of 2. (1692, 693 pdfs)

Synodicon in Gallia Reformata: or, the Acts, Decisions, Decrees, and Canons of those Famous National Councils of the Reformed Churches in France

by John Quick. Volume 2 of 2. (1692, 615 pdfs) * {{Authority control Huguenots, Anti-Catholicism in France Christian ethnoreligious groups French Protestants French Wars of Religion Religion in the Ancien Régime

French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

who held to the Reformed (Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster

Burgomaster (alternatively spelled burgermeister, ) is the English form of various terms in or derived from Germanic languages for the chief magistrate or executive of a city or town. The name in English was derived from the Dutch .

In so ...

Besançon Hugues

Besançon Hugues (; 1487 – 1532) was a Swiss political and religious leader who was a member of the Grand Council of Geneva. He participated in the rebellion against the rule of the Savoy dynasty, which led to the independence of Geneva in 15 ...

, was in common use by the mid-16th century. ''Huguenot'' was frequently used in reference to those of the Reformed Church of France

The Reformed Church of France (, ERF) was the main Protestant denomination in France with a Calvinist orientation that could be traced back directly to John Calvin. In 2013, the Church merged with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in France to ...

from the time of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

. By contrast, the Protestant populations of eastern France, in Alsace

Alsace (, ; ) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in the Grand Est administrative region of northeastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine, next to Germany and Switzerland. In January 2021, it had a population of 1,9 ...

, Moselle

The Moselle ( , ; ; ) is a river that rises in the Vosges mountains and flows through north-eastern France and Luxembourg to western Germany. It is a bank (geography), left bank tributary of the Rhine, which it joins at Koblenz. A sm ...

, and Montbéliard

Montbéliard (; traditional ) is a town in the Doubs department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in eastern France, about from the border with Switzerland. It is one of the two subprefectures of the department.

History

Montbéliard is ...

, were mainly Lutherans

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched the Reformation in 15 ...

.

In his ''Encyclopedia of Protestantism'', Hans Hillerbrand wrote that on the eve of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre () in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French Wars of Religion. Traditionally believed ...

in 1572, the Huguenot community made up as much as 10% of the French population. By 1600, it had declined to 7–8%, and was reduced further late in the century after the return of persecution under Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, who instituted the ''dragonnades

The ''Dragonnades'' was a policy implemented by Louis XIV in 1681 to force French Protestants known as Huguenots to convert to Catholicism. It involved the billeting of dragoons of the French Royal Army in Huguenot households, with the so ...

'' to forcibly convert Protestants, and then finally revoked all Protestant rights in his Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (18 October 1685, published 22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to prac ...

of 1685. In 1686, the Protestant population sat at 1% of the population.

The Huguenots were concentrated in the southern and western parts of the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

. As Huguenots gained influence and more openly displayed their faith, Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

hostility grew. A series of religious conflicts followed, known as the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

, fought intermittently from 1562 to 1598. The Huguenots were led by Jeanne d'Albret

Jeanne d'Albret (, Basque language, Basque: ''Joana Albretekoa''; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Joana de Labrit''; 16 November 1528 – 9 June 1572), also known as Jeanne III, was Queen of Navarre from 1555 to 1572.

Jeanne was the daughter of He ...

; her son, the future Henry IV (who would later convert to Catholicism in order to become king); and the princes of Condé

The Most Serene House of Bourbon-Condé (), named after Condé-en-Brie (now in the Aisne ), was a French princely house and a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon. The name of the house was derived from the title of Prince of Condé (French: '' ...

. The wars ended with the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

of 1598, which granted the Huguenots substantial religious, political and military autonomy.

Huguenot rebellions

The Huguenot rebellions, sometimes called the Rohan Wars after the Huguenot leader Henri, Duke of Rohan, Henri de Rohan, were a series of rebellions of the 1620s in which French people, French Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots), mainly located in ...

in the 1620s resulted in the abolition of their political and military privileges. They retained the religious provisions of the Edict of Nantes until the rule of Louis XIV, who gradually increased persecution of Protestantism until he issued the Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (18 October 1685, published 22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to prac ...

(1685). This ended legal recognition of Protestantism in France

Protestantism in France has existed in its various forms, starting with Calvinism and Lutheranism since the Protestant Reformation. John Calvin was a Frenchman, as were numerous other Protestant Reformers including William Farel, Pierre Viret ...

and the Huguenots were forced to either convert to Catholicism (possibly as Nicodemite

A Nicodemite () is a person suspected of publicly misrepresenting their religious faith to conceal their true beliefs. The term is sometimes defined as referring to a Protestantism, Protestant Christian who lived in a Roman Catholic country and es ...

s) or flee as refugees; they were subject to violent dragonnades. Louis XIV claimed that the French Huguenot population was reduced from about 900,000 or 800,000 adherents to just 1,000 or 1,500. He exaggerated the decline, but the dragonnades were devastating for the French Protestant community. The exodus of Huguenots from France created a brain drain, as many of them had occupied important places in society.

The remaining Huguenots faced continued persecution under Louis XV. By the time of his death in 1774, Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

had been all but eliminated from France. Persecution of Protestants officially ended with the Edict of Versailles

The Edict of Versailles, also known as the Edict of Tolerance, was an official act that gave non-Catholics in France the access to civil rights formerly denied to them, which included the right to contract marriages without having to convert to t ...

, signed by Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

in 1787. Two years later, with the Revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human and civil rights document from the French Revolution; the French title can be translated in the modern era as "Decl ...

of 1789, Protestants gained equal rights as citizens.Aston, ''Religion and Revolution in France, 1780–1804'' (2000) pp. 245–250

Etymology

Besançon Hugues

Besançon Hugues (; 1487 – 1532) was a Swiss political and religious leader who was a member of the Grand Council of Geneva. He participated in the rebellion against the rule of the Savoy dynasty, which led to the independence of Geneva in 15 ...

(died 1532) and the religiously conflicted nature of Swiss republicanism in his time. It used a derogatory pun

A pun, also known as a paronomasia in the context of linguistics, is a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. These ambiguities can arise from t ...

on the name by way of the Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

word (literally 'housemates'), referring to the connotations of a somewhat related word in German ('Confederate' in the sense of 'a citizen of one of the states of the Swiss Confederacy').''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 11th ed, Frank Puaux, ''Huguenot''

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

was John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

's adopted home and the centre of the Calvinist movement. In Geneva, Hugues, though Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, was a leader of the "Confederate Party", so called because it favoured independence from the Duke of Savoy

The titles of the count of Savoy, and then duke of Savoy, are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the House of Savoy held the county. Several of these rulers ruled as kings at ...

. It sought an alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or sovereign state, states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an a ...

between the city-state of Geneva and the Swiss Confederation

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerlan ...

. The label ''Huguenot'' was purportedly first applied in France to those conspirators (all of them aristocratic members of the Reformed Church) who were involved in the Amboise plot of 1560: a foiled attempt to wrest power in France from the influential and zealously Catholic House of Guise

The House of Guise ( , ; ; ) was a prominent French noble family that was involved heavily in the French Wars of Religion. The House of Guise was the founding house of the Principality of Joinville.

Origin

The House of Guise was founded as a c ...

. This action would have fostered relations with the Swiss.

O. I. A. Roche promoted this idea among historians. He wrote in his book, ''The Days of the Upright, A History of the Huguenots'' (1965), that ''Huguenot'' is:

a combination of a Dutch and a German word. In the Dutch-speaking North of France, Bible students who gathered in each other's houses to study secretly were called ("housemates") while on the Swiss and German borders they were termed , or "oath fellows", that is, persons bound to each other by anSome disagree with such non-French linguistic origins. Janet Gray argues that for the word to have spread into common use in France, it must have originated there in French. The "Hugues hypothesis" argues that the name was derived by association with Hugues Capet, king of France, who reigned long before the Reformation. He was regarded by the Gallicians as a noble man who respected people's dignity and lives. Janet Gray and other supporters of the hypothesis suggest that the name would be roughly equivalent to 'little Hugos', or 'those who want Hugo'.oath Traditionally, an oath (from Old English, Anglo-Saxon ', also a plight) is a utterance, statement of fact or a promise taken by a Sacred, sacrality as a sign of Truth, verity. A common legal substitute for those who object to making sacred oaths .... Gallicised into , often used deprecatingly, the word became, during two and a half centuries of terror and triumph, a badge of enduring honour and courage.

Paul Ristelhuber

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo P ...

, in his 1879 introduction to a new edition of the controversial and censored, but popular 1566 work ''Apologie pour Hérodote'', by Henri Estienne

Henri Estienne ( , ; 1528 or 15311598), also known as Henricus Stephanus ( ), was a French printer and classical scholar. He was the eldest son of Robert Estienne. He was instructed in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew by his father and would eventually ...

, mentions these theories and opinions, but tends to support a completely Catholic origin. As one legend holds, a gateway area in the streets of Tours was haunted by the ghosts of (a generic term for these spirits), "because they were wont to assemble near the gate named after Hugon, a Count of Tours in ancient times, who had left a record of evil deeds and had become in popular fancy a sort of sinister and maleficent genius. This count may have been Hugh of Tours

Hugh (or Hugo) ( – 837) was the count of Tours and Sens during the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, until his disgrace in February 828.

Hugh had many possessions in Alsace, as well as the County of Sens. He also held the convent of ...

, who was disliked for his cowardice. Additionally, it is related, that, it was believed, (that of these spirits) instead of spending their time in Purgatory, came back to rattle doors and haunt and harm people at night. Protestants went out at nights to their lascivious conventicles, and so the priests and the people began to call them Huguenots in Tours and then elsewhere." The name, Huguenot, "the people applied in hatred and derision to those who were elsewhere called Lutherans, and from Touraine it spread throughout France." The ('supposedly reformed') were said to gather at night at Tours

Tours ( ; ) is the largest city in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabita ...

, both for political purposes, and for prayer and singing psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

. Reguier de la Plancha (d. 1560) in his offered the following account as to the origin of the name, as cited by ''The Cape Monthly'':

Reguier de la Plancha accounts for itSome have suggested the name was derived, with intended scorn, from (the 'monkeys' or 'apes ofhe name He or HE may refer to: Language * He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads * He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English * He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana) * Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter call ...as follows: "The name was given to those of the religion during the affair of Amboyse, and they were to retain it ever since. I'll say a word about it to settle the doubts of those who have strayed in seeking its origin. The superstition of our ancestors, to within twenty or thirty years thereabouts, was such that in almost all the towns in the kingdom they had a notion that certain spirits underwent their Purgatory in this world after death, and that they went about the town at night, striking and outraging many people whom they found in the streets. But the light of the Gospel has made them vanish, and teaches us that these spirits were street-strollers and ruffians. In Paris the spirit was called ; at Orléans, ; at Blois ; at Tours, ; and so on in other places. Now, it happens that those whom they called Lutherans were at that time so narrowly watched during the day that they were forced to wait till night to assemble, for the purpose of praying God, for preaching and receiving the Holy Sacrament; so that although they did not frighten nor hurt anybody, the priests, through mockery, made them the successors of those spirits which roam the night; and thus that name being quite common in the mouth of the populace, to designate the evangelical in the country of Tourraine and Amboyse, it became in vogue after that enterprise."''De l'Estat de France'' 1560, by Reguier de la Plancha, quoted by ''The Cape Monthly'' (February 1877), No. 82 Vol. XIV on p. 126.

Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1369 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czechs, Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and t ...

'). By 1911, there was still no consensus in the United States on this interpretation.

Symbol

Demographics

Reformed tradition

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteria ...

in France has been covered in a variety of sources. Most of them agree that the Huguenot population reached as many as 10% of the total population, or roughly 2 million people, on the eve of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572.Hans J. Hillerbrand, ''Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set'', paragraphs "France" and "Huguenots"

Links to nobility

The new teaching ofJohn Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

attracted sizeable portions of the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

and urban bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

. After John Calvin introduced the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

in France, the number of French Protestants

Protestantism in France has existed in its various forms, starting with Calvinism and Lutheranism since the Protestant Reformation. John Calvin was a Frenchman, as were numerous other Protestant Reformers including William Farel, Pierre Viret and ...

steadily swelled to ten percent of the population, or roughly 1.8 million people, in the decade between 1560 and 1570. During the same period there were some 1,400 Reformed churches operating in France. Hans J. Hillerbrand, an expert on the subject, in his ''Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set'' claims the Huguenot community reached as much as 10% of the French population on the eve of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre () in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French Wars of Religion. Traditionally believed ...

, declining to 7 to 8% by the end of the 16th century, and further after heavy persecution began once again with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Fontainebleau (18 October 1685, published 22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to pra ...

by Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

in 1685. Among the nobles, Calvinism peaked on the eve of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. Since then, it sharply decreased as the Huguenots were no longer tolerated by both the French royalty and the Catholic masses. By the end of the sixteenth century, Huguenots constituted 7–8% of the whole population, or 1.2 million people. By the time Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

in 1685, Huguenots accounted for 800,000 to 1 million people.

Huguenots controlled sizeable areas in southern and western France. In addition, many areas, especially in the central part of the country, were also contested between the French Reformed and Catholic nobles. Demographically, there were some areas in which the whole populations had been Reformed. These included villages in and around the Massif Central, as well as the area around Dordogne

Dordogne ( , or ; ; ) is a large rural departments of France, department in south west France, with its Prefectures in France, prefecture in Périgueux. Located in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region roughly half-way between the Loire Valley and ...

, which used to be almost entirely Reformed too. John Calvin was a Frenchman and himself largely responsible for the introduction and spread of the Reformed tradition in France. He wrote in French, but unlike the Protestant development in Germany, where Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

writings were widely distributed and could be read by the common man, it was not the case in France, where only nobles adopted the new faith and the folk remained Catholic. This is true for many areas in the west and south controlled by the Huguenot nobility. Although relatively large portions of the peasant population became Reformed there, the people, altogether, still remained majority Catholic.

Overall, Huguenot presence was heavily concentrated in the western and southern portions of the French kingdom, as nobles there secured practise of the new faith. These included Languedoc-Roussillon

Languedoc-Roussillon (; ; ) is a former regions of France, administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, it joined with the region of Midi-Pyrénées to become Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. It comprised five departments o ...

, Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

and even a strip of land that stretched into the Dauphiné

The Dauphiné ( , , ; or ; or ), formerly known in English as Dauphiny, is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was ...

. Huguenots lived on the Atlantic coast in La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle'') is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime Departments of France, department. Wi ...

, and also spread across provinces of Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

and Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

. In the south, towns like Castres

Castres (; ''Castras'' in the Languedocian dialect, Languedocian dialect of Occitan language, Occitan) is the sole Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department in the Occitania (adminis ...

, Montauban

Montauban (, ; ) is a commune in the southern French department of Tarn-et-Garonne. It is the capital of the department and lies north of Toulouse. Montauban is the most populated town in Tarn-et-Garonne, and the sixth most populated of Oc ...

, Montpellier

Montpellier (; ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the Departments of France, department of ...

and Nîmes

Nîmes ( , ; ; Latin: ''Nemausus'') is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Gard Departments of France, department in the Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie Regions of France, region of Southern France. Located between the Med ...

were Huguenot strongholds. In addition, a dense network of Protestant villages permeated the rural mountainous region of the Cevennes. Inhabited by Camisard

Camisards were Huguenots (French Protestants) of the rugged and isolated Cévennes region and the neighbouring Vaunage in southern France. In the early 1700s, they raised a resistance against the persecutions which followed Louis XIV's Revocati ...

s, it continues to be the backbone of French Protestant

Protestantism in France has existed in its various forms, starting with Calvinism and Lutheranism since the Protestant Reformation. John Calvin was a Frenchman, as were numerous other Protestant Reformers including William Farel, Pierre Viret ...

ism. Historians estimate that roughly 80% of all Huguenots lived in the western and southern areas of France.

Today, there are some Reformed communities around the world that still retain their Huguenot identity. In France, Calvinists in the United Protestant Church of France

The United Protestant Church of France () is the main and largest Protestant church in France, created in 2013 through the unification of the Reformed Church of France and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of France. It is active in all parts of ...

and also some in the Protestant Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine

The Protestant Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine ( (EPRAL); ; ) is a Calvinist denomination in Alsace and northeastern Lorraine (the ''Département'' of Moselle), France. As a church body, it enjoys the status as an ''établissement public ...

consider themselves Huguenots. A rural Huguenot community in the Cevennes that rebelled in 1702 is still called ''Camisard

Camisards were Huguenots (French Protestants) of the rugged and isolated Cévennes region and the neighbouring Vaunage in southern France. In the early 1700s, they raised a resistance against the persecutions which followed Louis XIV's Revocati ...

s'', especially in historical contexts. Huguenot exiles in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, and a number of other countries still retain their identity.

Emigration and diaspora

As a final destination, most of the Huguenot émigrés moved to Protestant states such as theDutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

, England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Th ...

(prominently in Kent and London), Protestant-controlled Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, the electorates of Brandenburg

Brandenburg, officially the State of Brandenburg, is a States of Germany, state in northeastern Germany. Brandenburg borders Poland and the states of Berlin, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony. It is the List of Ger ...

and the Palatinate

The Palatinate (; ; Palatine German: ''Palz''), or the Rhenish Palatinate (''Rheinpfalz''), is a historical region of Germany. The Palatinate occupies most of the southern quarter of the German federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate (''Rheinla ...

in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, and the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (, , ) or Ducal Prussia (; ) was a duchy in the region of Prussia established as a result of secularization of the Monastic Prussia, the territory that remained under the control of the State of the Teutonic Order until t ...

. Some fled as refugees to the Dutch Cape Colony

The Cape of Good Hope () was a Dutch United East India Company (VOC) supplystation in Southern Africa, centered on the Cape of Good Hope, from where it derived its name. The original supply station and the successive states that the area was ...

, the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

, various Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

colonies, and several of the Dutch and English colonies in North America. A few families went to Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Catholic Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

.

After centuries, most Huguenots assimilated into the various societies and cultures where they have settled. Remnant communities of Camisard

Camisards were Huguenots (French Protestants) of the rugged and isolated Cévennes region and the neighbouring Vaunage in southern France. In the early 1700s, they raised a resistance against the persecutions which followed Louis XIV's Revocati ...

s in the Cévennes

The Cévennes ( , ; ) is a cultural region and range of mountains in south-central France, on the south-east edge of the Massif Central. It covers parts of the '' départements'' of Ardèche, Gard, Hérault and Lozère. Rich in geographical, ...

, most Reformed members of the United Protestant Church of France

The United Protestant Church of France () is the main and largest Protestant church in France, created in 2013 through the unification of the Reformed Church of France and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of France. It is active in all parts of ...

, French members of the largely German Protestant Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine

The Protestant Reformed Church of Alsace and Lorraine ( (EPRAL); ; ) is a Calvinist denomination in Alsace and northeastern Lorraine (the ''Département'' of Moselle), France. As a church body, it enjoys the status as an ''établissement public ...

, and the Huguenot diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

in England and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, all still retain their beliefs and Huguenot designation.

History

Origins

The availability of the Bible in

The availability of the Bible in vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

languages was important to the spread of the Protestant movement and development of the Reformed Church in France. The country had a long history of struggles with the papacy (see the Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy (; ) was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon (at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire, now part of France) rather than in Rome (now the capital of ...

, for example) by the time the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

finally arrived. Around 1294, a French version of the scriptures was prepared by the Roman Catholic priest, Guyard des Moulins. A two-volume illustrated folio paraphrase version based on his manuscript, by Jean de Rély, was printed in Paris in 1487.

The first known translation of the Bible into one of France's regional languages, Arpitan or Franco-Provençal, had been prepared by the 12th-century pre-Protestant reformer Peter Waldo

Peter Waldo (; also ''Valdo'', ''Valdes'', ''Waldes''; , ''de Vaux''; ; c. 1140 – c. 1205) was the leader of the Waldensians, a Christian spiritual movement of the Middle Ages.

The tradition that his first name was "Peter" can only be traced ...

(Pierre de Vaux). The Waldensians created fortified areas, as in Cabrières, perhaps attacking an abbey.Malcolm D. Lambert, ''Medieval Heresy: Popular Movements from the Gregorian Reform to the Reformation''p. 389 They were suppressed by Francis I in 1545 in the

Massacre of Mérindol

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

.

Other predecessors of the Reformed church included the pro-reform and Gallican Roman Catholics, such as Jacques Lefevre (c. 1455–1536). The Gallicans briefly achieved independence for the French church, on the principle that the religion of France could not be controlled by the Bishop of Rome, a foreign power. During the Protestant Reformation, Lefevre, a professor at the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, published his French translation of the New Testament in 1523, followed by the whole Bible in the French language in 1530. William Farel

William Farel (1489 – 13 September 1565), Guilhem Farel or Guillaume Farel (), was a French evangelist, Protestant reformer and a founder of the Calvinist Church in the Principality of Neuchâtel, in the Republic of Geneva, and in Switzerlan ...

was a student of Lefevre who went on to become a leader of the Swiss Reformation

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli, who gained the support of the magistrate, Mark Reust, and the population of Zürich in the 1520s. It led to significant changes in civil life and state matte ...

, establishing a Protestant republican government in Geneva. Jean Cauvin (John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

), another student at the University of Paris, also converted to Protestantism. Long after the sect was suppressed by Francis I, the remaining French Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

, then mostly in the Luberon

The Luberon ( or ; Provençal dialect, Provençal: ''Leberon'' or ''Leberoun'' ) is a massif in central Provence in Southern France, part of the French Prealps. It has a maximum elevation of and an area of about . It is composed of three mounta ...

region, sought to join Farel, Calvin and the Reformation, and Olivétan published a French Bible for them. The French Confession of 1559 shows a decidedly Calvinistic influence.

Although usually Huguenots are lumped into one group, there were actually two types of Huguenots that emerged. Since the Huguenots had political and religious goals, it was commonplace to refer to the Calvinists as "Huguenots of religion" and those who opposed the monarchy as "Huguenots of the state", who were mostly nobles.

* The Huguenots of religion were influenced by John Calvin's works and established Calvinist synods. They were determined to end religious oppression.

* The Huguenots of the state opposed the monopoly of power the Guise family had and wanted to attack the authority of the crown. This group of Huguenots from southern France had frequent issues with the strict Calvinist tenets that are outlined in many of John Calvin's letters to the synods of the Languedoc.

Reformation and growth

Early in his reign, Francis I () persecuted the old, pre-Protestant movement ofWaldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

in southeastern France. Francis initially protected the Huguenot dissidents from Parlement

Under the French Ancien Régime, a ''parlement'' () was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 ''parlements'', the original and most important of which was the ''Parlement'' of Paris. Though both th ...

ary measures seeking to exterminate them. After the 1534 Affair of the Placards

The Affair of the Placards () was an incident in which anti-Catholic posters appeared in public places in Paris and in four major provincial cities, Blois, Rouen, Tours and Orléans, in the night of the 17 to 18 October 1534. One of the posters ...

, however, he distanced himself from Huguenots and their protection.

Huguenot numbers grew rapidly between 1555 and 1561, chiefly amongst nobles and city dwellers. During this time, their opponents first dubbed the Protestants ''Huguenots''; but they called themselves , or "Reformed". They organised their first national synod in 1558 in Paris.

By 1562, the estimated number of Huguenots peaked at approximately two million, concentrated mainly in the western, southern, and some central parts of France, compared to approximately sixteen million Catholics during the same period. Persecution diminished the number of Huguenots who remained in France.

Wars of religion

As the Huguenots gained influence and displayed their faith more openly, Roman Catholic hostility towards them grew, even though the French crown offered increasingly liberal political concessions and edicts of toleration. Following the accidental death ofHenry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...