Caltech on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a

"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect

. The institute is also occasionally referred to as "CIT", most notably in its alma mater, but this is uncommon. is a private

In 1910, Throop moved to its current site. Arthur Fleming donated the land for the permanent campus site.

In 1910, Throop moved to its current site. Arthur Fleming donated the land for the permanent campus site.  Millikan served as "Chairman of the Executive Council" (effectively Caltech's president) from 1921 to 1945, and his influence was such that the institute was occasionally referred to as "Millikan's School." Millikan initiated a visiting-scholars program soon after joining Caltech. Notable scientists who accepted his invitation include Paul Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Hendrik Lorentz and Niels Bohr.

Millikan served as "Chairman of the Executive Council" (effectively Caltech's president) from 1921 to 1945, and his influence was such that the institute was occasionally referred to as "Millikan's School." Millikan initiated a visiting-scholars program soon after joining Caltech. Notable scientists who accepted his invitation include Paul Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Hendrik Lorentz and Niels Bohr.

From April to December 1951, Caltech was the host of a federal classified study, Project Vista. The selection of Caltech as host for the project was based on the university's expertise in rocketry and nuclear physics. In response to the war in Korea and the pressure from the Soviet Union, the project was Caltech's way of assisting the federal government in its effort to increase national security. The project was created to study new ways of improving the relationship between tactical air support and ground troops. The Army, Air Force, and Navy sponsored the project; however, it was under contract with the Army. The study was named after the hotel, Vista del Arroyo Hotel, which housed the study. The study operated under a committee with the supervision of President

From April to December 1951, Caltech was the host of a federal classified study, Project Vista. The selection of Caltech as host for the project was based on the university's expertise in rocketry and nuclear physics. In response to the war in Korea and the pressure from the Soviet Union, the project was Caltech's way of assisting the federal government in its effort to increase national security. The project was created to study new ways of improving the relationship between tactical air support and ground troops. The Army, Air Force, and Navy sponsored the project; however, it was under contract with the Army. The study was named after the hotel, Vista del Arroyo Hotel, which housed the study. The study operated under a committee with the supervision of President

In fall 2008, the freshman class was 42% female, a record for Caltech's undergraduate enrollment. In the same year, the Institute concluded a six-year-long fund-raising campaign. The campaign raised more than $1.4 billion from about 16,000 donors. Nearly half of the funds went into the support of Caltech programs and projects.

In 2010, Caltech, in partnership with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and headed by Professor Nathan Lewis, established a DOE Energy Innovation Hub aimed at developing revolutionary methods to generate fuels directly from sunlight. This hub, the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis, will receive up to $122 million in federal funding over five years.

Since 2012, Caltech began to offer classes through massive open online courses (MOOCs) under

In fall 2008, the freshman class was 42% female, a record for Caltech's undergraduate enrollment. In the same year, the Institute concluded a six-year-long fund-raising campaign. The campaign raised more than $1.4 billion from about 16,000 donors. Nearly half of the funds went into the support of Caltech programs and projects.

In 2010, Caltech, in partnership with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and headed by Professor Nathan Lewis, established a DOE Energy Innovation Hub aimed at developing revolutionary methods to generate fuels directly from sunlight. This hub, the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis, will receive up to $122 million in federal funding over five years.

Since 2012, Caltech began to offer classes through massive open online courses (MOOCs) under

Caltech's primary campus is located in Pasadena, California, approximately northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is within walking distance of Old Town Pasadena and the Pasadena Playhouse District and therefore the two locations are frequent getaways for Caltech students.

In 1917 Hale hired architect Bertram Goodhue to produce a master plan for the campus. Goodhue conceived the overall layout of the campus and designed the physics building, Dabney Hall, and several other structures, in which he sought to be consistent with the local climate, the character of the school, and Hale's educational philosophy. Goodhue's designs for Caltech were also influenced by the traditional

Caltech's primary campus is located in Pasadena, California, approximately northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is within walking distance of Old Town Pasadena and the Pasadena Playhouse District and therefore the two locations are frequent getaways for Caltech students.

In 1917 Hale hired architect Bertram Goodhue to produce a master plan for the campus. Goodhue conceived the overall layout of the campus and designed the physics building, Dabney Hall, and several other structures, in which he sought to be consistent with the local climate, the character of the school, and Hale's educational philosophy. Goodhue's designs for Caltech were also influenced by the traditional

During the 1960s, Caltech underwent considerable expansion, in part due to the philanthropy of alumnus Arnold O. Beckman. In 1953, Beckman was asked to join the Caltech Board of Trustees. In 1964, he became its chairman. Over the next few years, as Caltech's president emeritus

During the 1960s, Caltech underwent considerable expansion, in part due to the philanthropy of alumnus Arnold O. Beckman. In 1953, Beckman was asked to join the Caltech Board of Trustees. In 1964, he became its chairman. Over the next few years, as Caltech's president emeritus

"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect

. The institute is also occasionally referred to as "CIT", most notably in its alma mater, but this is uncommon. is a private

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kno ...

in Pasadena, California. Caltech is ranked among the best and most selective academic institutions in the world, and with an enrollment of approximately 2400 students (acceptance rate of only 5.7%), it is one of the world's most selective universities. The university is known for its strength in science and engineering, and is among a small group of institutes of technology in the United States which is primarily devoted to the instruction of pure and applied sciences.

The institution was founded as a preparatory and vocational school by Amos G. Throop in 1891 and began attracting influential scientists such as George Ellery Hale, Arthur Amos Noyes

Arthur Amos Noyes (September 13, 1866 – June 3, 1936) was an American chemist, inventor and educator. He received a PhD in 1890 from Leipzig University under the guidance of Wilhelm Ostwald.

He served as the acting president of MIT between ...

, and Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectri ...

in the early 20th century. The vocational and preparatory schools were disbanded and spun off in 1910 and the college assumed its present name in 1920. In 1934, Caltech was elected to the Association of American Universities, and the antecedents of NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedi ...

's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is a federally funded research and development center and NASA field center in the City of La Cañada Flintridge, California, United States.

Founded in the 1930s by Caltech researchers, JPL is owned by NASA ...

, which Caltech continues to manage and operate, were established between 1936 and 1943 under Theodore von Kármán.

Caltech has six academic divisions with strong emphasis on science and engineering, managing $332 million in 2011 in sponsored research. Its primary campus is located approximately northeast of downtown Los Angeles. First-year students are required to live on campus, and 95% of undergraduates remain in the on-campus House System at Caltech. Although Caltech has a strong tradition of practical jokes and pranks, student life is governed by an honor code which allows faculty to assign take-home examinations. The Caltech Beavers compete in 13 intercollegiate sports in the NCAA

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges and ...

Division III's Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SCIAC).

Scientists and engineers at or from the university have played an essential role in many modern scientific breakthroughs and innovations, including advancements in sustainability science, quantum physics, earthquake monitoring, protein engineering, and soft robotics. , there are 79 Nobel laureates who have been affiliated with Caltech, including 46 alumni and faculty members (47 prizes, with chemist Linus Pauling being the only individual in history to win two unshared prizes); in addition, 4 Fields Medalists and 6 Turing Award winners have been affiliated with Caltech. There are 8 Crafoord Laureates and 56 non-emeritus faculty members (as well as many emeritus faculty members) who have been elected to one of the United States National Academies, 4 Chief Scientists of the U.S. Air Force and 71 have won the United States National Medal of Science or Technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scie ...

. Numerous faculty members are associated with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute as well as NASA. According to a 2015 Pomona College study, Caltech ranked number one in the U.S. for the percentage of its graduates who go on to earn a PhD.

History

Throop College

Caltech started as a vocational school founded in present-dayOld Pasadena

Old Pasadena, often referred to as Old Town Pasadena or just Old Town, is the original commercial center of Pasadena, a city in California, United States, and had a latter-day revitalization after a period of decay.

Old Pasadena began as the ...

on Fair Oaks Avenue and Chestnut Street on September 23, 1891, by local businessman and politician Amos G. Throop. The school was known successively as Throop University, Throop Polytechnic Institute (and Manual Training School) and Throop College of Technology before acquiring its current name in 1920. The vocational school was disbanded and the preparatory program was split off to form the independent Polytechnic School in 1907.

At a time when scientific research in the United States was still in its infancy, George Ellery Hale, a solar astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either o ...

from the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, founded the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1904. He joined Throop's board of trustees in 1907, and soon began developing it and the whole of Pasadena into a major scientific and cultural destination. He engineered the appointment of James A. B. Scherer, a literary scholar untutored in science but a capable administrator and fund-raiser, to Throop's presidency in 1908. Scherer persuaded retired businessman and trustee Charles W. Gates to donate $25,000 in seed money to build Gates Laboratory, the first science building on campus.

World Wars

In 1910, Throop moved to its current site. Arthur Fleming donated the land for the permanent campus site.

In 1910, Throop moved to its current site. Arthur Fleming donated the land for the permanent campus site. Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

delivered an address at Throop Institute on March 21, 1911, and he declared:

I want to see institutions like Throop turn out perhaps ninety-nine of every hundred students as men who are to do given pieces of industrial work better than any one else can do them; I want to see those men do the kind of work that is now being done on theIn the same year, a bill was introduced in the California Legislature calling for the establishment of a publicly funded "California Institute of Technology", with an initial budget of a million dollars, ten times the budget of Throop at the time. The board of trustees offered to turn Throop over to the state, but the presidents of Stanford University and the University of California successfully lobbied to defeat the bill, which allowed Throop to develop as the only scientific research-oriented education institute in southern California, public or private, until the onset of the World War II necessitated the broader development of research-based science education. The promise of Throop attracted physical chemistPanama Canal The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a Channel ( ...and on the great irrigation projects in the interior of this country—and the one-hundredth man I want to see with the kind of cultural scientific training that will make him and his fellows the matrix out of which you can occasionally develop a man like your great astronomer, George Ellery Hale.

Arthur Amos Noyes

Arthur Amos Noyes (September 13, 1866 – June 3, 1936) was an American chemist, inventor and educator. He received a PhD in 1890 from Leipzig University under the guidance of Wilhelm Ostwald.

He served as the acting president of MIT between ...

from MIT to develop the institution and assist in establishing it as a center for science and technology.

With the onset of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Hale organized the National Research Council to coordinate and support scientific work on military problems. While he supported the idea of federal appropriations for science, he took exception to a federal bill that would have funded engineering research at land-grant colleges, and instead sought to raise a $1 million national research fund entirely from private sources. To that end, as Hale wrote in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'':

Throop College of Technology, in Pasadena California has recently afforded a striking illustration of one way in which the Research Council can secure co-operation and advance scientific investigation. This institution, with its able investigators and excellent research laboratories, could be of great service in any broad scheme of cooperation. President Scherer, hearing of the formation of the council, immediately offered to take part in its work, and with this object, he secured within three days an additional research endowment of one hundred thousand dollars.Through the National Research Council, Hale simultaneously lobbied for science to play a larger role in national affairs, and for Throop to play a national role in science. The new funds were designated for physics research, and ultimately led to the establishment of the Norman Bridge Laboratory, which attracted experimental

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate ca ...

Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectri ...

from the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

in 1917. During the course of the war, Hale, Noyes and Millikan worked together in Washington on the NRC. Subsequently, they continued their partnership in developing Caltech.

Under the leadership of Hale, Noyes

Noyes is an English surname of patronymic origin, deriving from the given name Noah. Notable people with the surname include:

* Albertina Noyes (born 1949), American figure skater

* Alfred Noyes (1880–1958), English poet

* Arthur Amos Noyes (18 ...

, and Millikan (aided by the booming economy of Southern California), Caltech grew to national prominence in the 1920s and concentrated on the development of Roosevelt's "Hundredth Man". On November 29, 1921, the trustees declared it to be the express policy of the institute to pursue scientific research of the greatest importance and at the same time "to continue to conduct thorough courses in engineering and pure science, basing the work of these courses on exceptionally strong instruction in the fundamental sciences of mathematics, physics, and chemistry; broadening and enriching the curriculum by a liberal amount of instruction in such subjects as English, history, and economics; and vitalizing all the work of the Institute by the infusion in generous measure of the spirit of research". In 1923, Millikan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

. In 1925, the school established a department of geology and hired William Bennett Munro

William Bennett Munro (5 January 1875 – 4 September 1957) was a Canadian historian and political scientist. He taught at Harvard University and the California Institute of Technology. He was known for research on the seigneurial system in New Fr ...

, then chairman of the division of History, Government, and Economics at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, to create a division of humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

and social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soc ...

s at Caltech. In 1928, a division of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

was established under the leadership of Thomas Hunt Morgan, the most distinguished biologist in the United States at the time, and discoverer of the role of genes and the chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

in heredity. In 1930, Kerckhoff Marine Laboratory was established in Corona del Mar under the care of Professor George MacGinitie. In 1926, a graduate school of aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identif ...

was created, which eventually attracted Theodore von Kármán. Kármán later helped create the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and played an integral part in establishing Caltech as one of the world's centers for rocket science. In 1928, construction of the Palomar Observatory began.

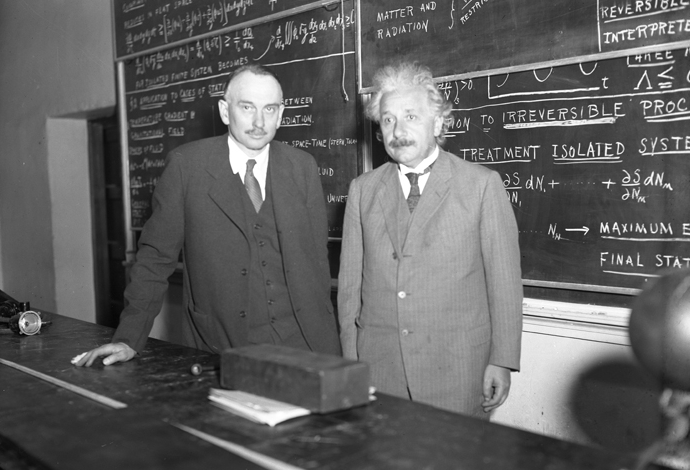

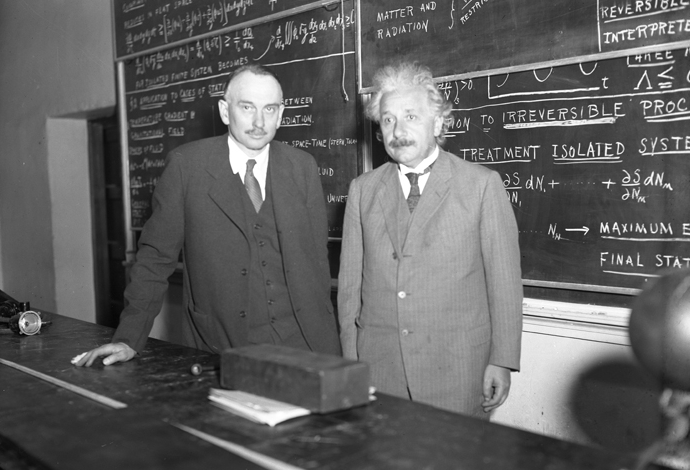

Millikan served as "Chairman of the Executive Council" (effectively Caltech's president) from 1921 to 1945, and his influence was such that the institute was occasionally referred to as "Millikan's School." Millikan initiated a visiting-scholars program soon after joining Caltech. Notable scientists who accepted his invitation include Paul Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Hendrik Lorentz and Niels Bohr.

Millikan served as "Chairman of the Executive Council" (effectively Caltech's president) from 1921 to 1945, and his influence was such that the institute was occasionally referred to as "Millikan's School." Millikan initiated a visiting-scholars program soon after joining Caltech. Notable scientists who accepted his invitation include Paul Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, Hendrik Lorentz and Niels Bohr. Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

arrived on the Caltech campus for the first time in 1931 to polish up his Theory of General Relativity, and he returned to Caltech subsequently as a visiting professor in 1932 and 1933.

During World War II, Caltech was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission. The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

also maintained a naval training school for aeronautical engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is sim ...

, resident inspectors of ordinance and naval material, and a liaison officer to the National Defense Research Committee on campus.

Project Vista

From April to December 1951, Caltech was the host of a federal classified study, Project Vista. The selection of Caltech as host for the project was based on the university's expertise in rocketry and nuclear physics. In response to the war in Korea and the pressure from the Soviet Union, the project was Caltech's way of assisting the federal government in its effort to increase national security. The project was created to study new ways of improving the relationship between tactical air support and ground troops. The Army, Air Force, and Navy sponsored the project; however, it was under contract with the Army. The study was named after the hotel, Vista del Arroyo Hotel, which housed the study. The study operated under a committee with the supervision of President

From April to December 1951, Caltech was the host of a federal classified study, Project Vista. The selection of Caltech as host for the project was based on the university's expertise in rocketry and nuclear physics. In response to the war in Korea and the pressure from the Soviet Union, the project was Caltech's way of assisting the federal government in its effort to increase national security. The project was created to study new ways of improving the relationship between tactical air support and ground troops. The Army, Air Force, and Navy sponsored the project; however, it was under contract with the Army. The study was named after the hotel, Vista del Arroyo Hotel, which housed the study. The study operated under a committee with the supervision of President Lee A. DuBridge

Lee Alvin DuBridge () was an American educator and physicist, best known as president of the California Institute of Technology from 1946–1969.

Background

Lee Alvin DuBridge was born on , in Terre Haute, Indiana. His father was Fred DuBridge, ...

. William A. Fowler, a professor at Caltech, was selected as research director. More than a fourth of Caltech's faculty and a group of outside scientists staffed the project. Moreover, the number increases if one takes into account visiting scientists, military liaisons, secretarial, and security staff. In compensation for its participation, the university received about $750,000.

Post-war growth

From the 1950s to 1980s, Caltech was the home of Murray Gell-Mann and Richard Feynman, whose work was central to the establishment of theStandard Model

The Standard Model of particle physics is the theory describing three of the four known fundamental forces ( electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions - excluding gravity) in the universe and classifying all known elementary particles. I ...

of particle physics. Feynman was also widely known outside the physics community as an exceptional teacher and a colorful, unconventional character.

During Lee A. DuBridge

Lee Alvin DuBridge () was an American educator and physicist, best known as president of the California Institute of Technology from 1946–1969.

Background

Lee Alvin DuBridge was born on , in Terre Haute, Indiana. His father was Fred DuBridge, ...

's tenure as Caltech's president (1946–1969), Caltech's faculty doubled and the campus tripled in size. DuBridge, unlike his predecessors, welcomed federal funding of science. New research fields flourished, including chemical biology, planetary science, nuclear astrophysics, and geochemistry

Geochemistry is the science that uses the tools and principles of chemistry to explain the mechanisms behind major geological systems such as the Earth's crust and its oceans. The realm of geochemistry extends beyond the Earth, encompassing the ...

. A 200-inch telescope was dedicated on nearby Palomar Mountain in 1948 and remained the world's most powerful optical telescope for over forty years.

Caltech opened its doors to female undergraduates during the presidency of Harold Brown in 1970, and they made up 14% of the entering class. The portion of female undergraduates has been increasing since then.

Protests by Caltech students are rare. The earliest was a 1968 protest outside the NBC Burbank studios, in response to rumors that NBC was to cancel '' Star Trek''. In 1973, the students from Dabney House protested a presidential visit with a sign on the library bearing the simple phrase " Impeach Nixon". The following week, Ross McCollum, president of the National Oil Company, wrote an open letter to Dabney House stating that in light of their actions he had decided not to donate one million dollars to Caltech. The Dabney family, being Republicans, disowned Dabney House after hearing of the protest.

21st century

Since 2000, theEinstein Papers Project

The Einstein Papers Project (EPP) produces the historical edition of the writings and correspondence of Albert Einstein. The EPP collects, transcribes, translates, annotates, and publishes materials from Einstein's literary estate and a multitude ...

has been located at Caltech. The project was established in 1986 to assemble, preserve, translate, and publish papers selected from the literary estate of Albert Einstein and from other collections.

In fall 2008, the freshman class was 42% female, a record for Caltech's undergraduate enrollment. In the same year, the Institute concluded a six-year-long fund-raising campaign. The campaign raised more than $1.4 billion from about 16,000 donors. Nearly half of the funds went into the support of Caltech programs and projects.

In 2010, Caltech, in partnership with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and headed by Professor Nathan Lewis, established a DOE Energy Innovation Hub aimed at developing revolutionary methods to generate fuels directly from sunlight. This hub, the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis, will receive up to $122 million in federal funding over five years.

Since 2012, Caltech began to offer classes through massive open online courses (MOOCs) under

In fall 2008, the freshman class was 42% female, a record for Caltech's undergraduate enrollment. In the same year, the Institute concluded a six-year-long fund-raising campaign. The campaign raised more than $1.4 billion from about 16,000 donors. Nearly half of the funds went into the support of Caltech programs and projects.

In 2010, Caltech, in partnership with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and headed by Professor Nathan Lewis, established a DOE Energy Innovation Hub aimed at developing revolutionary methods to generate fuels directly from sunlight. This hub, the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis, will receive up to $122 million in federal funding over five years.

Since 2012, Caltech began to offer classes through massive open online courses (MOOCs) under Coursera

Coursera Inc. () is a U.S.-based massive open online course provider founded in 2012 by Stanford University computer science professors Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller. Coursera works with universities and other organizations to offer online cour ...

, and from 2013, edX.

Jean-Lou Chameau, the eighth president, announced on February 19, 2013, that he would be stepping down to accept the presidency at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. Thomas F. Rosenbaum

Thomas Felix Rosenbaum (born February 20, 1955) is an American physicist and the current President of the California Institute of Technology. Earlier he served as Provost and on the faculty of the University of Chicago, and was the Vice Presi ...

was announced to be the ninth president of Caltech on October 24, 2013, and his term began on July 1, 2014.

In 2019, Caltech received a gift of $750 million for sustainability research from the Resnick family of The Wonderful Company. The gift is the largest ever for environmental sustainability research and the second-largest private donation to a US academic institution (after Bloomberg's gift of $1.8 billion to Johns Hopkins University in 2018).

On account of President Robert A. Millikan's affiliation with the Human Betterment Foundation, in January 2021, the Caltech Board of Trustees authorized the removal of Millikan's name (and the names of five other historical figures affiliated with the Foundation), from campus buildings.

Campus

Caltech's primary campus is located in Pasadena, California, approximately northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is within walking distance of Old Town Pasadena and the Pasadena Playhouse District and therefore the two locations are frequent getaways for Caltech students.

In 1917 Hale hired architect Bertram Goodhue to produce a master plan for the campus. Goodhue conceived the overall layout of the campus and designed the physics building, Dabney Hall, and several other structures, in which he sought to be consistent with the local climate, the character of the school, and Hale's educational philosophy. Goodhue's designs for Caltech were also influenced by the traditional

Caltech's primary campus is located in Pasadena, California, approximately northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is within walking distance of Old Town Pasadena and the Pasadena Playhouse District and therefore the two locations are frequent getaways for Caltech students.

In 1917 Hale hired architect Bertram Goodhue to produce a master plan for the campus. Goodhue conceived the overall layout of the campus and designed the physics building, Dabney Hall, and several other structures, in which he sought to be consistent with the local climate, the character of the school, and Hale's educational philosophy. Goodhue's designs for Caltech were also influenced by the traditional Spanish mission architecture

The Mission Revival style was part of an architectural movement, beginning in the late 19th century, for the revival and reinterpretation of American colonial styles. Mission Revival drew inspiration from the late 18th and early 19th century ...

of Southern California.

During the 1960s, Caltech underwent considerable expansion, in part due to the philanthropy of alumnus Arnold O. Beckman. In 1953, Beckman was asked to join the Caltech Board of Trustees. In 1964, he became its chairman. Over the next few years, as Caltech's president emeritus

During the 1960s, Caltech underwent considerable expansion, in part due to the philanthropy of alumnus Arnold O. Beckman. In 1953, Beckman was asked to join the Caltech Board of Trustees. In 1964, he became its chairman. Over the next few years, as Caltech's president emeritus