Caloenas Maculata on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The spotted green pigeon or Liverpool pigeon (''Caloenas maculata'') is a

The spotted green pigeon was first mentioned and described by the English ornithologist John Latham in his 1783 work ''A General Synopsis of Birds''. Latham stated that he had seen two specimens, in the collections of the English major Thomas Davies and the naturalist

The spotted green pigeon was first mentioned and described by the English ornithologist John Latham in his 1783 work ''A General Synopsis of Birds''. Latham stated that he had seen two specimens, in the collections of the English major Thomas Davies and the naturalist

The spotted green pigeon was shown to be closest to the Nicobar pigeon. The

The spotted green pigeon was shown to be closest to the Nicobar pigeon. The

Latham's 1823 description of the spotted green pigeon from ''A General History of Birds'' (expanded from the one in ''A General Synopsis of Birds'') reads as follows:

Most literature addressing the spotted green pigeon simply repeated Latham's descriptions, adding little new information, until Gibbs published a more detailed description in 2001, followed by the museum curator Hein van Grouw in 2014. The surviving specimen measures in length, though study specimens are often stretched or compressed during taxidermy, and may therefore not reflect the length of a living bird. The weight has not been recorded. The spotted green pigeon appears to have been smaller and slenderer than the Nicobar pigeon, which reaches , and the Kanaka pigeon appears to have been 25% larger than the latter. At in length, the tail is longer than that of the Nicobar pigeon, but the head is smaller in relation. The bill is , and the tarsus measures . Though the wings of the specimen appear to be short and rounded, and have been described as being long, vanGrouw discovered that the five outer

Latham's 1823 description of the spotted green pigeon from ''A General History of Birds'' (expanded from the one in ''A General Synopsis of Birds'') reads as follows:

Most literature addressing the spotted green pigeon simply repeated Latham's descriptions, adding little new information, until Gibbs published a more detailed description in 2001, followed by the museum curator Hein van Grouw in 2014. The surviving specimen measures in length, though study specimens are often stretched or compressed during taxidermy, and may therefore not reflect the length of a living bird. The weight has not been recorded. The spotted green pigeon appears to have been smaller and slenderer than the Nicobar pigeon, which reaches , and the Kanaka pigeon appears to have been 25% larger than the latter. At in length, the tail is longer than that of the Nicobar pigeon, but the head is smaller in relation. The bill is , and the tarsus measures . Though the wings of the specimen appear to be short and rounded, and have been described as being long, vanGrouw discovered that the five outer  The bill of the specimen is black with a yellowish tip, and the

The bill of the specimen is black with a yellowish tip, and the  When examining the specimen, van Grouw noticed that the legs had at one point been detached and are now attached opposite their natural positions. The short feathering of the legs would therefore have been attached to the inner side of the upper tarsus in life, not the outer. The plate accompanying Forbes' 1898 article shows the feathers on the outer side, and depicts the legs as pinkish, whereas they are yellow in the skin. The spotted green pigeon has at times been described as having a knob at the base of its bill, similar to that of the Nicobar pigeon. This idea seems to have originated with Forbes, who had the bird depicted with this feature, perhaps due to his conviction that it was a species of ''Caloenas''; it was depicted with a knob as late as 2002. This is despite the fact that the surviving specimen does not possess a knob, and Latham did not mention or depict this feature, so such depictions are probably incorrect. The artificial eyes of the specimen were removed when it was prepared into a study skin, but red paint around the right eye-socket suggests that it was originally intended to have red eyes. It is unknown whether this represents the natural eye colour of the bird, yet the eyes were also depicted as red in Latham's illustration, which does not appear to have been based on the existing specimen. Forbes had the iris depicted as orange and the skin around the eye as green, though this was probably guesswork.

The triangular spots of the spotted green pigeon are not unique among pigeons, but are also seen in the spot-winged pigeon (''Columba maculosa'') and the

When examining the specimen, van Grouw noticed that the legs had at one point been detached and are now attached opposite their natural positions. The short feathering of the legs would therefore have been attached to the inner side of the upper tarsus in life, not the outer. The plate accompanying Forbes' 1898 article shows the feathers on the outer side, and depicts the legs as pinkish, whereas they are yellow in the skin. The spotted green pigeon has at times been described as having a knob at the base of its bill, similar to that of the Nicobar pigeon. This idea seems to have originated with Forbes, who had the bird depicted with this feature, perhaps due to his conviction that it was a species of ''Caloenas''; it was depicted with a knob as late as 2002. This is despite the fact that the surviving specimen does not possess a knob, and Latham did not mention or depict this feature, so such depictions are probably incorrect. The artificial eyes of the specimen were removed when it was prepared into a study skin, but red paint around the right eye-socket suggests that it was originally intended to have red eyes. It is unknown whether this represents the natural eye colour of the bird, yet the eyes were also depicted as red in Latham's illustration, which does not appear to have been based on the existing specimen. Forbes had the iris depicted as orange and the skin around the eye as green, though this was probably guesswork.

The triangular spots of the spotted green pigeon are not unique among pigeons, but are also seen in the spot-winged pigeon (''Columba maculosa'') and the

The behaviour of the spotted green pigeon was not recorded, but theories have been proposed based on its physical features. Gibbs found the delicate, part-feathered legs and long tail indicative of at least partially arboreal habits. After noting that the wings were not short after all, van Grouw stated that the bird would not have been terrestrial, unlike the related Nicobar pigeon. He pointed out that the overall proportions and shape of the bird (longer tail, shorter legs, primary feathers probably reaching the middle of the tail) was more similar to the pigeons of the genus ''Ducula''. It may therefore have been ecologically similar to those birds, have likewise been strongly arboreal, and kept to the dense

The behaviour of the spotted green pigeon was not recorded, but theories have been proposed based on its physical features. Gibbs found the delicate, part-feathered legs and long tail indicative of at least partially arboreal habits. After noting that the wings were not short after all, van Grouw stated that the bird would not have been terrestrial, unlike the related Nicobar pigeon. He pointed out that the overall proportions and shape of the bird (longer tail, shorter legs, primary feathers probably reaching the middle of the tail) was more similar to the pigeons of the genus ''Ducula''. It may therefore have been ecologically similar to those birds, have likewise been strongly arboreal, and kept to the dense

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of pigeon

Columbidae is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with small heads, relatively short necks and slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. ...

which is most likely extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

. It was first mentioned and described in 1783 by John Latham, who had seen two specimens of unknown provenance

Provenance () is the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object. The term was originally mostly used in relation to works of art, but is now used in similar senses in a wide range of fields, including archaeology, p ...

and a drawing depicting the bird. The taxonomic

280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme of classes (a taxonomy) and the allocation ...

relationships of the bird were long obscure, and early writers suggested many different possibilities, though the idea that it was related to the Nicobar pigeon

The Nicobar pigeon or Nicobar dove (''Caloenas nicobarica'', Car: ') is a bird found on small islands and in coastal regions from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India, east through the Indonesian Archipelago, to the Solomons and Palau. It is ...

(''C. nicobarica'') prevailed, and it was therefore placed in the same genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

, '' Caloenas''. Today, the species is only known from a specimen kept in World Museum, Liverpool

World Museum is a large museum in Liverpool, England which has extensive collections covering archaeology, ethnology and the natural and physical sciences. Special attractions include the Natural History Centre and a planetarium. Entry to the ...

. Overlooked for much of the 20th century, it was recognised as a valid extinct species by the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological ...

only in 2008. It may have been native to an island somewhere in the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

or the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, and it has been suggested that a bird referred to as ''titi'' by Tahitian islanders was this bird. In 2014, a genetic study confirmed it as a distinct species related to the Nicobar pigeon, and showed that the two were the closest relatives of the extinct dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

and Rodrigues solitaire

The Rodrigues solitaire (''Pezophaps solitaria'') is an extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Rodrigues, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Genetically within the family of Columbidae, pigeons and doves, it wa ...

.

The surviving specimen is long, and has very dark, brownish plumage

Plumage () is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, there can b ...

with a green gloss. The neck feathers are elongated, and most of the feathers on the upperparts and wings have a yellowish spot on their tips. It has a black bill with a yellow tip, and the end of the tail has a pale band. It has relatively short legs and long wings. It has been suggested it had a knob on its bill, but there is no evidence for this. Unlike the Nicobar pigeon, which is mainly terrestrial, the physical features of the spotted green pigeon suggest it was mainly arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

, and fed on fruits. The spotted green pigeon may have been close to extinction by the time Europeans arrived in its native area, and may have disappeared due to over-hunting and predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

by introduced animals around the 1820s.

Taxonomy

The spotted green pigeon was first mentioned and described by the English ornithologist John Latham in his 1783 work ''A General Synopsis of Birds''. Latham stated that he had seen two specimens, in the collections of the English major Thomas Davies and the naturalist

The spotted green pigeon was first mentioned and described by the English ornithologist John Latham in his 1783 work ''A General Synopsis of Birds''. Latham stated that he had seen two specimens, in the collections of the English major Thomas Davies and the naturalist Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

, but it is uncertain how these ended up in the respective collections, and their provenance

Provenance () is the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object. The term was originally mostly used in relation to works of art, but is now used in similar senses in a wide range of fields, including archaeology, p ...

is unknown. Though Banks received many specimens from the British explorer James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

, and Davies received specimens from contacts in New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

, implying a location in the South Pacific Ocean

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, there are no records of spotted green pigeons having been sent from these sources. After Davies' death, his specimen was bought in 1812 by Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby

Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby (21 April 1775 – 30 June 1851), styled Lord Stanley from 1776 to 1832, and Baron Stanley of Bickerstaffe from 1832–4, was an English politician, peer, landowner, builder, farmer, art collector and na ...

, who kept it in Knowsley Hall

Knowsley Hall is a stately home near Liverpool in the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley, Merseyside, England. It is the ancestral home of the Stanley family, the Earls of Derby. The hall is surrounded by of parkland, which contains the Knowsley S ...

. Smith-Stanley's collection was transferred to the Derby Museum in 1851, where the specimen was prepared from the original posed mount (which had perhaps been taxidermised by Davies himself) into a study skin. This museum later became World Museum

World Museum is a large museum in Liverpool, England which has extensive collections covering archaeology, ethnology and the natural and physical sciences. Special attractions include the Natural History Centre and a planetarium. Entry to the ...

, where the specimen is housed today, but Banks' specimen is now lost. Latham also mentioned a drawing of a spotted green pigeon in the collection of the British antiquarian Ashton Lever

Sir Ashton Lever FRS (5 March 1729 – 28 January 1788) was an English collector of natural objects, in particular the Leverian collection., Manchester celebrities], retrieved 31 August 2010

Biography

Lever was born in 1729 at Alkrington, A ...

, but it is unknown which specimen this was based on; it could have been either, or a third individual. Latham included an illustration of the spotted green pigeon in his 1823 work ''A General History of Birds'', and though the basis for his illustration is unknown, it differs from Davies' specimen in some details. It is possible that it was based on the drawing in the Leverian collection

The Leverian collection was a natural history and ethnographic collection assembled by Ashton Lever. It was noted for the content it acquired from the voyages of Captain James Cook. For three decades it was displayed in London, being broken up ...

, since Latham stated that this drawing showed the end of the tail as "deep ferruginous" (rust-coloured), a feature also depicted in his own illustration.

The spotted green pigeon was scientifically named by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin

Johann Friedrich Gmelin (8 August 1748 – 1 November 1804) was a German natural history, naturalist, chemist, botanist, entomologist, herpetologist, and malacologist.

Education

Johann Friedrich Gmelin was born as the eldest son of Philipp F ...

in 1789, based on Latham's description. The original binomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

''Columba maculata'' means "spotted pigeon" in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. Latham himself accepted this name, and used it in his 1790 work ''Index ornithologicus''. Since Latham appears to have based his 1783 description on Davies' specimen, this can therefore be considered the holotype specimen

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was Species description, formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illus ...

of the species. Subsequent writers were uncertain about the validity and relationships of the species; the English naturalist James Francis Stephens

James Francis Stephens (16 September 1792 – 22 December 1852) was an England, English entomologist and naturalist. He is known for his 12 volume ''Illustrations of British Entomology'' (1846) and the ''Manual of British Beetles'' (1839).

...

suggested that it belonged in the fruit pigeon genus ''Ptilinopus

The fruit doves, also known as fruit pigeons, are a genus (''Ptilinopus'') of birds in the pigeon and dove family (Columbidae). These colourful, frugivorous doves are found in forests and woodlands in Southeast Asia and Oceania. It is a large gen ...

'' in 1826, and the German ornithologist Johann Georg Wagler

Johann Georg Wagler (28 March 1800 – 23 August 1832) was a German herpetologist and ornithologist.

Wagler was assistant to Johann Baptist von Spix, and gave lectures in zoology at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich after it was moved t ...

instead suggested that it was a juvenile Nicobar pigeon

The Nicobar pigeon or Nicobar dove (''Caloenas nicobarica'', Car: ') is a bird found on small islands and in coastal regions from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India, east through the Indonesian Archipelago, to the Solomons and Palau. It is ...

(''Caloenas nicobarica'') in 1827. The Italian zoologist Tommaso Salvadori

Count Adelardo Tommaso Salvadori Paleotti (30 September 1835 – 9 October 1923) was an Italian zoologist and ornithologist.

Biography

Salvadori was born in Porto San Giorgio, son of Count Luigi Salvadori and Ethelyn Welby, who was English. His ...

listed the bird in an appendix about "doubtful species of pigeons, which have not yet been identified" in 1893. In 1898, the Scottish ornithologist Henry Ogg Forbes

Henry Ogg Forbes (30 January 1851 – 27 October 1932) was a Scottish explorer, ornithologist, and botanist. He also described a new species of spider, '' Thomisus decipiens''.

Biography

Forbes was the son of Rev Alexander Forbes M.A. (1821� ...

supported the validity of the species, after examining Nicobar pigeon specimens and concluding that none resembled the spotted green pigeon at any stage of development. He therefore considered it a distinct species of the same genus as the Nicobar pigeon, ''Caloenas''. In 1901, the British zoologist Walter Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoologist, and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he was present ...

and the German ornithologist Ernst Hartert

Ernst Johann Otto Hartert (29 October 1859 – 11 November 1933) was a widely published German ornithologist.

Life and career

Hartert was born in the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg on 29 October 1859. In July 1891, he married the illustrat ...

agreed that the pigeon belonged to ''Caloenas'', but suggested that it was probably an "abnormity", though more than one specimen had been recorded.

The spotted green pigeon was only sporadically mentioned in the literature throughout the 20th century; little new information was published, and the bird remained an enigma. In 2001, the English writer Errol Fuller suggested that the bird had been historically overlooked because Rothschild (an avid collector of rare birds) dismissed it as an aberration, perhaps because he did not own the surviving specimen himself. Fuller considered it a valid, extinct species, and also coined an alternative common name for the bird: the Liverpool pigeon. On the basis of Fuller's endorsement, BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

listed the spotted green pigeon as "Extinct" on the IUCN Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological ...

in 2008; it was previously "Not Recognized". In 2001, the British ornithologist David Gibbs stated that the spotted green pigeon was only superficially similar to the Nicobar pigeon, and possibly distinct enough to warrant its own genus (related to ''Ptilinopus'', ''Ducula

''Ducula'' is a genus of the pigeon family Columbidae, collectively known as imperial pigeons. They are large to very large pigeons with a heavy build and medium to long tails. They are arboreal, feed mainly on fruit and are closely related to t ...

'', or '' Gymnophaps''). He also hypothesised that the bird might have inhabited a Pacific island, based on stories told by Tahitian islanders to the Tahitian scholar Teuira Henry in 1928 about a green and white speckled bird called ''titi''. The American palaeontologist David Steadman disputed the latter claim in a book review, noting that ''titi'' is an onomatopoeic

Onomatopoeia (or rarely echoism) is a type of word, or the process of creating a word, that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Common onomatopoeias in English include animal noises such as ''oink'', '' ...

word (resembling the sound of the bird) used especially for shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds in the petrel family Procellariidae. They have a global marine distribution, but are most common in temperate and cold waters, and are pelagic outside the breeding season.

Description

These tube ...

s (members of Procellariidae

The family (biology), family Procellariidae is a group of seabirds that comprises the fulmarine petrels, the gadfly petrels, the diving petrels, the prion (bird), prions, and the shearwaters. This family is part of the bird order (biology), orde ...

) in east Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

. The English ornithologists Julian P. Hume and Michael Walters, writing in 2012, agreed with Gibbs that the bird warranted generic status.

In 2020, after examining historical texts to clarify the origin and extinction date of the spotted green pigeon, the French ornithologist Philippe Raust pointed out that the information in Henry's 1928 book ''Ancient Tahiti'' was not gathered by her, but by her grandfather, the English reverend John Muggridge Orsmond, who collected ancient Tahitian traditions during the first half of the 19th century. The book devotes several pages to birds of Tahiti and its surroundings, including extinct ones, and the entry that Gibbs had linked to the spotted green pigeon reads: "The titi, which cried “titi”, now extinct in Tahiti, was speckled green and white and it was the shadow of the mountain gods". The ''titi'' was included in the paragraph relating to pigeons, which suggests it was well recognised as such, and Raust found it consistent with the spotted green pigeon. Though Steadman had dismissed the idea based on the name ''titi'' also being used for shearwaters, Raust pointed out that this name was used for a wider variety of birds with vocalisations that sound like "titi". Raust also noted that an 1851 Tahitian dictionary compiled by the Welsh reverend John Davies included the word ''tītīhope’ore'', which was used as a synonym for the ''titi'' of Henry in a 1999 dictionary. Based on definitions in Davies' dictionary, Raust translated this name as "tītī without (a long) tail." Raust suggested this name was used to distinguish it from the long-tailed koel (''Urodynamis taitensis''), which is called "tītī oroveo", and which is somewhat similar to Latham's illustration of the spotted green pigeon, being dark brown with paler spots and underparts. Raust believed that the study of these texts reinforced the Tahitian origin of the spotted green pigeon, and suggested this could be confirmed if possible bones of this species were one day found on Tahiti and analysed for DNA. So far, few paleontological sites on Tahiti have been studied, and fossils found there have not yet revealed unknown species.

The only specimen is today catalogued as NML-VZ D3538 at World Museum, Liverpool, where it is locked under environmentally-controlled conditions outside public view. It is kept in a cabinet in the museum's basement with other particularly important bird specimens, such as other extinct birds and type specimens. The store room is monitored for pests, and the temperature and humidity is kept stable to avoid infestations and damp. The specimen is handled with gloves when examined by researchers, and exposure to light is limited.

Evolution

In 2014, anancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient sources (typically Biological specimen, specimens, but also environmental DNA). Due to degradation processes (including Crosslinking of DNA, cross-linking, deamination and DNA fragmentation, fragme ...

analysis by the geneticist Tim H. Heupink and colleagues compared the gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s of the only spotted green pigeon specimen with that of other pigeons, based on samples extracted from two of its feathers. One of the resulting phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

trees (or cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

s) is shown below:

The spotted green pigeon was shown to be closest to the Nicobar pigeon. The

The spotted green pigeon was shown to be closest to the Nicobar pigeon. The genetic distance

Genetic distance is a measure of the genetics, genetic divergence between species or between population#Genetics, populations within a species, whether the distance measures time from common ancestor or degree of differentiation. Populations with ...

between the two was more than is seen within other pigeon species, but similar to the distance between different species within the same genus. This confirmed that the two were distinct species in the same genus, and that the spotted green pigeon was a unique, extinct taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

. The genus ''Caloenas'' was placed in a wider clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

in which most members showed a mixture of arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

(tree-dwelling) and terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth, as opposed to extraterrestrial.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on o ...

(ground-dwelling) traits. That ''Caloenas'' was placed in such a morphologically diverse clade may explain why many different relationships have previously been proposed for the members of the genus. A third species in the genus ''Caloenas'', the Kanaka pigeon (''C. canacorum''), is only known from subfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s discovered in New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

and Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

. This species was larger than the two other members of the genus, so it is unlikely that it represents the same species as the spotted green pigeon. The possibility that the spotted green pigeon was a hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two diff ...

between other species can also be disregarded based on the genetic results. The genetic findings were confirmed by a 2016 study by the geneticist André E. R. Soares and colleagues, which managed to assemble complete mitochondrial genomes

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the DNA contained in ...

from eleven pigeon species, including the spotted green pigeon.

The distribution of the Nicobar pigeon and the Kanaka pigeon (which does not appear to have had diminished flight abilities) suggests dispersal through island hopping

Leapfrogging was an amphibious military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Empire of Japan during World War II. The key idea was to bypass heavily fortified enemy islands instead of trying to capture every island i ...

and an origin for the spotted green pigeon in Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

or southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

. The fact that the closest relatives of ''Caloenas'' were the extinct subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

Raphinae

Columbidae is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with small heads, relatively short necks and slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. ...

(first demonstrated in a 2002 study), which consists of the dodo

The dodo (''Raphus cucullatus'') is an extinction, extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Mauritius, which is east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. The dodo's closest relative was the also-extinct and flightles ...

from Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

and the Rodrigues solitaire

The Rodrigues solitaire (''Pezophaps solitaria'') is an extinct flightless bird that was endemism, endemic to the island of Rodrigues, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Genetically within the family of Columbidae, pigeons and doves, it wa ...

from Rodrigues

Rodrigues ( ; Mauritian Creole, Creole: ) is a Autonomous administrative division, autonomous Outer islands of Mauritius, outer island of the Republic of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, about east of Mauritius. It is part of the Mascarene Isl ...

, indicates that the spotted green pigeon could also have originated somewhere in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. In any case, it seems most likely that the bird inhabited an island location, like its relatives. That the ''Caloenas'' pigeons were grouped in a clade at the base of the lineage leading to Raphinae indicates that the ancestors of the flightless

Flightless birds are birds that cannot fly, as they have, through evolution, lost the ability to. There are over 60 extant species, including the well-known ratites ( ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, and kiwis) and penguins. The smal ...

dodo and Rodrigues solitaire were able to fly, and reached the Mascarene Islands

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of Réunion. Their na ...

by island hopping from south Asia.

Description

Latham's 1823 description of the spotted green pigeon from ''A General History of Birds'' (expanded from the one in ''A General Synopsis of Birds'') reads as follows:

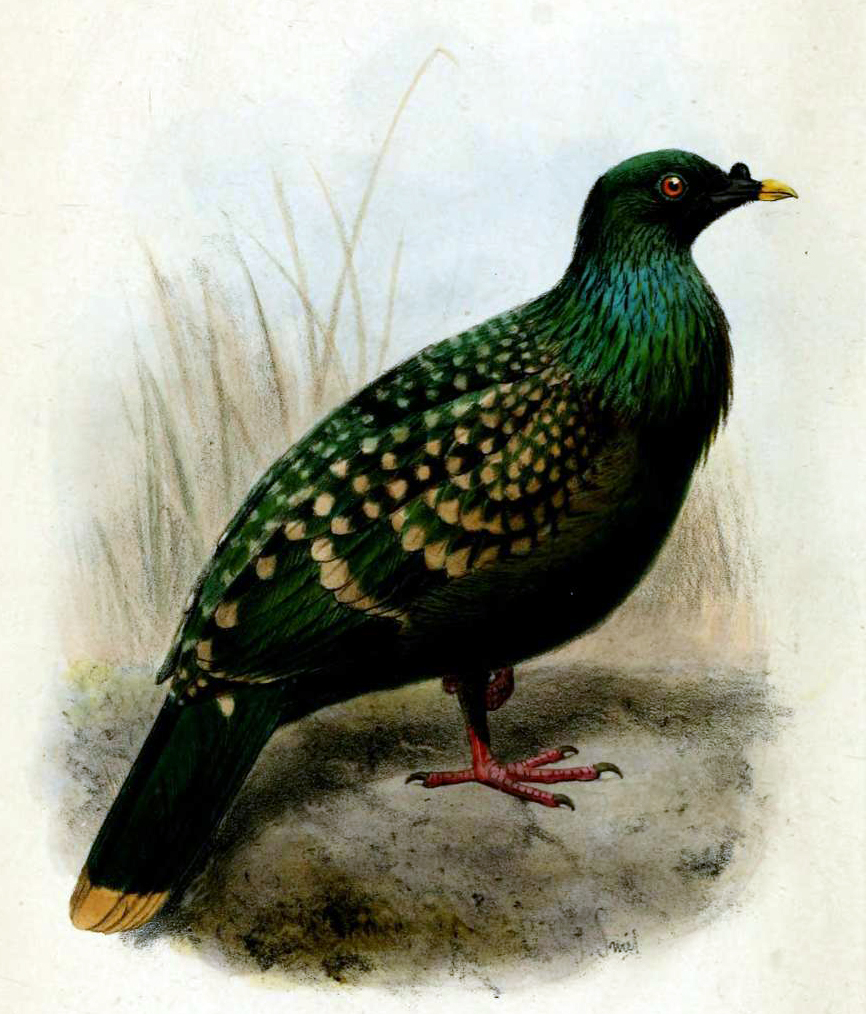

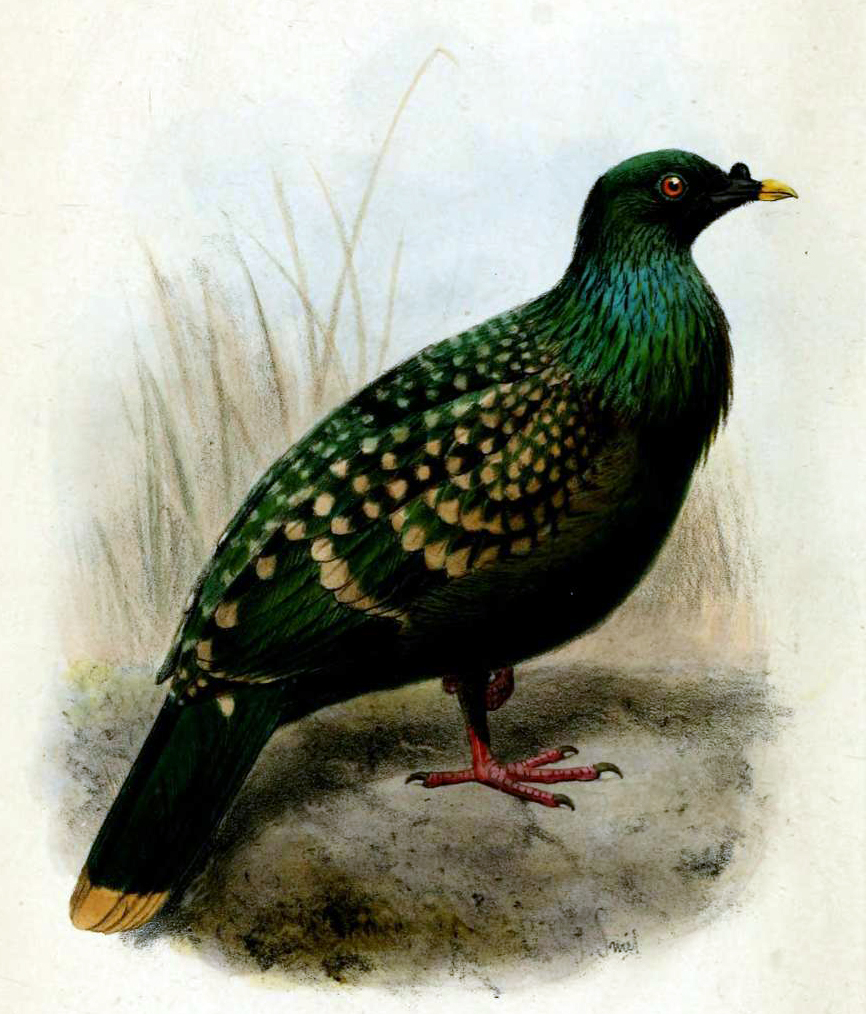

Most literature addressing the spotted green pigeon simply repeated Latham's descriptions, adding little new information, until Gibbs published a more detailed description in 2001, followed by the museum curator Hein van Grouw in 2014. The surviving specimen measures in length, though study specimens are often stretched or compressed during taxidermy, and may therefore not reflect the length of a living bird. The weight has not been recorded. The spotted green pigeon appears to have been smaller and slenderer than the Nicobar pigeon, which reaches , and the Kanaka pigeon appears to have been 25% larger than the latter. At in length, the tail is longer than that of the Nicobar pigeon, but the head is smaller in relation. The bill is , and the tarsus measures . Though the wings of the specimen appear to be short and rounded, and have been described as being long, vanGrouw discovered that the five outer

Latham's 1823 description of the spotted green pigeon from ''A General History of Birds'' (expanded from the one in ''A General Synopsis of Birds'') reads as follows:

Most literature addressing the spotted green pigeon simply repeated Latham's descriptions, adding little new information, until Gibbs published a more detailed description in 2001, followed by the museum curator Hein van Grouw in 2014. The surviving specimen measures in length, though study specimens are often stretched or compressed during taxidermy, and may therefore not reflect the length of a living bird. The weight has not been recorded. The spotted green pigeon appears to have been smaller and slenderer than the Nicobar pigeon, which reaches , and the Kanaka pigeon appears to have been 25% larger than the latter. At in length, the tail is longer than that of the Nicobar pigeon, but the head is smaller in relation. The bill is , and the tarsus measures . Though the wings of the specimen appear to be short and rounded, and have been described as being long, vanGrouw discovered that the five outer primary feathers

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

have been pulled out of each wing, and suggested that the wings would therefore had been about longer in life, around in total. This is in accordance with Latham's 1823 illustration, which shows a bird with longer wings.

The bill of the specimen is black with a yellowish tip, and the

The bill of the specimen is black with a yellowish tip, and the cere

The beak, bill, or Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for pecking, wikt:grasp#Verb, grasping, and holding (in wikt:probe ...

is also black, with feathers on the upper side, almost to the nostrils. The lores are naked, and the upper part of the head is sooty black. The rest of the head is mostly brownish-black. The feathers of the nape

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , ). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''nuchal rigidity'' ...

and the neck are slightly bifurcated and have a dark green gloss, the latter with coppery reflections. The feathers of the neck are elongated (sometimes referred to as hackles

Hackles are the erectile plumage or hair in the neck area of some birds and mammals.

In birds, the hackle is the group of feathers found along the back and side of the neck. The hackles of some types of chicken, particularly roosters, are long, ...

), and some of those on the sides and lower part have paler spots near the tips. Most of the feathers on the upperparts and wings are dark brown or brownish-black with a dark green gloss. Almost all of these feathers have a triangular, yellowish- buff spot at their tips. The spots are almost whitish on some of the scapular feathers

The following is a list of terms used in bird topography:

Plumage features

* Glossary_of_bird_terms#B, Back

* Abdomen#Vertabrates, Belly

* Breast

* Cheek

* Chin

* Crest (feathers), Crest

* Crown (anatomy), Crown

* Crown patch

* Ear-coverts

* ...

, vague and dark on the primary feathers. The underside of the wings is black with browner flight feathers, which have a pale spot or band at the tips. The breast is brownish-black with a faint green sheen. The tail is blackish with a dark green sheen, brownish-black on the underside, with a narrow, cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus ''Cinnamomum''. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, biscuits, b ...

-coloured band at the end. This differs from the rust-coloured tail-tip apparently shown in the drawing owned by Lever, and Latham's own illustration. The legs are small and slender, have long toes, large claws, and a comparatively short tarsus, whereas the Nicobar pigeon has shorter claws and a longer tarsus.

When examining the specimen, van Grouw noticed that the legs had at one point been detached and are now attached opposite their natural positions. The short feathering of the legs would therefore have been attached to the inner side of the upper tarsus in life, not the outer. The plate accompanying Forbes' 1898 article shows the feathers on the outer side, and depicts the legs as pinkish, whereas they are yellow in the skin. The spotted green pigeon has at times been described as having a knob at the base of its bill, similar to that of the Nicobar pigeon. This idea seems to have originated with Forbes, who had the bird depicted with this feature, perhaps due to his conviction that it was a species of ''Caloenas''; it was depicted with a knob as late as 2002. This is despite the fact that the surviving specimen does not possess a knob, and Latham did not mention or depict this feature, so such depictions are probably incorrect. The artificial eyes of the specimen were removed when it was prepared into a study skin, but red paint around the right eye-socket suggests that it was originally intended to have red eyes. It is unknown whether this represents the natural eye colour of the bird, yet the eyes were also depicted as red in Latham's illustration, which does not appear to have been based on the existing specimen. Forbes had the iris depicted as orange and the skin around the eye as green, though this was probably guesswork.

The triangular spots of the spotted green pigeon are not unique among pigeons, but are also seen in the spot-winged pigeon (''Columba maculosa'') and the

When examining the specimen, van Grouw noticed that the legs had at one point been detached and are now attached opposite their natural positions. The short feathering of the legs would therefore have been attached to the inner side of the upper tarsus in life, not the outer. The plate accompanying Forbes' 1898 article shows the feathers on the outer side, and depicts the legs as pinkish, whereas they are yellow in the skin. The spotted green pigeon has at times been described as having a knob at the base of its bill, similar to that of the Nicobar pigeon. This idea seems to have originated with Forbes, who had the bird depicted with this feature, perhaps due to his conviction that it was a species of ''Caloenas''; it was depicted with a knob as late as 2002. This is despite the fact that the surviving specimen does not possess a knob, and Latham did not mention or depict this feature, so such depictions are probably incorrect. The artificial eyes of the specimen were removed when it was prepared into a study skin, but red paint around the right eye-socket suggests that it was originally intended to have red eyes. It is unknown whether this represents the natural eye colour of the bird, yet the eyes were also depicted as red in Latham's illustration, which does not appear to have been based on the existing specimen. Forbes had the iris depicted as orange and the skin around the eye as green, though this was probably guesswork.

The triangular spots of the spotted green pigeon are not unique among pigeons, but are also seen in the spot-winged pigeon (''Columba maculosa'') and the speckled pigeon

The speckled pigeon (''Columba guinea''), also African rock pigeon or Guinea pigeon, is a pigeon that is a resident breeding bird in much of Africa south of the Sahara. It is a common and widespread species in open habitats over much of its range ...

(''C. guinea''), and are the result of lack of melanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

deposition during development. The yellow-buff coloured spots are very worn, while less worn feathers have white tips; this indicates that the former were stained during life or represent a different stage of plumage

Plumage () is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, there can b ...

, and that the latter were fresher. The plumage of the spotted green pigeon was distinct in being very soft compared to that of other pigeons, perhaps due to the body feathers being proportionally long. The hackles were not as elongated as those of the Nicobar pigeon, and the feathers did not differ from those of other pigeons in their microstructure

Microstructure is the very small scale structure of a material, defined as the structure of a prepared surface of material as revealed by an optical microscope above 25× magnification. The microstructure of a material (such as metals, polymer ...

. The plumage was also distinct in being very pigmented, except for the tips of the feathers, and even the down was dark, unlike that of most other birds (a feature otherwise seen in aberrant plumage).

Though the plumage of the spotted green pigeon resembles that of the Nicobar pigeon in some respects, it is also similar to that of species in the imperial pigeon genus ''Ducula''. The metallic-green colouration is commonly found among them, and similar hackles can be seen in the goliath imperial pigeon (''D. goliath''). The Polynesian imperial pigeon (''D. aurorae'') has similar soft feathers, and immature individuals of this species and the Pacific imperial pigeon

The Pacific imperial pigeon, Pacific pigeon, Pacific fruit pigeon or lupe (''Ducula pacifica'') is a widespread pigeon species in the family Columbidae. It is found in American Samoa, the Cook Islands, the smaller islands of eastern Fiji, Kiribat ...

(''D. pacifica'') have plumage different from that of juvenile and adult birds until they moult

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is a process by which an animal casts off parts of its body to serve some beneficial purpose, either at ...

. Therefore, vanGrouw found it possible that the dull, brownish-black underparts of the surviving spotted green pigeon specimen represents the plumage of an immature bird, as the adults of similar birds have stronger and more glossy iridescence

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear gradually to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Iridescence is caused by wave interference of light in microstru ...

. He suggested that the brighter bird with paler underparts and whiter wing tips seen in Latham's illustration may represent the adult plumage.

Behaviour and ecology

The behaviour of the spotted green pigeon was not recorded, but theories have been proposed based on its physical features. Gibbs found the delicate, part-feathered legs and long tail indicative of at least partially arboreal habits. After noting that the wings were not short after all, van Grouw stated that the bird would not have been terrestrial, unlike the related Nicobar pigeon. He pointed out that the overall proportions and shape of the bird (longer tail, shorter legs, primary feathers probably reaching the middle of the tail) was more similar to the pigeons of the genus ''Ducula''. It may therefore have been ecologically similar to those birds, have likewise been strongly arboreal, and kept to the dense

The behaviour of the spotted green pigeon was not recorded, but theories have been proposed based on its physical features. Gibbs found the delicate, part-feathered legs and long tail indicative of at least partially arboreal habits. After noting that the wings were not short after all, van Grouw stated that the bird would not have been terrestrial, unlike the related Nicobar pigeon. He pointed out that the overall proportions and shape of the bird (longer tail, shorter legs, primary feathers probably reaching the middle of the tail) was more similar to the pigeons of the genus ''Ducula''. It may therefore have been ecologically similar to those birds, have likewise been strongly arboreal, and kept to the dense canopy

Canopy may refer to:

Plants

* Canopy (biology), aboveground portion of plant community or crop (including forests)

* Canopy (grape), aboveground portion of grapes

Religion and ceremonies

* Baldachin or canopy of state, typically placed over an a ...

of forests. By contrast, the mainly terrestrial Nicobar pigeon forages on the forest floor

The forest floor, also called detritus or wikt:duff#Noun 2, duff, is the part of a forest ecosystem that mediates between the living, aboveground portion of the forest and the mineral soil, principally composed of dead and decaying plant matter ...

. The dark eyes of the Nicobar pigeon are typical of species that forage on forest floors, whereas the coloured bill and presumably coloured eyes of the spotted green pigeon are similar to those of frugivorous

A frugivore ( ) is an animal that thrives mostly on raw fruits or succulent fruit-like produce of plants such as roots, shoots, nuts and seeds. Approximately 20% of mammalian herbivores eat fruit. Frugivores are highly dependent on the abundance ...

(fruit-eating) pigeons. The feet of the spotted green pigeon are also similar to those of pigeons that forage in trees. The slender bill indicates that it fed on soft fruits.

Believing that the wings were short and round, Gibbs thought the bird was not a strong flyer, and therefore not nomadic (periodically moving from place to place). In spite of the evidently longer wings which might have made it a strong flyer, vanGrouw also thought it would have been a sedentary (mostly staying at the same location) bird, that preferred not to fly across open water, similar to species in ''Ducula''. It may have had a limited distribution on a small, remote island, which may explain why its provenance remains unknown. Raust pointed out that the fact that Polynesians considered the ''titi'' to emanate from mountain gods suggests that it lived in remote, high-altitude forests.

Extinction

The spotted green pigeon is most likely extinct, and may already have been close to extinction by the time Europeans arrived in its native area. The species may have disappeared due to being over-hunted and being preyed upon by introduced animals. Hume suggested that the bird may have survived until the 1820s. Raust agreed that the bird's extinction occurred during the 1820s, pointing out that the entry of the ''titi'' in Henry's 1928 book was based on much older accounts.References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q843120 Caloenas Extinct birds Bird extinctions since 1500 Birds described in 1789 Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin Collection of the World Museum Species known from a single specimen