The history of

California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

can be divided into the

Native American period (about 10,000 years ago until 1542), the

European exploration period (1542–1769), the

Spanish colonial period (1769–1821), the

Mexican period (1821–1848), and

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

statehood (September 9, 1850–present). California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in

pre-Columbian North America. After contact with

Spanish explorers, many of the

Native Americans died from foreign diseases. Finally, in the 19th century there was a genocide by United States government and private citizens, which is known as the

California genocide

The California genocide was a series of genocidal massacres of the indigenous peoples of California by United States soldiers and settlers during the 19th century. It began following the American conquest of California in the Mexican–Americ ...

.

After the

Portolá expedition

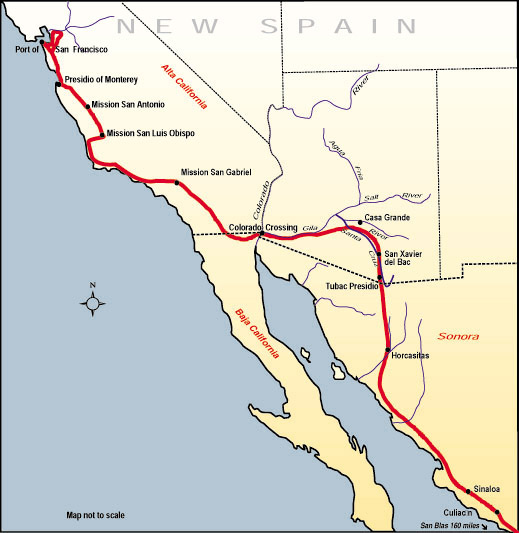

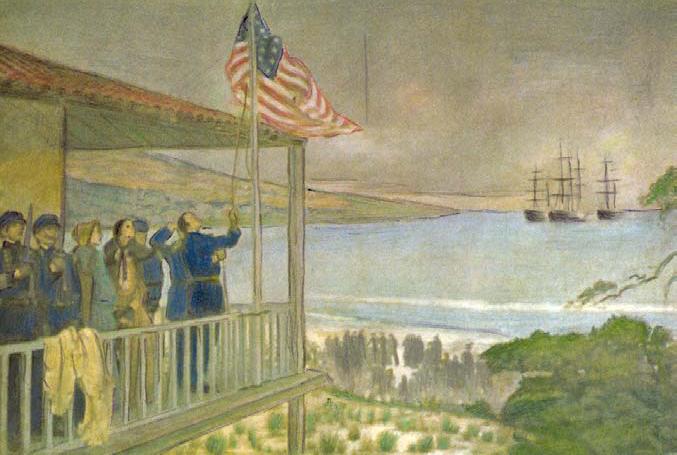

thumbnail, 250px, Point of San Francisco Bay Discovery

The Portolá expedition was a Spanish voyage of exploration in 1769–1770 that was the first recorded European exploration of the interior of the present-day California. It was led by Gas ...

of 1769–1770, Spanish missionaries began setting up 21

California missions

The Spanish missions in California () formed a series of 21 religious outposts or missions established between 1769 and 1833 in what is now the U.S. state of California. The missions were established by Catholic priests of the Franciscan ord ...

on or near the coast of

Alta (Upper) California, beginning with the

Mission San Diego de Alcala

Mission (from Latin 'the act of sending out'), Missions or The Mission may refer to:

Geography Australia

*Mission River (Queensland)

Canada

*Mission, British Columbia, a district municipality

*Mission, Calgary, Alberta, a neighbourhood

* O ...

near the location of the modern day city of San Diego, California. During the same period, Spanish military forces built several forts (''

presidio

A presidio (''jail, fortification'') was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire mainly between the 16th and 18th centuries in areas under their control or influence. The term is derived from the Latin word ''praesidium'' meaning ''pr ...

s'') and three small towns (''pueblos''). Two of the pueblos would eventually grow into the cities of

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

and

San Jose. After Mexico's Independence was won in 1821, California fell under the jurisdiction of the

First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire (, ) was a constitutional monarchy and the first independent government of Mexico. It was also the only former viceroyalty of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after gaining independence. The empire existed from 18 ...

. Fearing the influence of the Roman Catholic church over their newly independent nation, the Mexican government

"secularized" all of the missions. The missions were closed down in 1834; their priests mostly returned to Mexico. The churches ended religious services and fell into disrepair. The mission farmlands were seized by the government and handed out as grants to favorites. They left behind a "

Californio

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

" population of several thousand families, with a few small military garrisons. After losing the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

of 1846–1848, the Mexican Republic was forced to relinquish any claim to California to the United States.

The

California Gold Rush

The California gold rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the U ...

of 1848–1855 attracted hundreds of thousands of ambitious young people from around the world to Northern California. Only a few struck it rich, and many returned home disappointed. Most appreciated the other economic opportunities in California, especially in agriculture, and brought their families to join them. California became the 31st U.S. state in the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

and played a small role in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Chinese immigrants increasingly came under attack from

nativists; they were forced out of industry and agriculture and into

Chinatown

Chinatown ( zh, t=唐人街) is the catch-all name for an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, Asia, Africa, O ...

s in the larger cities. As gold petered out, California increasingly became a highly productive agricultural society. The coming of the railroads in 1869 linked its rich economy with the rest of the nation, and attracted a steady stream of settlers. In the late 19th century, Southern California, especially Los Angeles, started to grow rapidly.

History of California before 1900

Pre-contact period

Different tribes of

Native Americans lived in the area that is now California for an estimated 13,000 to 15,000 years. Archeological sites such as,

Borax Lake, the Cross Creek Site,

[Jones, T.L., R.T. Fitzgerald, D.J. Kennett, C. Micsicek, J. Fagan, J. Sharp, & J.M. Erlandson *2002 The Cross Creek Site (CA-SLO-1797) and its Implications for New World Colonization. American Antiquity 67:213–230.] Santa Barbara Channel Islands, Santa Barbara Coast's Sudden Flats, and the Scotts Valley site,

CA-SCR-177, offer evidence of human settlement in these areas from 13,000 -7,000 ybp. These people migrated into these areas supported by oceanic resources (an ecological zone referred to as the "Kelp Highway"), which extended from Asia to South America. The different kelps of the Pacific Rim are major contributors to the areas of productivity and biodiversity and support a wide variety of life such as marine mammals, shellfish, fish, seabirds and edible seaweeds. This biodiversity was a key condition that supported human migration and settlement during this early period.

Over 100 tribes and bands inhabited the area. Various estimates of the

Native American population in California during the pre-European period range from 100,000 to 300,000. California's population held about one-third of all Native Americans in the land now governed by the United States.

The native

horticulturalist

Horticulture (from ) is the art and science of growing fruits, vegetables, flowers, trees, shrubs and ornamental plants. Horticulture is commonly associated with the more professional and technical aspects of plant cultivation on a smaller and mo ...

s practiced various forms of

forest gardening and

fire-stick farming in the forests, grasslands, mixed woodlands, and wetlands, ensuring that desired food and medicine plants continued to be available. The

natives controlled fire on a localized basis to create a low-intensity

fire ecology

Fire ecology is a scientific discipline concerned with the effects of fire on natural ecosystems. Many ecosystems, particularly prairie, savanna, chaparral and coniferous forests, have evolved with fire as an essential contributor to habitat vit ...

to facilitate the growth of food and fiber materials and may have sustained a low-density agriculture in loose rotation; a sort of "wild"

permaculture

Permaculture is an approach to land management and settlement design that adopts arrangements observed in flourishing natural ecosystems. It includes a set of design principles derived using Systems theory, whole-systems thinking. It applies t ...

.

European exploration

''California'' was the name given to a mythical island populated only by beautiful

Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technology company

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek myth ...

warriors, as depicted in Greek myths, using gold tools and weapons in the popular early 16th-century romance novel ''

Las Sergas de Esplandián'' (The Adventures of Esplandián) by Spanish author

Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo

Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo (; – 1505) was a Castilian people, Castilian author who arranged the modern version of the chivalric romance ''Amadís de Gaula'', originally written in three books in the 14th century by an unknown author. Montalv ...

. This popular Spanish fantasy was printed in several editions with the earliest surviving edition published about 1510. In exploring

Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...

the earliest explorers thought the

Baja California Peninsula was an island and applied the name ''California'' to it. Mapmakers started using the name "California" to label the unexplored territory on the North American west coast.

European explorers from

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

explored the Pacific Coast of California beginning in the mid-16th century.

Francisco de Ulloa explored the west coast of present-day Mexico including the

Gulf of California

The Gulf of California (), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Vermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja California peninsula from ...

, proving that Baja California was a peninsula, but in spite of his discoveries the myth persisted in European circles that California was

an island.

Rumors of fabulously wealthy cities located somewhere along the California coast, as well as a possible

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, near the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Arctic Archipelago of Canada. The eastern route along the Arctic ...

that would provide a much shorter route to the

Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found i ...

, provided an incentive to explore further.

First European contact (1542)

The first Europeans to explore the

California coast were the members of a

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

sailing expedition led by captain

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (; 1497 – January 3, 1543) was a Portuguese maritime explorer best known for investigations of the west coast of North America, undertaken on behalf of the Spanish Empire. He was the first European to explore presen ...

from the Viceroyalty of

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(modern Mexico); they entered

San Diego Bay

San Diego Bay is a natural harbor and deepwater port in San Diego County, California, near the Mexico–United States border. The bay, which is long and wide, is the third largest of the three large, protected natural bays on California's of ...

on September 28, 1542, and reached at least as far north as

San Miguel Island. Cabrillo and his soldiers found that there was essentially nothing for the Spanish to easily exploit in California; located at the extreme limits of exploration and trade from Spain, it would be left essentially unexplored and unsettled for the next 234 years.

The Cabrillo expedition depicted the Indigenous populations as living at a subsistence level, typically located in small

rancherias of extended family groups of

100 to 150 people.

They had no apparent agriculture as understood by Europeans, no domesticated animals except dogs, no pottery; their tools were made out of wood, leather, woven baskets and netting, stone, and antler. Some shelters were made of branches and mud; some dwellings were built by digging into the ground two to three feet and then building a brush shelter on top covered with animal skins,

tules and/or mud.

The Cabrillo expedition did not see the far north of California, where on the coast and somewhat inland traditional architecture consists of rectangular redwood or cedar plank semisubterranean houses.

Opening of Spanish East Indies trading route (1565)

In 1565 the Spanish developed a trading route where they took gold and silver from the Americas and traded it for goods and spices from China and other Asian areas. The Spanish set up their main Asian base in

Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

in the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

and ruled it from Mexico City and Madrid. The trade with Mexico involved an annual passage of galleons. The Eastbound galleons first went north to about 40 degrees

latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and then turned east to use the westerly

trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, ...

s and currents. These galleons, after crossing most of the Pacific Ocean, would arrive off the California coast from 60 to over 120 days later somewhere near

Cape Mendocino

Cape Mendocino ( Spanish: ''Cabo Mendocino'', meaning "Cape of Mendoza"), which is located approximately north of San Francisco, is located on the Lost Coast entirely within Humboldt County, California, United States. At 124° 24' 34" W longit ...

, about north of San Francisco, at about 40° latitude. They could then sail south down the California coast, utilizing the available winds and the south-flowing

California Current

The California Current () is a cold water Pacific Ocean ocean current, current that moves southward along the western coast of North America, beginning off southern British Columbia and ending off southern Baja California Sur. It is considered an ...

, about . After sailing about south, they eventually reached their home port in Mexico.

The first modern Asians to set foot on what would be the United States occurred in 1587, when

Filipino slaves, prisoners, and crew arrived aboard these

Novohispanic

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

ships at

Morro Bay

Morro Bay (''Morro'', Spanish for "Hill") is a seaside city in San Luis Obispo County, California, United States. Located on the Central Coast of California, the city's population was 10,757 as of the 2020 census, up from 10,234 at the 2010 ...

on their way to central New Spain (Mexico). By chance, the

heirs of the Muslim Caliph Hasan ibn Ali in what was

once Islamic Manila, having embraced Christianity after the Spanish takeover, blended elements of Christianity with Islam. They passed through

California, which was named after a Caliph, en route to Guerrero, Mexico.

Subsequently, mixed Christian-Muslim families from the newly Hispanicized Philippines residing in the Americas took a stance against slavery, diverging from their Spanish counterparts who supported it. Unlike their

Crypto-Muslim and

Crypto-Jewish compatriots from Spain who supported the illegal slave trade, the mixed Muslim-Christian Filipinos in the Americas stood in solidarity with

Native American and African efforts against slavery.

Francis Drake's claim (1579)

After successfully sacking Spanish towns and plundering Spanish ships along their Pacific coast colonies in the Americas, English explorer and circumnavigator

Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

landed in

Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, before exploring and claiming an undefined portion of the California coast in 1579. This is believed to have taken place north of the future city of

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, perhaps around

Point Reyes

Point Reyes ( , meaning 'Cape of the Kings') is a prominent landform and popular tourist destination on the Pacific coast of Marin County in Northern California. It is approximately west-northwest of San Francisco. The term is often applied ...

or the nearby Drake's Cove. Drake established friendly relations with the

Coast Miwok and claimed the area for the

English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself king of the Anglo-Sax ...

as ''Nova Albion'', or

New Albion

New Albion, also known as ''Nova Albion'' (in reference to Albion, an archaic name for Great Britain), was the name of the continental area north of Mexico claimed by Sir Francis Drake for Kingdom of England, England when he landed on the Nort ...

.

Sebastián Vizcaíno's exploration

In 1602, the Spaniard

Sebastián Vizcaíno

Sebastián Vizcaíno (c. 1548–1624) was a Spanish soldier, entrepreneur, explorer, and diplomat whose varied roles took him to New Spain, the Baja California peninsula, the California coast and Asia.

Early career

Vizcaíno was born in ...

explored California's coastline on behalf of

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

from San Diego. He named

San Diego Bay

San Diego Bay is a natural harbor and deepwater port in San Diego County, California, near the Mexico–United States border. The bay, which is long and wide, is the third largest of the three large, protected natural bays on California's of ...

, also putting ashore in

Monterey, California

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, California, Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a popu ...

, and made glowing reports of the Monterey bay area as a possible anchorage for ships with land suitable for growing crops. He also provided rudimentary charts of the coastal waters, which were used for nearly 200 years.

Spanish colonial period (1769–1821)

The Spanish divided California into two parts, Baja California and

Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

, as provinces of New Spain (Mexico). Baja or lower California consisted of the Baja Peninsula and terminated roughly at

San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

, where Alta California started. The eastern and northern boundaries of Alta California were very indefinite, as the Spanish, despite a lack of physical presence and settlements, claimed essentially everything in what is now the western United States.

The first permanent

mission in Baja California,

Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó, was founded on October 15, 1697, by

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest

Juan Maria Salvatierra (1648–1717) accompanied by one small boat's crew and six soldiers. After the establishment of Missions in Alta California after 1769, the Spanish treated Baja California and Alta California, known as Las Californias, as a single administrative unit with Monterey as its capital, and falling under the jurisdiction of the Viceroyalty of New Spain based in Mexico City.

Nearly all the missions in Baja California were established by members of the

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

order supported by a few soldiers. After a power dispute between

Charles III of Spain

Charles III (; 20 January 1716 – 14 December 1788) was King of Spain in the years 1759 to 1788. He was also Duke of Parma and Piacenza, as Charles I (1731–1735); King of Naples, as Charles VII; and King of Sicily, as Charles III (or V) (1735� ...

and the Jesuits, the Jesuit colleges were closed and the

Jesuits were expelled from Mexico and South America in 1767 and deported back to Spain. After the forcible expulsion of the Jesuit order, most of the missions were taken over by

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

and later

Dominican friars. Both of these groups were under much more direct control of the

Spanish monarchy

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish monarchy is constitu ...

. This reorganization left many missions abandoned in Sonora Mexico and Baja California.

Concerns about the intrusions of British and

Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

merchants into Spain's colonies in California prompted the extension of

Franciscan missions to Alta California, as well as

presidio

A presidio (''jail, fortification'') was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire mainly between the 16th and 18th centuries in areas under their control or influence. The term is derived from the Latin word ''praesidium'' meaning ''pr ...

s.

One of Spain's gains from the Seven Years' War was the French

Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of t ...

which was given to Spain in the

1763 Treaty of Paris. Another potential colonial power already established in the Pacific was Russia, whose

maritime fur trade of mostly sea otter and fur seals was pressing down from Alaska to the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

's lower reaches. These furs could be traded in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

for large profits.

The Spanish settlement of Alta California was the last colonization project to expand Spain's vastly over-extended empire in North America, and they tried to do it with minimal cost and support. Approximately half the cost of settling Alta California was borne by donations and half by funds from the Spanish crown.

Massive Indian revolts in

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

's

Pueblo Revolt

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, also known as Popé, Popé's Rebellion or Po'pay's Rebellion, was an uprising of most of the Indigenous Pueblo people against the Spanish Empire, Spanish colonizers in the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, larger t ...

among the

Pueblo Indians

The Pueblo peoples are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Among the currently inhabited Pueblos, Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi are some of the ...

of the

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

valley in the 1680s as well as

Pima Indian Revolt in 1751 and the ongoing

Seri conflicts in

Sonora Mexico provided the Franciscan friars with arguments to establish missions with fewer colonial settlers. In particular, the sexual exploitation of Native American women by Spanish soldiers sparked violent reprisals from the Native community and the spread of venereal disease.

The remoteness and isolation of California, the lack of large organized tribes, the lack of agricultural traditions, the absence of any domesticated animals larger than a dog, and a food supply consisting primarily of acorns (unpalatable to most Europeans) meant the missions in California would be very difficult to establish and sustain and made the area unattractive to most potential colonists. A few soldiers and friars financed by the Church and State would form the backbone of the proposed settlement of California.

Portolá expedition (1769–1770)

In 1769, the Spanish Visitor General,

José de Gálvez

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced very differently in each of the two languages: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced ...

, planned a

five part expedition, consisting of three units by sea and two by land, to start settling Alta California.

Gaspar de Portolà

Gaspar is a given and/or surname of French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish origin, cognate to Casper (given name) or Casper (surname).

It is a name of christian origin, per Saint Gaspar, one of the three wise men mentioned in the Armenian ...

volunteered to command the expedition. The Catholic Church was represented by Franciscan friar

Junípero Serra

Saint Junípero Serra Ferrer (; ; November 24, 1713August 28, 1784), popularly known simply as Junipero Serra, was a Spanish Roman Catholic, Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Order. He is credited with establishing the Francis ...

and his fellow friars. All five detachments of soldiers, friars and future colonists were to meet on the shores of San Diego Bay. The first ship, the ''San Carlos'', sailed from

La Paz

La Paz, officially Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Aymara language, Aymara: Chuqi Yapu ), is the seat of government of the Bolivia, Plurinational State of Bolivia. With 755,732 residents as of 2024, La Paz is the List of Bolivian cities by populati ...

on January 10, 1769, and the ''San Antonio'' sailed on February 15. The ''San Antonio'' arrived in San Diego Bay on April 11 and the ''San Carlos'' on April 29. The third vessel, the ''San José'', left New Spain later that spring but was lost at sea with no survivors.

The first land party, led by

Fernando Rivera y Moncada

Fernando Javier Rivera y Moncada (c. 1725 – July 18, 1781) was a soldier of the Spanish Empire who served in The Californias (''Las Californias''), the far northwest frontier of New Spain. He participated in several early overland exploration ...

, left from the Franciscan

Misión San Fernando Velicatá on March 24, 1769. With Rivera was

Juan Crespí

Juan Crespí, OFM (Catalan language, Catalan: ''Joan Crespí''; 1 March 1721 – 1 January 1782) was a Franciscan missionary and explorer of The Californias, Las Californias.

Biography

A native of Majorca, Crespí entered the Franciscan ord ...

, famed diarist of the entire expedition. That group arrived in San Diego on May 4. A later expedition led by Portolà, which included Junípero Serra, the President of the Missions, along with a combination of missionaries, settlers, and leather-jacket soldiers including

José Raimundo Carrillo, left Velicata on May 15, 1769, and arrived in San Diego on June 29.

They took with them about 46 mules, 200 cows and 140 horses—all that could be spared by the poor Baja Missions.

Fernando de Rivera was appointed to command the lead party that would scout out a land route and blaze a trail to San Diego.

Food was short, and the Indians accompanying them were expected to forage for most of what they needed. Many Indian neophytes died along the way; even more deserted. The two groups traveling from Lower California on foot had to cross about of the very dry and rugged

Baja Peninsula.

The part of the expedition that took place over land took about 40–51 days to get to San Diego. The contingent coming by sea encountered the south flowing

California Current

The California Current () is a cold water Pacific Ocean ocean current, current that moves southward along the western coast of North America, beginning off southern British Columbia and ending off southern Baja California Sur. It is considered an ...

and strong head winds, and were still straggling in three months after they set sail. After their arduous journeys, most people aboard the ships were ill, chiefly from

scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, and many had died. Out of a total of about 219 who had left Baja California, little more than 100 survived. The survivors established the

Presidio of San Diego on May 14, 1769.

Mission San Diego de Alcala

Mission (from Latin 'the act of sending out'), Missions or The Mission may refer to:

Geography Australia

*Mission River (Queensland)

Canada

*Mission, British Columbia, a district municipality

*Mission, Calgary, Alberta, a neighbourhood

* O ...

was established on July 16, 1769. As the first of the presidios and Spanish missions in California, they provided the base of operations for the Spanish colonization of Alta California (the present-day US state of California).

On July 14, 1769, an expedition was dispatched from San Diego to find the port of Monterey. Not recognizing the

Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by about 75 miles (120 km), accessible via California S ...

from the description written by

Sebastián Vizcaíno

Sebastián Vizcaíno (c. 1548–1624) was a Spanish soldier, entrepreneur, explorer, and diplomat whose varied roles took him to New Spain, the Baja California peninsula, the California coast and Asia.

Early career

Vizcaíno was born in ...

almost 200 years prior, the expedition traveled beyond it to what is now the

San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

area. The exploration party, led by Don

Gaspar de Portolà

Gaspar is a given and/or surname of French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish origin, cognate to Casper (given name) or Casper (surname).

It is a name of christian origin, per Saint Gaspar, one of the three wise men mentioned in the Armenian ...

, arrived on November 2, 1769, at

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

.

One of the greatest natural harbors on the west coast of America had finally been discovered by land. The expedition returned to San Diego on January 24, 1770. The Presidio and Mission of

San Carlos de Borromeo de Monterey were established on June 3, 1770, by Portola, Serra, and Crespi, with Monterey becoming the capital of the California province in 1777.

Food shortages

Without any agricultural crops or experience gathering, preparing and eating the ground acorns and grass seeds the Indians subsisted on for much of the year, the shortage of food at San Diego became extremely critical during the first few months of 1770. They subsisted by eating some of their cattle, wild geese, fish, and other food exchanged with the Indians for clothing, but the ravages of scurvy continued because there was then no understanding of the cause or cure of scurvy (a deficiency of vitamin C in fresh food). A small quantity of corn they had planted grew well, only to be eaten by birds. Portolá sent Captain Rivera and a small detachment of about 40 soldiers south to the Baja California missions in February to obtain more cattle and a pack-train of supplies.

Fewer mouths to feed temporarily eased the drain on San Diego's scant provisions, but within weeks, acute hunger and increased sickness (scurvy) again threatened to force abandonment of the San Diego "Mission". Portolá finally decided that if no relief ship arrived by March 19, 1770, they would leave to return to the

Novohispanic

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

missions on the

Baja Peninsula the next morning "because there were not enough provisions to wait longer and the men had not come to perish from hunger". At three o'clock in the afternoon on March 19, 1770, as if by a miracle, the sails of the

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on Mast (sailing), masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing Square rig, square-rigged or Fore-an ...

''San Antonio'', loaded with relief supplies, were discernible on the horizon. The Spanish settlement of Alta California would continue.

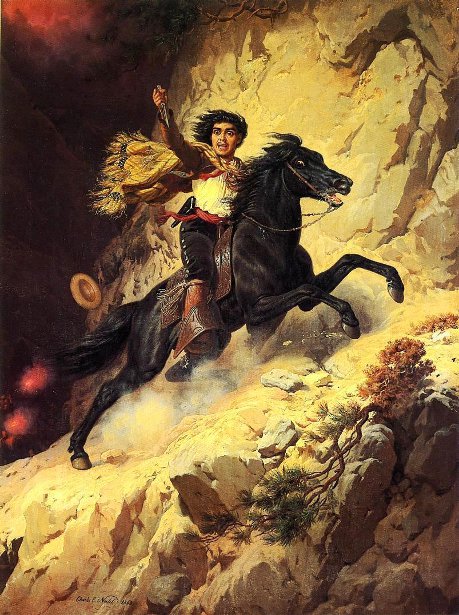

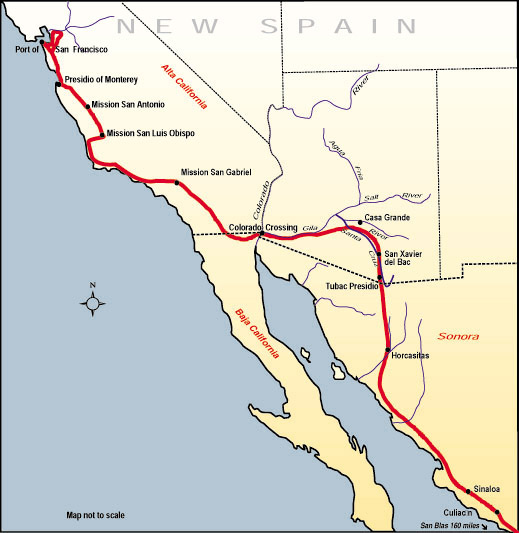

Anza Expeditions (1774–1776)

Juan Bautista de Anza

Juan Bautista de Anza Bezerra Nieto (July 6 or 7, 1736 – December 19, 1788) was a Novohispanic/Mexican expeditionary leader, military officer, and politician primarily in California and New Mexico under the Spanish Empire. He is credited as on ...

, leading an exploratory expedition on January 8, 1774, with 3

chaplains

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a ho ...

, 20 soldiers, 11 servants, 35 mules, 65 cattle, and 140 horses set forth from

Tubac

Tubac is a census-designated place (CDP) in Santa Cruz County, Arizona, United States. The population was 1,191 at the 2010 census. The place name "Tubac" is an English borrowing from a Hispanicized form of the O'odham name ''Cuwak'', which ...

south of present-day

Tucson, Arizona

Tucson (; ; ) is a city in Pima County, Arizona, United States, and its county seat. It is the second-most populous city in Arizona, behind Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix, with a population of 542,630 in the 2020 United States census. The Tucson ...

. They went across the Sonoran desert to California from Mexico by swinging south of the

Gila River

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of ...

to avoid

Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

attacks until they hit the

Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

at the

Yuma Crossing

Yuma Crossing is a site in Arizona and California that is significant for its association with transportation and communication across the Colorado River. It connected New Spain and Las Californias in the Spanish Colonial period in and also duri ...

—about the only way across the Colorado River. The friendly

Quechan

The Quechan ( Quechan: ''Kwatsáan'' 'those who descended'), or Yuma, are a Native American tribe who live on the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation on the lower Colorado River in Arizona and California just north of the Mexican border. Despite ...

(Yuma) Indians (2,000–3,000) he encountered there were growing most of their food, using irrigation systems, and had already imported pottery, horses, wheat and a few other crops from

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

.

After crossing the Colorado to avoid the impassable

Algodones Dunes

The Algodones Dunes is a large sand dune field, or Erg (landform), erg, located in the southeastern portion of the U.S. state of California, near the border with Arizona and the Mexican state of Baja California. The field is approximately long ...

west of

Yuma, Arizona

Yuma is a city in and the county seat of Yuma County, Arizona, United States. The city's population was 95,548 at the 2020 census, up from the 2010 census population of 93,064.

Yuma is the principal city of the Yuma, Arizona, Metropolitan ...

, they followed the river about south (to about the Arizona's southwest corner on the Colorado River) before turning northwest to about today's

Mexicali, Mexico

Mexicali (; ) is the capital city of the Mexican state of Baja California. The city, which is the seat of the Mexicali Municipality, has a population of 689,775, according to the 2010 census, while the Calexico–Mexicali metropolitan area i ...

and then turning north through today's

Imperial Valley

The Imperial Valley ( or ''Valle Imperial'') of Southern California lies in Imperial and Riverside counties, with an urban area centered on the city of El Centro. The Valley is bordered by the Colorado River to the east and, in part, the S ...

and then northwest again before reaching

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel () is a Californian mission and historic landmark in San Gabriel, California. It was founded by the Spanish Empire on the Nativity of Mary September 8, 1771, as the fourth of what would become twenty-one Spanish mi ...

near the future city of

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

. It took Anza about 74 days to do this initial reconnaissance trip to establish a land route into California. On his return trip he went down the

Gila River

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of ...

until hitting the

Santa Cruz River and continuing on to Tubac. The return trip only took 23 days, and he encountered several peaceful and populous agricultural tribes with irrigation systems located along the Gila River.

In Anza's second trip (1775–1776) he returned to California with 240 friars, soldiers and colonists with their families. They took 695 horses and mules and 385

Texas Longhorn

The Texas Longhorn is an American breed of beef cattle, characterized by its long horns, which can span more than from tip to tip. It derives from cattle brought from the Iberian Peninsula to the Americas by Spanish conquistadors from the ti ...

cattle with them. The approximately 200 surviving cattle and an unknown number of horses (many of each were lost or eaten along the way) started the cattle and horse raising industry in California. In California the cattle and horses had few predators and plentiful grass in all but drought years. They essentially grew and multiplied as feral animals, doubling roughly every two years.

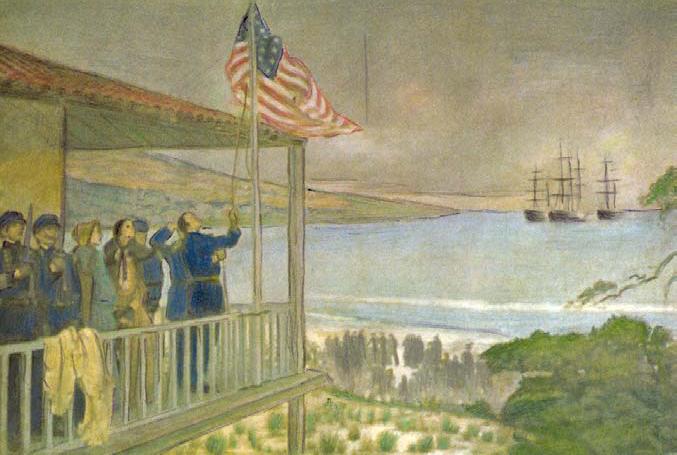

The expedition started from Tubac, Arizona, on October 22, 1775, and arrived at

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

on March 28, 1776. There they selected the sites for the

Presidio of San Francisco

The Presidio of San Francisco (originally, El Presidio Real de San Francisco or The Royal Fortress of Saint Francis) is a park and former U.S. Army post on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, and is part ...

, followed by a

mission,

Mission San Francisco de Asís

The Mission San Francisco de Asís (), also known as Mission Dolores, is a historic Catholic Church, Catholic church complex in San Francisco, San Francisco, California. Operated by the Archdiocese of San Francisco, the complex was founded in ...

(Mission Dolores), within the future city of

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, which took its name from the mission.

In 1776, the

Domínguez–Escalante expedition concurrently was launched by Franciscan missionaries to find an overland route between New Mexico and California. However, after reaching as west as modern-day Arizona by 1777, the missionaries could no longer continue and decided to return to Santa Fe.

Further expeditions

In 1780, the Spanish established two combination missions and pueblos at the Yuma Crossing:

Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer and

Mission Puerto de Purísima Concepción

Mission Puerto de Purísima Concepción was founded near what is now Yuma, Arizona, United States, on the California side of the Colorado River, in October 1780, by the Franciscan missionary Francisco Garcés. The settlement was not part of the C ...

. Both these pueblos and missions were on the California side of the Colorado River but were administered by the Arizona authorities. On July 17–18, 1781, the Yuma (

Quechan

The Quechan ( Quechan: ''Kwatsáan'' 'those who descended'), or Yuma, are a Native American tribe who live on the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation on the lower Colorado River in Arizona and California just north of the Mexican border. Despite ...

) Indians, in a dispute with the Spanish,

destroyed both missions and pueblos—killing 103 soldiers, colonists, and Friars and capturing about 80 prisoners, mostly women and children. In four well-supported punitive expeditions in 1782 and 1783 against the Quechans, the Spanish managed to gather their dead and ransom nearly all the prisoners, but failed to re-open the Anza Trail.

The

Yuma Crossing

Yuma Crossing is a site in Arizona and California that is significant for its association with transportation and communication across the Colorado River. It connected New Spain and Las Californias in the Spanish Colonial period in and also duri ...

was closed for Spanish traffic and it would stay closed until about 1846. California was nearly isolated again from land based travel. About the only way into California from Mexico would now be a 40 to 60-day voyage by sea. The average of 2.5 ships per year from 1769 to 1824 meant that additional colonists coming to Alta California were few and far between.

Eventually, 21

California Missions

The Spanish missions in California () formed a series of 21 religious outposts or missions established between 1769 and 1833 in what is now the U.S. state of California. The missions were established by Catholic priests of the Franciscan ord ...

were established along the California coast from San Diego to San Francisco—about up the coast. The missions were nearly all located within of the coast and almost no exploration or settlements were made in the

Central Valley or the

Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada ( ) is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primari ...

. The only expeditions anywhere close to the Central Valley and Sierras were the rare forays by soldiers undertaken to recover runaway Indians who had escaped from the Missions. The "settled" territory of about was about 10% of California's eventual territory.

In 1786,

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse

Jean-François () is a French given name. Notable people bearing the given name include:

* Jean-François Carenco (born 1952), French politician

* Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832), French Egyptologist

* Jean-François Clervoy (born 1958) ...

led a group of scientists and artists who compiled an account of the Californian mission system, the land, and the people. Traders, whalers, and scientific missions followed in the next decades.

California Mission system

The

California Missions

The Spanish missions in California () formed a series of 21 religious outposts or missions established between 1769 and 1833 in what is now the U.S. state of California. The missions were established by Catholic priests of the Franciscan ord ...

, after they were all established, were located about one day's horseback ride apart for easier communication and linked by the

El Camino Real trail. These Missions were typically manned by two to three friars and three to ten soldiers. Virtually all the physical work was done by indigenous people convinced to or coerced into joining the missions. The padres provided instructions for making adobe bricks, building mission buildings, planting fields, digging irrigation ditches, growing new grains and vegetables, herding cattle and horses, singing, speaking Spanish, and understanding the

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

faith—all that was thought to be necessary to bring the Indians to be able to support themselves and their new church.

The soldiers supervised the construction of the presidios (forts) and were responsible for keeping order and preventing and/or capturing runaway Indians that tried to leave the missions. Nearly all of the Indians adjoining the missions were induced to join the various missions built in California. Once the Indians had joined the mission, if they tried to leave, soldiers were sent out to retrieve them. In the 1830s,

Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast'' a ...

observed that Indians were regarded and treated as slaves by

Californio

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

s.

The missions eventually claimed about of the available land in California or roughly of land per mission. The rest of the land was considered the property of the

Spanish monarchy

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish monarchy is constitu ...

. To encourage settlement of the territory, large land grants were given to retired soldiers and colonists. Most grants were virtually free and typically went to friends and relatives in the California government. A few foreign colonists were accepted if they accepted Spanish citizenship and joined the Catholic Faith. The

Mexican Inquisition

The Mexican Inquisition was an extension of the Spanish Inquisition into New Spain. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was not only a political event for the Spanish, but a religious event as well. In the early 16th century, the Protesta ...

was still in nearly full force and forbade Protestants living in Mexican controlled territory. In the Spanish colonial period many of these grants were later turned into

Ranchos.

Spain made about 30 of these large grants, nearly all several square leagues (1 Spanish league = ) each in size. The total land granted to settlers in the Spanish colonial era was about or about each. The few owners of these large ranchos patterned themselves after the landed gentry in Spain and were devoted to keeping themselves living in a grand style. The rest of the population they expected to support them. Their mostly unpaid workers were nearly all Spanish trained Indians or

peons that had learned how to ride horses and raise some crops. The majority of the ranch hands were paid with room and board, rough clothing, rough housing, and no salary.

The main products of these ranchos were cattle, horses and sheep, most of which lived virtually wild. The cattle were mostly killed for fresh meat, as well as hides and tallow (fat) which could be traded or sold for money or goods. As the

cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

herds increased there came a time when nearly everything that could be made of leather was—doors, window coverings, stools,

chaps

Chaparreras or chaps () are a type of sturdy over-pants (overalls) or leggings of Mexican origin, made of leather, without a seat, made up of two separate legs that are fastened to the waist with straps or belt. They are worn over trousers and ...

, leggings, vests lariats (

riatas),

saddle

A saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals.

It is not know ...

s, boots, etc. Since there was no refrigeration then, often a cow was killed for the day's fresh meat and the hide and tallow salvaged for sale later. After taking the cattle's hide and tallow their carcasses were left to rot or feed the California

grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horr ...

s which roamed wild in California at that time, or to feed the packs of dogs that typically lived at each rancho.

A series of four ''presidios'', or Royal Forts, each manned by 10 to 100 men, were built in Alta California by the Spanish crown through New Spain. California installations were established in

San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

(

El Presidio Real de San Diego) founded in 1769, in San Francisco (

El Presidio Real de San Francisco) founded in 1776, and in

Santa Barbara (

El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara) founded in 1782. After the Spanish colonial era the

Presidio of Sonoma in

Sonoma, California was founded in 1834.

To support the presidios and the missions, half a dozen towns (called pueblos) were established in California. The pueblos of

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

,

San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

,

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

,

Santa Barbara,

Monterey

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a population of 30,218 in the 2020 census.

The city was fou ...

,

Villa de Branciforte (later abandoned before later becoming

Santa Cruz), and the pueblo of

San Jose, were all established to support the

Missions and presidios in California. These were the only towns (pueblos) in California.

In 1804, the

Province of Las Californias was divided into two territorial administrations following the precedent of

Francisco Palóu

Francisco Palóu (, ; 1723–1789) was a Spanish Franciscan missionary, administrator, and historian on the Baja California Peninsula and in Alta California. Palóu made significant contributions to the Alta California and Baja California miss ...

's division between the Dominican missions of Baja California and Franciscan missions of Alta California, governing all Californian lands North of

Misión San Miguel Arcángel de la Frontera (including the

Tijuana River Valley and modern-day

Mexicali

Mexicali (; ) is the capital city of the States of Mexico, Mexican state of Baja California. The city, which is the seat of the Mexicali Municipality, has a population of 689,775, according to the 2010 census, while the Calexico–Mexicali, Cale ...

) with

Monterey

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a population of 30,218 in the 2020 census.

The city was fou ...

as the capital of the new territory.

Mexican period (1821 to 1848)

In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain, first as the

First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire (, ) was a constitutional monarchy and the first independent government of Mexico. It was also the only former viceroyalty of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after gaining independence. The empire existed from 18 ...

, then as the Mexican Republic. Alta California became a territory rather than a full state. The territorial capital remained in

Monterey, California

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, California, Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a popu ...

, with a governor as executive official.

Mexico, after independence, was unstable with about

40 changes of government, in the 27 years prior to 1848—an average government duration was 7.9 months. In Alta California, Mexico inherited a large, sparsely settled, poor, backwater province paying little or no net tax revenue to the Mexican state. In addition, Alta California had a declining Mission system as the

Mission Indian population in Alta California continued to rapidly decrease.

The number of Alta California settlers, always a minority of total population, slowly increased mostly by more births than deaths in the Californio population in California. After the closure of the

de Anza Trail across the

Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

in 1781 immigration from Mexico was nearly all by ship. California continued to be a sparsely populated and isolated territory.

Trade policy

Even before Mexico gained control of

Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

the onerous Spanish rules against trading with foreigners began to break down as the declining Spanish fleet could not enforce their no-trading policies. The settlers, and their descendants (who became known as

Californio

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

s), were eager to trade for new commodities, finished goods, luxury goods, and other merchandise. The Mexican government abolished the no trade with foreign ships policy and soon regular trading trips were being made.

In addition, a number of Europeans and Americans became naturalized Mexican citizens and settled in early California. Some of those became rancheros and traders during the Mexican period, such as

Abel Stearns.

Cattle hides and tallow, along with

marine mammal fur and other goods, provided the necessary trade articles for mutually beneficial trade. The first American, English, and Russian

trading ships first appeared in California a few years before 1820. The classic book ''

Two Years Before the Mast

''Two Years Before the Mast'' is a memoir by the American author Richard Henry Dana Jr., published in 1840, having been written after a two-year sea voyage from Boston to California on a merchant ship starting in 1834. A Two Years Before the Mast ...

'' by

Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast'' a ...

provides a good first hand account of this trade. From 1825 to 1848 the average number of ships traveling to California increased to about 25 ships per year—a large increase from the average of 2.5 ships per year from 1769 to 1824.

The main

port of entry

In general, a port of entry (POE) is a place where one may lawfully enter a country. It typically has border control, border security staff and facilities to check passports and visas and to inspect luggage to assure that contraband is not impo ...

for trading purposes was Monterey, where custom duties of up to 100% (also called

tariffs

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials and is ...

) were applied. These high duties gave rise to much bribery and smuggling, as avoiding the tariffs made more money for the ship owners and made the goods less costly to the customers. Essentially all the cost of the California government (what little there was) was paid for by these tariffs. In this they were much like the United States in 1850, where about 89% of the revenue of its federal government came from import tariffs, although at an average rate of about 20%.

Secularization of the mission system

So many mission Indians died from exposure to harsh conditions and diseases like measles, diphtheria, smallpox, syphilis, etc. that at times raids were undertaken to new villages in the interior to supplement the supply of Indian women. This increase in deaths was accompanied by a very low live birth rate among the surviving Indian population. As reported by Krell, as of December 31, 1832, the mission

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

chaplains had performed a combined total of 87,787 baptisms and 24,529 marriages, and recorded 63,789 deaths.

If Krell's numbers are to be believed (others have very different numbers) the Mission Indian population had declined from a peak of about 87,000 in about 1800 to about 14,000 in 1832 and continued to decline. The Missions were becoming ever more strained as the number of Indian converts drastically declined and the deaths greatly exceeded the births. The ratio of Indian births to deaths is believed to have been less than 0.5 Indian births per death.

The missions, as originally envisioned, were to last only about ten years before being converted to regular parishes. When the California missions were abolished in 1834, some

missions had existed over 66 years, but the Mission Indians were still not self-sufficient, proficient in Spanish, or wholly Catholic. Indigenous resistance and uprisings against violent settler colonialism was widespread across the missions despite severe and continuing decline in the native Californian population.

In 1834 Mexico, in response to demands that the Catholic Church give up much of the Mission property, started the process of

secularizing the

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

-run missions.

Mission San Juan Capistrano

Mission San Juan Capistrano () is a Spanish missions in California, Spanish mission in San Juan Capistrano, California, San Juan Capistrano, Orange County, California, Orange County, California. Founded November 1, 1776 in colonial ''The Califo ...

was the very first to feel the effects of this legislation the following year when, on August 9, 1834, Governor Figueroa issued his "Decree of Confiscation".

Nine other missions quickly followed, with six more in 1835;

San Buenaventura and San Francisco de Asís were among the last to succumb, in June and December 1836, respectively. The

Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

s soon thereafter abandoned most of the missions, taking with them almost everything of value they could, after which the locals typically plundered the mission buildings for construction materials, furniture, etc. or the mission buildings were sold off to serve other uses.

In spite of this neglect, the Indian towns at

San Juan Capistrano,

San Dieguito, and

Las Flores did continue on for some time under a provision in Governor Echeandía's 1826 Proclamation that allowed for the partial conversion of missions to new ''pueblos''. After the secularizing of the Missions, many of the surviving Mission Indians switched from being unpaid workers for the missions to unpaid laborers and vaqueros (cowboys) of the about 500 large Californio owned

ranchos.

Rancho grants

Before Alta California became a part of the Mexican state, about 30 Spanish land grants had already been deeded in all of

Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

to Presidio soldiers and government officials and a few friends and family of the Alta California Governors, some of whom were grandchildren of the original 1775 Anza expedition settlers. The 1824 Mexican Colony Law established rules for petitioning for land grants in California; and by 1828, the rules for establishing land grants were codified in the Mexican Reglamento (Regulation). The Acts sought to break the monopoly of the Franciscan missions, while paving the way for additional settlers to California by making land grants easier to obtain.

When the missions were secularized, the mission property and cattle were supposed to be mostly allocated to the Mission Indians. In practice, nearly all mission property and livestock were taken over by the about 455 large

ranchos granted by the governors—mostly to friends and family at low or no cost. The rancho owners claimed about averaging about each. This land was nearly all distributed on former mission land within about of the coast.

The Mexican land grants were provisional until settled and worked on for five years, and often had very indefinite boundaries and sometimes conflicting ownership claims. The boundaries of each rancho were almost never surveyed, and marked, and often depended on local landmarks that often changed over time. Since the government depended on import tariffs for its income, there was virtually no property tax—the property tax when introduced with U.S. statehood was a big shock. The grantee could not subdivide, or rent out, the land without approval.

The rancho owners tried to live in a grand manner, and the result was similar to a

barony Barony may refer to:

* Barony, the peerage, office of, or territory held by a baron

* Barony, the title and land held in fealty by a feudal baron

* Barony (county division), a type of administrative or geographical division in parts of the British ...

. Much of the agriculture, vineyards, and orchards established by the Missions were allowed to deteriorate as the rapidly declining Mission Indian population required less food, and the Missionaries and soldiers supporting the Missions disappeared. The new Ranchos and slowly increasing Pueblos mostly only grew enough food to eat and to trade with the occasional trading ship or

whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

that put into a California port to trade, get fresh water, replenish their firewood and obtain fresh vegetables.

The main products of these ranchos were

cattle hides (called California greenbacks) and

tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton suet, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton suet. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain technical criteria, inc ...

(rendered fat for making candles and soap) that were traded for other finished goods and merchandise. This hide-and-tallow trade was mainly carried on by Boston-based ships that traveled to around

Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

to bring finished goods and merchandise to trade with the Californio Ranchos for their hides and tallow. The cattle and horses that provided the hides and tallow essentially grew wild.

By 1845, the province of Alta California had a non-native population of about 1,500 Spanish and Latin American-born adult men along with about 6,500 women and their California-born children (who became the Californios). These Spanish-speakers lived mostly in the southern half of the state from San Diego north to Santa Barbara. There were also around 1,300 American immigrants and 500 European immigrants from a wide variety of backgrounds. Nearly all of these were adult males and a majority lived in central and northern California, from Monterey north to Sonoma and east to the

Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada ( ) is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primari ...

foothills.

A large non-coastal land grant was given to

John Sutter

John Augustus Sutter (February 23, 1803 – June 18, 1880), born Johann August Sutter and known in Spanish as Don Juan Sutter, was a Switzerland, Swiss immigrant who became a Mexican and later an American citizen, known for establishing Sutter ...

who, in 1839, settled a large land grant close to the future city of

Sacramento, California

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of California and the county seat, seat of Sacramento County, California, Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento Rive ...

, which he called "

New Helvetia

New Helvetia ( Spanish: Nueva Helvetia), meaning "New Switzerland", was a 19th-century Alta California settlement and rancho, centered in present-day Sacramento, California.

Colony of Nueva Helvetia

The Swiss pioneer John Sutter (1803–1880 ...

" ("New Switzerland"). There, he built an extensive fort equipped with much of the armament from

Fort Ross

Fort Ross (, , Kashaya: ) is a former Russian establishment on the west coast of North America in what is now Sonoma County, California. Owned and operated by the Russian-American Company, it was the hub of the southernmost Russian settlemen ...

—bought from the Russians on credit when they abandoned that fort.

Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican ''Alta California'' province. Established in 1839, the site of the fort was originally part of a utopian colonial project called New Helvetia (''New Switzerland'') ...

was the first non-

Native American community in the California

Central Valley. Sutter's Fort, from 1839 to about 1848, was a major agricultural and trade colony in California, often welcoming and assisting

California Trail

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about across the western half of the North American continent from Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California. After it was established, the first half of the California Trail f ...

travelers to California. Most of the settlers at, or near, Sutter's Fort were new immigrants from the United States.

Conquest of California (1846–1847)

Hostilities between the U.S. and Mexico were sparked in part by territorial disputes between Mexico and the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

, and later by the American

annexation of Texas in 1845. Several battles between U.S. and Mexican troops led the United States Congress to issue a declaration of war against Mexico on May 13, 1846; the

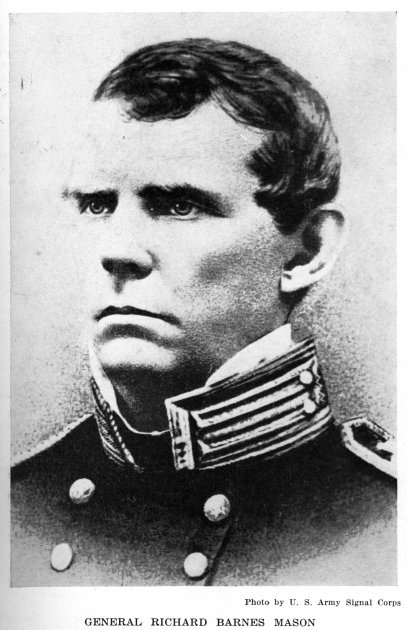

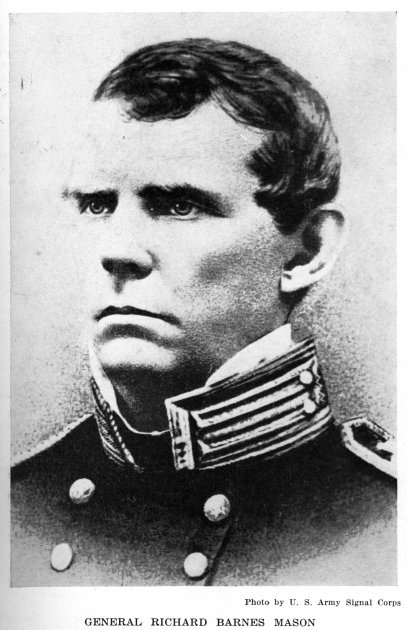

Mexican–American War