CIO-PAC on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The first-ever "political action committee" in the United States of America was the

In his 1993 memoir, John Abt, general counsel for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America under

In his 1993 memoir, John Abt, general counsel for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America under  In November 1946, prior to passage of the Smith–Connally Act, the CIO's second president, Philip Murray appointed John Brophy (a UMW leader, by then head of the CIO's director of Industrial Union Councils), Nathan Cowan (CIO legislative director), and J. Raymond Walsh (CIO research director) to report on CIO political operations. Their report of December 1946 included recommendation for a permanent CIO national political group and consideration for formation of an American Labor Party. During CIO Executive Board meetings in January and February 1943, the board approved most recommendations.

In November 1946, prior to passage of the Smith–Connally Act, the CIO's second president, Philip Murray appointed John Brophy (a UMW leader, by then head of the CIO's director of Industrial Union Councils), Nathan Cowan (CIO legislative director), and J. Raymond Walsh (CIO research director) to report on CIO political operations. Their report of December 1946 included recommendation for a permanent CIO national political group and consideration for formation of an American Labor Party. During CIO Executive Board meetings in January and February 1943, the board approved most recommendations.

Upon passage of the Smith–Connally Act on June 25, 1943, Murray called for a political action committee. The CIO-PAC formed in July 1943 to support the fourth candidacy of

Upon passage of the Smith–Connally Act on June 25, 1943, Murray called for a political action committee. The CIO-PAC formed in July 1943 to support the fourth candidacy of

Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of Labor unions in the United States, unions that organized workers in industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in ...

– Political Action Committee

In the United States, a political action committee (PAC) is a tax-exempt 527 organization that pools campaign contributions from members and donates those funds to campaigns for or against candidates, ballot initiatives, or legislation. The l ...

or CIO-PAC (1943–1955). What distinguished the CIO-PAC from previous political groups (including the AFL's political operations) was its "open, public operation, soliciting support from non-CIO unionists and from the progressive public. ... Moreover, CIO political operatives would actively participate in intraparty platform, policy, and candidate selection processes, pressing the broad agenda of the industrial union movement."

Background

In his 1993 memoir, John Abt, general counsel for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America under

In his 1993 memoir, John Abt, general counsel for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America under Sidney Hillman

Sidney Hillman (March 23, 1887 – July 10, 1946) was an American labor leader. He was the head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and was a key figure in the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and in marshaling labor ...

, claimed the leaders of the Communist Party of the USA had inspired the idea of the CIO-PAC: In 1943, Gene Dennis came to me and Lee Pressman to first raise the idea of a political action committee to organize labor support for Roosevelt in the approaching 1944 election. Pressman approached Murray with the idea, as I did with Hillman. Both men seized upon the proposal with great enthusiasm.Abt and Pressman become the CIO-PAC's co-counsels. Momentum for the CIO-PAC came from the Smith–Connally Act or War Labor Disputes ActMalsberger, ''From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938–1952'', 2000, p. 104. (50 U.S.C. App. 1501 et seq.) was an American law passed on June 25, 1943, over President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's veto. The legislation was hurriedly created after 400,000 coal miners, their wages significantly lowered because of high wartime inflation, struck Struck is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Adolf Struck

Adolf Hermann Struck (1877–1911) was a German sightseer and writer. He is known for his Travel literature, travelogue ''Makedonische Fahrten'' and for surveying the ...

for a $2-a-day wage increase. The Act allowed the federal government to seize and operate industries threatened by or under strikes that would interfere with war production, and prohibited unions from making contributions in federal elections.

The war powers bestowed by the Act were first used in August 1944 when the Fair Employment Practices Commission ordered the Philadelphia Transportation Company

The Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) was the main public transit operator in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1940 to 1968. A private company, PTC was the successor to the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company (PRT), in operation since ...

to hire African-Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

as motormen. The 10,000 members of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union (PRTEU), a labor union unaffiliated with either the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

or the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of Labor unions in the United States, unions that organized workers in industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in ...

, led a sick-out strike, now known as the Philadelphia transit strike of 1944, for six days. President Roosevelt sent 8,000 United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

troops to the city to seize and operate the transit system, and threatened to draft any PRTEU member who did not return to the job within 48 hours. Roosevelt's actions broke the strike.

In November 1946, prior to passage of the Smith–Connally Act, the CIO's second president, Philip Murray appointed John Brophy (a UMW leader, by then head of the CIO's director of Industrial Union Councils), Nathan Cowan (CIO legislative director), and J. Raymond Walsh (CIO research director) to report on CIO political operations. Their report of December 1946 included recommendation for a permanent CIO national political group and consideration for formation of an American Labor Party. During CIO Executive Board meetings in January and February 1943, the board approved most recommendations.

In November 1946, prior to passage of the Smith–Connally Act, the CIO's second president, Philip Murray appointed John Brophy (a UMW leader, by then head of the CIO's director of Industrial Union Councils), Nathan Cowan (CIO legislative director), and J. Raymond Walsh (CIO research director) to report on CIO political operations. Their report of December 1946 included recommendation for a permanent CIO national political group and consideration for formation of an American Labor Party. During CIO Executive Board meetings in January and February 1943, the board approved most recommendations.

Formation

Upon passage of the Smith–Connally Act on June 25, 1943, Murray called for a political action committee. The CIO-PAC formed in July 1943 to support the fourth candidacy of

Upon passage of the Smith–Connally Act on June 25, 1943, Murray called for a political action committee. The CIO-PAC formed in July 1943 to support the fourth candidacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

for U.S. President in 1944 toward the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It also provided financial assistance to other CIO-endorsed political candidates and pro-labor legislation (e.g., continuation of the Wagner Act against the Taft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act, 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

in 1947). CIO member unions funded it. Its first head was Sidney Hillman

Sidney Hillman (March 23, 1887 – July 10, 1946) was an American labor leader. He was the head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and was a key figure in the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and in marshaling labor ...

, founder and head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, from 1943 to 1946.

First members of the CIO-PAC included the following:

* Sidney Hillman

Sidney Hillman (March 23, 1887 – July 10, 1946) was an American labor leader. He was the head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and was a key figure in the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and in marshaling labor ...

, chairman (founder and head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America or ACW)

* R. J. Thomas, treasurer (president of the United Auto Workers

The United Auto Workers (UAW), fully named International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) and sou ...

or UAW)

* Vann Bittner, member (national organizer for the United Mine Workers

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American Labor history of the United States, labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing work ...

or UMW)

* Sherman Dalrymple, member (president of the United Rubber Workers) or URW)

* Albert Fitzgerald, member (president of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America or UE)

* David McDonald, member (secretary-treasurer of the United Steel Workers of America or USWA)

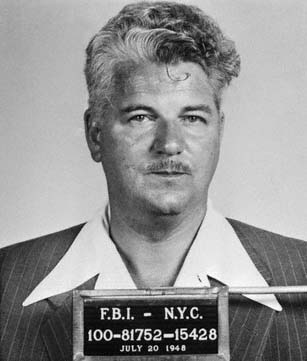

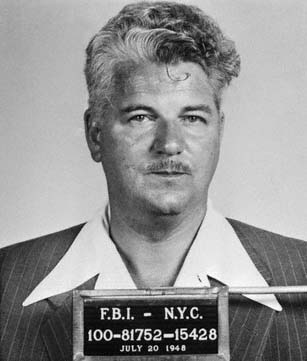

John Abt and Lee Pressman became the CIO-PAC's co-counsels. Calvin Benham Baldwin left government at that time to go work for the CIO-PAC. (By August 1948, the ''Washington Post'' had dubbed Baldwin along with John Abt and Lee Pressman (the latter two members of the Soviet underground Ware Group involved in the Hiss

Hiss or Hissing may refer to:

* Hiss (electromagnetic), a wave generated in the plasma of the Earth's ionosphere or magnetosphere

* Hiss (surname)

* ''Hissing'' (manhwa), a Korean manhwa series by Kang EunYoung

* Noise (electronics) or electro ...

- Chambers Case) as "influential insiders" and "stage managers" in the Wallace presidential campaign.)

20th century

After 1944, Lucy Randolph Mason worked with the CIO-PAC in the South, helping to register union members, black and white, and working for the elimination of thepoll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

. She also forged lasting links between labor and religious groups.

On October 17, 1950, New York State Supreme Court Judge Ferdinand Pecora

Ferdinand Pecora (January 6, 1882 – December 7, 1971) was an American lawyer and New York State Supreme Court judge who became famous in the 1930s as Chief Counsel to the United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency during its invest ...

and US Senator Herbert H. Lehman (D-NY) gave radio addresses on behalf of the CIO-PAC during prime (10:30–11:15 pm.).

In 1955, when the CIO rejoined the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

to form the AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

, Jack Kroll became head of the CIO-PAC, which merged with the AFL's "League for Political Education" to form the AFL–CIO Committee on Political Education.

21st century

PAC activities by AFL–CIO and its members continue into the 21st century. In 2015, an AFL–CIO's moratorium on federal PAC contributions by its member unions began to fall apart weeks after its announcement. Defiant unions included:United Food and Commercial Workers

The United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) is a trade union, labor union representing approximately 1.3 million workers in the United States and Canada in industries including retail; meatpacking, food processing and manufa ...

, the International Association of Machinists

The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM) is an AFL–CIO/ CLC trade union representing over 600,000 workers as of 2024 in more than 200 industries with most of its membership in the United States and Canada.

Origi ...

, and the Laborers' International Union of North America–13% were non-compliant.

References

External sources

* * * {{Authority control United States political action committees Organizations established in 1943 1943 establishments in the United States Organizations disestablished in 1955 1955 disestablishments in the United States