Bushranger Films on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bushrangers were originally escaped convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia who used

Bushrangers were originally escaped convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia who used

"Bushrangers in the Australian Dictionary of Biography"

Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

Bushranging began soon after British settlement with the establishment of

Bushranging began soon after British settlement with the establishment of  Convict bushrangers were particularly prevalent in the penal colony of

Convict bushrangers were particularly prevalent in the penal colony of

The bushrangers' heyday was the

The bushrangers' heyday was the  Bushranging numbers flourished in

Bushranging numbers flourished in

The increasing push of settlement, increased police efficiency, improvements in

The increasing push of settlement, increased police efficiency, improvements in

In Australia, bushrangers often attract public sympathy (cf. the concept of social bandits). In

In Australia, bushrangers often attract public sympathy (cf. the concept of social bandits). In

Jack Donahue was the first bushranger to have inspired

Jack Donahue was the first bushranger to have inspired

Although not the first Australian film with a bushranging theme, ''

Although not the first Australian film with a bushranging theme, ''

, Australian Screen. Retrieved 8 October 2015. ''Dan Morgan (film), Dan Morgan'' (1911) is notable for portraying its title character as an insane villain rather than a figure of romance. Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner, Captain Starlight, and numerous other bushrangers also received cinematic treatments at this time. Alarmed by what they saw as the glorification of outlawry, state governments bushranger ban, imposed a ban on bushranger films in 1912, effectively removing "the entire folklore relating to bushrangers ... from the most popular form of cultural expression." It is seen as a major reason for the collapse of a booming Australian film industry.Reade, Eric (1970) ''Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1926''. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press, 59. See als

Routt, William D. More Australian than Aristotelian:The Australian Bushranger Film, 1904–1914. ''Senses of Cinema'' 18 (January–February), 2002

. The banning of bushranger films in NSW is fictionalised in Kathryn Heyman's 2006 novel, ''Captain Starlight's Apprentice''. One of the few Australian films to escape the ban before it was lifted in the 1940s is the Robbery Under Arms (1920 film), 1920 adaptation of ''Robbery Under Arms''. Also during this lull appeared American takes on the bushranger genre, including ''The Bushranger (1928 film), The Bushranger'' (1928), ''Stingaree (1934 film), Stingaree'' (1934) and ''Captain Fury'' (1939). ''Ned Kelly (1970 film), Ned Kelly'' (1970) starred Mick Jagger in the title role. Dennis Hopper portrayed Dan Morgan in ''Mad Dog Morgan'' (1976). More recent bushranger films include Ned Kelly (2003 film), ''Ned Kelly'' (2003), starring Heath Ledger, ''The Proposition (2005 film), The Proposition'' (2005), written by Nick Cave, ''The Outlaw Michael Howe'' (2013), and ''The Legend of Ben Hall'' (2016).

Bushrangers trail at Picture AustraliaBushrangers at Australianhistory websiteBushrangers on the National Museum of Australia website

{{Authority control Bushrangers, * History of Australia (1788–1850) History of Australia (1851–1900) Robbers

Bushrangers were originally escaped convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia who used

Bushrangers were originally escaped convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia who used the bush

"The bush" is a term mostly used in the English vernacular of Australia and New Zealand where it is largely synonymous with ''backwoods'' or '' hinterland'', referring to a natural undeveloped area. The fauna and flora contained within this ...

as a refuge to hide from the authorities. By the 1820s, the term had evolved to refer to those who took up " robbery under arms" as a way of life, using the bush as their base.

Bushranging thrived during the gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

years of the 1850s and 1860s when the likes of Ben Hall, Bluecap, and Captain Thunderbolt

Frederick Wordsworth Ward (1835 – 25 May 1870), better known by the self-styled pseudonym of Captain Thunderbolt, was an Australian bushranger renowned for escaping from Cockatoo Island, and also for his reputation as the "gentleman bushran ...

roamed the country districts of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. These " Wild Colonial Boys", mostly Australian-born sons of convicts, were roughly analogous to British "highwaymen

A highwayman was a robber who stole from travellers. This type of thief usually travelled and robbed by horse as compared to a footpad who travelled and robbed on foot; mounted highwaymen were widely considered to be socially superior to foot ...

" and outlaws of the American Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

, and their crimes typically included robbing small-town banks and coach services. In certain cases, such as that of Dan Morgan, the Clarke brothers, and Australia's best-known bushranger, Ned Kelly

Edward Kelly (December 1854 – 11 November 1880) was an Australian bushranger, outlaw, gang leader and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing a suit of bulletproof armour during his final shootout wi ...

, numerous policemen were murdered. The number of bushrangers declined due to better policing and improvements in rail transport and communication technology, such as telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

. Although bushrangers appeared sporadically into the early 20th century, most historians regard Kelly's capture and execution in 1880 as effectively representing the end of the bushranging era.

Bushranging exerted a powerful influence in Australia, lasting for over a century and predominating in the eastern colonies. Its origins in a convict system bred a unique kind of desperado, most frequently with an Irish political background. Native-born bushrangers also expressed nascent Australian nationalist views and are recognised as "the first distinctively Australian characters to gain general recognition." As such, a number of bushrangers became folk hero

A folk hero or national hero is a type of hero – real, fictional or mythological – with their name, personality and deeds embedded in the popular consciousness of a people, mentioned frequently in folk songs, folk tales and other folklore; ...

es and symbols of rebellion against the authorities, admired for their bravery, rough chivalry and colourful personalities. However, in stark contrast to romantic portrayals in the arts and popular culture, bushrangers tended to lead lives that were "nasty, brutish and short", with some earning notoriety for their cruelty and bloodthirst. Australian attitudes toward bushrangers remain complex and ambivalent.

Etymology

The earliest documented use of the term appears in a February 1805 issue of ''The Sydney Gazette

''The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser'' was the first newspaper printed in Australia, running from 5 March 1803 until 20 October 1842. It was a semi-official publication of the government of New South Wales, authorised by Governo ...

'', which reports that a cart had been stopped between Sydney and Hawkesbury Hawkesbury or Hawksbury may refer to:

People

*Baron Hawkesbury, or Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool (1727-1808), English statesman

Places

;Geography

*Hawkesbury Island, an island in British Columbia, Canada

*Hawkesbury Island, Queensland, ...

by three men "whose appearance sanctioned the suspicion of their being bush-rangers".Wilson, Jane (14 April 2015)"Bushrangers in the Australian Dictionary of Biography"

Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

John Bigge

John Thomas Bigge (8 March 1780 – 22 December 1843) was an English judge and royal commissioner. He is mostly known for his inquiry into the British colony of New South Wales published in the early 1820s. His reports favoured a return to the ...

described bushranging in 1821 as "absconding in the woods and living upon plunder and the robbery of orchards." Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

likewise recorded in 1835 that a bushranger was "an open villain who subsists by highway robbery, and will sooner be killed than taken alive".

History

Over 2,000 bushrangers are estimated to have roamed the Australian countryside, beginning with the convict bolters and drawing to a close afterNed Kelly

Edward Kelly (December 1854 – 11 November 1880) was an Australian bushranger, outlaw, gang leader and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing a suit of bulletproof armour during his final shootout wi ...

's last stand at Glenrowan.

Convict era (1780s–1840s)

Bushranging began soon after British settlement with the establishment of

Bushranging began soon after British settlement with the establishment of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

as a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer t ...

in 1788. The majority of early bushrangers were convicts who had escaped prison, or from the properties of landowners to whom they had been assigned as servants. These bushrangers, also known as "bolters", preferred the hazards of wild, unexplored bushland surrounding Sydney to the deprivation and brutality of convict life. The first notable bushranger, African convict John Caesar

John Caesar (1764 – 15 February 1796), nicknamed "Black Caesar", was the first Australian bushranger and one of the first people of African descent to arrive in Australia.

Biography

It is believed that Caesar was born in Madagascar or the We ...

, robbed settlers for food, and had a brief, tempestuous alliance with Aboriginal resistance fighters during Pemulwuy's War. While other bushrangers would go on to fight alongside Indigenous Australian

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples o ...

s in frontier conflicts with the colonial authorities, the Government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government ...

tried to bring an end to any such collaboration by rewarding Aborigines for returning convicts to custody. Aboriginal tracker

Aboriginal trackers were enlisted by Europeans in the years following British colonisation of Australia, to assist them in exploring the Australian landscape. The excellent tracking skills of these Aboriginal Australians were advantageous to s ...

s would play a significant role in the hunt for bushrangers.

Colonel Godfrey Mundy

Major-General Godfrey Charles Mundy (10 March 1804 – 10 July 1860) was a British Army officer who became Lieutenant Governor of Jersey.

Military career

Mundy was commissioned as a lieutenant in the British Army in 1821. He took part in the Sie ...

described convict bushrangers as "desperate, hopeless, fearless; rendered so, perhaps, by the tyranny of a gaoler, of an overseer, or of a master to whom he has been assigned." Edward Smith Hall

Edward Smith Hall (28 March 1786 – 18 September 1860)M. J. B. Kenny,Hall, Edward Smith (1786–1860), '' Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 1, MUP, 1966. Accessed 27 May 2012 was a political reformer, newspaper editor and banker in ...

, editor of early Sydney newspaper '' The Monitor'', agreed that the convict system was a breeding-ground for bushrangers due to its savagery, with starvation and acts of torture being rampant. "Liberty or Death!" was the cry of convict bushrangers, and in large numbers they roamed beyond Sydney, some hoping to reach China, which was commonly believed to be connected by an overland route. Some bolters seized boats and set sail for foreign lands, but most were hunted down and brought back to Australia. Others attempted to inspire an overhaul of the convict system, or simply sought revenge on their captors. This latter desire found expression in the convict ballad "Jim Jones at Botany Bay "Jim Jones at Botany Bay" (Roud 5478) is a traditional Australian folk ballad dating from the early 19th-century. The narrator, Jim Jones, is found guilty of poaching and sentenced to transportation to the penal colony of New South Wales. En route, ...

", in which Jones, the narrator, plans to join bushranger Jack Donahue

John Donahue (c. 1806 – 1 September 1830), also spelled Donohoe, and known as Jack Donahue and Bold Jack Donahue, was an Irish-born bushranger in Australia between 1825 and 1830. He became part of the notorious "Wild Colonial Boys".

Early l ...

and "gun the floggers down".

Donahue was the most notorious of the early New South Wales bushrangers, terrorising settlements outside Sydney from 1827 until he was fatally shot by a trooper in 1830. That same year, west of the Blue Mountains, convict Ralph Entwistle

Ralph Entwistle (1804–2 November 1830) was an English labourer who was transported to the British penal colony of New South Wales as a convict in 1827. As a member of the Ribbon Gang, his escape sparked the Bathurst Rebellion of 1830. He ...

sparked a bushranging insurgency known as the Bathurst Rebellion

The Bathurst rebellion of 1830 was an outbreak of bushranging near Bathurst in the British penal colony (now the Australian state) of New South Wales.

The rebellion involved a group of escaped convicts who ransacked villages and engaged in shooto ...

. He and his gang raided farms, liberating assigned convicts by force in the process, and within a month, his personal army numbered 80 men. Following gun battles with vigilante posses, mounted policemen and soldiers of the 39th and 57th Regiment of Foot

The 57th (West Middlesex) Regiment of Foot was a regiment of line infantry in the British Army, raised in 1755. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 77th (East Middlesex) Regiment of Foot to form the Middlesex Regiment in 1881.

His ...

, he and nine of his men were captured and executed.

Convict bushrangers were particularly prevalent in the penal colony of

Convict bushrangers were particularly prevalent in the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

(now the state of Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

), established in 1803. The island's most powerful bushranger, the self-styled "Lieutenant Governor of the Woods", Michael Howe, led a gang of up to one hundred members "in what amounted to a civil war" with the colonial government. His control over large swathes of the island prompted elite squatters

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

from Hobart and Launceston to collude with him, and for six months in 1815, Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

Thomas Davey, fearing a convict uprising, declared martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in an effort to suppress Howe's influence. Most of the gang had either been captured or killed by 1818, the year Howe was clubbed to death.Boyce, James (2010). ''Van Diemen's Land''. Black Inc.. . pp. 76–82. Vandemonian bushranging peaked in the 1820s with hundreds of bolters at large, among the most notorious being Matthew Brady

Matthew Brady (1799 – 4 May 1826) was an English-born convict who became a bushranger in Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania). He was sometimes known as "Gentleman Brady" due to his good treatment and fine manners when robbing his victims. ...

's gang, cannibal serial killers Alexander Pearce

Alexander Pearce (1790 – 19 July 1824) was an Irish convict who was transported to the penal colony in Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), Australia for seven years for theft. He escaped from prison several times, allegedly becoming a cannibal ...

and Thomas Jeffrey

Thomas Jeffrey (surname also recorded as Jeffery, Jeffries, Jeffreys or Jefferies) was a convict bushranger, murderer and cannibal in the mid-1820s in Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania, Australia). In contemporary newspaper reports of his crim ...

, and tracker-turned-resistance leader Musquito

Musquito (c. 1780, Port Jackson – 25 February 1825, Hobart) (also rendered Mosquito, Musquetta, Bush Muschetta or Muskito) was an Indigenous Australian resistance leader, latterly based in Van Diemen's Land.

New South Wales and Norfolk Islan ...

. Jackey Jackey

Jackey Jackey (also spelled Jacky Jacky) (1833–1854) is the name by which Galmahra (a.k.a. Galmarra), the Aboriginal Australian guide and companion to surveyor Edmund Kennedy was known. He survived Edmund Kennedy's fatal 1848 expedition into ...

(alias of William Westwood) was sent from New South Wales to Van Diemen's Land in 1842 after attempting to escape Cockatoo Island. In 1843, he escaped Port Arthur, and took up bushranging in Tasmania's mountains, but was recaptured and sent to Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together w ...

, where, as leader of the 1846 Cooking Pot Uprising

The Cooking Pot Uprising or Cooking Pot Riot was an uprising of convicts led by William Westwood in the penal colony of Norfolk Island, Australia. It occurred on 1 July 1846 in response to the confiscation of convicts' cooking vessels under ...

, he murdered three constables, and was hanged along with sixteen of his men.

The era of convict bushrangers gradually faded with the decline in penal transportations to Australia in the 1840s. It had ceased by the 1850s to all colonies except Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to ...

, which accepted convicts between 1850 and 1868. The best-known convict bushranger of the colony was the prolific escapee Moondyne Joe.

Gold rush era (1850s–1860s)

The bushrangers' heyday was the

The bushrangers' heyday was the Gold Rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

years of the 1850s and 1860s as the discovery of gold gave bushrangers access to great wealth that was portable and easily converted to cash. Their task was assisted by the isolated location of the goldfields and a police force decimated by troopers abandoning their duties to join the gold rush.

George Melville was hanged in front of a large crowd for robbing the McIvor gold escort near Castlemaine Castlemaine may mean:

* Castlemaine, Victoria, a town in Victoria, Australia

** Castlemaine Football Club, an Australian rules football club

** Castlemaine railway station

* Castlemaine, County Kerry, a town in Ireland

* Castlemaine Brewery, Western ...

in 1853.

Bushranging numbers flourished in

Bushranging numbers flourished in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

with the rise of the colonial-born sons of poor, often ex-convict squatters who were drawn to a more glamorous life than mining or farming.

Much of the activity in this era was in the Lachlan Valley, around Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine owned by Integrated Whale Media Investments and the Forbes family. Published eight times a year, it features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. ''Forbes'' also r ...

, Yass and Cowra

Cowra is a small town in the Central West region of New South Wales, Australia. It is the largest population centre and the council seat for the Cowra Shire, with a population of 9,863.

Cowra is located approximately above sea level, on the ...

.

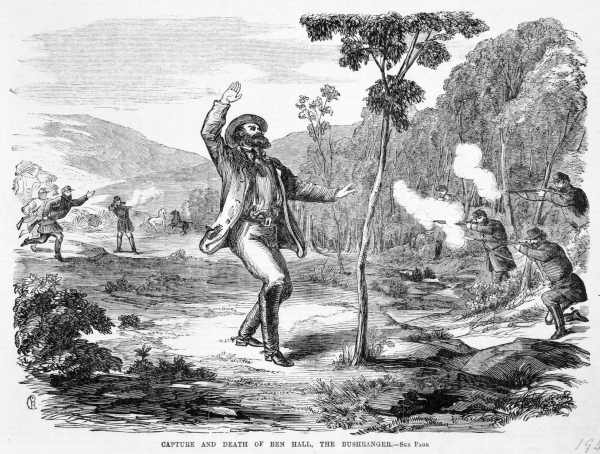

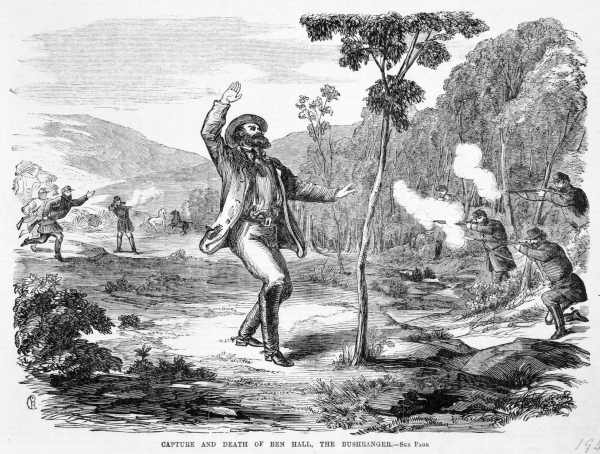

The Gardiner–Hall gang

The Gardiner–Hall Gang was an informal group of bushrangers who roamed the central west of New South Wales, Australia in the 1860s. Named after leaders Frank Gardiner and Ben Hall, the gang was responsible for the largest gold robbery in Aust ...

, led by Frank Gardiner

Frank Gardiner (1830 – c. 1882) was an Australian bushranger who gained infamy for his lead role in the a robbery of a gold escort at Eugowra, New South Wales in June 1862. It is considered the largest gold heist in Australian history. Gard ...

and Ben Hall and counting John Dunn John, Jack, Johnny, Jon, or Jonathan Dunn may refer to:

Entertainment

*John Dunn (pipemaker) (c. 1764–1820), inventor of keyed Northumbrian smallpipes

*John Dunn (actor) born O'Donoghue (1813–1875), Australian comic actor

*John Millard Dunn (1 ...

, John Gilbert and Fred Lowry

Thomas Frederick Lowry (''c''. 1836 – 30 August 1863), better known as Fred Lowry, was an Australian bushranger.

Born in New South Wales, Lowry was imprisoned at Cockatoo Island in 1858 for horse theft, and soon after his release a few year ...

among its members, was responsible for some of the most daring robberies of the 1860s, including the 1862 Escort Rock robbery, Australia's largest ever gold heist. The gang also engaged in many shootouts with the police, resulting in deaths on both sides. Other bushrangers active in New South Wales during this period, such as Dan Morgan, and the Clarke brothers and their associates, murdered multiple policemen.

As bushranging continued to escalate in the 1860s, the Parliament of New South Wales

The Parliament of New South Wales is a bicameral legislature in the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW), consisting of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (lower house) and the New South Wales Legislative Council (upper house). Each ...

passed a bill, the ''Felons Apprehension Act 1865'', that effectively allowed anyone to shoot outlawed bushrangers on sight. By the time that the Clarke brothers were captured and hanged in 1867, organised gang bushranging in New South Wales had effectively ceased.

Captain Thunderbolt

Frederick Wordsworth Ward (1835 – 25 May 1870), better known by the self-styled pseudonym of Captain Thunderbolt, was an Australian bushranger renowned for escaping from Cockatoo Island, and also for his reputation as the "gentleman bushran ...

(alias of Frederick Ward) robbed inns and mail-coaches across northern New South Wales for six and a half years, one of the longest careers of any bushranger. He sometimes operated alone; at other times, he led gangs, and was accompanied by his Aboriginal 'wife', Mary Ann Bugg

Mary Ann Bugg (7 May 1834 – 22 April 1905) was a Worimi bushranger, one of two notable female bushrangers in mid-19th century Australia. She was an expert horse rider and bush navigator who travelled with her bushranging partner and lover Captai ...

, who is credited with helping extend his career.

Decline and the Kelly gang (1870s–1880s)

The increasing push of settlement, increased police efficiency, improvements in

The increasing push of settlement, increased police efficiency, improvements in rail transport

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in Track (rail transport), tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the ...

and communications technology, such as telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

, made it more difficult for bushrangers to evade capture. In 1870, Captain Thunderbolt was fatally shot by a policeman, and with his death, the New South Wales bushranging epidemic that began in the early 1860s came to an end.

The scholarly, but eccentric Captain Moonlite

Andrew George Scott (5 July 1842 – 20 January 1880), also known as Captain Moonlite, though also referred to as Alexander Charles Scott and Captain Moonlight, was an Irish-born New Zealand immigrant to the Colony of Victoria, a bushranger ther ...

(alias of Andrew George Scott) worked as an Anglican lay reader

In Anglicanism, a licensed lay minister (LLM) or lay reader (in some jurisdictions simply reader) is a person authorised by a bishop to lead certain services of worship (or parts of the service), to preach and to carry out pastoral and teaching ...

before turning to bushranging. Imprisoned in Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) is a city in the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 Census, Ballarat had a population of 116,201, making it the third largest city in Victoria. Estimated resident population, 30 June 2018.

Within months of Vi ...

for an armed bank robbery on the Victorian goldfields, he escaped, but was soon recaptured and received a ten-year sentence in HM Prison Pentridge

HM Prison Pentridge was an Australian prison that was first established in 1851 in Coburg, Victoria. The first prisoners arrived in 1851. The prison officially closed on 1 May 1997.

Pentridge was often referred to as the "Bluestone College", ...

. Within a year of his release in 1879, he and his gang held up the town of Wantabadgery

Wantabadgery is a village community in the central eastern part of the Riverina situated about 35 kilometres east of Wagga Wagga and 19 kilometres west of Nangus. At the , Wantabadgery had a population of 299.

Wanta Badgery Post Offic ...

in the Riverina

The Riverina

is an agricultural region of south-western New South Wales, Australia. The Riverina is distinguished from other Australian regions by the combination of flat plains, warm to hot climate and an ample supply of water for irrigation ...

. Two of the gang (including Moonlite's "soulmate" and alleged lover, James Nesbitt) and one trooper were killed when the police attacked. Scott was found guilty of murder and hanged along with one of his accomplices on 20 January 1880.

Among the last bushrangers was the Kelly gang in Victoria, led by Ned Kelly

Edward Kelly (December 1854 – 11 November 1880) was an Australian bushranger, outlaw, gang leader and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing a suit of bulletproof armour during his final shootout wi ...

, Australia's most famous bushranger. After murdering three policemen in a shootout in 1878, the gang was outlawed, and after raiding towns and robbing banks into 1879, earned the distinction of having the largest reward ever placed on the heads of bushrangers. In 1880, after failing to derail and ambush a police train, the gang, clad in bulletproof armour they had devised, engaged in a shootout with the police. Ned Kelly, the only gang member to survive, was hanged at the Melbourne Gaol

The Old Melbourne Gaol is a former jail and current museum on Russell Street, in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It consists of a bluestone building and courtyard, and is located next to the old City Police Watch House and City Courts build ...

in November 1880.

Isolated outbreaks (1890s–1900s)

In July 1900, the Governor brothers—a trio group consisting of an Aboriginal fencing contractor namedJimmy Governor

Jimmy Governor (1875 – 1901) was an Indigenous Australian who was proclaimed an outlaw after committing a series of murders in 1900. His actions initiated a cycle of violence in which nine people were killed (either by Governor or his accomp ...

and his associates, Joe Governor and Jack Underwood—perpetrated the Breelong Massacre, wounding one and killing five members of the Mawbey family.

The massacre sparked the Governor brothers to engage in a crime spree across northern New South Wales, triggering one of the largest manhunts in Australian history, with 2,000 armed civilians and police covering 3,000 km of northern New South Wales in a search for the brothers. The Governor brothers were pursued by authorities for a total of three months, consequently being brought down on 27 October with the arrest of Jimmy Governor by a group of armed locals in Bobin, NSW, and the death of his brother, Joe Governor, near Singleton, NSW

Singleton is a town on the banks of the Hunter River (New South Wales), Hunter River in New South Wales, Australia. Singleton is 197 km (89 mi) north-north-west of Sydney, and 70 km (43 mi) north-west of Newcastle, New South ...

a few days later.

Jack Underwood (who had been caught shortly after the Breelong Massacre) was hanged in Dubbo Gaol

The Old Dubbo Gaol is a heritage-listed former gaol and now museum and tourist attraction at 90 Macquarie Street, Dubbo in the Dubbo Regional Council local government area of New South Wales, Australia. The gaol was designed by the NSW Colonia ...

on 14 January 1901, and Jimmy Governor was hanged in Darlinghurst Gaol

The Darlinghurst Gaol is a former Australian prison located in Darlinghurst, New South Wales. The site is bordered by Darlinghurst Road, Burton and Forbes streets, with entrances on Forbes and Burton Streets. The heritage-listed building, predo ...

on 18 January 1901.

"Boy bushrangers" (1910s–1920s)

The final phase of bushranging was sustained by the so-called "boy bushrangers"—youths who sought to commit crimes, mostly armed robberies, modelled on the exploits of their bushranging "heroes". The majority were captured alive without any fatalities.Public perception

In Australia, bushrangers often attract public sympathy (cf. the concept of social bandits). In

In Australia, bushrangers often attract public sympathy (cf. the concept of social bandits). In Australian history

The history of Australia is the story of the land and peoples of the continent of Australia.

Aboriginal Australians, People first arrived on the Australian mainland by sea from Maritime Southeast Asia between 50,000 and 65,000 years ago, and ...

and iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

bushrangers are held in some esteem in some quarters due to the harshness and anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

of the colonial authorities whom they embarrassed, and the romanticism of the lawlessness they represented. Some bushrangers, most notably Ned Kelly

Edward Kelly (December 1854 – 11 November 1880) was an Australian bushranger, outlaw, gang leader and convicted police-murderer. One of the last bushrangers, he is known for wearing a suit of bulletproof armour during his final shootout wi ...

in his Jerilderie letter

The handwritten document known as the Jerilderie Letter was dictated by Australian bushranger Ned Kelly to fellow Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne in 1879. It is one of only two original Kelly letters known to have survived.

The Jerilderie Letter is ...

, and in his final raid on Glenrowan, explicitly represented themselves as political rebels. Attitudes to Kelly, by far the most well-known bushranger, exemplify the ambivalent views of Australians regarding bushranging.

Legacy

The impact of bushrangers upon the areas in which they roamed is evidenced in the names of many geographical features in Australia, including Brady's Lookout,Moondyne Cave

Moondyne Cave is a Karst topography, karst cave in the South West (Western Australia), South West region of Western Australia. It is located on Caves Road (Western Australia), Caves Road, north of Augusta, Western Australia, Augusta.

It has a ...

, the township of Codrington, Mount Tennent

Mount Tennent (Aboriginal: ') is a mountain with an elevation of in the southern part of the Australian Capital Territory in Australia. The Gudgenby River flows at the base of the mountain.

Location and features

Mount Tennent is named aft ...

, Thunderbolts Way

Thunderbolts Way (and at its northern end as Bundarra Road) is a country road located in the Northern Tablelands region of New South Wales, Australia, linking Inverell via Bundarra, Uralla and Walcha to Gloucester The road is partially s ...

and Ward's Mistake. The districts of North East Victoria

North East Victoria is an Australian Geographical Indication for a wine zone in the Australian state of Victoria. It includes five named wine regions:

* Alpine Valleys

* Beechworth

* Glenrowan

* King Valley

* Rutherglen

Geography

The North ...

are unofficially known as Kelly Country.

Some bushrangers made a mark on Australian literature

Australian literature is the literature, written or literary work produced in the area or by the people of the Australia, Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding colonies. During its early Western civilisation, Western history, Australia was ...

. While running from soldiers in 1818, Michael Howe dropped a knapsack containing a self-made book of kangaroo skin and written in kangaroo blood. In it was a dream diary

A dream diary (or dream journal) is a diary in which dream experiences are recorded. A dream diary might include a record of nightly dreams, personal reflections and waking dream experiences. It is often used in the study of dreams and psychology. ...

and plans for a settlement he intended to found in the bush. Sometime bushranger Francis MacNamara, also known as Frank the Poet

Francis MacNamara (ca. 1810 - 28 August 1861), known as Frank the Poet, was an Irish writer, a convict, transported to the Colony of New South Wales, Australia from Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland, he composed improvised verse expressing ...

, wrote some of the best-known poems of the convict era. Several convict bushrangers also wrote autobiographies, including Jackey Jackey, Martin Cash

Martin Cash (baptised 10 October 1808 – 26 August 1877) was a notorious Irish-Australian convict bushranger, known for escaping twice from Port Arthur, Van Diemen's Land. His 1870 autobiography, ''The Adventures of Martin Cash'', ghostwritten ...

and Owen Suffolk

Owen Hargrave Suffolk (4 April 1829 – ? ) was an Australian bushranger, poet, confidence-man and author of ''Days of Crime and Years of Suffering'' (1867).

Early life

Owen Henry Suffolk was born on 4 April 1829 in comfortable circumstances in ...

.

Cultural depictions

Jack Donahue was the first bushranger to have inspired

Jack Donahue was the first bushranger to have inspired bush ballad

The bush ballad, bush song or bush poem is a style of poetry and folk music that depicts the life, character and scenery of the Australian bush. The typical bush ballad employs a straightforward rhyme structure to narrate a story, often one of ...

s, including "Bold Jack Donahue" and "The Wild Colonial Boy

"The Wild Colonial Boy" is a traditional anonymously penned Irish-Australian folk ballad which tells the story of a bushranger in early colonial Australia who dies during a gunfight with local police. Versions of the ballad give different names fo ...

". Ben Hall and his gang were the subject of several bush ballads, including "Streets of Forbes

"Streets of Forbes" is an Australian folksong

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be c ...

".

Michael Howe inspired the earliest play set in Tasmania, ''Michael Howe: The Terror! of Van Diemen's Land'', which premiered at The Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, not-for-profit producing theatre in Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Theatre. In 1871 it was rebuilt and reopened as the Royal Vi ...

in London in 1821. Other early plays about bushrangers include David Burn

David Burn (c.1799 – 14 June 1875) was a Tasmanian pioneer and dramatist, author of the first Australian drama to be performed on stage, ''The Bushrangers''.

__NOTOC__

Early life

Burn was born in Scotland, the son of David Burn and his wife, J ...

's ''The Bushrangers'' (1829), William Leman Rede

William Leman Rede (31 January 1802 – 3 April 1847), often referred to as simply Leman Rede, was one of the many prolific and successful playwrights who composed farces, melodramas, burlettas (light musical and comedies) and travesties, primar ...

's ''Faith and Falsehood; or, The Fate of the Bushranger'' (1830), William Thomas Moncrieff

William Thomas Moncrieff (24 August 1794 – 3 December 1857) commonly referred as W.T. Moncrieff was an English dramatist and author.

Biography

He was born in London, the son of a Strand tradesman named Thomas. The name Moncrieff he assumed fo ...

's ''Van Diemen's Land: An Operatic Drama'' (1831), '' The Bushrangers; or, Norwood Vale'' (1834) by Henry Melville

Henry Saxelby Melville Wintle (1799 – 22 December 1873), commonly referred to as Henry Melville, was an Australian journalist, author, occultist, and Freemason best remembered for writing the play '' The Bushrangers'',

, and '' The Bushrangers; or, The Tregedy of Donohoe'' (1835) by Charles Harpur

Charles Harpur (23 January 1813 – 10 June 1868) was an Australian poet and playwright. He is regarded as "Australia's most important nineteenth-century poet."

Life

Early life on the Hawkesbury

Harpur was born on 23 January 1813 at Windso ...

.

In the late 19th century, E. W. Hornung

Ernest William Hornung (7 June 1866 – 22 March 1921) was an English author and poet known for writing the A. J. Raffles series of stories about a gentleman thief in late 19th-century London. Hornung was educated at Uppingham School; ...

and Hume Nisbet

James Hume Nisbet (8 August 1849 – 4 June 1923) was a Scottish-born novelist and artist. Many of his thrillers are set in Australia.

Youth

Nisbet was born in Stirling, Scotland and received special artistic training, and was educated under the ...

created popular bushranger novels within the conventions of the European "noble bandit" tradition. First serialised in ''The Sydney Mail

''The Sydney Mail'' was an Australian magazine published weekly in Sydney. It was the weekly edition of ''The Sydney Morning Herald'' newspaper and ran from 1860 to 1938.

History

''The Sydney Mail'' was first published on 17 July 1860 by ...

'' in 1882–83, Rolf Boldrewood

Thomas Alexander Browne (born Brown, 6 August 1826 – 11 March 1915) was an Australian author who published many of his works under the pseudonym Rolf Boldrewood. He is best known for his 1882 bushranging novel '' Robbery Under Arms''.

Biog ...

's bushranging novel ''Robbery Under Arms

''Robbery Under Arms'' is a bushranger novel by Thomas Alexander Browne, published under his pen name Rolf Boldrewood. It was first published in serialised form by ''The Sydney Mail'' between July 1882 and August 1883, then in three volumes i ...

'' is considered a classic of Australian colonial literature. It also cited as an important influence on the American writer Owen Wister

Owen Wister (July 14, 1860 – July 21, 1938) was an American writer and historian, considered the "father" of western fiction. He is best remembered for writing '' The Virginian'' and a biography of Ulysses S. Grant.

Biography

Early lif ...

's 1902 novel '' The Virginian'', widely regarded as the first Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

.

Bushrangers were a favoured subject of colonial artists such as S. T. Gill

Samuel Thomas Gill, also known by his signature S.T.G., was an English-born Australian artist.

Early life

Gill was born in Periton, Minehead, Somerset, England, in 1818. He was the son of the Reverend Samuel Gill, a Baptist minister, and his fi ...

, Frank P. Mahony

Francis Prout Mahony, also known as Frank Mahony, (4 December 1862 – 28 June 1916) was an Australian painter, watercolorist and illustrator. Although christened "Francis Mahony", he later added "Prout" and usually signed his work as "Frank P. ...

and William Strutt. Tom Roberts

Thomas William Roberts (8 March 185614 September 1931) was an English-born Australian artist and a key member of the Heidelberg School art movement, also known as Australian impressionism.

After studying in Melbourne, he travelled to Europe ...

, one of the leading figures of the Heidelberg School

The Heidelberg School was an Australian art movement of the late 19th century. It has latterly been described as Australian impressionism.

Melbourne art critic Sidney Dickinson coined the term in an 1891 review of works by Arthur Streeton and ...

(also known as Australian Impressionism

The Heidelberg School was an Australian art movement of the late 19th century. It has latterly been described as Australian impressionism.

Melbourne art critic Sidney Dickinson coined the term in an 1891 review of works by Arthur Streeton a ...

), depicted bushrangers in some of his history paintings, including '' In a corner on the Macintyre'' (1894) and ''Bailed Up

''Bailed Up'' is a 1895 painting by Australian artist Tom Roberts. The painting depicts a stage coach being held up by bushrangers in an isolated, forested section of a back road. The painting is part of the collection of the Art Gallery of N ...

'' (1895), both set in Inverell

Inverell is a large town in northern New South Wales, Australia, situated on the Macintyre River, close to the Queensland border. It is also the centre of Inverell Shire. Inverell is located on the Gwydir Highway on the western slopes of the ...

, the area where Captain Thunderbolt was once active.

Film

Although not the first Australian film with a bushranging theme, ''

Although not the first Australian film with a bushranging theme, ''The Story of the Kelly Gang

''The Story of the Kelly Gang'' is a 1906 Australian bushranger film that traces the exploits of 19th-century bushranger and outlaw Ned Kelly and his gang. It was directed by Charles Tait and shot in and around the city of Melbourne. The origi ...

'' (1906)—the world's first feature-length

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

narrative film

Narrative film, fictional film or fiction film is a motion picture that tells a fictional or fictionalized story, event or narrative. Commercial narrative films with running times of over an hour are often referred to as feature films, or feature ...

—is regarded as having set the template for the genre. On the back of the film's success, its producers released one of two 1907 film adaptations of Boldrewood's ''Robbery Under Arms'' (the other being Charles MacMahon (theatre), Charles MacMahon's Robbery Under Arms (1907 MacMahon film), version). Entering the first "golden age" of Australian cinema (1910–12), director John Gavin (director), John Gavin released two fictionalised accounts of real-life bushrangers: ''Moonlite'' (1910) and ''Thunderbolt (1910 film), Thunderbolt'' (1910). The genre's popularity with audiences led to a spike of production unprecedented in world cinema.Australian film and television chronology: The 1910s, Australian Screen. Retrieved 8 October 2015. ''Dan Morgan (film), Dan Morgan'' (1911) is notable for portraying its title character as an insane villain rather than a figure of romance. Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner, Captain Starlight, and numerous other bushrangers also received cinematic treatments at this time. Alarmed by what they saw as the glorification of outlawry, state governments bushranger ban, imposed a ban on bushranger films in 1912, effectively removing "the entire folklore relating to bushrangers ... from the most popular form of cultural expression." It is seen as a major reason for the collapse of a booming Australian film industry.Reade, Eric (1970) ''Australian Silent Films: A Pictorial History of Silent Films from 1896 to 1926''. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press, 59. See als

Routt, William D. More Australian than Aristotelian:The Australian Bushranger Film, 1904–1914. ''Senses of Cinema'' 18 (January–February), 2002

. The banning of bushranger films in NSW is fictionalised in Kathryn Heyman's 2006 novel, ''Captain Starlight's Apprentice''. One of the few Australian films to escape the ban before it was lifted in the 1940s is the Robbery Under Arms (1920 film), 1920 adaptation of ''Robbery Under Arms''. Also during this lull appeared American takes on the bushranger genre, including ''The Bushranger (1928 film), The Bushranger'' (1928), ''Stingaree (1934 film), Stingaree'' (1934) and ''Captain Fury'' (1939). ''Ned Kelly (1970 film), Ned Kelly'' (1970) starred Mick Jagger in the title role. Dennis Hopper portrayed Dan Morgan in ''Mad Dog Morgan'' (1976). More recent bushranger films include Ned Kelly (2003 film), ''Ned Kelly'' (2003), starring Heath Ledger, ''The Proposition (2005 film), The Proposition'' (2005), written by Nick Cave, ''The Outlaw Michael Howe'' (2013), and ''The Legend of Ben Hall'' (2016).

Notable bushrangers

References

External links

Bushrangers trail at Picture Australia

{{Authority control Bushrangers, * History of Australia (1788–1850) History of Australia (1851–1900) Robbers