Bryan Donkin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bryan Donkin FRS FRAS (22 March 1768 – 27 February 1855) developed the first paper making machine and created the world's first commercial canning factory. These were the basis for large industries that continue to flourish today. Bryan Donkin was involved with Thomas Telford's

Accessed 21 Oct 2023

In the 1820s Donkin became a director of the Thames Tunnel Company, having become acquainted with Marc Brunel when he had supplied equipment for his machinery at

In the 1820s Donkin became a director of the Thames Tunnel Company, having become acquainted with Marc Brunel when he had supplied equipment for his machinery at

Donkin died at home in the New Kent Road, London, on 27 February 1855. He was buried in a vault in

Donkin died at home in the New Kent Road, London, on 27 February 1855. He was buried in a vault in

Britannica article on Donkin

* "Bryan Donkin: The Very Civil Engineer 1768 - 1855" Maureen Greenland and Russ Day, Phillimore Book Publishing, 2016, , 9780993468018

The Bryan Donkin Archive Trust

seeks to ensure that the artefacts of the company are preserved and to educate everyone interested about Bryan Donkin.

AVK

Howden Blowers and Compressors

{{DEFAULTSORT:Donkin, Bryan English inventors English civil engineers People of the Industrial Revolution 1768 births 1855 deaths Fellows of the Royal Society Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers People from Northumberland

Caledonian Canal

The Caledonian Canal connects the Scottish east coast at Inverness with the west coast at Corpach near Fort William in Scotland. The canal was constructed in the early nineteenth century by Scottish engineer Thomas Telford.

Route

The can ...

, Marc and Isambard Brunel's Thames Tunnel, and Charles Babbage's computer. He was an advisor to the government and held in high esteem by his peers.

Early life

Raised in Sandhoe,Northumberland

Northumberland ( ) is a ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North East England, on the Anglo-Scottish border, border with Scotland. It is bordered by the North Sea to the east, Tyne and Wear and County Durham to the south, Cumb ...

, his father was a surveyor and land agent

Land agent may be used in at least three different contexts.

Traditionally, a land agent was a managerial employee who conducted the business affairs of a large landed estate for a member of the nobility or landed gentry, supervising the farming ...

. Donkin initially began work in the same business, and worked from September 1789 to February 1791 as bailiff at Knole House and estate for the Duke of Dorset

Duke of Dorset was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1720 for the politician Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset, Lionel Sackville, 7th Earl of Dorset.

History

The Sackville family descended from Richard Sackville (es ...

.

Career

While working for the Duke of Dorset, Donkin consulted the engineerJohn Smeaton

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792) was an English civil engineer responsible for the design of bridges, canals, harbours and lighthouses. He was also a capable mechanical engineer and an eminent scholar, who introduced various ...

, an acquaintance of his father, as to how he could become an engineer. At Smeaton's advice in 1792 he apprenticed himself to John Hall in Dartford

Dartford is the principal town in the Borough of Dartford, Kent, England. It is located south-east of Central London and

is situated adjacent to the London Borough of Bexley to its west. To its north, across the Thames Estuary, is Thurrock in ...

, Kent, who had founded the Dartford Iron Works (later J & E Hall) in 1785. Shortly after completing his apprenticeship, he set himself up in Dartford, with the support of John Hall, making moulds for paper works, for at that time all paper making was done by hand. In 1798 he married Mary Brames, daughter of Peter Brames, a neighbouring land owner and market gardener, and a prominent supporter of the Methodist movement. By doing so Donkin became brother in law to John Hall, who had married Mary's elder sister Sarah in 1791.

Fourdrinier machine

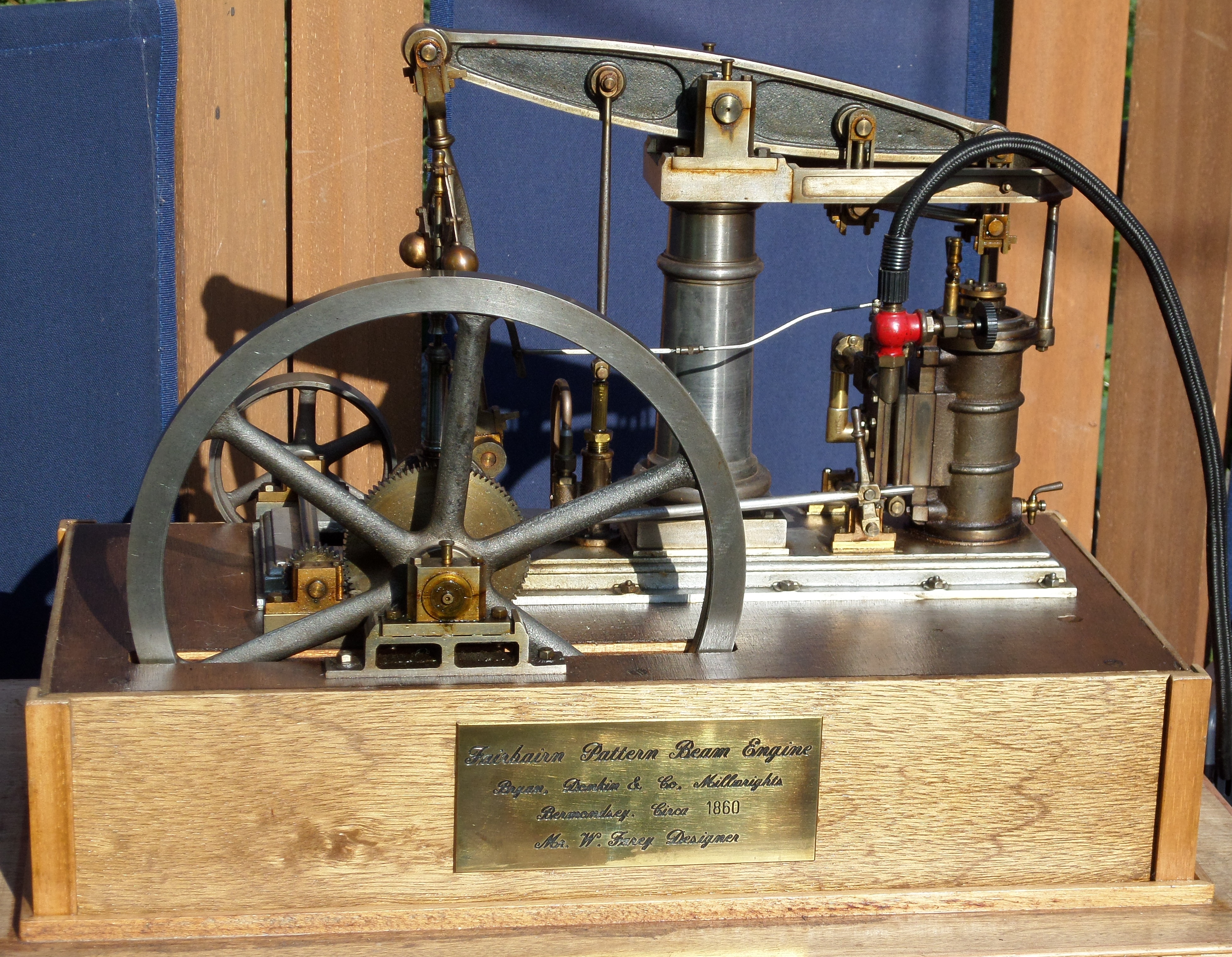

In 1801–2 Donkin took a prototype of a continuous paper-making machine, and started its transformation into the famous Fourdrinier machine which is the basis of modern paper-making. Donkin took premises atBermondsey

Bermondsey ( ) is a district in southeast London, part of the London Borough of Southwark, England, southeast of Charing Cross. To the west of Bermondsey lies Southwark, to the east Rotherhithe and Deptford, to the south Walworth and Peckham, ...

, London in 1802, thus starting the enterprise that became the Bryan Donkin Company, which still continues in business in the early 21st century. In 1804 he succeeded in producing a working machine. A second, improved one, was made the following year and in 1810 eighteen of the complex machines had been erected at various mills. Although the original design was not Donkin's, he received the credit for having perfected them and brought them into use. His company continued to make such machines, and by 1851 had produced nearly 200 machines for use across the world.A Brief Account of Bryan Donkin FRS and of the Company he Founded 150 years ago. Bryan Donkin Company Ltd, Chesterfield, 1953.Accessed 21 Oct 2023

Printing machinery

Donkin also worked with printing machinery. In 1813 he and a printer, Richard Mackenzie Bacon ofNorwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, obtained a patent for a "Polygonal printing machine"; this used types

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

placed on a rotating square or hexagonal roller or " geometric prism". Ink was applied by a roller which rose and fell with the irregularities of the prism. One of these machines was set up for Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. It however proved too complicated and suffered from poor inking, which prevented its success. However, it was the first machine to introduce composition ink rollers which were considered better than the existing leather-covered rollers. Donkin's inking roller quickly became the industry standard.

Tinned food

Donkin became interested incanning

Canning is a method of food preservation in which food is processed and sealed in an airtight container (jars like Mason jars, and steel and tin cans). Canning provides a shelf life that typically ranges from one to five years, although under ...

food in metal containers. John Hall acquired Peter Durand Peter Durand (21 October 1766 – 23 July 1822) was an English merchant who is widely credited with receiving the first patent for the idea of preserving food using tin cans. The patent (No 3372) was granted on August 25, 1810, by King George III ...

's patent in 1812 for the sum of £1000 and after various experiments, and in association with Hall and Gamble, Donkin set up a canning factory in Bermondsey, the first cannery to use tinned iron containers. By late spring 1813 they were appointing agents on the south coast to sell preserved food to outbound ships. Soon the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom that was responsible for the command of the Royal Navy.

Historically, its titular head was the Lord High Admiral of the ...

were placing sizeable orders with the firm of Donkin, Hall and Gamble for meat preserved in tinned iron canisters. The firm of Donkin, Hall and Gamble was later merged into Crosse & Blackwell

Crosse & Blackwell is an English food brand. The original company was established in London in 1706, then was acquired by Edmund Crosse and Thomas Blackwell in 1830. It became independent until it was acquired by Swiss Conglomerate (company), con ...

s. London's Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

has an early Donkin tin can.

Difference engine

During the 1820s and 1830s,Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

requested Donkin's assistance in resolving continuing disputes between Babbage and Joseph Clement

Joseph Clement (13 June 1779 – 28 February 1844) was a British engineer and industrialist, chiefly remembered as the maker of Charles Babbage's first difference engine, between 1824 and 1833.

Biography

Early life

Joseph Clement was born on ...

who had been commissioned by Babbage to manufacture the difference engine. This included investigating the ownership of intellectual property, tooling and piece-parts of the difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. It was designed in the 1820s, and was created by Charles Babbage. The name ''difference engine'' is derived from the method of finite differen ...

.

Bryan Donkin retired from an active role in the business in 1846 at the age of 78. His sons John, Bryan and Thomas continued the business.

In 1857 the British government authorised the sum of £1,200 (equivalent to £ in ) for a full-scale difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. It was designed in the 1820s, and was created by Charles Babbage. The name ''difference engine'' is derived from the method of finite differen ...

with attached printing apparatus based on the design of Per Georg Scheutz

Pehr (Per) Georg Scheutz (23 September 1785 – 22 May 1873) was a Swedish lawyer, translator, and inventor, who is now best known for his pioneering work in computer technology.

Life

Scheutz studied law at Lund University, graduating in 1805. He ...

and his son Edvard to be constructed by Donkin's company, which had acquired a reputation for building machines for the colour printing of banknotes and stamps. Costs overran and the company delivered the machine in July 1859, several weeks past the deadline, incurring a loss of £615 (equivalent to £ in ).

Despite the engine's printing unit working badly, the Royal Society and the Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the astronomer royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the astronomer royal for Scotland dating from 1834. The Astro ...

were generally positive when they inspected it on 30 August 1859, expressing their satisfaction at its construction. Donkin was unhappy that he had lost so much money on the project, which he attributed to the engine's unexpected intricacy and the fact that he had very little to base his original cost estimate on, Edvard Scheutz having given him very little information. In addition, costly machine tools had had to be made specially to make the engine's components and many alterations had been introduced along the way.

The machine was used by William Farr

William Farr Order of the Bath, CB (30 November 1807 – 14 April 1883) was a British epidemiologist, regarded as one of the founders of medical statistics.

Early life

William Farr was born in Kenley, Shropshire, to poor parents. He was effec ...

at the General Register Office

General Register Office or General Registry Office (GRO) is the name given to the civil registry in the United Kingdom, many other Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth nations and Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The GRO is the government agency r ...

to compute life table

In actuarial science and demography, a life table (also called a mortality table or actuarial table) is a table which shows, for each age, the probability that a person of that age will die before their next birthday ("probability of death"). In ...

s, which were published in 1864. It operated on 15-digit numbers and 4th-order differences, and produced printed output just as Charles Babbage had envisaged. This machine is now in the London Science Museum.

Civil engineering

Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham, Kent, Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham, Kent, Gillingham; at its most extens ...

. In 1825–27 Donkin supplied pumps for removing water from the tunnel and also workmen for modifying the tunnelling shield; at one time it was even suggested that he replace Brunel as engineer.

In 1826 he constructed a model of a landing stage proposed by Brunel for use at Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

.

Donkin's works regularly supplied machinery for use in civil engineering projects, including dredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing d ...

machines for the Caledonian Canal

The Caledonian Canal connects the Scottish east coast at Inverness with the west coast at Corpach near Fort William in Scotland. The canal was constructed in the early nineteenth century by Scottish engineer Thomas Telford.

Route

The can ...

in 1816, the Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n government in 1817, the Göta Canal

The Göta Canal () is a Swedish canal constructed in the early 19th century.

The canal is long, of which were dug or blasted, with a width varying between and a maximum depth of about .Uno Svedin, Britt Hägerhäll Aniansson, ''Sustainab ...

(Sweden) in 1821, and the Calder and Hebble Navigation in 1824. Stationary steam engines were also supplied for use in the construction of the locks on the Caledonian Canal.

As an eminent engineer, Donkin was often consulted on civil engineering matters. He supported Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford (9 August 1757 – 2 September 1834) was a Scottish civil engineer. After establishing himself as an engineer of road and canal projects in Shropshire, he designed numerous infrastructure projects in his native Scotland, as well ...

's 1814 proposals for a massive suspension bridge

A suspension bridge is a type of bridge in which the deck (bridge), deck is hung below suspension wire rope, cables on vertical suspenders. The first modern examples of this type of bridge were built in the early 1800s. Simple suspension bridg ...

at Runcorn

Runcorn is an industrial town and Runcorn Docks, cargo port in the Borough of Halton, Cheshire, England. Runcorn is on the south bank of the River Mersey, where the estuary narrows to form the Runcorn Gap. It is upstream from the port of Live ...

, and in 1821 reported along with Henry Maudslay

Henry Maudslay ( pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was an English machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology. His inventions were a ...

on an iron bridge erected by Ralph Dodd at Springfield, Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Colchester and Southend-on-Sea. It is located north-east of London ...

. Thomas Telford employed Donkin in his survey of rivers in the London area for the Water Supply report, completed shortly before Telford's death.

Other work

In 1820 Donkin worked with Sir William Congreve on preventing the forgery of excise stamps, using a method of two-colour printing with compound printing plates. Working with his partner John Wilks, he produced a machine which was used for the Excise and Stamp Office and also for theEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

at Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

. This 'Rose Engine' is now at the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

.

By 1847, Donkin's company had designed its first products for the emerging gas industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The largest volume products o ...

. The name Donkin has since become a generic name for certain gas valves and Bryan Donkin RMG Gas Controls Limited remains a going concern

A going concern is an accounting term for a business that is assumed will meet its financial obligations when they become due. It functions without the threat of liquidation for the foreseeable future, which is usually regarded as at least the n ...

in Europe. AVK and Howden Blowers also continue manufacture of Bryan Donkin equipment.

Among Donkin's other inventions were a screw-cutting and dividing machine; an instrument to measure the velocity of rotating machinery; and an engine to count the rotations of a machine. The last two received the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

Prize medal.

Death

Donkin died at home in the New Kent Road, London, on 27 February 1855. He was buried in a vault in

Donkin died at home in the New Kent Road, London, on 27 February 1855. He was buried in a vault in Nunhead Cemetery

Nunhead Cemetery is one of the Magnificent Seven cemeteries in London, England. It is perhaps the least famous and celebrated of them. The cemetery is located in Nunhead in the London Borough of Southwark and was originally known as All Saint ...

. His wife, Mary, died on 27 August 1858 and was buried in the same vault, as were other family members at later dates.

Institutions

In 1805, with John Hall and others, he formed the Society of Master Millwrights, acting as its treasurer. He was a member of theSociety of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, commonly known as the Royal Society of Arts (RSA), is a learned society that champions innovation and progress across a multitude of sectors by fostering creativity, s ...

, becoming a vice-president and chairman of the Committee of Mechanics.

He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1838.

Donkin was one of the originators and a vice-president of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a Charitable organization, charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters ar ...

, which was founded by Henry Robinson Palmer

Henry Robinson Palmer (1795–1844) was a British civil engineer who designed the world's second monorail and the first elevated railway. He is also credited as the inventor of corrugated metal roofing, which is one of the world's major buildi ...

, one of his pupils. He also helped the institution to obtain its royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

in 1828, advancing 100 guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

s towards the costs.

Donkin was elected a member of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers in 1835 and served as its president in 1843.Watson, Garth (1989), ''The Smeatonians: Society of Civil Engineers'', London: Thomas Telford,

He was a founder member of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) is a learned society and charitable organisation, charity that encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, planetary science, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. Its ...

and served on its council.

Notes

References

* * * * ''Chronicle of Britain'' * GIS/V12:2006 Gas Industry Standard Specification for Sealant replacement for valves operating up to and including 2 barBritannica article on Donkin

* "Bryan Donkin: The Very Civil Engineer 1768 - 1855" Maureen Greenland and Russ Day, Phillimore Book Publishing, 2016, , 9780993468018

External links

The Bryan Donkin Archive Trust

seeks to ensure that the artefacts of the company are preserved and to educate everyone interested about Bryan Donkin.

AVK

Howden Blowers and Compressors

{{DEFAULTSORT:Donkin, Bryan English inventors English civil engineers People of the Industrial Revolution 1768 births 1855 deaths Fellows of the Royal Society Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers People from Northumberland