Broadside ironclad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An ironclad was a steam-propelled

An ironclad was a steam-propelled

The era of the wooden steam ship-of-the-line was brief, because of new, more powerful naval guns. In the 1820s and 1830s, warships began to mount increasingly heavy guns, replacing 18- and 24-pounder guns with 32-pounders on sailing ships-of-the-line and introducing 68-pounders on steamers. Then, the first

The era of the wooden steam ship-of-the-line was brief, because of new, more powerful naval guns. In the 1820s and 1830s, warships began to mount increasingly heavy guns, replacing 18- and 24-pounder guns with 32-pounders on sailing ships-of-the-line and introducing 68-pounders on steamers. Then, the first

The use of

The use of

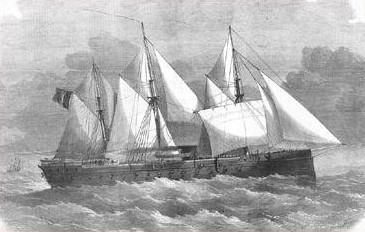

By the end of the 1850s it was clear that France was unable to match British building of steam warships, and to regain the strategic initiative a dramatic change was required. The result was the first ocean-going ironclad, , begun in 1857 and launched in 1859. ''Gloire''s wooden hull was modelled on that of a steam ship of the line, reduced to one deck, and sheathed in iron plates thick. She was propelled by a steam engine, driving a single

By the end of the 1850s it was clear that France was unable to match British building of steam warships, and to regain the strategic initiative a dramatic change was required. The result was the first ocean-going ironclad, , begun in 1857 and launched in 1859. ''Gloire''s wooden hull was modelled on that of a steam ship of the line, reduced to one deck, and sheathed in iron plates thick. She was propelled by a steam engine, driving a single  The Royal Navy had not been keen to sacrifice its advantage in steam ships of the line, but was determined that the first British ironclad would outmatch the French ships in every respect, particularly speed. A fast ship would have the advantage of being able to choose a range of engagement that could make her invulnerable to enemy fire. The British specification was more a large, powerful

The Royal Navy had not been keen to sacrifice its advantage in steam ships of the line, but was determined that the first British ironclad would outmatch the French ships in every respect, particularly speed. A fast ship would have the advantage of being able to choose a range of engagement that could make her invulnerable to enemy fire. The British specification was more a large, powerful

The first fleet battle, and the first ocean battle, involving ironclad warships was the Battle of Lissa in 1866. Waged between the Austrian and

The first fleet battle, and the first ocean battle, involving ironclad warships was the Battle of Lissa in 1866. Waged between the Austrian and

From the 1860s to the 1880s many naval designers believed that the

From the 1860s to the 1880s many naval designers believed that the

The armament of ironclads tended to become concentrated in a small number of powerful guns capable of penetrating the armor of enemy ships at range;

The armament of ironclads tended to become concentrated in a small number of powerful guns capable of penetrating the armor of enemy ships at range;

The first British, French and Russian ironclads, in a logical development of warship design from the long preceding era of wooden

The first British, French and Russian ironclads, in a logical development of warship design from the long preceding era of wooden

There were two main design alternatives to the broadside. In one design, the guns were placed in an armored casemate amidships: this arrangement was called the 'box-battery' or 'center-battery'. In the other, the guns could be placed on a rotating platform to give them a broad field of fire; when fully armored, this arrangement was called a

There were two main design alternatives to the broadside. In one design, the guns were placed in an armored casemate amidships: this arrangement was called the 'box-battery' or 'center-battery'. In the other, the guns could be placed on a rotating platform to give them a broad field of fire; when fully armored, this arrangement was called a

The first ironclads were built on wooden or iron hulls, and protected by wrought iron armor backed by thick wooden planking. Ironclads were still being built with wooden hulls into the 1870s.

The first ironclads were built on wooden or iron hulls, and protected by wrought iron armor backed by thick wooden planking. Ironclads were still being built with wooden hulls into the 1870s.

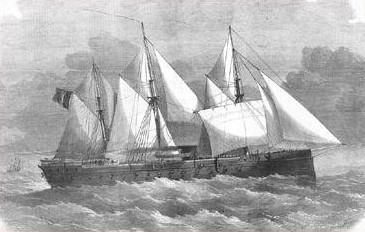

The first ocean-going ironclads carried masts and sails like their wooden predecessors, and these features were only gradually abandoned. Early steam engines were inefficient; the wooden steam fleet of the Royal Navy could only carry "5 to 9 days coal",Beeler, p. 54 and the situation was similar with the early ironclads. ''Warrior'' also illustrates two design features which aided hybrid propulsion; she had retractable screws to reduce drag while under sail (though in practice the steam engine was run at a low throttle), and a telescopic funnel which could be folded down to the deck level.

The first ocean-going ironclads carried masts and sails like their wooden predecessors, and these features were only gradually abandoned. Early steam engines were inefficient; the wooden steam fleet of the Royal Navy could only carry "5 to 9 days coal",Beeler, p. 54 and the situation was similar with the early ironclads. ''Warrior'' also illustrates two design features which aided hybrid propulsion; she had retractable screws to reduce drag while under sail (though in practice the steam engine was run at a low throttle), and a telescopic funnel which could be folded down to the deck level.

Ships designed for coastal warfare, like the floating batteries of the Crimea, or and her sisters, dispensed with masts from the beginning. The British , started in 1869, was the first large, ocean-going ironclad to dispense with masts. Her principal role was for combat in the English Channel and other European waters; while her coal supplies gave her enough range to cross the Atlantic, she would have had little endurance on the other side of the ocean. The ''Devastation'' and the similar ships commissioned by the British and Russian navies in the 1870s were the exception rather than the rule. Most ironclads of the 1870s retained masts, and only the Italian navy, which during that decade was focused on short-range operations in the Adriatic, built consistently mastless ironclads.

During the 1860s, steam engines improved with the adoption of double-expansion steam engines, which used 30–40% less coal than earlier models. The Royal Navy decided to switch to the double-expansion engine in 1871, and by 1875 they were widespread. However, this development alone was not enough to herald the end of the mast. Whether this was due to a conservative desire to retain sails, or was a rational response to the operational and strategic situation, is a matter of debate. A steam-only fleet would require a network of coaling stations worldwide, which would need to be fortified at great expense to stop them falling into enemy hands. Just as significantly, because of unsolved problems with the technology of the boilers which provided steam for the engines, the performance of double-expansion engines was rarely as good in practice as it was in theory.

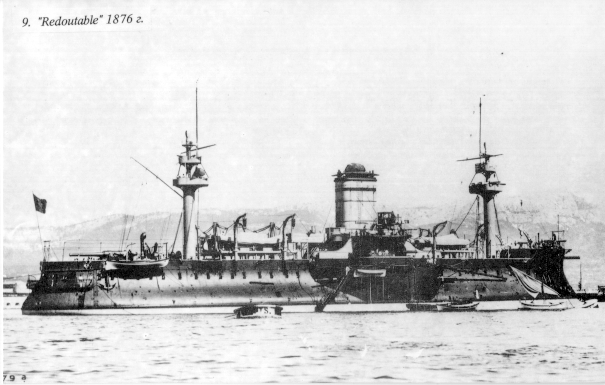

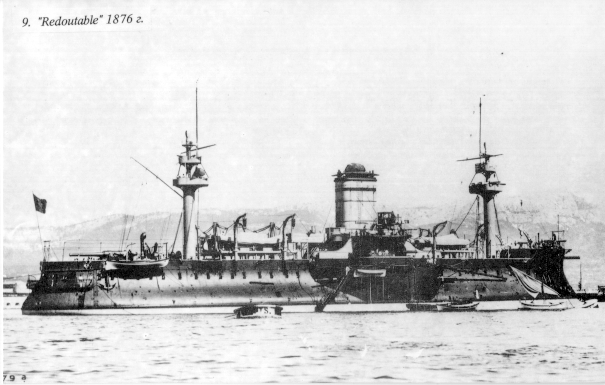

During the 1870s the distinction grew between 'first-class ironclads' or 'battleships' on the one hand, and 'cruising ironclads' designed for long-range work on the other. The demands on first-class ironclads for very heavy armor and armament meant increasing displacement, which reduced speed under sail; and the fashion for turrets and barbettes made a sailing rig increasingly inconvenient. , launched in 1876 but not commissioned until 1881, was the last British battleship to carry masts, and these were widely seen as a mistake. The start of the 1880s saw the end of sailing rig on ironclad battleships.

Sails persisted on 'cruising ironclads' for much longer. During the 1860s, the French navy had produced the and es as small, long-range ironclads as overseas cruisers and the British had responded with ships like of 1870. The Russian ship , laid down in 1870 and completed in 1875, was a model of a fast, long-range ironclad which was likely to be able to outrun and outfight ships like ''Swiftsure''. Even the later , often described as the first British armored cruiser, would have been too slow to outrun ''General-Admiral''. While ''Shannon'' was the last British ship with a retractable propeller, later armored cruisers of the 1870s retained sailing rig, sacrificing speed under steam in consequence. It took until 1881 for the Royal Navy to lay down a long-range armored warship capable of catching enemy commerce raiders, , which was completed in 1888. While sailing rigs were obsolescent for all purposes by the end of the 1880s, rigged ships were in service until the early years of the 20th century.

The final evolution of ironclad propulsion was the adoption of the triple-expansion steam engine, a further refinement which was first adopted in , laid down in 1885 and commissioned in 1891. Many ships also used a forced draught to get additional power from their engines, and this system was widely used until the introduction of the

Ships designed for coastal warfare, like the floating batteries of the Crimea, or and her sisters, dispensed with masts from the beginning. The British , started in 1869, was the first large, ocean-going ironclad to dispense with masts. Her principal role was for combat in the English Channel and other European waters; while her coal supplies gave her enough range to cross the Atlantic, she would have had little endurance on the other side of the ocean. The ''Devastation'' and the similar ships commissioned by the British and Russian navies in the 1870s were the exception rather than the rule. Most ironclads of the 1870s retained masts, and only the Italian navy, which during that decade was focused on short-range operations in the Adriatic, built consistently mastless ironclads.

During the 1860s, steam engines improved with the adoption of double-expansion steam engines, which used 30–40% less coal than earlier models. The Royal Navy decided to switch to the double-expansion engine in 1871, and by 1875 they were widespread. However, this development alone was not enough to herald the end of the mast. Whether this was due to a conservative desire to retain sails, or was a rational response to the operational and strategic situation, is a matter of debate. A steam-only fleet would require a network of coaling stations worldwide, which would need to be fortified at great expense to stop them falling into enemy hands. Just as significantly, because of unsolved problems with the technology of the boilers which provided steam for the engines, the performance of double-expansion engines was rarely as good in practice as it was in theory.

During the 1870s the distinction grew between 'first-class ironclads' or 'battleships' on the one hand, and 'cruising ironclads' designed for long-range work on the other. The demands on first-class ironclads for very heavy armor and armament meant increasing displacement, which reduced speed under sail; and the fashion for turrets and barbettes made a sailing rig increasingly inconvenient. , launched in 1876 but not commissioned until 1881, was the last British battleship to carry masts, and these were widely seen as a mistake. The start of the 1880s saw the end of sailing rig on ironclad battleships.

Sails persisted on 'cruising ironclads' for much longer. During the 1860s, the French navy had produced the and es as small, long-range ironclads as overseas cruisers and the British had responded with ships like of 1870. The Russian ship , laid down in 1870 and completed in 1875, was a model of a fast, long-range ironclad which was likely to be able to outrun and outfight ships like ''Swiftsure''. Even the later , often described as the first British armored cruiser, would have been too slow to outrun ''General-Admiral''. While ''Shannon'' was the last British ship with a retractable propeller, later armored cruisers of the 1870s retained sailing rig, sacrificing speed under steam in consequence. It took until 1881 for the Royal Navy to lay down a long-range armored warship capable of catching enemy commerce raiders, , which was completed in 1888. While sailing rigs were obsolescent for all purposes by the end of the 1880s, rigged ships were in service until the early years of the 20th century.

The final evolution of ironclad propulsion was the adoption of the triple-expansion steam engine, a further refinement which was first adopted in , laid down in 1885 and commissioned in 1891. Many ships also used a forced draught to get additional power from their engines, and this system was widely used until the introduction of the

The US Navy ended the Civil War with about fifty

The US Navy ended the Civil War with about fifty  Ironclads were widely used in South America. Both sides used ironclads in the

Ironclads were widely used in South America. Both sides used ironclads in the  Ironclads were also used from the inception of the

Ironclads were also used from the inception of the

Northrop Grumman Employees Reconstruct History with USS Monitor Replica

Retrieved 2007-05-21. * * * Reed, Edward J. (1869). ''Our Ironclad Ships, their Qualities, Performance and Cost''. John Murray. * * * * Sandler, Stanley (1979). ''Emergence of the Modern Capital Ship''. Newark, Delaware: Associated University Presses. . . * * Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). ''Naval Warfare 1815–1914''. London: Routledge. . * * *

The first ironclads 1859–1872, engravings

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20070927185849/http://www.bruzelius.info/nautica/Ships/Naval_Science%281874%29_p1.html Circular Iron-Clads in the Imperial Russian Navy {{DEFAULTSORT:Ironclad Warship Ship types Naval armour

An ironclad was a steam-propelled

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as b ...

protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The first ironclad battleship, , was launched by the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

in November 1859, narrowly preempting the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. However, Britain built the first completely iron-hulled warships.

Ironclads were first used in warfare in 1862 during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, when they operated against wooden ships, and against each other at the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

The battle was fought over two days, March 8 and 9, 1862, in Hampton ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. Their performance demonstrated that the ironclad had replaced the unarmored ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactics in the Age of Sail, naval tactic known as the line of battl ...

as the most powerful warship afloat. Ironclad gunboats became very successful in the American Civil War.

Ironclads were designed for several uses, including as high-seas battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s, long-range cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

s, and coastal defense ships. Rapid development of warship design in the late 19th century transformed the ironclad from a wooden-hulled vessel that carried sails to supplement its steam engines into the steel-built, turreted battleships, and cruisers familiar in the 20th century. This change was pushed forward by the development of heavier naval guns, more sophisticated steam engines, and advances in ferrous metallurgy

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

that made steel shipbuilding possible.

The quick pace of change meant that many ships were obsolete almost as soon as they were finished and that naval tactics were in a state of flux. Many ironclads were built to make use of the naval ram

A ram on the bow of ''Olympias'', a modern reconstruction of an ancient Athenian trireme

A naval ram is a weapon fitted to varied types of ships, dating back to antiquity. The weapon comprised an underwater prolongation of the bow of the sh ...

, the torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

, or sometimes both (as in the case with smaller ships and later torpedo boats), which several naval designers considered the important weapons of naval combat. There is no clear end to the ironclad period, but toward the end of the 1890s, the term ''ironclad'' dropped out of use. New ships were increasingly constructed to a standard pattern and designated as battleships or armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

s.

Development

The ironclad became technically feasible and tactically necessary because of developments in shipbuilding in the first half of the 19th century. According to naval historian J. Richard Hill: "The (ironclad) had three chief characteristics: a metal-skinned hull, steam propulsion and a main armament of guns capable of firing explosive shells. It is only when all three characteristics are present that a fighting ship can properly be called an ironclad."Hill, p. 17 Each of these developments was introduced separately in the decade before the first ironclads.Steam propulsion

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, fleets had relied on two types of major warship, theship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactics in the Age of Sail, naval tactic known as the line of battl ...

and the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

. The first major change to these types was the introduction of steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be transf ...

for propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived from ...

. While paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine driving paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, whereby the first uses were wh ...

warships had been used from the 1830s onward, steam propulsion only became suitable for major warships after the adoption of the screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

in the 1840s.Lambert, "The Screw Propeller Warship", pp. 30–44

Steam-powered screw frigates were built in the mid-1840s, and at the end of the decade the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

introduced steam power to its line of battle

The line of battle or the battle line is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships (known as ships of the line) forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for date ...

. Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

's ambition to gain greater influence in Europe required a sustained challenge to the British at sea.Hill, p. 25 The first purpose-built steam battleship was the 90-gun in 1850. ''Napoléon'' was armed as a conventional ship-of-the-line, but her steam engines could give her a speed of , regardless of the wind conditions: a potentially decisive advantage in a naval engagement.

The introduction of the steam ship-of-the-line led to a building competition between France and Britain. Eight sister ships to ''Napoléon'' were built in France over a period of ten years, but the United Kingdom soon managed to take the lead in production. Altogether, France built ten new wooden steam battleships and converted 28 from older ships of the line, while the United Kingdom built 18 and converted 41.

Explosive shells

The era of the wooden steam ship-of-the-line was brief, because of new, more powerful naval guns. In the 1820s and 1830s, warships began to mount increasingly heavy guns, replacing 18- and 24-pounder guns with 32-pounders on sailing ships-of-the-line and introducing 68-pounders on steamers. Then, the first

The era of the wooden steam ship-of-the-line was brief, because of new, more powerful naval guns. In the 1820s and 1830s, warships began to mount increasingly heavy guns, replacing 18- and 24-pounder guns with 32-pounders on sailing ships-of-the-line and introducing 68-pounders on steamers. Then, the first shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard outer layer of a marine ani ...

guns firing explosive shells were introduced following their development by the French Général Henri-Joseph Paixhans

Henri-Joseph Paixhans (; January 22, 1783, Metz – August 22, 1854, Jouy-aux-Arches) was a French artillery officer of the beginning of the 19th century.

Henri-Joseph Paixhans graduated from the École Polytechnique. He fought in the Napoleonic ...

. By the 1840s they were part of the standard armament for naval powers including the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

, Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

and United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

.

It is often held that the power of explosive shells to smash wooden hulls, as demonstrated by the Russian destruction of an Ottoman squadron at the Battle of Sinop

The Battle of Sinop, or the Battle of Sinope, was a naval battle that took place on 30 November 1853 between Imperial Russia and the Ottoman Empire during the opening phase of the Crimean War (1853–1856). It took place at Sinop, Turkey, Sinop ...

, spelled the end of the wooden-hulled warship. The more practical threat to wooden ships was from conventional cannon firing red-hot shot, which could lodge in the hull and cause a fire or ammunition explosion. Some navies even experimented with hollow shot filled with molten metal for extra incendiary power.Lambert, ''Battleships in Transition'', pp. 94–95

Iron armor

The use of

The use of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

instead of wood as the primary material of ships' hulls began in the 1830s; the first "warship" with an iron hull was the gunboat ''Nemesis'', built by Jonathan Laird of Birkenhead for the East India Company in 1839. There followed, also from Laird, the first full-sized warship with a metal hull, the 1842 steam frigate '' Guadalupe'' for the Mexican Navy

The Mexican Navy () is one of the components of the Mexican Armed Forces. The Secretariat of the Navy is in charge of administration of the navy. The commander of the navy is the Secretary of the Navy, who is both a cabinet minister and a career ...

.Sandler, ''Battleships: An Illustrated History of Their Impact'', p. 20 The latter ship performed well during the Naval Battle of Campeche, with her captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

reporting that he thought that there were fewer iron splinters from ''Guadalupe''s hull than from a wooden hull.

Encouraged by the positive reports of the iron hulls of those ships in combat, the Admiralty ordered a series of experiments to evaluate what happened when thin iron hulls were struck by projectiles, both solid shot and hollow shells, beginning in 1845 and lasting through 1851. Critics like Lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Sir Howard Douglas

General Sir Howard Douglas, 3rd Baronet, (23 January 1776 – 9 November 1861) was a British Army officer born in Gosport, England, the younger son of Admiral Sir Charles Douglas, and a descendant of the Earls of Morton. He was an English ...

believed that the splinters from the hull were even more dangerous than those from wooden hulls and the tests partially confirmed this belief. What was ignored was that of wood backing the iron would stop most of the splinters from penetrating and that relatively thin plates of iron backed by the same thickness of wood would generally cause shells to split open and fail to detonate.

The early experimental results seemed to support the critics and party politics came into play as the Whig First Russell ministry replaced the Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

Second Peel Ministry

The second Peel ministry was formed by Sir Robert Peel in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1841.

History

Peel came to power for a second time after the Conservative victory in the General Election caused the Whig government ...

in 1846. The new administration sided with the critics and ordered that the four iron-hulled propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s ordered by the Tories be converted into troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable to land troops directly on shore, typic ...

s. No iron warships would be ordered until the beginning of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

in 1854.

Following the demonstration of the power of explosive shells against wooden ships at the Battle of Sinop

The Battle of Sinop, or the Battle of Sinope, was a naval battle that took place on 30 November 1853 between Imperial Russia and the Ottoman Empire during the opening phase of the Crimean War (1853–1856). It took place at Sinop, Turkey, Sinop ...

, and fearing that his own ships would be vulnerable to the Paixhans guns of Russian fortifications in the Crimean War, Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

ordered the development of light-draft floating batteries, equipped with heavy guns and protected by heavy armor. Experiments made during the first half of 1854 proved highly satisfactory, and on 17 July 1854, the French communicated to the British Government that a solution had been found to make gun-proof vessels and that plans would be communicated. After tests in September 1854, the British Admiralty agreed to build five armored floating batteries on the French plans.

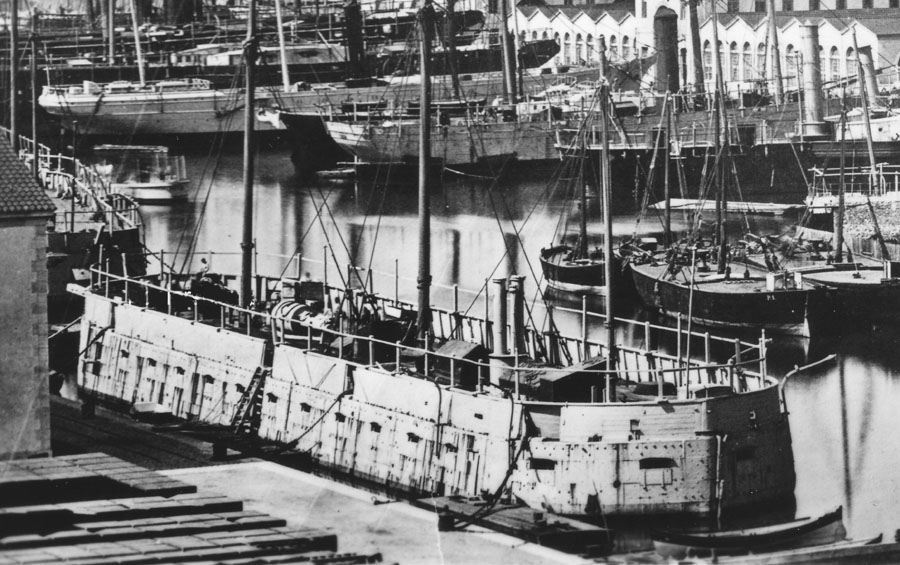

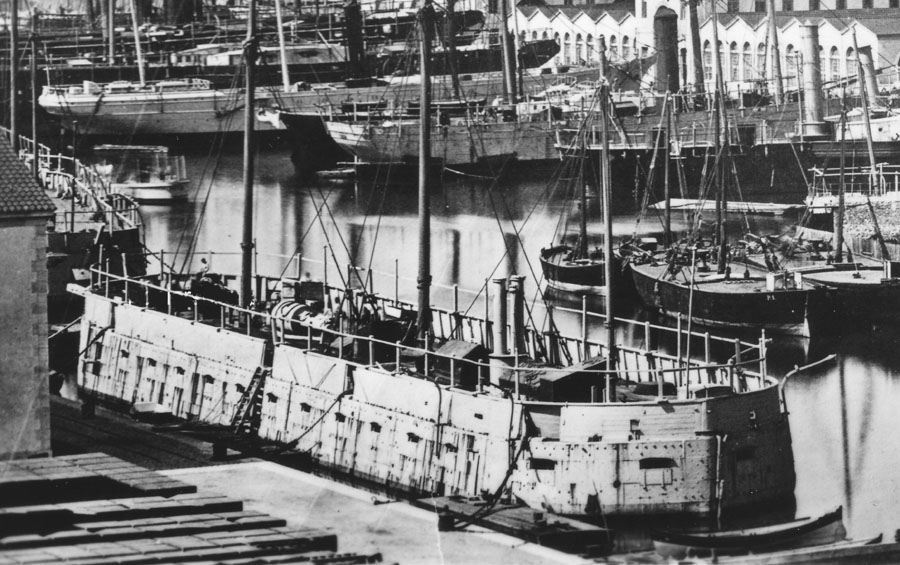

The French floating batteries were deployed in 1855 as a supplement to the wooden steam battle fleet in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. The role of the battery was to assist unarmored mortar and gunboats bombarding shore fortifications. The French used three of their ironclad batteries (''Lave'', ''Tonnante'' and ''Dévastation'') in 1855 against the defenses at the Battle of Kinburn on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

, where they were effective against Russian shore defences. They would later be used again during the Italian war in the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

in 1859. The British floating batteries and arrived too late to participate to the action at Kinburn.Baxter, p. 82 The British planned to use theirs in the Baltic Sea against the well-fortified Russian naval base at Kronstadt.Lambert, "Iron Hulls and Armour Plate", pp. 47–55

The batteries have a claim to the title of the first ironclad warships but they were capable of only under their own power: they operated under their own power at the Battle of Kinburn,Baxter, p. 84 but had to be towed for long-range transit. They were also arguably marginal to the work of the navy. The brief success of the floating ironclad batteries convinced France to begin work on armored warships for their battlefleet.

Early ironclad ships and battles

By the end of the 1850s it was clear that France was unable to match British building of steam warships, and to regain the strategic initiative a dramatic change was required. The result was the first ocean-going ironclad, , begun in 1857 and launched in 1859. ''Gloire''s wooden hull was modelled on that of a steam ship of the line, reduced to one deck, and sheathed in iron plates thick. She was propelled by a steam engine, driving a single

By the end of the 1850s it was clear that France was unable to match British building of steam warships, and to regain the strategic initiative a dramatic change was required. The result was the first ocean-going ironclad, , begun in 1857 and launched in 1859. ''Gloire''s wooden hull was modelled on that of a steam ship of the line, reduced to one deck, and sheathed in iron plates thick. She was propelled by a steam engine, driving a single screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

for a speed of . She was armed with thirty-six rifled guns. France proceeded to construct 16 ironclad warships, including two sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

s to ''Gloire'', and the only two-decked broadside ironclads ever built, and .Sondhaus, pp. 73–74

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

than a ship-of-the-line. The requirement for speed meant a very long vessel, which had to be built from iron. The result was the construction of two s; and . The ships had a successful design, though there were necessarily compromises between 'sea-keeping', strategic range and armor protection. Their weapons were more effective than those of ''Gloire'', and with the largest set of steam engines yet fitted to a ship, they could steam at 14.3 knots (26.5 km/h). Yet the ''Gloire'' and her sisters had full iron-armor protection along the waterline and the battery itself.

The British ''Warrior'' and ''Black Prince'' (but also the smaller ''Defence'' and ''Resistance'') were obliged to concentrate their armor in a central "citadel" or "armoured box", leaving many main deck guns and the fore and aft sections of the vessel unprotected. The use of iron in the construction of ''Warrior ''also came with some drawbacks; iron hulls required more regular and intensive repairs than wooden hulls, and iron was more susceptible to fouling by marine life.

By 1862, navies across Europe had adopted ironclads. Britain and France each had sixteen either completed or under construction, though the British vessels were larger. Austria, Italy, Russia, and Spain were also building ironclads. However, the first battles using the new ironclad ships took place during the American Civil War, between Union and Confederate ships in 1862. These were markedly different from the broadside-firing, masted designs of ''Gloire'' and ''Warrior''. The clash of the Italian and Austrian fleets at the Battle of Lissa (1866), also had an important influence on the development of ironclad design.

First battles between ironclads: the U.S. Civil War

The first use of ironclads in combat came in the U.S. Civil War. The U.S. Navy at the time the war broke out had no ironclads, its most powerful ships being six unarmored steam-powered frigates. Since the bulk of the Navy remained loyal to the Union, the Confederacy sought to gain advantage in the naval conflict by acquiring modern armored ships. In May 1861, the Confederate Congress appropriated $2 million dollars for the purchase of ironclads from overseas, and in July and August 1861 the Confederacy started work on construction and converting wooden ships.Still, "The American Civil War", pp. 70–71 On 12 October 1861, became the first ironclad to enter combat, when she fought Union warships on the Mississippi during the Battle of the Head of Passes. She had been converted from a commercial vessel in New Orleans for river and coastal fighting. In February 1862, the larger joined the Confederate Navy, having been rebuilt atNorfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

. Constructed on the hull of , ''Virginia'' originally was a conventional warship made of wood, but she was converted into an iron-covered casemate ironclad

The casemate ironclad was a type of iron or iron-armored gunboat briefly used in the American Civil War by both the Confederate States Navy and the Union Navy. Unlike a monitor-type ironclad which carried its armament encased in a separate ...

gunship, when she entered the Confederate Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

. By this time, the Union had completed seven ironclad gunboats of the , and was about to complete , an innovative design proposed by the Swedish inventor John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American engineer and inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive Novelty (lo ...

. The Union was also building a large armored frigate, , and the smaller .

The first battle between ironclads happened on 9 March 1862, as the armored ''Monitor'' was deployed to protect the Union's wooden fleet from the ironclad ram ''Virginia'' and other Confederate warships. In this engagement, the second day of the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Merrimack'' or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

The battle was fought over two days, March 8 and 9, 1862, in Hampton ...

, the two ironclads tried to ram one another while shells bounced off their armor. The battle attracted attention worldwide, making it clear that the wooden warship was now out of date, with the ironclads destroying them easily.

The Civil War saw more ironclads built by both sides, and they played an increasing role in the naval war alongside the unarmored warships, commerce raiders and blockade runners. The Union built a large fleet of fifty monitors modeled on their namesake. The Confederacy built ships designed as smaller versions of ''Virginia'', many of which saw action, but their attempts to buy ironclads overseas were frustrated as European nations confiscated ships being built for the Confederacy – especially in Russia, the only country to openly support the Union through the war. Only CSS ''Stonewall'' was completed, and she arrived in Cuban waters just in time for the end of the war.

Through the remainder of the war, ironclads saw action in the Union's attacks on Confederate ports. Seven Union monitors, including , as well as two other ironclads, the armored frigate ''New Ironsides'' and a light-draft , participated in the failed attack on Charleston; one was sunk. Two small ironclads, and participated in the defense of the harbor. For the later attack at Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. T ...

, the Union assembled four monitors as well as 11 wooden ships, facing the , the Confederacy's most powerful ironclad, and three gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s.

On the western front, the Union built a formidable force of river ironclads, beginning with several converted riverboats and then contracting engineer James Eads of St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

to build the City-class ironclads. These excellent ships were built with twin engines and a central paddle wheel, all protected by an armored casemate. They had a shallow draft, allowing them to journey up smaller tributaries, and were very well suited for river operations. Eads also produced monitors for use on the rivers, the first two of which differed from the ocean-going monitors in that they contained a paddle wheel ( and ).

The Union ironclads played an important role in the Mississippi and tributaries by providing tremendous fire upon Confederate forts, installations and vessels with relative impunity to enemy fire. They were not as heavily armored as the ocean-going monitors of the Union, but they were adequate for their intended use. More Western Flotilla Union ironclads were sunk by torpedoes (mines) than by enemy fire, and the most damaging fire for the Union ironclads was from shore installations, not Confederate vessels.

Lissa: first fleet battle

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

navies, the battle pitted combined fleets of wooden frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s and corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloo ...

s and ironclad warships on both sides in the largest naval battle between the battles of Navarino Navarino or Navarin may refer to:

Battle

* Battle of Navarino, 1827 naval battle off Navarino, Greece, now known as Pylos

Geography

* Navarino is the former name of Pylos, a Greek town on the Ionian Sea, where the 1827 battle took place

** Old Na ...

and Tsushima.Sondhaus, pp. 94–96

The Italian fleet consisted of 12 ironclads and a similar number of wooden warships, escorting transports which carried troops intending to land on the Adriatic island of Lissa. Among the Italian ironclads were seven broadside ironclad frigates, four smaller ironclads, and the newly built – a double-turreted ram. Opposing them, the Austrian navy had seven ironclad frigates.

The Austrians believed their ships to have less effective guns than their enemy, so decided to engage the Italians at close range and ram them. The Austrian fleet formed into an arrowhead formation with the ironclads in the first line, charging at the Italian ironclad squadron. In the melée which followed both sides were frustrated by the lack of damage inflicted by guns, and by the difficulty of ramming—nonetheless, the effective ramming attack being made by the Austrian flagship against the Italian attracted great attention in following years.

The superior Italian fleet lost its two ironclads, and , while the Austrian unarmored screw two-decker remarkably survived close actions with four Italian ironclads. The battle ensured the popularity of the ram as a weapon in European ironclads for many years, and the victory won by Austria established it as the predominant naval power in the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

.

The battles of the American Civil War and at Lissa were very influential on the designs and tactics of the ironclad fleets that followed. In particular, it taught a generation of naval officers the (ultimately erroneous) lesson that ramming was the best way to sink enemy ironclads.

Armament and tactics

The adoption of iron armor meant that the traditional naval armament of dozens of light cannon became useless, since their shot would bounce off an armored hull. To penetrate armor, increasingly heavy guns were mounted on ships; nevertheless, the view thatramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege engine used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus ...

was the only way to sink an ironclad became widespread. The increasing size and weight of guns also meant a movement away from the ships mounting many guns broadside, in the manner of a ship-of-the-line, towards a handful of guns in turrets for all-round fire.

Ram craze

From the 1860s to the 1880s many naval designers believed that the

From the 1860s to the 1880s many naval designers believed that the ram

Ram, ram, or RAM most commonly refers to:

* A male sheep

* Random-access memory, computer memory

* Ram Trucks, US, since 2009

** List of vehicles named Dodge Ram, trucks and vans

** Ram Pickup, produced by Ram Trucks

Ram, ram, or RAM may also ref ...

was again a vital weapon in naval warfare. With steam power freeing ships from the wind, iron construction increasing their structural strength, and armor making them invulnerable to shellfire, the ram seemed to offer the opportunity to strike a decisive blow.Brown, ''Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Design and Development, 1860–1905'', p. 22

The scant damage inflicted by the guns of ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' at Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond, and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point near whe ...

and the spectacular but lucky success of the Austrian flagship SMS ''Erzherzog Ferdinand Max'' sinking the Italian ''Re d'Italia'' at Lissa gave strength to the ramming craze. From the early 1870s to early 1880s most British naval officers thought that guns were about to be replaced as the main naval armament by the ram. Those who noted the tiny number of ships that had actually been sunk by ramming struggled to be heard.Beeler, pp. 106–107

The revival of ramming had a significant effect on naval tactics. Since the 17th century the predominant tactic of naval warfare had been the line of battle

The line of battle or the battle line is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships (known as ships of the line) forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for date ...

, where a fleet formed a long line to give it the best fire from its broadside guns. This tactic was totally unsuited to ramming, and the ram threw fleet tactics into disarray. The question of how an ironclad fleet should deploy in battle to make best use of the ram was never tested in battle, and if it had been, combat might have shown that rams could only be used against ships which were already stopped dead in the water.

The ram finally fell out of favor in the 1880s, as the same effect could be achieved with a torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

, with less vulnerability to quick-firing guns.

Development of naval guns

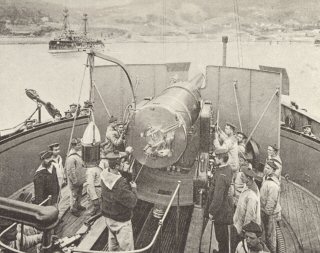

The armament of ironclads tended to become concentrated in a small number of powerful guns capable of penetrating the armor of enemy ships at range;

The armament of ironclads tended to become concentrated in a small number of powerful guns capable of penetrating the armor of enemy ships at range; calibre

In guns, particularly firearms, but not artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel bore – regardless of how or wher ...

and weight of guns increased markedly to achieve greater penetration. Throughout the ironclad era navies also grappled with the complexities of rifled versus smoothbore

A smoothbore weapon is one that has a barrel without rifling. Smoothbores range from handheld firearms to powerful tank guns and large artillery mortars. Some examples of smoothbore weapons are muskets, blunderbusses, and flintlock pistols. ...

guns and breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition from the breech end of the barrel (i.e., from the rearward, open end of the gun's barrel), as opposed to a muzzleloader, in which the user loads the ammunition from the ( muzzle ...

versus muzzle-loading

A muzzleloader is any firearm in which the user loads the projectile and the propellant charge into the muzzle end of the gun (i.e., from the forward, open end of the gun's barrel). This is distinct from the modern designs of breech-loading fire ...

.

carried a mixture of 110-pounder breech-loading rifles and more traditional 68-pounder smoothbore guns. ''Warrior'' highlighted the challenges of picking the right armament; the breech-loaders she carried, designed by Sir William Armstrong, were intended to be the next generation of heavy armament for the Royal Navy, but were shortly withdrawn from service.Beeler, p. 71

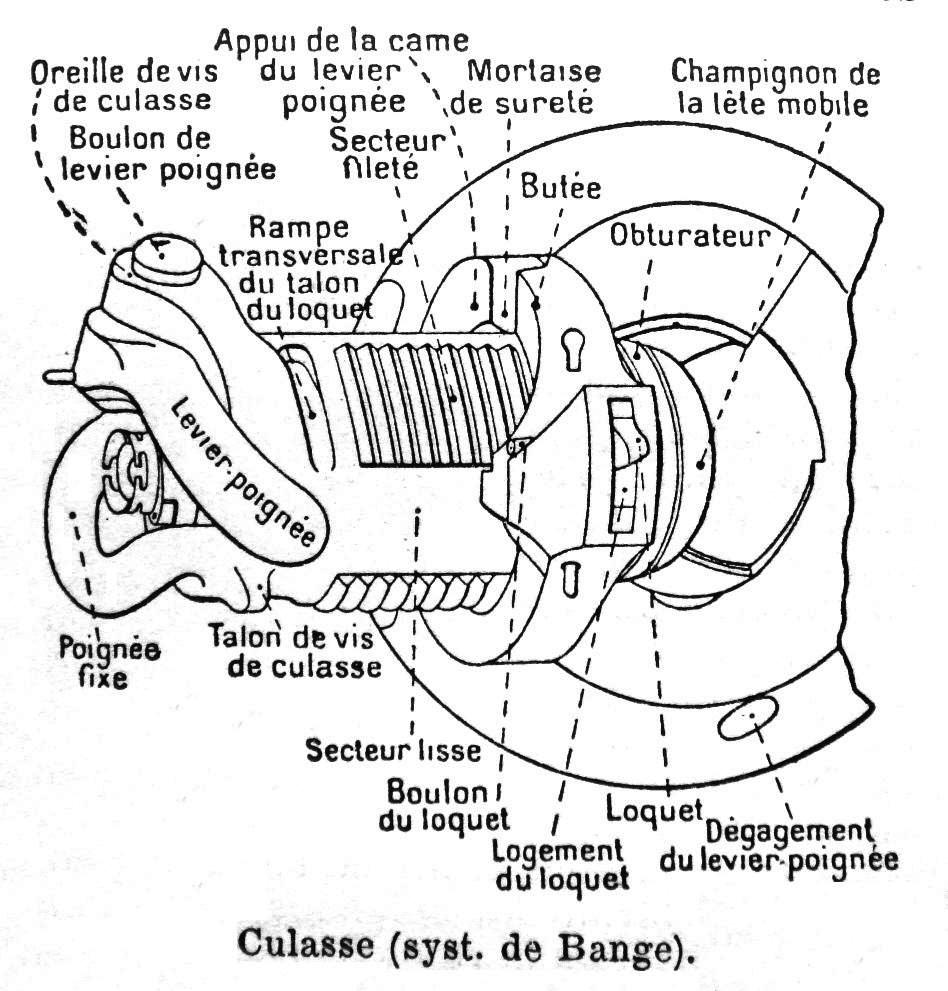

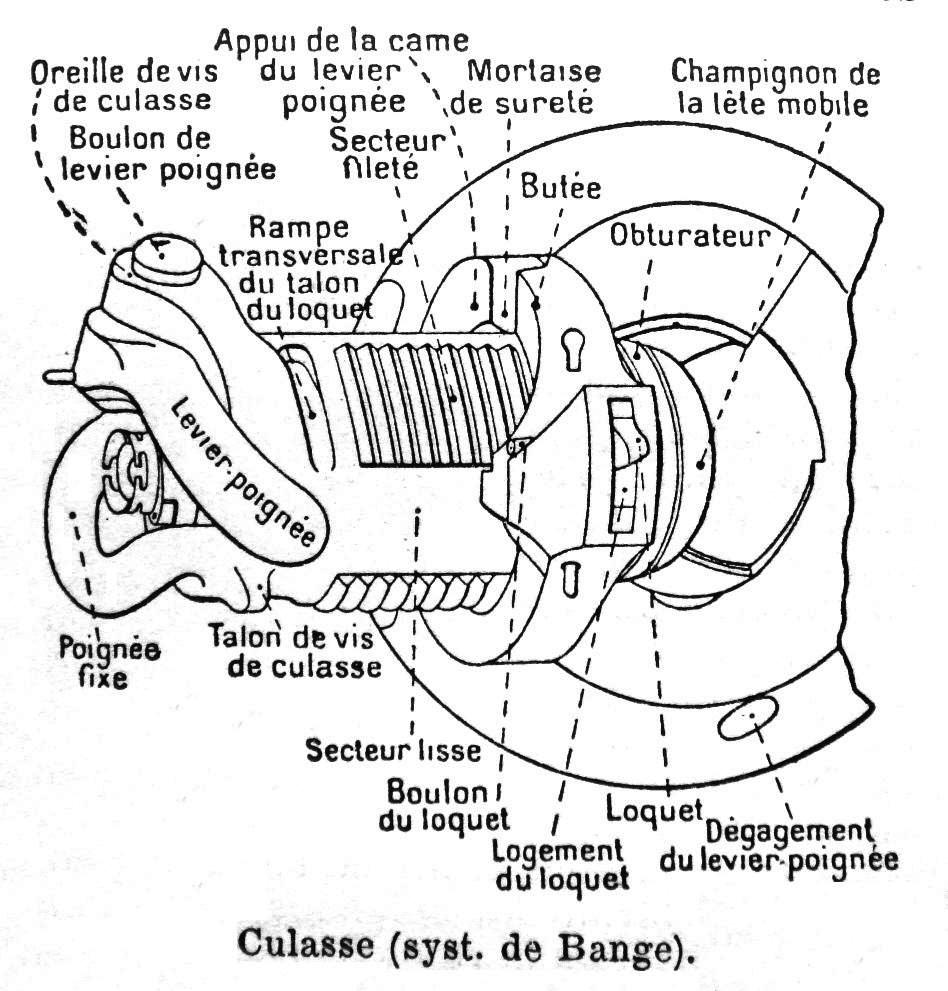

Breech-loading guns seemed to offer important advantages. A breech-loader could be reloaded without moving the gun, a lengthy process particularly if the gun then needed to be re-aimed. ''Warrior''s Armstrong guns also had the virtue of being lighter than an equivalent smoothbore and, because of their rifling, more accurate. Nonetheless, the design was rejected because of problems which plagued breech-loaders for decades.

The weakness of the breech-loader was the obvious problem of sealing the breech. All guns are powered by the explosive conversion of a solid propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicle ...

into gas. This explosion propels the shot or shell out of the front of the gun, but also imposes great stresses on the gun-barrel. If the breech—which experiences some of the greatest forces in the gun—is not entirely secure, then there is a risk that either gas will discharge through the breech or that the breech will break. This in turn reduces the muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

of the weapon and can also endanger the gun crew. ''Warrior''s Armstrong guns suffered from both problems; the shells were unable to penetrate the armor of ''Gloire'', while sometimes the screw which closed the breech flew backwards out of the gun on firing. Similar problems were experienced with the breech-loading guns which became standard in the French and German navies.

These problems influenced the British to equip ships with muzzle-loading weapons of increasing power until the 1880s. After a brief introduction of the 100-pounder or smoothbore Somerset Gun, which weighed , the Admiralty introduced 7-inch (178 mm) rifled guns, weighing . These were followed by a series of increasingly mammoth weapons—guns weighing , , , and finally , with caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, but not #As a measurement of length, artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge ( ...

increasing from 8 inches (203 mm) to 16 inches (406 mm).

The decision to retain muzzle-loaders until the 1880s has been criticized by historians. However, at least until the late 1870s, the British muzzle-loaders had superior performance in terms of both range and rate of fire than the French and Prussian breech-loaders, which suffered from the same problems as the first Armstrong guns.

From 1875 onwards, the balance between breech- and muzzle-loading changed. Captain de Bange invented a method of reliably sealing a breech, adopted by the French in 1873. Just as compellingly, the growing size of naval guns and consequently, their ammunition, made muzzle-loading much more complicated. With guns of such size there was no prospect of hauling in the gun for reloading, or even reloading by hand, and complicated hydraulic systems were required for reloading the gun outside the turret without exposing the crew to enemy fire. In 1882, the 81-ton, 16-inch guns of fired only once every 11 minutes while bombarding Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

during the Urabi Revolt

The ʻUrabi revolt, also known as the ʻUrabi Revolution (), was a nationalist uprising in the Khedivate of Egypt from 1879 to 1882. It was led by and named for Colonel Ahmed Urabi and sought to depose the khedive, Tewfik Pasha, and end Imperia ...

. The , 450 mm (17.72 inch) guns of the could each fire a round every 15 minutes.

In the Royal Navy, the switch to breech-loaders was finally made in 1879; as well as the significant advantages in terms of performance, opinion was swayed by an explosion on board caused by a gun being double-loaded, a problem which could only happen with a muzzle-loading gun.Roberts, "Warships of Steel 1879–1889", p. 98

The caliber and weight of guns could only increase so far. The larger the gun, the slower it would be to load, the greater the stresses on the ship's hull, and the less the stability of the ship. The size of the gun peaked in the 1880s, with some of the heaviest calibers of gun ever used at sea. carried two 16.25-inch (413 mm) breech-loading guns, each weighing . A few years afterwards, the Italians used 450 mm (17.72 inch) muzzle-loading guns on the ''Duilio'' class ships. One consideration which became more acute was that even from the original Armstrong models, following the Crimean War, range and hitting power far exceeded simple accuracy, especially at sea where the slightest roll or pitch of the vessel as 'floating weapons-platform' could negate the advantage of rifling. American ordnance experts accordingly preferred smoothbore monsters whose round shot could at least 'skip' along the surface of the water. Actual effective combat ranges, they had learned during the Civil War, were comparable to those in the Age of Sail—though a vessel could now be smashed to pieces in only a few rounds. Smoke and the general chaos of battle only added to the problem. As a result, many naval engagements in the 'Age of the Ironclad' were still fought at ranges within easy eyesight of their targets, and well below the maximum reach of their ships' guns.

Another method of increasing firepower was to vary the projectile fired or the nature of the propellant. Early ironclads used black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

, which expanded rapidly after combustion; this meant cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

s had relatively short barrels, to prevent the barrel itself slowing the shell. The sharpness of the black powder explosion also meant that guns were subjected to extreme stress. One important step was to press the powder into pellets, allowing a slower, more controlled explosion and a longer barrel. A further step forward was the introduction of chemically different brown powder which combusted more slowly again. It also put less stress on the insides of the barrel, allowing guns to last longer and to be manufactured to tighter tolerances.Campbell, pp. 158–169

The development of smokeless powder

Finnish smokeless powder

Smokeless powder is a type of propellant used in firearms and artillery that produces less smoke and less fouling when fired compared to black powder. Because of their similar use, both the original black powder formula ...

, based on nitroglycerine or nitrocellulose, by the French inventor Paul Vielle in 1884 was a further step allowing smaller charges of propellant with longer barrels. The guns of the pre-Dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

s of the 1890s tended to be smaller in caliber compared to the ships of the 1880s, most often 12 in (305 mm), but progressively grew in length of barrel, making use of improved propellants to gain greater muzzle velocity.

The nature of the projectiles also changed during the ironclad period. Initially, the best armor-piercing projectile was a solid cast-iron shot. Later, shot of chilled iron, a harder iron alloy, gave better armor-piercing qualities. Eventually the armor-piercing shell

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate armour protection, most often including naval armour, body armour, and vehicle armour.

The first, major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat th ...

was developed.

Positioning of armament

Broadside ironclads

ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

, carried their weapons in a single line along their sides and so were called " broadside ironclads".''Conways's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905'' pp. 7–11, 118–119, 173, 267–268, 286–287, 301, 337–339, 389 Both and were examples of this type. Because their armor was so heavy, they could only carry a single row of guns along the main deck on each side rather than a row on each deck.

A significant number of broadside ironclads were built in the 1860s, principally in Britain and France, but in smaller numbers by other powers including Italy, Austria, Russia and the United States. The advantages of mounting guns on both broadsides was that the ship could engage more than one adversary at a time, and the rigging did not impede the field of fire.Beeler, pp. 91–93

Broadside armament also had disadvantages, which became more serious as ironclad technology developed. Heavier guns to penetrate ever-thicker armor meant that fewer guns could be carried. Furthermore, the adoption of ramming as an important tactic meant the need for ahead and all-round fire. These problems led to broadside designs being superseded by designs that gave greater all-round fire, which included central-battery, turret, and barbette designs.

Turrets, batteries, and barbettes

There were two main design alternatives to the broadside. In one design, the guns were placed in an armored casemate amidships: this arrangement was called the 'box-battery' or 'center-battery'. In the other, the guns could be placed on a rotating platform to give them a broad field of fire; when fully armored, this arrangement was called a

There were two main design alternatives to the broadside. In one design, the guns were placed in an armored casemate amidships: this arrangement was called the 'box-battery' or 'center-battery'. In the other, the guns could be placed on a rotating platform to give them a broad field of fire; when fully armored, this arrangement was called a turret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Optical microscope#Objective turret (revolver or revolving nose piece), Objective turre ...

and when partially armored or unarmored, a barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

.

The centre-battery was the simpler and, during the 1860s and 1870s, the more popular method. Concentrating guns amidships meant the ship could be shorter and handier than a broadside type. The first full-scale center-battery ship was of 1865; the French laid down centre-battery ironclads in 1865 which were not completed until 1870. Centre-battery ships often, but not always, had a recessed freeboard enabling some of their guns to fire directly ahead.

The turret was first used in naval combat on in 1862, with a type of turret designed by the Swedish engineer John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American engineer and inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive Novelty (lo ...

. A competing turret design was proposed by the British inventor Cowper Coles with a prototype of this installed on in 1861 for testing and evaluation purposes. Ericsson's turret turned on a central spindle, and Coles's turned on a ring of bearings. Turrets offered the maximum arc of fire

The field of fire or zone of fire (ZF) of a weapon, or group of weapons, is the area around it that can easily and effectively be reached by projectiles from a given position.

Field of fire

The term originally came from the ''field of fire'' in f ...

for the guns, but there were significant problems with their use in the 1860s. The fire arc of a turret would be considerably limited by masts and rigging, so they were unsuited to use on the earlier ocean-going ironclads. The second problem was that turrets were extremely heavy. Ericsson was able to offer the heaviest possible turret (guns and armor protection) by deliberately designing a ship with very low freeboard. The weight thus saved from having a high broadside above the waterline was diverted to actual guns and armor. Low freeboard, however, also meant a smaller hull and therefore a smaller capacity for coal storage—and therefore range of the vessel. In many respects, the turreted, low-freeboard ''Monitor'' and the broadside sailor HMS ''Warrior'' represented two opposite extremes in what an 'Ironclad' was all about. The most dramatic attempt to compromise these two extremes, or 'squaring this circle', was designed by Captain Cowper Phipps Coles: . It was a dangerously low freeboard turret ship, which nevertheless carried a full rig of sail and subsequently capsized not long after her launch in 1870. Her half-sister was restricted to firing from her turrets only on the port and starboard beams. The third Royal Navy ship to combine turrets and masts was of 1876, which carried two turrets on either side of the center-line, allowing both to fire fore, aft and broadside.

A lighter alternative to the turret, particularly popular with the French navy, was the barbette. These were fixed armored towers which held a gun on a turntable. The crew was sheltered from direct fire, but vulnerable to plunging fire

Plunging fire is a form of indirect fire, where gunfire is fired at a trajectory to make it fall on its target from above. It is normal at the high trajectories used to attain long range, and can be used deliberately to attack a target not susce ...

, for instance from shore emplacements. The barbette was lighter than the turret, needing less machinery and no roof armor. Some barbettes were stripped of their armor plate to reduce the top-weight of their ships. The barbette became widely adopted in the 1880s, and with the addition of an armored 'gun-house', transformed into the turrets of the pre-dreadnought battleships.

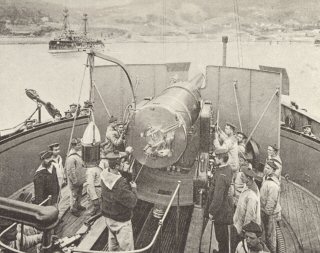

Torpedoes

The ironclad age saw the development of explosivetorpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es as naval weapons, which helped complicate the design and tactics of ironclad fleets. The first torpedoes were static mines, used extensively in the American Civil War. That conflict also saw the development of the spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

, an explosive charge pushed against the hull of a warship by a small boat. For the first time, a large warship faced a serious threat from a smaller one—and given the relative inefficiency of shellfire against ironclads, the threat from the spar torpedo was taken seriously. The U.S. Navy converted four of its monitors to become turretless armored spar-torpedo vessels while under construction in 1864–1865, but these vessels never saw action. Another proposal, the towed or 'Harvey' torpedo, involved an explosive on a line or outrigger; either to deter a ship from ramming or to make a torpedo attack by a boat less suicidal.

A more practical and influential weapon was the self-propelled or Whitehead torpedo. Invented in 1868 and deployed in the 1870s, it formed part of the armament of ironclads of the 1880s like HMS ''Inflexible'' and the Italian . The ironclad's vulnerability to the torpedo was a key part of the critique of armored warships made by the school of naval thought; it appeared that any ship armored enough to prevent destruction by gunfire would be slow enough to be easily caught by torpedo. In practice, however, the ''Jeune Ecole'' was only briefly influential and the torpedo formed part of the confusing mixture of weapons possessed by ironclads.

Armor and construction

The first ironclads were built on wooden or iron hulls, and protected by wrought iron armor backed by thick wooden planking. Ironclads were still being built with wooden hulls into the 1870s.

The first ironclads were built on wooden or iron hulls, and protected by wrought iron armor backed by thick wooden planking. Ironclads were still being built with wooden hulls into the 1870s.

Hulls: iron, wood, and steel

Usingwrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

construction for warships offered advantages for the engineering of the hull. However, unarmored iron had many military disadvantages, and offered technical problems which kept wooden hulls in use for many years, particularly for long-range cruising warships.

Iron ships had first been proposed for military use in the 1820s. In the 1830s and 1840s, France, Britain and the United States had all experimented with iron-hulled but unarmored gunboats and frigates. However, the iron-hulled frigate was abandoned by the end of the 1840s, because iron hulls were more vulnerable to solid shot; iron was more brittle than wood, and iron frames more likely to fall out of shape than wood.

The unsuitability of unarmored iron for warship hulls meant that iron was only adopted as a building material for battleships when protected by armor. However, iron gave the naval architect many advantages. Iron allowed larger ships and more flexible design, for instance the use of watertight bulkheads on the lower decks. ''Warrior'', built of iron, was longer and faster than the wooden-hulled ''Gloire''. Iron could be produced to order and used immediately, in contrast to the need to give wood a long period of seasoning

Seasoning is the process of supplementing food via herbs, spices, and/or salts, intended to enhance a particular flavour.

General meaning

Seasonings include herbs and spices, which are themselves frequently referred to as "seasonings". Salt may ...

. And, given the large quantities of wood required to build a steam warship and the falling cost of iron, iron hulls were increasingly cost-effective. The main reason for the French use of wooden hulls for the ironclad fleet built in the 1860s was that the French iron industry could not supply enough, and the main reason why Britain built its handful of wooden-hulled ironclads was to make best use of hulls already started and wood already bought.

Wooden hulls continued to be used for long-range and smaller ironclads, because iron nevertheless had a significant disadvantage. Iron hulls suffered quick fouling

Fouling is the accumulation of unwanted material on solid surfaces. The fouling materials can consist of either living organisms (biofouling, organic) or a non-living substance (inorganic). Fouling is usually distinguished from other surfac ...

by marine life, slowing the ships down—manageable for a European battlefleet close to dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

s, but a difficulty for long-range ships. The only solution was to sheath the iron hull first in wood and then in copper, a laborious and expensive process which made wooden construction remain attractive. Iron and wood were to some extent interchangeable: the Japanese and ordered in 1875 were sister-ships, but one was built of iron and the other of composite construction.

After 1872, steel started to be introduced as a material for construction. Compared to iron, steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

allows for greater structural strength for a lower weight. The French Navy led the way with the use of steel in its fleet, starting with the , laid down in 1873 and launched in 1876. ''Redoutable'' nonetheless had wrought iron armor plate, and part of her exterior hull was iron rather than steel.

Even though Britain led the world in steel production, the Royal Navy was slow to adopt steel warships. The Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is steelmaking, removal of impurities and undesired eleme ...

for steel manufacture produced too many imperfections for large-scale use on ships. French manufacturers used the Siemens-Martin process

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to produce steel. Because steel is difficult to manufacture owing to its high mel ...

to produce adequate steel, but British technology lagged behind. The first all-steel warships built by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

were the dispatch vessels ''Iris'' and ''Mercury'', laid down in 1875 and 1876.

Armor and protection schemes

Iron-built ships used wood as part of their protection scheme. HMS ''Warrior'' was protected by 4.5 in (114 mm) ofwrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

backed by 15 in (381 mm) of teak

Teak (''Tectona grandis'') is a tropical hardwood tree species in the family Lamiaceae. It is a large, deciduous tree that occurs in mixed hardwood forests. ''Tectona grandis'' has small, fragrant white flowers arranged in dense clusters (panic ...

, the strongest shipbuilding wood. The wood played two roles, preventing spalling

Spall are fragments of a material that are broken off a larger solid body. It can be produced by a variety of mechanisms, including as a result of projectile impact, corrosion, weathering, cavitation, or excessive rolling pressure (as in a ball ...

and also preventing the shock of a hit damaging the structure of the ship. Later, wood and iron were combined in 'sandwich' armor, for instance in HMS ''Inflexible''.

Steel was also an obvious material for armor. It was tested in the 1860s, but the steel of the time was too brittle

A material is brittle if, when subjected to stress, it fractures with little elastic deformation and without significant plastic deformation. Brittle materials absorb relatively little energy prior to fracture, even those of high strength. ...

and disintegrated when struck by shells. Steel became practical to use when a way was found to fuse steel onto wrought iron plates, giving a form of compound armor

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive struct ...