Bordigism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

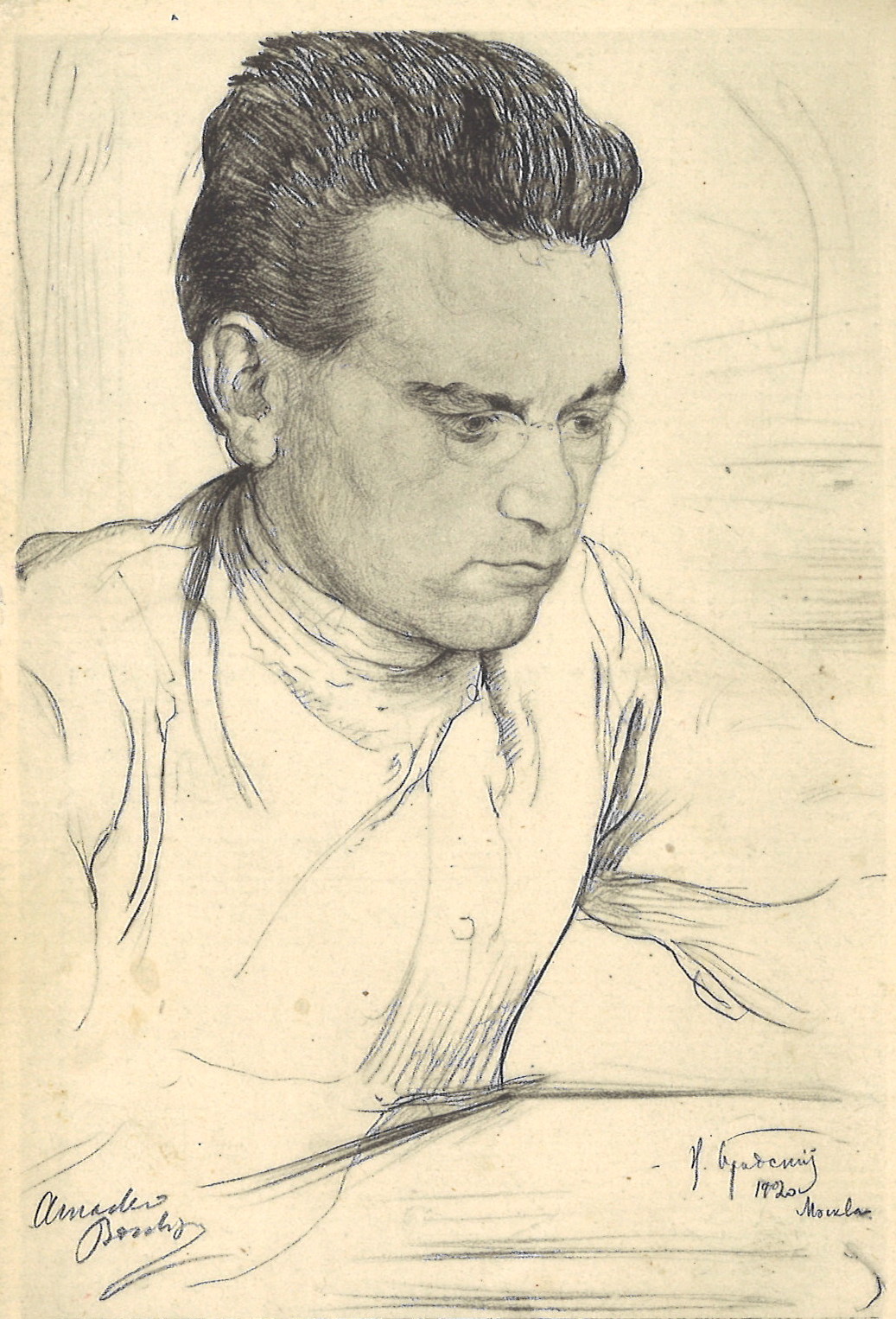

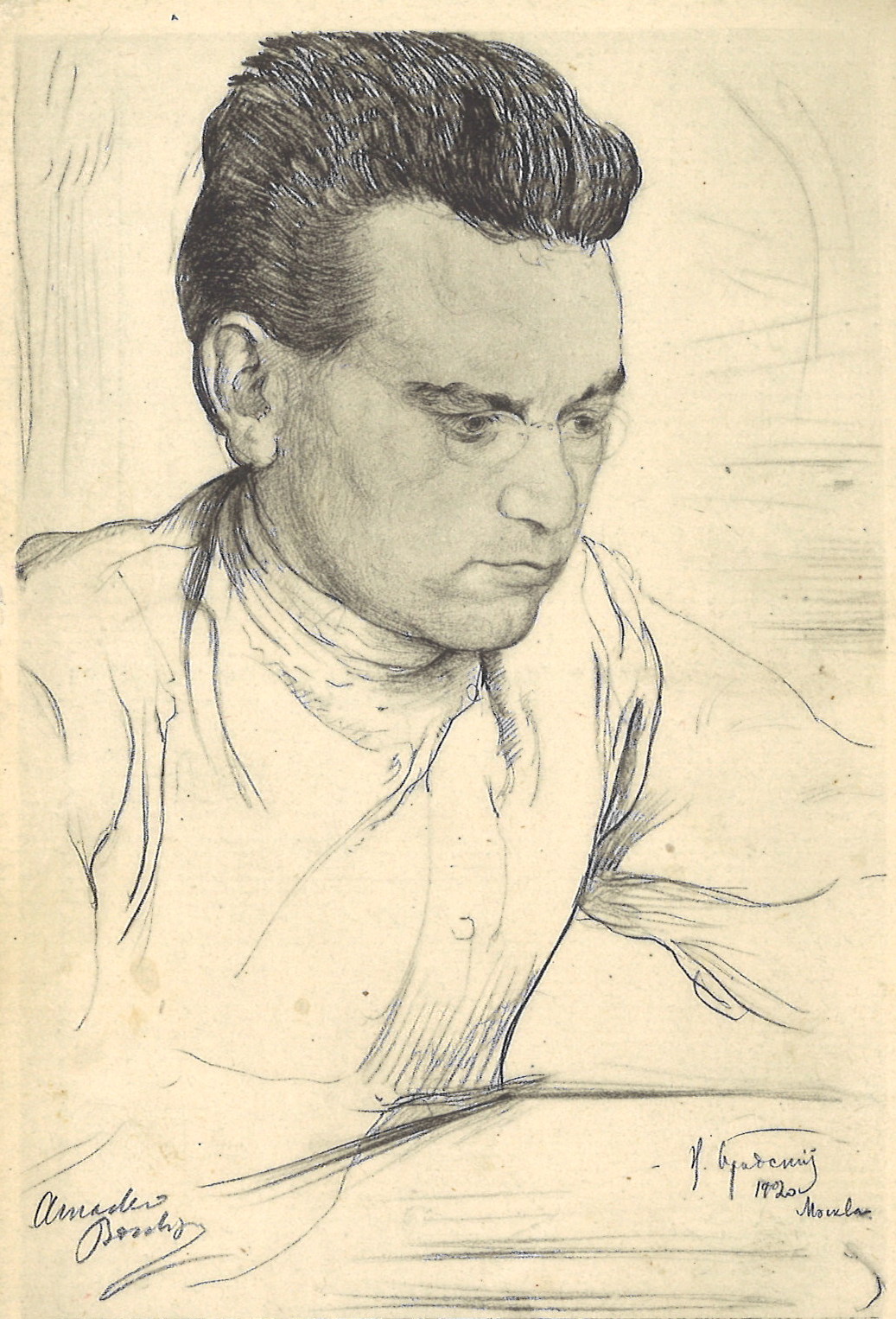

Amadeo Bordiga (13 June 1889 – 25 July 1970) was an Italian

When the PSI held its congress at

When the PSI held its congress at

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

theorist. A revolutionary socialist

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolu ...

, Bordiga was the founder of the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

(PCdI), a member of the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

(Comintern), and later a leading figure of the Internationalist Communist Party (PCInt). He was originally associated with the PCdI but was expelled in 1930 after being accused of Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

. Bordiga is viewed as one of the most notable representatives of left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions ...

in Europe.

Early life, family, and education

Bordiga was born at Resina in theprovince of Naples

The province of Naples (; ) was a province in the Campania region of Italy.

In 2014/2015, the reform of local authorities (Law 142/1990 and Law 56/2014), replaced the province of Naples with the Metropolitan City of Naples.

Demographics

The p ...

in 1889. His father, Oreste Bordiga, was an esteemed scholar of agricultural science

Agricultural science (or agriscience for short) is a broad multidisciplinary field of biology that encompasses the parts of exact, natural, economic and social sciences that are used in the practice and understanding of agriculture. Professio ...

, whose authority was especially recognized in regard to the centuries-old agricultural problems of Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

. His mother, Zaira degli Amadei, was descended from an ancient Florentine family and his maternal grandfather Count Michele Amadei was a conspirator in the struggles of the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

. His paternal uncle, Giovanni Bordiga, another militant of the ''Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

'', was a mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

and professor at the University of Padua

The University of Padua (, UNIPD) is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza; thus, it is the second-oldest ...

.

Bordiga's upbringing, while being thoroughly radical, was also of a highly scientific nature. An opponent of the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish (, "Tripolitanian War", , "War of Libya"), also known as the Turco-Italian War, was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captur ...

as an Italian colonial war in Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, Bordiga was introduced to the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

(PSI) by his high-school physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

teacher in 1910. Bordiga eventually founded the Karl Marx Circle in 1912, where he would meet his first wife, Ortensia De Meo. Bordiga graduated with a degree in engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

from University of Naples Federico II

The University of Naples Federico II (; , ) is a public university, public research university in Naples, Campania, Italy. Established in 1224 and named after its founder, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, it is the oldest public, s ...

in 1912. Bordiga married De Meo in 1914. They had two children, Alma and Oreste. Ortensia died in 1955, and Bordiga married Ortensia's sister, Antonietta De Meo, ten years later in 1965.

Political career

Italian Socialist Party

Within the newly founded Karl Marx Circle, Bordiga rejected apedagogical

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

approach to political work and developed a "theory of the Party", whereby the organization was meant to display non-immediate goals as a rally of similarly minded people and not necessarily a body of the working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

. Bordiga was deeply opposed to representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

, which he associated with bourgeois electoralism. In a 1914 issue of ''Il Socialista'', he wrote: "Thus if there is a complete negation of the theory of democratic action it is to be found in socialism." Bordiga opposed the parliamentary faction of the PSI being autonomous from central control. In common with most socialists in Latin countries, Bordiga campaigned against Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, which he identified as a non-secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

group.

Following the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, Bordiga rallied to the communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

movement and formed the communist abstention

Abstention is a term in election procedure for when a participant in a Voting, vote either does not go to vote (on election day) or, in parliamentary procedure, is present during the vote but does not cast a ballot. Abstention must be contrast ...

ist faction within the PSI, abstentionist in that it opposed participation in bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

elections. The group would form with the addition of the former '' L'Ordine Nuovo'' grouping in Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

around Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Francesco Gramsci ( , ; ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist philosophy, Marxist philosopher, Linguistics, linguist, journalist, writer, and politician. He wrote on philosophy, Political philosophy, political the ...

the backbone of the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

(PCdI). This came after a long internal struggle in the PSI as it had voted as early as 1919 to affiliate with the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

but had refused to purge its reformist

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

wing. In the course of the conflict, Bordiga attended the 2nd Comintern Congress in 1920, where he added two points to the Twenty-one Conditions

The Twenty-one Conditions, officially the Conditions of Admission to the Communist International, are the conditions, most of which were suggested by Vladimir Lenin, to the adhesion of the socialist parties to the Third International (Comintern) cr ...

of membership proposed by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

. Nevertheless, he was criticised by Lenin in his work '' "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder'' (1920) over a disagreement regarding parliamentary abstentionism. Victor Serge

Victor Serge (; born Viktor Lvovich Kibalchich, ; 30 December 1890 – 17 November 1947) was a Belgian-born Russian revolutionary, novelist, poet, historian, journalist, and translator. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks in Janu ...

, who witnessed the 2nd Comintern Congress, remembered Bordiga as "exuberant and energetic, features blunt, hair thick, black and bristly, a man quivering under his encumbrance of ideas, experiences and dark forecasts."

Communist Party of Italy

When the PSI held its congress at

When the PSI held its congress at Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

in January 1921, representatives sent by Comintern, all insisted that the party must expel its reformist wing led by Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 – 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and particip ...

but were divided over whether to continue to work with Giacinto Menotti Serrati

Giacinto Menotti Serrati (; 25 November 1872 – 10 May 1926) was an Italian communist politician and newspaper editor.

Biography

He was born in Spotorno. He was a central leader of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), editor of the paper ''Avant ...

, who advised delaying the split. Bordiga advocated an immediate break with both Serrati and Turati, and hence with the majority of the PSI, and prevailed against the opposition of the leading Comintern representative Paul Levi

Paul Levi (; 11 March 1883 – 9 February 1930) was a German communist and social democratic political leader. He was the head of the Communist Party of Germany following the assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in 1919. After bein ...

but also with the backing of others, including Matyas Rakosi, the future Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

dictator of Hungary.

After the congress, Bordiga emerged as leader of the newly formed Communist Party of Italy. He was one of five members of the executive but was "the actual director of all party activity". For Bordiga, the party was the social brain of the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

whose task was not to seek majority support but to concentrate on working for an armed insurrection in the course of which it would seize power and then use it to abolish capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and impose a communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of ...

by force. Bordiga identified with the dictatorship of the proletariat and the dictatorship of the party, and argued that establishing its own dictatorship should be the party's immediate and direct aim. This position was accepted by the majority of the members of the PCdI but was to bring them into conflict with the Comintern when in 1921 the latter adopted a new tactic, i.e. that of the united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

with reformist organisations to fight for social reforms and even to form a workers' government. Bordiga regarded this as a reversion to the failed tactics which the pre-war social democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

had adopted and which had led to them becoming reformists.

Out of a regard for discipline, Bordiga and his comrades (who became known as the Italian communist left) accepted the Comintern decision but were in an increasingly difficult position. When Bordiga was arrested in February 1923 on a trumped-up charge by the new government of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, he had to give up his post as a member of the Central Committee of the PCdI. On his acquittal later that year, Bordiga decided not to reclaim it, therefore implicitly accepting that he was now an oppositionist.

At the Fifth Congress of Comintern in Moscow held in June–July 1924, Bordiga was the sole voice of the ultra-left who opposed any cooperation with socialist parties in favour of a "united front from below, not from above", which received support except within the Italian delegation. He argued that the rise of Mussolini and the Italian fascists

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

was only "a change in the governing personnel of the bourgeois class." Also in 1924, the Italian communist left lost control of the PCdI to a pro-Moscow group whose leader Gramsci became the party's General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

in June. In March 1925, Bordiga refused to go to Moscow to attend a plenum of Comintern's executive, and in his absence was accused of taking up a "hostile position against Comintern by declaring his complete solidarity with Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

".

At the Third Congress of the PCdI held in exile in Lyons in January 1926, the manoeuvre of the pro-Moscow group was completed. Without the support of the Communist International to escape from Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

control, few members of the Italian communist left were able to arrive at the Congress, so the theses drawn up by Bordiga were rejected. Those of the Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

minority group accepted.

Under arrest

In December 1926, Bordiga was again arrested by Mussolini and sent to prison inUstica

Ustica (; ) is a small Italian island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is about across and is situated north of Capo Gallo, Sicily. Roughly 1,300 people live in the ''comune'' (municipality) of the same name. There is a regular ferry service ...

, an Italian island in the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (, ; or ) , , , , is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenian people identified with the Etruscans of Italy.

Geography

The sea is bounded by the islands of C ...

, where he met with Gramsci and they renewed their friendship and worked alongside each other despite their political differences. Bordiga was concerned about Gramsci's ill health but nothing came of a plan to help him escape the island. In 1928, Bordiga was moved to the Isle of Ponza

Ponza (Italian: ''isola di Ponza'' ) is the largest island of the Italy, Italian Pontine Islands archipelago, located south of Cape Circeo in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is also the name of the commune of the island, a part of the province of Latina ...

, where he built several houses, returning after his detention in 1929 to finish them.

Opposition

Following his release, Bordiga did not resume his activities in the PCdI and was in fact expelled in March 1930, accused of having "supported, defended and endorsed the positions of theTrotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

opposition" and been organisationally disruptive. With his expulsion, Bordiga left political activity until 1943 and he was to refuse to comment on political affairs even when asked by trusted friends; many of his former supporters in the PCdI went into exile and founded a political tendency often referred to as Italian communist left.

In 1928, its members in exile in France and Belgium formed themselves into the Left Fraction of the Communist Party of Italy, which became, in 1935, the Italian Fraction of the Communist Left. This change of name was a reflection of the Italian communist left's view that the PCdI and the other Communist parties had now become counter-revolutionary. A faction of the party, with their theory of the party and their opposition to any form of frontism, held that the program was everything and a gate-receipt notion of numbers was nothing. Bordiga would again work with many of these comrades following the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

According to the reports of Angelo Alliotta, a secret informant of the fascist police in Italy who visited Bordiga's home in Formia where he holidayed with his wife, Bordiga showed support for the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

. According to Alliotta, Bordiga believed Nazi Germany was weakening the "English giant", which to him was "the greatest exponent of capitalism", and thus the defeat of Britain would bring about revolutionary conditions in Europe. Bordiga also criticised Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

for allying with the western Allies against the Axis in April 1943. Other sources cast doubt on the analysis that Bordiga supported Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy, citing ‘contradictory’ testimony on the issue. He supported the ‘proletarian’ partisan movements, as well as the anti-fascist Warsaw uprisings of 1943 (Warsaw ghetto) and 1944.

International Communist Party

After 1944, Bordiga first returned to political activity in theNaples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

-based Fraction of Socialists and Communists. When this grouping was dissolved into the Internationalist Communist Party (PCInt), Bordiga did not initially join; despite this, he contributed anonymously to its press, primarily ''Battaglia Comunista'' and ''Prometeo'', in keeping with his conviction that revolutionary work was collective in nature and his opposition to any form of even incipient personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an ideali ...

. Bordiga joined the PCInt in 1949. When the current split in two in 1951, he took the side of the grouping that took on the name International Communist Party, publishing its ''Il Programma Comunista''. Bordiga devoted himself to the party, contributing extensively. Bordiga remained with the ICP until his death at Formia

Formia (ancient Formiae) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Latina, on the Mediterranean , Italy. It is located halfway between Rome and Naples, and lies on the Roman-era Appian Way.

Mythology

According to the mythology the city was f ...

in 1970.

Theories and beliefs

Bordigism is a variant ofleft communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions ...

espoused by Bordiga. Bordigists in the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

would be the first to refuse on principle any participation in parliamentary election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. General elections ...

s.

On Marxism–Leninism

On the theoretical level, Bordiga developed an understanding of theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as a capitalist society

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by a n ...

. Bordiga's writings on the capitalist nature of the Soviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy ...

in contrast to those produced by the Trotskyists

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as a ...

also focused on the agrarian sector. In analyzing the agriculture in the Soviet Union

Agriculture in the Soviet Union was mostly collectivized, with some limited cultivation of private plots. It is often viewed as one of the more inefficient sectors of the economy of the Soviet Union. A number of food taxes ( prodrazverstka, ...

, Bordiga sought to display the capitalist social relations that existed in the kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz. These were the two components of the socialized farm sector that began to eme ...

and sovkhoz

A sovkhoz ( rus, совхо́з, p=sɐfˈxos, a=ru-sovkhoz.ogg, syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated from , ''sovetskoye khozyaystvo''; ) was a form of state-owned farm or agricultural enterprise in the Soviet Union.

It is usually contrasted w ...

, one a cooperative farm and the other a wage-labor state farm. In particular, he emphasized how much of the national agrarian produce came from small privately owned plots (writing in 1950) and predicted the rates at which the Soviet Union would start importing wheat after Imperial Russia

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor/empress, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* ...

had been such a large exporter from the 1880s to 1914.

In Bordiga's conception of Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, and later Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, Ho Chi Minh

(born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), colloquially known as Uncle Ho () among other aliases and sobriquets, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and politician who served as the founder and first President of Vietnam, president of the ...

, and so on, were great Romantic revolutionaries, i.e. bourgeois revolutionaries. He felt that the Marxist–Leninist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

s that came into existence after 1945 were extending the bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

nature of prior revolutions that degenerated as all had in common a policy of expropriation and agrarian and productive development, which he considered negations of previous conditions and not the genuine construction of socialism.

On democracy

Bordiga defined himself as anti-democratic, believing himself to be following the tradition ofKarl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.single-party state, as he saw

instead of in 1927 with the defeat of Trotsky)

without simply calling for more democracy. The abstract formal perspective of bureaucracy/democracy, with which the Trotskyist tradition treats this crucial period in Comintern history, became separated from any content. Bordiga throughout his life called himself a

Jacques Camatte began corresponding with Bordiga from the age of 19 in 1954, and Bordiga developed a long-standing relationship with Camatte and ideological influence over him. Camatte's early work very much reads in line with the Bordigist current, and Bordiga frequently contributed to Camatte's journal '' Invariance'' near the end of his life. Even after Camatte's break with Marxism following Bordiga's death, Camatte's preoccupation within the subject of ''Gemeinwesen'' (community, commonwealth) within Marx's work was consistent with Bordiga's emphasis on the anti-individualist and collectivist aspects of Marxism. Bordiga also influenced Gilles Dauvé, and had great influence over the ultra-leftist currents of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Amadeo Bordiga Foundation was established in 1998 in Formia, in the house where Bordiga spent the last several months of his life. The foundation organizes publications of Bordiga's works and encourages further expansions upon his ideas. In August 2020, ''

Jacques Camatte began corresponding with Bordiga from the age of 19 in 1954, and Bordiga developed a long-standing relationship with Camatte and ideological influence over him. Camatte's early work very much reads in line with the Bordigist current, and Bordiga frequently contributed to Camatte's journal '' Invariance'' near the end of his life. Even after Camatte's break with Marxism following Bordiga's death, Camatte's preoccupation within the subject of ''Gemeinwesen'' (community, commonwealth) within Marx's work was consistent with Bordiga's emphasis on the anti-individualist and collectivist aspects of Marxism. Bordiga also influenced Gilles Dauvé, and had great influence over the ultra-leftist currents of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Amadeo Bordiga Foundation was established in 1998 in Formia, in the house where Bordiga spent the last several months of his life. The foundation organizes publications of Bordiga's works and encourages further expansions upon his ideas. In August 2020, ''

The International Library of the Communist Left – Bordiga Page

at Marxists.org.

at "n+1" Review.

Libertarian Communist Library Amadeo Bordiga archive

25 October 2009).

25 October 2009.

* ttp://www.international-communist-party.org/ International Communist Party

Earlene Craver The Third Generation: The Young Socialists in Italy, 1907–1915

Philippe Bourrinet, The "Bordigist" Current, (1912–1952)

a

"Left Wing" Communism – an infantile disorder?

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bordiga, Amadeo 1889 births 1970 deaths 20th-century Italian engineers 20th-century Italian journalists 20th-century Italian politicians Critics of Freemasonry Anti-Stalinist left Executive Committee of the Communist International Italian anti-capitalists Italian atheists Italian male journalists Italian Marxists Italian Communist Party politicians Italian Socialist Party politicians Italian socialists Left communists Marxist theorists People from Formia People from the Metropolitan City of Naples

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.single-party state, as he saw

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

and Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

as the culmination of bourgeois democracy. Followers of Bordiga often state that there is no functional difference between democracy and dictatorship, as one class will inevitably establish control. To Bordiga, democracy meant above all the manipulation of society as a formless mass. To this, he counterposed the dictatorship of the proletariat, to be implemented by the Communist party based on the principles and program enunciated in ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'' (), originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (), is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The ...

'' (1848). He often referred to the spirit of Engels' remark that "on the eve of the revolution all the forces of reaction will be against us under the banner of 'pure democracy'" as every factional opponent of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

in 1921 from the monarchists (the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

) to the anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

, such as the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine (; RIAU), also known as ''Makhnovtsi'' (), named after their founder Nestor Makhno, was an Anarchism, anarchist army formed largely of Ukrainians, Ukrainian peasants and workers during the Russian C ...

, called for soviets

The Soviet people () were the citizens and nationals of the Soviet Union. This demonym was presented in the ideology of the country as the "new historical unity of peoples of different nationalities" ().

Nationality policy in the Soviet Union ...

without Bolsheviks—or soviet workers councils not dominated by Bolsheviks. As such, Bordiga opposed the idea of revolutionary theory being the product of a democratic process of pluralist views, believing that the Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

perspective has the merit of underscoring the fact that, like all social formations, communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

is above all about the expression of programmatic content. This enforces the fact that, for Marxists, communism is not an ideal to be achieved but a real movement born from the old society with a set of programmatic tasks.

On the united front

Bordiga resolutely opposed theComintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

's turn to the right in 1921. As leader of the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

, he refused to implement the united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

strategy of the Third Congress. He also refused to fuse the newly formed party with the left-wing of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

from which it had just broken away. Bordiga had a completely different view of the party from the Comintern, which was adapting to the revolutionary ebb that was announced in 1921 by the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

, the implementation of the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

, the banning of factions, and the defeat of the March Action

The March Action ( or , i.e. "The March battles in Central Germany") was a failed communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communi ...

in Germany. For Bordiga, the Western European Communist parties' strategy of fighting this ebb by absorbing a mass of left-wing social democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

through the united front was a complete capitulation to the period of counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution has occurred, in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "c ...

ebb he saw setting in. This was the base of his critique of democracy, for it was in the name of conquering the masses that the Comintern seemed to be making all kinds of programmatic concessions to left-wing social democrats. For Bordiga, program was everything, a gate-receipt notion of numbers was nothing. The role of the party in the period of ebb was to preserve the program and to carry on the propaganda work possible until the next turn of the tide, not to dilute it while chasing ephemeral popularity.

Bordiga's analysis provided a way of seeing a fundamental degeneration in the world communist movement in 1921instead of in 1927 with the defeat of Trotsky)

without simply calling for more democracy. The abstract formal perspective of bureaucracy/democracy, with which the Trotskyist tradition treats this crucial period in Comintern history, became separated from any content. Bordiga throughout his life called himself a

Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

and never polemicised against Lenin directly; his totally different appreciation of the 1921 conjuncture, its consequences for the Comintern and his opposition to Lenin and Trotsky on the united front issue illuminates a turning point that is generally obscured by the heirs of the Trotskyist wing of the international left opposition of the 1920s.

On communism

Although most Leninists distinguish betweensocialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

and he did consider himself a Leninist, Bordiga did not distinguish between the two in the same way Leninists do. Bordiga did not see socialism as a separate mode of production from communism but rather just as how communism looks as it emerges from capitalism before it has "developed on its own foundations". Bordiga used ''socialism'' to mean what Marx called the lower-phase communism. Sticking to Marx's concept of communism, for Bordiga both stages of socialist or communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of ...

—with stages referring to historical materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

—were characterised by the absence of money, capital, the market, and so on, the difference between them being that earlier in the first stage rationing would be done in a way in which "a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form", with deductions being made from said labor to fund public projects, and difference in interests between the rural and urban proletariat would exist, whilst in communism "bourgeoisie law" would be no more, hence the equal standard applied to all peoples no longer would apply, and the alienated man "will not aim to win back his person" but rather become a new "Social Man". Arguing against what Bordiga saw as the bourgeois idea of "free producer economies", he instead declared that under communism, whether it be the lower stage or higher stage, production and consumption are both enslaved to society.

This view distinguished Bordiga from other Leninists and especially the Trotskyists, who tended and still tend to telescope the first two stages and so have money and the other exchange categories surviving into socialism; Bordiga would have none of this. For him, no society in which money, buying, and selling and the rest survived could be regarded as either socialist or communist—these exchange categories would die out before the socialist rather than the communist stage was reached. Within the Marxist movement, ''socialism'' was popularised during the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

by Lenin. This view is consistent with and helped to inform early concepts of socialism in which the law of value

The law of the value of commodities (German: ''Wertgesetz der Waren''), known simply as the law of value, is a central concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy first expounded in his polemic ''The Poverty of Philosophy'' (1847) agains ...

no longer directs economic activity. Monetary relations in the form of exchange-value, profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

, interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct f ...

, and wage labour

Wage labour (also wage labor in American English), usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labour, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labour power under ...

would not operate and apply to Marxist socialism.

Legacy

Jacques Camatte began corresponding with Bordiga from the age of 19 in 1954, and Bordiga developed a long-standing relationship with Camatte and ideological influence over him. Camatte's early work very much reads in line with the Bordigist current, and Bordiga frequently contributed to Camatte's journal '' Invariance'' near the end of his life. Even after Camatte's break with Marxism following Bordiga's death, Camatte's preoccupation within the subject of ''Gemeinwesen'' (community, commonwealth) within Marx's work was consistent with Bordiga's emphasis on the anti-individualist and collectivist aspects of Marxism. Bordiga also influenced Gilles Dauvé, and had great influence over the ultra-leftist currents of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Amadeo Bordiga Foundation was established in 1998 in Formia, in the house where Bordiga spent the last several months of his life. The foundation organizes publications of Bordiga's works and encourages further expansions upon his ideas. In August 2020, ''

Jacques Camatte began corresponding with Bordiga from the age of 19 in 1954, and Bordiga developed a long-standing relationship with Camatte and ideological influence over him. Camatte's early work very much reads in line with the Bordigist current, and Bordiga frequently contributed to Camatte's journal '' Invariance'' near the end of his life. Even after Camatte's break with Marxism following Bordiga's death, Camatte's preoccupation within the subject of ''Gemeinwesen'' (community, commonwealth) within Marx's work was consistent with Bordiga's emphasis on the anti-individualist and collectivist aspects of Marxism. Bordiga also influenced Gilles Dauvé, and had great influence over the ultra-leftist currents of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Amadeo Bordiga Foundation was established in 1998 in Formia, in the house where Bordiga spent the last several months of his life. The foundation organizes publications of Bordiga's works and encourages further expansions upon his ideas. In August 2020, ''Historical Materialism

Historical materialism is Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx located historical change in the rise of Class society, class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods.

Karl Marx stated that Productive forces, techno ...

'' published ''The Science and Passion of Communism'', an anthology of English translations of Bordiga's work.

References

Sources

* * * *External links

The International Library of the Communist Left – Bordiga Page

at Marxists.org.

at "n+1" Review.

Libertarian Communist Library Amadeo Bordiga archive

25 October 2009).

25 October 2009.

* ttp://www.international-communist-party.org/ International Communist Party

Earlene Craver The Third Generation: The Young Socialists in Italy, 1907–1915

Philippe Bourrinet, The "Bordigist" Current, (1912–1952)

a

"Left Wing" Communism – an infantile disorder?

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bordiga, Amadeo 1889 births 1970 deaths 20th-century Italian engineers 20th-century Italian journalists 20th-century Italian politicians Critics of Freemasonry Anti-Stalinist left Executive Committee of the Communist International Italian anti-capitalists Italian atheists Italian male journalists Italian Marxists Italian Communist Party politicians Italian Socialist Party politicians Italian socialists Left communists Marxist theorists People from Formia People from the Metropolitan City of Naples