Bohuslav EÄŤer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bohuslav Ečer (31 July 1893 – 14 March 1954) was a Czechoslovak general of the judicial service and professor of

In 2001, Bohuslav EÄŤer was awarded the ''in memoriam''

In 2001, Bohuslav EÄŤer was awarded the ''in memoriam''

international criminal law

International criminal law (ICL) is a body of public international law designed to prohibit certain categories of conduct commonly viewed as serious atrocities and to make perpetrators of such conduct criminally accountable for their perpetrat ...

. He was also a member of the United Nations Commission for the Investigation of War Crimes, chairman of the Czechoslovak delegation to the International Military Tribunal

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

for the Punishment of War Criminals in Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

and an ''ad hoc'' judge of the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

.

Life

Before the occupation

EÄŤer was born on 31 July 1893. He was born into a family of a merchant, later a railway worker. He graduated in 1911 from the classical gymnasium inKroměřĂĹľ

KroměřĂĹľ (; ) is a town in the ZlĂn Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 28,000 inhabitants. It is known for KroměřĂĹľ Castle with its castle gardens, which are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The historic town centre with the castle ...

, then he enrolled at the law faculty of University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

, but he did not graduate because he had to enlist in the army in 1915. After the war, he completed his legal studies at Charles University

Charles University (CUNI; , UK; ; ), or historically as the University of Prague (), is the largest university in the Czech Republic. It is one of the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest universities in the world in conti ...

in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, where he received his Doctorate of Law

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

in 1920, and for a short time was a trainee at the district court

District courts are a category of courts which exists in several nations, some call them "small case court" usually as the lowest level of the hierarchy.

These courts generally work under a higher court which exercises control over the lower co ...

in KroměřĂĹľ, and later at the territorial court in Brno.

Eventually, however, he established his own law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

practice specializing in criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It proscribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and Well-being, welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal l ...

in Brno

Brno ( , ; ) is a Statutory city (Czech Republic), city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava (river), Svitava and Svratka (river), Svratka rivers, Brno has about 403,000 inhabitants, making ...

, where he also married Ludmila Galleová in 1922. The couple eventually had two daughters, Naděžda (born 1922) and Jarmila (born 1926). He published his first work, ''Guilt and Morality'', which is devoted to the trial of Hilda Haniková, who hired a murderer to kill her own husband. He had already joined the Social Democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

in KroměřĂĹľ before World War I. After its split in 1921, he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Com ...

, for which he was elected to the Brno city council. However, he disagreed with the gradual Bolshevization of the party and its subservience to the Soviet leadership, for which he was expelled from the party in 1929. He first worked in the Communist opposition, then returned to the Social Democrats, for whom he became second deputy mayor of Brno in 1935.

EÄŤer actively opposed the rising German Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

, which he recognized as a major danger for the future, and became, for example, a member of the Committee for the Relief of Democratic Spain. In 1938, he publicly agitated for Czechoslovakia's readiness to defend itself against the threat of Nazi Germany, and lectured and persuaded public officials in England, which brought him to the attention of the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

.

After the occupation

After the occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia, he emigrated with his family viaZagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

and Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, where he participated in the Czechoslovak National Committee

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repub ...

. There he also wrote a thesis ''The Occupation of Bohemia and Moravia and the Establishment of the "Protectorate" in the Light of International Law'', which, however, was not published due to the German attack. After the fall of France, they went to Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-RhĂ´ne and of the Provence-Alpes-CĂ´te d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, where the Czechoslovak consulate was still functioning, but they were deemed undesirable by the Vichist government and so they moved to Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionCzechoslovak Government in Exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile, sometimes styled officially as the Provisional Government of Czechoslovakia (; ), was an informal title conferred upon the Czechoslovak National Liberation Committee (; ), initially by British diplomatic rec ...

, and later was an associate of the Minister of Justice Jaroslav Stránský.

EÄŤer had long been involved in issues of international criminal law, war law and war crimes, hence his membership of the London International Assembly's War Crimes Commission, He also wrote the booklet ''The Lessons of the Kharkov Trial''. He was delegated by the government-in-exile as Czechoslovakia's representative to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

War Crimes Commission, where he eventually successfully pushed for the declaration of United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

as an international crime.

Role in the Nuremberg Trials

He played a significant role in the establishment of theInternational Military Tribunal

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

for the punishment of war criminals, which sat in Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

after the war and in which Bohuslav EÄŤer participated as chairman of the Czechoslovak delegation. Prior to that, he was the head of the Czechoslovak investigative team that found Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank (24 January 1898 – 22 May 1946) was a Sudeten Germans, Sudeten German Nazism, Nazi official in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia prior to and during World War II. Attaining the rank of ''Obergruppenführer'', he was in ...

in Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden (; ) is the capital of the German state of Hesse, and the second-largest Hessian city after Frankfurt am Main. With around 283,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 24th-largest city. Wiesbaden form ...

. EÄŤer was the first to interrogate him, and as a general of the judicial service, he also retrieved him from American captivity into the hands of Czechoslovak justice. He told him at the outset, "I have not used and will not use your methods. You need not be afraid of them. We are not Germans, we do not take revenge. We will only punish."

In addition to him, he also interviewed e.g. Reich Protector Kurt Daluege

Kurt Max Franz Daluege (15 September 1897 – 24 October 1946) was a German ''SS-Oberst-Gruppenführer'' and ''Generaloberst'' of the police, the highest ranking police officer, who served as chief of ''Ordnungspolizei'' (Order Police) of N ...

, Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Germany), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945. ...

, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal who held office as chief of the (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's armed forces, during World War II. He signed a number of criminal ...

, SS General Bernhard Voss and Reich Minister and Reich Chancellery Chief Hans Lammers

Hans Heinrich Lammers (27 May 1879 – 4 January 1962) was a German jurist and prominent Nazi Party politician. From 1933 until 1945 he served as Chief of the Reich Chancellery under Adolf Hitler. In 1937, he additionally was given the post of ' ...

. After the Nuremberg Trials, he served as a judge of the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

, where he ruled in the so-called " Corfu Strait Incident" between Great Britain and Albania, dissenting from the majority decision on Albania's responsibility. He described his experiences throughout this period in the popular books ''The Nuremberg Trial'', ''How I Prosecuted Them'', ''Law in the Struggle with Nazism'' and ''Lessons from the Nuremberg Trial for the Slavs''.

Post-war years

In 1948, he became firstassociate professor

Associate professor is an academic title with two principal meanings: in the North American system and that of the ''Commonwealth system''.

In the ''North American system'', used in the United States and many other countries, it is a position ...

and then professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other tertiary education, post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin ...

of international criminal law at the Faculty of Law of Masaryk University in Brno, where he headed the Institute for International Criminal Law and published the script ''Handbook of Public International Law''. He also published a scientific monograph ''Development and Foundations of International Criminal Law''. However, he did not stay there for long, as the faculty was closed down in 1950. Although Bohuslav Ečer remained in the university, he could not teach or publish. As a former social democrat who had taken part in the war resistance in the West and who, among other things, had defended Milada Horáková

Milada Horáková (born: Králová, 25 December 1901 – 27 June 1950) was a Czech politician and a member of the underground resistance movement during World War II. She was a victim of judicial murder, convicted and executed by the Communis ...

, he gradually became a target of StB

State Security (, ), or StB / Ĺ tB, was the secret police force in communist Czechoslovakia from 1945 to its dissolution in 1990. Serving as an intelligence and counter-intelligence agency, it dealt with any activity that was considered oppositio ...

. However, when they came to arrest him in 1954, as he was to be one of the defendants in the upcoming mock trial of the so-called Brno Group, he was already a day dead. He died a quick death from a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

of the left posterior chamber of his heart. His wife Ludmila escaped persecution by hiding in a psychiatric hospital, but his daughter Jarmila was sentenced to 12 years and released after Amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

in 1960.

Awards

In 2001, Bohuslav EÄŤer was awarded the ''in memoriam''

In 2001, Bohuslav EÄŤer was awarded the ''in memoriam'' honorary citizenship

Honorary citizenship is a status bestowed by a city or other government on a foreign or native individual whom it considers to be especially admirable or otherwise worthy of the distinction. The honor usually is symbolic and does not confer an ...

of the city of Brno and in Brno-Bystrc

Bystrc ( Hantec: Bástr) is a city district of Brno in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the sou ...

a street named after him, EÄŤerova Street.

In 2012, he was awarded the Václav Benda Prize (''in memoriam''). In 2019, President Miloš Zeman

Miloš Zeman (; born 28 September 1944) is a Czech politician who served as the third president of the Czech Republic from 2013 to 2023. He also previously served as the prime minister of the Czech Republic from 1998 to 2002. As leader of the Cze ...

conferred on him ''in memoriam'' the Order of the White Lion

The Order of the White Lion () is the highest order of the Czech Republic. It continues a Czechoslovak order of the same name created in 1922 as an award for foreigners (Czechoslovakia having no civilian decoration for its citizens in the 192 ...

of the Military Group, First Class.

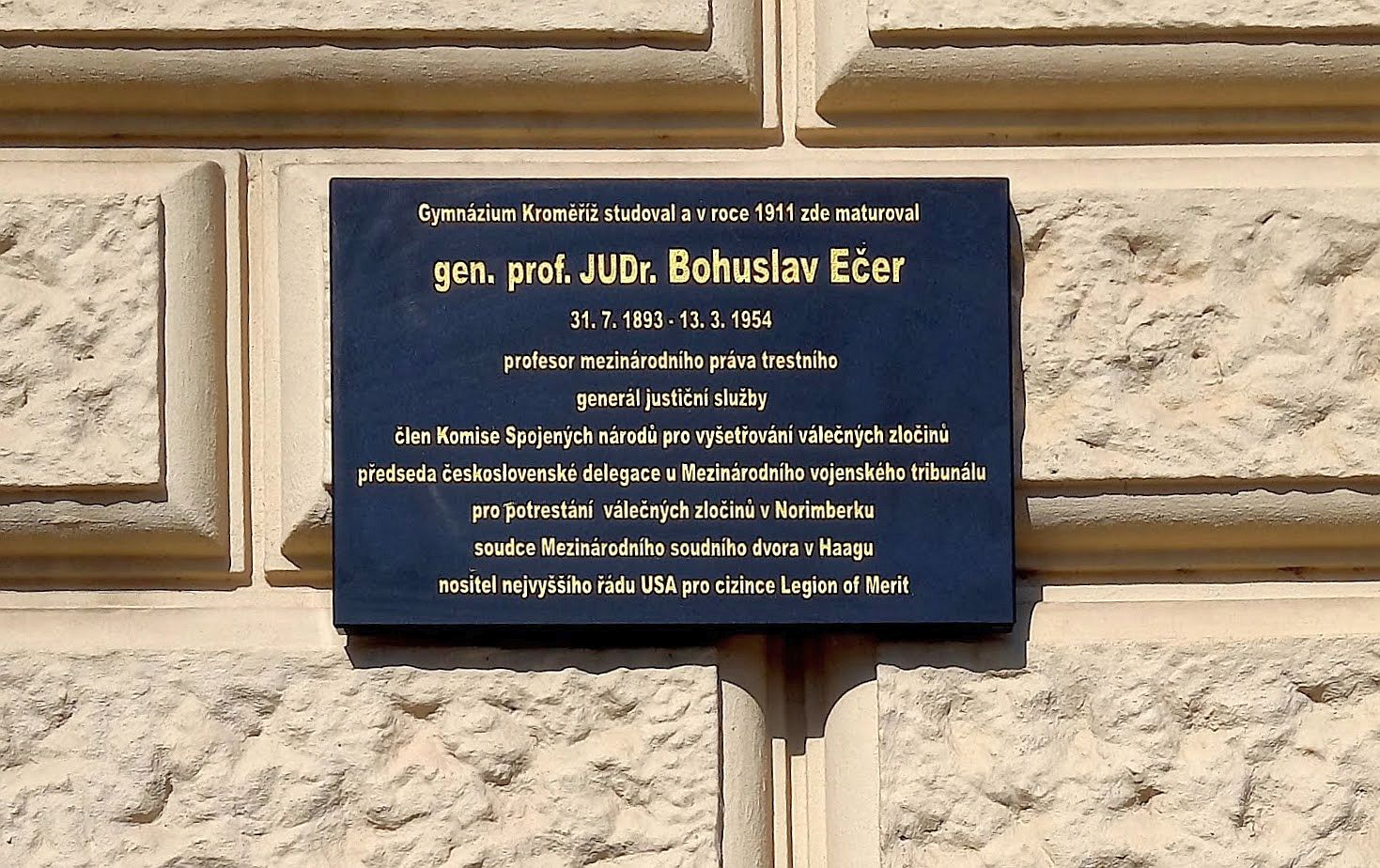

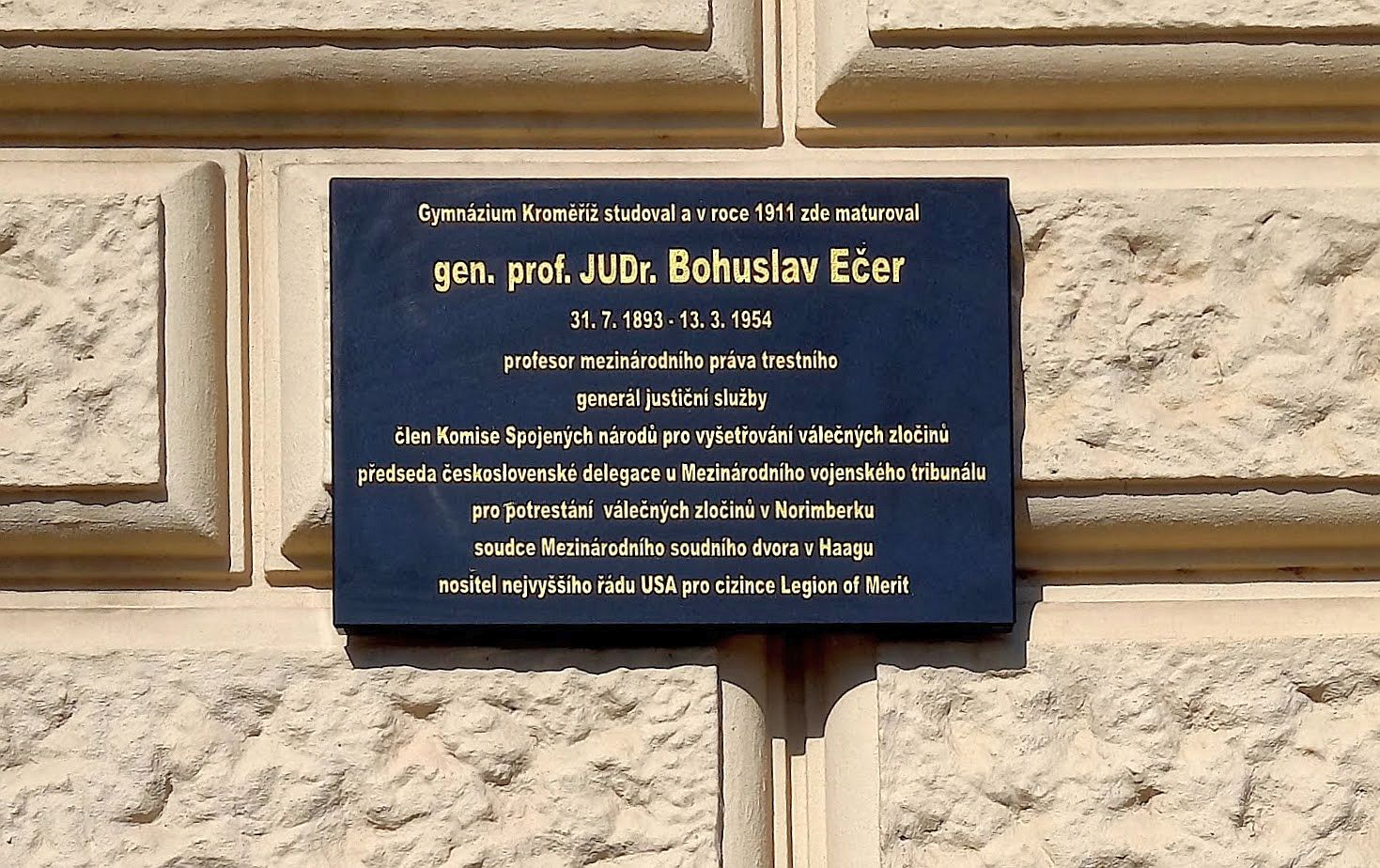

On 1 October 2021, a memorial plaque

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, bearing text or an image in relief, or both, ...

was unveiled on the gymnasium building in KroměřĂĹľ.

References

1893 births 1954 deaths People from Hranice (Přerov District) Czechoslovak generals {{Improve categories, date=March 2024