Blériot 110 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

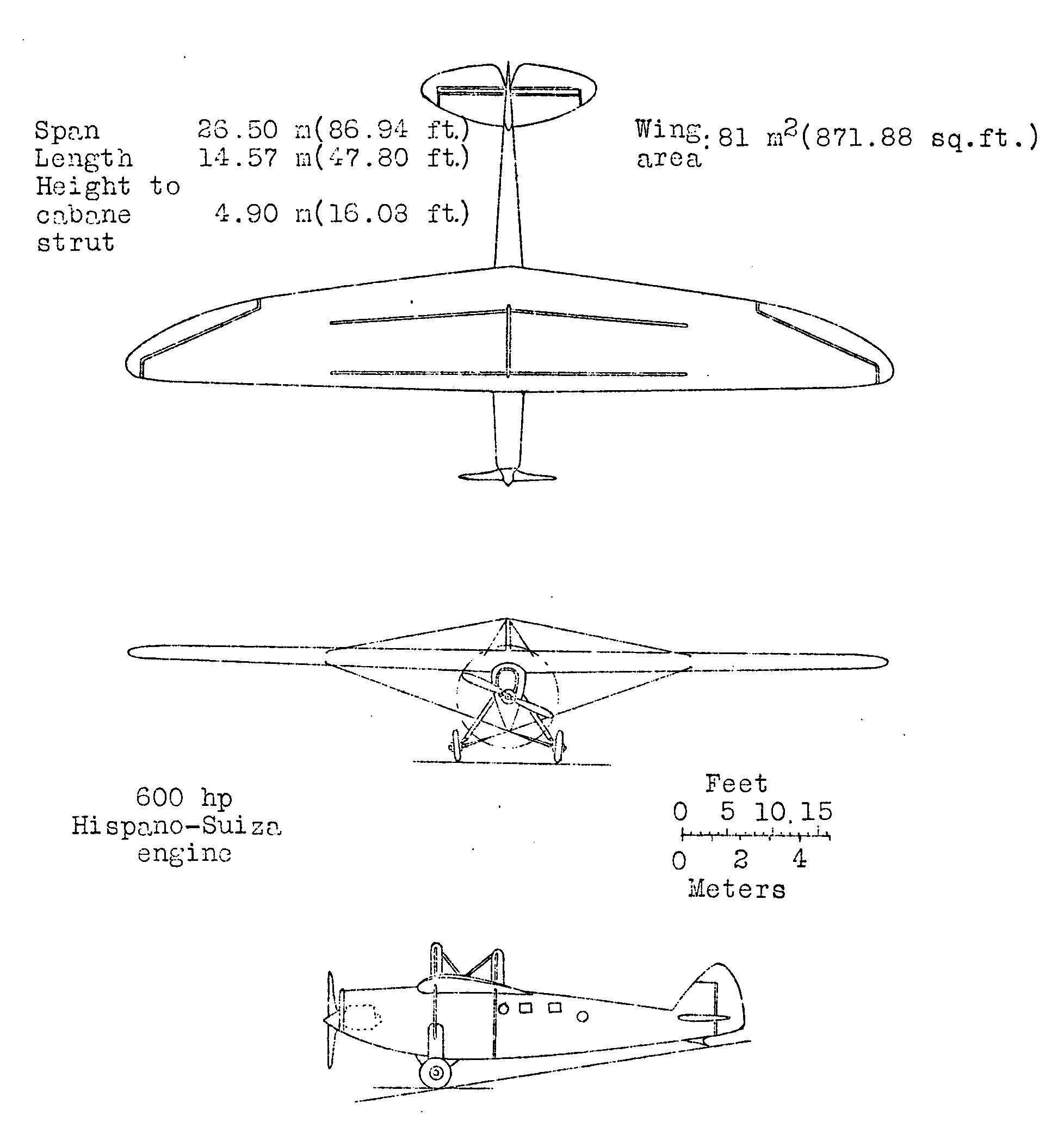

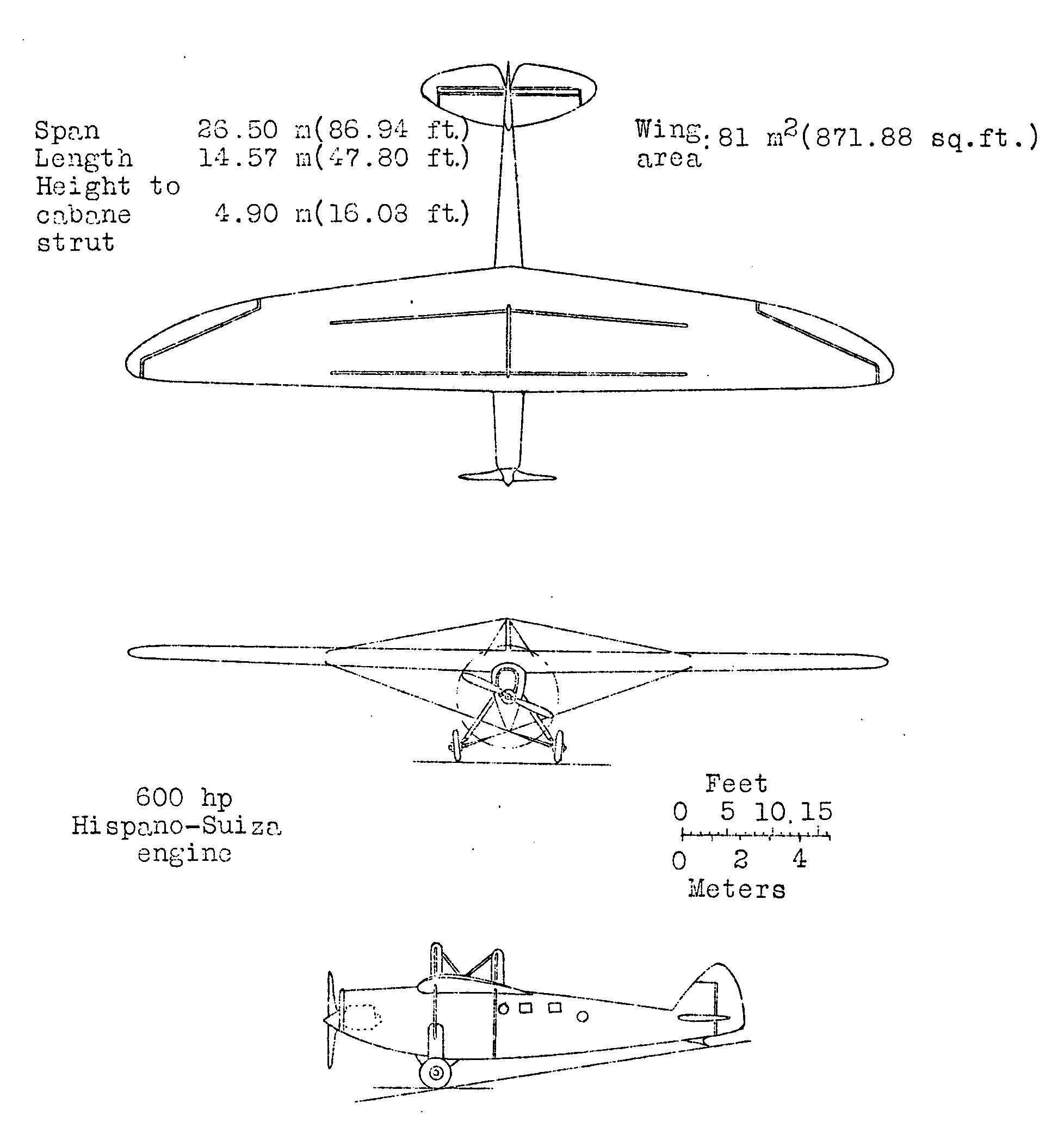

The Blériot 110 (or Blériot-Zappata 110) was a high-endurance research aircraft designed and produced by the French aircraft manufacturer

''Popular Mechanic'', December 1933, p. 807. The undercarriage, which was

"The Bleriot 110 airplane (French) : a long-distance high-wing monoplane"

''

Blériot Aéronautique

Blériot Aéronautique was a French aircraft manufacturer founded by Louis Blériot. It also made a few motorcycles between 1921 and 1922 and cyclecars during the 1920s.

Background

Louis Blériot was an engineer who had developed the first practi ...

. It was specifically developed to pursue new world records pertaining to long distance flights.

Design and development

The Blériot 110 was developed specifically at the request of the ordered by the Service Technique of the French Air Ministry. Blériot Aéronautique, who opted to respond, designed a twin-seat high-wingmonoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple wings.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing con ...

that was primarily constructed of wood. ''Flight'' 31 March 1931, p. 219. https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1931/1931%20-%200235.html The resulting aircraft exhibited a high degree of both fineness and lightness.NACA 1931, p. 1.

In terms of its basic configuration, the Blériot 110 comprised a fuselage with a heart-shaped cross section and a proportionally large wing. The fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

had a high degree of fineness due to the narrowness of its principal section, which consequentially reduced the unutilised lower surface area of the wing. During testing, this shape was revealed to possess excellent penetration characteristics, in part due to the junction being positioned almost at a right angle, in comparison to the acute angles (and the resulting interference) that some alternative configurations would have involved. The frontal area of the fuselage was restricted to that deemed to be strictly necessary to accommodate the honeycomb

A honeycomb is a mass of Triangular prismatic honeycomb#Hexagonal prismatic honeycomb, hexagonal prismatic cells built from beeswax by honey bees in their beehive, nests to contain their brood (eggs, larvae, and pupae) and stores of honey and pol ...

radiator

A radiator is a heat exchanger used to transfer thermal energy from one medium to another for the purpose of cooling and heating. The majority of radiators are constructed to function in cars, buildings, and electronics.

A radiator is always a ...

. While superior aerodynamic performance could have been achieved with a radiator that was mounted either on the sides of the fuselage or the wing, it was determined that those alternative arrangements were too immature to endure the continuous vibrations they'd be exposed to during high endurance flights. In terms of height, the fuselage was somewhat elongated and terminated at a single point at its base; this shape, via the combination of a cabane and a series of bracing wires (which weighed only 90kg/198lb), a relatively light wing with a large aspect ratio

The aspect ratio of a geometry, geometric shape is the ratio of its sizes in different dimensions. For example, the aspect ratio of a rectangle is the ratio of its longer side to its shorter side—the ratio of width to height, when the rectangl ...

.NACA 1931, pp. 1-2.

All together, the fineness of the aircraft was 17 when the wheels were cowled; it could reportedly be increased to nearly 19.5 by eliminating the undercarriage

Undercarriage is the part of a moving vehicle that is underneath the main body of the vehicle. The term originally applied to this part of a horse-drawn carriage, and usage has since broadened to include:

*The landing gear of an aircraft.

*The ch ...

. Alternative models, including a rectangular and an elliptical configuration, were studied. The propeller was lowered as much as was practical to be done, which brought the slipstream

A slipstream is a region behind a moving object in which a wake of fluid (typically air or water) is moving at velocities comparable to that of the moving object, relative to the ambient fluid through which the object is moving. The term slips ...

beneath the wing; the distance between the propeller and the leading edge

The leading edge is the part of the wing that first contacts the air;Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', page 305. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. alternatively it is the foremost edge of an airfoil sectio ...

of the wing was only four meters (13.12 ft). The structure of the fuselage comprised a ventral keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

and a pair of upper longeron

In engineering, a longeron or stringer is a load-bearing component of a framework.

The term is commonly used in connection with aircraft fuselages and automobile chassis. Longerons are used in conjunction with stringers to form structural fram ...

s; the transverse structure comprised a series of bulkheads and intermediate frames; the spaces between these objects were occupied by formers. The fuselage covering was load-bearing, consisting of three layers of whitewood strips that were both glued and nailed to the framework along with a fabric

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, and different types of fabric. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is no ...

covering; the exterior was fairly smooth, resistant to torsion

Torsion may refer to:

Science

* Torsion (mechanics), the twisting of an object due to an applied torque

* Torsion of spacetime, the field used in Einstein–Cartan theory and

** Alternatives to general relativity

* Torsion angle, in chemistry

Bio ...

, and exhibited none of the bulging common to plywood

Plywood is a composite material manufactured from thin layers, or "plies", of wood veneer that have been stacked and glued together. It is an engineered wood from the family of manufactured boards, which include plywood, medium-density fibreboa ...

construction.NACA 1931, pp. 3-4.

The wing was manufactured in three parts, an arrangement that permitted it to be readily transported along the public road network, the benefits of which was seen as advantageous enough to offset the minor weight increase over a single piece counterpart.NACA 1931, pp. 2-3. The twin spars of the wing were connected via an oblique aileron

An aileron (French for "little wing" or "fin") is a hinged flight control surface usually forming part of the trailing edge of each wing of a fixed-wing aircraft. Ailerons are used in pairs to control the aircraft in roll (or movement aroun ...

supporting spar; this arrangement permitted stresses to be conveyed between the forward and rear spars and thus permitted a lighter structure than would have otherwise been possible without such a connection being present. Furthermore, the aileron-supporting spar, which was securely attached at three separate points, also considerably bolstered the torsional resistance while also being much lighter than a traditional spar that would have been secured only at one end.NACA 1931, p. 3. It was reported that the total weight of the wing was roughly 50 percent of what a cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is unsupported at one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a cantilev ...

counterpart would have had with the same aspect ratio.NACA 1931, p. 2.

Both of the pilots' positions were enclosed within the fuselage; as means of addressing the restrictive external visibility that this arrangement incurred, porthole

A porthole, sometimes called bull's-eye window or bull's-eye, is a generally circular window used on the hull of ships to admit light and air. Though the term is of maritime origin, it is also used to describe round windows on armored vehic ...

s were present to give the pilots some degree of lateral visibility while a forward view was obtainable using a periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

, the latter being particularly critical during take-offs and landings.NACA 1931, p. 4. The cockpit was provisioned with various controls and instrumentation, which included a pitch indicator, altimeter

An altimeter or an altitude meter is an instrument used to measure the altitude of an object above a fixed level. The measurement of altitude is called altimetry, which is related to the term bathymetry, the measurement of depth under water.

Ty ...

, two tachometer

A tachometer (revolution-counter, tach, rev-counter, RPM gauge) is an instrument measuring the rotation speed of a axle, shaft or disk, as in a motor or other machine. The device usually displays the revolutions per minute (RPM) on a calibrat ...

s, multiple fuel gauges, inlet and outlet oil thermometers, ignition advance, dumping control, fuel cocks, fire alarm, carburetor

A carburetor (also spelled carburettor or carburetter)

is a device used by a gasoline internal combustion engine to control and mix air and fuel entering the engine. The primary method of adding fuel to the intake air is through the Ventu ...

heater, clock, map holder, and a wheel to adjust the stabiliser amongst others. Safety measures included provisions for the use of fire extinguisher

A fire extinguisher is a handheld active fire protection device usually filled with a dry or wet chemical used to extinguish or control small fires, often in emergencies. It is not intended for use on an out-of-control fire, such as one which ha ...

s and parachute

A parachute is a device designed to slow an object's descent through an atmosphere by creating Drag (physics), drag or aerodynamic Lift (force), lift. It is primarily used to safely support people exiting aircraft at height, but also serves va ...

s.NACA 1931, pp. 4-5.

The aircraft was outfitted with six fuel tanks in the wings and four in the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

, holding a combined total of 6,000 L (1,319 Imperial gallon

The gallon is a unit of measurement, unit of volume in British imperial units and United States customary units.

The imperial gallon (imp gal) is defined as , and is or was used in the United Kingdom and its former colonies, including Ireland ...

s or 1,585 US gal); these tanks were located forwards of the pilot and co-pilot positions. Each tank was supported by a duralumin structure and connected to bracing wires at its base; their weight was only three percent of that of a full fuel loadout.NACA 1931, p. 8. A sleeping couch was fitted behind the co-pilot's station so one of the crew members could sleep on long-distance flights."Mirrors Help Record Ship Take-Off and Land."''Popular Mechanic'', December 1933, p. 807. The undercarriage, which was

streamlined

Streamlines, streaklines and pathlines are field lines in a fluid flow.

They differ only when the flow changes with time, that is, when the flow is not steady flow, steady.

Considering a velocity vector field in three-dimensional space in the f ...

, was furnished with shock-absorbing struts, which comprised telescoping tubes that were interconnected via crosspieces that bore elastic cables.NACA 1931, p. 5. The tail unit featured a fin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. F ...

that was formed from a continuation of upright members of the fuselage; its leading edge was covered with plywood while its trailing edge had a fabric covering. The rear spar of the stabilizer and the front spar of the elevator

An elevator (American English) or lift (Commonwealth English) is a machine that vertically transports people or freight between levels. They are typically powered by electric motors that drive traction cables and counterweight systems suc ...

were hinged to a central piece. The stabilizer could be adjusted mid-flight.NACA 1931, p. 6.

It was powered by a single Hispano-Suiza 12L

Hispano-Suiza () is a Spanish automotive company. It was founded in 1904 by Marc Birkigt and as an automobile manufacturer and eventually had several factories in Spain and France that produced luxury cars, aircraft engines, trucks and weapons ...

piston engine that directly drove the aircraft's propeller; Blériot decided against the use of reduction gear due to the suboptimal gearing available for an aircraft intended for such flights. The powerplant was carried upon an engine hearer that was composed of duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age hardening, age-hardenable aluminium–copper alloys. The term is a combination of ''Düren'' and ''aluminium'' ...

and incorporated relatively cutting edge principles. Separate elements were present to withstand the forces of gravity and traction, and torque; both gravity and traction were absorbed by a rigid triangularly-braced hinged girder

A girder () is a Beam (structure), beam used in construction. It is the main horizontal support of a structure which supports smaller beams. Girders often have an I-beam cross section composed of two load-bearing ''flanges'' separated by a sta ...

while torque was absorbed by the duralumin covering, which was riveted to multiple girders without undermining the elasticity or the stress-absorption properties, of the hinged element. The forward bulkhead was a metal frame to which the stresses were communicated at five points, four in the plane of the engine-bearer longerons while the final was at the point of attachment to the keel; these stresses were transmitted to the bulkhead situated in the vicinity of the forward wing spar.NACA 1931, p. 7.

Operational history

On 16 May 1930, the aircraft conducted itsmaiden flight

The maiden flight, also known as first flight, of an aircraft is the first occasion on which it leaves the ground under its own power. The same term is also used for the first launch of rockets.

In the early days of aviation it could be dange ...

; however, this was cut short by a fuel supply issue, although no damage was sustained. Following repairs, it was transported to Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

, Algeria, where it made an attempt on the closed-circuit distance record. Between 15 November and 26 March 1932, the Blériot 110, flown by Lucien Bossoutrot

Lucien is a male given name. It is the French form of Luciano or Latin ''Lucianus'', patronymic of Lucius.

People

Given name

*Lucien, 3rd Prince Murat (1803–1878), French politician and Prince of Pontecorvo

*Lucien, Lord of Monaco (1487–1 ...

and Maurice Rossi

Maurice may refer to:

*Maurice (name), a given name and surname, including a list of people with the name

Places

* or Mauritius, an island country in the Indian Ocean

*Maurice, Iowa, a city

*Maurice, Louisiana, a village

*Maurice River, a trib ...

, broke this record three times; on the final occasion staying aloft for 76 hours and 34 minutes and covering a distance of . By this time, the aircraft had been named '' Joseph Le Brix'' in honour of the pilot who had died flying the Blériot 110's principal rival, the Dewoitine D.33.

On 5 August 1933, Paul Codos

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo P ...

and Maurice Rossi set a new straight-line distance record, flying from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

to Rayak

Rayaq - Haouch Hala (), also romanization of Arabic, romanized Rayak, is a Lebanon, Lebanese town in the Beqaa Governorate, Beqaa Mohafazat, Governorate near the city of Zahlé. In the early 20th century and up to the 1975 outbreak of the Lebane ...

, Lebanon – a distance of . Further records were attempted over the next two years, but these were proved unsuccessful, and the 110 was scrapped.

Specifications

See also

References

Citations

Bibliography

* *"The Bleriot 110 airplane (French) : a long-distance high-wing monoplane"

''

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency that was founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its ...

'', 1 March 1931. NACA-AC-138, 93R19716.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bleriot 110

High-wing aircraft

Single-engined tractor aircraft

1930s French experimental aircraft

110

110 may refer to:

*110 (number), natural number

*AD 110, a year

*110 BC, a year

*110 film, a cartridge-based film format used in still photography

* 110 (MBTA bus), Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority bus route

*110 (song), 2019 song by Cap ...

Aircraft first flown in 1930

Aircraft with fixed conventional landing gear