Blood Bank on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A blood bank is a center where

Robertson published his findings in the ''

Robertson published his findings in the ''

The world's first blood donor service was established in 1921 by the secretary of the

The world's first blood donor service was established in 1921 by the secretary of the  One of the earliest blood banks was established by Frederic Durán-Jordà during the

One of the earliest blood banks was established by Frederic Durán-Jordà during the

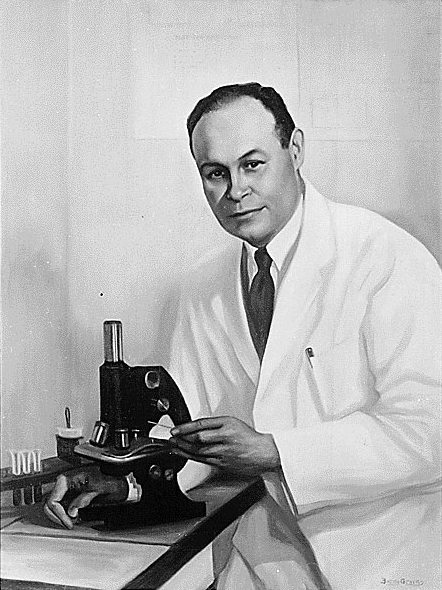

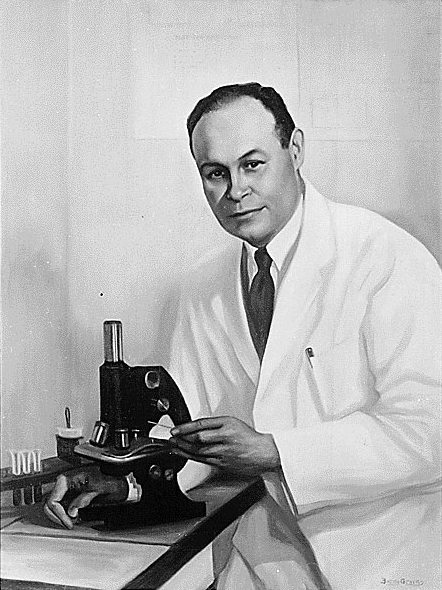

The resulting dried plasma package came in two tin cans containing 400 cc bottles. One bottle contained enough distilled water to reconstitute the dried plasma contained within the other bottle. In about three minutes, the plasma would be ready to use and could stay fresh for around four hours. Charles R. Drew was appointed medical supervisor, and he was able to transform the

The resulting dried plasma package came in two tin cans containing 400 cc bottles. One bottle contained enough distilled water to reconstitute the dried plasma contained within the other bottle. In about three minutes, the plasma would be ready to use and could stay fresh for around four hours. Charles R. Drew was appointed medical supervisor, and he was able to transform the

In the U.S., certain standards are set for the collection and processing of each blood product. "Whole blood" (WB) is the proper name for one defined product, specifically unseparated venous blood with an approved preservative added. Most blood for transfusion is collected as whole blood. Autologous donations are sometimes transfused without further modification, however whole blood is typically separated (via centrifugation) into its components, with

In the U.S., certain standards are set for the collection and processing of each blood product. "Whole blood" (WB) is the proper name for one defined product, specifically unseparated venous blood with an approved preservative added. Most blood for transfusion is collected as whole blood. Autologous donations are sometimes transfused without further modification, however whole blood is typically separated (via centrifugation) into its components, with

Animated Venipuncture tutorial

{{DEFAULTSORT:Blood Bank Transfusion medicine Blood donation

blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

gathered as a result of blood donation

A 'blood donation'' occurs when a person voluntarily has blood drawn and used for transfusions and/or made into biopharmaceutical medications by a process called fractionation (separation of whole blood components). A donation may be of wh ...

is stored and preserved for later use in blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's Circulatory system, circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used ...

. The term "blood bank" typically refers to a department of a hospital usually within a clinical pathology

Clinical pathology is a medical specialty that is concerned with the diagnosis of disease based on the laboratory analysis of bodily fluids, such as blood, urine, and tissue homogenates or extracts using the tools of chemistry, microbiology, ...

laboratory

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratories are found in a variety of settings such as schools ...

where the storage of blood product occurs and where pre-transfusion and blood compatibility testing is performed. However, it sometimes refers to a collection center, and some hospitals also perform collection. Blood banking includes tasks related to blood collection, processing, testing, separation, and storage.

For blood donation agencies in various countries, see list of blood donation agencies and list of blood donation agencies in the United States

Nearly every hospital in the United States has a blood bank and transfusion service. The following is a list of groups that collect blood for transfusion and not a complete list of blood banks.

National organizations

* American Red Cross (ARC), ...

.

Types of blood transfused

Several types of blood transfusion exist: * Whole blood, which is blood transfused without separation. * Red blood cells or packed cells is transfused to patients with anemia/iron deficiency. It also helps to improve the oxygen saturation in blood. It can be stored at 2.0 °C-6.0 °C for 35–45 days. *Platelet transfusion

Platelet transfusion, is the process of infusing platelet concentrate into the body via vein, to prevent or treat the bleeding in people with either a thrombocytopenia, low platelet count or poor platelet function. Often this occurs in people ...

is transfused to those with low platelet count. Platelets can be stored at room temperature for up to 5–7 days. Single donor platelets, which have a more platelet count but it is bit expensive than regular.

* Plasma transfusion is indicated to patients with liver failure, severe infections or serious burns. Fresh frozen plasma

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is a blood product made from the liquid portion of whole blood. It is used to treat conditions in which there are low blood clotting factors (INR > 1.5) or low levels of other blood proteins. It may also be used as the r ...

can be stored at a very low temperature of -30 °C for up to 12 months. The separation of plasma from a donor's blood is called plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis (from the Greek language, Greek πλάσμα, ''plasma'', something molded, and ἀφαίρεσις ''aphairesis'', taking away) is the removal, treatment, and return or exchange of blood plasma or components thereof from and to the ...

.

History

While the firstblood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's Circulatory system, circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used ...

s were made directly from donor to receiver before coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a thrombus, blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of co ...

, it was discovered that by adding anticoagulant

An anticoagulant, commonly known as a blood thinner, is a chemical substance that prevents or reduces the coagulation of blood, prolonging the clotting time. Some occur naturally in blood-eating animals, such as leeches and mosquitoes, which ...

and refrigerating the blood it was possible to store it for some days, thus opening the way for the development of blood banks. John Braxton Hicks was the first to experiment with chemical methods to prevent the coagulation of blood at St Mary's Hospital, London

St Mary's Hospital is a teaching hospital in Paddington, in the City of Westminster, London, founded in 1845. Since the UK's first academic health science centre was created in 2008, it has been operated by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust ...

, in the late 19th century. His attempts, using phosphate of soda, however, were unsuccessful.

The first non-direct transfusion was performed on March 27, 1914, by the Belgian doctor Albert Hustin, though this was a diluted solution of blood. The Argentine

Argentines, Argentinians or Argentineans are people from Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultural. For most Argentines, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their ...

doctor Luis Agote used a much less diluted solution in November of the same year. Both used sodium citrate as an anticoagulant.

First World War

TheFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

acted as a catalyst for the rapid development of blood banks and transfusion techniques. Inspired by the need to give blood to wounded soldiers in the absence of a donor, Francis Peyton Rous at the Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a Private university, private Medical research, biomedical Research university, research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and pro ...

(then The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research) wanted to solve the problems of blood transfusion. With a colleague, Joseph R. Turner, he made two critical discoveries: blood typing was necessary to avoid blood clumping (coagulation) and blood samples could be preserved using chemical treatment. Their report in March 1915 to identify possible blood preservative was of a failure. The experiments with gelatine, agar, blood serum extracts, starch and beef albumin proved useless.

In June 1915, they made the first important report in the ''Journal of the American Medical Association

''JAMA'' (''The Journal of the American Medical Association'') is a peer-reviewed medical journal published 48 times a year by the American Medical Association. It publishes original research, reviews, and editorials covering all aspects of ...

'' that agglutination could be avoided if the blood samples of the donor and recipient were tested before. They developed a rapid and simple method for testing blood compatibility in which coagulation and the suitability of the blood for transfusion could be easily determined. They used sodium citrate to dilute the blood samples, and after mixing the recipient's and donor's blood in 9:1 and 1:1 parts, blood would either clump or remain watery after 15 minutes. Their result with a medical advice was clear:fclumping is present in the 9:1 mixture and to a less degree or not at all in the 1:1 mixture, it is certain that the blood of the patient agglutinates that of the donor and may perhaps hemolyze it. Transfusion in such cases is dangerous. Clumping in the 1:1 mixture with little or none in the 9:1 indicates that the plasma of the prospective donor agglutinates the cells of the prospective recipient. The risk from transfusing is much less under such circumstances, but it may be doubted whether the blood is as useful as one which does not and is not agglutinated. A blood of the latter kind should always be chosen if possible.Rous was well aware that Austrian physician

Karl Landsteiner

Karl Landsteiner (; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He emigrated with his family to New York in 1923 at the age of 55 for professional opportunities, working for the Rockefeller ...

had discovered blood types a decade earlier, but the practical usage was not yet developed, as he described: "The fate of Landsteiner's effort to call attention to the practical bearing of the group differences in human bloods provides an exquisite instance of knowledge marking time on technique. Transfusion was still not done because (until at least 1915), the risk of clotting was too great." In February 1916, they reported in the ''Journal of Experimental Medicine

''Journal of Experimental Medicine'' is a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal published by Rockefeller University Press that publishes research papers and commentaries on the physiological, pathological, and molecular mechanisms that encompass ...

'' the key method for blood preservation. They replaced the additive, gelatine, with a mixture sodium citrate and glucose (dextrose

Glucose is a sugar with the molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water an ...

) solution and found: "in a mixture of 3 parts of human blood, 2 parts of isotonic citrate solution (3.8 per cent sodium citrate in water), and 5 parts of isotonic dextrose solution (5.4 per cent dextrose in water), the cells remain intact for about 4 weeks." A separate report indicates the use of citrate-saccharose (sucrose) could maintain blood cells for two weeks. They noticed that the preserved bloods were just like fresh bloods and that they "function excellently when reintroduced into the body." The use of sodium citrate with sugar, sometimes known as Rous-Turner solution, was the main discovery that paved the way for the development of various blood preservation methods and blood bank.

Canadian Lieutenant Lawrence Bruce Robertson was instrumental in persuading the Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was a specialist corps in the British Army which provided medical services to all Army personnel and their families, in war and in peace.

On 15 November 2024, the corps was amalgamated with the Royal Army De ...

(RAMC) to adopt the use of blood transfusion at the Casualty Clearing Stations for the wounded. In October 1915, Robertson performed his first wartime transfusion with a syringe to a patient who had multiple shrapnel wounds. He followed this up with four subsequent transfusions in the following months, and his success was reported to Sir Walter Morley Fletcher, director of the Medical Research Committee.

Robertson published his findings in the ''

Robertson published his findings in the ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a fortnightly peer-reviewed medical journal, published by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, which in turn is wholly-owned by the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world ...

'' in 1916, and—with the help of a few like minded individuals (including the eminent physician Edward William Archibald

Edward William Archibald (August 5, 1872 – December 17, 1945) was a Canadian surgeon. Archibald was born in Montreal, Quebec, and received his initial education in Grenoble, France. Upon returning to Canada, he attended McGill University, r ...

)—was able to persuade the British authorities of the merits of blood transfusion. Robertson went on to establish the first blood transfusion apparatus at a Casualty Clearing Station on the Western Front in the spring of 1917.

Oswald Hope Robertson, a medical researcher and officer, worked with Rous at the Rockefeller between 1915 and 1917, and learned the blood matching and preservation methods. He was attached to the RAMC in 1917, where he was instrumental in establishing the first blood banks, with soldiers as donors, in preparation for the anticipated Third Battle of Ypres. He used sodium citrate as the anticoagulant, and the blood was extracted from punctures in the vein, and was stored in bottles at British and American Casualty Clearing Stations along the Front. He also experimented with preserving separated red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s in iced bottles. Geoffrey Keynes, a British surgeon, developed a portable machine that could store blood to enable transfusions to be carried out more easily.

Expansion

The world's first blood donor service was established in 1921 by the secretary of the

The world's first blood donor service was established in 1921 by the secretary of the British Red Cross

The British Red Cross Society () is the United Kingdom body of the worldwide neutral and impartial humanitarian network the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. The society was formed in 1870, and is a registered charity with 1 ...

, Percy Lane Oliver. Volunteers were subjected to a series of physical tests to establish their blood group. The London Blood Transfusion Service was free of charge and expanded rapidly. By 1925, it was providing services for almost 500 patients and it was incorporated into the structure of the British Red Cross in 1926. Similar systems were established in other cities including Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

, Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

and Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, and the service's work began to attract international attention. Similar services were established in France, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Australia and Japan.

Vladimir Shamov and Sergei Yudin in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

pioneered the transfusion of cadaveric blood from recently deceased donors. Yudin performed such a transfusion successfully for the first time on March 23, 1930, and reported his first seven clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambulatory care clinic) is a health facility that is primarily focused on the care of outpatients. Clinics can be privately operated or publicly managed and funded. They typically cover the primary care needs ...

al transfusions with cadaveric blood at the Fourth Congress of Ukrainian Surgeons at Kharkiv in September. Also in 1930, Yudin organized the world's first blood bank at the Nikolay Sklifosovsky Institute, which set an example for the establishment of further blood banks in different regions of the Soviet Union and in other countries. By the mid-1930s the Soviet Union had set up a system of at least 65 large blood centers and more than 500 subsidiary ones, all storing "canned" blood and shipping it to all corners of the country.

One of the earliest blood banks was established by Frederic Durán-Jordà during the

One of the earliest blood banks was established by Frederic Durán-Jordà during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

in 1936. Duran joined the Transfusion Service at the Barcelona Hospital at the start of the conflict, but the hospital was soon overwhelmed by the demand for blood and the paucity of available donors. With support from the Department of Health of the Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army () was the main branch of the Spanish Republican Armed Forces, Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la República'' ...

, Duran established a blood bank for the use of wounded soldiers and civilians. The 300–400 ml of extracted blood was mixed with 10% citrate solution in a modified Duran Erlenmeyer flask. The blood was stored in a sterile glass enclosed under pressure at 2 °C. During 30 months of work, the Transfusion Service of Barcelona registered almost 30,000 donors, and processed 9,000 liters of blood.

In 1937 Bernard Fantus

Bernard Fantus (September 1, 1874 – April 14, 1940) was a Hungarian Jewish-American physician. He established the first hospital blood bank in the United States in 1937 at Cook County Hospital, Chicago while he served there as director of the ph ...

, director of therapeutics at the Cook County Hospital

The John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County (shortened ''Stroger Hospital'', formerly Cook County Hospital) is a public hospital in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It is part of Cook County Health, along with Provident Hospital of Cook Cou ...

in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, established one of the first hospital blood banks in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. In creating a hospital laboratory that preserved, refrigerated and stored donor blood, Fantus originated the term "blood bank". Within a few years, hospital and community blood banks were established across the United States.

Frederic Durán-Jordà fled to Britain in 1938, and worked with Janet Vaughan at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School at Hammersmith Hospital to create a system of national blood banks in London. With the outbreak of war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

looking imminent in 1938, the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

created the Army Blood Supply Depot (ABSD) in Bristol headed by Lionel Whitby and in control of four large blood depots around the country. British policy through the war was to supply military personnel with blood from centralized depots, in contrast to the approach taken by the Americans and Germans where troops at the front were bled to provide required blood. The British method proved to be more successful at adequately meeting all requirements and over 700,000 donors were bled over the course of the war. This system evolved into the National Blood Transfusion Service established in 1946, the first national service to be implemented.

Medical advances

A blood collection program was initiated in the US in 1940 and Edwin Cohn pioneered the process of blood fractionation. He worked out the techniques for isolating theserum albumin

Serum albumin, often referred to simply as blood albumin, is an albumin (a type of globular protein) found in vertebrate blood. Human serum albumin is encoded by the ''ALB'' gene. Other mammalian forms, such as bovine serum albumin, are chem ...

fraction of blood plasma

Blood plasma is a light Amber (color), amber-colored liquid component of blood in which blood cells are absent, but which contains Blood protein, proteins and other constituents of whole blood in Suspension (chemistry), suspension. It makes up ...

, which is essential for maintaining the osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a Solution (chemistry), solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a soluti ...

in the blood vessel

Blood vessels are the tubular structures of a circulatory system that transport blood throughout many Animal, animals’ bodies. Blood vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to most of the Tissue (biology), tissues of a Body (bi ...

s, preventing their collapse.

The use of blood plasma as a substitute for whole blood and for transfusion purposes was proposed as early as 1918, in the correspondence columns of the ''British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a fortnightly peer-reviewed medical journal, published by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, which in turn is wholly-owned by the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world ...

'', by Gordon R. Ward. At the onset of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, liquid plasma was used in Britain. A large project, known as 'Blood for Britain' began in August 1940 to collect blood in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

hospitals for the export of plasma to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

. A dried plasma package was developed, which reduced breakage and made the transportation, packaging, and storage much simpler.

The resulting dried plasma package came in two tin cans containing 400 cc bottles. One bottle contained enough distilled water to reconstitute the dried plasma contained within the other bottle. In about three minutes, the plasma would be ready to use and could stay fresh for around four hours. Charles R. Drew was appointed medical supervisor, and he was able to transform the

The resulting dried plasma package came in two tin cans containing 400 cc bottles. One bottle contained enough distilled water to reconstitute the dried plasma contained within the other bottle. In about three minutes, the plasma would be ready to use and could stay fresh for around four hours. Charles R. Drew was appointed medical supervisor, and he was able to transform the test tube

A test tube, also known as a culture tube or sample tube, is a common piece of laboratory glassware consisting of a finger-like length of glass or clear plastic tubing, open at the top and closed at the bottom.

Test tubes are usually placed in s ...

methods into the first successful mass production technique.

Another important breakthrough came in 1939–40 when Karl Landsteiner

Karl Landsteiner (; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He emigrated with his family to New York in 1923 at the age of 55 for professional opportunities, working for the Rockefeller ...

, Alex Wiener, Philip Levine, and R.E. Stetson discovered the Rh blood group system, which was found to be the cause of the majority of transfusion reactions up to that time. Three years later, the introduction by J.F. Loutit and Patrick L. Mollison of acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD) solution, which reduced the volume of anticoagulant, permitted transfusions of greater volumes of blood and allowed longer-term storage.

Carl Walter and W.P. Murphy Jr. introduced the plastic bag

A plastic bag, poly bag, or pouch is a type of container made of thin, flexible, plastic film, nonwoven fabric, or plastic textile. Plastic bags are used for containing and transporting goods such as foods, produce, Powder (substance), powders, ...

for blood collection in 1950. Replacing breakable glass

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline solid, non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparency and translucency, transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window pane ...

bottles with durable plastic bags allowed for the evolution of a collection system capable of safe and easy preparation of multiple blood components from a single unit of whole blood.

Further extending the shelf life of stored blood up to 42 days was an anticoagulant preservative, CPDA-1, introduced in 1979, which increased the blood supply and facilitated resource-sharing among blood banks.

Collection and processing

In the U.S., certain standards are set for the collection and processing of each blood product. "Whole blood" (WB) is the proper name for one defined product, specifically unseparated venous blood with an approved preservative added. Most blood for transfusion is collected as whole blood. Autologous donations are sometimes transfused without further modification, however whole blood is typically separated (via centrifugation) into its components, with

In the U.S., certain standards are set for the collection and processing of each blood product. "Whole blood" (WB) is the proper name for one defined product, specifically unseparated venous blood with an approved preservative added. Most blood for transfusion is collected as whole blood. Autologous donations are sometimes transfused without further modification, however whole blood is typically separated (via centrifugation) into its components, with red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s (RBC) in solution being the most commonly used product. Units of WB and RBC are both kept refrigerated at , with maximum permitted storage periods ( shelf lives) of 35 and 42 days respectively. RBC units can also be frozen when buffered with glycerol, but this is an expensive and time-consuming process, and is rarely done. Frozen red cells are given an expiration date of up to ten years and are stored at .

The less-dense blood plasma

Blood plasma is a light Amber (color), amber-colored liquid component of blood in which blood cells are absent, but which contains Blood protein, proteins and other constituents of whole blood in Suspension (chemistry), suspension. It makes up ...

is made into a variety of frozen components, and is labeled differently based on when it was frozen and what the intended use of the product is. If the plasma is frozen promptly and is intended for transfusion, it is typically labeled as fresh frozen plasma

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is a blood product made from the liquid portion of whole blood. It is used to treat conditions in which there are low blood clotting factors (INR > 1.5) or low levels of other blood proteins. It may also be used as the r ...

. If it is intended to be made into other products, it is typically labeled as recovered plasma or plasma for fractionation

Fractionation is a separation process in which a certain quantity of a mixture (of gasses, solids, liquids, enzymes, or isotopes, or a suspension) is divided during a phase transition, into a number of smaller quantities (fractions) in which t ...

. Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate, also called cryo for short, or Cryoprecipitate Antihemophilic factor (AHF), is a frozen blood product prepared from blood plasma. To create cryoprecipitate, plasma is slowly thawed to 1–6 °C. A cold-insoluble precipita ...

can be made from other plasma components. These components must be stored at or colder, but are typically stored at . The layer between the red cells and the plasma is referred to as the buffy coat and is sometimes removed to make platelets

Platelets or thrombocytes () are a part of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping to form a blood clot. Platelets have no cell nucleus; they are fragments of cyto ...

for transfusion. Platelets are typically pooled before transfusion and have a shelf life of 5 to 7 days, or 3 days once the facility that collected them has completed their tests. Platelets are stored at room temperature () and must be rocked/agitated. Since they are stored at room temperature in nutritive solutions, they are at relatively high risk for growing bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

.

Some blood banks also collect products by apheresis

Apheresis ( ἀφαίρεσις (''aphairesis'', "a taking away")) is a medical technology in which the blood of a person is passed through an apparatus that separates one particular constituent and returns the remainder to the circulation. ...

. The most common component collected is plasma via plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis (from the Greek language, Greek πλάσμα, ''plasma'', something molded, and ἀφαίρεσις ''aphairesis'', taking away) is the removal, treatment, and return or exchange of blood plasma or components thereof from and to the ...

, but red blood cells and platelets can be collected by similar methods. These products generally have the same shelf life and storage conditions as their conventionally-produced counterparts.

Donors are sometimes paid; in the U.S. and Europe, most blood ''for transfusion'' is collected from volunteers while plasma for other purposes may be from paid donors.

Most collection facilities as well as hospital blood banks also perform testing to determine the blood type

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is based on the presence and absence of antibody, antibodies and Heredity, inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycop ...

of patients and to identify compatible blood products, along with a battery of tests (e.g. disease) and treatments (e.g. leukocyte filtration) to ensure or enhance quality. The increasingly recognized problem of inadequate efficacy of transfusion is also raising the profile of RBC viability and quality. Notably, U.S. hospitals spend more on dealing with the consequences of transfusion-related complications than on the combined costs of buying, testing/treating, and transfusing their blood.

Storage and management

Routine blood storage is 42 days or 6 weeks for stored packed ''red blood cells'' (also called "StRBC" or "pRBC"), by far the most commonly transfused blood product, and involves refrigeration but usually not freezing. There has been increasing controversy about whether a given product unit's age is a factor in transfusion efficacy, specifically on whether "older" blood directly or indirectly increases risks of complications. Studies have not been consistent on answering this question, with some showing that older blood is indeed less effective but with others showing no such difference; nevertheless, as storage time remains the only available way to estimate quality status or loss, a ''first-in-first-out'' inventory management approach is standard presently. It is also important to consider that there is large ''variability'' in storage results for different donors, which combined with limited available quality testing, poses challenges to clinicians and regulators seeking reliable indicators of quality for blood products and storage systems. Transfusions of ''platelets'' are comparatively far less numerous, but they present unique storage/management issues. Platelets may only be stored for 7 days, due largely to their greater potential for contamination, which is in turn due largely to a higher storage temperature.RBC storage lesion

Insufficient transfusion efficacy can result from red blood cell (RBC) blood product units damaged by so-called ''storage lesion''—a set of biochemical and biomechanical changes which occur during storage. With red cells, this can decrease viability and ability for tissue oxygenation. Although some of the biochemical changes are reversible after the blood is transfused, the biomechanical changes are less so, and rejuvenation products are not yet able to adequately reverse this phenomenon. Current regulatory measures are in place to minimize RBC storage lesion—including a maximum shelf life (currently 42 days), a maximum auto-hemolysis threshold (currently 1% in the US), and a minimum level of post-transfusion RBC survival ''in vivo'' (currently 75% after 24 hours). However, all of these criteria are applied in a universal manner that does not account for differences among units of product; for example, testing for the post-transfusion RBC survival ''in vivo'' is done on a sample of healthy volunteers, and then compliance is presumed for all RBC units based on universal (GMP) processing standards. RBC survival does not guarantee efficacy, but it is a necessary prerequisite for cell function, and hence serves as a regulatory proxy. Opinions vary as to the best way to determine transfusion efficacy in a patient ''in vivo''. In general, there are not yet any ''in vitro'' tests to assess quality deterioration or preservation for specific units of RBC blood product prior to their transfusion, though there is exploration of potentially relevant tests based on RBC membrane properties such as erythrocyte deformability and erythrocyte fragility (mechanical). Many physicians have adopted a so-called "restrictive protocol"—whereby transfusion is held to a minimum—due in part to the noted uncertainties surrounding storage lesion, in addition to the very high direct and indirect costs of transfusions, along with the increasing view that many transfusions are inappropriate or use too many RBC units.Platelet storage lesion

Platelet storage lesion is a very different phenomenon from RBC storage lesion, due largely to the different functions of the products and purposes of the respective transfusions, along with different processing issues and inventory management considerations.Alternative inventory and release practices

Although as noted the primary inventory-management approach is first in, first out (FIFO) to minimize product expiration, there are some deviations from this policy—both in current practice as well as under research. For example, exchange transfusion of RBC in neonates calls for use of blood product that is five days old or less, to "ensure" optimal cell function. Also, some hospital blood banks will attempt to accommodate physicians' requests to provide low-aged RBC product for certain kinds of patients (e.g. cardiac surgery). More recently, novel approaches are being explored to complement or replace FIFO. One is to balance the desire to reduce average product age (at transfusion) with the need to maintain sufficient availability of non-outdated product, leading to a strategic blend of FIFO with last in, first out (LIFO).Long-term storage

"Long-term" storage for all blood products is relatively uncommon, compared to routine/short-term storage.Cryopreservation

Cryopreservation or cryoconservation is a process where biological material - cells, tissues, or organs - are frozen to preserve the material for an extended period of time. At low temperatures (typically or using liquid nitrogen) any cell ...

of red blood cells is done to store rare units for up to ten years. The cells are incubated in a glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

solution which acts as a cryoprotectant

A cryoprotectant is a substance used to protect biological tissue from freezing damage (i.e. that due to ice formation). Arctic and Antarctic insects, fish and amphibians create cryoprotectants ( antifreeze compounds and antifreeze proteins) in th ...

("antifreeze") within the cells. The units are then placed in special sterile containers in a freezer at very low temperatures. The exact temperature depends on the glycerol concentration.

See also

* Medical technologist *Phlebotomist

Phlebotomy is the process of making a puncture in a vein, usually in the arm, with a cannula for the purpose of drawing blood. The procedure itself is known as a venipuncture, which is also used for intravenous therapy. A person who performs a ...

* Blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is the process of transferring blood products into a person's Circulatory system, circulation intravenously. Transfusions are used for various medical conditions to replace lost components of the blood. Early transfusions used ...

References

Further reading

* Kara W. Swanson, ''Banking on the Body: The Market in Blood, Milk, and Sperm in Modern America.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.External links

Animated Venipuncture tutorial

{{DEFAULTSORT:Blood Bank Transfusion medicine Blood donation