Biomolecular engineering on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Biomolecular engineering is the application of engineering principles and practices to the purposeful manipulation of molecules of biological origin. Biomolecular engineers integrate knowledge of

The

The

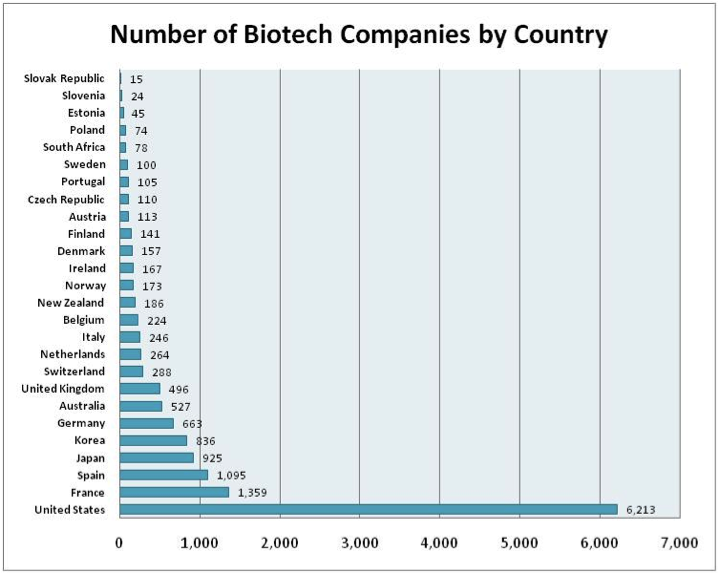

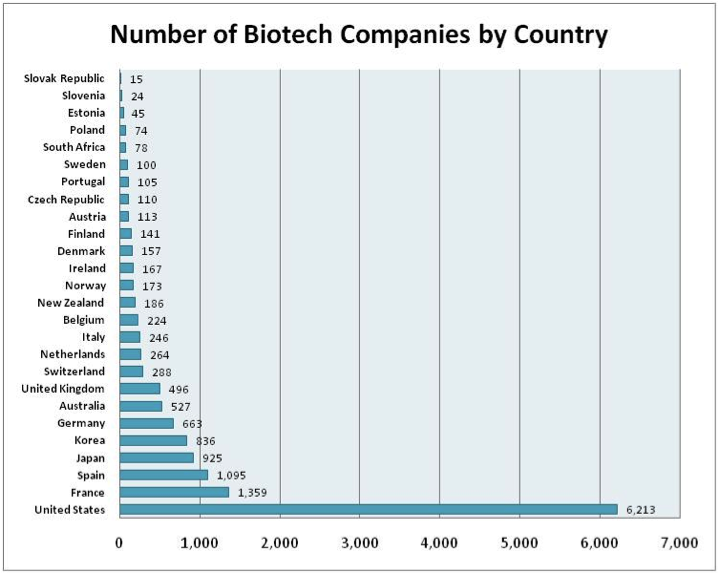

Biomolecular engineering is an extensive discipline with applications in many different industries and fields. As such, it is difficult to pinpoint a general perspective on the Biomolecular engineering profession. The biotechnology industry, however, provides an adequate representation. The biotechnology industry, or biotech industry, encompasses all firms that use biotechnology to produce goods or services or to perform biotechnology research and development. In this way, it encompasses many of the industrial applications of the biomolecular engineering discipline. By examination of the biotech industry, it can be gathered that the principal leader of the industry is the United States, followed by France and Spain. It is also true that the focus of the biotechnology industry and the application of biomolecular engineering is primarily clinical and medical. People are willing to pay for good health, so most of the money directed towards the biotech industry stays in health-related ventures.

Biomolecular engineering is an extensive discipline with applications in many different industries and fields. As such, it is difficult to pinpoint a general perspective on the Biomolecular engineering profession. The biotechnology industry, however, provides an adequate representation. The biotechnology industry, or biotech industry, encompasses all firms that use biotechnology to produce goods or services or to perform biotechnology research and development. In this way, it encompasses many of the industrial applications of the biomolecular engineering discipline. By examination of the biotech industry, it can be gathered that the principal leader of the industry is the United States, followed by France and Spain. It is also true that the focus of the biotechnology industry and the application of biomolecular engineering is primarily clinical and medical. People are willing to pay for good health, so most of the money directed towards the biotech industry stays in health-related ventures.

where di= crystallizer impeller diameter

Ni= impeller rotation rate

Biomolecular engineering at interfaces

(article)

Recent Progress in Biomolecular Engineering

* Biomolecular sensors (alk. paper)

AIChE International Conference on Biomolecular Engineering

{{Engineering fields Biological processes Biotechnology

biological processes

Biological processes are those processes that are necessary for an organism to live and that shape its capacities for interacting with its environment. Biological processes are made of many chemical reactions or other events that are involved in ...

with the core knowledge of chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of the operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials ...

in order to focus on molecular level solutions to issues and problems in the life sciences related to the environment, agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

, industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

, food production

The food industry is a complex, global network of diverse businesses that supplies most of the food consumed by the World population, world's population. The food industry today has become highly diversified, with manufacturing ranging from sm ...

, biotechnology

Biotechnology is a multidisciplinary field that involves the integration of natural sciences and Engineering Science, engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms and parts thereof for products and services. Specialists ...

, biomanufacturing, and medicine.

Biomolecular engineers purposefully manipulate carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s, protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s and lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s within the framework of the relation between their structure (see: nucleic acid structure, carbohydrate chemistry

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ma ...

, protein structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, which are the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid ...

,), function (see: protein function) and properties and in relation to applicability to such areas as environmental remediation

Environmental remediation is the cleanup of hazardous substances dealing with the removal, treatment and containment of pollution or contaminants from Natural environment, environmental media such as soil, groundwater, sediment. Remediation may be ...

, crop and livestock production, biofuel cells and biomolecular diagnostics. The thermodynamics and kinetics of molecular recognition in enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s, antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

, DNA hybridization

In molecular biology, hybridization (or hybridisation) is a phenomenon in which single-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecules anneal to complementary DNA or RNA. Though a double-stranded DNA sequence is generally ...

, bio-conjugation/bio-immobilization and bioseparations are studied. Attention is also given to the rudiments of engineered biomolecules in cell signaling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the Biological process, process by which a Cell (biology), cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all Cell (biol ...

, cell growth kinetics, biochemical pathway engineering and bioreactor engineering.

Timeline

History

During World War II, the need for large quantities ofpenicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

of acceptable quality brought together chemical engineers and microbiologists to focus on penicillin production. This created the right conditions to start a chain of reactions that lead to the creation of the field of biomolecular engineering. Biomolecular engineering was first defined in 1992 by the U.S. National Institutes of Health as research at the interface of chemical engineering and biology with an emphasis at the molecular level". Although first defined as research, biomolecular engineering has since become an academic discipline and a field of engineering practice. Herceptin

Trastuzumab, sold under the brand name Herceptin among others, is a monoclonal antibody used to treat breast cancer and stomach cancer. It is specifically used for cancer that is HER2 receptor positive. It may be used by itself or together w ...

, a humanized Mab for breast cancer treatment, became the first drug designed by a biomolecular engineering approach and was approved by the U.S. FDA. Also, ''Biomolecular Engineering'' was a former name of the journal '' New Biotechnology''.

Future

Bio-inspired technologies of the future can help explain biomolecular engineering. Looking at theMoore's law

Moore's law is the observation that the Transistor count, number of transistors in an integrated circuit (IC) doubles about every two years. Moore's law is an observation and Forecasting, projection of a historical trend. Rather than a law of ...

"Prediction", in the future quantum

In physics, a quantum (: quanta) is the minimum amount of any physical entity (physical property) involved in an interaction. The fundamental notion that a property can be "quantized" is referred to as "the hypothesis of quantization". This me ...

and biology-based processors are "big" technologies. With the use of biomolecular engineering, the way our processors work can be manipulated in order to function in the same sense a biological cell work. Biomolecular engineering has the potential to become one of the most important scientific disciplines because of its advancements in the analyses of gene expression patterns as well as the purposeful manipulation of many important biomolecules to improve functionality. Research in this field may lead to new drug discoveries, improved therapies, and advancement in new bioprocess technology. With the increasing knowledge of biomolecules, the rate of finding new high-value molecules including but not limited to antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

, enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s, vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

s, and therapeutic peptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty am ...

s will continue to accelerate. Biomolecular engineering will produce new designs for therapeutic drugs and high-value biomolecules for treatment or prevention of cancers, genetic diseases, and other types of metabolic diseases. Also, there is anticipation of industrial enzymes that are engineered to have desirable properties for process improvement as well the manufacturing of high-value biomolecular products at a much lower production cost. Using recombinant technology, new antibiotics that are active against resistant strains will also be produced.

Basic biomolecules

Biomolecular engineering deals with the manipulation of many key biomolecules. These include, but are not limited to, proteins, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, and lipids. These molecules are the basic building blocks of life and by controlling, creating, and manipulating their form and function there are many new avenues and advantages available to society. Since everybiomolecule

A biomolecule or biological molecule is loosely defined as a molecule produced by a living organism and essential to one or more typically biological processes. Biomolecules include large macromolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids ...

is different, there are a number of techniques used to manipulate each one respectively.

Proteins

Proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, re ...

are polymers that are made up of amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

chains linked with peptide bonds

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein chai ...

. They have four distinct levels of structure: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary.

Primary structure refers to the amino acid backbone sequence. Secondary structure focuses on minor conformations that develop as a result of the hydrogen bonding between the amino acid chain. If most of the protein contains intermolecular hydrogen bonds it is said to be fibrillar, and the majority of its secondary structure will be beta sheets. However, if the majority of the orientation contains intramolecular hydrogen bonds, then the protein is referred to as globular and mostly consists of alpha helices

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the secondary structure of proteins. It is also the most extreme type of l ...

. There are also conformations that consist of a mix of alpha helices and beta sheets as well as a beta helixes with an alpha sheet

Alpha sheet (also known as alpha pleated sheet or polar pleated sheet) is an atypical secondary structure in proteins, first proposed by Linus Pauling and Robert Corey in 1951.Pauling, L. & Corey, R. B. (1951). The pleated sheet, a new layer con ...

s.

The tertiary structure of proteins deal with their folding process and how the overall molecule is arranged. Finally, a quaternary structure is a group of tertiary proteins coming together and binding.

With all of these levels, proteins have a wide variety of places in which they can be manipulated and adjusted. Techniques are used to affect the amino acid sequence of the protein (site-directed mutagenesis), the folding and conformation of the protein, or the folding of a single tertiary protein within a quaternary protein matrix.

Proteins that are the main focus of manipulation are typically enzymes

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as pro ...

. These are proteins that act as catalysts

Catalysis () is the increase in reaction rate, rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst ...

for biochemical reaction

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

s. By manipulating these catalysts, the reaction rates, products, and effects can be controlled. Enzymes and proteins are important to the biological field and research that there are specific divisions of engineering focusing only on proteins and enzymes.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ma ...

are another important biomolecule. These are polymers, called polysaccharides

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

, which are made up of chains of simple sugars connected via glycosidic bonds

A glycosidic bond or glycosidic linkage is a type of ether bond that joins a carbohydrate (sugar) molecule to another group, which may or may not be another carbohydrate.

A glycosidic bond is formed between the hemiacetal or hemiketal group of ...

. These monosaccharides

Monosaccharides (from Greek ''monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhydr ...

consist of a five to six carbon ring that contains carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen - typically in a 1:2:1 ratio, respectively. Common monosaccharides are glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

, fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and gal ...

, and ribose. When linked together monosaccharides can form disaccharides

A disaccharide (also called a double sugar or ''biose'') is the sugar formed when two monosaccharides are joined by glycosidic linkage. Like monosaccharides, disaccharides are simple sugars soluble in water. Three common examples are sucrose, l ...

, oligosaccharides

An oligosaccharide (; ) is a saccharide polymer containing a small number (typically three to ten) of monosaccharides (simple sugars). Oligosaccharides can have many functions including cell recognition and cell adhesion.

They are normally presen ...

, and polysaccharides: the nomenclature is dependent on the number of monosaccharides linked together. Common dissacharides, two monosaccharides joined, are sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

, maltose

}

Maltose ( or ), also known as maltobiose or malt sugar, is a disaccharide formed from two units of glucose joined with an α(1→4) bond. In the isomer isomaltose, the two glucose molecules are joined with an α(1→6) bond. Maltose is the tw ...

, and lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

. Important polysaccharides, links of many monosaccharides, are cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

, starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diet ...

, and chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

.

Cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

is a polysaccharide made up of beta 1-4 linkages between repeat glucose monomers. It is the most abundant source of sugar in nature and is a major part of the paper industry.

Starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diet ...

is also a polysaccharide made up of glucose monomers; however, they are connected via an alpha 1-4 linkage instead of beta. Starches, particularly amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large ...

, are important in many industries, including the paper, cosmetic, and food.

Chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

is a derivation of cellulose, possessing an acetamide

Acetamide (systematic name: ethanamide) is an organic compound with the formula CH3CONH2. It is an amide derived from ammonia and acetic acid. It finds some use as a plasticizer and as an industrial solvent. The related compound ''N'',''N''-dime ...

group instead of an –OH on one of its carbons. Acetimide group is deacetylated the polymer chain is then called chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed of randomly distributed β-(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine (deacetylated unit) and ''N''-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated unit). It is made by treating the chitin shells of shrimp and other crusta ...

. Both of these cellulose derivatives are a major source of research for the biomedical and food industries. They have been shown to assist with blood clotting

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a thrombus, blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of co ...

, have antimicrobial properties, and dietary applications. A lot of engineering and research is focusing on the degree of deacetylation

:

In chemistry, acetylation is an organic esterification reaction with acetic acid. It introduces an acetyl group into a chemical compound. Such compounds are termed ''acetate esters'' or simply ''acetates''. Deacetylation is the opposite react ...

that provides the most effective result for specific applications.

Nucleic acids

Nucleic acids

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic a ...

are macromolecules that consist of DNA and RNA which are biopolymers consisting of chains of biomolecules. These two molecules are the genetic code and template that make life possible. Manipulation of these molecules and structures causes major changes in function and expression of other macromolecules. Nucleosides

Nucleosides are glycosylamines that can be thought of as nucleotides without a phosphate group. A nucleoside consists simply of a nucleobase (also termed a nitrogenous base) and a five-carbon sugar (ribose or 2'-deoxyribose) whereas a nucleotide ...

are glycosylamines containing a nucleobase bound to either ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this comp ...

or deoxyribose sugar via a beta-glycosidic linkage. The sequence of the bases determine the genetic code. Nucleotides

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

are nucleosides that are phosphorylated by specific kinases

In biochemistry, a kinase () is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes the transfer of phosphate groups from High-energy phosphate, high-energy, phosphate-donating molecules to specific Substrate (biochemistry), substrates. This process is known as ...

via a phosphodiester bond

In chemistry, a phosphodiester bond occurs when exactly two of the hydroxyl groups () in phosphoric acid react with hydroxyl groups on other molecules to form two ester bonds. The "bond" involves this linkage . Discussion of phosphodiesters is d ...

. Nucleotides are the repeating structural units of nucleic acids. The nucleotides are made of a nitrogenous base, a pentose (ribose for RNA or deoxyribose for DNA), and three phosphate groups. See, Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis is a molecular biology method that is used to make specific and intentional mutating changes to the DNA sequence of a gene and any gene products. Also called site-specific mutagenesis or oligonucleotide-directed mutagenes ...

, recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

, and ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

s.

Lipids

Lipids

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins Vitamin A, A, Vitamin D, D, Vitamin E, E and Vitamin K, K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The fu ...

are biomolecules that are made up of glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

derivatives bonded with fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

chains. Glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

is a simple polyol

In organic chemistry, a polyol is an organic compound containing multiple hydroxyl groups (). The term "polyol" can have slightly different meanings depending on whether it is used in food science or polymer chemistry. Polyols containing two, th ...

that has a formula of C3H5(OH)3. Fatty acids are long carbon chains that have a carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an Substituent, R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is often written as or , sometimes as with R referring to an organyl ...

group at the end. The carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

chains can be either saturated with hydrogen; every carbon bond is occupied by a hydrogen atom or a single bond to another carbon in the carbon chain, or they can be unsaturated; namely, there are double bonds between the carbon atoms in the chain. Common fatty acids include lauric acid

Lauric acid, systematically dodecanoic acid, is a saturated fatty acid with a 12-carbon atom chain, thus having many properties of Medium-chain triglyceride, medium-chain fatty acids. It is a bright white, powdery solid with a faint odor of Piment ...

, stearic acid

Stearic acid ( , ) is a saturated fatty acid with an 18-carbon chain. The IUPAC name is octadecanoic acid. It is a soft waxy solid with the formula . The triglyceride derived from three molecules of stearic acid is called stearin. Stearic acid ...

, and oleic acid

Oleic acid is a fatty acid that occurs naturally in various animal and vegetable fats and oils. It is an odorless, colorless oil, although commercial samples may be yellowish due to the presence of impurities. In chemical terms, oleic acid is cl ...

. The study and engineering of lipids typically focuses on the manipulation of lipid membranes and encapsulation. Cellular membranes and other biological membranes typically consist of a phospholipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a l ...

membrane, or a derivative thereof. Along with the study of cellular membranes, lipids are also important molecules for energy storage. By utilizing encapsulation properties and thermodynamic

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws of th ...

characteristics, lipids become significant assets in structure and energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

control when engineering molecules.

Of molecules

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

are DNA biomolecules that contain genetic sequences that are not native to the organism's genome. Using recombinant techniques, it is possible to insert, delete, or alter a DNA sequence precisely without depending on the location of restriction sites. Recombinant DNA is used for a wide range of applications.

Method

The traditional method for creating recombinant DNA typically involves the use ofplasmids

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

in the host bacteria. The plasmid contains a genetic sequence corresponding to the recognition site of a restriction endonuclease, such as EcoR1

EcoRI (pronounced "eco R one") is a restriction endonuclease enzyme isolated from species ''E. coli.'' It is a restriction enzyme that cleaves DNA double helices into fragments at specific sites, and is also a part of the restriction modification ...

. After foreign DNA fragments, which have also been cut with the same restriction endonuclease, have been inserted into host cell, the restriction endonuclease gene is expressed by applying heat, or by introducing a biomolecule, such as arabinose. Upon expression, the enzyme will cleave the plasmid at its corresponding recognition site creating sticky ends

DNA ends refer to the properties of the ends of linear DNA molecules, which in molecular biology are described as "sticky" or "blunt" based on the shape of the complementary strands at the terminus. In sticky ends, one strand is longer than the o ...

on the plasmid. Ligases then joins the sticky ends to the corresponding sticky ends of the foreign DNA fragments creating a recombinant DNA plasmid.

Advances in genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of Genetic engineering techniques, technologies used to change the genet ...

have made the modification of genes in microbes quite efficient allowing constructs to be made in about a weeks worth of time. It has also made it possible to modify the organism's genome itself. Specifically, use of the genes from the bacteriophage lambda

Lambda phage (coliphage λ, scientific name ''Lambdavirus lambda'') is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species ''Escherichia coli'' (''E. coli''). It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950. The wild type of ...

are used in recombination. This mechanism, known as recombineering, utilizes the three proteins Exo, Beta, and Gam, which are created by the genes exo, bet, and gam respectively. Exo is a double stranded DNA exonuclease

Exonucleases are enzymes that work by cleaving nucleotides one at a time from the end (exo) of a polynucleotide chain. A hydrolyzing reaction that breaks phosphodiester bonds at either the 3′ or the 5′ end occurs. Its close relative is th ...

with 5' to 3' activity. It cuts the double stranded DNA leaving 3' overhangs. Beta is a protein that binds to single stranded DNA and assists homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

by promoting annealing between the homology regions of the inserted DNA and the chromosomal DNA. Gam functions to protect the DNA insert from being destroyed by native nucleases within the cell.

Applications

Recombinant DNA can be engineered for a wide variety of purposes. The techniques utilized allow for specific modification of genes making it possible to modify any biomolecule. It can be engineered for laboratory purposes, where it can be used to analyze genes in a given organism. In the pharmaceutical industry, proteins can be modified using recombination techniques. Some of these proteins include humaninsulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

. Recombinant insulin is synthesized by inserting the human insulin gene into ''E. coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly foun ...

'', which then produces insulin for human use. Other proteins, such as human growth hormone

Growth hormone (GH) or somatotropin, also known as human growth hormone (hGH or HGH) in its human form, is a peptide hormone that stimulates growth, cell reproduction, and cell regeneration in humans and other animals. It is thus important in ...

, factor VIII

Coagulation factor VIII (Factor VIII, FVIII, also known as anti-hemophilic factor (AHF)) is an essential blood clotting protein. In humans, it is encoded by ''F8'' gene. Defects in this gene result in hemophilia A, an X-linked bleeding disorder ...

, and hepatitis B vaccine are produced using similar means. Recombinant DNA can also be used for diagnostic methods involving the use of the ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

method. This makes it possible to engineer antigens, as well as the enzymes attached, to recognize different substrates or be modified for bioimmobilization. Recombinant DNA is also responsible for many products found in the agricultural industry. Genetically modified food

Genetically modified foods (GM foods), also known as genetically engineered foods (GE foods), or bioengineered foods are foods produced from organisms that have had changes introduced into their DNA using various methods of genetic engineering. G ...

, such as golden rice

Golden rice is a variety of rice ('' Oryza sativa'') produced through genetic engineering to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, in the edible parts of the rice. It is intended to produce a fortified food to be grown and ...

, has been engineered to have increased production of vitamin A

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin that is an essential nutrient. The term "vitamin A" encompasses a group of chemically related organic compounds that includes retinol, retinyl esters, and several provitamin (precursor) carotenoids, most not ...

for use in societies and cultures where dietary vitamin A is scarce. Other properties that have been engineered into crops include herbicide-resistance and insect-resistance.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis is a molecular biology method that is used to make specific and intentional mutating changes to the DNA sequence of a gene and any gene products. Also called site-specific mutagenesis or oligonucleotide-directed mutagenes ...

is a technique that has been around since the 1970s. The early days of research in this field yielded discoveries about the potential of certain chemicals such as bisulfite and aminopurine to change certain bases in a gene. This research continued, and other processes were developed to create certain nucleotide sequences on a gene, such as the use of restriction enzymes to fragment certain viral strands and use them as primers for bacterial plasmids. The modern method, developed by Michael Smith in 1978, uses an oligonucleotide that is complementary to a bacterial plasmid with a single base pair mismatch or a series of mismatches.

General procedure

Site directed mutagenesis is a valuable technique that allows for the replacement of a single base in an oligonucleotide or gene. The basics of this technique involve the preparation of a primer that will be a complementary strand to a wild type bacterial plasmid. This primer will have a base pair mismatch at the site where the replacement is desired. The primer must also be long enough such that the primer will anneal to the wild type plasmid. After the primer anneals, a DNA polymerase will complete the primer. When the bacterial plasmid is replicated, the mutated strand will be replicated as well. The same technique can be used to create a gene insertion or deletion. Often, an antibiotic resistant gene is inserted along with the modification of interest and the bacteria are cultured on an antibiotic medium. The bacteria that were not successfully mutated will not survive on this medium, and the mutated bacteria can easily be cultured.

Applications

Site-directed mutagenesis can be helpful for many different reasons. A single base-pair replacement will change thecodon

Genetic code is a set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material (DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links prote ...

, potentially replacing an amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

in a protein. Mutagenesis can help determine the function of proteins and the roles of specific amino acids. If an amino acid near the active site is mutated, the kinetic parameters may change drastically, or the enzyme might behave differently. Another application of site-directed mutagenesis is exchanging an amino acid residue far from the active site with a lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. Lysine contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form when the lysine is dissolved in water at physiological pH), an α-carboxylic acid group ( ...

residue or cysteine

Cysteine (; symbol Cys or C) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine enables the formation of Disulfide, disulfide bonds, and often participates in enzymatic reactions as ...

residue. These amino acids make it easier to covalently bond the enzyme to a solid surface, which allows for enzyme re-use and the use of enzymes in continuous processes. Sometimes, amino acids with non-natural functional groups (such as an aldehyde introduced through an aldehyde tag) are added to proteins.Peng Wua, Wenqing Shuia, Brian L. Carlsona, Nancy Hua, David Rabukaa, Julia Leea, and Carolyn R. Bertozzi (2009). "Site-specific chemical modification of recombinant proteins produced in mammalian cells by using the genetically encoded aldehyde tag". ''Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A.'' 106 (9):3000-5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0807820106 These additions may be for ease of bioconjugation or to study the effects of amino acid changes on the form and function of the proteins.

One example of how mutagenesis is used is found in the coupling of site-directed mutagenesis and PCR to reduce interleukin-6

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) is an interleukin that acts as both a pro-inflammatory cytokine and an anti-inflammatory myokine. In humans, it is encoded by the ''IL6'' gene.

In addition, osteoblasts secrete IL-6 to stimulate osteoclast formation. Smoo ...

activity in cancerous cells. In another example, ''Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'' (), known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacill ...

'' is used in site-directed mutagenesis, to secrete the enzyme subtilisin

Subtilisin is a protease (a protein-digesting enzyme) initially obtained from ''Bacillus subtilis''.

Subtilisins belong to subtilases, a group of serine proteases that – like all serine proteases – initiate the nucleophilic attack on the ...

through the cell wall. Biomolecular engineers can purposely manipulate this gene to essentially make the cell a factory for producing whatever protein the insertion in the gene codes.

Bio-immobilization and bio-conjugation

Bio-immobilization and bio-conjugation is the purposeful manipulation of a biomolecule's mobility by chemical or physical means to obtain a desired property. Immobilization of biomolecules allows exploiting characteristics of the molecule under controlled environments. For example , the immobilization of glucose oxidase on calcium alginate gel beads can be used in a bioreactor. The resulting product will not need purification to remove the enzyme because it will remain linked to the beads in the column. Examples of types of biomolecules that are immobilized are enzymes, organelles, and complete cells. Biomolecules can be immobilized using a range of techniques. The most popular are physical entrapment, adsorption, and covalent modification. *Physical entrapment - the use of a polymer to contain the biomolecule in a matrix without chemical modification. Entrapment can be between lattices of polymer, known as gel entrapment, or within micro-cavities of synthetic fibers, known as fiber entrapment. Examples include entrapment of enzymes such as glucose oxidase in gel column for use as abioreactor

A bioreactor is any manufactured device or system that supports a biologically active environment. In one case, a bioreactor is a vessel in which a chemical reaction, chemical process is carried out which involves organisms or biochemistry, biochem ...

. Important characteristic with entrapment is biocatalyst remains structurally unchanged, but creates large diffusion barriers for substrates.

* Adsorption

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the ''adsorbate'' on the surface of the ''adsorbent''. This process differs from absorption, in which a ...

- immobilization of biomolecules due to interaction between the biomolecule and groups on support. Can be physical adsorption, ionic bonding, or metal binding chelation. Such techniques can be performed under mild conditions and relatively simple, although the linkages are highly dependent upon pH, solvent and temperature. Examples include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

* Covalent modification- involves chemical reactions between certain functional groups and matrix. This method forms stable complex between biomolecule and matrix and is suited for mass production. Due to the formation of chemical bond to functional groups, loss of activity can occur. Examples of chemistries used are DCC coupling PDC coupling and EDC/NHS coupling, all of which take advantage of the reactive amines on the biomolecule's surface.

Because immobilization restricts the biomolecule, care must be given to ensure that functionality is not entirely lost. Variables to consider are pH, temperature, solvent choice, ionic strength, orientation of active sites due to conjugation. For enzymes, the conjugation will lower the kinetic rate due to a change in the 3-dimensional structure, so care must be taken to ensure functionality is not lost.

Bio-immobilization is used in technologies such as diagnostic bioassay

A bioassay is an analytical method to determine the potency or effect of a substance by its effect on animal testing, living animals or plants (''in vivo''), or on living cells or tissues (''in vitro''). A bioassay can be either quantal or quantit ...

s, biosensor

A biosensor is an analytical device, used for the detection of a chemical substance, that combines a biological component with a physicochemical detector.

The ''sensitive biological element'', e.g. tissue, microorganisms, organelles, cell rece ...

s, ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

, and bioseparations. Interleukin (IL-6) can also be bioimmobilized on biosensors. The ability to observe these changes in IL-6 levels is important in diagnosing an illness. A cancer patient will have elevated IL-6 level and monitoring those levels will allow the physician to watch the disease progress. A direct immobilization of IL-6 on the surface of a biosensor offers a fast alternative to ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

.

Polymerase chain reaction

polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) is a scientific technique that is used to replicate a piece of a DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

molecule by several orders of magnitude. PCR implements a cycle of repeated heated and cooling known as thermal cycling along with the addition of DNA primers and DNA polymerases

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create t ...

to selectively replicate the DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

fragment of interest. The technique was developed by Kary Mullis

Kary Banks Mullis (December 28, 1944August 7, 2019) was an American biochemist. In recognition of his role in the invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and was ...

in 1983 while working for the Cetus Corporation. Mullis would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

in 1993 as a result of the impact that PCR had in many areas such as DNA cloning

Molecular cloning is a set of experimental methods in molecular biology that are used to assemble recombinant DNA molecules and to direct their replication within host organisms. The use of the word ''cloning'' refers to the fact that the metho ...

, DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The ...

, and gene analysis.

Biomolecular engineering techniques involved in PCR

A number of biomolecular engineering strategies have played a very important role in the development and practice of PCR. For instance a crucial step in ensuring the accurate replication of the desired DNA fragment is the creation of the correct DNA primer. The most common method of primer synthesis is by the phosphoramidite method. This method includes the biomolecular engineering of a number of molecules to attain the desired primer sequence. The most prominent biomolecular engineering technique seen in this primer design method is the initial bioimmobilization of a nucleotide to a solid support. This step is commonly done via the formation of a covalent bond between the 3'-hydroxy group of the first nucleotide of the primer and the solid support material. Furthermore, as the DNA primer is created certain functional groups of nucleotides to be added to the growing primer require blocking to prevent undesired side reactions. This blocking of functional groups as well as the subsequent de-blocking of the groups, coupling of subsequent nucleotides, and eventual cleaving from the solid support are all methods of manipulation of biomolecules that can be attributed to biomolecular engineering. The increase in interleukin levels is directly proportional to the increased death rate in breast cancer patients. PCR paired with Western blotting and ELISA help define the relationship between cancer cells and IL-6.Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence o ...

is an assay that utilizes the principle of antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

-antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

recognition to test for the presence of certain substances. The three main types of ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

tests which are indirect ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

, sandwich ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

, and competitive ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

all rely on the fact that antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

have an affinity for only one specific antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

. Furthermore, these antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

s or antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

can be attached to enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s which can react to create a colorimetric result indicating the presence of the antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

or antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

of interest. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assays are used most commonly as diagnostic tests to detect HIV antibodies in blood samples to test for HIV, human chorionic gonadotropin

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is a hormone for the maternal recognition of pregnancy produced by trophoblast cells that are surrounding a growing embryo (syncytiotrophoblast initially), which eventually forms the placenta after implantat ...

molecules in urine to indicate pregnancy, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis.

First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' ha ...

antibodies in blood to test patients for tuberculosis. Furthermore, ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

is also widely used as a toxicology screen to test people's serum for the presence of illegal drugs.

Techniques involved in ELISA

Although there are three different types of solid stateenzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence o ...

, all three types begin with the bioimmobilization of either an antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

or antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

to a surface. This bioimmobilization is the first instance of biomolecular engineering that can be seen in ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

implementation. This step can be performed in a number of ways including a covalent linkage to a surface which may be coated with protein or another substance. The bioimmobilization can also be performed via hydrophobic interactions

The hydrophobic effect is the observed tendency of nonpolar substances to aggregate in an aqueous solution and to be excluded by water. The word hydrophobic literally means "water-fearing", and it describes the segregation of water and nonpolar ...

between the molecule and the surface. Because there are many different types of ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

s used for many different purposes the biomolecular engineering that this step requires varies depending on the specific purpose of the ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

.

Another biomolecular engineering technique that is used in ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

development is the bioconjugation

Bioconjugation is a chemical strategy to form a stable Covalent bond, covalent link between two molecules, at least one of which is a biomolecule. Methods to conjugate biomolecules are applied in various field, including medicine, diagnostics, ...

of an enzyme to either an antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

or antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

depending on the type of ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

. There is much to consider in this enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

bioconjugation

Bioconjugation is a chemical strategy to form a stable Covalent bond, covalent link between two molecules, at least one of which is a biomolecule. Methods to conjugate biomolecules are applied in various field, including medicine, diagnostics, ...

such as avoiding interference with the active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate, the ''binding s ...

of the enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

as well as the antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

binding site in the case that the antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

is conjugated with enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

. This bioconjugation

Bioconjugation is a chemical strategy to form a stable Covalent bond, covalent link between two molecules, at least one of which is a biomolecule. Methods to conjugate biomolecules are applied in various field, including medicine, diagnostics, ...

is commonly performed by creating crosslinks between the two molecules of interest and can require a wide variety of different reagents depending on the nature of the specific molecules.

Interleukin (IL-6) is a signaling protein that has been known to be present during an immune response. The use of the sandwich type ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay is a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence of ...

quantifies the presence of this cytokine within spinal fluid or bone marrow samples.

Applications and fields

In industry

Biomolecular engineering is an extensive discipline with applications in many different industries and fields. As such, it is difficult to pinpoint a general perspective on the Biomolecular engineering profession. The biotechnology industry, however, provides an adequate representation. The biotechnology industry, or biotech industry, encompasses all firms that use biotechnology to produce goods or services or to perform biotechnology research and development. In this way, it encompasses many of the industrial applications of the biomolecular engineering discipline. By examination of the biotech industry, it can be gathered that the principal leader of the industry is the United States, followed by France and Spain. It is also true that the focus of the biotechnology industry and the application of biomolecular engineering is primarily clinical and medical. People are willing to pay for good health, so most of the money directed towards the biotech industry stays in health-related ventures.

Biomolecular engineering is an extensive discipline with applications in many different industries and fields. As such, it is difficult to pinpoint a general perspective on the Biomolecular engineering profession. The biotechnology industry, however, provides an adequate representation. The biotechnology industry, or biotech industry, encompasses all firms that use biotechnology to produce goods or services or to perform biotechnology research and development. In this way, it encompasses many of the industrial applications of the biomolecular engineering discipline. By examination of the biotech industry, it can be gathered that the principal leader of the industry is the United States, followed by France and Spain. It is also true that the focus of the biotechnology industry and the application of biomolecular engineering is primarily clinical and medical. People are willing to pay for good health, so most of the money directed towards the biotech industry stays in health-related ventures.

Scale-up

Scaling up a process involves using data from an experimental-scale operation (model or pilot plant) for the design of a large (scaled-up) unit, of commercial size. Scaling up is a crucial part of commercializing a process. For example,insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

produced by genetically modified Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

bacteria was initialized on a lab-scale, but to be made commercially viable had to be scaled up to an industrial level. In order to achieve this scale-up a lot of lab data had to be used to design commercial sized units. For example, one of the steps in insulin production involves the crystallization of high purity glargin insulin. In order to achieve this process on a large scale we want to keep the Power/Volume ratio of both the lab-scale and large-scale crystallizers the same in order to achieve homogeneous mixing.

We also assume the lab-scale crystallizer

Crystallization is a process that leads to solids with highly organized atoms or molecules, i.e. a crystal. The ordered nature of a crystalline solid can be contrasted with amorphous solids in which atoms or molecules lack regular organization ...

has geometric similarity to the large-scale crystallizer. Therefore,

P/V α Ni3di3

where di= crystallizer impeller diameter

Ni= impeller rotation rate

Related industries

Bioengineering

A broad term encompassing all engineering applied to the life sciences. This field of study utilizes the principles ofbiology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

along with engineering principles to create marketable products. Some bioengineering

Biological engineering or

bioengineering is the application of principles of biology and the tools of engineering to create usable, tangible, economically viable products. Biological engineering employs knowledge and expertise from a number ...

applications include:

*Biomimetics

Biomimetics or biomimicry is the emulation of the models, systems, and elements of nature for the purpose of solving complex human problems. The terms "biomimetics" and "biomimicry" are derived from (''bios''), life, and μίμησις (''mimes ...

- The study and development of synthetic systems that mimic the form and function of natural biologically produced substances and processes.

*Bioprocess engineering

A bioprocess is a specific process that uses complete living cells or their components (e.g., bacteria, enzymes, chloroplasts) to obtain desired products.

Transport of energy and mass is fundamental to many biological and environmental processes ...

- The study and development of process equipment and optimization that aids in the production of many products such as food and pharmaceuticals

Medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal product, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the ...

.

*Industrial microbiology

Industrial microbiology is a branch of biotechnology that applies microbial sciences to create industrial products in mass quantities, often using Microbial cell factory, microbial cell factories. There are multiple ways to manipulate a microorgani ...

- The implementation of microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s in the production of industrial products such as food and antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

s. Another common application of industrial microbiology

Industrial microbiology is a branch of biotechnology that applies microbial sciences to create industrial products in mass quantities, often using Microbial cell factory, microbial cell factories. There are multiple ways to manipulate a microorgani ...

is the treatment of wastewater in chemical plants via utilization of certain microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s.

Biochemistry

Biochemistry is the study of chemical processes in living organisms, including, but not limited to, living matter. Biochemical processes govern all living organisms and living processes and the field of biochemistry seeks to understand and manipulate these processes.Biochemical engineering

*Biocatalysis

Biocatalysis refers to the use of living (biological) systems or their parts to speed up ( catalyze) chemical reactions. In biocatalytic processes, natural catalysts, such as enzymes, perform chemical transformations on organic compounds. Both en ...

– Chemical transformations using enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s.

* Bioseparations – Separation of biologically active molecules.

*Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, Work (thermodynamics), work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed b ...

and Kinetics (chemistry) – Analysis of reactions involving cell growth and biochemicals.

*Bioreactor

A bioreactor is any manufactured device or system that supports a biologically active environment. In one case, a bioreactor is a vessel in which a chemical reaction, chemical process is carried out which involves organisms or biochemistry, biochem ...

design and analysis – Design of reactors for performing biochemical transformations.

Biotechnology

*Biomaterials

A biomaterial is a substance that has been engineered to interact with biological systems for a medical purpose – either a therapeutic (treat, augment, repair, or replace a tissue function of the body) or a diagnostic one. The corresponding f ...

– Design, synthesis and production of new materials to support cells and tissues.

*Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of Genetic engineering techniques, technologies used to change the genet ...

– Purposeful manipulation of the genomes of organisms to produce new phenotypic traits.

*Bioelectronics

Bioelectronics is a field of research in the convergence of biology and electronics.

Definitions

At the first C.E.C. Workshop, in Brussels in November 1991, bioelectronics was defined as 'the use of biological materials and biological archi ...

, Biosensor

A biosensor is an analytical device, used for the detection of a chemical substance, that combines a biological component with a physicochemical detector.

The ''sensitive biological element'', e.g. tissue, microorganisms, organelles, cell rece ...

and Biochip

In molecular biology, biochips are engineered substrates ("miniaturized laboratories") that can host large numbers of simultaneous biochemical reactions. One of the goals of biochip technology is to efficiently screen large numbers of biological ...

– Engineered devices and systems to measure, monitor and control biological processes.

*Bioprocess engineering

A bioprocess is a specific process that uses complete living cells or their components (e.g., bacteria, enzymes, chloroplasts) to obtain desired products.

Transport of energy and mass is fundamental to many biological and environmental processes ...

– Design and maintenance of cell-based and enzyme-based processes for the production of fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Bioelectrical engineering

Bioelectrical engineering involves the electrical fields generated by living cells or organisms. Examples include theelectric potential

Electric potential (also called the ''electric field potential'', potential drop, the electrostatic potential) is defined as electric potential energy per unit of electric charge. More precisely, electric potential is the amount of work (physic ...

developed between muscles or nerves of the body. This discipline requires knowledge in the fields of electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

and biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

to understand and utilize these concepts to improve or better current bioprocesses or technology.

* Bioelectrochemistry - Chemistry concerned with electron/proton transport throughout the cell

*Bioelectronics

Bioelectronics is a field of research in the convergence of biology and electronics.

Definitions

At the first C.E.C. Workshop, in Brussels in November 1991, bioelectronics was defined as 'the use of biological materials and biological archi ...

- Field of research coupling biology and electronics