In

biochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

, biomolecular condensates are a class of

membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

-less

organelles and organelle subdomains, which carry out specialized functions within the

cell.

Unlike many organelles, biomolecular condensate composition is not controlled by a bounding membrane. Instead, condensates can form and maintain organization through a range of different processes, the most well-known of which is

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

of

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s,

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

, and other

biopolymers

Biopolymers are natural polymers produced by the cells of living organisms. Like other polymers, biopolymers consist of monomeric units that are covalently bonded in chains to form larger molecules. There are three main classes of biopolymers, ...

into either

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al emulsions,

gels,

liquid crystal

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as i ...

s, solid

crystals

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macrosc ...

, or

aggregates within cells.

History

Micellar theory

The micellar theory of

Carl Nägeli

Carl Wilhelm von Nägeli (26 or 27 March 1817 – 10 May 1891) was a Swiss botanist. He studied cell division and pollination but became known as the man who discouraged Gregor Mendel from further work on genetics. He rejected natural selecti ...

was developed from his detailed study of

starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diet ...

granules in 1858. Amorphous substances such as starch and cellulose were proposed to consist of building blocks, packed in a loosely crystalline array to form what he later termed "micelles". Water could penetrate between the micelles, and new micelles could form in the interstices between old micelles. The swelling of starch grains and their growth was described by a molecular-aggregate model, which he also applied to the cellulose of the plant cell wall. The modern usage of '

micelle

A micelle () or micella () ( or micellae, respectively) is an aggregate (or supramolecular assembly) of surfactant amphipathic lipid molecules dispersed in a liquid, forming a colloidal suspension (also known as associated colloidal system). ...

' refers strictly to lipids, but its original usage clearly extended to other types of

biomolecule

A biomolecule or biological molecule is loosely defined as a molecule produced by a living organism and essential to one or more typically biological processes. Biomolecules include large macromolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids ...

, and this legacy is reflected to this day in the description of milk as being composed of '

casein

Casein ( , from Latin ''caseus'' "cheese") is a family of related phosphoproteins (CSN1S1, αS1, aS2, CSN2, β, K-casein, κ) that are commonly found in mammalian milk, comprising about 80% of the proteins in cow's milk and between 20% and 60% of ...

micelles'.

Colloidal phase separation theory

The concept of intracellular

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s as an organizing principle for the compartmentalization of living cells dates back to the end of the 19th century, beginning with

William Bate Hardy and

Edmund Beecher Wilson

Edmund Beecher Wilson (October 19, 1856 – March 3, 1939) was a pioneering American zoologist and geneticist. He wrote one of the most influential textbooks in modern biology, ''The Cell''. He discovered the chromosomal XY sex-determination s ...

who described the

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

(then called '

protoplasm

Protoplasm (; ) is the part of a cell that is surrounded by a plasma membrane. It is a mixture of small molecules such as ions, monosaccharides, amino acids, and macromolecules such as proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, etc.

In some definitions ...

') as a

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

. Around the same time,

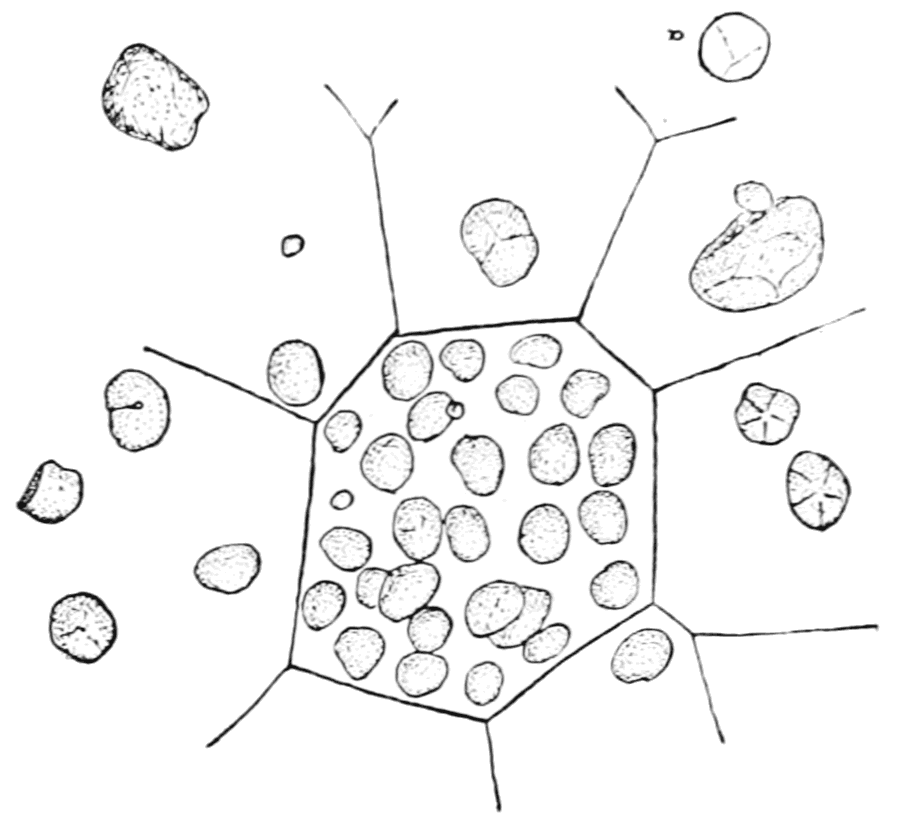

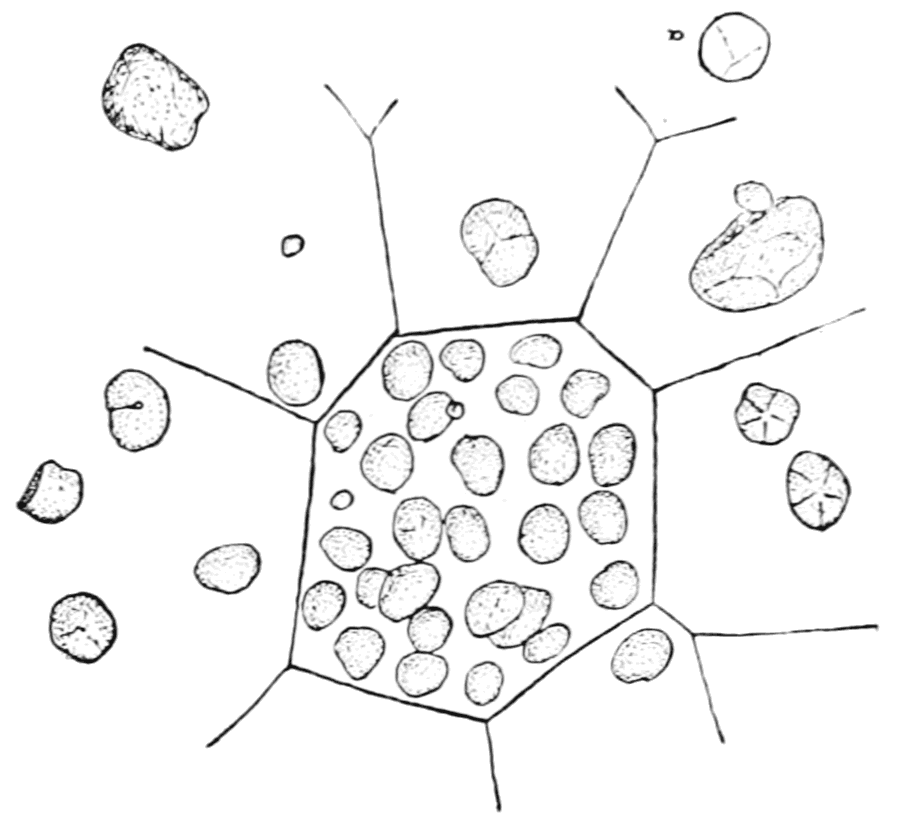

Thomas Harrison Montgomery Jr. described the morphology of the

nucleolus

The nucleolus (; : nucleoli ) is the largest structure in the cell nucleus, nucleus of eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis. The nucleolus also participates in the formation of signa ...

, an organelle within the nucleus, which has subsequently been shown to form through intracellular phase separation.

WB Hardy linked formation of biological

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s with phase separation in his study of

globulins

The globulins are a family of globular proteins that have higher molecular weights than albumins and are insoluble in pure water but dissolve in dilute salt solutions. Some globulins are produced in the liver, while others are made by the immun ...

, stating that: "The globulin is dispersed in the solvent as particles which are the colloid particles and which are so large as to form an internal phase", and further contributed to the basic physical description of oil-water phase separation.

Colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

as a driving force in cellular organisation appealed strongly to

Stephane Leduc, who wrote in his influential 1911 book ''The Mechanism of Life'': "Hence the study of life may be best begun by the study of those physico-chemical phenomena which result from the contact of two different liquids. Biology is thus but a branch of the physico-chemistry of liquids; it includes the study of electrolytic and colloidal solutions, and of the molecular forces brought into play by solution, osmosis, diffusion, cohesion, and crystallization."

The

primordial soup

Primordial soup, also known as prebiotic soup and Haldane soup, is the hypothetical set of conditions present on the Earth around 3.7 to 4.0 billion years ago. It is an aspect of the heterotrophic theory (also known as the Oparin–Haldane hypothes ...

theory of the origin of life, proposed by

Alexander Oparin in Russian in 1924 (published in English in 1936)

and by

J.B.S. Haldane in 1929, suggested that life was preceded by the formation of what Haldane called a "hot dilute soup" of "

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al organic substances", and which Oparin referred to as '

coacervates' (after de Jong) – particles composed of two or more

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s which might be protein, lipid or nucleic acid. These ideas strongly influenced the subsequent work of

Sidney W. Fox on proteinoid microspheres.

Support from other disciplines

When cell biologists largely abandoned

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al phase separation, it was left to relative outsiders – agricultural scientists and physicists – to make further progress in the study of phase separating biomolecules in cells.

Beginning in the early 1970s, Harold M Farrell Jr. at the US Department of Agriculture developed a

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

model for milk

casein

Casein ( , from Latin ''caseus'' "cheese") is a family of related phosphoproteins (CSN1S1, αS1, aS2, CSN2, β, K-casein, κ) that are commonly found in mammalian milk, comprising about 80% of the proteins in cow's milk and between 20% and 60% of ...

micelles that form within mammary gland cells before secretion as milk.

Also in the 1970s, physicists Tanaka & Benedek at MIT identified phase-separation behaviour of

gamma-crystallin proteins from lens

epithelial

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of man ...

cells and

cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens (anatomy), lens of the eye that leads to a visual impairment, decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or ...

s in solution,

which Benedek called protein condensation.

In the 1980s and 1990s,

Athene Donald's

polymer physics Polymer physics is the field of physics that studies polymers, their fluctuations, mechanical properties, as well as the kinetics of reactions involving degradation of polymers and polymerisation of monomers.P. Flory, ''Principles of Polymer Che ...

lab in Cambridge extensively characterised

phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

s /

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

of starch granules from the

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

of plant cells, which behave as

liquid crystal

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as i ...

s.

In 1991,

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes received the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing a generalized theory of phase transitions with particular applications to describing ordering and phase transitions in polymers. Unfortunately,

de Gennes wrote in ''Nature'' that

polymers

A polymer () is a substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, b ...

should be distinguished from other types of

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s, even though they can display similar clustering and

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

behaviour, a stance that has been reflected in the reduced usage of the term

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

to describe the higher-order association behaviour of

biopolymers

Biopolymers are natural polymers produced by the cells of living organisms. Like other polymers, biopolymers consist of monomeric units that are covalently bonded in chains to form larger molecules. There are three main classes of biopolymers, ...

in modern cell biology and

molecular self-assembly

In chemistry and materials science, molecular self-assembly is the process by which molecules adopt a defined arrangement without guidance or management from an outside source. There are two types of self-assembly: intermolecular and intramolec ...

.

Phase separation revisited

Advances in

confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy, most frequently confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) or laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM), is an optical imaging technique for increasing optical resolution and contrast (vision), contrast of a micrograph by me ...

at the end of the 20th century identified

proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, re ...

,

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

or

carbohydrates

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ma ...

localising to many non-membrane bound cellular compartments within the

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

or

nucleus which were variously referred to as 'puncta/dots',

'

signalosomes',

'

granules',

'

bodies', '

assemblies',

'

paraspeckles', '

purinosomes',

'

inclusions', '

aggregates' or '

factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. Th ...

'. During this time period (1995-2008) the concept of

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

was re-borrowed from

colloidal chemistry

Interface and colloid science is an interdisciplinary intersection of branches of chemistry, physics, nanoscience and other fields dealing with ''colloids'', heterogeneous systems consisting of a mechanical mixture of particles between 1 nm ...

&

polymer physics Polymer physics is the field of physics that studies polymers, their fluctuations, mechanical properties, as well as the kinetics of reactions involving degradation of polymers and polymerisation of monomers.P. Flory, ''Principles of Polymer Che ...

and proposed to underlie both

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

ic and

nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

compartmentalization.

Since 2009, further evidence for biomacromolecules undergoing intracellular

phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

s (

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

) has been observed in many different contexts, both within cells and in reconstituted ''in vitro'' experiments.

The newly coined term "biomolecular condensate"

refers to biological polymers (as opposed to synthetic

polymers

A polymer () is a substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, b ...

) that undergo

self assembly via clustering to increase the local concentration of the assembling components, and is analogous to the physical definition of

condensation

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor ...

.

In physics,

condensation

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor ...

typically refers to a gas–liquid

phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

.

In biology the term 'condensation' is used much more broadly and can also refer to liquid–liquid

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

to form

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al

emulsions

An emulsion is a mixture of two or more liquids that are normally immiscible (unmixable or unblendable) owing to liquid-liquid phase separation. Emulsions are part of a more general class of two-phase systems of matter called colloids. Althoug ...

or

liquid crystal

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as i ...

s within cells, and liquid–solid

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

to form

gels,

, or

suspensions within cells as well as liquid-to-solid

phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

s such as

DNA condensation

DNA condensation refers to the process of compacting DNA molecules ''in vitro'' or ''in vivo''. Mechanistic details of DNA packing are essential for its functioning in the process of gene regulation in living systems. Condensed DNA often has surpr ...

during

prophase

Prophase () is the first stage of cell division in both mitosis and meiosis. Beginning after interphase, DNA has already been replicated when the cell enters prophase. The main occurrences in prophase are the condensation of the chromatin retic ...

of the cell cycle or protein condensation of crystallins in

cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens (anatomy), lens of the eye that leads to a visual impairment, decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or ...

s.

With this in mind, the term 'biomolecular condensates' was deliberately introduced to reflect this breadth (see below). Since biomolecular condensation generally involves oligomeric or polymeric interactions between an indefinite number of components, it is generally considered distinct from formation of smaller stoichiometric protein complexes with defined numbers of subunits, such as viral capsids or the proteasome – although both are examples of spontaneous

molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, ...

self-assembly

Self-assembly is a process in which a disordered system of pre-existing components forms an organized structure or pattern as a consequence of specific, local interactions among the components themselves, without external direction. When the ...

or

self-organisation

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order and disorder, order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spont ...

.

Mechanistically, it appears that the conformational landscape (in particular, whether it is enriched in extended disordered states) and multivalent interactions between

intrinsically disordered proteins

In molecular biology, an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) is a protein that lacks a fixed or ordered protein tertiary structure, three-dimensional structure, typically in the absence of its macromolecular interaction partners, such as other ...

(including cross-beta polymerisation),

and/or

protein domains

In molecular biology, a protein domain is a region of a protein's polypeptide chain that is self-stabilizing and that folds independently from the rest. Each domain forms a compact folded three-dimensional structure. Many proteins consist of se ...

that induce head-to-tail oligomeric or polymeric clustering,

might play a role in phase separation of proteins.

Examples

Many examples of biomolecular condensates have been characterized in the

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

and the

nucleus that are thought to arise by either liquid–liquid or liquid–solid phase separation.

Cytoplasmic condensates

*

Lewy bodies

*

Stress granule

*

P-body

*

Germline P-granules –

oskar

*

Starch granules

*

Glycogen granules

*Frodosomes (

Dact1)

*

Corneal lens formation and

cataracts

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens of the eye that leads to a decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or double vision, halos around ligh ...

* Other

cytoplasmic inclusions such as pigment granules or cytoplasmic crystals

* Purinosomes

* Misfolded

protein aggregation

In molecular biology, protein aggregation is a phenomenon in which intrinsically disordered proteins, intrinsically-disordered or mis-folded proteins aggregate (i.e., accumulate and clump together) either intra- or extracellularly. Protein aggre ...

such as

amyloid fibrils or mutant Haemoglobin S (HbS) fibres in

sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD), also simply called sickle cell, is a group of inherited Hemoglobinopathy, haemoglobin-related blood disorders. The most common type is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia results in an abnormality in the ...

*

Signalosomes, such as the

supramolecular assemblies in the

Wnt signaling pathway

In cellular biology, the Wnt signaling pathways are a group of signal transduction pathways which begin with proteins that pass signals into a cell through cell surface receptors. The name Wnt, pronounced "wint", is a portmanteau created from the ...

.

* It can also be argued that

cytoskeletal filaments form by a polymerisation process similar to phase separation, except ordered into filamentous networks instead of amorphous droplets or granules.

*Bacteria Ribonucleoprotein Bodies (BR-bodies)- In recent studies it has been shown that bacteria RNA degradosomes can assemble into phase-separated structures, termed bacterial ribonucleoprotein bodies (BR-bodies), with many analogous properties to eukaryotic processing bodies (P-bodies) and stress granules.

*FLOE1 granules: FLOE1 is a prion-like seed-specific protein that controls plant seed germination via phase separation into biomolecular condensates.

*Perinuclear compartment

Nuclear condensates

*

Nucleolus

The nucleolus (; : nucleoli ) is the largest structure in the cell nucleus, nucleus of eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis. The nucleolus also participates in the formation of signa ...

*

Nuclear speckle

*

Cajal body

*

Paraspeckle

*

Synaptonemal complex

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is a protein structure that forms between homologous chromosomes (two pairs of sister chromatids) during meiosis and is thought to mediate synapsis and recombination during prophase I during meiosis in eukaryotes ...

Other nuclear structures including

heterochromatin

Heterochromatin is a tightly packed form of DNA or '' condensed DNA'', which comes in multiple varieties. These varieties lie on a continuum between the two extremes of constitutive heterochromatin and facultative heterochromatin. Both play a rol ...

form by mechanisms similar to phase separation, so can also be classified as biomolecular condensates.

Plasma membrane associated condensates

* Membrane protein, or membrane-associated protein, clustering at neurological

synapses

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

, cell-cell

tight junctions, or other membrane domains.

Secreted extracellular condensates

* Secreted

thyroglobulin

Thyroglobulin (Tg) is a 660 kDa, dimeric glycoprotein produced by the follicular cells of the thyroid and used entirely within the thyroid gland. Tg is secreted and accumulated at hundreds of grams per litre in the extracellular compartment ...

colloid and

colloid nodules of the

thyroid

The thyroid, or thyroid gland, is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, it is a butterfly-shaped gland located in the neck below the Adam's apple. It consists of two connected lobes. The lower two thirds of the lobes are connected by ...

gland

* Secreted

casein

Casein ( , from Latin ''caseus'' "cheese") is a family of related phosphoproteins (CSN1S1, αS1, aS2, CSN2, β, K-casein, κ) that are commonly found in mammalian milk, comprising about 80% of the proteins in cow's milk and between 20% and 60% of ...

'micelles' of the mammary gland

* Serum

albumin

Albumin is a family of globular proteins, the most common of which are the serum albumins. All of the proteins of the albumin family are water- soluble, moderately soluble in concentrated salt solutions, and experience heat denaturation. Alb ...

and

globulins

The globulins are a family of globular proteins that have higher molecular weights than albumins and are insoluble in pure water but dissolve in dilute salt solutions. Some globulins are produced in the liver, while others are made by the immun ...

* Secreted

lysozyme

Lysozyme (, muramidase, ''N''-acetylmuramide glycanhydrolase; systematic name peptidoglycan ''N''-acetylmuramoylhydrolase) is an antimicrobial enzyme produced by animals that forms part of the innate immune system. It is a glycoside hydrolase ...

Lipid-enclosed organelles and

lipoprotein

A lipoprotein is a biochemical assembly whose primary function is to transport hydrophobic lipid (also known as fat) molecules in water, as in blood plasma or other extracellular fluids. They consist of a triglyceride and cholesterol center, sur ...

s are not considered condensates

Typical

organelles or

endosomes enclosed by a

lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes form a continuous barrier around all cell (biology), cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses a ...

are not considered biomolecular condensates. In addition,

lipid droplets are surrounded by a lipid monolayer in the cytoplasm, or in

milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

, or in tears,

so appear to fall under the 'membrane bound' category. Finally, secreted

LDL and

HDL lipoprotein

A lipoprotein is a biochemical assembly whose primary function is to transport hydrophobic lipid (also known as fat) molecules in water, as in blood plasma or other extracellular fluids. They consist of a triglyceride and cholesterol center, sur ...

particles are also enclosed by a lipid monolayer. The formation of these structures involves

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

to from

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al

micelle

A micelle () or micella () ( or micellae, respectively) is an aggregate (or supramolecular assembly) of surfactant amphipathic lipid molecules dispersed in a liquid, forming a colloidal suspension (also known as associated colloidal system). ...

s or

liquid crystal

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as i ...

bilayers, but they are not classified as biomolecular condensates, as this term is reserved for non-membrane bound organelles.

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) in biology

Liquid biomolecular condensates

Liquid–liquid

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

(LLPS) generates a subtype of

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

known as an

mulsion that can

coalesce to form large droplets within a liquid. Ordering of molecules during liquid–liquid

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

can generate

liquid crystal

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as i ...

s rather than emulsions. In cells, LLPS produces a liquid subclass of biomolecular condensate that can behave as either an emulsion or liquid crystal.

The term biomolecular condensates was introduced in the context of intracellular assemblies as a convenient but non-exclusionary term to describe non-stoichiometric assemblies of biomolecules.

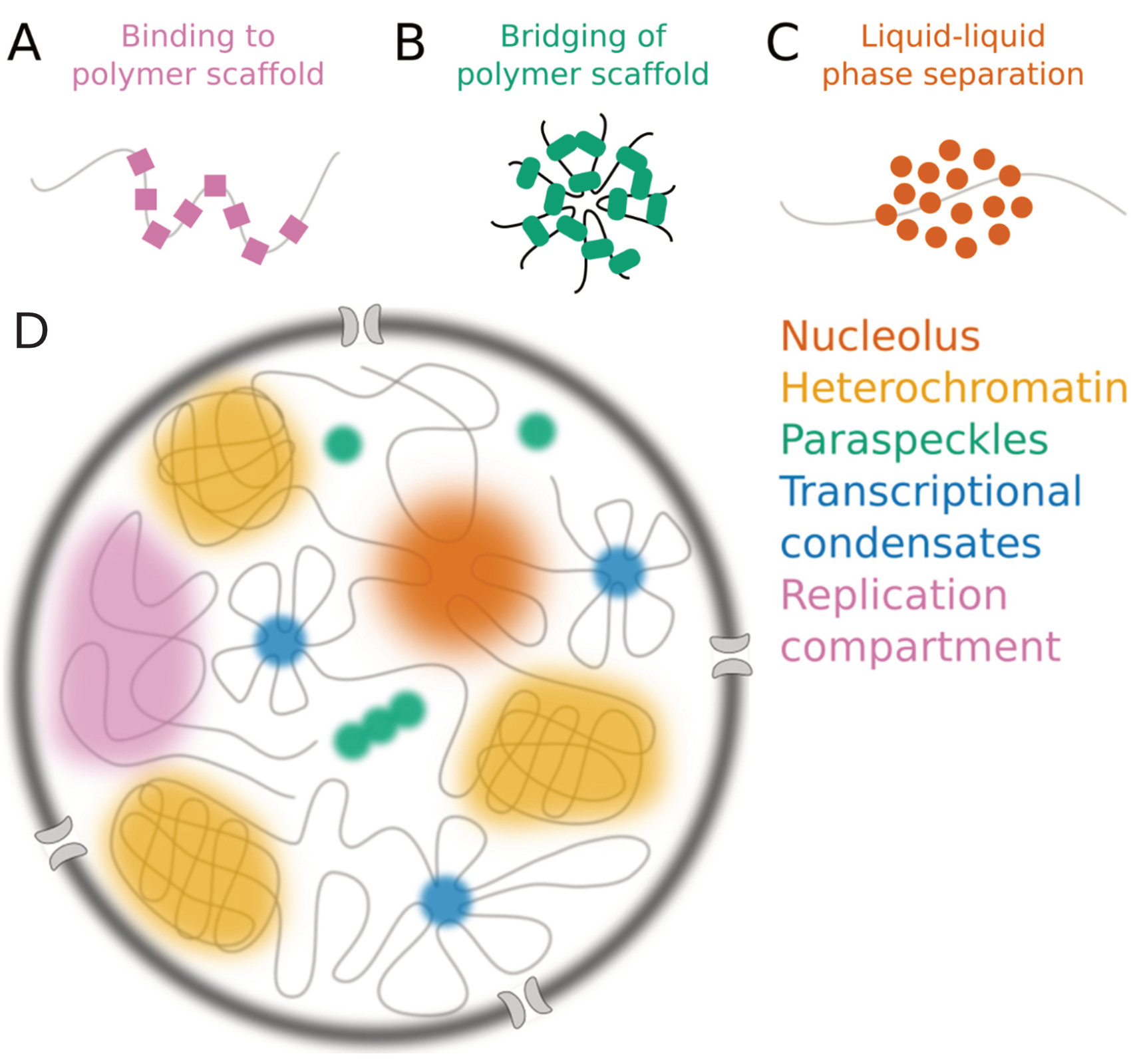

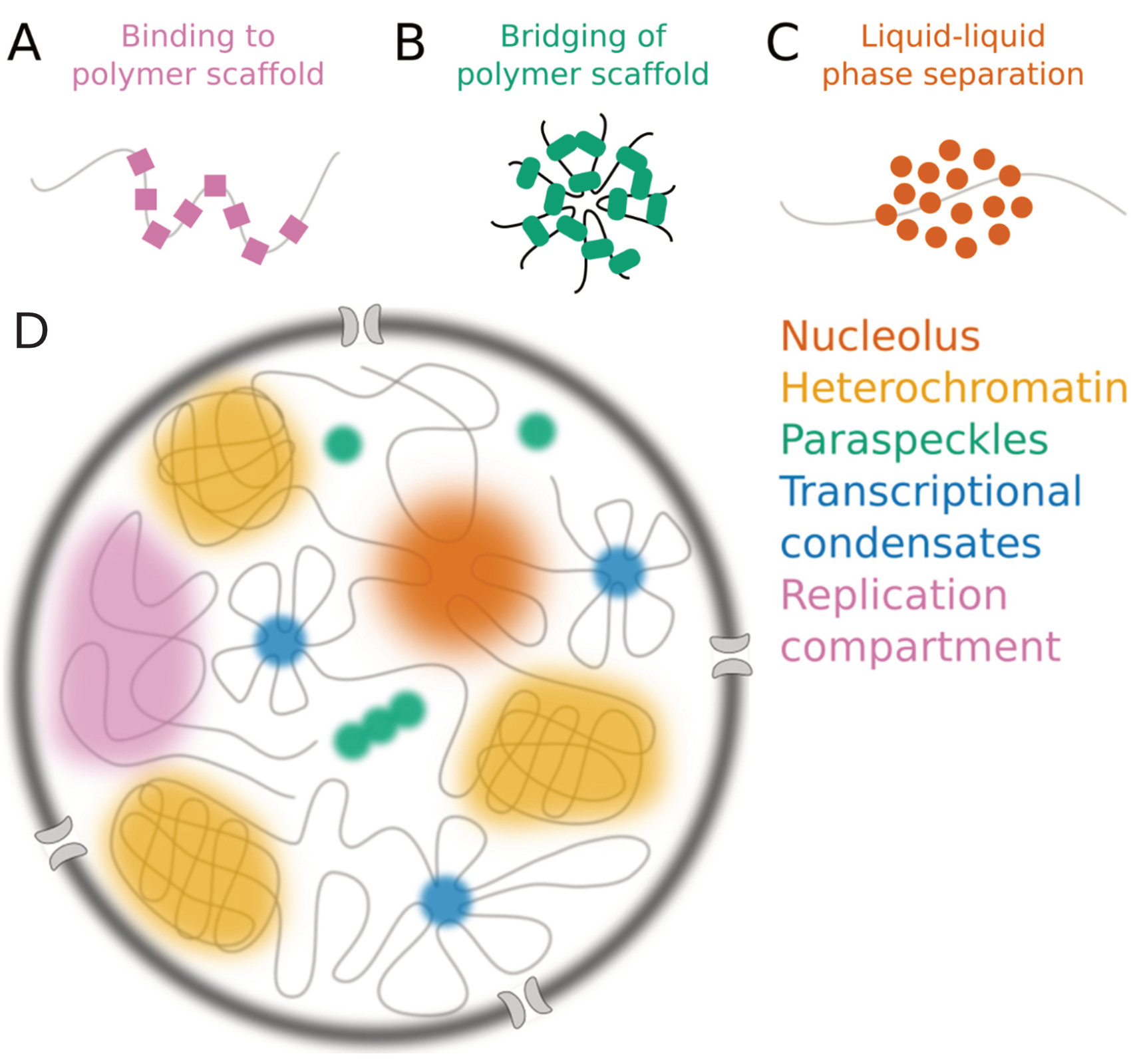

The choice of language here is specific and important. It has been proposed that many biomolecular condensates form through liquid–liquid

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

(LLPS) to form

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

al

emulsions

An emulsion is a mixture of two or more liquids that are normally immiscible (unmixable or unblendable) owing to liquid-liquid phase separation. Emulsions are part of a more general class of two-phase systems of matter called colloids. Althoug ...

or

liquid crystal

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as i ...

s in living organisms, as opposed to liquid–solid

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

to form

crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

s/

aggregates in

gels,

or

suspensions within cells or extracellular secretions.

However, unequivocally demonstrating that a cellular body forms through liquid–liquid phase separation is challenging,

because different material states (liquid vs. gel vs. solid) are not always easy to distinguish in living cells. The term "biomolecular condensate" directly addresses this challenge by making no assumption regarding either the physical mechanism through which assembly is achieved, nor the material state of the resulting assembly. Consequently, cellular bodies that form through liquid–liquid phase separation are a subset of biomolecular condensates, as are those where the physical origins of assembly are unknown. Historically, many cellular non-membrane bound compartments identified microscopically fall under the broad umbrella of biomolecular condensates.

In physics, phase separation can be classified into the following types of

colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

, of which biomolecular condensates are one example:

In biology, the most relevant forms of

phase separation

Phase separation is the creation of two distinct Phase (matter), phases from a single homogeneous mixture. The most common type of phase separation is between two immiscible liquids, such as oil and water. This type of phase separation is kn ...

are either liquid–liquid or liquid–solid, although there have been reports of

gas vesicles surrounded by a phase separated protein coat in the cytoplasm of some microorganisms.

Condensate microenvironment

The condensate microenvironment refers to the distinct internal physical and chemical conditions within biomolecular condensates that influence molecular behavior and biochemical activity

. These environments can differ markedly from the surrounding cellular milieu in terms of material property

, pH

, and chemical property

. Rather than acting solely as passive concentration hubs, condensates modulate their internal milieu to promote selective partitioning, regulate reaction kinetics, and enable context-specific biological functions.

Experimental studies have revealed several mechanisms by which condensate microenvironments operate. The material properties of condensates have been linked to condensate composition and functions

. Nucleolar condensates have been shown to maintain internal pH gradients that influence RNA processing and protein composition

. Other studies have demonstrated that different nuclear condensates exhibit distinct solvent characteristics, shaping the partitioning behavior of small molecules and biochemical cofactors

.

Further direct evidence comes from experiments using synthetic tools to manipulate condensate material properties. One study introduced a genetically encoded peptide, killswitch

, that selectively arrests condensate dynamics without disrupting their scaffolds, enabling controlled perturbation of condensate material property in live cells. This intervention altered the protein composition of transcriptional condensates and impaired their biological activity. In mouse leukemia model driven by fusion oncoprotein, condensate arrest suppressed target gene expression and inhibited cell proliferation. These findings provide mechanistic support for the functional relevance of the condensate microenvironment.

Together, these studies establish the condensate microenvironment as a key mechanism in the regulation of biochemical specificity, localization, and activity within cells.

Wnt signalling

One of the first discovered examples of a highly dynamic intracellular liquid biomolecular condensate with a clear physiological function were the supramolecular complexes (Wnt

signalosomes) formed by components of the

Wnt signaling pathway

In cellular biology, the Wnt signaling pathways are a group of signal transduction pathways which begin with proteins that pass signals into a cell through cell surface receptors. The name Wnt, pronounced "wint", is a portmanteau created from the ...

.

The

Dishevelled

Dishevelled (Dsh) is a family of proteins involved in canonical and non-canonical Wnt signalling pathways. Dsh (Dvl in mammals) is a cytoplasmic phosphoprotein that acts directly downstream of frizzled receptors. It takes its name from its initi ...

(Dsh or Dvl) protein undergoes clustering in the cytoplasm via its DIX domain, which mediates protein clustering (polymerisation) and phase separation, and is important for signal transduction.

The Dsh protein functions both in planar polarity and Wnt signalling, where it recruits another supramolecular complex (the Axin complex) to Wnt receptors at the plasma membrane. The formation of these Dishevelled and Axin containing droplets is conserved across metazoans, including in ''

Drosophila

''Drosophila'' (), from Ancient Greek δρόσος (''drósos''), meaning "dew", and φίλος (''phílos''), meaning "loving", is a genus of fly, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or p ...

'', ''

Xenopus

''Xenopus'' () (Gk., ξενος, ''xenos'' = strange, πους, ''pous'' = foot, commonly known as the clawed frog) is a genus of highly aquatic frogs native to sub-Saharan Africa. Twenty species are currently described with ...

'', and human cells.

P granules

Another example of liquid droplets in cells are the germline P granules in ''

Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a Hybrid word, blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''r ...

''.

These granules separate out from the cytoplasm and form droplets, as oil does from water. Both the granules and the surrounding cytoplasm are liquid in the sense that they flow in response to forces, and two of the granules can coalesce when they come in contact. When (some of) the molecules in the granules are studied (via

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) is a method for determining the kinetics of diffusion through tissue or cells. It is capable of quantifying the two-dimensional lateral diffusion of a molecularly thin film containing fluorescently ...

), they are found to rapidly turnover in the droplets, meaning that molecules diffuse into and out of the granules, just as expected in a

liquid

Liquid is a state of matter with a definite volume but no fixed shape. Liquids adapt to the shape of their container and are nearly incompressible, maintaining their volume even under pressure. The density of a liquid is usually close to th ...

droplet. The droplets can also grow to be many molecules across (micrometres)

Studies of droplets of the ''

Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a Hybrid word, blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''r ...

'' protein LAF-1 ''in vitro'' also show liquid-like behaviour, with an apparent

viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent drag (physics), resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for e ...

Pa s. This is about a ten thousand times that of water at room temperature, but it is small enough to enable the LAF-1 droplets to flow like a liquid. Generally, interaction strength (

affinity

Affinity may refer to:

Commerce, finance and law

* Affinity (law), kinship by marriage

* Affinity analysis, a market research and business management technique

* Affinity Credit Union, a Saskatchewan-based credit union

* Affinity Equity Pa ...

) and valence (number of binding sites)

of the phase separating biomolecules influence their condensates viscosity, as well as their overall tendency to phase separate.

Liquid–liquid phase separation in human disease

Growing evidence suggests that anomalies in biomolecular condensates formation can lead to a number of human pathologies such as cancer and

neurodegenerative diseases

A neurodegenerative disease is caused by the progressive loss of neurons, in the process known as neurodegeneration. Neuronal damage may also ultimately result in their death. Neurodegenerative diseases include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, mul ...

.

Biomolecular condensates in plants

Biomolecular condensates can play other roles in plants besides the compartmentalization of biochemical processes. They can integrate environmental cues and modulate plant development in response, influencing processes like floral transition. They achieve this by sequestering interacting components, enhancing dwell time, and interacting with cytoplasmic properties in response to environmental changes. They have shown to be involved also in

autophagy

Autophagy (or autophagocytosis; from the Greek language, Greek , , meaning "self-devouring" and , , meaning "hollow") is the natural, conserved degradation of the cell that removes unnecessary or dysfunctional components through a lysosome-depe ...

,

RNA silencing

RNA silencing or RNA interference refers to a family of gene silencing effects by which gene expression is negatively regulated by non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs. RNA silencing may also be defined as sequence-specific regulation of gene expressi ...

, and plant immunity.

NAtural

Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) are mixtures of natural compounds such as amino acids, sugars, choline, and organic acids that can solubilize high amounts of natural products. NADES are hypothesized to be the third liquid phase in plants, due to their presence in plant cells together with their ability to improve and stabilise enzymatic reactions, as well as enhance extraction and dissolution of natural products. They are speculated to facilitate the formation of phase-separated inclusions, aiding in the storage and transport of specific metabolites

such as

anthocyanin

Anthocyanins (), also called anthocyans, are solubility, water-soluble vacuole, vacuolar pigments that, depending on their pH, may appear red, purple, blue, or black. In 1835, the German pharmacist Ludwig Clamor Marquart named a chemical compou ...

s,

dhurrin, and

vanillin

Vanillin is an organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a phenolic aldehyde. Its functional groups include aldehyde, hydroxyl, and ether. It is the primary component of the ethanolic extract of the vanilla bean. Synthetic vanillin ...

.

Synthetic biomolecular condensates

Biomolecular condensates can be

synthesized for a number of purposes. Synthetic biomolecular condensates are inspired by

endogenous

Endogeny, in biology, refers to the property of originating or developing from within an organism, tissue, or cell.

For example, ''endogenous substances'', and ''endogenous processes'' are those that originate within a living system (e.g. an ...

biomolecular condensates, such as

nucleoli

The nucleolus (; : nucleoli ) is the largest structure in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis. The nucleolus also participates in the formation of signal recognition particles and plays a ro ...

,

P bodies, and

stress granules, which are essential to normal

cellular organization and function.

Synthetic condensates are an important tool in

synthetic biology

Synthetic biology (SynBio) is a multidisciplinary field of science that focuses on living systems and organisms. It applies engineering principles to develop new biological parts, devices, and systems or to redesign existing systems found in nat ...

, and have a wide and growing range of applications. Engineered synthetic condensates allow for probing cellular organization, and enable the creation of novel functionalized biological materials, which have the potential to serve as

drug delivery

Drug delivery involves various methods and technologies designed to transport pharmaceutical compounds to their target sites helping therapeutic effect. It involves principles related to drug preparation, route of administration, site-specif ...

platforms and

therapeutic agents.

Design and control

Despite the dynamic nature and lack of

binding specificity that govern the formation of biomolecular condensates, synthetic condensates can still be engineered to exhibit different behaviors. One popular way to conceptualize condensate interactions and aid in design is through the "sticker-spacer" framework. Multivalent interaction sites, or "stickers", are separated by "spacers", which provide the

conformational flexibility and physically separate individual interaction modules from one another. Proteins regions identified as 'stickers' usually consist of

Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) that act as "sticky"

biopolymer

Biopolymers are natural polymers produced by the cells of living organisms. Like other polymers, biopolymers consist of monomeric units that are covalently bonded in chains to form larger molecules. There are three main classes of biopolymers, ...

s via short patches of interacting residues patterned along their unstructured chain, which collectively promote

LLPS. By modifying the sticker-spacer framework, i.e. the

polypeptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty ...

and RNA sequences as well as their mixture compositions, the material properties (

viscous

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for example, syrup h ...

and

elastic

Elastic is a word often used to describe or identify certain types of elastomer, Elastic (notion), elastic used in garments or stretch fabric, stretchable fabrics.

Elastic may also refer to:

Alternative name

* Rubber band, ring-shaped band of rub ...

regimes) of condensates can be tuned to design novel condensates.

Other tools outside of tuning the sticker-spacer framework can be used to give new functionality and to allow for high temporal and spatial control over synthetic condensates. One way to gain temporal control over the formation and

dissolution of biomolecular condensates is by using

optogenetic tools. Several different systems have been developed which allow for control of condensate formation and dissolution which rely on

chimeric protein expression, and light or small molecule activation. In one system, proteins are expressed in a

cell which contain light-activated

oligomer

In chemistry and biochemistry, an oligomer () is a molecule that consists of a few repeating units which could be derived, actually or conceptually, from smaller molecules, monomers.Quote: ''Oligomer molecule: A molecule of intermediate relativ ...

ization domains fused to IDRs. Upon irradiation with a specific

wavelength of light, the oligomerization domains bind each other and form a 'core', which also brings multiple IDRs close together because they are fused to the oligomerization domains. The recruitment of multiple IDRs effectively creates a new biopolymer with increased

valency. This increased valency allows for the IDRs to form multivalent interactions and trigger

LLPS. When the activation light is stopped, the oligomerization domains disassemble, causing the dissolution of the condensate. A similar system achieves the same temporal control of condensate formation by using light-sensitive 'caged'

dimerizers. In this case, light-activation removes the dimerizer cage, allowing it to recruit IDRs to multivalent cores, which then triggers phase separation. Light-activation of a different wavelength results in the dimerizer being cleaved, which then releases the IDRs from the core and consequentially dissolves the condensate. This dimerizer system requires significantly reduced amounts of

laser light

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

to operate, which is advantageous because high intensity light can be toxic to cells.

Optogenetic systems can also be modified to gain spatial control over the formation of condensates. Multiple approaches have been developed to do so. In one approach,

[Y. Shin, Y. C. Chang, D. S. Lee, J. Berry, D. W. Sanders, P. Ronceray, N. S.Wingreen, M. Haataja, and C. P. Brangwynne, “Liquid Nuclear Condensates Mechanically Sense and Restructure the Genome,” Cell, vol. 175, no. 6, pp. 1481–1491.e13, 2018.] which localizes condensates to specific

genomic regions, core proteins are fused to proteins such as TRF1 or catalytically dead

Cas9

Cas9 (CRISPR associated protein 9, formerly called Cas5, Csn1, or Csx12) is a 160 dalton (unit), kilodalton protein which plays a vital role in the immunological defense of certain bacteria against DNA viruses and plasmids, and is heavily utili ...

, which bind specific genomic loci. When

oligomer

In chemistry and biochemistry, an oligomer () is a molecule that consists of a few repeating units which could be derived, actually or conceptually, from smaller molecules, monomers.Quote: ''Oligomer molecule: A molecule of intermediate relativ ...

ization is trigger by light activation, phase separation is preferentially induced on the specific genomic region which is recognized by fusion protein. Because condensates of the same composition can interact and fuse with each other, if they are tethered to specific regions of the

genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, condensates can be used to alter the spatial organization of the genome, which can have effects on gene expression.

As biochemical reactors

Synthetic condensates offer a way to probe cellular function and organization with high spatial and temporal control, but can also be used to modify or add functionality to the

cell. One way this is accomplished is by modifying the

condensate networks to include

binding site

In biochemistry and molecular biology, a binding site is a region on a macromolecule such as a protein that binds to another molecule with specificity. The binding partner of the macromolecule is often referred to as a ligand. Ligands may includ ...

s for other

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s of interest, thus allowing the condensate to serve as a scaffold for protein release or recruitment.

[M. Yoshikawa and S. Tsukiji, “Modularly Built Synthetic Membraneless Organelles Enabling Targeted Protein Sequestration and Release,” Biochemistry, Oct 2021.] These binding sites can be modified to be sensitive to light activation or small molecule addition, thus giving temporal control over the recruitment of a specific protein of interest. By recruiting specific proteins to condensates,

reactants

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

can be concentrated to increase

reaction rate

The reaction rate or rate of reaction is the speed at which a chemical reaction takes place, defined as proportional to the increase in the concentration of a product per unit time and to the decrease in the concentration of a reactant per u ...

s or sequestered to inhibit reactivity. In addition to protein recruitment, condensates can also be designed which release proteins in response to certain stimuli. In this case, a protein of interest can be fused to a

scaffold protein via a photocleavable linker. Upon

irradiation

Irradiation is the process by which an object is exposed to radiation. An irradiator is a device used to expose an object to radiation, most often gamma radiation, for a variety of purposes. Irradiators may be used for sterilizing medical and p ...

, the linker is broken, and the protein is released from the condensate. Using these design principles, proteins can either be released to, or sequestered from, their native environment, allowing condensates to serve as a tool to alter the

biochemical

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, ...

activity of specific proteins with a high level of control.

Methods to study condensates

A number of experimental and computational methods have been developed to examine the physico-chemical properties and underlying molecular interactions of biomolecular condensates. Experimental approaches include phase separation assays using

bright-field imaging or

fluorescence microscopy

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. A fluorescence micro ...

, and

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) is a method for determining the kinetics of diffusion through tissue or cells. It is capable of quantifying the two-dimensional lateral diffusion of a molecularly thin film containing fluorescently ...

(FRAP), as well as

rheological analysis of phase-separated droplets. Computational approaches include coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations and

circuit topology

The circuit topology of a folded linear polymer refers to the arrangement of its intra-molecular contacts. Examples of linear polymers with intra-molecular contacts are nucleic acids and proteins. Proteins fold via the formation of contacts of v ...

analysis.

Coarse-grained molecular models

Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computer simulation method for analyzing the Motion (physics), physical movements of atoms and molecules. The atoms and molecules are allowed to interact for a fixed period of time, giving a view of the dynamics ( ...

and

Monte Carlo simulations have been extensively used to gain insights into the formation and the material properties of biomolecular condensates.

Although molecular models of different resolution have been employed,

modelling efforts have mainly focused on coarse-grained models of intrinsically disordered proteins, wherein amino acid residues are represented by single interaction sites.

Compared to more detailed molecular descriptions, residue-level models provide high computational efficiency, which enables simulations to cover the long length and time scales required to study phase separation. Moreover, the resolution of these models is sufficiently detailed to capture the dependence on amino acid sequence of the properties of the system.

Several residue-level models of intrinsically disordered proteins have been developed in recent years. Their common features are (i) the absence of an explicit representation of solvent molecules and salt ions, (ii) a mean-field description of the electrostatic interactions between charged residues (see

Debye–Hückel theory), and (iii) a set of "stickiness" parameters which quantify the strength of the attraction between pairs of amino acids. In the development of most residue-level models, the stickiness parameters have been derived from

hydrophobicity scales or from a bioinformatic analysis of crystal structures of folded proteins.

Further refinement of the parameters has been achieved through iterative procedures which maximize the agreement between model predictions and a set of experiments,

or by leveraging data obtained from all-atom molecular dynamics simulations.

Residue-level models of intrinsically disordered proteins have been validated by direct comparison with experimental data, and their predictions have been shown to be accurate across diverse amino acid sequences.

Examples of experimental data used to validate the models are

radii of gyration of isolated chains and

saturation concentrations, which are threshold protein concentrations above which phase separation is observed.

Although intrinsically disordered proteins often play important roles in condensate formation,

many biomolecular condensates contain

multi-domain proteins constituted by folded domains connected by intrinsically disordered regions. Current residue-level models are only applicable to the study of condensates of intrinsically disordered proteins and nucleic acids.

Including an accurate description of the folded domains in these models will considerably widen their applicability.

Mechanical analysis of biomolecular condensates

To identify liquid-liquid phase separation and formation of condensate liquid droplets, one needs to demonstrate the liquid behaviors (viscoelasticity) of the condensates. Furthermore, mechanical processes are key to condensate related diseases, as pathological changes to condensates can lead to their solidification. Rheological methods are commonly used to demonstrate the liquid behavior of biomolecular condensates. These include active microrheological characterization by means of optical tweezers and scanning probe microscopy.

[Aida Naghilou, Oskar Armbruster, Alireza Mashaghi, Scanning probe microscopy elucidates gelation and rejuvenation of biomolecular condensates. (2024]

Link

/ref>

See also

* List of liquid–liquid phase separation databases

References

Further reading

* Ball, Philip, "A New Understanding of the Cell: Gloppy specks called biomolecular condensates are rewriting the story of how life works", ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it, with more than 150 Nobel Pri ...

'', vol. 332, no. 2 (February 2025), pp. 22–27. "Biomolecular condensates now seem to be a key part of how life gets its countless molecular components to coordinate and cooperate, to form committees that make the group decisions on which our very existence depends." (p. 24.)

*

*

*

*

{{refend

Organelles

In

In  The micellar theory of

The micellar theory of  Many examples of biomolecular condensates have been characterized in the

Many examples of biomolecular condensates have been characterized in the  *

*