Billy Hughes (footballer, Born 1918) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh

Hughes was born on 25 September 1862, at 7 Moreton Place,

Hughes was born on 25 September 1862, at 7 Moreton Place,

After finishing his initial apprenticeship, Hughes stayed on at St Stephen's as a teaching assistant. He had no interest in teaching as a career though, and also declined Matthew Arnold's offer to secure him a clerkship at

After finishing his initial apprenticeship, Hughes stayed on at St Stephen's as a teaching assistant. He had no interest in teaching as a career though, and also declined Matthew Arnold's offer to secure him a clerkship at

Hughes moved to

Hughes moved to

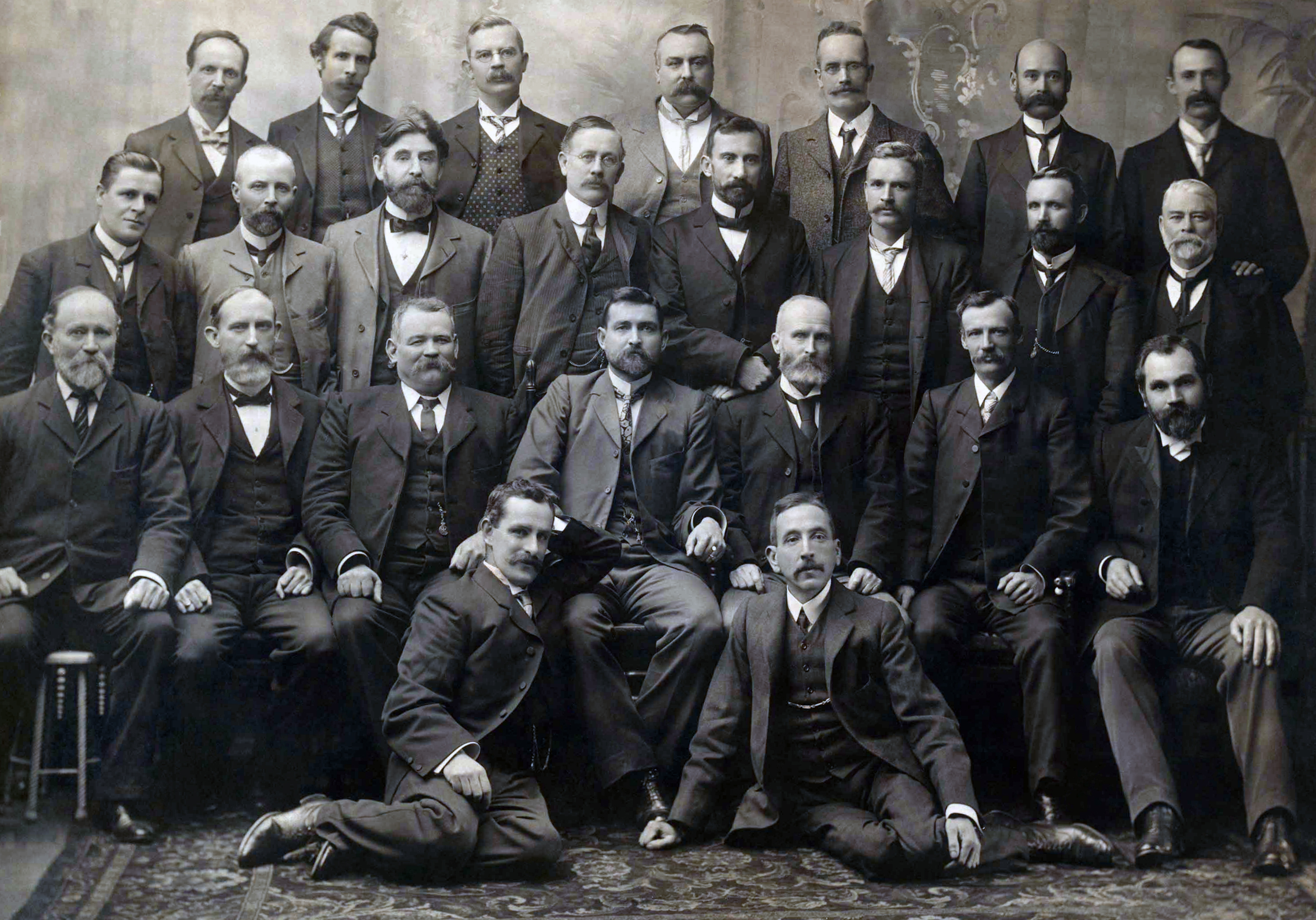

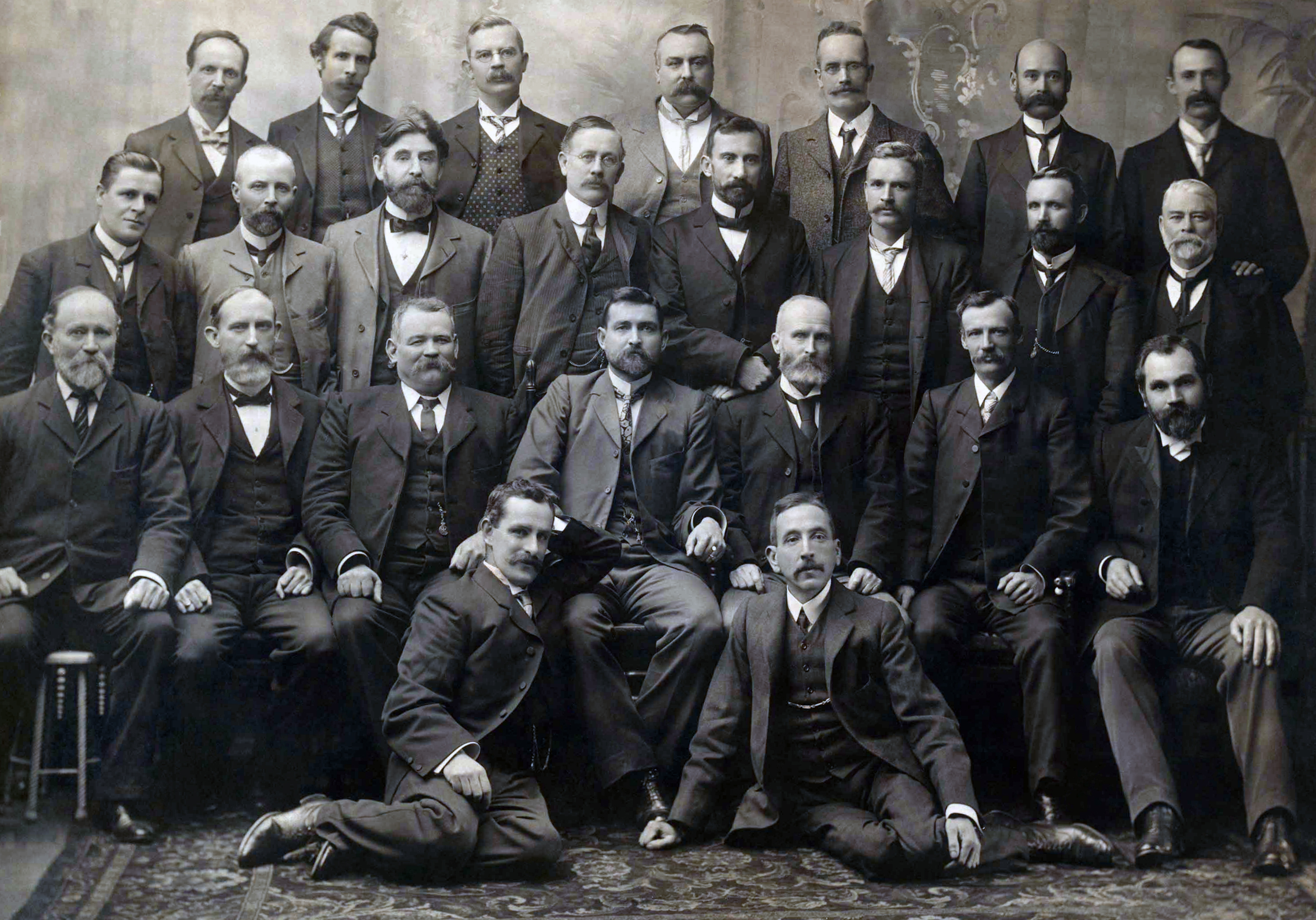

In 1901 Hughes was elected to the first federal Parliament as Labor MP for the

In 1901 Hughes was elected to the first federal Parliament as Labor MP for the  In 1911, he married Mary Campbell. He was Minister for External Affairs in

In 1911, he married Mary Campbell. He was Minister for External Affairs in

Following the

Following the

In 1919 Hughes, with former prime minister

In 1919 Hughes, with former prime minister

The UAP won a sweeping victory at the 1931 election. Lyons sent Hughes to represent Australia at the 1932 League of Nations Assembly in Geneva and in 1934 Hughes became Minister for Health and Repatriation in the

The UAP won a sweeping victory at the 1931 election. Lyons sent Hughes to represent Australia at the 1932 League of Nations Assembly in Geneva and in 1934 Hughes became Minister for Health and Repatriation in the

In February 1944, the parliamentary UAP voted to withdraw its members from the

In February 1944, the parliamentary UAP voted to withdraw its members from the

The only child from Hughes's second marriage was Helen Myfanwy Hughes, who was born in 1915 (a few months before he became prime minister). He doted upon her, calling her the "joy and light of my life", and was devastated by her death in childbirth in 1937, aged 21. Her son survived and was adopted by a friend of the family, with his grandfather contributing towards his upkeep. Because she was unmarried at the time, the circumstances of Helen's death were kept hidden and did not become generally known until 2004, when the ABC screened a programme presented by the actor

The only child from Hughes's second marriage was Helen Myfanwy Hughes, who was born in 1915 (a few months before he became prime minister). He doted upon her, calling her the "joy and light of my life", and was devastated by her death in childbirth in 1937, aged 21. Her son survived and was adopted by a friend of the family, with his grandfather contributing towards his upkeep. Because she was unmarried at the time, the circumstances of Helen's death were kept hidden and did not become generally known until 2004, when the ABC screened a programme presented by the actor

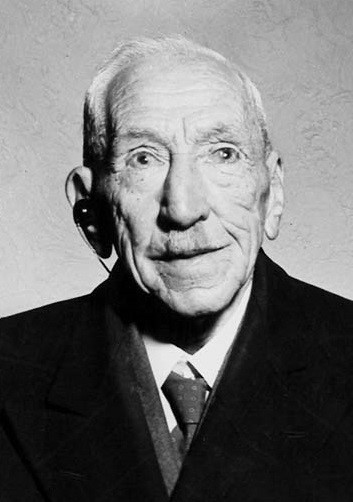

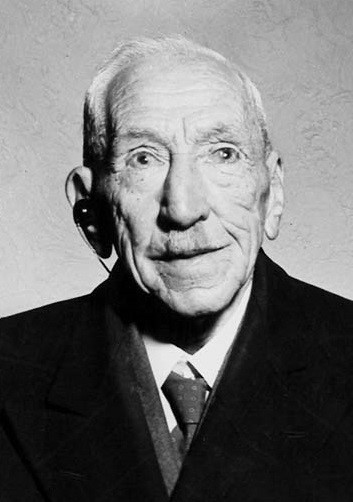

Hughes had a severe hearing loss that began when he was relatively young and worsened with age. He relied on a primitive electronic

Hughes had a severe hearing loss that began when he was relatively young and worsened with age. He relied on a primitive electronic

Billy Hughes at the National Film and Sound Archive

* , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Hughes, Billy Prime ministers of Australia 20th-century prime ministers of Australia Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian King's Counsel Ministers for foreign affairs of Australia Ministers for health of Australia Australian sailors Attorneys-general of Australia Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Liberal Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Australian Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Bendigo Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Bradfield Members of the Australian House of Representatives for North Sydney Members of the Australian House of Representatives for West Sydney Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Members of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia United Australia Party members of the Parliament of Australia British emigrants to Australia 1862 births 1952 deaths National Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Independent members of the Parliament of Australia Australian Party members of the Parliament of Australia Articles containing video clips Australian Anglicans Australian white nationalists Critics of the Catholic Church Leaders of the Australian Labor Party Leaders of the United Australia Party Leaders of the Nationalist Party of Australia Georgist politicians Royal Fusiliers soldiers Australian MPs 1901–1903 Australian MPs 1903–1906 Australian MPs 1906–1910 Australian MPs 1910–1913 Australian MPs 1913–1914 Australian MPs 1914–1917 Australian MPs 1917–1919 Australian MPs 1919–1922 Australian MPs 1922–1925 Australian MPs 1925–1928 Australian MPs 1928–1929 Australian MPs 1929–1931 Australian MPs 1931–1934 Australian MPs 1934–1937 Australian MPs 1937–1940 Australian MPs 1940–1943 Australian MPs 1943–1946 Australian MPs 1946–1949 Australian MPs 1949–1951 Australian MPs 1951–1954

prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics spanned several decades. He was a member of the federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch of Australia (represented by the governor ...

from the Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Wester ...

in 1901 until his death in 1952, and is the only person to have served as a parliamentarian for more than 50 years. He represented six political parties during his career, leading five, outlasting four, and being expelled from three.

Hughes was born in London to Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

parents. He emigrated to Australia at the age of 22, and became involved in the fledgling Australian labour movement. He was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament House ...

in 1894, as a member of the New South Wales Labor Party

The New South Wales Labor Party, officially known as the Australian Labor Party (New South Wales Branch) and commonly referred to simply as NSW Labor, is the New South Wales branch of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). The branch is the current ...

, and then transferred to the new federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch of Australia (represented by the governor ...

in 1901. Hughes combined his early political career with part-time legal studies, and was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1903. He first entered cabinet in 1904, in the short-lived Watson government

The Watson government was the third federal executive government of the Commonwealth of Australia. It was led by Prime Minister Chris Watson of the Australian Labor Party from 27 April 1904 to 18 August 1904. The Watson government was the first ...

, and was later the Attorney-General of Australia

The attorney-general of Australia (AG), also known as the Commonwealth attorney-general, is the minister of state and chief law officer of the Commonwealth of Australia charged with overseeing federal legal affairs and public security as the ...

in each of Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian ...

's governments. He was elected deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

in 1914.

Hughes became prime minister in October 1915, when Fisher retired due to ill health. The war was the dominant issue of the time, and his support for sending conscripted troops overseas caused a split within Labor ranks. Hughes and his supporters were expelled from the party in November 1916, but he was able to remain in power at the head of the new National Labor Party

The National Labor Party (NLP) was an Australian political party formed by Prime Minister Billy Hughes in November 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of ...

, which after a few months merged with the Liberals to form the Nationalist Party. His government was re-elected with large majorities at the 1917

Events

Below, the events of World War I have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 9 – WWI – Battle of Rafa: The last substantial Ottoman Army garrison on the Sinai Peninsula is captured by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's ...

and 1919 elections. Hughes established the forerunners of the Australian Federal Police

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) is the principal Federal police, federal law enforcement agency of the Australian Government responsible for investigating Crime in Australia, crime and protecting the national security of the Commonwealth ...

and the CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency that is responsible for scientific research and its commercial and industrial applications.

CSIRO works with leading organisations arou ...

during the war, and also created a number of new state-owned enterprises to aid the post-war economy. He made a significant impression on other world leaders at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference

Events

January

* January 1

** The Czechoslovak Legions occupy much of the self-proclaimed "free city" of Bratislava, Pressburg (later Bratislava), enforcing its incorporation into the new republic of Czechoslovakia.

** HMY Iolaire, HMY '' ...

, where he secured Australian control of the former German New Guinea

German New Guinea () consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups, and was part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , became a German protectorate in 188 ...

.

At the 1922 Australian federal election

The 1922 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 16 December 1922. All 75 seats in the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Australian Senate, Senate were up for election. The ...

, the Nationalists lost their majority in parliament and were forced to form a coalition

A coalition is formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political, military, or economic spaces.

Formation

According to ''A G ...

with the Country Party. Hughes's resignation was the price for Country Party support, and he was succeeded as prime minister by Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician, statesman and businessman who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929. He held office as ...

. He became one of Bruce's leading critics over time, and in 1928, following a dispute over industrial relations, he and his supporters crossed the floor on a confidence motion and brought down the government. After a period as an independent, Hughes formed his own organisation, the Australian Party

The Australian Party was a political party founded and led by former Australian prime minister Billy Hughes after his expulsion from the Nationalist Party. The party was formed in 1929, and at its peak had five members of federal parliament. ...

, which in 1931 merged into the new United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four Elections in Australia, federal elections in that time, usually governing Coalition (Australia), in coalition ...

(UAP). He returned to cabinet in 1934, and became known for his prescient warnings against Japanese imperialism. As late as 1939, he missed out on a second stint as prime minister by only a handful of votes, losing the 1939 United Australia Party leadership election

The United Australia Party held a leadership election on 18 April 1939, following the death in office of Prime Minister Joseph Lyons on 7 April. Robert Menzies narrowly defeated Billy Hughes – a former Nationalist prime minister – on the thir ...

to Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

.

Hughes is generally acknowledged as one of the most influential Australian politicians of the 20th century. He was a controversial figure throughout his lifetime, and his legacy continues to be debated by historians. His strong views and abrasive manner meant he frequently made political enemies, often from within his own parties. Hughes's opponents accused him of engaging in authoritarianism and populism, as well as inflaming sectarianism; his use of the ''War Precautions Act 1914

The War Precautions Act 1914 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which gave the Government of Australia special powers for the duration of World War I and for six months afterwards.

It was held by the High Court of Australia in '' Farey ...

'' was particularly controversial. His former colleagues in the Labor Party considered him a traitor, while conservatives were suspicious of what they viewed as his socialist economic policies. He was extremely popular among the general public, particularly ex-servicemen, who affectionately nicknamed him "the little digger".

Early years

Birth and family background

Hughes was born on 25 September 1862, at 7 Moreton Place,

Hughes was born on 25 September 1862, at 7 Moreton Place, Pimlico

Pimlico () is a district in Central London, in the City of Westminster, built as a southern extension to neighbouring Belgravia. It is known for its garden squares and distinctive Regency architecture. Pimlico is demarcated to the north by Lon ...

, London, the son of William Hughes and the former Jane Morris. His parents were both Welsh. His father, who worked as a carpenter and joiner at the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster is the meeting place of the Parliament of the United Kingdom and is located in London, England. It is commonly called the Houses of Parliament after the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two legislative ch ...

, was from North Wales and was a fluent Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

speaker. His mother, a domestic servant, was from the small village of Llansantffraid-ym-Mechain

Llansantffraid-ym-Mechain is a large village in the community (Wales), community of Llansantffraid, in Powys, Mid Wales. It is close to the border with Shropshire in England, about south-west of Oswestry and north of Welshpool. It is on the A4 ...

(near the English border), and spoke only English. Hughes was an only child

An only child is a person with no siblings, by birth or adoption.

Overview

Throughout history, only-children were relatively uncommon. From around the middle of the 20th century, birth rates and average family sizes fell sharply for a number of ...

; at the time of their marriage, in June 1861, his parents were both 37 years old.

Wales

Hughes's mother died in May 1869, when he was six years old. His father subsequently sent him to be raised by relatives in Wales. During the school term, he lived with his father's sister, Mary Hughes, who kept a boarding house inLlandudno

Llandudno (, ) is a seaside resort, town and community (Wales), community in Conwy County Borough, Wales, located on the Creuddyn peninsula, which protrudes into the Irish Sea. In the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 UK census, the community � ...

named "Bryn Rosa". He earned pocket money by doing chores for his aunt's tenants and singing in the choir at the local church. Hughes began his formal education in Llandudno, attending two small single-teacher schools. He spent his holidays with his mother's family in Llansantffraid. There, he divided his time between "Winllan", the farm of his widowed aunt (Margaret Mason), and "Plas Bedw", the neighbouring farm of his grandparents (Peter and Jane Morris).

Hughes regarded his early years in Wales as the happiest time of his life. He was immensely proud of his Welsh identity, and he later became active in the Welsh Australian

Welsh Australians () are citizens of Australia whose ancestry originates in Wales.

Demographics

According to the 2006 Australian census 25,317 Australian residents were born in Wales, while 113,242 (0.44%) claimed Welsh ancestry, either al ...

community, frequently speaking at Saint David's Day

Saint David's Day ( or ), or the Feast of Saint David, is the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on 1 March, the date of Saint David's death in 589 AD.

Traditional festivities include wearing daffodils and leeks, ...

celebrations. Hughes called Welsh the "language of heaven", but his own grasp of it was patchy. Like many of his contemporaries, he had no formal schooling in Welsh, and had particular difficulties with spelling. Nonetheless, he received and replied to correspondence from Welsh-speakers throughout his political career, and as prime minister famously traded insults in Welsh with David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

.

London

At the age of eleven, Hughes was enrolled in St Stephen's School,Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, one of the many church schools established by the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, 1st Baroness Burdett-Coutts

Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts, 1st Baroness Burdett-Coutts ( Burdett; 21 April 1814 – 30 December 1906) was a British philanthropist, the daughter of Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet and Sophia, formerly Coutts, daughter of banker Thomas ...

. He won prizes in geometry and French, receiving the latter from Lord Harrowby. After finishing his elementary schooling, he was apprenticed as a "pupil-teacher

Pupil teacher was a training program in wide use before the twentieth century, as an apprentice system for teachers. With the emergence in the beginning of the nineteenth century of education for the masses, demand for teachers increased. By 1840, ...

" for five years, instructing younger students for five hours a day in exchange for personal lessons from the headmaster and a small stipend. At St Stephen's, Hughes came into contact with the poet Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

, who was an examiner and inspector for the local school district. Arnold – who coincidentally had holidayed at Llandudno – took a liking to Hughes, and gifted him a copy of the Complete Works of Shakespeare

The ''Complete Works of William Shakespeare'' is the standard name given to any volume containing all the plays and poems of William Shakespeare. Some editions include several works that were not completely of Shakespeare's authorship (collabora ...

; Hughes credited Arnold with instilling his lifelong love of literature.

After finishing his initial apprenticeship, Hughes stayed on at St Stephen's as a teaching assistant. He had no interest in teaching as a career though, and also declined Matthew Arnold's offer to secure him a clerkship at

After finishing his initial apprenticeship, Hughes stayed on at St Stephen's as a teaching assistant. He had no interest in teaching as a career though, and also declined Matthew Arnold's offer to secure him a clerkship at Coutts

Coutts & Co. () is a British private bank and wealth manager headquartered in London, England.

Founded in 1692, it is the eighth oldest bank in the world. Today, Coutts forms part of NatWest Group's wealth management division. In the Channe ...

. His relative financial security allowed him to pursue his own interests for the first time, which included bellringing, boating on the Thames, and travel (such as a two-day trip to Paris). He also joined a volunteer battalion of the Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many war ...

, which consisted mainly of artisans and white-collar workers. In later life, Hughes recalled London as "a place of romance, mystery and suggestion".

First years in Australia

Queensland

At the age of 22, finding his prospects in London dim, Hughes decided to emigrate to Australia. Taking advantage of an assisted-passage scheme offered by theColony of Queensland

The Colony of Queensland was a colony of the British Empire from 1859 to 1901, when it became a State in the federal Australia, Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901. At its greatest extent, the colony included the present-day Queensland, ...

, he arrived in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

on 8 December 1884 after a two-month journey. On arrival, he gave his year of birth as 1864, a deception that was not uncovered until after his death. Hughes attempted to find work with the Education Department, but was either not offered a position or found the terms of employment to be unsuitable. He spent the next two years as an itinerant labourer, working various odd jobs. In his memoirs, Hughes claimed to have worked variously as a fruitpicker, tally clerk, navvy

Navvy, a Clipping (morphology), clipping of navigator (United Kingdom, UK) or navigational engineer (United States, US), is particularly applied to describe the manual Laborer, labourers working on major civil engineering projects and occasional ...

, blacksmith's striker

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

, station hand

In Australia and New Zealand, a station is a large landholding used for producing livestock, predominantly cattle or sheep, that needs an extensive range of grazing land. The owner of a station is called a pastoralist or a grazier, corres ...

, drover, and saddle

A saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals.

It is not know ...

r's assistant, and to have travelled (mostly on foot) as far north as Rockhampton

Rockhampton is a city in the Rockhampton Region of Central Queensland, Australia. In the , the population of Rockhampton was 79,293. A common nickname for Rockhampton is "Rocky", and the demonym of Rockhampton is Rockhamptonite.

The Scottish- ...

, as far west as Adavale

Adavale is a rural town and Suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Shire of Quilpie, Queensland, Australia. In the , the locality of Adavale had a population of 72 people.

Geography

Adavale is in South West Queensland, west of t ...

, and as far south as Orange, New South Wales

Orange is a city in the Central Tablelands region of New South Wales, Australia. It is west of the state capital, Sydney on a great circle at an altitude of . Orange had an urban population of 41,920 at the 2021 Australia Census, 2021 Cens ...

. He also claimed to have served briefly in both the Queensland Defence Force

Until Australia became a Federation in 1901, each of the six colonies was responsible for its own defence. From 1788 until 1870 this was done with British regular forces. In all, 24 British infantry regiments served in the Australian colonies. ...

and the Queensland Maritime Defence Force. Hughes's accounts are by their nature unverifiable, and his biographers have cast doubt on their veracity – Fitzhardinge states that they were embellished at best and at worst "a world of pure fantasy".

New South Wales

Hughes moved to

Hughes moved to Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

in about mid-1886, working his way there as a deckhand and galley cook aboard SS ''Maranoa''. He found occasional work as a line cook, but at one point supposedly had to resort to living in a cave on The Domain for a few days. Hughes eventually found a steady job at a forge, making hinges for colonial ovens. Around the same time, he entered into a common-law marriage

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, de facto marriage, more uxorio or marriage by habit and repute, is a marriage that results from the parties' agreement to consider themselves married, follo ...

with Elizabeth Cutts, his landlady's daughter; they had six children together. In 1890, Hughes moved to Balmain. The following year, with his wife's financial assistance, he was able to open a small shop selling general merchandise. The income from the shop was not enough to live on, so he also worked part-time as a locksmith and umbrella salesman, and his wife as a washerwoman. One of Hughes's acquaintances in Balmain was William Wilks, another future MP, while one of the customers at his shop was Frederick Jordan, a future Chief Justice of New South Wales

The Chief Justice of New South Wales is the senior judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Australian state of New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States a ...

.

Early political career

In Balmain, Hughes became aGeorgist

Georgism, in modern times also called Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that people should own the value that they produce themselves, while the economic rent derived from land—includ ...

, a street-corner speaker, president of the Balmain Single Tax League

The Single Tax League was a Georgist Australian political party that flourished throughout the 1920s and 1930s based on support for single tax.

Based upon the ideas of Henry George, who argued that all taxes should be abolished, save for a singl ...

, and joined the Australian Socialist League

The Socialist Labor Party was a socialist political party of Australia that existed from 1901 to the 1970s. Originally formed as the Australian Socialist League in 1887, it had members such as George Black, New South Wales Premier William Hol ...

. He was an organiser with the Australian Workers' Union

The Australian Workers' Union (AWU) is one of Australia's largest and oldest trade unions. It traces its origins to unions founded in the pastoralism, pastoral and mining industries in the late 1880s and it currently has approximately 80,000 ...

and may have already joined the newly formed Labor Party. In 1894, Hughes spent eight months in central New South Wales organising for the Amalgamated Shearers' Union of Australasia

The Amalgamated Shearers' Union of Australasia was an early Australian trade union. It was formed in January 1887 with the amalgamation of the Wagga Shearers Union and Bourke Shearers Union in New South Wales with the Victorian-based Australian S ...

and then won the Electoral district of Sydney-Lang

Sydney-Lang was an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales, created in 1894 from part of the electoral district of West Sydney in inner Sydney and named after Presbyterian clergyman, writer, pol ...

of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament House ...

by 105 votes.

While in Parliament he became secretary of the Wharf Labourer's Union. In 1900 he founded and became first national president of the Waterside Workers' Union. During this period Hughes studied law, and was admitted as a barrister in 1903. Unlike most Labor men, he was a strong supporter of Federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

and Georgism

Georgism, in modern times also called Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that people should own the value that they produce themselves, while the economic rent derived from land—includ ...

.

In 1901 Hughes was elected to the first federal Parliament as Labor MP for the

In 1901 Hughes was elected to the first federal Parliament as Labor MP for the Division of West Sydney

The Division of West Sydney was an Divisions of the Australian House of Representatives, Australian electoral division in the states and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales. It was located in the inner western suburbs of Sydney ...

. He opposed the Barton government's proposals for a small professional army and instead advocated compulsory universal training. In 1903, he was admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

after several years part-time study. He became a King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

(KC) in 1909.

In 1911, he married Mary Campbell. He was Minister for External Affairs in

In 1911, he married Mary Campbell. He was Minister for External Affairs in Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia from April to August 1904. He held office as the inaugural federal leader of the Au ...

's first Labor government. He was Attorney-General in Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian ...

's three Labor governments in 1908–09, 1910–13 and 1914–15.

In 1913, at the foundation ceremony of Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

as the capital of Australia, Hughes gave a speech proclaiming that the country was obtained via the elimination of the indigenous population. "We were destined to have our own way from the beginning.. nd.killed everybody else to get it," Hughes said, adding that "the first historic event in the history of the Commonwealth we are engaged in today swithout the slightest trace of that race we have banished from the face of the earth." But he warned that "we must not be too proud lest we should, too, in time disappear."

His abrasive manner (his chronic dyspepsia

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier ...

was thought to contribute to his volatile temperament) made his colleagues reluctant to have him as Leader. His on-going feud with King O'Malley

King O'Malley (2 July 1858 not confirmed – 20 December 1953) was an American-born Australian politician who served in the House of Representatives from 1901 to 1917, and served two terms as Minister for Home Affairs (1910–1913; 1915–16). ...

, a fellow Labor minister, was a prominent example of his combative style.

Hughes was also the club patron for the Glebe Rugby League team in the debut year of Rugby League in Australia, in 1908. Hughes was one of a number of prominent Labor politicians who were aligned with the Rugby League movement in Sydney in 1908. Rugby League was borne out of a player movement against the Metropolitan Rugby Union who refused to compensate players for downtime from their jobs due to injuries sustained playing Rugby Union. Labor politicians aligned themselves with the new code as it was seen as a strong social standpoint, politically, and it was an enthusiastic professional game, which made the politicians themselves appear in a similar vein, in their opinions anyway.

Prime minister

Following the

Following the 1914 Australian federal election

The 1914 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 5 September 1914. The election had been called before the declaration of war in August 1914. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and all 36 seats in the Senate were up for el ...

, the Labor Prime Minister of Australia, Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the fifth prime minister of Australia from 1908 to 1909, 1910 to 1913 and 1914 to 1915. He held office as the leader of the Australian ...

, found the strain of leadership during World War I taxing and faced increasing pressure from the ambitious Hughes who wanted Australia to be firmly recognised on the world stage. By 1915 Fisher's health was suffering and, in October, he resigned and was succeeded by Hughes. In social policy, Hughes introduced an institutional pension for pensioners in benevolent asylums, equal to the difference between the 'act of grace' payment to the institution and the rate of IP.

From March to June 1916, Hughes was in Britain, where he delivered a series of speeches calling for imperial co-operation and economic warfare against Germany. These were published under the title ''The Day—and After'', which was a bestseller. His biographer, Laurie Fitzhardinge, said these speeches were "electrifying" and that Hughes "swept his hearers off their feet". According to two contemporary writers, Hughes's speeches "have in particular evoked intense approbation, and have been followed by such a quickening power of the national spirit as perhaps no other orator since Chatham ever aroused".

In July 1916 Hughes was a member of the British delegation at the Paris Economic Conference

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, which met to decide what economic measures to take against Germany. This was the first time an Australian representative had attended an international conference.

Hughes was a strong supporter of Australia's participation in World War I and, after the loss of 28,000 men as casualties (killed, wounded and missing) in July and August 1916, Generals Birdwood and White of the First Australian Imperial Force

The First Australian Imperial Force (1st AIF) was the main Expeditionary warfare, expeditionary force of the Australian Army during the First World War. It was formed as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) following United Kingdom of Great Bri ...

(AIF) persuaded Hughes that conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

was necessary if Australia was to sustain its contribution to the war effort.

However, a two-thirds majority of his party, which included Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

and trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

representatives as well as the Industrialists (Socialists) such as Frank Anstey

Francis George Anstey (18 August 186531 October 1940) was an Australian politician and writer. He served as a member of the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives from 1910 to 1934, representing the Australian Labor Party ...

, were bitterly opposed to this, especially in the wake of what was regarded by many Irish Australians (most of whom were Roman Catholics) as Britain's excessive response to the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

of 1916.

In October, Hughes held a national plebiscite for conscription, but it was narrowly defeated. The enabling legislation was the ''Military Service Referendum Act 1916'' and the outcome was advisory only. The narrow defeat (1,087,557 Yes and 1,160,033 No), however, did not deter Hughes, who continued to argue vigorously in favour of conscription. This revealed the deep and bitter split within the Australian community that had existed since before Federation, as well as within the members of his own party.

Conscription had been in place since the 1910 Defence Act, but only in the defence of the nation. Hughes was seeking via a referendum to change the wording in the act to include "overseas". A referendum was not necessary but Hughes felt that in light of the seriousness of the situation, a vote of "Yes" from the people would give him a mandate to bypass the Senate. The Lloyd George Government of Britain did favour Hughes but only came to power in early December 1916, over a month after the first referendum. The predecessor Asquith government greatly disliked Hughes considering him to be "a guest, rather than the representative of Australia". According to David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

: "He and Asquith did not get on too well. They would not. They were antipathetic types. As Hughes was never over-anxious to conceal his feelings or restrain his expression of them, and was moreover equipped with a biting tongue, the consultations between them were not agreeable to either".

In reaction to Hughes's campaign for conscription, on 15 September 1916 the NSW executive of the Political Labour League (the state Labor Party organisation at the time) expelled him and other leading New South Wales pro-conscription advocates from the Labor movement. Hughes remained as leader of the federal parliamentary Labor Party until, at 14 November caucus meeting, a no-confidence motion against him was passed. Hughes and 24 others, including almost all of the Parliamentary talent, walked out to form a new party heeding Hughes's cry "Let those who think like me, follow me." This left behind the 43 members of the Industrialists and Unionists factions. That same evening Hughes tendered his resignation to the Governor-General, received a commission to form a new Government, and had his recommendations accepted. Years later, Hughes said, "I did not leave the Labor Party, The party left me." The timing of Hughes's expulsion from the Labor Party meant that he became the first Labor leader who never led the party to an election. On 15 November, Frank Tudor

Francis Gwynne Tudor (29 January 1866 – 10 January 1922) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy ...

was elected unopposed as the new leader of the Federal Parliamentary Australian Labor Party.

Nationalist Party

Hughes and his followers, which included many of Labor's early leaders, called themselves theNational Labor Party

The National Labor Party (NLP) was an Australian political party formed by Prime Minister Billy Hughes in November 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of ...

and began laying the groundwork for forming a party that they felt would be both avowedly nationalist as well as socially radical. Hughes was forced to conclude a confidence and supply

In parliamentary system, parliamentary democracies based on the Westminster system, confidence and supply is an arrangement under which a minority government (one which does not control a majority in the legislature) receives the support of one ...

agreement with the opposition Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

to stay in office.

A few months later, the Governor-General, Ronald Munro Ferguson, 1st Viscount Novar

Ronald Craufurd Munro Ferguson, 1st Viscount Novar, (6 March 1860 – 30 March 1934) was a British politician who served as the sixth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1914 to 1920.

Munro Ferguson was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Sc ...

, persuaded Hughes and Liberal Party leader Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook (7 December 1860 – 30 July 1947) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the sixth Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1913 to 1914. He held office as the leader of the Fusion L ...

(himself a former Labor man) to turn their wartime coalition into a formal party. This was the Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party, also known as the National Party, was an Australian political party. It was formed in February 1917 from a merger between the Commonwealth Liberal Party, Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the latter formed by ...

, which was formally launched in February. Although the Liberals were the larger partner in the merger, Hughes emerged as the new party's leader, with Cook as his deputy. The presence of several working-class figures—including Hughes—in what was basically an upper- and middle-class party allowed the Nationalists to convey an image of national unity. At the same time, he became and remains a traitor in Labor histories.

At the 1917 Australian federal election

Events

Below, the events of World War I have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 9 – WWI – Battle of Rafa: The last substantial Ottoman Army garrison on the Sinai Peninsula is captured by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's ...

Hughes and the Nationalists won a huge electoral victory, which was magnified by the large number of Labor MPs who followed him out of the party. At this election Hughes gave up his working-class Sydney seat and was elected for the Division of Bendigo

The Division of Bendigo is an Divisions of the Australian House of Representatives, Australian electoral division in the states and territories of Australia, state of Victoria (Australia), Victoria. The division was proclaimed in 1900, and was ...

, after he won the seat by defeating the sitting Labor MP Alfred Hampson, and both marks the only time that a sitting prime minister had challenged and ousted another sitting MP for his seat along with him becoming the first of only a handful of Members of the Australian Parliament who have represented more than one state or territory

This is a list of Members of the Parliament of Australia who represented more than one state or territory during their federal parliamentary career.

Most people in the list represented different states or territories in the House of Representat ...

.

Hughes had promised to resign if his Government did not win the power to conscript. Queensland Premier T. J. Ryan

Thomas Joseph Ryan (1 July 1876 – 1 August 1921) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of Queensland from 1915 to 1919, as leader of the state Labor Party. He resigned to enter federal politics, sitting in the House of Represen ...

was a key opponent to conscription, and violence almost broke out when Hughes ordered a raid on the Government Printing Office

In November 1917 during World War I, the Australian Government conducted a raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office in Brisbane. The aim of the raid was to confiscate any copies of the Hansard, the official parliamentary transcript, whi ...

in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

, with the aim of confiscating copies of Hansard

''Hansard'' is the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official printe ...

that covered debates in the Queensland Parliament

The Parliament of Queensland is the unicameral legislative body of the Australian state of Queensland. As provided under the Constitution of Queensland, the Parliament consists of the King, represented by the Governor of Queensland, and the ...

where anti-conscription sentiments had been aired. A second plebiscite on conscription was held in December 1917, but was again defeated, this time by a wider margin. Hughes, after receiving a vote of confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fit ...

in his leadership by his party, resigned as prime minister. However, there were no credible alternative candidates. For this reason, Munro-Ferguson used his reserve power

In a parliamentary or semi-presidential system of government, a reserve power, also known as discretionary power, is a power that may be exercised by the head of state (or their representative) without the approval of another branch or part of th ...

to immediately re-commission Hughes, thus allowing him to remain as prime minister while keeping his promise to resign.

Domestic policy

Electoral reform

The government replaced thefirst-past-the-post

First-past-the-post (FPTP)—also called choose-one, first-preference plurality (FPP), or simply plurality—is a single-winner voting rule. Voters mark one candidate as their favorite, or First-preference votes, first-preference, and the cand ...

electoral system applying to both houses of the Federal Parliament under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1903 with a preferential system for the House of Representatives in 1918. That preferential system has essentially applied ever since. A multiple majority-preferential system was introduced at the 1919 Australian federal election

The 1919 Australian federal election was held on 13 December 1919 to elect members to the Parliament of Australia. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist ...

for the Senate, and that remained in force until it was changed to a quota-preferential system of proportional representation in 1948. Those changes were considered to be a response to the emergence of the Country Party, so that the non-Labor vote would not be split, as it would have been under the previous first-past-the-post system.

Science and industry

=Research body

= In early 1916, Hughes established the Advisory Council on Science and Industry, the first national body for scientific research and the first iteration of what is now theCommonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency that is responsible for scientific research and its commercial and industrial applications.

CSIRO works with leading organisations arou ...

(CSIRO). The council had no basis in legislation, and was intended only as a temporary body to be replaced with "Bureau of Science and Industry" as soon as possible. However, due to wartime stresses and other considerations the council endured until 1920, at which point an act of parliament was passed transforming it into a new government agency, the Institute of Science and Industry. According to Fitzhardinge: "The whole affair was highly typical of Hughes's methods. An idea coming from outside happened to chime with his preoccupation of the moment. He seized it, put his own stamp on it, and pushed it through to the point of realization. Then, having established the machinery, he expected it to run itself while he turned his full energies elsewhere, and tended to be evasive or testy if he was called back to it. Yet his interest was genuine, and without his enthusiasm and drive the Commonwealth intervention would either not have come at all or would have been far slower".

=Aviation

= It was a scheme of Hughes' devising that set the scene for long-distance civil aviation in Australia. His interest in the possibilities of peacetime aviation was sparked by his flights travelling between London and Paris for the Paris Peace Conference. On a Christmas visit the year before, in 1918, to wounded servicemen convalescing in Kent, Hughes had met Australian pilots who were facing the seven-week sea voyage home and were eager to pioneer an air route and fly to Australia instead. Such a vast distance had never been attempted by air; the first ocean crossing by aircraft occurred only months later in June 1919. Despite the risks of such a venture, Hughes' eagerness to see Australia at the forefront of technological development and in a central position in world affairs, had him seeking the support of his cabinet for a scheme to establish a Britain–Australia route. A February 1919 cable from Hughes said: "Several Australian aviators are desirous of attempting flight London to Australia they are all first-class men and very keen your thoughts", and also advised the cabinet of the advantages that such a groundbreaking flight would offer Australia: "would be a great advertisement for Australia and would concentrate the eyes of the world on us." A month later, the acting prime minister of Australia, William Watt, announced: "With a view to stimulating aerial activity, the Commonwealth Government has decided to offer £10,000 for the first successful flight to Australia from Great Britain." The reward would go to the first crew to complete the journey in under thirty days. BrothersRoss Ross may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Ross (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name Ross, as well as the meaning

* Clan Ross, a Highland Scottish clan

Places Antarctica

* Ross Sea

...

and Keith Smith, pilot and navigator, and mechanics Walter Shiers and Jim Bennett won the prize when their Vickers Vimy

The Vickers Vimy was a British heavy bomber aircraft developed and manufactured by Vickers Limited. Developed during the latter stages of the First World War to equip the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), the Vimy was designed by Rex Pierson, Vickers ...

G-EAOU twin engine plane landed in Darwin on 10 December 1919. The flight set a record for distance travelled by aircraft, having flown , surpassing the previous record of set the year before on a Cairo to Delhi flight. Hughes achieved his aim of garnering world press attention for Australia, while Australia's first, and one of the world's earliest airlines, Qantas

Qantas ( ), formally Qantas Airways Limited, is the flag carrier of Australia, and the largest airline by fleet size, international flights, and international destinations in Australia and List of largest airlines in Oceania, Oceania. A foundi ...

, was founded in 1920, commencing international passenger flights in 1935. A cofounder of the airline, Hudson Fysh

Sir Wilmot Hudson Fysh (7 January 18956 April 1974) was an Australian aviator and businessman. A founder of the Australian airline company Qantas, Fysh was born in Launceston, Tasmania. Serving in the Battle of Gallipoli and Palestine Camp ...

, who had been commissioned by the government to survey landing fields in northern Australia for the competition, was present to greet the crew of the Vimy when it landed.

Paris Peace Conference

In 1919 Hughes, with former prime minister

In 1919 Hughes, with former prime minister Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook (7 December 1860 – 30 July 1947) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the sixth Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1913 to 1914. He held office as the leader of the Fusion L ...

, travelled to Paris to attend the Versailles Peace Conference

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines Department of Île-de-France region in France.

The palace is owned by the government of F ...

. He remained away for 16 months, and signed the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

on behalf of Australia – the first time Australia had signed an international treaty.

At a meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet

The Imperial War Cabinet (IWC) was the British Empire's wartime coordinating body. It met over three sessions, the first from 20 March to 2 May 1917, the second from 11 June to late July 1918, and the third from 20 or 25 November 1918 to early Ja ...

on 30 December 1918, Hughes warned that if they "were not very careful, we should find ourselves dragged quite unnecessarily behind the wheels of President Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's chariot". He added that it was intolerable for Wilson "to dictate to us how the world was to be governed. If the saving of civilisation had depended on the United States, it would have been in tears and chains to-day". He also said that Wilson had no practical scheme for a League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and added: "The League of Nations was to him what a toy was to a child—he would not be happy till he got it". At the Paris Peace Conference, Hughes clashed with Wilson. When Wilson reminded him that he spoke for only a few million people, Hughes replied: "I speak for 60,000 dead. How many do you speak for?"

The British Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s of New Zealand, South Africa and Australia argued their case to keep their occupied German possessions of German Samoa, German South West Africa, and German New Guinea respectively; these territories were given as " Class C Mandates" to the respective Dominions. In a same-same deal Japan obtained control over its occupied German possessions north of the equator. At the meeting of 30 January, Hughes clashed with Wilson on the question of mandates, as Hughes preferred formal sovereignty over the islands. According to the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, Wilson was dictatorial and arrogant in his approach to Hughes, adding that "Hughes was the last man I would have chosen to handle in that way". Lloyd George described how, after Hughes stated his case against subjecting the islands conquered by Australia to a mandate:

President Wilson pulled him up sharply and proceeded to address him personally in what I would describe as a heated allocution rather than an appeal. He dwelt on the seriousness of defying world opinion on this subject. Mr. Hughes, who listened intently, with his hand cupped around his ear so as not to miss a word, indicated at the end that he was still of the same opinion. Whereupon the President asked him slowly and solemnly: "Mr. Hughes, am I to understand that if the whole civilised world asks Australia to agree to a mandate in respect of these islands, Australia is prepared still to defy the appeal of the whole civilised world?” Mr. Hughes answered: "That's about the size of it, President Wilson". Mr. Massey grunted his assent of this abrupt defiance.However, South Africa's

Louis Botha

Louis Botha ( , ; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first Prime Minister of South Africa, prime minister of the Union of South Africa, the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war v ...

intervened on Wilson's side, and the mandates scheme went through. Hughes's frequent clashes with Wilson led to Wilson labelling him a "pestiferous varmint".

Hughes, unlike Wilson or South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

, demanded heavy reparations from the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, suggesting the sum of £24,000,000,000 of which Australia would claim many millions to off-set its own war debt. Hughes was a member of the British delegation on the Reparations Committee, with Walter Cunliffe, 1st Baron Cunliffe

Walter Cunliffe, 1st Baron Cunliffe (3 December 1855 – 6 January 1920) was a British banker who established the merchant banking business of Cunliffe Brothers (after 1920, Goschens & Cunliffe) in London, and who was Governor of the Bank of Eng ...

and John Hamilton, 1st Viscount Sumner

John Andrew Hamilton, 1st Viscount Sumner, (3 February 1859 – 24 May 1934) was a British lawyer and judge. He was appointed a judge of the High Court of Justice (King's Bench Division) in 1909, a Lord Justice of Appeal in 1912 and a Lord of ...

. When the Imperial Cabinet met to discuss the Hughes Report, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

asked Hughes if he had considered the effects that reparations would have on working-class German households. Hughes replied that "the Committee had been more concerned in considering the effects upon the working-class households in Great Britain, or in Australia, if the Germans did not pay an indemnity".

At the Treaty negotiations, Hughes was the most prominent opponent of the inclusion of Japan's Racial Equality Proposal

The Racial Equality Proposal was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was attached to it anyway, whic ...

, which as a result of lobbying by him and others was not included in the final Treaty. His position on this issue reflected the racist attitudes dominant among white Australians; informing David Lloyd George that he would leave the conference if the clause was adopted, Hughes clarified his opposition by announcing at a meeting that "ninety-five out of one hundred Australians rejected the very idea of equality." Hughes offered to accept the clause so long as it did not affect immigration policy but the Japanese turned the offer down. Lloyd George said that the clause "was aimed at the restrictions and disabilities which were imposed by certain states against Japanese emigration and Japanese settlers already within their borders".

Hughes had entered politics as a trade unionist, and like most of the Australian working class was very strongly opposed to Asian immigration to Australia (excluding Asian immigration was a popular cause with unions in Canada, the U.S., Australia and New Zealand in the early 20th century). Hughes believed that accepting the Racial Equality Clause would mean the end of the White Australia policy that had been adopted in 1901, one of his subordinates writing: "No Gov't could live for a day in Australia if it tampered with a White Australia ...The position is this – either the Japanese proposal means something or it means nothing: if the former, out with it; if the latter, why have it?"{ He later said that "the right of the state to determine the conditions under which persons shall enter its territories cannot be impaired without reducing it to a vassal state", adding: "When I offered to accept it provided that words were incorporated making it clear that it was not to be used for the purpose of immigration or of impairing our rights of self-government in any way, he Japanese delegate Baron Makino was unable to agree".

When the proposal failed, Hughes reported in the Australian parliament:The White Australia is yours. You may do with it what you please, but at any rate, the soldiers have achieved the victory and my colleagues and I have brought that great principle back to you from the conference, as safe as it was on the day when it was first adopted.Japan was notably offended by Hughes's position on the issue. Like

Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

of South Africa, Hughes was concerned by the rise of Japan. Within months of the declaration of the European War in 1914, Japan, Australia and New Zealand had seized all German territorial possessions in the Pacific. Though Japan had occupied German possessions with the blessing of the British, Hughes felt alarm at this turn of events.Lowe, "Australia in the World", p. 129.

With reference to Hughes's actions at the Peace Conference, the historian Ernest Scott

Sir Ernest Scott (21 June 1867 – 6 December 1939) was an Australian historian and professor of history at the University of Melbourne from 1913 to 1936.

Early life

Scott was born in Northampton, England, on 21 June 1867, the son of Hannah ...

said that although Hughes failed to secure sovereignty over the conquered German islands or relief for Australia's war debts, "both he and his countrymen found satisfaction with his achievements. By characteristic methods he had gained single-handed at least the points that were vital to his nation's existence". Joan Beaumont

Joan Errington Beaumont, (born 25 October 1948) is an Australian historian and academic, who specialises in foreign policy and the Australian experience of war. She is professor emerita in the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the Austral ...

said Hughes became "something of a folk hero in later Australian historiography for his assertiveness at the Paris peace conference".

Seth Tillman described him as "a noisesome demagogue", the " bete noir of Anglo-American relations". Unlike Smuts, Hughes opposed the concept of the League of Nations, as in it he saw the flawed idealism of "collective security". He declared in June 1919 that Australia would rely on the League "but we shall keep our powder dry".

On returning home from the conference, he was greeted with a welcome "unsurpassed in the history of Australia" which historian Ann Moyal

Ann Veronica Helen Moyal (née Hurley, formerly Cousins and Mozley; 23 February 1926 – 21 July 2019) was an Australian historian known for her work in the history of science. She held academic positions at the Australian National University (A ...

says was the highpoint of his career.

1920–1923

Hughes demanded that Australia have independent representation within the newly-formedLeague of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. Despite the rejection of his conscription policy, Hughes retained popularity with Australian voters and, at the 1919 Australian federal election

The 1919 Australian federal election was held on 13 December 1919 to elect members to the Parliament of Australia. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Nationalist ...

, his government was comfortably re-elected.

After 1920, Hughes's political position declined. Many of the more conservative elements of his own party never trusted him because they thought he was still a socialist at heart, citing his interest in retaining government ownership of the Commonwealth Shipping Line and the Australian Wireless Company. However, they continued to support him for some time after the war, if only to keep Labor out of power.

A new party, the Country Party (known since 1975 as the National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia, commonly known as the Nationals or simply the Nats, is a Centre-right politics, centre-right and Agrarianism, agrarian List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia. Traditionally represe ...

, was formed, representing farmers who were discontented with the Nationalists' rural policies, in particular Hughes's acceptance of a much higher level of tariff protection for Australian industries, that had expanded during the war, and his support for price controls

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of go ...

on rural produce. In the New Year's Day Honours of 1922, Hughes's wife Mary was appointed a Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

(GBE).

At the 1921 Imperial Conference

The 1921 Imperial Conference met in London from 20 June to 5 August 1921. It was chaired by British prime minister David Lloyd George.

The Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominions met at the 1921 Imperial Conference to determine a ...

, Hughes argued unsuccessfully in favour of renewing the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The was an alliance between the United Kingdom and the Empire of Japan which was effective from 1902 to 1923. The treaty creating the alliance was signed at Lansdowne House in London on 30 January 1902 by British foreign secretary Lord Lans ...

.

At the 1922 Australian federal election

The 1922 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 16 December 1922. All 75 seats in the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Australian Senate, Senate were up for election. The ...

, Hughes gave up the seat of Bendigo and transferred to the upper-middle-class Division of North Sydney

The Division of North Sydney was an Australian Electoral Divisions, Australian electoral division in the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales from 1901 to 2025.

On 12 September 2024, the Australian Electoral Commissio ...

, thus giving up one of the last symbolic links to his working-class roots. The Nationalists lost their outright majority at the election. The Country Party, despite its opposition to Hughes's farm policy, was the Nationalists' only realistic coalition partner. However, party leader Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page (8 August 188020 December 1961) was an Australian politician and surgeon who served as the 11th prime minister of Australia from 7 to 26 April 1939, in a caretaker capacity following the death of Joseph Lyons. ...

let it be known that he and his party would not serve under Hughes. Under pressure from his party's right wing, Hughes resigned in February 1923 and was succeeded by his Treasurer, Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician, statesman and businessman who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929. He held office as ...

. His eight-year tenure was the longest for a prime minister until Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

passed him in 1957.

Whilst the incumbent prime minister, Hughes switched seats at both the 1917 and 1922 elections, the only prime minister to have done so not once but twice. All other elections have seen the prime minister re-contest the seat that they held prior to the election.

Political eclipse and re-emergence

Hughes played little part in parliament for the remainder of 1923. He rented a house inKirribilli, New South Wales

Kirribilli is a Suburb (Australia), suburb of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. One of the city's most established and affluent neighbourhoods, it is located three kilometres north of the Sydney central business district, in the Local governm ...

in his new electorate and was recruited by ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' to write a series of articles on topics of his choosing. In the articles he defended his legacy as prime minister and stated he would support the new government as long as it followed his principles. In 1924, Hughes embarked on a lecture tour of the United States. His health broke down midway through the tour, while he was in New York. As a result he cancelled the rest of his engagements and drove back across the country in a new Flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

automobile, which he brought back to Australia. Later in the year he purchased a house in Lindfield, which was to be his primary residence for the rest of his life. In 1925 Hughes again had little involvement in parliamentary affairs, but began to portray himself as "champion of Australian industries struggling to get established against foreign competition and government indifference", with the aid of his friends James Hume Cook and Ambrose Pratt

Ambrose Goddard Hesketh Pratt (31 August 1874 – 13 April 1944) was an Australian writer born into a cultivated family in Forbes, New South Wales.''Oxford Companion to Australian Literature'' (2nd ed.) Oxford University Press, Melbourne 1994

...

.

Hughes was furious at being ousted by his own party and nursed his grievance on the back-benches until 1929, when he led a group of back-bench rebels who crossed the floor

In some parliamentary systems (e.g., in Canada and the United Kingdom), politicians are said to cross the floor if they formally change their political affiliation to a political party different from the one they were initially elected under. I ...

of the Parliament to bring down the Bruce government. Hughes was expelled from the Nationalist Party, and formed his own party, the Australian Party

The Australian Party was a political party founded and led by former Australian prime minister Billy Hughes after his expulsion from the Nationalist Party. The party was formed in 1929, and at its peak had five members of federal parliament. ...

. After the Nationalists were heavily defeated in the ensuing election, Hughes initially supported the Labor government of James Scullin

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the ninth prime minister of Australia from 1929 to 1932. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

. He had a falling-out with Scullin over financial matters, however. In 1931 he buried the hatchet with his former non-Labor colleagues and joined the Nationalists and several right-wing Labor dissidents under Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Australia, from 1932 until his death in 1939. He held office as the inaugural leader of the United Australia Par ...

in forming the United Australia Party (UAP), under Lyons' leadership. He voted with the rest of the UAP to bring the Scullin government down.

1930s