Bertillon System on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

In 1716

In 1716

In 1883, Frenchman

In 1883, Frenchman  The system was soon adapted to police methods: it prevented impersonation and could demonstrate wrongdoing.

Bertillonage was before long represented in Paris by a collection of some 100,000 cards and became popular in several other countries' justice systems. England followed suit when in 1894, a committee sent to Paris to investigate the methods and its results reported favorably on the use of measurements for primary classification and recommended also the partial adoption of the system of finger prints suggested by

The system was soon adapted to police methods: it prevented impersonation and could demonstrate wrongdoing.

Bertillonage was before long represented in Paris by a collection of some 100,000 cards and became popular in several other countries' justice systems. England followed suit when in 1894, a committee sent to Paris to investigate the methods and its results reported favorably on the use of measurements for primary classification and recommended also the partial adoption of the system of finger prints suggested by

Phylogeography is the science of identifying and tracking major human migrations, especially in prehistoric times. Linguistics can follow the movement of languages and archaeology can follow the movement of artefact styles but neither can tell whether a culture's spread was due to a source population's physically migrating or to a destination population's simply copying the technology and learning the language. Anthropometry was used extensively by anthropologists studying human and racial origins: some attempted racial differentiation and

Phylogeography is the science of identifying and tracking major human migrations, especially in prehistoric times. Linguistics can follow the movement of languages and archaeology can follow the movement of artefact styles but neither can tell whether a culture's spread was due to a source population's physically migrating or to a destination population's simply copying the technology and learning the language. Anthropometry was used extensively by anthropologists studying human and racial origins: some attempted racial differentiation and

ArchaeologyInfo-003

. This school of physical anthropology generally went into decline during the 1940s.

In ''Crania Americana'' Morton claimed that Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Indians were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches. In 1873

In ''Crania Americana'' Morton claimed that Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Indians were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches. In 1873

Ariani, indogermani, stirpi mediterranee: aspetti del dibattito sulle razze europee (1870-1914)

, '' Cromohs'', 1998 Virchow later rejected measure of skulls as legitimate means of

Observable craniofacial differences included: head shape (mesocephalic, brachycephalic, dolichocephalic) breadth of nasal aperture, nasal root height, sagittal crest appearance, jaw thickness, brow ridge size and forehead slope. Using this skull-based categorization, German philosopher Christoph Meiners in his The Outline of History of Mankind (1785) identified three racial groups:

*

Observable craniofacial differences included: head shape (mesocephalic, brachycephalic, dolichocephalic) breadth of nasal aperture, nasal root height, sagittal crest appearance, jaw thickness, brow ridge size and forehead slope. Using this skull-based categorization, German philosopher Christoph Meiners in his The Outline of History of Mankind (1785) identified three racial groups:

*

Forensic Misclassification of Ancient Nubian Crania: Implications for Assumptions about Human Variation, Frank L'Engle Williams, Robert L. Belcher, and George J. Armelagos

(pdf)

Anthropometric Survey of Army Personnel: Methods and Summary Statistics 1988

* ISO 7250: Basic human body measurements for technological design,

Anthropometry Procedures Manual

'. CDC: Atlanta, USA; 2007. * *Folia Anthropologica: tudományos és módszertani folyóirat. 9: 5–17. ISSN 1786-5654 * (A classic review of human body sizes.) * Stewart A. "Kinanthropometry and body composition: A natural home for three dimensional photonic scanning". ''Journal of Sports Sciences'', March 2010; 28(5): 455–457. {{Historical definitions of race *

anthropometry

Anthropometry (, ) refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of biological anthropology, physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthr ...

includes its use as an early tool of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, use for identification, use for the purposes of understanding human physical variation in paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinsh ...

and in various attempts to correlate physical with racial and psychological traits. At various points in history, certain anthropometrics have been cited by advocates of discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

and eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

often as a part of some social movement

A social movement is either a loosely or carefully organized effort by a large group of people to achieve a particular goal, typically a Social issue, social or Political movement, political one. This may be to carry out a social change, or to re ...

or through pseudoscientific claims.

Craniometry and paleoanthropology

In 1716

In 1716 Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton

Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton (; 29 May 1716 – 1 January 1800) was a French natural history, naturalist and contributor to the ''Encyclopédie, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers''.

Biography

Daubent ...

, who wrote many essays on comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

for the Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

, published his ''Memoir on the Different Positions of the Occipital Foramen

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lobes of the cere ...

in Man and Animals'' (''Mémoire sur les différences de la situation du grand trou occipital dans l'homme et dans les animaux''). Six years later Pieter Camper (1722–1789), distinguished both as an artist and as an anatomist, published some lectures that laid the foundation of much work. Camper invented the " facial angle," a measure meant to determine intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

among various species. According to this technique, a "facial angle" was formed by drawing two lines: one horizontally from the nostril

A nostril (or naris , : nares ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbinates ...

to the ear

In vertebrates, an ear is the organ that enables hearing and (in mammals) body balance using the vestibular system. In humans, the ear is described as having three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear co ...

; and the other perpendicularly from the advancing part of the upper jawbone to the most prominent part of the forehead

In human anatomy, the forehead is an area of the head bounded by three features, two of the skull and one of the scalp. The top of the forehead is marked by the hairline, the edge of the area where hair on the scalp grows. The bottom of the fo ...

. Camper's measurements of facial angle were first made to compare the skulls of men with those of other animals. Camper claimed that antique statues presented an angle of 90°, Europeans of 80°, Central Africans of 70° and the orangutan of 58°.

Swedish professor of anatomy Anders Retzius (1796–1860) first used the cephalic index

The cephalic index or cranial index is a number obtained by taking the maximum width (biparietal diameter or BPD, side to side) of the head of an organism, multiplying it by 100 and then dividing it by their maximum length (occipitofrontal diame ...

in physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a natural science discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from ...

to classify ancient human remains found in Europe. He classed skulls in three main categories; "dolichocephalic" (from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

''kephalê'' "head", and ''dolikhos'' "long and thin"), "brachycephalic" (short and broad) and "mesocephalic" (intermediate length and width). Scientific research was continued by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (; 15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theorie ...

(1772–1844) and Paul Broca

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involve ...

(1824–1880), founder of the Anthropological Society in France in 1859. Paleoanthropologists still rely upon craniofacial anthropometry to identify species in the study of fossilized hominid bones. Specimens of ''Homo erectus'' and athletic specimens of ''Homo sapiens'', for example, are virtually identical from the neck down but their skulls can easily be told apart.

Samuel George Morton

Samuel George Morton (January 26, 1799 – May 15, 1851) was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer. As one of the early figures of scientific racism, he argued against monogenism, the single creation story of the Bible, instead sup ...

(1799–1851), whose two major monographs were the ''Crania Americana'' (1839), ''An Inquiry into the Distinctive Characteristics of the Aboriginal Race of America'' and ''Crania Aegyptiaca'' (1844) concluded that the ancient Egyptians

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower ...

were not Negroid but Caucasoid and that Caucasians and Negroes were already distinct three thousand years ago. Since ''The Bible'' indicated that Noah's Ark had washed up on Mount Ararat

Mount Ararat, also known as Masis or Mount Ağrı, is a snow-capped and dormant compound volcano in Eastern Turkey, easternmost Turkey. It consists of two major volcanic cones: Greater Ararat and Little Ararat. Greater Ararat is the highest p ...

only a thousand years before this Noah's sons could not account for every race on earth. According to Morton's theory of polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that humans are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views find little merit ...

the races had been separate from the start.David Hurst Thomas

David Hurst Thomas (born 1945) is the curator of North American Archaeology in the Division of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History and a professor at Richard Gilder Graduate School. He was previously a chairman of the American Mu ...

, ''Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity'', 2001, pp. 38–41 Josiah C. Nott and George Gliddon

George Robbins Gliddon (1809 – November 16, 1857) was an English-born American Egyptologist. He worked as a United States vice-consul in Egypt and assisted Muhammad Ali Pasha's plans to modernize Egypt by attaining sugar, rice, and other mills ...

carried Morton's ideas further. Charles Darwin, who thought the single-origin hypothesis essential to evolutionary theory

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certai ...

, opposed Nott and Gliddon in his 1871 ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English natural history, naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, ...

'', arguing for monogenism

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all humans. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assum ...

.

In 1856, workers found in a limestone quarry the skull of a Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

hominid male, thinking it to be the remains of a bear. They gave the material to amateur naturalist Johann Karl Fuhlrott who turned the fossils over to anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen. The discovery was jointly announced in 1857, giving rise to the discipline of paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinsh ...

. By comparing skeletons of apes to man, T. H. Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

(1825–1895) backed up Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certai ...

, first expressed in ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' (1859). He also developed the " Pithecometra principle," which stated that man and ape were descended from a common ancestor.

Eugène Dubois

Marie Eugène François Thomas Dubois (; 28January 185816December 1940) was a Dutch paleoanthropologist and geologist. He earned worldwide fame for his discovery of ''Pithecanthropus erectus'' (later redesignated ''Homo erectus''), or " Java Man" ...

' (1858–1940) discovery in 1891 in Indonesia of the "Java Man

Java Man (''Homo erectus erectus'', formerly also ''Anthropopithecus erectus or'' ''Pithecanthropus erectus'') is an early human fossil discovered in 1891 and 1892 on the island of Java (Indonesia). Estimated to be between 700,000 and 1,490,00 ...

", the first specimen of Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' ( ) is an extinction, extinct species of Homo, archaic human from the Pleistocene, spanning nearly 2 million years. It is the first human species to evolve a humanlike body plan and human gait, gait, to early expansions of h ...

to be discovered, demonstrated mankind's deep ancestry outside Europe. Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

(1834–1919) became famous for his "recapitulation theory

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an ...

", according to which each individual mirrors the evolution of the whole species during his life.

Typology and personality

Intelligence testing

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. Originally, IQ was a score obtained by dividing a person's mental age score, obtained by administering ...

was compared with anthropometrics. Samuel George Morton

Samuel George Morton (January 26, 1799 – May 15, 1851) was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer. As one of the early figures of scientific racism, he argued against monogenism, the single creation story of the Bible, instead sup ...

(1799–1851) collected hundreds of human skulls from all over the world and started trying to find a way to classify them according to some logical criterion. Morton claimed that he could judge intellectual capacity by cranial capacity

The size of the brain is a frequent topic of study within the fields of anatomy, biological anthropology, animal science and evolution. Measuring brain size and cranial capacity is relevant both to humans and other animals, and can be done by wei ...

. A large skull meant a large brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

and high intellectual capacity; a small skull indicated a small brain and decreased intellectual capacity. Modern science has since confirmed that there is a correlation between cranium size (measured in various ways) and intelligence as measured by IQ tests, although it is a weak correlation at about 0.2. Today, brain volume as measured with MRI scanners also find a correlation between brain size and intelligence at about 0.4.

Craniometry

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium (the main part of the skull), usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is d ...

was also used in phrenology

Phrenology is a pseudoscience that involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits. It is based on the concept that the Human brain, brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific ...

, which purported to determine character, personality traits, and criminality on the basis of the shape of the head. At the turn of the 19th century, Franz Joseph Gall

Franz Joseph Gall or Franz Josef Gall (; 9 March 175822 August 1828) was a German neuroanatomist, physiology, physiologist, and pioneer in the study of the localization of mental functions in the brain.

Claimed as the founder of the pseudoscienc ...

(1758–1822) developed "cranioscopy" (Ancient Greek ''kranion'' "skull", ''scopos'' "vision"), a method to determine the personality and development of mental and moral faculties on the basis of the external shape of the skull. Cranioscopy was later renamed phrenology (''phrenos'': mind, ''logos'': study) by his student Johann Spurzheim

Johann Gaspar Spurzheim (31 December 1776 – 10 November 1832) was a German physician who became one of the chief proponents of phrenology, which was developed c. 1800 by Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828).

Biography

Spurzheim was born near Tr ...

(1776–1832), who wrote extensively on "Drs. Gall and Spurzheim's physiognomical System." These all claimed the ability to predict traits or intelligence and were intensively practised in the 19th and the first part of the 20th century.

During the 1940s anthropometry was used by William Sheldon when evaluating his somatotype

Somatotype is a theory proposed in the 1940s by the American psychologist William Herbert Sheldon to categorize the human physique according to the relative contribution of three fundamental elements which he termed ''somatotypes'', classified by ...

s, according to which characteristics of the body can be translated into characteristics of the mind. Inspired by Cesare Lombroso

Cesare Lombroso ( , ; ; born Ezechia Marco Lombroso; 6 November 1835 – 19 October 1909) was an Italian eugenicist, criminologist, phrenologist, physician, and founder of the Italian school of criminology. He is considered the founder of m ...

's criminal anthropology, he also believed that criminality

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Cane ...

could be predicted according to the body type. A basically anthropometric division of body type

Constitution type or body type can refer to a number of attempts to classify human body shapes:

* Humours (Ayurveda)

* Somatotype of William Herbert Sheldon

* Paul Carus's character typology

* Ernst Kretschmer's character typology

* Elliot Ab ...

s into the categories endomorphic, ectomorphic

Somatotype is a theory proposed in the 1940s by the American psychologist William Herbert Sheldon to categorize the human physique according to the relative contribution of three fundamental elements which he termed ''somatotypes'', classified by ...

and mesomorphic derived from Sheldon's somatotype

Somatotype is a theory proposed in the 1940s by the American psychologist William Herbert Sheldon to categorize the human physique according to the relative contribution of three fundamental elements which he termed ''somatotypes'', classified by ...

theories is today popular among people doing weight training

Strength training, also known as weight training or resistance training, is exercise designed to improve physical strength. It is often associated with the lifting of weights. It can also incorporate techniques such as bodyweight exercises ( ...

.

Forensic anthropometry

Bertillon, Galton and criminology

In 1883, Frenchman

In 1883, Frenchman Alphonse Bertillon

Alphonse Bertillon (; 22 April 1853 – 13 February 1914) was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement, creating an identification system based on physical m ...

introduced a system of identification

Identification or identify may refer to:

*Identity document, any document used to verify a person's identity

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Identify'' (album) by Got7, 2014

* "Identify" (song), by Natalie Imbruglia, 1999

* ''Identification ...

that was named after him. The "Bertillonage" system was based on the finding that several measures of physical features, such as the dimensions of bony structures in the body, remain fairly constant throughout adult life. Bertillon concluded that when these measurements were made and recorded systematically, every individual would be distinguishable. This cites as authorities:

* Lombroso, ''Antropometria di 400 delinquenti'' (1872)

* Roberts, ''Manual of Anthropometry'' (1878)

* Ferri, ''Studi comparati di antropometria'' (2 vols., 1881–1882)

* Lombroso, ''Rughe anomale speciali ai criminali'' (1890)

* Bertillon, ''Instructions signalétiques pour l'identification anthropométrique'' (1893)

* Livi, ''Anthropometria'' (Milan, 1900)

* Fürst, ''Indextabellen zum anthropometrischen Gebrauch'' (Jena, 1902)

* ''Report of Home Office Committee on the Best Means of Identifying Habitual Criminals'' (1893–1894) Bertillon's goal was a way of identifying recidivists ("repeat offenders"). Previously police could only record general descriptions. Photography of criminals had become commonplace, but there was no easy way to sort the many thousands of photographs except by name. Bertillon's hope was that, through the use of measurements, a set of identifying numbers could be entered into a filing system installed in a single cabinet.

The system involved 10 measurements; ''height'', ''stretch'' (distance from left shoulder

The human shoulder is made up of three bones: the clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (upper arm bone) as well as associated muscles, ligaments and tendons.

The articulations between the bones of the shoulder m ...

to middle finger

The middle finger, long finger, second finger, third finger, toll finger or tall man is the third digit of the human hand, typically located between the index finger and the ring finger. It is typically the longest digit. In anatomy, it is al ...

of raised right arm), ''bust'' (torso

The torso or trunk is an anatomical terminology, anatomical term for the central part, or the core (anatomy), core, of the body (biology), body of many animals (including human beings), from which the head, neck, limb (anatomy), limbs, tail an ...

from head to seat when seated), ''head length'' (crown to forehead) and ''head width'' temple to temple) ''width'' of cheeks

The cheeks () constitute the area of the face below the eyes and between the nose and the left or right ear. ''Buccal'' means relating to the cheek. In humans, the region is innervated by the buccal nerve. The area between the inside of the che ...

, and "lengths" of the ''right ear

In vertebrates, an ear is the organ that enables hearing and (in mammals) body balance using the vestibular system. In humans, the ear is described as having three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear co ...

'', the ''left foot

The foot (: feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is an organ at the terminal part of the leg made up o ...

, middle finger

The middle finger, long finger, second finger, third finger, toll finger or tall man is the third digit of the human hand, typically located between the index finger and the ring finger. It is typically the longest digit. In anatomy, it is al ...

'', and ''cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding Noah ...

'' (elbow to tip of middle finger). It was possible, by exhaustion, to sort the cards on which these details were recorded (together with a photograph) until a small number produced the measurements of the individual sought, independently of name.

The system was soon adapted to police methods: it prevented impersonation and could demonstrate wrongdoing.

Bertillonage was before long represented in Paris by a collection of some 100,000 cards and became popular in several other countries' justice systems. England followed suit when in 1894, a committee sent to Paris to investigate the methods and its results reported favorably on the use of measurements for primary classification and recommended also the partial adoption of the system of finger prints suggested by

The system was soon adapted to police methods: it prevented impersonation and could demonstrate wrongdoing.

Bertillonage was before long represented in Paris by a collection of some 100,000 cards and became popular in several other countries' justice systems. England followed suit when in 1894, a committee sent to Paris to investigate the methods and its results reported favorably on the use of measurements for primary classification and recommended also the partial adoption of the system of finger prints suggested by Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

Galton produced over 340 papers and b ...

, then in use in Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

, where measurements were abandoned in 1897 after the fingerprint system was adopted throughout British India. Three years later England followed suit, and, as the result of a fresh inquiry ordered by the Home Office, relied upon fingerprints alone.

Bertillonage exhibited certain defects and was gradually supplanted by the system of fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfa ...

s and, latterly, genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

. Bertillon originally measured variables he thought were independent – such as forearm length and leg length – but Galton had realized that both were the result of a single causal variable (in this case, stature) and developed the statistical concept of correlation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistics ...

.

Other complications were: it was difficult to tell whether or not individuals arrested were first-time offenders; instruments employed were costly and liable to break down; skilled measurers were needed; errors were frequent and all but irremediable; and it was necessary to repeat measurements three times to arrive at a mean result.

Physiognomy

Physiognomy claimed a correlation between physical features (especially facial features) and character traits. It was made famous byCesare Lombroso

Cesare Lombroso ( , ; ; born Ezechia Marco Lombroso; 6 November 1835 – 19 October 1909) was an Italian eugenicist, criminologist, phrenologist, physician, and founder of the Italian school of criminology. He is considered the founder of m ...

(1835–1909), the founder of anthropological criminology

Anthropological criminology (sometimes referred to as criminal anthropology, literally a combination of the study of the human species and the study of criminals) is a field of offender profiling, based on perceived links between the nature of ...

, who claimed to be able to scientifically identify links between the nature of a crime and the personality or physical appearance of the offender. The originator of the concept of a " born criminal" and arguing in favor of biological determinism

Biological determinism, also known as genetic determinism, is the belief that human behaviour is directly controlled by an individual's genes or some component of their physiology, generally at the expense of the role of the environment, wheth ...

, Lombroso tried to recognize criminals by measurements of their bodies. He concluded that skull and facial features were clues to genetic criminality and that these features could be measured with craniometers and calipers with the results developed into quantitative research. A few of the 14 identified traits of a criminal included large jaw

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth ...

s, forward projection of jaw, low sloping forehead; high cheekbone

In the human skull, the zygomatic bone (from ), also called cheekbone or malar bone, is a paired irregular bone, situated at the upper and lateral part of the face and forming part of the lateral wall and floor of the orbit (anatomy), orbit, of t ...

s, flattened or upturned nose; handle-shaped ear

In vertebrates, an ear is the organ that enables hearing and (in mammals) body balance using the vestibular system. In humans, the ear is described as having three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear co ...

s; hawk-like nose

A nose is a sensory organ and respiratory structure in vertebrates. It consists of a nasal cavity inside the head, and an external nose on the face. The external nose houses the nostrils, or nares, a pair of tubes providing airflow through the ...

s or fleshy lip

The lips are a horizontal pair of soft appendages attached to the jaws and are the most visible part of the mouth of many animals, including humans. Mammal lips are soft, movable and serve to facilitate the ingestion of food (e.g. sucklin ...

s; hard shifty eyes; scanty beard or baldness; insensitivity to pain; long arms, and so on.

Phylogeography, race and human origins

Phylogeography is the science of identifying and tracking major human migrations, especially in prehistoric times. Linguistics can follow the movement of languages and archaeology can follow the movement of artefact styles but neither can tell whether a culture's spread was due to a source population's physically migrating or to a destination population's simply copying the technology and learning the language. Anthropometry was used extensively by anthropologists studying human and racial origins: some attempted racial differentiation and

Phylogeography is the science of identifying and tracking major human migrations, especially in prehistoric times. Linguistics can follow the movement of languages and archaeology can follow the movement of artefact styles but neither can tell whether a culture's spread was due to a source population's physically migrating or to a destination population's simply copying the technology and learning the language. Anthropometry was used extensively by anthropologists studying human and racial origins: some attempted racial differentiation and classification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

, often seeking ways in which certain races were inferior to others. Nott translated Arthur de Gobineau

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau (; 14 July 1816 – 13 October 1882) was a French writer and diplomat who is best known for helping introduce scientific race theory and "racial demography", and for developing the theory of the Aryan master race and N ...

's ''An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races

''An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races'' (originally: ''Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines),'' published between 1853 and 1855, is a racialist work of French diplomat and writer Arthur de Gobineau. It argues that there are i ...

'' (1853–1855), a founding work of racial segregationism that made three main divisions between races, based not on colour but on climatic conditions and geographic location, and privileged the "Aryan" race. Science has tested many theories aligning race and personality, which have been current since Boulainvilliers (1658–1722) contrasted the '' Français'' (French people), alleged descendants of the Nordic Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

, and members of the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, to the Third Estate

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and ...

, considered to be indigenous Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization (cultural), Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire in Roman Gaul. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, Roman culture, language ...

people subordinated by right of conquest

The right of conquest was historically a right of ownership to land after immediate possession via force of arms. It was recognized as a principle of international law that gradually deteriorated in significance until its proscription in the af ...

.

François Bernier

François Bernier (25 September 162022 September 1688) was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed (14 October 165820 February 1670) for around 12 years in India.

His 1684 publication "Nouv ...

, Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

and Blumenbach had examined multiple observable human characteristics in search of a typology. Bernier based his racial classification on physical type which included hair shape, nose shape and skin color. Linnaeus based a similar racial classification scheme. As anthropologists gained access to methods of skull measure they developed racial classification based on skull shape.

Theories of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

became popular, one prominent figure being Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), who in ''L'Aryen et son rôle social'' ("The Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

and his social role", 1899) divided humanity into various, hierarchized, different " races", spanning from the "Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

white race, dolichocephalic" to the "brachycephalic" (short and broad-headed) race. Between these Vacher de Lapouge identified the "'' Homo europaeus'' (Teutonic, Protestant, etc.), the "'' Homo alpinus''" (Auvergnat

(; ) or (endonym: ) is a northern dialect of Occitan spoken in central and southern France, in particular in the former administrative region of Auvergne.

Currently, research shows that there is not really a true Auvergnat dialect but rath ...

, Turkish, etc.) and the "'' Homo mediterraneus''" ( Napolitano, Andalus, etc.). "Homo africanus" (Congo, Florida) was excluded from discussion. His racial classification ("Teutonic", "Alpine" and "Mediterranean") was also used by William Z. Ripley

William Zebina Ripley (October 13, 1867 – August 16, 1941) was an American economist, lecturer at Columbia University, professor of economics at MIT, professor of political economy at Harvard University, and anthropologist of race. Ripley was f ...

(1867–1941) who, in '' The Races of Europe'' (1899), made a map of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

according to the cephalic index of its inhabitants.

Vacher de Lapouge became one of the leading inspirations of Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and Nazi ideology

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was freque ...

. Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

relied on anthropometric measurements to distinguish Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

s from Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s and many forms of anthropometry were used for the advocacy of eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

. During the 1920s and 1930s, though, members of the school of cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term ...

of Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

began to use anthropometric approaches to discredit the concept of fixed biological race. Boas used the cephalic index to show the influence of environmental factors. Researches on skulls and skeletons eventually helped liberate 19th century European science from its ethnocentric

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

bias."Cultural Biases Reflected in the Hominid Fossil Record" (history), by Joshua Barbach and Craig Byron, 2005, ''ArchaeologyInfo.com'' webpageArchaeologyInfo-003

. This school of physical anthropology generally went into decline during the 1940s.

Race and brain size

Several studies have demonstrated correlations between race and brain size, with varying results. In some studies, Caucasians were reported to have larger brains than other racial groups, whereas in recent studies and reanalysis of previous studies, East Asians were reported as having larger brains and skulls. More common among the studies was the report that Africans had smaller skulls than either Caucasians or East Asians. Criticisms have been raised against a number of these studies regarding questionable methods. In ''Crania Americana'' Morton claimed that Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Indians were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches. In 1873

In ''Crania Americana'' Morton claimed that Caucasians had the biggest brains, averaging 87 cubic inches, Indians were in the middle with an average of 82 cubic inches and Negroes had the smallest brains with an average of 78 cubic inches. In 1873 Paul Broca

Pierre Paul Broca (, also , , ; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that is named after him. Broca's area is involve ...

(1824–1880) found the same pattern described by Samuel Morton's ''Crania Americana'' by weighing brains at autopsy

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of deat ...

. Other historical studies alleging a Black–White difference in brain size include Bean (1906), Mall, (1909), Pearl, (1934) and Vint (1934). But in Germany Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow ( ; ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder o ...

's study led him to denounce " Nordic mysticism" in the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( ; ; ; South Franconian German, South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, third-largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, after its capital Stuttgart a ...

. Josef Kollmann, a collaborator of Virchow, stated in the same congress that the people of Europe, be them German, Italian, English or French, belonged to a "mixture of various races," furthermore declaring that the "results of craniology" led to "struggle against any theory concerning the superiority of this or that European race".Andrea Orsucci,Ariani, indogermani, stirpi mediterranee: aspetti del dibattito sulle razze europee (1870-1914)

, '' Cromohs'', 1998 Virchow later rejected measure of skulls as legitimate means of

taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

. Paul Kretschmer

Paul Kretschmer (2 May 1866 – 9 March 1956) was a German linguist who studied the earliest history and interrelations of the Indo-European languages and showed how they were influenced by non-Indo-European languages, such as Etruscan.

Biogr ...

quoted an 1892 discussion with him concerning these criticisms, also citing Aurel von Törok's 1895 work, who basically proclaimed the failure of craniometry.

Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002) claimed Samuel Morton had fudged data and "overpacked" the skulls. A subsequent study by John Michael concluded that " ntrary to Gould's interpretation... Morton's research was conducted with integrity." In 2011 physical anthropologists at the university of, which owns Morton's collection, published a study that concluded that "Morton did not manipulate his data to support his preconceptions, contra Gould." They identified and remeasured half of the skulls used in Morton's reports, finding that in only 2% of cases did Morton's measurements differ significantly from their own and that these errors either were random or gave a larger than accurate volume to African skulls, the reverse of the bias that Dr. Gould imputed to Morton. Difference in brain size, however, does not necessarily imply differences in intelligence: women tend to have smaller brains than men yet have more neural complexity and loading in certain areas of the brain. This claim has been criticized by, among others, John S. Michael, who reported in 1988 that Morton's analysis was "conducted with integrity" while Gould's criticism was "mistaken".

Similar claims were previously made by Ho et al. (1980), who measured 1,261 brains at autopsy, and Beals et al. (1984), who measured approximately 20,000 skulls, finding the same East Asian

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

→ Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an → Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

n pattern but warning against using the findings as indicative of racial traits, "If one merely lists such means by geographical region or race, causes of similarity by genogroup and ecotype are hopelessly confounded". Rushton's findings have been criticized for confusing African-Americans with equatorial Africans, who generally have smaller craniums as people from hot climates often have slightly smaller crania. He also compared equatorial Africans from the poorest and least educated areas of Africa with Asians from the wealthiest, most educated areas and colder climates. According to Z. Z. Cernovsky Rushton's own study shows that the average cranial capacity of North American blacks is similar to that of Caucasians from comparable climatic zones, though a previous work by Rushton showed appreciable differences in cranial capacity between North Americans of different race. This is consistent with the findings of Z. Z. Cernovsky that people from different climates tend to have minor differences in brain size.

Race, identity and cranio-facial description

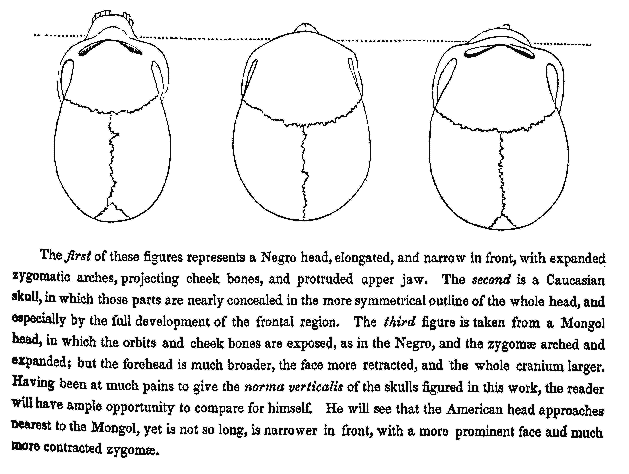

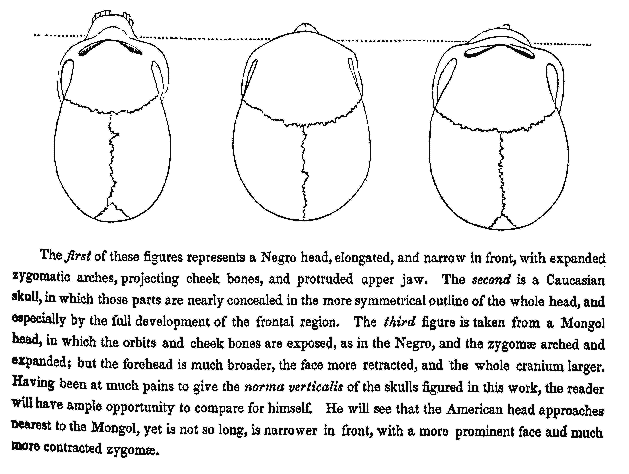

Observable craniofacial differences included: head shape (mesocephalic, brachycephalic, dolichocephalic) breadth of nasal aperture, nasal root height, sagittal crest appearance, jaw thickness, brow ridge size and forehead slope. Using this skull-based categorization, German philosopher Christoph Meiners in his The Outline of History of Mankind (1785) identified three racial groups:

*

Observable craniofacial differences included: head shape (mesocephalic, brachycephalic, dolichocephalic) breadth of nasal aperture, nasal root height, sagittal crest appearance, jaw thickness, brow ridge size and forehead slope. Using this skull-based categorization, German philosopher Christoph Meiners in his The Outline of History of Mankind (1785) identified three racial groups:

*Caucasoid

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid, Europid, or Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, dependin ...

characterized by a tall dolichocephalic skull, receded zygomas, large brow ridge and projecting-narrow nasal apertures.

*Negroid

Negroid (less commonly called Congoid) is an obsolete racial grouping of various people indigenous to Africa south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the southeast, but also to i ...

characterized by a short dolichocephalic skull, receded zygomas and wide nasal apertures.

*Mongoloid

Mongoloid () is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms ...

characterized by a medium brachycephalic skull, projecting zygomas, small brow ridge and small nasal apertures.

Ripley's ''The Races of Europe'' was rewritten in 1939 by Harvard physical anthropologist Carleton S. Coon

Carleton Stevens Coon (June 23, 1904 – June 3, 1981) was an American anthropologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He is best known for his scientific racist theories concerning the parallel evolution of human races, which ...

. Coon, a 20th-century craniofacial anthropometrist, used the technique for his ''The Origin of Races'' (New York: Knopf, 1962). Because of the inconsistencies in the old three-part system (Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid), Coon adopted a five-part scheme. He defined "Caucasoid" as a pattern of skull measurements and other phenotypical characteristics typical of populations in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

, West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, and Northeast Africa (Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

, and Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

). He discarded the term "Negroid" as misleading since it implies skin tone, which is found at low latitudes around the globe and is a product of adaptation, and defined skulls typical of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

as "Congoid" and those of Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

as "Capoid". Finally, he split "Australoid" from "Mongoloid" along a line roughly similar to the modern distinction between sinodonts in the north and sundadonts in the south. He argued that these races had developed independently of each other over the past half-million years, developing into Homo Sapiens at different periods of time, resulting in different levels of civilization. This raised considerable controversy and led the American Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) is an American organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 10,000 members, the association, based in Arlington, Virginia, includes archaeologists, cultural anthropo ...

to reject his approach without mentioning him by name.

In '' The Races of Europe'' (1939) Coon classified Caucasoids into racial sub-groups named after regions or archaeological sites such as Brünn, Borreby, Alpine, Ladogan, East Baltic, Neo-Danubian, Lappish, Mediterranean, Atlanto-Mediterranean, Irano-Afghan, Nordic, Hallstatt, Keltic, Tronder, Dinaric, Noric and Armenoid. This typological view of race, however, was starting to be seen as out-of-date at the time of publication. Coon eventually resigned from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists

The American Association of Biological Anthropologists (AABA) is an international group based in the United States which affirms itself as a professional society of biological anthropologists. The organization sponsors two peer-reviewed science ...

, while some of his other works were discounted because he would not agree with the evidence brought forward by Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

, Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

, Richard Lewontin

Richard Charles Lewontin (March 29, 1929 – July 4, 2021) was an American evolutionary biologist, mathematician, geneticist, and social commentator. A leader in developing the mathematical basis of population genetics and evolutionary theory, ...

, Leonard Lieberman and others.

The concept of biologically distinct races has been rendered obsolete by modern genetics.Templeton, A. (2016). EVOLUTION AND NOTIONS OF HUMAN RACE. In Losos J. & Lenski R. (Eds.), ''How Evolution Shapes Our Lives: Essays on Biology and Society'' (pp. 346-361). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. , see esp. p. 360: " e answer to the question whether races exist in humans is clear and unambiguous: no." That this view reflects the consensus among American anthropologists is stated in: See also: Different methods of categorizing humans yield different groups, making them non-concordant. John Relethford, The Human Species: An introduction to Biological Anthropology, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003). Neither will the craniofacial method pin-point geographic origins reliably, due to variation in skulls within a geographic region. About one-third of "white" Americans have detectable African DNA markers, and about five percent of "black" Americans have no detectable "negroid" traits at all, craniofacial or genetic. Given three Americans who self-identify and are socially accepted as white, black and Hispanic, and given that they have precisely the same Afro-European mix of ancestries (one African great-grandparent), there is no objective test that will identify their group membership without an interview."The assignment of skeletal racial origin is based principally upon stereotypical features found most frequently in the most geographically distant populations. While this is useful in some contexts (for example, sorting skeletal material of largely West African ancestry from skeletal material of largely Western European ancestry), it fails to identify populations that originate elsewhere and misrepresents fundamental patterns of human biological diversity"Forensic Misclassification of Ancient Nubian Crania: Implications for Assumptions about Human Variation, Frank L'Engle Williams, Robert L. Belcher, and George J. Armelagos

(pdf)

In popular culture

* The Bertillon system was used by the detectives inCaleb Carr

Caleb Carr (August 2, 1955 – May 23, 2024) was an American military historian and author. Carr was the second of three sons born to Lucien Carr and Francesca Von Hartz.

Carr authored '' The Alienist'', '' The Angel of Darkness'', '' Casing t ...

's novel ''The Alienist

''The Alienist'' is a crime novel by Caleb Carr first published in 1994 and is the first book in the Kreizler series. It takes place in New York City in 1896, and includes appearances by many famous figures of New York society in that era, in ...

''

See also

* * * * *References

Further reading

Anthropometric Survey of Army Personnel: Methods and Summary Statistics 1988

* ISO 7250: Basic human body measurements for technological design,

International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ; ; ) is an independent, non-governmental, international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries.

M ...

, 1998.

* ISO 8559: Garment construction and anthropometric surveys — Body dimensions, International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ; ; ) is an independent, non-governmental, international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries.

M ...

, 1989.

* ISO 15535: General requirements for establishing anthropometric databases, International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ; ; ) is an independent, non-governmental, international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries.

M ...

, 2000.

* ISO 15537: Principles for selecting and using test persons for testing anthropometric aspects of industrial products and designs, International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ; ; ) is an independent, non-governmental, international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries.

M ...

, 2003.

* ISO 20685: 3-D scanning methodologies for internationally compatible anthropometric databases, International Organization for Standardization

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO ; ; ) is an independent, non-governmental, international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries.

M ...

, 2005.

*National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a survey research program conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States, and ...

. Anthropometry Procedures Manual

'. CDC: Atlanta, USA; 2007. * *Folia Anthropologica: tudományos és módszertani folyóirat. 9: 5–17. ISSN 1786-5654 * (A classic review of human body sizes.) * Stewart A. "Kinanthropometry and body composition: A natural home for three dimensional photonic scanning". ''Journal of Sports Sciences'', March 2010; 28(5): 455–457. {{Historical definitions of race *

Anthropometry

Anthropometry (, ) refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of biological anthropology, physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthr ...

Anthropometry

Anthropometry (, ) refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of biological anthropology, physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthr ...

Criminology

Race and intelligence controversy

Biological anthropology

Human height

Human body weight

Scientific racism

Anthropometry

Anthropometry (, ) refers to the measurement of the human individual. An early tool of biological anthropology, physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purposes of understanding human physical variation, in paleoanthr ...