Beilby Porteus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Beilby Porteus (or Porteous; 8 May 1731 – 13 May 1809), successively

In 1776, Porteus was nominated as

In 1776, Porteus was nominated as

During much of the following 20 years – a time of national and international political upheaval, Porteus was in a position to influence opinion in the influential circles of the Court,

During much of the following 20 years – a time of national and international political upheaval, Porteus was in a position to influence opinion in the influential circles of the Court,

Beilby Porteus was one of the most significant, albeit under-rated church figures of the 18th century. His sermons continued to be read by many, and his legacy as a foremost abolitionist was such that his name was almost as well known in the early 19th century as those of Wilberforce and

Beilby Porteus was one of the most significant, albeit under-rated church figures of the 18th century. His sermons continued to be read by many, and his legacy as a foremost abolitionist was such that his name was almost as well known in the early 19th century as those of Wilberforce and

Death: A Poetical Essay

(1759) *A Review of the Life and Character of Archbishop Secker (1770) *On a Life of Dissipation (1770)

Sermons on Several Subjects

(1784) *An Essay on the Transfiguration of Christ (1788)

The Beneficial Effects of Christianity on the Temporal Concerns of Mankind, Proved from History and from Facts

(1806)

A Letter to the Governors, Legislatures, and Proprietors of Plantations in the British West-India Islands

(1808)

Heureux effets du Christianisme sur la félicité temporelle du genre humain

(1808) *(editor), The Works of Thomas Secker, LL.D. Late Lord Archbishop of Canterbury (1811 edition)

volume one

volume two

volume threeLectures on the Gospel of St. Matthew Delivered in the Parish Church of St. James, Westminster, in the Years 1798, 1799, 1800, and 1801

(1823 edition)

A Summary of the Principal Evidences for the Truth and Divine Origin of the Christian Revelation

(1850 edition by James Boyd)

Beilby Porteus

, ''

Bicentenary of death of Dr Beilby Porteus

* ttp://porteous.org.uk/beilby_porteus.html Bishop Porteus biography from Porteous Research Projectbr>Works of the Right Reverend Beilby Porteus, Late Bishop of London: with his Life, Beilby Porteus, 1823A Letter to the Governors, Legislatures, and Proprietors of Plantations, in the British West India Islands, Beilby Porteus, 1808

* *

Library of Beilby Porteus Papers and correspondence at Lambeth Palace LibraryBeilby Porteus

at th

Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Porteus, Beilby 1731 births 1809 deaths Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Fellows of Christ's College, Cambridge Abolitionists from London Bishops of Chester Bishops of London Deans of the Chapel Royal People educated at Ripon Grammar School 18th-century Church of England bishops 19th-century Church of England bishops Clergy from York People from Sundridge, Kent 18th-century Anglican theologians 19th-century Anglican theologians Christian abolitionists British chaplains Honorary chaplains to the King

Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in the ...

and of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, was a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

reformer and a leading abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

in England. He was the first Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

in a position of authority to seriously challenge the Church's position on slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

.

Early life

Porteus was born inYork

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

on 8 May 1731, the youngest of the 19 children of Elizabeth Jennings and Robert Porteus (''d''. 1758/9), a planter. Although the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

was of Scottish ancestry, his parents were Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

n planters who had returned to England in 1720 as a result of the economic difficulties in the province and for the sake of his father's health. Educated briefly at St Peter's School, York

St Peter's School is a mixed-sex education, co-educational Private schools in the United Kingdom, private boarding and day school (also referred to as a Public school (United Kingdom), public school), in the English City of York, with extensive ...

and later at Ripon Grammar School

Ripon Grammar School is a co-educational, boarding and day, selective grammar school in Ripon, North Yorkshire, England. It has been named top-performing state school in the north for ten years running by ''The Sunday Times''. It is one of the b ...

, he was a classics scholar at Christ's College, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, becoming a fellow in 1752. In 1759 he won the Seatonian Prize for his poem ''Death: A Poetical Essay'', a work for which he is still remembered.

He was ordained as a priest in 1757, and in 1762 was appointed as domestic chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intelligen ...

to Thomas Secker

Thomas Secker (21 September 16933 August 1768) was an Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England.

Early life and studies

Secker was born in Sibthorpe, Nottinghamshire. In 1699, he went to Richard Brown's free school in Chesterfield, ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, acting as his personal assistant at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament of the United King ...

for six years. It was during these years that it is thought he became more aware of the conditions of the enslaved Africans

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were once commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the rest of the Ancient history, ancient and Post-classical history, medieval world. When t ...

in the American colonies and the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

. He corresponded with clergy and missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

, receiving reports on the appalling conditions facing the slaves from Revd James Ramsay in the West Indies and from Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was an English scholar, philanthropist and one of the first campaigners for the Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolition of the slave trade in Britain. Born in Durham, England, Durham, he ...

, the English lawyer who had supported the cases of freed slaves in England.

In 1769 Beilby Porteus was appointed as chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

. He is listed as one of the lent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

en preachers at the Chapel Royal, Whitehall in 1771, 1773 and 1774. He was also Rector of Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

(a living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* ...

shared between the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Crown) from 1767 to 1777, and later Master of St Cross, Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

(1776–77).

He was concerned about trends within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

towards what he regarded as the watering-down of the truth of Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

and stood for doctrinal purity and opposed the anti-subscription movement, composed of theologians and scholars who, as he saw it, would have watered down cardinal Christian doctrines and beliefs and were also in favour of allowing clergy the option of subscribing to the Thirty-Nine Articles. At the same time he was prepared to suggest a compromise of a revision to some of the Articles. Always a Church of England man, he was, however, happy to work with Methodists and dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

and recognised their major contributions in evangelism

Evangelism, or witnessing, is the act of sharing the Christian gospel, the message and teachings of Jesus Christ. It is typically done with the intention of converting others to Christianity. Evangelism can take several forms, such as persona ...

and education.

He was married to Margaret Hodgson. There is no record of them having any children.

Bishop of Chester

In 1776, Porteus was nominated as

In 1776, Porteus was nominated as Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in the ...

, taking up the appointment in 1777. He lost no time in getting to grips with the problems of a diocese which had a vastly growing population within the many new centres of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, most of which were in the north-west of England, but where there were the fewest parishes. The appalling poverty and deprivation amongst the immigrant workers in new manufacturing industries represented a huge challenge to the church, resulting in vast pressure upon the parish resources. He continued to take a deep interest in the plight of West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED''), the term ''West Indian'' in 1597 described the indigenous inhabitants of the West In ...

slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, preaching and campaigning actively against the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

and taking part in many debates in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, becoming known as a noted abolitionist. He took a particular interest in the affairs of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) is a United Kingdom-based charitable organisation (registered charity no. 234518).

It was first incorporated under Royal Charter in 1701 as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Pa ...

, especially regarding the Church of England's role in the administration of the Codrington Plantations

The Codrington Plantations were two historic sugarcane producing estates on the island of Barbados, established in the 17th century by Christopher Codrington (c. 1640–1698) and his father of the same name. Sharing the characteristics of many p ...

in Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

, where around 300 slaves were owned by the Society.

Renowned as a scholar and a popular preacher, it was in 1783 that the young bishop was to first come to national attention by preaching his most famous and influential sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present context ...

.

Anniversary sermon

Porteus used the opportunity afforded by the invitation to preach the 1783 Anniversary Sermon of theSociety for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) is a United Kingdom-based charitable organisation (registered charity no. 234518).

It was first incorporated under Royal Charter in 1701 as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Pa ...

to criticise the Church of England's role in ignoring the plight of the 350 slaves on its Codrington Plantations

The Codrington Plantations were two historic sugarcane producing estates on the island of Barbados, established in the 17th century by Christopher Codrington (c. 1640–1698) and his father of the same name. Sharing the characteristics of many p ...

in Barbados and to recommend means by which the lot of slaves there could be improved.

It was an impassioned and well-reasoned plea for ''The Civilisation, Improvement and Conversion of the Negroe Slaves in the British West-India Islands Recommended'' and was preached at the church of St Mary-le-Bow

The Church of St Mary-le-Bow () is a Church of England parish church in the City of London, England. Located on Cheapside, one of the city's oldest thoroughfares, the church was founded in 1080, by Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury. Rebuilt s ...

before forty members of the society, including eleven bishops of the Church of England. When this largely fell upon deaf ears, Porteus next began work on his ''Plan for the Effectual Conversion of the Slaves of the Codrington Estate'', which he presented to the SPG committee in 1784 and, when it was turned down, again in 1789. His dismay at the rejection of his plan by the other bishops is palpable. His diary entry for the day reveals his moral outrage at the decision and at what he saw as the apparent complacency of the bishops and the committee of the society at its responsibility for the welfare of its own slaves.

These were the first challenges to the establishment in an eventual 26-year campaign to eradicate slavery in the British West Indian colonies. Porteus made a huge contribution and eventually turned to other means of achieving his aims, including writing, encouraging political initiatives, and supporting the sending of mission workers to Barbados and Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

. Deeply concerned about the lot of the slaves as a result of the reports he received, Porteus became a committed and passionate abolitionist, the most senior cleric of his day to take an active part in the campaign against slavery. He became involved with the group of abolitionists at Teston

Teston The Place Names of Kent,Judith Glover,1976,Batsford. or BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names — is a is a village and civil parish in the Maidstone (borough), Maidstone District of Kent, England. It is located on the A26 r ...

in Kent, led by Sir Charles Middleton, and soon became acquainted with William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson (28 March 1760 – 26 September 1846) was an English abolitionist, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire. He helped found the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known ...

, Henry Thornton, Zachary Macaulay

Zachary Macaulay (; 2 May 1768 – 13 May 1838) was a Scottish statistician and abolitionist who was a founder of London University and of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a Governor of British Sierra Leone.

Early life

Macaulay wa ...

and other committed activists. Many of this group were members of the so-called Clapham Sect

The Clapham Sect, or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Holy Trinity Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the Established Church, established (and do ...

of evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

social reformers and Porteus willingly lent his support to them and their campaigns.

As Wilberforce's bill for the abolition of the slave trade was brought before the British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

time and time again over 18 years from 1789, Porteus campaigned vigorously and energetically supported the campaign from within the Church of England and the bench of bishops in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

.

Bishop of London

In 1787, Porteus was translated to the bishopric of London on the advice of Prime Minister William Pitt, a position he held until his death in 1809. As is customary, he was also appointed to the Privy Council, andDean of the Chapel Royal

The Dean of the Chapel Royal, in any kingdom, can be the title of an official charged with oversight of that kingdom's chapel royal, the ecclesiastical establishment which is part of the royal household and ministers to it.

England

In England ...

. In 1788, he supported Sir William Dolben's Slave Trade Bill from the bench of bishops, and over the next quarter century he became the leading advocate within the Church of England for the abolition of slavery, lending support to such men as Wilberforce, Granville Sharp

Granville Sharp (10 November 1735 – 6 July 1813) was an English scholar, philanthropist and one of the first campaigners for the Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolition of the slave trade in Britain. Born in Durham, England, Durham, he ...

, Henry Thornton and Zachary Macaulay

Zachary Macaulay (; 2 May 1768 – 13 May 1838) was a Scottish statistician and abolitionist who was a founder of London University and of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a Governor of British Sierra Leone.

Early life

Macaulay wa ...

to secure the eventual passage of the Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the conce ...

in 1807.

In view of his passionate involvement in the anti-slavery movement and his friendship with other leading abolitionists, it was especially appropriate that, as Bishop of London, he should now find himself with official responsibility for the spiritual welfare of the British colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

overseas. He was responsible for missions to the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

, as well as to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, and towards the end of his life personally funded the sending of scriptures in the language of many peoples as far apart as Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and India.

A man of strong moral principle, Porteus was also passionately concerned about what he saw as the moral decay in the nation during the 18th century, and campaigned against trends which he saw as contributory factors, such as pleasure gardens

A pleasure garden is a park or garden that is open to the public for recreation and entertainment. Pleasure gardens differ from other public gardens by serving as venues for entertainment, variously featuring such attractions as concert halls, b ...

, theatres and the non-observance of the Lord's Day

In Christianity, the Lord's Day refers to Sunday, the traditional day of communal worship. It is the first day of the week in the Hebrew calendar and traditional Christian calendars. It is observed by most Christians as the weekly memorial of the ...

. He enlisted the support of his friend Hannah More

Hannah More (2 February 1745 – 7 September 1833) was an English religious writer, philanthropist, poet, and playwright in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick, who wrote on moral and religious subjects. Born in Bristol, she taught at ...

, former dramatist

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays, which are a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between characters and is intended for theatrical performance rather than just

reading. Ben Jonson coined the term "playwri ...

and bluestocking

''Bluestocking'' (also spaced blue-stocking or blue stockings) is a Pejorative, derogatory term for an educated, intellectual woman, originally a member of the 18th-century Blue Stockings Society from England led by the hostess and critic El ...

, to write tracts against the wickedness of the immorality and licentious behaviour which were common at these events. He vigorously opposed the spread of the principles of the French Revolution as well as what he regarded as the ungodly and dangerous doctrines of Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

's ''The Age of Reason

''The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology'' is a work by English and American political activist Thomas Paine, arguing for the philosophical position of deism. It follows in the tradition of 18th-century Brit ...

''. In 1793, at Porteus' suggestion, Hannah More published ''Village Politics'', a short pamphlet designed to counter the arguments of Paine, the first in a whole series of popular tracts designed to oppose what they saw as the prevailing immorality of the day.

Other reforms

During much of the following 20 years – a time of national and international political upheaval, Porteus was in a position to influence opinion in the influential circles of the Court,

During much of the following 20 years – a time of national and international political upheaval, Porteus was in a position to influence opinion in the influential circles of the Court, the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

, the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

and the highest echelons of Georgian society. Porteus did this, partly by encouraging debate on subjects as diverse as the slave trade, Catholic emancipation, the pay and conditions of low-paid clergy, the perceived excesses of entertainment taking place on Sundays—and by becoming a vocal supporter of William Wilberforce, Hannah More

Hannah More (2 February 1745 – 7 September 1833) was an English religious writer, philanthropist, poet, and playwright in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick, who wrote on moral and religious subjects. Born in Bristol, she taught at ...

and the Clapham Sect

The Clapham Sect, or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Holy Trinity Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the Established Church, established (and do ...

of evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

social reformers. He was also appointed as one of the members of the Board for Encouragement of Agriculture and internal Improvement in 1793. He was active in the establishment of Sunday School

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

s in every parish, an early patron of the Church Missionary Society

The Church Mission Society (CMS), formerly known as the Church Missionary Society, is a British Anglican mission society working with Christians around the world. Founded in 1799, CMS has attracted over nine thousand men and women to serve as ...

and one of the founder members of the British and Foreign Bible Society

The British and Foreign Bible Society, often known in England and Wales as simply the Bible Society, is a non-denominational Christian Bible society with charity status whose purpose is to make the Bible available throughout the world.

The ...

, of which he became vice-president.

He was a well-known and passionate advocate of personal Bible-reading and even gave his name to a system of daily devotions using the ''Porteusian Bible'', published after his death, highlighting the most important and useful passages; and was responsible for the new innovation of the use of tracts

Tract may refer to:

Geography and real estate

* Housing tract, an area of land that is subdivided into smaller individual lots

* Land lot or tract, a section of land

* Census tract, a geographic region defined for the purpose of taking a census

...

by church organisations. Always a Church of England man, Porteus was, however, happy to work with Methodists and dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

and recognised their major contributions in evangelism

Evangelism, or witnessing, is the act of sharing the Christian gospel, the message and teachings of Jesus Christ. It is typically done with the intention of converting others to Christianity. Evangelism can take several forms, such as persona ...

and education.

In 1788, George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

had again lapsed into one of his periods of mental derangement (now diagnosed as manic depression

Bipolar disorder (BD), previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that each last from days to weeks, and in some cases months. If the elevated m ...

) Andrew Roberts, George III, London 2021, Appendix pp677-680 to national concern. The following year, a Service of Thanksgiving for his recovery was held in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

, at which Porteus himself preached.

The war against Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

began in 1794 and was to drag on for another 20 years. Porteus' tenure as Bishop of London saw not only services of thanksgiving for British victories at the Battles of Cape St. Vincent, the Nile and Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

, but the great national outpouring of sorrow at the death of Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

in 1805, and his state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements o ...

service in St Paul's Cathedral in 1806. As Bishop of London, Porteus may have officiated at some of these services, although it is unlikely that he did so at Nelson's funeral, because of the Admiral's reputation as an adulterer.

After a gradual decline in his health over the previous three years, Bishop Porteus died at Fulham Palace

Fulham Palace lies on the north bank of the River Thames in Fulham, London, previously in the former English county of Middlesex. It is the site of the Manor of Fulham dating back to Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Saxon times and in the c ...

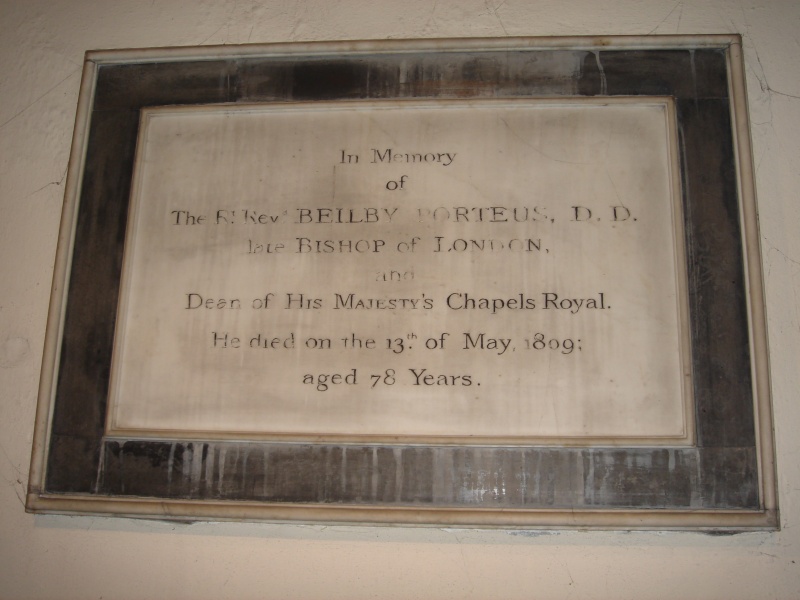

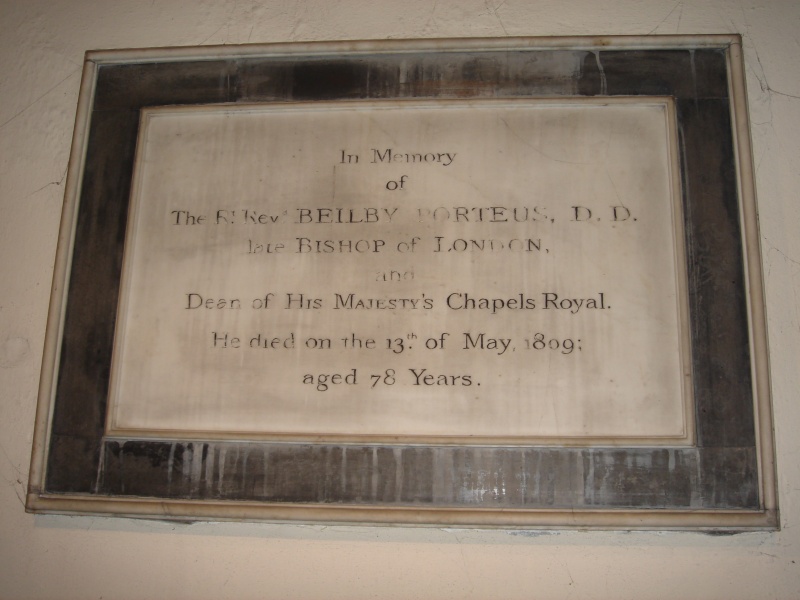

in 1809 and, according to his wishes, was buried at St Mary's church, Sundridge in Kent – a stone's throw from his country retreat in the village – a place to which he had loved to retire every autumn.

Legacy

Beilby Porteus was one of the most significant, albeit under-rated church figures of the 18th century. His sermons continued to be read by many, and his legacy as a foremost abolitionist was such that his name was almost as well known in the early 19th century as those of Wilberforce and

Beilby Porteus was one of the most significant, albeit under-rated church figures of the 18th century. His sermons continued to be read by many, and his legacy as a foremost abolitionist was such that his name was almost as well known in the early 19th century as those of Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson (28 March 1760 – 26 September 1846) was an English abolitionist, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire. He helped found the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known ...

– but a 100 years later he had become one of the 'forgotten abolitionists', and today his role has largely been ignored and his name has been consigned to the footnotes of history. His primary claim to fame in the 21st century is for his poem on ''Death'' and, possibly unfairly, as the supposed prototype for the pompous Mr Collins in Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

's ''Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is the second published novel (but third to be written) by English author Jane Austen, written when she was age 20-21, and later published in 1813.

A novel of manners, it follows the character development of Elizabe ...

''.

But it is ironic that Porteus' most lasting contribution was one for which he is little-known, the Sunday Observance Act 1780 (21 Geo. 3

This is a complete list of acts of the Parliament of Great Britain for the year 1781.

For acts passed until 1707, see the list of acts of the Parliament of England and the list of acts of the Parliament of Scotland. See also the list of acts of ...

. c. 49) (a response to what he saw as the moral decay of England), which legislated the ways in which the public were allowed to spend their recreation

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for happiness, enjoyment, amusement, ...

time at weekends

The weekdays and weekend are the complementary parts of the week, devoted to labour and rest, respectively. The legal weekdays (British English), or workweek (American English), is the part of the seven-day week devoted to working. In most o ...

for the following 200 years, until the passage of the Sunday Trading Act 1994

The Sunday Trading Act 1994 (c. 20) is an Act of Parliament (UK), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom governing the right of Retailing, shops in England and Wales to trade on a Sunday. Buying and selling on Sunday had previously been ille ...

(c. 20).

His legacy lives on, though, in the fact that the campaign which he helped to set in motion eventually led to the transformation of the Church of England into an international movement with mission

Mission (from Latin 'the act of sending out'), Missions or The Mission may refer to:

Geography Australia

*Mission River (Queensland)

Canada

*Mission, British Columbia, a district municipality

* Mission, Calgary, Alberta, a neighbourhood

* ...

and social justice

Social justice is justice in relation to the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has of ...

at its heart, appointing African, Indian and Afro-Caribbean bishops and archbishops and others from many diverse ethnic groups as its leaders.

Works

Death: A Poetical Essay

(1759) *A Review of the Life and Character of Archbishop Secker (1770) *On a Life of Dissipation (1770)

Sermons on Several Subjects

(1784) *An Essay on the Transfiguration of Christ (1788)

The Beneficial Effects of Christianity on the Temporal Concerns of Mankind, Proved from History and from Facts

(1806)

A Letter to the Governors, Legislatures, and Proprietors of Plantations in the British West-India Islands

(1808)

Heureux effets du Christianisme sur la félicité temporelle du genre humain

(1808) *(editor), The Works of Thomas Secker, LL.D. Late Lord Archbishop of Canterbury (1811 edition)

volume one

volume two

volume three

(1823 edition)

A Summary of the Principal Evidences for the Truth and Divine Origin of the Christian Revelation

(1850 edition by James Boyd)

See also

*List of abolitionist forerunners

Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), the pioneering English abolitionist, prepared a "map" of the "streams" of "forerunners and coadjutors" of the Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolitionist movement, which he published in his work, ''The Histor ...

References

*Hodgson, Robert. ''The Life of Beilby Porteus'' (1811) * *McKelvie, Graham. ''The Development of Official Anglican Interest in World Mission 1783–1809: With Special Reference to Bishop Beilby Porteus'', PhD diss. (U. Aberdeen, 1984) *Tennant, Bob. "Sentiment, Politics, and Empire: A Study of Beilby Porteus's Antislavery Sermon", in ''Discourses of Slavery and Abolition: Britain and its Colonies, 1760–1838'', ed Brycchan Carey, Markman Ellis, and Sara Salih (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) *Robinson, Andrew.Beilby Porteus

, ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

(2004), . Retrieved 2 June 2008.

People educated at St Peter's School, York

External links

*Bicentenary of death of Dr Beilby Porteus

* ttp://porteous.org.uk/beilby_porteus.html Bishop Porteus biography from Porteous Research Projectbr>Works of the Right Reverend Beilby Porteus, Late Bishop of London: with his Life, Beilby Porteus, 1823

* *

Library of Beilby Porteus

at th

Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Porteus, Beilby 1731 births 1809 deaths Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Fellows of Christ's College, Cambridge Abolitionists from London Bishops of Chester Bishops of London Deans of the Chapel Royal People educated at Ripon Grammar School 18th-century Church of England bishops 19th-century Church of England bishops Clergy from York People from Sundridge, Kent 18th-century Anglican theologians 19th-century Anglican theologians Christian abolitionists British chaplains Honorary chaplains to the King