Banded Sea Krait on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The yellow-lipped sea krait (''Laticauda colubrina''), also known as the banded sea krait or colubrine sea krait, is a

The body of the snake is subcylindrical, and is taller than it is wide. Its upper surface is typically a shade of blueish gray, while the belly is yellowish, with wide

The body of the snake is subcylindrical, and is taller than it is wide. Its upper surface is typically a shade of blueish gray, while the belly is yellowish, with wide

SeaLifeBase: Laticauda colubrina

{{Taxonbar, from=Q383702 Laticauda Reptiles of Borneo Reptiles of Cambodia Reptiles of China Reptiles of India Reptiles of Indonesia Snakes of Japan Reptiles of Korea Reptiles of Malaysia Reptiles of Myanmar Reptiles of New Zealand Reptiles of Papua New Guinea Reptiles of the Philippines Reptiles of Taiwan Reptiles of Thailand Reptiles of Vietnam Reptiles described in 1907 Taxa named by Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider Snakes of Asia Snakes of China Snakes of New Guinea Snakes of Vietnam Articles containing video clips

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of highly venomous snake

''Venomous snakes'' are species of the suborder Serpentes that are capable of producing venom, which they use for killing prey, for defense, and to assist with digestion of their prey. The venom is typically delivered by injection using hollow ...

found in tropical Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth. In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

oceanic waters. The snake has distinctive black stripes and a yellow snout, with a paddle-like tail for use in swimming.

It spends much of its time under water to hunt, but returns to land to digest, rest, and reproduce. It has very potent neurotoxic venom, which it uses to prey on eels and small fish. Because of its affinity to land, the yellow-lipped sea krait often encounters humans, but the snake is not aggressive and only attacks when feeling threatened.

Description

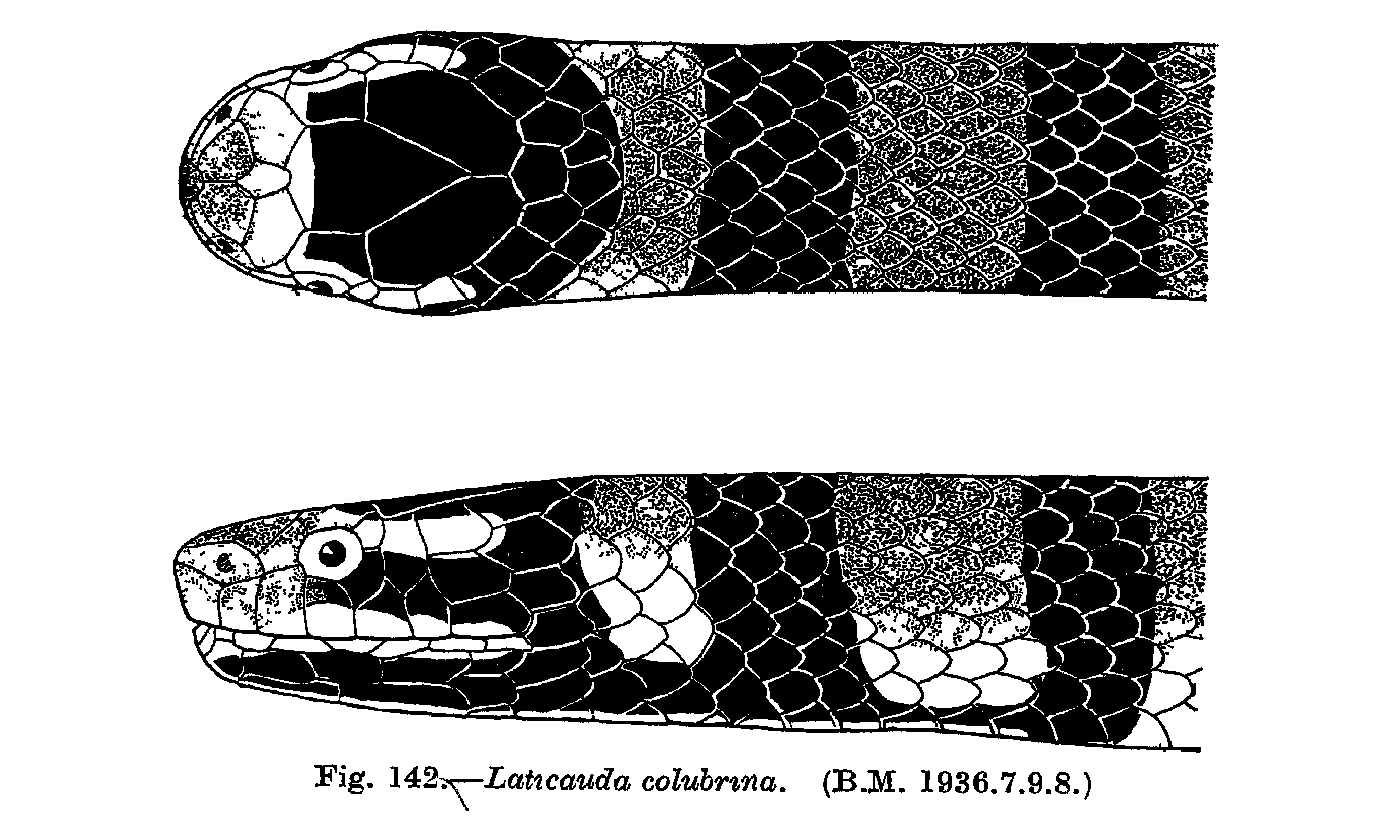

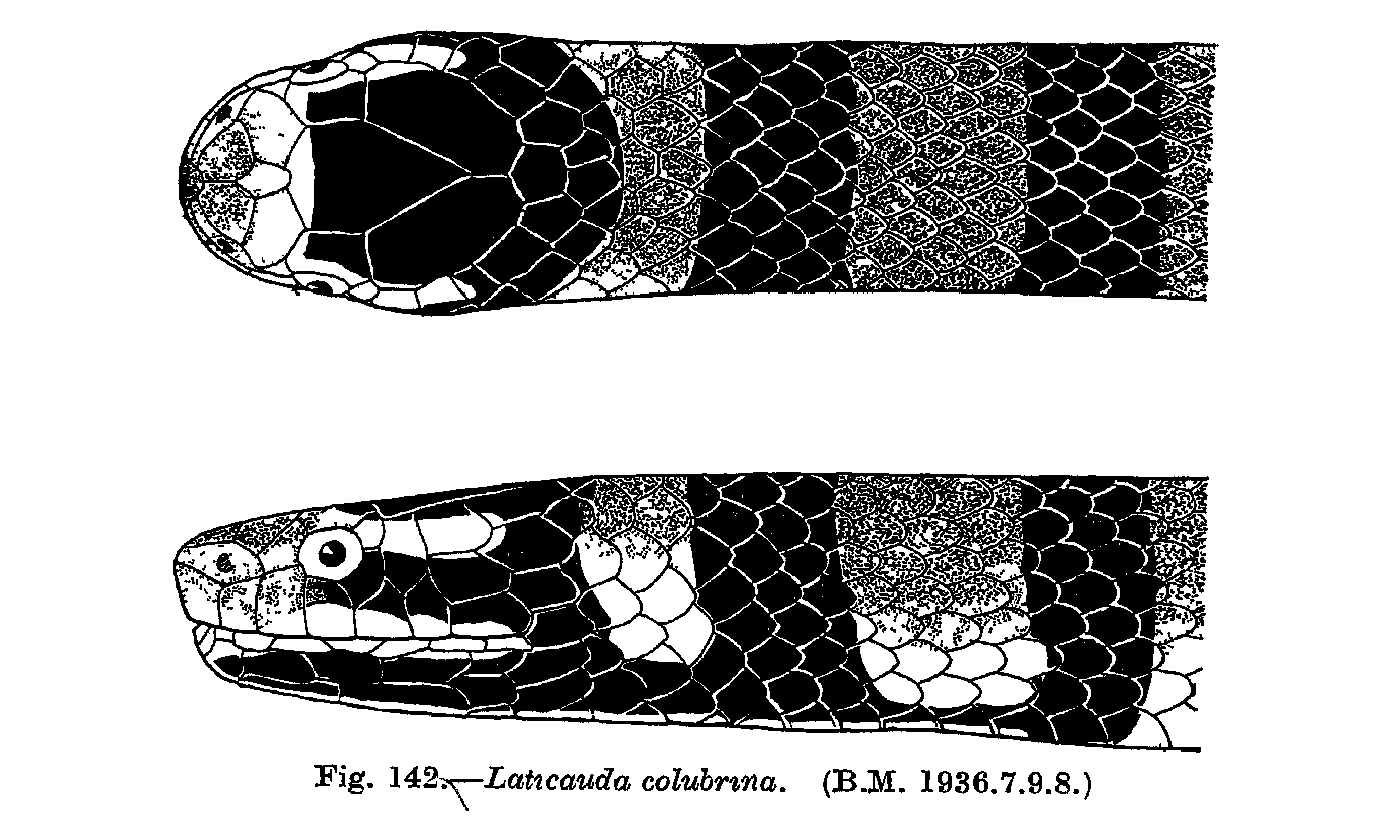

The head of a yellow-lipped sea krait is black, with lateral nostrils and an undividedrostral scale

The rostral scale, or rostral, in snakes and other scaled reptiles is the median plate on the tip of the snout that borders the mouth opening. Wright AH, Wright AA (1957). ''Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada''. Ithaca and London: ...

. The upper lip and snout are characteristically colored yellow, and the yellow color extends backward on each side of the head above the eye to the temporal scales.

The body of the snake is subcylindrical, and is taller than it is wide. Its upper surface is typically a shade of blueish gray, while the belly is yellowish, with wide

The body of the snake is subcylindrical, and is taller than it is wide. Its upper surface is typically a shade of blueish gray, while the belly is yellowish, with wide ventral scales

In snakes, the ventral scales or gastrosteges are the enlarged and transversely elongated scales that extend down the underside of the body from the neck to the anal scale. When counting them, the first is the anteriormost ventral scale that cont ...

that stretch from a third to more than half of the width of the body. Black rings of about uniform width are present throughout the length of the snake, but the rings narrow or are interrupted at the belly. The midbody is covered with 21 to 25 longitudinal rows of imbricated (overlapping) dorsal scales

In snakes, the dorsal scales are the longitudinal series of plates that encircle the body, but do not include the ventral scales. Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004). ''The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere''. Ithaca and London: Comstock Publis ...

. The dorsal and lateral scales can be used to differentiate between this species and the similar yellow-lipped New Caledonian sea krait, which typically has fewer rows of scales and scales that narrow or fail to meet (versus the yellow-lipped sea krait's ventrally meeting dark bands). The tail of the snake is paddle-shaped and adapted to swimming.

On average, the total length of a male is long, with a long tail. Females are significantly larger, with an average total length of and a tail length of .

Distribution and habitat

The yellow-lipped sea krait is widespread throughout the easternIndian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

and Western Pacific. It can be found from the eastern coast of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, along the coast of the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

in Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

, Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

, and other parts of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, to the Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago is the archipelago between Mainland Southeast Asia and Australia, and is also called Insulindia or the Indo-Australian Archipelago. The name was taken from the 19th-century European concept of a Malay race, later based ...

and to some parts of southern China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, and the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Geography of Taiwan, Taiwan: the Ryukyu Islands are divided into the Satsunan Islands (Ōsumi Islands, Ōsumi, Tokara Islands, Tokara and A ...

of Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. The species is also common near Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about ...

and other Pacific islands within its range. Vagrant individuals have been recorded in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

, and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. Six specimens have been found around the North Island

The North Island ( , 'the fish of Māui', historically New Ulster) is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but less populous South Island by Cook Strait. With an area of , it is the List ...

of New Zealand between 1880 and 2005, suspected to have come from populations based in Fiji and Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

. It is the most common sea krait identified in New Zealand, and second-most seen sea snake after the yellow-bellied sea snake

The yellow-bellied sea snake (''Hydrophis platurus'') is a highly venomous snake, venomous species of snake from the subfamily Hydrophiinae (the sea snakes) found in tropical oceanic waters around the world except for the Atlantic Ocean. For many ...

- common enough to be considered a native species, protected under the Wildlife Act 1953

Wildlife Act 1953 is an Act of Parliament in New Zealand. Under the act, the majority of native New Zealand vertebrate species are protected by law, and may not be hunted, killed, eaten or possessed. Violations may be punished with fines of up t ...

.

Venom

The venom of thiselapid

Elapidae (, commonly known as elapids , from , variant of "sea-fish") is a family (biology), family of snakes characterized by their permanently erect fangs at the front of the mouth. Most elapids are venomous, with the exception of the genus ...

, ''L. colubrina'', is a very powerful neurotoxic

Neurotoxicity is a form of toxicity in which a biological, chemical, or physical agent produces an adverse effect on the structure or function of the central and/or peripheral nervous system. It occurs when exposure to a substance – specifical ...

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

, with a subcutaneous LD50 in mice of 0.45 mg/kg body weight. The venom is an α-neurotoxin that disrupts synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

s by competing with acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (including humans) as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Par ...

for receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, similar to erabutoxins and α-bungarotoxins. In mice, lethal venom doses cause lethargy

Lethargy is a state of tiredness, sleepiness, weariness, fatigue, sluggishness, or lack of energy. It can be accompanied by depression, decreased motivation, or apathy. Lethargy can be a normal response to inadequate sleep, overexertion, overw ...

, flaccid paralysis

Flaccid paralysis is a neurological condition characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone without other obvious cause (e.g., trauma). This abnormal condition may be caused by disease or by trauma affecting the nerves associ ...

, and convulsion

A convulsion is a medical condition where the body muscles contract and relax rapidly and repeatedly, resulting in uncontrolled shaking. Because epileptic seizures typically include convulsions, the term ''convulsion'' is often used as a synony ...

s in quick succession before death. Dogs injected with lethal doses produced symptoms consistent with fatal hypertension

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a Chronic condition, long-term Disease, medical condition in which the blood pressure in the artery, arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms i ...

and cyanosis

Cyanosis is the change of Tissue (biology), tissue color to a bluish-purple hue, as a result of decrease in the amount of oxygen bound to the hemoglobin in the red blood cells of the capillary bed. Cyanosis is apparent usually in the Tissue (bi ...

observed in human sea snake bite victims.

Some varieties of eels, which are a primary food source for yellow-lipped sea kraits, may have coevolved resistance to yellow-lipped sea krait venom. '' Gymnothorax'' moray eels taken from the Caribbean, where yellow-lipped sea kraits are not endemic, died after injection with doses as small as 0.1 mg/kg body weight, but ''Gymnothorax'' individuals taken from New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

, where yellow-lipped sea kraits are endemic, were able to tolerate doses as large as 75 mg/kg without severe injury.

Behavior

Yellow-lipped sea kraits aresemiaquatic

In biology, being semi-aquatic refers to various macroorganisms that live regularly in both aquatic and terrestrial environments. When referring to animals, the term describes those that actively spend part of their daily time in water (in ...

. Juveniles stay in water and on adjacent coasts, but adults are able to move further inland and spend half their time on land and half in the ocean. Adult males are more terrestrially active during mating and hunt in shallower water, requiring more terrestrial locomotive ability. Adult females, though, are less active on land during mating and hunt in deeper water, requiring more aquatic locomotive ability. Because males are smaller, they crawl and swim faster than females.

Body adaptations, especially a paddle-like tail, help yellow-lipped sea kraits to swim. These adaptations are also found in more distantly related sea snakes (Hydrophiinae

Hydrophiinae is a subfamily of venomous snakes in the family Elapidae. It contains most sea snakes and many genera of venomous land snakes found in Australasia, such as the taipans (''Oxyuranus''), tiger snakes (''Notechis''), brown snakes (' ...

) because of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

, but because of the differences in motion between crawling and swimming, these same adaptations impede the snake's terrestrial motion. On dry land, a yellow-lipped sea krait can still move, but typically at only slightly more than a fifth of its swimming speed. In contrast, most sea snakes other than ''Laticauda'' spp. are virtually stranded on dry land.

When hunting, yellow-lipped sea kraits frequently head into deep water far from land, but return to land to digest meals, shed skin

Shed Skin is an experimental restricted- Python (3.8+) to C++ programming language compiler. It can translate pure, but implicitly statically typed Python programs into optimized C++. It can generate stand-alone programs or extension modules t ...

, and reproduce. Individuals return to their specific home islands, exhibiting philopatry

Philopatry is the tendency of an organism to stay in or habitually return to a particular area. The causes of philopatry are numerous, but natal philopatry, where animals return to their birthplace to breed, may be the most common. The term derives ...

. When yellow-lipped sea kraits on Fijian islands were relocated to different islands 5.3 km away, all recaptured individuals were found on their home islands in an average of 30.7 days.

Yellow-lipped sea kraits collected near the tip of Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

had heavy tick infections.

Hunting and diet

Hunting is often performed alone, but ''L. colubrina'' kraits may also do so in large numbers in the company of hunting parties ofgiant trevally

The giant trevally (''Caranx ignobilis''), also known as the lowly trevally, barrier trevally, ronin jack, giant kingfish, or ''ulua'', is a species of large ocean, marine fish classified in the jack Family (biology), family, Carangidae. The gian ...

and goatfish

The goatfishes are ray-finned fish of the family Mullidae, the only family in the suborder Mulloidei of the order Syngnathiformes. The family is also sometimes referred to as the red mullets, which also refers more narrowly to the genus '' Mul ...

. This cooperative hunting technique is similar to that of the moray eel

Moray eels, or Muraenidae (), are a family (biology), family of eels whose members are found worldwide. There are approximately 200 species in 15 genera which are almost exclusively Marine (ocean), marine, but several species are regu ...

, with the yellow-lipped sea kraits flushing out prey from narrow crevices and holes, and the trevally and goatfish feeding on fleeing prey.

While probing crevices with their heads, yellow-lipped sea kraits are unable to observe approaching predators and can be vulnerable. The snakes can deter predators, such as larger fish, sharks, and birds, by fooling them into thinking that their tail is their head, because the color and movement of the tail is similar to that of the snake's head. For example, the lateral aspect of the tail corresponds to the dorsal view of the head.

Yellow-lipped sea kraits primarily feed on varieties of eels (of the families Congridae, Muraenidae

Moray eels, or Muraenidae (), are a family of eels whose members are found worldwide. There are approximately 200 species in 15 genera which are almost exclusively marine, but several species are regularly seen in brackish water, ...

, and Ophichthidae

Ophichthidae is a family (biology), family of fish in the order (biology), order Anguilliformes, commonly known as the snake eels. The term "Ophichthidae" comes from Greek language, Greek ''ophis'' ("serpent") and ''ichthys'' ("fish"). Snake eels ...

), but also eat small fish (including those of the families Pomacentridae

Pomacentridae is a family of ray-finned fish, comprising the damselfishes and clownfishes. This family were formerly placed in the order Perciformes or as indeterminate percomorphs, but are now considered basal blenniiforms.

They are primaril ...

and Synodontidae). Males and females exhibit sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

in hunting behavior, as adult females, which are significantly larger than males, prefer to hunt in deeper water for larger conger eel

''Conger'' ( ) is a genus of marine congrid eels. It includes some of the largest types of eels, ranging up to or more in length, in the case of the European conger. Large congers have often been observed by divers during the day in parts of ...

s, while adult males hunt in shallower water for smaller moray eels. In addition, females hunt for only one prey item per foraging bout, while males often hunt for multiple items. After hunting, yellow-lipped sea kraits return to land to digest their prey.

Courtship and reproduction

The yellow-lipped sea krait isoviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that reproduce by depositing fertilized zygotes outside the body (i.e., by laying or spawning) in metabolically independent incubation organs known as eggs, which nurture the embryo into moving offsprings kno ...

, meaning it lays eggs that develop outside of the body.

Each year during the warmer months of September through December, males gather on land and in the water around gently sloping areas at high tide. Males prefer to mate with larger females because they produce larger and more offspring.

When a male detects a female, he chases the female and begins courtship. Females are larger and slower than males, and many males escort and intertwine around a single female. The males then align their bodies with the female and rhythmically contract; the resulting mass of snakes can remain nearly motionless for several days. After courtship, the snakes copulate for about an average of two hours.

The female yellow-lipped sea kraits then lay as many as 10 eggs per clutch. The eggs are deposited in crevices where they remain until hatching. These eggs are very rarely found in the wild; only two nests have been definitively reported throughout the entire range of the species.

Interaction with humans

Because yellow-lipped sea kraits spend much of their time on land, they are often encountered by humans. They are frequently found in the water intake and exhaust pipes of boats. They are also attracted to light and can be distracted by artificial sources of light, including hotels and other buildings, on coasts. Fewer bites from this species are recorded compared to other venomous species such as cobras and vipers, as it is less aggressive and tends to avoid humans. If they do bite, it is usually in self-defense when accidentally grabbed. Most sea snake bites occur when fishermen attempt to untangle the snakes from their fishing nets. In thePhilippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, yellow-lipped sea kraits are caught for their skin and meat; the meat is smoked and exported for use in Japanese cuisine

Japanese cuisine encompasses the regional and traditional foods of Japan, which have developed through centuries of political, economic, and social changes. The traditional cuisine of Japan (Japanese language, Japanese: ) is based on rice with m ...

. The smoked meat of a related ''Laticauda'' species, the black-banded sea krait, is used in Okinawan cuisine

is the cuisine of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. The cuisine is also known as , a reference to the Ryukyu Kingdom. Due to differences in culture, historical contact between other regions, climate, vegetables and other ingredients, Okinawan cuisine ...

to make ''irabu-jiru'' (, ''irabu soup'').

References

Further reading

* Boulenger, G.A. (1896). ''Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume III., Containing the Colubridæ (Opisthoglyphæ and Proteroglyphæ) ...'' London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). xiv + 727 pp. + Plates I-XXV. (''Platurus colubrinus'', pp. 308–309). * Das, I. (2002). ''A Photographic Guide to Snakes and other Reptiles of India''. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. 144 pp. . (''Laticauda colubrina'', p. 56). *Das, I. (2006). ''A Photographic Guide to Snakes and other Reptiles of Borneo''. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. 144 pp. . (''Laticauda colubrina'', p. 69). * * * * Schneider, J.G. (1799). ''Historiae Amphibiorum naturalis et literariae Fasciculus Primus continens Ranas, Calamitas, Bufones, Salamandras et Hydros''. Jena: F. Frommann. xiii + 264 pp. + corrigenda + Plate I. (''Hydrus colubrinus'', new species, pp. 238–240). (in Latin). * * Stejneger, L. (1907). ''Herpetology of Japan and Adjacent Territory''. United States National Museum Bulletin 58. Washington, District of Columbia: Smithsonian Institution. xx + 577 pp. (''Laticauda colubrina'', new combination, pp. 406–408). *Voris, Harold K.; Voris, Helen H. (1999). "Commuting on the tropical tides: the life of the yellow-lipped sea krait ''Laticauda colubrina'' ". ''Reptilia'' (Great Britain) (6): 23–30.External links

SeaLifeBase: Laticauda colubrina

{{Taxonbar, from=Q383702 Laticauda Reptiles of Borneo Reptiles of Cambodia Reptiles of China Reptiles of India Reptiles of Indonesia Snakes of Japan Reptiles of Korea Reptiles of Malaysia Reptiles of Myanmar Reptiles of New Zealand Reptiles of Papua New Guinea Reptiles of the Philippines Reptiles of Taiwan Reptiles of Thailand Reptiles of Vietnam Reptiles described in 1907 Taxa named by Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider Snakes of Asia Snakes of China Snakes of New Guinea Snakes of Vietnam Articles containing video clips