Ayn Rand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum; , 1905March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and philosopher. She is known for her fiction and for developing a philosophical system which she named ''

After the Russian Revolution opened up Russian universities to women, Rand was among the first to enroll at Petrograd State University, now

After the Russian Revolution opened up Russian universities to women, Rand was among the first to enroll at Petrograd State University, now

In 1932, Rand's first literary success was the sale of her screenplay '' Red Pawn'' to

In 1932, Rand's first literary success was the sale of her screenplay '' Red Pawn'' to

Following the publication of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand received many letters from readers, some of whom the book had influenced profoundly. In 1951, Rand moved from Los Angeles to New York City, where she gathered a group of these admirers who met at Rand's apartment on weekends to discuss philosophy. The group included future

Following the publication of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand received many letters from readers, some of whom the book had influenced profoundly. In 1951, Rand moved from Los Angeles to New York City, where she gathered a group of these admirers who met at Rand's apartment on weekends to discuss philosophy. The group included future

In 1964, Nathaniel Branden began an affair with the young actress Patrecia Scott, whom he later married. Nathaniel and Barbara Branden kept the affair hidden from Rand. As her relationship with Nathaniel Branden deteriorated, Rand had her husband be present for difficult conversations between her and Branden. In 1968, Rand learned about Branden's relationship with Scott. Though her romantic involvement with Nathaniel Branden was already over, Rand ended her relationship with both Brandens, and the NBI closed. She published an article in ''The Objectivist'' repudiating Nathaniel Branden for dishonesty and "irrational behavior in his private life". In subsequent years, Rand and several more of her closest associates parted company.

In 1973, Rand's younger sister Eleonora Drobisheva (née ''Rosenbaum'', 1910–1999) visited her in the US at Rand's invitation, but did not accept her lifestyle and views, as well as finding little literary merit in her works. She returned to the Soviet Union and spent the rest of her life in Leningrad, later

In 1964, Nathaniel Branden began an affair with the young actress Patrecia Scott, whom he later married. Nathaniel and Barbara Branden kept the affair hidden from Rand. As her relationship with Nathaniel Branden deteriorated, Rand had her husband be present for difficult conversations between her and Branden. In 1968, Rand learned about Branden's relationship with Scott. Though her romantic involvement with Nathaniel Branden was already over, Rand ended her relationship with both Brandens, and the NBI closed. She published an article in ''The Objectivist'' repudiating Nathaniel Branden for dishonesty and "irrational behavior in his private life". In subsequent years, Rand and several more of her closest associates parted company.

In 1973, Rand's younger sister Eleonora Drobisheva (née ''Rosenbaum'', 1910–1999) visited her in the US at Rand's invitation, but did not accept her lifestyle and views, as well as finding little literary merit in her works. She returned to the Soviet Union and spent the rest of her life in Leningrad, later

The

The

Rand's papers at The Library of Congress

Ayn Rand Lexicon

– searchable database

Frequently Asked Questions About Ayn Rand

from the

"Writings of Ayn Rand"

– from

Objectivism

Objectivism is a philosophical system named and developed by Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive a ...

''. Born and educated in Russia, she moved to the United States in 1926. After two early novels that were initially unsuccessful and two Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

plays, Rand achieved fame with her 1943 novel ''The Fountainhead

''The Fountainhead'' is a 1943 novel by Russian-American author Ayn Rand, her first major literary success. The novel's protagonist, Howard Roark, is an intransigent young architect who battles against conventional standards and refuses to com ...

''. In 1957, she published her best-selling work, the novel ''Atlas Shrugged

''Atlas Shrugged'' is a 1957 novel by Ayn Rand. It is her longest novel, the fourth and final one published during her lifetime, and the one she considered her ''magnum opus'' in the realm of fiction writing. She described the theme of ''Atlas ...

''. Afterward, until her death in 1982, she turned to non-fiction to promote her philosophy, publishing her own periodicals

Periodical literature (singularly called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) consists of Publication, published works that appear in new releases on a regular schedule (''issues'' or ''numbers'', often numerically divided into annu ...

and releasing several collections of essays.

Rand advocated reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

and rejected faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

and religion. She supported rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ...

and ethical egoism

In ethical philosophy, ethical egoism is the normative position that moral agents ''ought'' to act in their own self-interest. It differs from psychological egoism, which claims that people ''can only'' act in their self-interest. Ethical ego ...

as opposed to altruism

Altruism is the concern for the well-being of others, independently of personal benefit or reciprocity.

The word ''altruism'' was popularised (and possibly coined) by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in French, as , for an antonym of egoi ...

and hedonism

Hedonism is a family of Philosophy, philosophical views that prioritize pleasure. Psychological hedonism is the theory that all human behavior is Motivation, motivated by the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. As a form of Psycholo ...

. In politics, she condemned the initiation of force as immoral and supported ''laissez-faire'' capitalism, which she defined as the system based on recognizing individual rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

, including private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

rights. Although she opposed libertarianism

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according t ...

, which she viewed as anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, Rand is often associated with the modern libertarian movement in the United States

In the United States, libertarianism is a political philosophy promoting individual liberty. According to common meanings of conservatism and liberalism in the United States, libertarianism has been described as ''conservative'' on economic i ...

. In art, she promoted romantic realism

Romantic realism is art that combines elements of both romanticism and realism. The terms "romanticism" and "realism" have been used in varied ways, and are sometimes seen as opposed to one another.

In literature and art

The term has long standin ...

. She was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her, with a few exceptions.

Rand's books have sold over 37 million copies. Her fiction received mixed reviews from literary critics, with reviews becoming more negative for her later work. Although academic interest in her ideas has grown since her death, academic philosophers have generally ignored or rejected Rand's philosophy, arguing that she has a polemical approach and that her work lacks methodological rigor. Her writings have politically influenced some right-libertarians

Right-libertarianism,Rothbard, Murray (1 March 1971)"The Left and Right Within Libertarianism". ''WIN: Peace and Freedom Through Nonviolent Action''. 7 (4): 6–10. Retrieved 14 January 2020.Goodway, David (2006). '' Anarchist Seeds Beneath the ...

and conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

. The Objectivist movement

The Objectivist movement is a Social movement, movement of individuals who seek to study and advance Objectivism, the philosophy expounded by novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand. The movement began informally in the 1950s and consisted of students who ...

circulates her ideas, both to the public and in academic settings.

Life and career

Early life

Rand was born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum on February2, 1905, into a Jewishbourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

family living in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, which was then the capital of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

. She was the eldest of three daughters of Zinovy Zakharovich Rosenbaum, a pharmacist, and Anna Borisovna (). She was 12 when the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

and the rule of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

under Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

disrupted her family's lives. Her father's pharmacy was nationalized, and the family fled to Yevpatoria

Yevpatoria (; ; ; ) is a city in western Crimea, north of Kalamita Bay. Yevpatoria serves as the administrative center of Yevpatoria Municipality, one of the districts (''raions'') into which Crimea is divided. It had a population of

His ...

in Crimea, which was initially under the control of the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

during the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. After graduating high school there in June 1921, she returned with her family to Petrograd, as Saint Petersburg was then named, where they faced desperate conditions, occasionally nearly starving.

After the Russian Revolution opened up Russian universities to women, Rand was among the first to enroll at Petrograd State University, now

After the Russian Revolution opened up Russian universities to women, Rand was among the first to enroll at Petrograd State University, now Saint Petersburg State University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBGU; ) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter the Great, the university from the be ...

. At 16, she began her studies in the department of social pedagogy

Social pedagogy describes a holistic and relationship-centred way of working in care and educational settings with people across the course of their lives. In many countries across Europe (and increasingly beyond), it has a long-standing traditio ...

, majoring in history. She was one of many bourgeois students purged from the university shortly before graduating. After complaints from a group of visiting foreign scientists, many purged students, including Rand, were reinstated.

In October 1924, she graduated from the renamed Leningrad State University. She then studied for a year at the State Technicum for Screen Arts in Leningrad. For an assignment, Rand wrote an essay about the Polish actress Pola Negri

Pola Negri (; born Barbara Apolonia Chałupiec ; 3 January 1897 – 1 August 1987) was a Polish stage and film actress and singer. She achieved worldwide fame during the silent and golden eras of Hollywood and European film for her tragedienn ...

. It became her first published work. She decided her professional surname for writing would be ''Rand'', and she adopted the first name ''Ayn'' (pronounced ).

In late 1925, Rand was granted a visa

Visa most commonly refers to:

* Travel visa, a document that allows entry to a foreign country

* Visa Inc., a US multinational financial and payment cards company

** Visa Debit card issued by the above company

** Visa Electron, a debit card

** Vi ...

to visit relatives in Chicago. She arrived in New York City on February19, 1926. Intent on staying in the United States to become a screenwriter, she lived for a few months with her relatives learning English before moving to Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

, California.

In Hollywood a chance meeting with director Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American filmmaker and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of American cinema and the most co ...

led to work as an extra

Extra, Xtra, or The Extra may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Film

* The Extra (1962 film), ''The Extra'' (1962 film), a Mexican film

* The Extra (2005 film), ''The Extra'' (2005 film), an Australian film

Literature

* Extra (newspaper), ...

in his film '' The King of Kings'' and a subsequent job as a junior screenwriter. While working on ''The King of Kings'', she met the aspiring actor Frank O'Connor

Frank O'Connor (born Michael Francis O'Donovan; 17 September 1903 – 10 March 1966) was an Irish author and translator. He wrote poetry (original and translations from Irish), dramatic works, memoirs, journalistic columns and features on as ...

. They married on April15, 1929. She became a permanent American resident in July 1929 and an American citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Consti ...

on March3, 1931. She tried to bring her parents and sisters to the United States, but they could not obtain permission to emigrate. Rand's father died of a heart attack in 1939. One of her sisters and their mother died during the siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad was a Siege, military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front of World War II from 1941 t ...

.

Early fiction

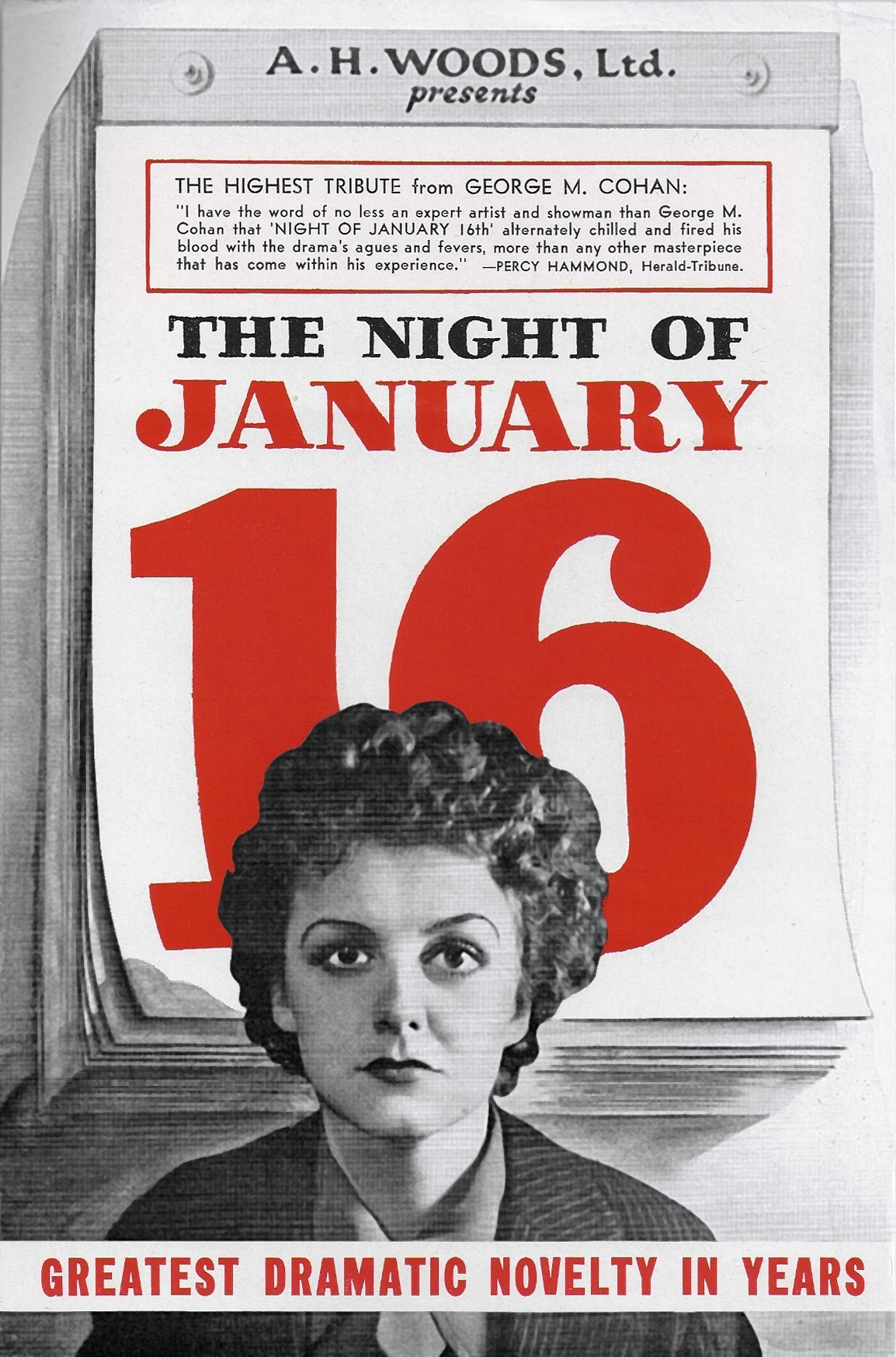

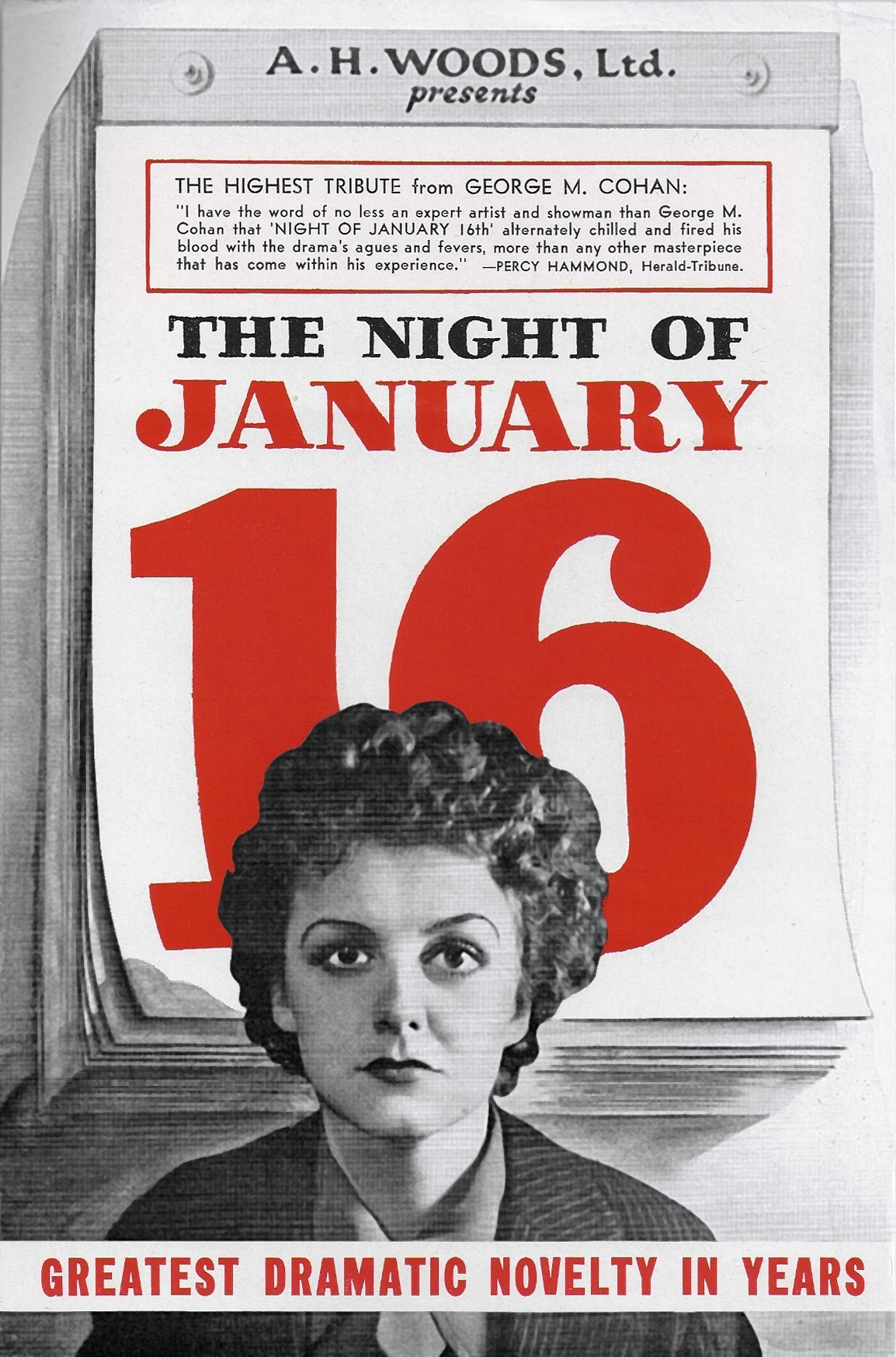

In 1932, Rand's first literary success was the sale of her screenplay '' Red Pawn'' to

In 1932, Rand's first literary success was the sale of her screenplay '' Red Pawn'' to Universal Studios Universal Studios may refer to:

* Universal Studios, Inc., an American media and entertainment conglomerate

** Universal Pictures, an American film studio

** Universal Studios Lot, a film and television studio complex

* Various theme parks operat ...

, although it was never produced. Her courtroom drama '' Night of January 16th'', first staged in Hollywood in 1934, reopened successfully on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

in 1935. Each night, a jury was selected from members of the audience. Based on its vote, one of two different endings would be performed. In December 1934, Rand and O'Connor moved to New York City so she could handle revisions for the Broadway production.

In 1936, her first novel was published, the semi-autobiographical ''We the Living

''We the Living'' is the debut novel of the Russian American novelist Ayn Rand. It is a story of life in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, post-revolutionary Russia and was Rand's first statement against communism. Rand observes in t ...

''. Set in Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, it focuses on the struggle between the individual and the state. Initial sales were slow, and the American publisher let it go out of print; however, European editions continued to sell. She adapted the story as a stage play, but the Broadway production closed in less than a week. After the success of her later novels, Rand released a revised version in 1959 that has sold over three million copies.

In December 1935, Rand started her next major novel, ''The Fountainhead

''The Fountainhead'' is a 1943 novel by Russian-American author Ayn Rand, her first major literary success. The novel's protagonist, Howard Roark, is an intransigent young architect who battles against conventional standards and refuses to com ...

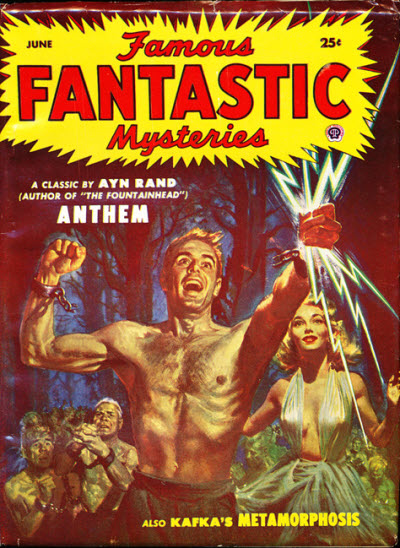

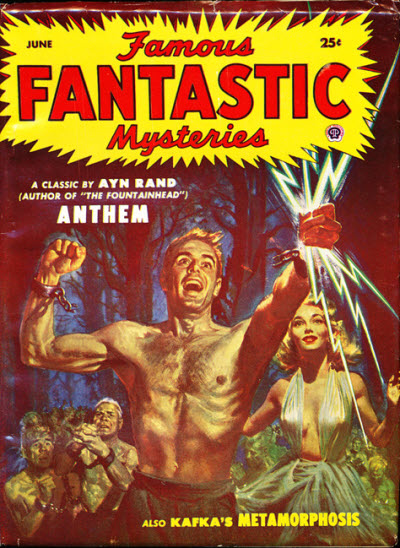

'', but took a break from it in 1937 to write her novella ''Anthem

An anthem is a musical composition of celebration, usually used as a symbol for a distinct group, particularly the national anthems of countries. Originally, and in music theory and religious contexts, it also refers more particularly to sho ...

''. The novella presents a dystopian

A dystopia (lit. "bad place") is an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives. It is an imagined place (possibly state) in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmenta ...

future world in which totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

collectivism has triumphed to such an extent that the word ''I'' has been forgotten and replaced with ''we''. Protagonists Equality 7-2521 and Liberty 5-3000

Liberty 5-3000 is a character in ''Anthem (novella), Anthem'', a 1938 Utopian and dystopian fiction, dystopian novella by Ayn Rand that is set in a rigidly collectivistic future society that assigns formulaic names to all inhabitants. A farme ...

eventually escape the collectivistic society and rediscover the word ''I''. It was published in England in 1938, but Rand could not find an American publisher at that time. As with ''We the Living'', Rand's later success allowed her to get a revised version published in 1946, and this sold over 3.5million copies.

''The Fountainhead'' and political activism

In the 1940s, Rand became politically active. She and her husband were full-time volunteers for RepublicanWendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican nominee for president. Willkie appeale ...

's 1940 presidential campaign. This work put her in contact with other intellectuals sympathetic to free-market capitalism. She became friends with journalist Henry Hazlitt

Henry Stuart Hazlitt (; November 28, 1894 – July 9, 1993) was an American journalist, economist, and philosopher known for his advocacy of free markets and classical liberal principles. Over a career spanning more than seven decades, Hazlit ...

, who introduced her to the Austrian School

The Austrian school is a Heterodox economics, heterodox Schools of economic thought, school of economic thought that advocates strict adherence to methodological individualism, the concept that social phenomena result primarily from the motivat ...

economist Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; ; September 29, 1881 – October 10, 1973) was an Austrian-American political economist and philosopher of the Austrian school. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the social contributions of classical l ...

. Despite philosophical differences with them, Rand strongly endorsed the writings of both men, and they expressed admiration for her. Mises once called her "the most courageous man in America", a compliment that particularly pleased her because he said "man" instead of "woman". Rand became friends with libertarian writer Isabel Paterson

Isabel Paterson (January 22, 1886 – January 10, 1961) was a Canadian-American libertarian writer and literary critic. Historian Jim Powell has called Paterson one of the three founding mothers of American libertarianism, along with Ros ...

. Rand questioned her about American history and politics during their many meetings, and gave Paterson ideas for her only non-fiction book, '' The God of the Machine''.

In 1943, Rand's first major success as a writer came with ''The Fountainhead'', a novel about an uncompromising architect named Howard Roark and his struggle against what Rand described as "second-handers" who attempt to live through others, placing others above themselves. Twelve publishers rejected it before Bobbs-Merrill Company

The Bobbs-Merrill Company was an American book publisher active from 1850 until 1985, and located in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Company history

The Bobbs-Merrill Company began in 1850 October 3 when Samuel Merrill bought an Indianapolis bookstore ...

accepted it at the insistence of editor Archibald Ogden, who threatened to quit if his employer did not publish it.

While completing the novel, Rand was prescribed Benzedrine

Amphetamine (contracted from alpha- methylphenethylamine) is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, and obesity; it is also used to treat binge e ...

, an amphetamine

Amphetamine (contracted from Alpha and beta carbon, alpha-methylphenethylamine, methylphenethylamine) is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, an ...

, to fight fatigue. The drug helped her to work long hours to meet her deadline for delivering the novel; afterwards, however, she was so exhausted that her doctor ordered two weeks' rest. Her use of the drug for approximately three decades may have contributed to mood swings and outbursts described by some of her later associates.

The success of ''The Fountainhead'' brought Rand fame and financial security. In 1943, she sold the film rights to Warner Bros.

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (WBEI), commonly known as Warner Bros. (WB), is an American filmed entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California and the main namesake subsidiary of Warner Bro ...

and returned to Hollywood to write the screenplay. Producer Hal B. Wallis

Harold B. Wallis (born Aaron Blum Wolowicz; October 19, 1898 – October 5, 1986) was an American film producer. He is best known for producing ''Casablanca'' (1942), ''The Adventures of Robin Hood'' (1938), and '' True Grit'' (1969), along wit ...

then hired her as a screenwriter and script-doctor for screenplays including ''Love Letters

A love letter is a romantic way to express feelings of love in written form.

Love Letter(s) or The Love Letter may also refer to:

Film and television

Film

* ''Love Letters'' (1917 film), an American drama silent film

* ''Love Letters'' ( ...

'' and '' You Came Along''. Rand became involved with the anti-Communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals and American Writers Association.

In 1947, during the Second Red Scare

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage in the United S ...

, she testified as a "friendly witness" before the United States House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 19 ...

that the 1944 film ''Song of Russia

''Song of Russia'' is a 1944 American war film made and distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The picture was credited as being directed by Gregory Ratoff, though Ratoff became ill near the end of the five-month production, and was replaced by L� ...

'' grossly misrepresented conditions in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, portraying life there as much better and happier than it was. She also wanted to criticize the lauded 1946 film ''The Best Years of Our Lives

''The Best Years of Our Lives'' (also known as ''Glory for Me'' and ''Home Again'') is a 1946 American drama film directed by William Wyler and starring Myrna Loy, Fredric March, Dana Andrews, Teresa Wright, Virginia Mayo and Harold Ru ...

'' for what she interpreted as its negative presentation of the business world but was not allowed to do so. When asked after the hearings about her feelings on the investigations' effectiveness, Rand described the process as "futile".

In 1949, after several delays, the film version of ''The Fountainhead'' was released. Although it used Rand's screenplay with minimal alterations, she "disliked the movie from beginning to end" and complained about its editing, the acting and other elements.

''Atlas Shrugged'' and Objectivism

Following the publication of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand received many letters from readers, some of whom the book had influenced profoundly. In 1951, Rand moved from Los Angeles to New York City, where she gathered a group of these admirers who met at Rand's apartment on weekends to discuss philosophy. The group included future

Following the publication of ''The Fountainhead'', Rand received many letters from readers, some of whom the book had influenced profoundly. In 1951, Rand moved from Los Angeles to New York City, where she gathered a group of these admirers who met at Rand's apartment on weekends to discuss philosophy. The group included future chair of the Federal Reserve

The chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is the head of the Federal Reserve, and is the active executive officer of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The chairman p ...

Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as the 13th chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. He worked as a private adviser and provided consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates L ...

, a young psychology student named Nathan Blumenthal (later Nathaniel Branden

Nathaniel Branden (born Nathan Blumenthal; April 9, 1930 – December 3, 2014) was a Canadian Americans, Canadian–American psychotherapy, psychotherapist and writer known for his work in the psychology of self-esteem. A former associate ...

) and his wife Barbara, and Barbara's cousin Leonard Peikoff

Leonard Sylvan Peikoff (; born October 15, 1933) is a Canadian American philosopher. He is an Objectivist and was a close associate of Ayn Rand, who designated him heir to her estate. Peikoff is a former professor of philosophy and host of a na ...

. Later, Rand began allowing them to read the manuscript drafts of her new novel, ''Atlas Shrugged''.

In 1954, her close relationship with Nathaniel Branden turned into a romantic affair. They informed both their spouses, who briefly objected, until Rand "sp out a deductive chain from which you just couldn't escape", in Barbara Branden's words, resulting in her and O'Connor's assent. Historian Jennifer Burns concludes that O'Connor was likely "the hardest hit" emotionally by the affair.

Published in 1957, ''Atlas Shrugged'' is considered Rand's ''magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

''. She described the novel's theme as "the role of the mind in man's existence—and, as a corollary, the demonstration of a new moral philosophy: the morality of rational self-interest". It advocates the core tenets of Rand's philosophy of Objectivism

Objectivism is a philosophical system named and developed by Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive a ...

and expresses her concept of human achievement. The plot involves a dystopia

A dystopia (lit. "bad place") is an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives. It is an imagined place (possibly state) in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmen ...

n United States in which the most creative industrialists, scientists, and artists respond to a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

government by going on strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

and retreating to a hidden valley where they build an independent free economy. The novel's hero and leader of the strike, John Galt, describes it as stopping "the motor of the world" by withdrawing the minds of individuals contributing most to the nation's wealth and achievements. The novel contains an exposition of Objectivism in a lengthy monologue delivered by Galt.

Despite many negative reviews, ''Atlas Shrugged'' became an international bestseller, but the reaction of intellectuals to the novel discouraged and depressed Rand. ''Atlas Shrugged'' was her last completed work of fiction, marking the end of her career as a novelist and the beginning of her role as a popular philosopher.

In 1958, Nathaniel Branden established the Nathaniel Branden Lectures, later incorporated as the Nathaniel Branden Institute (NBI), to promote Rand's philosophy through public lectures. In 1962, he and Rand co-founded ''The Objectivist Newsletter

Objectivist periodicals are a variety of academic journals, magazines, and newsletters with an editorial perspective explicitly based on Ayn Rand's philosophy of Objectivism. Several early Objectivist periodicals were edited by Rand. She later en ...

'' (later renamed ''The Objectivist'') to circulate articles about her ideas. She later republished some of these articles in book form. Rand was unimpressed by many of the NBI students and held them to strict standards, sometimes reacting coldly or angrily to those who disagreed with her.

Critics, including some former NBI students and Branden himself, later said the NBI culture was one of intellectual conformity and excessive reverence for Rand. Some described the NBI or the Objectivist movement

The Objectivist movement is a Social movement, movement of individuals who seek to study and advance Objectivism, the philosophy expounded by novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand. The movement began informally in the 1950s and consisted of students who ...

as a cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

or religion. Rand expressed opinions on a wide range of topics, from literature and music to sexuality and facial hair. Some of her followers mimicked her preferences, wearing clothes to match characters from her novels and buying furniture like hers. Some former NBI students believed the extent of these behaviors was exaggerated, and the problem was concentrated among Rand's closest followers in New York.

Later years

In the 1960s and 1970s, Rand developed and promoted her Objectivist philosophy through nonfiction and speeches, including annual lectures at theFord Hall Forum

The Ford Hall Forum is the oldest free public lecture series in the United States. Founded in 1908, it continues to host open lectures and discussions in the Greater Boston area. Some of the more well-known past speakers include Maya Angelou, Isa ...

. In answers to audience questions, she took controversial stances on political and social issues. These included supporting abortion rights, opposing the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and the military draft

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

(but condemning many draft dodgers

Conscription evasion or draft evasion (American English) is any successful attempt to elude a government-imposed obligation to serve in the military forces of one's nation. Sometimes draft evasion involves refusing to comply with the military dra ...

as "bums"), supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was fought from 6 to 25 October 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states led by Egypt and S ...

of 1973 against a coalition of Arab nations as "civilized men fighting savages", claiming European colonists had the right to invade and take land inhabited by American Indians, and calling homosexuality "immoral" and "disgusting", despite advocating the repeal of all laws concerning it. She endorsed several Republican candidates for president of the United States, most strongly Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and major general in the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve who served as a United States senator from 1953 to 1965 and 1969 to 1987, and was the Re ...

in 1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 – In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patria ...

.

In 1964, Nathaniel Branden began an affair with the young actress Patrecia Scott, whom he later married. Nathaniel and Barbara Branden kept the affair hidden from Rand. As her relationship with Nathaniel Branden deteriorated, Rand had her husband be present for difficult conversations between her and Branden. In 1968, Rand learned about Branden's relationship with Scott. Though her romantic involvement with Nathaniel Branden was already over, Rand ended her relationship with both Brandens, and the NBI closed. She published an article in ''The Objectivist'' repudiating Nathaniel Branden for dishonesty and "irrational behavior in his private life". In subsequent years, Rand and several more of her closest associates parted company.

In 1973, Rand's younger sister Eleonora Drobisheva (née ''Rosenbaum'', 1910–1999) visited her in the US at Rand's invitation, but did not accept her lifestyle and views, as well as finding little literary merit in her works. She returned to the Soviet Union and spent the rest of her life in Leningrad, later

In 1964, Nathaniel Branden began an affair with the young actress Patrecia Scott, whom he later married. Nathaniel and Barbara Branden kept the affair hidden from Rand. As her relationship with Nathaniel Branden deteriorated, Rand had her husband be present for difficult conversations between her and Branden. In 1968, Rand learned about Branden's relationship with Scott. Though her romantic involvement with Nathaniel Branden was already over, Rand ended her relationship with both Brandens, and the NBI closed. She published an article in ''The Objectivist'' repudiating Nathaniel Branden for dishonesty and "irrational behavior in his private life". In subsequent years, Rand and several more of her closest associates parted company.

In 1973, Rand's younger sister Eleonora Drobisheva (née ''Rosenbaum'', 1910–1999) visited her in the US at Rand's invitation, but did not accept her lifestyle and views, as well as finding little literary merit in her works. She returned to the Soviet Union and spent the rest of her life in Leningrad, later Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

.

In 1974, Rand had surgery for lung cancer after decades of heavy smoking. In 1976, she retired from her newsletter and, despite her lifelong objections to any government-run program (while stating that only those who opposed such programs were entitled to recoup their contributions), was enrolled in and claimed Social Security

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance ...

and Medicare with the aid of a social worker. Her activities in the Objectivist movement declined, especially after her husband died on November9, 1979. One of her final projects was a never-completed television adaptation of ''Atlas Shrugged''.

On March6, 1982, Rand died of heart failure at her home in New York City. Her funeral included a floral arrangement in the shape of a dollar sign. In her will, Rand named Peikoff as her heir.

Literary approach, influences and reception

Rand described her approach to literature as "romantic realism

Romantic realism is art that combines elements of both romanticism and realism. The terms "romanticism" and "realism" have been used in varied ways, and are sometimes seen as opposed to one another.

In literature and art

The term has long standin ...

". She wanted her fiction to present the world "as it could be and should be", rather than as it was. This approach led her to create highly stylized situations and characters. Her fiction typically has protagonists

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a ...

who are heroic individualists, depicted as fit and attractive. Her villains support duty and collectivist moral ideals. Rand often describes them as unattractive, and some have names that suggest negative traits, such as Wesley Mouch in ''Atlas Shrugged''.

Rand considered plot a critical element of literature, and her stories typically have what biographer Anne Heller described as "tight, elaborate, fast-paced plotting". Romantic triangle

A love triangle is a scenario or circumstance, usually depicted as a rivalry, in which two people are pursuing or involved in a romantic relationship with one person, or in which one person in a romantic relationship with someone is simultaneo ...

s are a common plot element in Rand's fiction; in most of her novels and plays, the main female character is romantically involved with at least two men.

Influences

In school, Rand read works byFyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influent ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, Edmond Rostand

Edmond Eugène Alexis Rostand (, , ; 1 April 1868 – 2 December 1918) was a French poet and dramatist. He is associated with neo-romanticism and is known best for his 1897 play ''Cyrano de Bergerac''. Rostand's romantic plays contrasted with th ...

, and Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, philosopher and historian. Schiller is considered by most Germans to be Germany's most important classical playwright.

He was born i ...

, who became her favorites. She considered them to be among the "top rank" of Romantic writers because of their focus on moral themes and their skill at constructing plots. Hugo was an important influence on her writing, especially her approach to plotting. In the introduction she wrote for an English-language edition of his novel ''Ninety-Three

''Ninety-Three'' (''Quatrevingt-treize'') is the last novel by the French writer Victor Hugo. Published in 1874, three years after the bloody upheaval of the Paris Commune that resulted out of popular reaction to Napoleon III's failure to win ...

'', Rand called him "the greatest novelist in world literature".

Although Rand disliked most Russian literature, her depictions of her heroes show the influence of the Russian Symbolists and other nineteenth-century Russian writing, most notably the 1863 novel '' What Is to Be Done?'' by Nikolay Chernyshevsky

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky ( – ) was a Russian literary and social critic, journalist, novelist, democrat, and socialist philosopher, often identified as a utopian socialist and leading theoretician of Russian nihilism and the N ...

. Scholars of Russian literature see in Chernyshevsky's character Rakhmetov, an "ascetic revolutionist", the template for Rand's literary heroes and heroines.

Rand's experience of the Russian Revolution and early Communist Russia influenced the portrayal of her villains. Beyond ''We the Living'', which is set in Russia, this influence can be seen in the ideas and rhetoric of Ellsworth Toohey in ''The Fountainhead'', and in the destruction of the economy in ''Atlas Shrugged''.

Rand's descriptive style echoes her early career writing scenarios and scripts for movies; her novels have many narrative descriptions that resemble early Hollywood movie scenarios. They often follow common film editing conventions, such as having a broad establishing shot

An establishing shot in filmmaking and television production sets up, or establishes, the context for a scene by showing the relationship between its important figures and objects. It is generally a long or extreme-long shot at the beginning of ...

description of a scene followed by close-up

A close-up or closeup in filmmaking, television production

A television show, TV program (), or simply a TV show, is the general reference to any content produced for viewing on a television set that is broadcast via over-the-air, s ...

details, and her descriptions of women characters often take a "male gaze

In feminist theory, the male gaze is the act of depicting women and the world in the visual arts and in literature from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the heterosex ...

" perspective.

Contemporary reviews

The first reviews Rand received were for ''Night of January 16th''. Reviews of the Broadway production were largely positive, but Rand considered even positive reviews to be embarrassing because of significant changes made to her script by the producer. Although Rand believed that ''We the Living'' was not widely reviewed, over 200 publications published approximately 125 different reviews. Overall, they were more positive than those she received for her later work. ''Anthem'' received little review attention, both for its first publication in England and for subsequent re-issues. Rand's first bestseller, ''The Fountainhead'', received far fewer reviews than ''We the Living'', and reviewers' opinions were mixed.Berliner, Michael S. "''The Fountainhead'' Reviews". In . Lorine Pruette's positive review in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', which called the author "a writer of great power" who wrote "brilliantly, beautifully and bitterly", was one that Rand greatly appreciated. There were other positive reviews, but Rand dismissed most of them for either misunderstanding her message or for being in unimportant publications. Some negative reviews said the novel was too long; others called the characters unsympathetic and Rand's style "offensively pedestrian".

''Atlas Shrugged'' was widely reviewed, and many of the reviews were strongly negative.Berliner, Michael S. "The ''Atlas Shrugged'' Reviews". In . ''Atlas Shrugged'' received positive reviews from a few publications; however, Rand scholar Mimi Reisel Gladstein later wrote that "reviewers seemed to vie with each other in a contest to devise the cleverest put-downs", with reviews including comments that it was "written out of hate" and showed "remorseless hectoring and prolixity". Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer and intelligence agent. After early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), he defected from the Soviet u ...

wrote what was later called the novel's most "notorious" review for the conservative magazine ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

''. He accused Rand of supporting a godless system (which he related to that of the Soviets

The Soviet people () were the citizens and nationals of the Soviet Union. This demonym was presented in the ideology of the country as the "new historical unity of peoples of different nationalities" ().

Nationality policy in the Soviet Union ...

), claiming, "From almost any page of ''Atlas Shrugged'', a voice can be heard ... commanding: 'To a gas chamber—go!.

Rand's nonfiction received far fewer reviews than her novels. The tenor of the criticism for her first nonfiction book, ''For the New Intellectual

''For the New Intellectual: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand'' is a 1961 work by the philosopher Ayn Rand. It is her first long non-fiction book. Much of the material consists of excerpts from Rand's novels, supplemented by a long title essay that focu ...

'', was similar to that for ''Atlas Shrugged''. Philosopher Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook (December 20, 1902 – July 12, 1989) was an American philosopher of pragmatism known for his contributions to the philosophy of history, the philosophy of education, political theory, and ethics. After embracing communism in his youth ...

likened her certainty to "the way philosophy is written in the Soviet Union", and author Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal ( ; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the Social norm, social and sexual ...

called her viewpoint "nearly perfect in its immorality". These reviews set the pattern for reaction to her ideas among liberal critics. Her subsequent books got progressively less review attention.

Academic assessments of Rand's fiction

Academic consideration of Rand as a literary figure during her life was limited. Mimi Reisel Gladstein could not find any scholarly articles about Rand's novels when she began researching her in 1973, and only three such articles appeared during the rest of the 1970s. Since her death, scholars of English and American literature have continued largely to ignore her work, although attention to her literary work has increased since the 1990s. Several academic book series about important authors cover Rand and her works, as do popular study guides likeCliffsNotes

CliffsNotes are a series of student study guides. The guides present and create literary and other works in pamphlet form or online. Detractors of the study guides claim they let students bypass reading the assigned literature. The company clai ...

and SparkNotes

SparkNotes, originally part of a website called The Spark, is a company started by Harvard students Sam Yagan, Max Krohn, Chris Coyne, and Eli Bolotin in 1999 that originally provided study guides for literature, poetry, history, film, and phil ...

. In ''The Literary Encyclopedia

''The Literary Encyclopedia'' is an online reference work first published in October 2000. It was founded as an innovative project, designed to bring the benefits of information technology to what at the time was still a largely conservative l ...

'' entry for Rand written in 2001, John David Lewis declared that "Rand wrote the most intellectually challenging fiction of her generation." In 2019, Lisa Duggan

Lisa Duggan () is Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis at New York University. Duggan was president of the American Studies Association from 2014 to 2015, presiding over the annual conference on the theme of "The Fun and the Fury: New Diale ...

described Rand's fiction as popular and influential on many readers, despite being easy to criticize for "her cartoonish characters and melodramatic plots, her rigid moralizing, her middle- to lowbrow aesthetic preferences... and philosophical strivings".

Philosophy

Rand called her philosophy "Objectivism", describing its essence as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute". She considered Objectivism asystematic philosophy

Philosophical methodology encompasses the methods used to philosophize and the study of these methods. Methods of philosophy are procedures for conducting research, creating new theories, and selecting between competing theories. In addition to ...

and laid out positions on metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

, epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

, ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, aesthetics

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste (sociology), taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Ph ...

, and political philosophy

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and Political legitimacy, legitimacy of political institutions, such as State (polity), states. This field investigates different ...

.

Metaphysics and epistemology

In metaphysics, Rand supportedphilosophical realism

Philosophical realismusually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject mattersis the view that a certain kind of thing (ranging widely from abstract objects like numbers to moral statements to the physical world ...

and opposed anything she regarded as mysticism or supernaturalism, including all forms of religion. Rand believed in free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

as a form of agent causation

Agent may refer to:

Espionage, investigation, and law

*, spies or intelligence officers

* Law of agency, laws involving a person authorized to act on behalf of another

** Agent of record, a person with a contractual agreement with an insuran ...

and rejected determinism

Determinism is the Metaphysics, metaphysical view that all events within the universe (or multiverse) can occur only in one possible way. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes ov ...

.

Rand also related her aesthetics to metaphysics by defining art as a "selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments". According to her, art allows philosophical concepts to be presented in a concrete form that can be grasped easily, thereby fulfilling a need of human consciousness. As a writer, the art form Rand focused on most closely was literature. In works such as ''The Romantic Manifesto

''The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature'' is a collection of essays regarding the nature of art by the philosopher Ayn Rand. It was first published in 1969, with a second, revised edition published in 1975. Most of the essays are repr ...

'' and '' The Art of Fiction'', she described Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

as the approach that most accurately reflects the existence of human free will.

In epistemology, Rand considered all knowledge to be based on forming higher levels of understanding from sense perception, the validity of which she considered axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

atic. She described reason as "the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man's senses". Rand rejected all claims of non-perceptual knowledge, including instinct,' 'intuition,' 'revelation,' or any form of 'just knowing. In her ''Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology

''Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology'' is a book about epistemology by the philosopher Ayn Rand (with an additional article by Leonard Peikoff). Rand considered it her most important philosophical writing. First published in installments in ...

'', Rand presented a theory of concept formation and rejected the analytic–synthetic dichotomy. She believed epistemology was a foundational branch of philosophy and considered the advocacy of reason to be the single most significant aspect of her philosophy.

Commentators, including Hazel Barnes, Nathaniel Branden, and Albert Ellis

Albert Ellis (September 27, 1913 – July 24, 2007) was an American psychologist and psychotherapist who founded rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). He held MA and PhD degrees in clinical psychology from Columbia University, and was cer ...

, have criticized Rand's focus on the importance of reason. Barnes and Ellis said Rand was too dismissive of emotion and failed to recognize its importance in human life. Branden said Rand's emphasis on reason led her to denigrate emotions and create unrealistic expectations of how consistently rational human beings should be.

Ethics and politics

In ethics, Rand argued forrational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ...

and ethical egoism

In ethical philosophy, ethical egoism is the normative position that moral agents ''ought'' to act in their own self-interest. It differs from psychological egoism, which claims that people ''can only'' act in their self-interest. Ethical ego ...

(rational self-interest), as the guiding moral principle. She said the individual should "exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself". Rand referred to egoism as "the virtue of selfishness" in her book of that title. In it, she presented her solution to the is–ought problem

The is–ought problem, as articulated by the Scottish philosopher and historian David Hume, arises when one makes claims about what ''ought'' to be that are based solely on statements about what ''is''. Hume found that there seems to be a signif ...

by describing a meta-ethical

In metaphilosophy and ethics, metaethics is the study of the nature, scope, ground, and meaning of moral judgment, ethical belief, or Value_(ethics), values. It is one of the three branches of ethics generally studied by philosophers, the others ...

theory that based morality in the needs of "man's survival qua man", which requires the use of a rational mind. She condemned ethical altruism as incompatible with the requirements of human life and happiness, and held the initiation of force was evil and irrational, writing in ''Atlas Shrugged'' that "Force and mind are opposites".

Rand's ethics and politics are the most criticized areas of her philosophy. Several authors, including Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick (; November 16, 1938 – January 23, 2002) was an American philosopher. He held the Joseph Pellegrino Harvard University Professor, University Professorship at Harvard University,atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the Existence of God, existence of Deity, deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the ...

and her rejection of altruism.

Rand's political philosophy emphasized individual rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

, including property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership), is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their Possession (law), possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely ...

. She considered ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

the only moral social system because in her view it was the only system based on protecting those rights. Rand opposed collectivism

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

and statism

In political science, statism or etatism (from French, ''état'' 'state') is the doctrine that the political authority of the state is legitimate to some degree. This may include economic and social policy, especially in regard to taxation ...

, which she considered to include many specific forms of government, such as communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, theocracy

Theocracy is a form of autocracy or oligarchy in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries, with executive and legislative power, who manage the government's ...

, and the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

. Her preferred form of government was a constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

republic that is limited to the protection of individual rights. Although her political views are often classified as conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

or libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

, Rand preferred the term "radical for capitalism". She worked with conservatives on political projects but disagreed with them over issues such as religion and ethics. Rand rejected anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

as a naive theory based in subjectivism

Subjectivism is the doctrine that "our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience", instead of shared or communal, and that there is no external or objective truth.

While Thomas Hobbes was an early proponent of subjecti ...

that would lead to collectivism in practice, and denounced libertarianism, which she associated with anarchism.

Several critics, including Nozick, have said her attempt to justify individual rights based on egoism fails. Others, like libertarian philosopher Michael Huemer

Michael Huemer (; born December 27, 1969) is an American professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has defended ethical intuitionism, direct realism, metaphysical libertarianism, phenomenal conservatism, substance d ...

, have gone further, saying that her support of egoism and her support of individual rights are inconsistent positions. Some critics, like Roy Childs, have said that her opposition to the initiation of force should lead to support of anarchism, rather than limited government.

Relationship to other philosophers

Except forAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

and classical liberals, Rand was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her. Acknowledging Aristotle as her greatest influence, Rand remarked that in the history of philosophy

The history of philosophy is the systematic study of the development of philosophical thought. It focuses on philosophy as rational inquiry based on argumentation, but some theorists also include myth, religious traditions, and proverbial lor ...

she could only recommend "three A's"—Aristotle, Aquinas, and Ayn Rand. In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace

Myron Leon Wallace (May 9, 1918 – April 7, 2012) was an American journalist, game show host, actor, and media personality. Known for his investigative journalism, he interviewed a wide range of prominent newsmakers during his seven-decade car ...

, when asked where her philosophy came from, she responded: "Out of my own mind, with the sole acknowledgement of a debt to Aristotle, the only philosopher who ever influenced me."

In an article for the ''Claremont Review of Books

The ''Claremont Review of Books'' (''CRB'') is a quarterly review of politics and statesmanship published by the conservative Claremont Institute. A typical issue consists of several book reviews and a selection of essays on topics of conserv ...

'', political scientist Charles Murray criticized Rand's claim that her only "philosophical debt" was to Aristotle. He asserted her ideas were derivative of previous thinkers such as John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

. Rand took early inspiration from Nietzsche, and scholars have found indications of this in Rand's private journals. In 1928, she alluded to his idea of the "superman

Superman is a superhero created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, which first appeared in the comic book ''Action Comics'' Action Comics 1, #1, published in the United States on April 18, 1938.The copyright date of ''Action Comics ...

" in notes for an unwritten novel whose protagonist was inspired by the murderer William Edward Hickman, whom Rand observed early in the trial before his guilt was decided by jury.

There are other indications of Nietzsche's influence in passages from the first edition of ''We the Living'', which Rand later revised, and in her overall writing style. By the time she wrote ''The Fountainhead'', Rand had turned against Nietzsche's ideas, and the extent of his influence on her even during her early years is disputed. Rand's views also may have been influenced by the promotion of egoism among the Russian nihilists

The Russian nihilist movementOccasionally, ''nihilism'' will be capitalized when referring to the Russian movement though this is not ubiquitous nor does it correspond with Russian usage. was a philosophical movement, philosophical, cultural ...

, including Chernyshevsky and Dmitry Pisarev

Dmitry Ivanovich Pisarev ( – ) was a Russian literary critic and philosopher who was a central figure of Russian nihilism. He is noted as a forerunner of Nietzschean philosophy, and for the impact his advocacy of liberation movements and natu ...

, although there is no direct evidence that she read them.

Rand considered Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

her philosophical opposite and "the most evil man in mankind's history". She believed his epistemology undermined reason and his ethics opposed self-interest. Philosophers George Walsh and Fred Seddon have argued she misinterpreted Kant and exaggerated their differences. She was critical of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and viewed his differences with Aristotle on questions of metaphysics and epistemology as the primary conflict in the history of philosophy.

Rand's relationship with contemporary philosophers was mostly antagonistic. She was not an academic and did not participate in academic discourse. She was dismissive of critics and wrote about ideas she disagreed with in a polemical manner without in-depth analysis. Academic philosophers viewed her negatively and dismissed her as an unimportant figure who should not be considered a philosopher, or given any serious response.

Early academic reaction

During Rand's lifetime, her work received little attention from academic scholars. In 1967,John Hospers

John Hospers (June 9, 1918 – June 12, 2011) was an American philosopher and political activist. Hospers was interested in Objectivism, and was once a friend of the philosopher Ayn Rand, though she later broke with him. In 1972, Hospers becam ...

discussed Rand's ethical ideas in the second edition of his textbook, ''An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis''. In 1967, Hazel Barnes included a chapter critiquing Objectivism in her book ''An Existentialist Ethics''. When the first full-length academic book about Rand's philosophy appeared in 1971, its author declared writing about Rand "a treacherous undertaking" that could lead to "guilt by association" for taking her seriously.

A few articles about Rand's ideas appeared in academic journals before her death in 1982, many of them in '' The Personalist''. One of these was "On the Randian Argument" by libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick, who criticized her meta-ethical arguments. In the same journal, other philosophers argued that Nozick misstated Rand's case. In an 1978 article responding to Nozick, Douglas Den Uyl and Douglas B. Rasmussen defended her positions, but described her style as "literary, hyperbolic and emotional".

After her death, interest in Rand's ideas increased gradually. '' The Philosophic Thought of Ayn Rand'', a 1984 collection of essays about Objectivism edited by Den Uyl and Rasmussen, was the first academic book about Rand's ideas published after her death. In one essay, political writer Jack Wheeler wrote that despite "the incessant bombast and continuous venting of Randian rage", Rand's ethics are "a most immense achievement, the study of which is vastly more fruitful than any other in contemporary thought". In 1987, the Ayn Rand Society was founded as an affiliate of the American Philosophical Association

The American Philosophical Association (APA) is the main professional organization for philosophers in the United States. Founded in 1900, its mission is to promote the exchange of ideas among philosophers, to encourage creative and scholarl ...

.

In a 1995 entry about Rand in ''Contemporary Women Philosophers'', Jenny A. Heyl described a divergence in how different academic specialties viewed Rand. She said that Rand's philosophy "is regularly omitted from academic philosophy. Yet, throughout literary academia, Ayn Rand is considered a philosopher." Writing in the 1998 edition of the ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' is an encyclopedia of philosophy edited by Edward Craig that was first published by Routledge in 1998. Originally published in both 10 volumes of print and as a CD-ROM, in 2002 it was made available on ...

'', political theorist Chandran Kukathas summarized the mainstream philosophical reception of her work in two parts. He said most commentators view her ethical argument as an unconvincing variant of Aristotle's ethics, and her political theory "is of little interest" because it is marred by an "ill-thought out and unsystematic" effort to reconcile her hostility to the state with her rejection of anarchism. In 1999, ''The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies

''The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies'' (JARS) was an academic journal devoted to studying "Rand and her times". Established in 1999, its founding co-editors were R. W. Bradford, Stephen D. Cox, and Chris Matthew Sciabarra. Since 2013, the journal had ...

'', a peer-reviewed

Peer review is the evaluation of work by one or more people with similar competencies as the producers of the work ( peers). It functions as a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the relevant field. Peer review ...

, multidisciplinary academic journal