Avalon Composite Terrane on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Avalon () is an island featured in the

In many versions of Arthurian legend, including

In many versions of Arthurian legend, including  In ''Perlesvaus'', the bodies of Guinevere and her young son Loholt are already buried in Avalon by Arthur himself during his reign. ''

In ''Perlesvaus'', the bodies of Guinevere and her young son Loholt are already buried in Avalon by Arthur himself during his reign. ''

In his final romance, ''

In his final romance, ''

Around 1190, monks at

Around 1190, monks at  The burial discovery ensured that in later romances, histories based on them and in the popular imagination, Glastonbury became increasingly identified with Avalon, an identification that continues strongly today. The later development of the legends of the Holy Grail and Joseph of Arimathea interconnected these legends with Glastonbury and with Avalon, an identification which also seems to be made in ''Perlesvaus''. The popularity of Arthurian romances has meant this area of the Somerset Levels has today become popularly described as the Vale of Avalon.

Modern writers such as

The burial discovery ensured that in later romances, histories based on them and in the popular imagination, Glastonbury became increasingly identified with Avalon, an identification that continues strongly today. The later development of the legends of the Holy Grail and Joseph of Arimathea interconnected these legends with Glastonbury and with Avalon, an identification which also seems to be made in ''Perlesvaus''. The popularity of Arthurian romances has meant this area of the Somerset Levels has today become popularly described as the Vale of Avalon.

Modern writers such as

In modern times, similar to the search for Arthur's mythical capital Camelot, a variety of sites across Britain, France and elsewhere have been put forward as being the "real Avalon". Such proposed locations include

In modern times, similar to the search for Arthur's mythical capital Camelot, a variety of sites across Britain, France and elsewhere have been put forward as being the "real Avalon". Such proposed locations include

Avalon

at The Camelot Project {{Authority control Fiction about immortality Fictional populated places Fictional valleys Glastonbury Joseph of Arimathea Locations associated with Arthurian legend Places in Celtic mythology Mythological islands

Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain (; ; ; ) is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. The 12th-century writer Geoffr ...

. It first appeared in Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth (; ; ) was a Catholic cleric from Monmouth, Wales, and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle '' The History of ...

's 1136 ''Historia Regum Britanniae

(''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a fictitious account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the List of legendary kings o ...

'' as a place of magic where King Arthur

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Great Britain, Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Wales, Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a le ...

's sword Excalibur

Excalibur is the mythical sword of King Arthur that may possess magical powers or be associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. Its first reliably datable appearance is found in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. E ...

was made and later where Arthur was taken to recover from being gravely wounded at the Battle of Camlann

The Battle of Camlann ( or ''Brwydr Camlan'') is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was mortally wounded while fighting either alongside or against Mordred, who also perished. The original legend of Caml ...

. Since then, the island has become a symbol of Arthurian mythology, similar to Arthur's castle of Camelot

Camelot is a legendary castle and Royal court, court associated with King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described ...

.

Avalon was associated from an early date with mystical practices and magical figures such as King Arthur's sorceress sister Morgan

Morgan may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Morgan – A Suitable Case for Treatment'', also called ''Morgan!'', a 1966 comedy film

* ''Morgan'' (2012 film), an American drama

* ''Morgan'' (2016 film), an American science fiction thriller

* ...

, cast as the island's ruler by Geoffrey and many later authors. Certain Briton traditions have maintained that Arthur is an eternal king who had never truly died but would return as the "once and future" king. The particular motif of his rest in Morgan's care in Avalon has become especially popular. It can be found in various versions in many French and other medieval Arthurian and other works written in the wake of Geoffrey, some of them also linking Avalon with the legend of the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (, , , ) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenanc ...

.

Avalon has often been identified as the former island of Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor is a hill near Glastonbury in the English county of Somerset, topped by the roofless tower of St Michael's Church, a Grade I Listed building (United Kingdom), listed building. The site is managed by the National Trust and has be ...

. An early and long-standing belief involves the purported discovery of Arthur's remains and their later grand reburial, in accordance with the medieval English tradition in which Arthur did not survive the fatal injuries he suffered in his final battle. Besides Glastonbury, several other alternative locations of Avalon have also been claimed or proposed. Many medieval sources also localized the place in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and European folklore connected it with the phenomenon of Fata Morgana.

Etymology

The meaning and origin of the name Avalon have been long debated by Arthurian scholars as well as Celtic andRomance

Romance may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

** Romantic orientation, the classification of the sex or gender with which a pers ...

philologists. Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth (; ; ) was a Catholic cleric from Monmouth, Wales, and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle '' The History of ...

in his pseudo-chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae

(''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a fictitious account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the List of legendary kings o ...

'' ("The History of the Kings of Britain", c. 1136) calls the place ''Insula Avallonis'', meaning the "Isle of Avallon" in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. In his later ''Vita Merlini

, or ''The Life of Merlin'', is a Latin poem in 1,529 hexameter lines written around the year 1150. Though doubts have in the past been raised about its authorship it is now widely believed to be by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It tells the story of Me ...

'' ("The Life of Merlin", c. 1150), he calls it ''Insula Pomorum'', the "Isle of Fruit Trees" (from Latin ''pōmus'' "fruit tree"). Today, the name is generally considered to be of Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

origin (a Cornish or Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

**Breton people

**Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Gale ...

origin is also possible), from Old Welsh

Old Welsh () is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic around 550, ha ...

, Old Cornish

Cornish ( Standard Written Form: or , ) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family. Along with Welsh and Breton, Cornish descends from Common Brittonic, a language once spoken widely across Great Britain. For much o ...

, or Old Breton

Breton (, , ; or in Morbihan) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language group spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albeit as a member of ...

''aball'' or ''avallen(n)'', "apple tree, fruit tree" (cf. Welsh ''afal'', from Proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly Linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed throu ...

*''abalnā'', literally "fruit-bearing (thing)").Koch, John. ''Celtic Culture: A historical encyclopedia'', ABC-CLIO 2006, p. 146.

The tradition of an "apple" island among the ancient Britons may also be related to Irish legends

Irish mythology is the body of myths indigenous to the island of Ireland. It was originally Oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era. In the History of Ireland (795–1169), early medieval era, myths were ...

of the otherworld

In historical Indo-European religion, the concept of an otherworld, also known as an otherside, is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other world/side"), a term used by Lucan in his desc ...

island home of Manannán mac Lir

or , also known as ('son of the Sea'), is a Water deity, sea god, warrior, and king of the Tír na nÓg, otherworld in Irish mythology, Gaelic (Irish, Manx, and Scottish) mythology who is one of the .

He is seen as a ruler and guardian of t ...

and Lugh

Lugh or Lug (; ) is a figure in Irish mythology. A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of supernatural beings, Lugh is portrayed as a warrior, a king, a master craftsman and a saviour.Olmsted, Garrett. ''The Gods of the Celts and the I ...

, Emain Ablach

Emain Ablach (also Emne; Middle Irish Emhain Abhlach or Eamhna; meaning "Emhain of the Apples") is a mythical island paradise in Irish mythology. It is often regarded as the realm of the sea god Manannán Mac Lir and identified with either the Is ...

(also the Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic (, Ogham, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ; ; or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic languages, Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from 600 to 900. The ...

poetic name for Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

), where ''Ablach'' means "Having Apple Trees"— from Old Irish ''aball'' ("apple") — and is similar to the Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh (, ) is the label attached to the Welsh language of the 12th to 15th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This form of Welsh developed directly from Old Welsh ().

Literature and history

Middle Welsh is ...

name ''Afallach Afallach (Old Welsh Aballac) is a man's name found in several medieval Welsh genealogies, where he is made the son of Beli Mawr. According to a medieval Welsh triad, Afallach was the father of the goddess Modron. The Welsh redactions of Geoffrey o ...

'', which was used to replace the name Avalon in medieval Welsh translations of French and Latin Arthurian tales. All are related to the Gaulish root *''aballo'' "fruit tree" (found in the place name Aballo/Aballone) and are derived from Proto-Celtic *''abal''- "apple", which is related at the Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

level to English ''apple'', Russian ''яблоко'' (''jabloko''), Latvian ''ābele'', et al.

In the early 12th century, William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury (; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a gifted historical scholar and a ...

claimed the name of Avalon came from a man called Avalloc, who once lived on this isle with his daughters. Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales (; ; ; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taught in France and visited Rome several times, meeting the Pope. He ...

similarly derived the name of Avalon from its purported former ruler, Avallo. The name is also similar to "Avallus", described by Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

in his 1st-century ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' () is a Latin work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work' ...

'' as a mysterious island where amber could be found.

Legend

Geoffrey of Monmouth

According to Geoffrey in the ''Historia'', and much subsequent literature which he inspired,King Arthur

According to legends, King Arthur (; ; ; ) was a king of Great Britain, Britain. He is a folk hero and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In Wales, Welsh sources, Arthur is portrayed as a le ...

was taken to Avalon (''Avallon'') in hope that he could be saved and recover from his mortal wounds following the tragic Battle of Camlann

The Battle of Camlann ( or ''Brwydr Camlan'') is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was mortally wounded while fighting either alongside or against Mordred, who also perished. The original legend of Caml ...

. Geoffrey first mentions Avalon as the place where Arthur's sword Excalibur

Excalibur is the mythical sword of King Arthur that may possess magical powers or be associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. Its first reliably datable appearance is found in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. E ...

(''Caliburn'') was forged.

Geoffrey dealt with the subject in more detail in the ''Vita Merlini'', in which he describes for the first time in Arthurian legend the fairy or fae-like enchantress Morgen

A Morgen (Mg) is a historical, but still occasionally used, German unit of area used in agriculture. Officially, it is no longer in use, having been supplanted by the hectare. While today it is approximately equivalent to the Prussian ''morgen' ...

(i.e. Morgan) as the chief of nine sisters

The Nine Sisters or the Morros are a chain of twenty-three, although typically only nine are included, volcanic mountains and hills in western San Luis Obispo County, Southern California. They run between Morro Bay and San Luis Obispo.

Geograph ...

(including Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Tyronoe and Thiten) who together rule Avalon. Geoffrey's telling, in the in-story narration by the bard Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Britons (Celtic people), Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the ''Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to ...

to Merlin, indicates a sea voyage was needed to get there. The description of Avalon, which is heavily indebted to the early medieval Spanish scholar Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville (; 4 April 636) was a Spania, Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Seville, archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of the 19th-century historian Charles Forbes René de Montal ...

(having been mostly derived from the section on famous islands in Isidore's work ''Etymologiae

(Latin for 'Etymologies'), also known as the ('Origins'), usually abbreviated ''Orig.'', is an etymological encyclopedia compiled by the influential Christian bishop Isidore of Seville () towards the end of his life. Isidore was encouraged t ...

'', XIV.6.8 "'' Fortunatae Insulae''"), shows the magical nature of the island:

In Layamon

Layamon or Laghamon (, ; ) – spelled Laȝamon or Laȝamonn in his time, occasionally written Lawman – was an English poet of the late 12th/early 13th century and author of the ''Brut'', a notable work that was the first to present the legend ...

's ''Brut'' version of the ''Historia'', Arthur is taken to Avalon to be healed there through means of magic water by a distinctively Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

version of Morgen: an elf

An elf (: elves) is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic peoples, Germanic folklore. Elves appear especially in Norse mythology, North Germanic mythology, being mentioned in the Icelandic ''Poetic Edda'' and the ''Prose Edda'' ...

queen of Avalon named Argante. In the ''Didot-Perceval'', Perceval

Perceval (, also written Percival, Parzival, Parsifal), alternatively called Peredur (), is a figure in the legend of King Arthur, often appearing as one of the Knights of the Round Table. First mentioned by the French author Chrétien de Tro ...

's Grail Quest

The Holy Grail (, , , ) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenanc ...

adventures include him fighting a flock of ravens that turn out to be fairy maidens from Avalon, sisters of the wife of one Urbain of the Black Thorn, in a story likely representing Geoffrey's shapeshifting Morgen and her sisters as inspired by the Welsh Modron

Modron ("mother") is a figure in Welsh tradition, known as the mother of the hero Mabon ap Modron. Both characters may have derived from earlier divine figures, in her case the Gaulish goddess Matrona. She may have been a prototype for Morgan ...

(Urbain thus being Modron's husband Urien

Urien ap Cynfarch Oer () or Urien Rheged (, Old Welsh: or , ) was a powerful sixth-century Brittonic-speaking figure who was possibly the ruler of the territory or kingdom known as Rheged. He is one of the best-known and best documented o ...

) and possibly also influenced by the Irish Mórrigan. Geoffrey's Merlin

The Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN) is an interferometer array of radio telescopes spread across England. The array is run from Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire by the University of Manchester on behalf of UK Re ...

not only never visits Avalon but is not even aware of its existence, until told about it after Arthur's delivery there by Taliesin. This would change to various degrees in the later Arthurian prose romance tradition that expanded on Merlin's association with Arthur, as well on the subject of Avalon itself.

Later medieval literature

In many versions of Arthurian legend, including

In many versions of Arthurian legend, including Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of ''Le Morte d'A ...

's compilation ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; Anglo-Norman French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

'', Morgan the Fairy and several other magical queens (numbering either three, four, or "many") arrive after the battle to take the mortally wounded Arthur from the battlefield of Camlann (Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies within the county of Wiltshire, but st ...

in the romances) to Avalon in a black boat. Besides Morgan, who by this time had already become Arthur's supernatural sibling in the popular romance tradition, they sometimes come with the Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (, , , , ) is a title used by multiple characters in the Matter of Britain, the body of medieval literature and mythology associated with the legend of King Arthur. As either actually fairy or fairy-like yet human enchantres ...

among them. The others may include the Queen of Northgales (North Wales) and the Queen of the Wasteland. In the Vulgate

The Vulgate () is a late-4th-century Bible translations into Latin, Latin translation of the Bible. It is largely the work of Saint Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels used by the Diocese of ...

''Queste'', Morgan tells Arthur of her intention to relocate to Avalon, "where the ladies who know all the magic in the world are" (''ou les dames sont qui seiuent tous les enchantemens del monde'' ), not long before his final battle. Its Welsh version also claims, within its text, to be a translation of old Latin books from Avalon, as does the French ''Perlesvaus

''Perlesvaus'', also called ''Li Hauz Livres du Graal'' (''The High Book of the Grail''), is an Old French Arthurian romance from the 13th century. It purports to be a continuation of romance (heroic literature)">romance from the 13th century. ...

''. In Lope Garcia de Salazar's Spanish summary of the Post-Vulgate

The Post-Vulgate Cycle, also known as the Post-Vulgate Arthuriad, the Post-Vulgate ''Roman du Graal'' (''Romance of the Grail'') or the Pseudo-Robert de Boron Cycle, is one of the major Old French -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at whi ...

''Roman du Graal'', Avalon is conflated with (and explicitly named as) the mythological Island of Brasil, said to be located west of Ireland and afterwards forever hidden in mist by Morgan's enchantment.

In some texts, Arthur's fate in Avalon is left untold or uncertain. In the '' Vera historia de morte Arthuri'' ("True story of the death of Arthur"), for instance, Arthur is taken by four of his men to Avalon in the land of Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

(north-west Wales), where he is about to die but then mysteriously disappears in a mist amongst sudden great storm. ''Lanzelet

''Lanzelet'' is a medieval romance written by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven after 1194.

History

The poem consists of about 9,400 lines arranged in 4-stressed Middle High German couplets. It survives complete in two manuscripts and in fragmentary fo ...

'' tells of Loholt (''Loüt'') having left with Arthur to Avalon "whence the Bretons still expect both of them evermore." Other times, Arthur's eventual death is explicitly confirmed, as it happens in the Stanzaic ''Morte Arthur'', where the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

later receives the dead king's body from Morgan and buries it at Glastonbury

Glastonbury ( , ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbury is less than across the River ...

. In the telling from Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'', relatively devoid of supernatural elements, it is not Morgan but the renowned physicians from Salerno who try, and fail, to save Arthur's life in Avalon. Conversely, the ''Gesta Regum Britanniae

The () is a Latin epic written at some time between 1235 and 1254, and attributed to a Breton monk, William of Rennes.

The ''Gesta'' is fundamentally a versification of Geoffrey of Monmouth's in Latin epic hexameters. It retains Geoffrey's ove ...

'', an early rewrite of Geoffrey's ''Historia'', states (in the present tense) that Morgan "keeps his healed body for her very own and they now live together." In a similar narrative, the chronicle ''Draco Normannicus

The (Norman Dragon) is a chronicle written by Étienne de Rouen (Stephen of Rouen), a Norman Benedictine monk from Bec-Hellouin. Considered Étienne's principal work, it survives in the Vatican Library. The manuscript was initially anonymous, ho ...

'' contains a fictional letter from King Arthur to Henry II of England

Henry II () was King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with the ...

, claiming Arthur having been healed of his wounds and made immortal by his "deathless (eternal) nymph

A nymph (; ; sometimes spelled nymphe) is a minor female nature deity in ancient Greek folklore. Distinct from other Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature; they are typically tied to a specific place, land ...

" sister Morgan in the holy island of Avalon (''Avallonis eas insula sacra'') through the island's miraculous herbs. This is reminiscent of the British tradition mentioned by Gervase of Tilbury

Gervase of Tilbury (; 1150–1220) was an English canon lawyer, statesman and cleric. He enjoyed the favour of Henry II of England and later of Henry's grandson, Emperor Otto IV, for whom he wrote his best known work, the '' Otia Imperialia''.

...

as having Morgan still healing Arthur's wounds opening annually ever since on the Isle of Avalon (''Davalim''). In the ''Didot-Perceval'', Arthur's sister Morgan is left to tends his mortal wounds in Avalon while the Britons wait for him (as told by him to do) for 40 years before electing another king. The author then adds that some people still hope that Arthur did not die and would return as he had promised, and tells of a legend according to which he has been seen since out hunting in the forests.

Morgan features as an immortal ruler of a fantastic Avalon, sometimes alongside the still-alive Arthur, in some subsequent and otherwise non-Arthurian chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of high medieval and early modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalri ...

s such as ''Tirant lo Blanch

''Tirant lo Blanch'' (; modern spelling: ''Tirant lo Blanc''), in English ''Tirant the White'', is a chivalric romance written by the Valencian knight Joanot Martorell, finished posthumously by his friend Martí Joan de Galba and published in ...

'', as well as the tales of Huon of Bordeaux

Huon of Bordeaux is the title character of a 13th-century French epic poem with romance elements.

''Huon of Bordeaux''

The poem tells of Huon, a knight who unwittingly kills Charlot, the son of Emperor Charlemagne. He is given a reprieve from ...

, where the faery king Oberon

Oberon () is a king of the fairy, fairies in Middle Ages, medieval and Renaissance literature. He is best known as a character in William Shakespeare's play ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', in which he is King of the Fairies and spouse of Titania ...

is a son of either Morgan by name or "the Lady of the Secret Isle", and the legend of Ogier the Dane

Ogier the Dane (; ) is a legendary paladin of Charlemagne who appears in many Old French ''chanson de geste, chansons de geste''. In particular, he features as the protagonist in ''La Chevalerie Ogier'' (), which belongs to the ''Geste de Doon de ...

, where Avalon can be described as an enchanted fairy castle (''chasteu d'Auallon''), as it is also in ''Floriant et Florete''. In his ''La Faula'', Guillem de Torroella claims to have visited the Enchanted Island (''Illa Encantada'') and met Arthur who has been brought back to life by Morgan and they both of them are now forever young, sustained by the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail (, , , ) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenanc ...

. In ''La Bataille Loquifer'', Morgan and her sister Marsion bring the hero Renoart to Avalon, where Arthur now prepares his return alongside Morgan, Gawain

Gawain ( ), also known in many other forms and spellings, is a character in Matter of Britain, Arthurian legend, in which he is King Arthur's nephew and one of the premier Knights of the Round Table. The prototype of Gawain is mentioned und ...

, Ywain

In Arthurian legend, Ywain , also known as Yvain and Owain among other spellings (''Ewaine'', ''Ivain'', ''Ivan'', ''Iwain'', ''Iwein'', ''Uwain'', ''Uwaine'', ''Ywan'', etc.), is a Knight of the Round Table. Tradition often portrays him as t ...

, Perceval and Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; ; , ), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First mentioned in literature in the early 12th cen ...

. Such stories, which also include ''Lion de Bourges'', ''Mabrien'', ''Tristan de Nanteuil'', and others, typically take place centuries after the times of King Arthur. According to William W. Kibler,

Erec and Enide

''Erec and Enide'' () is the first of Chrétien de Troyes' five romance poems, completed around 1170. It is one of three completed works by the author. ''Erec and Enide'' tells the story of the marriage of the titular characters, as well as the ...

'', an early Arthurian romance by Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (; ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on King Arthur, Arthurian subjects such as Gawain, Lancelot, Perceval and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's chivalric romances, including ''Erec and Enide'' ...

, mentions at the wedding of Arthur and Guinevere a "friend" (i.e. lover) of Morgan as the Lord of the Isle of Avalon, Guingomar (manuscript variants ''Guinguemar'', ''Guingamar'', ''Guigomar'', ''Guilemer'', ''Gimoers''). In this appearance, he might have been derived from the fairy king Gwyn ap Nudd

Gwyn ap Nudd (, sometimes found with the antiquated spelling Gwynn ap Nudd) is a Welsh mythological figure, the king of the '' Tylwyth Teg'' or " fair folk" and ruler of the Welsh Otherworld, Annwn, and whose name means “Gwyn, son of Nudd”. D ...

, who in the Welsh Arthurian tradition figures as the ruler of Avalon-like Celtic Otherworld

In Celtic mythology, the Otherworld is the realm of the Celtic deities, deities and possibly also the dead. In Gaels, Gaelic and Celtic Britons, Brittonic myth it is usually a supernatural realm of everlasting youth, beauty, health, abundance an ...

, Annwn

Annwn, Annwfn, or Annwfyn (; ''Annwvn'', ''Annwyn'', ''Annwyfn'', ''Annwvyn'', or ''Annwfyn'') is the Otherworld in Welsh mythology. Ruled by Arawn (or, in Arthurian literature, by Gwyn ap Nudd), it is a world of delights and eternal youth wh ...

. The German ''Diu Crône

''Diu Crône'' () is a Middle High German poem of about 30,000 lines treating of King Arthur and the Matter of Britain, dating from around the 1220s and attributed to the epic poet Heinrich von dem Türlin. Little is known of the author thoug ...

'' says the Queen of Avalon is the goddess (''göttin'') Enfeidas, Arthur's aunt (sister of Uther Pendragon

Uther Pendragon ( ; the Brittonic languages, Brittonic name; , or ), also known as King Uther (or Uter), was a List of legendary kings of Britain, legendary King of the Britons and father of King Arthur.

A few minor references to Uther appe ...

) and one of the guardians of the Grail. In Gottfried von Strassburg

Gottfried von Strassburg (died c. 1210) is the author of the Middle High German courtly romance ''Tristan'', an adaptation of the 12th-century ''Tristan and Iseult'' legend. Gottfried's work is regarded, alongside the '' Nibelungenlied'' and Wol ...

's ''Tristan'', Petitcrieu

Petitcrieu, alternatively spelled Petitcreiu, Petitcru, or Pticru, is a legendary magical dog from Arthurian legend present in the chivalric romance of Tristan and Iseult.

In Arthurian legend

In Gottfried von Strassburg's ''Tristan'', Petitcrieu ...

is a magical dog created by a goddess in Avalon. The Venician ''Les Prophéties de Merlin'' features the character of an enchantress known only as the Lady of Avalon (''Dame d'Avalon''), a Merlin's apprentice who is a fierce rival of Morgan as well as of Sebile

Sebile, alternatively written as Sedile, Sebille, Sibilla, Sibyl, Sybilla, and other similar names, is a mythical medieval queen or princess who is frequently portrayed as a fairy or an enchantress in the Arthurian legend and Italian folklore. S ...

, another of Merlin's female students. In the late Italian '' Tavola Ritonda'', the lady of the island of Avalon (''dama dell'isola di Vallone'', likely the same as the Lady of Avalon from the ''Propheties'') is a fairy mother of the evil sorceress Elergia. An unnamed Lady of the Isle of Avalon (named as Lady Lyle of Avalon by Malory) appears indirectly in the Vulgate Cycle story of Sir Balin

Balin the Savage, also known as the Knight with the Two Swords, is a character in Arthurian legend. He is a relatively late addition to the medieval Arthurian world. His story, as told by Thomas Malory in ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', is based upon t ...

in which her damsel brings a cursed magic sword to Camelot

Camelot is a legendary castle and Royal court, court associated with King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described ...

. The tales of the half-fairy Melusine

Mélusine () or Melusine or Melusina is a figure of European folklore, a nixie (folklore), female spirit of fresh water in a holy well or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a Serpent symbolism, serpent or Fish in culture, fish fr ...

have her grow up in the isle of Avalon.

Avalon has been also occasionally described as a valley. In ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', for instance, Avalon is called an isle twice and a vale once (the latter in the scene of Arthur's final voyage, oddly despite Malory's adoption of the boat travel motif). Notably, the vale of Avalon (''vaus d'Avaron'') is mentioned twice in Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron (also spelled in the manuscripts "Roberz", "Borron", "Bouron", "Beron") was a French poet active around the late 12th and early 13th centuries, notable as the reputed author of the poems and ''Merlin''. Although little is known of ...

's Arthurian prequel as a place located in western Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

, to where a fellowship of early Christians started by Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea () is a Biblical figure who assumed responsibility for the burial of Jesus after Crucifixion of Jesus, his crucifixion. Three of the four Biblical Canon, canonical Gospels identify him as a member of the Sanhedrin, while the ...

brought the Grail after its long journey from the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

, finally delivered there by Bron, the first Fisher King

The Fisher King (; ; ; ) is a figure in Arthurian legend, the last in a long line of British kings tasked with guarding the Holy Grail. The Fisher King is both the protector and physical embodiment of his lands, but a wound renders him impoten ...

.

Escavalon

In his final romance, ''

In his final romance, ''Perceval, the Story of the Grail

''Perceval, the Story of the Grail'' () is an unfinished verse romance written by Chrétien de Troyes in Old French in the late 12th century. Later authors added 54,000 more lines to the original 9,000 in what is known collectively as the ''Four ...

'', Chrétien de Troyes featured the sea fortress of Escavalon, ruled by the unspecified King of Escavalon. The name Escavalon might be simply a corruption of the word Avalon that can be literally translated as "Water-Avalon", albeit some scholars proposed various other developments of the name Escavalon from that of Avalon (with Roger Sherman Loomis

Roger Sherman Loomis (1887–1966) was an American scholar and one of the foremost authorities on medieval and Arthurian literature. Loomis is perhaps best known for showing the roots of Arthurian legend, in particular the Holy Grail, in native C ...

noting the similarity of the evolution of Geoffrey's Caliburn into the Chrétien's Escalibur in the case of Excalibur), perhaps in connection with the Old French words for either Slav or Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

. Chretien's Escavalon was renamed as Askalon in ''Parzival

''Parzival'' () is a medieval chivalric romance by the poet and knight Wolfram von Eschenbach in Middle High German. The poem, commonly dated to the first quarter of the 13th century, centers on the Arthurian hero Parzival (Percival in English) ...

'' by Wolfram von Eschenbach

Wolfram von Eschenbach (; – ) was a German knight, poet and composer, regarded as one of the greatest epic poets of medieval German literature. As a Minnesinger, he also wrote lyric poetry.

Life

Little is known of Wolfram's life. Ther ...

, who might have been either confused or inspired by the real-life Middle Eastern coastal city of Ascalon

Ascalon or Ashkelon was an ancient Near East port city on the Mediterranean coast of the southern Levant of high historical and archaeological significance. Its remains are located in the archaeological site of Tel Ashkelon, within the city limi ...

.

It is possible that the Chrétien-era Escavalon has turned or split into the Grail realm of Escalot in later prose romances. Nevertheless, the kingdoms of Escalot and Escavalon both appear concurrently in the Vulgate Cycle. There, Escavalon is ruled by King Alain, whose daughter Florée is rescued by Gawain and later gives birth to his son Guinglain

''Libeaus Desconus'', vv. 7, 13 , "Begete he was of Sir Gawain" v. 8; cf. , p. 226 or (, ,Guingla(i)n, ''Le Bel Inconnu'' v. 3233 et passim, cf. index, p. 409. , , etc.), also known as , or The Fair Unknown, is a character from Arthurian le ...

(and possibly two others). The character of Alain may have been derived from Afallach (Avallach) of Avalon.

Connection to Glastonbury

Though no longer an island in the 12th century, the high conical bulk ofGlastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor is a hill near Glastonbury in the English county of Somerset, topped by the roofless tower of St Michael's Church, a Grade I Listed building (United Kingdom), listed building. The site is managed by the National Trust and has be ...

in today's South-West England. Today, it is a rock outcrop in the town of Glastonbury

Glastonbury ( , ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonbury is less than across the River ...

, situated about 15 miles (25 kilometres) from the sea, but had been surrounded by marsh before the draining of fen

A fen is a type of peat-accumulating wetland fed by mineral-rich ground or surface water. It is one of the main types of wetland along with marshes, swamps, and bogs. Bogs and fens, both peat-forming ecosystems, are also known as mires ...

land in the Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels are a coastal plain and wetland area of Somerset, England, running south from the Mendips to the Blackdown Hills.

The Somerset Levels have an area of about and are bisected by the Polden Hills; the areas to the south ...

. In ancient times, Ponter's Ball Dyke

Ponter's Ball Dyke is a linear earthwork located near Glastonbury in Somerset, England. It crosses, at right angles, an ancient road that continues on to the former island of dry land in the Somerset levels surrounding Glastonbury Tor. It consis ...

would have guarded the only entrance to the island. The Romans eventually built another road to the island. Glastonbury's earliest name in Welsh was the Isle of Glass, which suggests that the location was at one point seen as an island. At the end of the 12th century, Gerald of Wales wrote in ''De instructione principis

(''Instruction for a Ruler'') is a Latin work by Gerald of Wales. It is divided into three "Distinctions". The first contains moral precepts and reflections; the second and third deal with the history of the later 12th century, with a focus on the ...

'':

Around 1190, monks at

Around 1190, monks at Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Its ruins, a grade I listed building and scheduled ancient monument, are open as a visitor attraction.

The abbey was founded in the 8th century and enlarged in the 10th. It wa ...

claimed to have discovered the bones of Arthur and his wife Guinevere. The discovery of the burial is described by chroniclers, notably Gerald, as being just after King Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

's reign when the new abbot of Glastonbury, Henry de Sully, commissioned a search of the abbey grounds. At a depth of 5 m (16 feet), the monks were said to have discovered an unmarked tomb with a massive treetrunk coffin

A treetrunk coffin is a coffin hollowed out of a single massive log. Such coffins have been used for burials since prehistoric times over a wide geographic range, including in Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia.

History

Treetrunk coffins wer ...

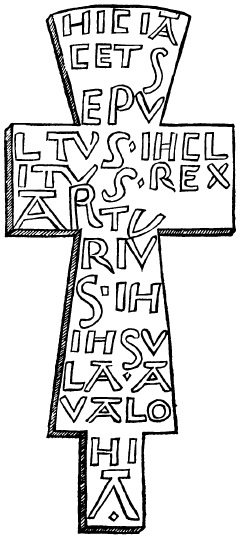

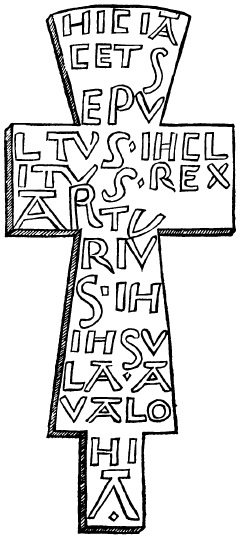

and, also buried, a lead cross bearing the inscription:

Accounts of the exact inscription vary, with five different versions existing. One popular today, made famous by Malory, claims "Here lies Arthur, the king that was and the king that shall be" (''Hic iacet Arthurus, rex quondam rexque futurus''), also known in the now-popular variant "the once and future king" (''rex quondam et futurus''). The earliest is by Gerald in ''Liber de Principis instructione'' c. 1193, who wrote that he viewed the cross in person and traced the lettering. His transcript reads: "Here lies buried the famous ''Arthurus'' with ''Wenneveria'' his second wife in the isle of Avalon" (''Hic jacet sepultus inclitus rex Arthurus cum Wenneveria uxore sua secunda in insula Avallonia''). He wrote that in the coffin were two bodies, whom Giraldus refers to as Arthur and "his queen"; the male body's bones were described as gigantic. The account of the burial by the chronicle of Margam Abbey

Margam Abbey () was a Cistercian monastery, located in the village of Margam, a suburb of modern Port Talbot in Wales.

History

The abbey was founded in 1147 as a daughter house of Clairvaux by Robert, Earl of Gloucester, and was dedicated to ...

says three bodies were found, the other being that of Mordred

Mordred or Modred ( or ; Welsh: ''Medraut'' or ''Medrawt'') is a major figure in the legend of King Arthur. The earliest known mention of a possibly historical Medraut is in the Welsh chronicle ''Annales Cambriae'', wherein he and Arthur are a ...

; Richard Barber

Richard William Barber (born 30 October 1941) is a British historian who has published several books about medieval history and literature. His book ''The Knight and Chivalry'', about the interplay between history and literature, won the Somer ...

argues that Mordred's name was airbrushed out of the story once his reputation as a traitor was appreciated.

The story is today seen as an example of pseudoarchaeology

Pseudoarchaeology (sometimes called fringe or alternative archaeology) consists of attempts to study, interpret, or teach about the subject-matter of archaeology while rejecting, ignoring, or misunderstanding the accepted Scientific method, data ...

. Historians generally dismiss the find's authenticity, attributing it to a publicity stunt performed to raise funds to rebuild the Abbey after it had been destroyed by a 1184 fire. Leslie Alcock

Leslie Alcock (24 April 1925 – 6 June 2006) was Professor of Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, and one of the leading archaeologists of Early Medieval Britain. His major excavations included Dinas Powys hill fort in Wales, Cadbury Ca ...

in his ''Arthur's Britain'' postulated a theory according to which the grave site had been originally discovered in an ancient mausoleum sometime after 945 by Dunstan

Dunstan ( – 19 May 988), was an English bishop and Benedictine monk. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised. His work restored monastic life in En ...

, the Abbot of Glastonbury, who reburied it along with the 10th-century stone cross; it would then become forgotten again until its rediscovery in 1190.

In 1278, the remains were reburied with great ceremony, attended by King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

and Queen Eleanor of Castile

Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 28 November 1290) was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I. She was educated at the Castilian court and also ruled as Countess of Ponthieu in her own right () from 1279. After diplomatic efforts to s ...

, before the High Altar at Glastonbury Abbey. They were moved again in 1368 when the choir

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

was extended. The site became the focus of pilgrimages until the dissolution of the abbey in 1539. The fact that the search for the body is connected to Henry II and Edward I, both kings who fought major Anglo-Welsh wars, has had scholars suggest that propaganda may have played a part as well. Gerald was a constant supporter of royal authority; in his account of the discovery aims to quash the idea of the possibility of King Arthur's messianic return

King Arthur's messianic return is a mythological motif in the legend of King Arthur, which claims that he will one day return in the role of a messiah to save his people. It is an example of the king asleep in mountain motif. King Arthur was a ...

:

The burial discovery ensured that in later romances, histories based on them and in the popular imagination, Glastonbury became increasingly identified with Avalon, an identification that continues strongly today. The later development of the legends of the Holy Grail and Joseph of Arimathea interconnected these legends with Glastonbury and with Avalon, an identification which also seems to be made in ''Perlesvaus''. The popularity of Arthurian romances has meant this area of the Somerset Levels has today become popularly described as the Vale of Avalon.

Modern writers such as

The burial discovery ensured that in later romances, histories based on them and in the popular imagination, Glastonbury became increasingly identified with Avalon, an identification that continues strongly today. The later development of the legends of the Holy Grail and Joseph of Arimathea interconnected these legends with Glastonbury and with Avalon, an identification which also seems to be made in ''Perlesvaus''. The popularity of Arthurian romances has meant this area of the Somerset Levels has today become popularly described as the Vale of Avalon.

Modern writers such as Dion Fortune

Dion Fortune (born Violet Mary Firth, 6 December 1890 – 6 or 8 January 1946) was a British occultist, ceremonial magician, and writer. She was a co-founder of the Fraternity of the Inner Light, an occult organisation that promoted philoso ...

, John Michell

John Michell (; 25 December 1724 – 21 April 1793) was an English natural philosopher and clergyman who provided pioneering insights into a wide range of scientific fields including astronomy, geology, optics, and gravitation. Considered "on ...

, Nicholas Mann and Geoffrey Ashe

Geoffrey Thomas Leslie Ashe (29 March 1923 – 30 January 2022) was a British cultural historian and lecturer, known for his focus on King Arthur.

Early life

Born in London, Ashe was an only child who excelled all his classmates in academics ...

have formed theories based on perceived links between Glastonbury and Celtic legends of the Otherworld in attempts to link the location firmly with Avalon, drawing on the various legends based on Glastonbury Tor as well as drawing on ideas like Earth mysteries

Earth mysteries are a wide range of spiritual, religious ideas focusing on cultural and religious beliefs about the Earth, generally with a regard for specific geographic locations of historic importance. Similar to modern druidry, prehistoric ...

, ley lines

Ley lines () are straight alignments drawn between various historic structures, prehistoric sites and prominent landmarks. The idea was developed in early 20th-century Europe, with ley line believers arguing that these alignments were recognis ...

and even the myth of Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

. Arthurian literature also continues to use Glastonbury as an important location as in ''The Mists of Avalon

''The Mists of Avalon'' is a 1983 historical fantasy novel by American writer Marion Zimmer Bradley, in which the author relates the Arthurian legends from the perspective of the female characters. The book follows the trajectory of Morgaine ...

'', ''A Glastonbury Romance

''A Glastonbury Romance'' was written by John Cowper Powys (1873–1963) in rural upstate New York (state), New York and first published by Simon and Schuster in New York City in March 1932. An English edition published by John Lane (publis ...

'', and '' The Bones of Avalon''. Even the fact that Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

has many apple orchards has been drawn in to support the connection."Glastonbury: Alternative Histories", in Ronald Hutton, ''Witches, Druids and King Arthur''. Glastonbury's reputation as the real Avalon has made it a popular site of tourism. Having become one of the major New Age communities

New Age communities are places where, intentionally or accidentally, communities have grown up to include significant numbers of people with New Age beliefs. An intentional community may have specific aims but are varied and have a variety of str ...

in Europe, the area has great religious significance for neo-Pagans and modern Druids

Druidry, sometimes termed Druidism, is a modern spiritual or religious movement that promotes the cultivation of honorable relationships with the physical landscapes, flora, fauna, and diverse peoples of the world, as well as with nature de ...

, as well as some Christians. Identification of Glastonbury with Avalon within hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture of the mid-1960s to early 1970s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States and spread to dif ...

subculture, as seen in the work of Michell and in the Gandalf's Garden

Gandalf's Garden was a mystical community which flourished at the end of the 1960s as part of the London hippie-underground movement, and ran a shop as well as a magazine of the same name. It emphasised the mystical interests of the period and adv ...

community, also helped inspire the annual Glastonbury Festival

The Glastonbury Festival of Contemporary Performing Arts (commonly referred to as simply Glastonbury Festival, known colloquially as Glasto) is a five-day festival of contemporary performing arts held near Pilton, Somerset, England, in most su ...

.

Sicily and other locations

Medieval settings for the location of Avalon ranged far beyond Glastonbury. Besides the mentioned examples of Gwynedd and Brasil, they included paradisalunderworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

realms equated with the other side of the Earth at the antipodes

In geography, the antipode () of any spot on Earth is the point on Earth's surface diametrically opposite to it. A pair of points ''antipodal'' () to each other are situated such that a straight line connecting the two would pass through Ea ...

. Italian romances and folklore explicitly link Morgan's and sometimes Arthur's eternal domain with Mount Etna

Mount Etna, or simply Etna ( or ; , or ; ; or ), is an active stratovolcano on the east coast of Sicily, Italy, in the Metropolitan City of Catania, between the cities of Messina, Italy, Messina and Catania. It is located above the Conve ...

(Mongibel) in Sicily, and the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina (; ) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria (Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north with the Ionian Sea to the south, with ...

, located to the north of Etna and associated with the optical mirage phenomenon of Fata Morgana ("Morgan the Fairy").Avalon in Norris J. Lacy, Editor, ''The Arthurian Encyclopedia'' (1986 Peter Bedrick Books, New York). Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest known Roman geographer. He was born at the end of the 1st century BC in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nea ...

's ancient Roman description of the island of Île de Sein

The Île de Sein is a Breton island in the Atlantic Ocean, off Finistère, eight kilometres from the Pointe du Raz (''raz'' meaning "water current"), from which it is separated by the Raz de Sein. Its Breton name is ''Enez-Sun''. The islan ...

, off the coast of Brittany, was also notably one of Geoffrey of Monmouth's original inspirations for his Avalon.

In modern times, similar to the search for Arthur's mythical capital Camelot, a variety of sites across Britain, France and elsewhere have been put forward as being the "real Avalon". Such proposed locations include

In modern times, similar to the search for Arthur's mythical capital Camelot, a variety of sites across Britain, France and elsewhere have been put forward as being the "real Avalon". Such proposed locations include Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

or other places in or across the Atlantic, the former Roman fort of Aballava

Aballava or Aballaba (with the modern name of Burgh by Sands) was a Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall, between Petriana ( Stanwix) to the east and Coggabata ( Drumburgh) to the west. It is about one and a half miles south of the Solway Firth, and ...

(known as Avalana by the sixth century) in Cumbria, Bardsey Island

Bardsey Island (), known as the legendary "Island of 20,000 Saints", is located off the Llŷn Peninsula in the Wales, Welsh county of Gwynedd. The Welsh language, Welsh name means "The Island in the Currents", while its English name refers to t ...

off the coast of Gwynedd, the isle of Île Aval

The Isle of Aval, known as Enez-Aval in Breton and Ile d'Aval in French, is an island in Brittany, situated east of Île-Grande, in the commune of Pleumeur-Bodou and the wider Canton of Tréguier.

History

The charm of the island of Aval with i ...

on the coast of Brittany, and Lady's Island in Ireland's Leinster. In the works of William F. Warren, Avalon was compared to Hyperborea

In Greek mythology, the Hyperboreans (, ; ) were a mythical people who lived in the far northern part of the Ecumene, known world. Their name appears to derive from the Greek , "beyond Boreas (god), Boreas" (the God of the north wind). Some schol ...

along with the Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

and theorized to be located in the Arctic. Geoffrey Ashe championed an association of Avalon with the town of Avallon

Avallon () is a commune in the Burgundian department of Yonne, in France.

Name

Avallon, Latin ''Aballō'', ablative ''Aballone'', is ultimately derived from Gaulish ''*Aballū'', oblique ''*Aballon-'' meaning "Apple-tree (place)" or "(plac ...

in Burgundy, as part of a theory connecting King Arthur to the Romano-British

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, ...

leader Riothamus

(also spelled or ) was a Romano-British military leader, who was active circa AD 470. He fought against the Goths in alliance with the declining Western Roman Empire. He is called "King of the Britons" by the 6th-century historian Jordanes, but t ...

who was last seen in that area. Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was an English poet, soldier, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were b ...

identified Avalon with the Spanish island of Majorca (Mallorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest of the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, seventh largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.

The capital of the island, Palma, Majorca, Palma, i ...

), while Laurence Gardner suggested the Isle of Arran

The Isle of Arran (; ) or simply Arran is an island off the west coast of Scotland. It is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde and the seventh-largest Scottish island, at . Counties of Scotland, Historically part of Buteshire, it is in the ...

off the coast of Scotland. Graham Phillips claimed to have located the grave of the "historical Arthur" ( Owain Ddantgwyn) in the "true site of Avalon" on a former island at Baschurch

Baschurch is a village and civil parish in Shropshire, England. It lies in the north of Shropshire. The village had a population of 2,503 as of the 2011 census. Shrewsbury is to the south-east, Oswestry is to the north-west, and Wem is to the n ...

in Shropshire.

See also

*Avalon

Avalon () is an island featured in the Arthurian legend. It first appeared in Geoffrey of Monmouth's 1136 ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' as a place of magic where King Arthur's sword Excalibur was made and later where Arthur was taken to recove ...

– city in Santa Catalina Island (California)

Santa Catalina Island (; ) often shortened to Catalina Island or Catalina, is a rocky island, part of the Channel Islands (California), Channel Islands, off the coast of Southern California in the Gulf of Santa Catalina. The island covers an ...

* Brittia

Brittia (), according to Procopius, was an island known to the inhabitants of the Low Countries under Frankish rule (viz. the North Sea coast of Austrasia), corresponding both to a real island used for burial and a mythological Isle of the Bless ...

* Tír na nÓg

In Irish mythology, Tír na nÓg ( , ; ) or Tír na hÓige ('Land of Youth') is one of the names for the Celtic Otherworld, or perhaps for a part of it. Tír na nÓg is best known from the tale of Oisín ("''uh''-''sheen''") and Niamh ("''neev ...

Notes

References

;Citations ;Bibliography * * * * * * * *External links

*Avalon

at The Camelot Project {{Authority control Fiction about immortality Fictional populated places Fictional valleys Glastonbury Joseph of Arimathea Locations associated with Arthurian legend Places in Celtic mythology Mythological islands