August Hoch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

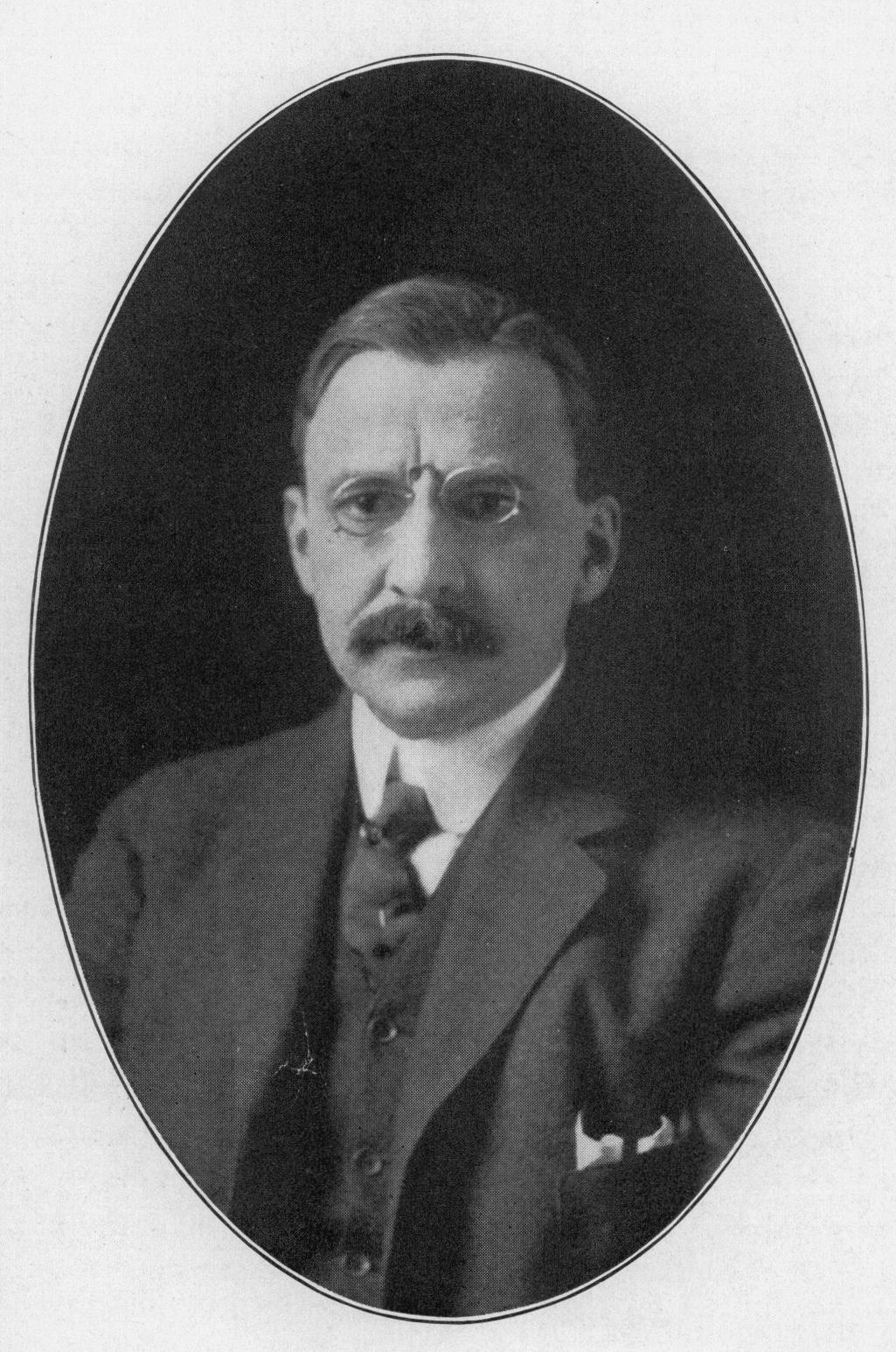

August Hoch (20 April 1868 – 23 September 1919) was a Swiss–American psychiatrist who was the third director of the

August Hoch (20 April 1868 – 23 September 1919) was a Swiss–American psychiatrist who was the third director of the

New York State Psychiatric Institute

The New York State Psychiatric Institute, located at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, was established in 1895 as one of the first institutions in the United States ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

from 1 February 1910 to 1 October 1917. As a neuropathologist

Neuropathology is the study of disease of nervous system tissue, usually in the form of either small surgical biopsies or whole-body autopsies. Neuropathologists usually work in a department of anatomic pathology, but work closely with the cli ...

and clinician

A clinician is a health care professional typically employed at a skilled nursing facility or clinic. Clinicians work directly with patients rather than in a laboratory, community health setting or in research. A clinician may diagnose, treat a ...

, he exerted his influence on psychiatric

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, mood, emotion, and behavior.

Initial psychiatric assessment of ...

developments during the early 20th century in the United States.

Biography

He was born Charles August Hoch (and would sign legal documents with his full name) inBasel, Switzerland

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's third-most-populous city (after Zurich and Geneva), with ...

, the son of a minister, who was also director of the Basel University Hospital. Arriving in Baltimore on the passenger shoip "Rhein" on 3 August 1886 at the age of 19, he emigrated to the United States to pursue his medical education. He spent two years at the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

, where he was influenced by Dr. William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first Residency (medicine), residency program for speci ...

. When, in 1889, Osler moved to Johns Hopkins University Hospital

Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1889, Johns Hopkins Hospital and its school of medicine are considered to be the foundin ...

in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the List of United States ...

, Hoch followed to work at the Johns Hopkins outpatient

A patient is any recipient of health care services that are performed by healthcare professionals. The patient is most often ill or injured and in need of treatment by a physician, nurse, optometrist, dentist, veterinarian, or other healt ...

neurological

Neurology (from , "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the nervous system, which comprises the brain, the s ...

clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambulatory care clinic) is a health facility that is primarily focused on the care of outpatients. Clinics can be privately operated or publicly managed and funded. They typically cover the primary care needs ...

and to pursue medical training at the University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the Univ ...

. He received his M.D. degree from the University of Maryland in 1890. He remained an assistant to Osler in the clinic.

In October 1893, Hoch assumed a position at the McLean Asylum in Somerville, Massachusetts, near Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, to develop the pathological

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

and psychological

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

laboratories

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which science, scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratories are found in a variety of settings such as s ...

and the clinical psychiatric programs. Before assuming his position at McLean, McLean's director Edward Cowles sent him to Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

for most of 1893 and 1894 study in several European laboratories, including those of Friedrich von Recklinghausen, a pathologist

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

at the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

; Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and biology, was t ...

, a psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and explanation, interpretatio ...

at the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

; and Emil Kraepelin

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin (; ; 15 February 1856 – 7 October 1926) was a German psychiatrist. H. J. Eysenck's Encyclopedia of Psychology identifies him as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology and psychiatric ...

, a psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry. Psychiatrists are physicians who evaluate patients to determine whether their symptoms are the result of a physical illness, a combination of physical and mental ailments or strictly ...

at the University of Heidelberg

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg (; ), is a public university, public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Founded in 1386 on instruction of Pope Urban VI, Heidelberg is List ...

. He would return to European laboratories and Kraepelin's clinic in Heidelberg, Germany, in 1897.

In July 1894 he married Emmy Muench (22 January 1862 – 27 August 1941) of Basel, Switzerland, during his European trip. Hoch returned to America with his new bride on the "Veendam" passenger ship, arriving in New York City on 12 November 1894. In May 1895, while working at the newly named McLean Hospital, now on a new campus in Waverly (Belmont), Massachusetts, the Hoch's only child Susan (Susie) Hoch (21 May 1895 – 8 March 1980) was born. In Queens, New York City, on 3 July 1921 Susan married Lawrence S. Kubie (1896–1973), who would go on to become a noted psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. They produced two children and divorced in 1935. Susan would go on to study psychoanalysis in Europe, was a lifelong acquaintance of Anna Freud

Anna Freud CBE ( ; ; 3 December 1895 – 9 October 1982) was a British psychoanalyst of Austrian Jewish descent. She was born in Vienna, the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She followed the path of her father a ...

, and in 1943 helped found the William Hodson Community Center in the Bronx which was the first experimental psychiatric center for the elderly. She co-authored a book with Gertrude Landrau that would be influential in inspiring the creation of geriatric centers in the US.

Hoch formally left McLean Hospital on 23 June 1905. On 1 July 1905, Hoch began a new position at the Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains, New York

White Plains is a city in and the county seat of Westchester County, New York, United States. It is an inner suburb of New York City, and a commercial hub of Westchester County, a densely populated suburban county that is home to about one milli ...

as its first assistant physician and special clinician. It was there that he became interested in psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

, which he believed would illuminate the field of human conduct. In 1908 he spent time in Zurich at the Burgholzli Mental Hospital with its director, Eugen Bleuler

Paul Eugen Bleuler ( ; ; 30 April 1857 – 15 July 1939) was a Swiss psychiatrist and eugenicist most notable for his influence on modern concepts of mental illness. He coined several psychiatric terms including "schizophrenia", " schizoid", "a ...

, and second-in-command Carl Gustav Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology. A prolific author of over 20 books, illustrator, and correspondent, Jung was a ...

where he deepened his knowledge of psychoanalysis, was trained in the use of the word association experiment, and became familiar with a new disease concept – schizophrenia – which Bleuler had first proposed in a publication that year. After four years at Bloomingdale, in July 1909 he was offered the directorship of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, following Dr. Adolf Meyer (psychiatrist)

Adolf Meyer (September 13, 1866 – March 17, 1950) was a Swiss-born psychiatrist who rose to prominence as the first psychiatrist-in-chief of the Johns Hopkins Hospital (1910–1941). He was president of the American Psychiatric Association in ...

who was moving to the Johns Hopkins University. A major objective was to use the New York State Psychiatric Institute's services as an educational locus for physicians working in the state hospitals

The State Hospital (also known as Carstairs Hospital, or simply Carstairs) is a psychiatric hospital located close to the villages of Carstairs and Carstairs Junction, in South Lanarkshire, Scotland. It provides care and treatment in conditions ...

.

While at Bloomingdale, in 1909 Hoch put in his application to become a naturalized U.S. citizen, and it was granted in August 1911 when he resided in New York.

Hoch was actively involved in psychiatric organizations. He was president of the New York Psychiatric Society in 1908 and in 1909; president of the American Psychopathological Society in 1913; and president of the American Psychoanalytic Association

The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsA) is an association of psychoanalysts in the United States. APsA serves as a scientific and professional organization with a focus on education, research, and membership development.

APsA comprises 34 ...

in 1913 and in 1914. He was a member of the American Neurological Society, the American Medico-Psychological Society (now the American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychiatrists and trainee psychiatrists in the United States, and the largest psychiatric organization in the world. It has more than 39,200 members who are in ...

), and the New York Neurological Society. He was a leader in planning a scientific psychiatric journal by the Institute titled ''Psychiatric Bulletin''.

Legacy

In 6 March 1913, Hoch introduced Eugen Bleuler's disease concept of schizophrenia to elite American alienists and neurologists for the first time during a meeting of the New York Psychiatrical Society. According to him, "all of them made a lot of fun at the term, but it is remarkable what one can get used to." Hoch wrote most of one book, ''Benign Stupors: A Study of a New Manic-Depressive Reaction Type'', which was published posthumously after an ailing Hoch asked psychiatrist John T. MacCurdy to finish it for him after his death. He retired from the New York State Psychiatric Institute on 1 October 1917 because of ill health and moved to California. He was the live-in psychiatrist for Stanley McCormick at his Riven Rock estate in Santa Barbara. He died on 23 September 1919 ofnephritis

Nephritis is inflammation of the kidneys and may involve the glomeruli, tubules, or interstitial tissue surrounding the glomeruli and tubules. It is one of several different types of nephropathy.

Types

* Glomerulonephritis is inflammation ...

at the University Hospital in San Francisco, California.

References

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hoch, August 1868 births 1919 deaths American psychiatrists Physicians from Basel-Stadt Swiss emigrants to the United States Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania alumni University of Strasbourg alumni Leipzig University alumni Heidelberg University alumni Physicians from New York (state) Deaths from nephritis