Atrocity propaganda on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Atrocity propaganda is the spreading of information about the crimes committed by an enemy, which can be factual, but often includes or features deliberate fabrications or exaggerations. This can involve photographs, videos, illustrations, interviews, and other forms of information presentation or reporting.

The inherently violent nature of war means that exaggeration and invention of atrocities often becomes the main staple of propaganda.

Atrocity propaganda is the spreading of information about the crimes committed by an enemy, which can be factual, but often includes or features deliberate fabrications or exaggerations. This can involve photographs, videos, illustrations, interviews, and other forms of information presentation or reporting.

The inherently violent nature of war means that exaggeration and invention of atrocities often becomes the main staple of propaganda.

In 1782,

In 1782,

Another atrocity story involved a Canadian soldier, who had supposedly been crucified with bayonets by the Germans (see The Crucified Soldier). Many Canadians claimed to have witnessed the event, yet they all provided different version of how it had happened. The Canadian high command investigated the matter, concluding that it was untrue.

Other reports circulated of Belgian women, often nuns, who had their breasts cut off by the Germans. A story about German corpse factories, where bodies of German soldiers were supposedly turned into glycerine for weapons, or food for hogs and poultry, was published in a '' Times'' article on April 17, 1917.Kingsbury (2010), p

Another atrocity story involved a Canadian soldier, who had supposedly been crucified with bayonets by the Germans (see The Crucified Soldier). Many Canadians claimed to have witnessed the event, yet they all provided different version of how it had happened. The Canadian high command investigated the matter, concluding that it was untrue.

Other reports circulated of Belgian women, often nuns, who had their breasts cut off by the Germans. A story about German corpse factories, where bodies of German soldiers were supposedly turned into glycerine for weapons, or food for hogs and poultry, was published in a '' Times'' article on April 17, 1917.Kingsbury (2010), p

49

/ref> In the postwar years, investigations in Britain and France revealed that these stories were false. In 1915, the British government asked Viscount Bryce, one of the best-known contemporary historians, to head the Committee on Alleged German Outrages which was to investigate the allegations of atrocities. The report purported to prove many of the claims, and was widely published in the United States, where it contributed to convince the American public to enter the war. Few at the time criticised the accuracy of the report. After the war, historians who sought to examine the documentation for the report were told that the files had mysteriously disappeared. Surviving correspondence between the members of the committee revealed they actually had severe doubts about the credibility of the tales they investigated.

German newspapers published allegations that Armenians were murdering Muslims in Turkey. Several newspapers reported that 150,000 Muslims had been murdered by Armenians in Van province. An article about the 1908 Revolution (sometimes called the "Turkish national awakening") published by a German paper accused the "Ottomans of the Christian tribe" (meaning the Armenians) of taking up arms after the revolution and killing Muslims.

In 1915, the British government asked Viscount Bryce, one of the best-known contemporary historians, to head the Committee on Alleged German Outrages which was to investigate the allegations of atrocities. The report purported to prove many of the claims, and was widely published in the United States, where it contributed to convince the American public to enter the war. Few at the time criticised the accuracy of the report. After the war, historians who sought to examine the documentation for the report were told that the files had mysteriously disappeared. Surviving correspondence between the members of the committee revealed they actually had severe doubts about the credibility of the tales they investigated.

German newspapers published allegations that Armenians were murdering Muslims in Turkey. Several newspapers reported that 150,000 Muslims had been murdered by Armenians in Van province. An article about the 1908 Revolution (sometimes called the "Turkish national awakening") published by a German paper accused the "Ottomans of the Christian tribe" (meaning the Armenians) of taking up arms after the revolution and killing Muslims.

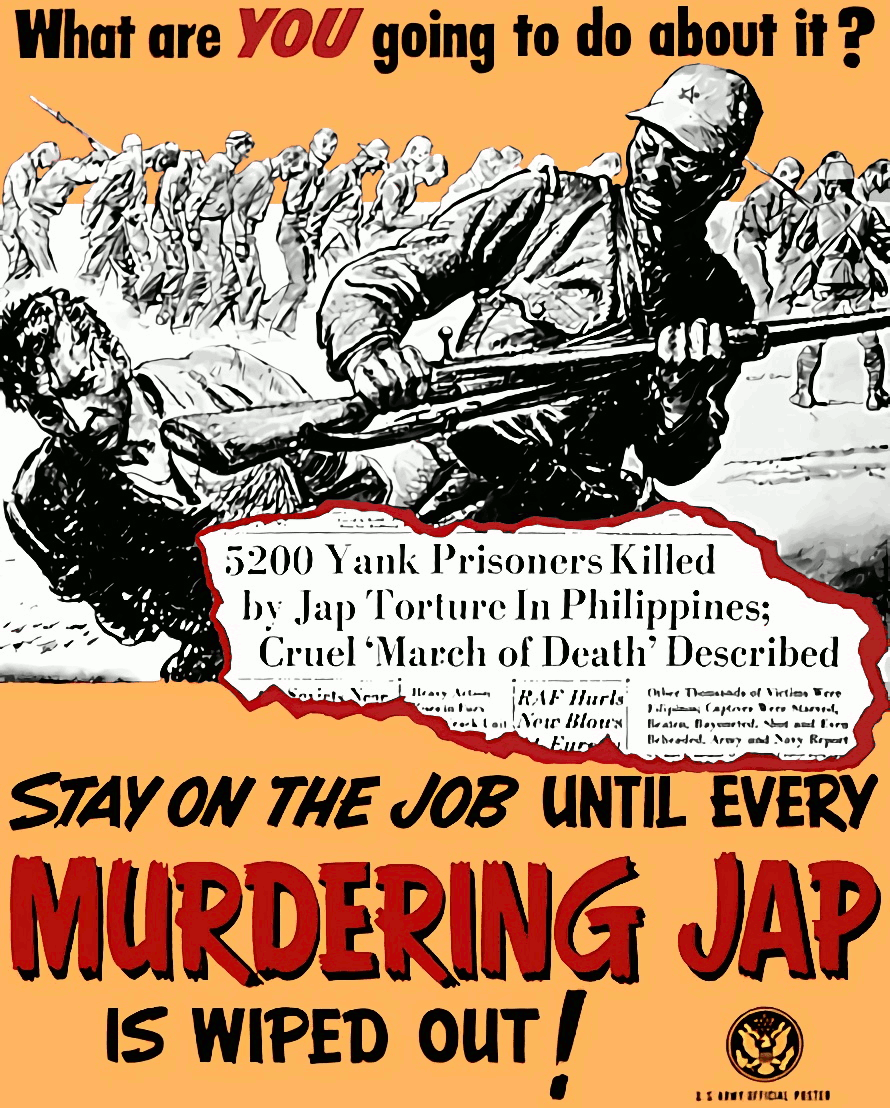

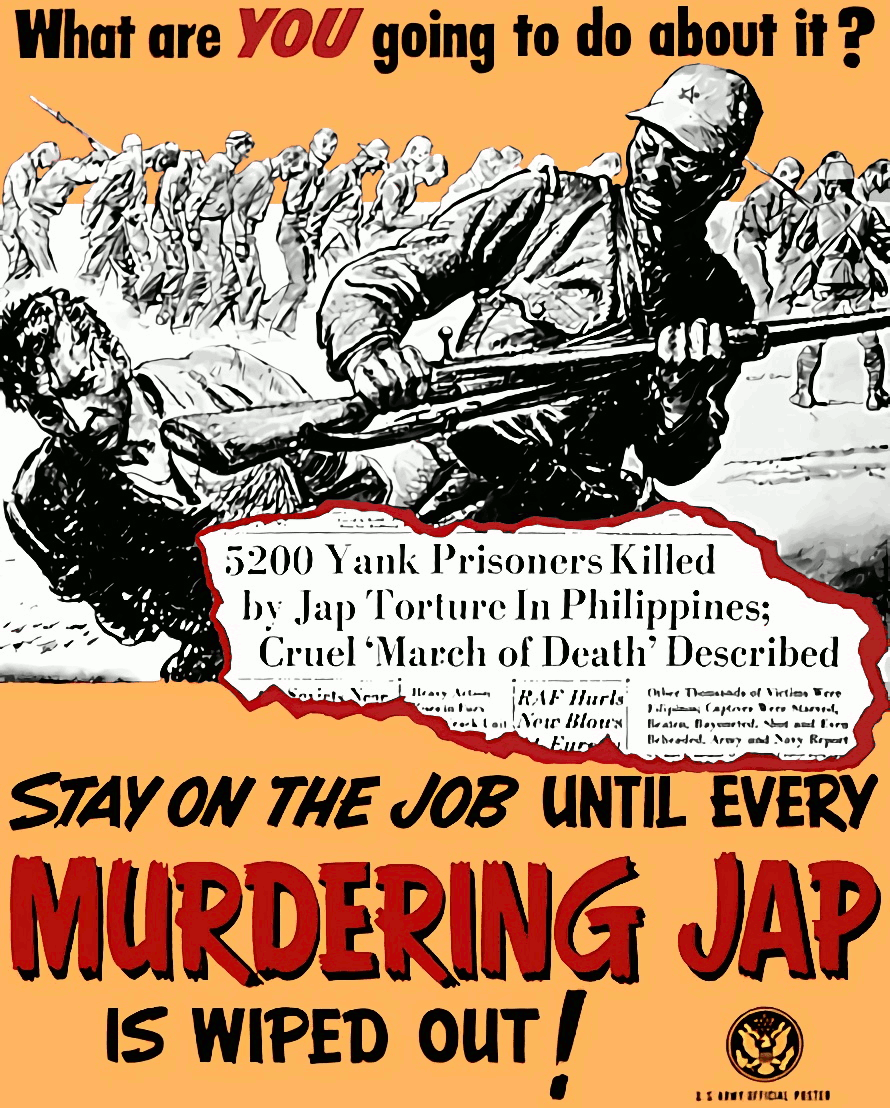

During World War II, atrocity propaganda was not used on the same scale as in World War I, as by then it had long been discredited by its use during the previous conflict. There were exceptions in some propaganda films, such as '' Hitler's Children'', '' Women in Bondage'', and '' Enemy of Women'', which portrayed the Germans (as opposed to just Nazis) as enemies of civilization, abusing women and the innocent. ''Hitler's Children'' is now spoken of as "lurid", while ''Women in Bondage'' is described as a low-budget

During World War II, atrocity propaganda was not used on the same scale as in World War I, as by then it had long been discredited by its use during the previous conflict. There were exceptions in some propaganda films, such as '' Hitler's Children'', '' Women in Bondage'', and '' Enemy of Women'', which portrayed the Germans (as opposed to just Nazis) as enemies of civilization, abusing women and the innocent. ''Hitler's Children'' is now spoken of as "lurid", while ''Women in Bondage'' is described as a low-budget

According to a 1985 UN report backed by Western countries, the KGB had deliberately designed mines to look like toys, and deployed them against Afghan children during the

According to a 1985 UN report backed by Western countries, the KGB had deliberately designed mines to look like toys, and deployed them against Afghan children during the

During the Battle of Jenin, Palestinian officials claimed there was a massacre of civilians in the refugee camp, which was proven false by subsequent international investigations.

During the

During the Battle of Jenin, Palestinian officials claimed there was a massacre of civilians in the refugee camp, which was proven false by subsequent international investigations.

During the

Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition

Oxford University Press, 2019. * Gullace, Nicoletta F. (Sept 2011). "Allied Propaganda and World War I: Interwar Legacies, Media Studies, and the Politics of War Guilt". ''History Compass'' 9#9, pp. 686–700. * Shupe, A.D. and Bromley, D.G. (1981). ''

"Atrocitas/enormitas. Esquisse pour une histoire de la catégorie de 'crime énorme' du Moyen Âge à l'époque moderne"

Clio@Themis, Revue électronique d'histoire du droit, n. 4.

Othering/Atrocity Propaganda

in

1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War

– The Independent

Atrocity propaganda

– The British Library {{Propaganda Journalistic hoaxes Moral panic Black propaganda Psychological warfare techniques Fake news Defamation Information operations and warfare Appeals to emotion Psychological manipulation

Atrocity propaganda is the spreading of information about the crimes committed by an enemy, which can be factual, but often includes or features deliberate fabrications or exaggerations. This can involve photographs, videos, illustrations, interviews, and other forms of information presentation or reporting.

The inherently violent nature of war means that exaggeration and invention of atrocities often becomes the main staple of propaganda.

Atrocity propaganda is the spreading of information about the crimes committed by an enemy, which can be factual, but often includes or features deliberate fabrications or exaggerations. This can involve photographs, videos, illustrations, interviews, and other forms of information presentation or reporting.

The inherently violent nature of war means that exaggeration and invention of atrocities often becomes the main staple of propaganda. Patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

is often not enough to make people hate the enemy, and propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

is also necessary. "So great are the psychological resistances to war in modern nations", wrote Harold Lasswell

Harold Dwight Lasswell (February 13, 1902 – December 18, 1978) was an American political scientist and communications theorist. He earned his bachelor's degree in philosophy and economics and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He was a ...

, "that every war must appear to be a war of defense against a menacing, murderous aggressor. There must be no ambiguity about who the public is to hate." Human testimony may be unreliable even in ordinary circumstances, but in wartime, it can be further muddled by bias, sentiment, and misguided patriotism.

According to Paul Linebarger, atrocity propaganda leads to real atrocities, as it incites the enemy into committing more atrocities, and, by heating up passions, it increases the chances of one's own side committing atrocities, in revenge for the ones reported in propaganda. Atrocity propaganda might also lead the public to mistrust reports of actual atrocities. In January 1944, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler (, ; ; ; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest, and was educated in Austria, apart from his early school years. In 1931, Koestler j ...

wrote of his frustration at trying to communicate what he had witnessed in Nazi-occupied Europe: the legacy of anti-German stories during World War I, many of which were debunked in the postwar years, meant that these reports were received with considerable amounts of skepticism.

Like propaganda, atrocity rumors

A rumor (American English), or rumour (British English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences; derived from Latin 'noise'), is an unverified piece of information circulating among people, especial ...

detailing exaggerated or invented crimes perpetrated by enemies are also circulated to vilify the opposing side. The application of atrocity propaganda is not limited to times of conflict but can be implemented to sway public opinion and create a to declare war.

Techniques

By establishing a baseline lie and painting the enemy as a monster, atrocity propaganda serves as anintelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

function, since it wastes the time and resources of the enemy's counterintelligence

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's Intelligence agency, intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering informati ...

services to defend itself. The propagandists' goal is to influence perceptions, attitudes, opinions, and policies; often targeting officials at all levels of government. Atrocity propaganda is violent, gloomy, and portrays doom to help rile up and get the public excited. It dehumanizes the enemy, making them easier to kill. Wars have become more serious, and less gentlemanly; the enemy must now be taken into account not merely as a man, but as a fanatic. So, "falsehood is a recognized and extremely useful weapon in warfare, and every country uses it quite deliberately to deceive its own people, attract neutrals, and to mislead the enemy." Harold Lasswell saw it as a handy rule for arousing hate, and that "if at first they do not enrage, use an atrocity. It has been employed with unvarying success in every conflict known to man."

The extent and devastation of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

required nations to keep morale high. Propaganda was used here to mobilize hatred against the enemy, convince the population of the justness of one's own cause, enlist the active support and cooperation of neutral countries, and strengthen the support of one's allies. The goal was to make the enemy appear savage, barbaric, and inhumane.

Atrocity propaganda in history

Before the 20th century

In a sermon at Clermont during theCrusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

, Urban II justified the war against Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

by claiming that the enemy "had ravaged the churches of God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

in the Eastern provinces, circumcised Christian men, violated women, and carried out the most unspeakable torture before killing them." Urban II's sermon succeeded in mobilizing popular enthusiasm in support of the People's Crusade.

Lurid tales purporting to unveil Jewish atrocities against Christians were widespread during the Middle Ages. The charge against Jews of kidnapping and murdering Christian children to consume their blood during Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

became known as blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

.

In the 17th century, the English press fabricated graphic descriptions of atrocities allegedly committed by Irish Catholics against English Protestants, including the torture of civilians and the raping of women. The English public reacted to these stories with calls for stern reprisals. During the Irish rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 was an uprising in Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, initiated on 23 October 1641 by Catholic gentry and military officers. Their demands included an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and ...

, lurid reports of atrocities, including of pregnant women who had been ripped open and had their babies pulled out, provided Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

with justification for his subsequent slaughter of defeated Irish rebel and civilians.

In 1782,

In 1782, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

wrote and published an article purporting to reveal a letter between a British agent and the governor of Canada, listing atrocities supposedly perpetrated by Native American allies of Britain against colonists, including detailed accounts of the scalping of women and children. The account was a fabrication, published in the expectation that it would be reprinted by British newspapers and therefore sway British public opinion in favor of peace with the United States.

After the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the form ...

in India, stories began to circulate in the British and colonial press of atrocities, especially rapes of European women, in places like Cawnpore; a subsequent official inquiry found no evidence for any of the claims.

In the lead up to the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, Pulitzer and Hearst published stories of Spanish atrocities against Cubans. While occasionally true, the majority of these stories were fabrications meant to boost sales.

20th century

World War I

Atrocitypropaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

was widespread during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, when it was used by all belligerents, playing a major role in creating the wave of patriotism that characterised the early stages of the war.Cull et al. (2003), p. 25 British propaganda is regarded as having made the most extensive use of fictitious atrocities to promote the war effort.

One such story was that German soldiers were deliberately mutilating Belgian babies by cutting off their hands, in some versions even eating them. Eyewitness accounts told of having seen a similarly mutilated baby. As Arthur Ponsonby later pointed out, in reality a baby would be very unlikely to survive similar wounds without immediate medical attention.

Another atrocity story involved a Canadian soldier, who had supposedly been crucified with bayonets by the Germans (see The Crucified Soldier). Many Canadians claimed to have witnessed the event, yet they all provided different version of how it had happened. The Canadian high command investigated the matter, concluding that it was untrue.

Other reports circulated of Belgian women, often nuns, who had their breasts cut off by the Germans. A story about German corpse factories, where bodies of German soldiers were supposedly turned into glycerine for weapons, or food for hogs and poultry, was published in a '' Times'' article on April 17, 1917.Kingsbury (2010), p

Another atrocity story involved a Canadian soldier, who had supposedly been crucified with bayonets by the Germans (see The Crucified Soldier). Many Canadians claimed to have witnessed the event, yet they all provided different version of how it had happened. The Canadian high command investigated the matter, concluding that it was untrue.

Other reports circulated of Belgian women, often nuns, who had their breasts cut off by the Germans. A story about German corpse factories, where bodies of German soldiers were supposedly turned into glycerine for weapons, or food for hogs and poultry, was published in a '' Times'' article on April 17, 1917.Kingsbury (2010), p49

/ref> In the postwar years, investigations in Britain and France revealed that these stories were false.

In 1915, the British government asked Viscount Bryce, one of the best-known contemporary historians, to head the Committee on Alleged German Outrages which was to investigate the allegations of atrocities. The report purported to prove many of the claims, and was widely published in the United States, where it contributed to convince the American public to enter the war. Few at the time criticised the accuracy of the report. After the war, historians who sought to examine the documentation for the report were told that the files had mysteriously disappeared. Surviving correspondence between the members of the committee revealed they actually had severe doubts about the credibility of the tales they investigated.

German newspapers published allegations that Armenians were murdering Muslims in Turkey. Several newspapers reported that 150,000 Muslims had been murdered by Armenians in Van province. An article about the 1908 Revolution (sometimes called the "Turkish national awakening") published by a German paper accused the "Ottomans of the Christian tribe" (meaning the Armenians) of taking up arms after the revolution and killing Muslims.

In 1915, the British government asked Viscount Bryce, one of the best-known contemporary historians, to head the Committee on Alleged German Outrages which was to investigate the allegations of atrocities. The report purported to prove many of the claims, and was widely published in the United States, where it contributed to convince the American public to enter the war. Few at the time criticised the accuracy of the report. After the war, historians who sought to examine the documentation for the report were told that the files had mysteriously disappeared. Surviving correspondence between the members of the committee revealed they actually had severe doubts about the credibility of the tales they investigated.

German newspapers published allegations that Armenians were murdering Muslims in Turkey. Several newspapers reported that 150,000 Muslims had been murdered by Armenians in Van province. An article about the 1908 Revolution (sometimes called the "Turkish national awakening") published by a German paper accused the "Ottomans of the Christian tribe" (meaning the Armenians) of taking up arms after the revolution and killing Muslims.

World War II

exploitation film

An exploitation film is a film that seeks commercial success by capitalizing on current trends, niche genres, or sensational content. Exploitation films often feature themes such as suggestive or explicit sex, sensational violence, drug use, nudi ...

; the latter carries a disclaimer that "everything in the film is true", but facts are often distorted or sensationalized.

However, the Germans often claimed that largely accurate descriptions of German atrocities were just "atrocity propaganda" and a few Western leaders were thus hesitant to believe early reports of Nazi atrocities, especially the existence of concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

, death camps and the many massacres

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

perpetrated by German troops and SS Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imp ...

during the war. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

and Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

knew from radio intercepts via Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and Bletchley Park estate, estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allies of World War II, Allied World War II cryptography, code-breaking during the S ...

that such massacres were widespread in Poland and other east European territories. Moreover, the existence of concentration camps like Dachau was well known both in Germany and throughout the world as a result of German propaganda itself, as well as many exposures by escapees and others from 1933 onwards. Their discovery towards the end of the war shocked many in the west, especially of Bergen-Belsen

Bergen-Belsen (), or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in Northern Germany, northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen, Lower Saxony, Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, ...

and Dachau by allied soldiers, but the atrocities carried out there were amply supported by the facts on the ground. The Nuremberg trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

in 1945/6 confirmed the extent of genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

, Nazi medical experimentation, massacres

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

and torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

on a very wide scale. Later Nuremberg trials produced abundant evidence of atrocities carried out on prisoners and captives.

The Germans themselves made heavy use of atrocity propaganda, both before the war and during it. Violence between ethnic Germans and the Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, such as the 1939 Bloody Sunday massacre, was characterised as barbaric slaughter of the German population by the subhuman Poles, and used to justify the genocide of the Polish population according to the Nazi . Late in the war, Nazi propaganda used exaggerated depictions of real or planned Allied crimes against Germany, such as the bombing of Dresden, the Nemmersdorf massacre, and the Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan was a proposal to weaken Germany following World War II by eliminating its arms industry and removing or destroying other key industries basic to military strength. This included the removal or destruction of all industria ...

for the deindustrialisation

Deindustrialization is a process of social and economic change caused by the removal or reduction of industrial capacity or activity in a country or region, especially of heavy industry or manufacturing industry.

There are different interpr ...

of Germany to frighten and enrage German civilians into resistance. Hitler's last directive, given fifteen days before his suicide, proclaimed the postwar intentions of the " Jewish Bolsheviks" to be the total genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

of the German people, with the men sent off to labour camps in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and the women and girls made into military sex slaves.

Soviet–Afghan War

According to a 1985 UN report backed by Western countries, the KGB had deliberately designed mines to look like toys, and deployed them against Afghan children during the

According to a 1985 UN report backed by Western countries, the KGB had deliberately designed mines to look like toys, and deployed them against Afghan children during the Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

.

Newspapers such as the ''New York Times'' ran stories denouncing the "ghastly, deliberate crippling of children" and noting that while the stories had been met with skepticism by the public, they had been proven by the "incontrovertible testimony" of a UN official testifying the existence of booby-trap toys in the shape of harmonicas, radios, or birds.

The story likely originated from the PFM-1 mine, which was made from brightly colored plastic and had been indirectly copied from the American BLU-43 Dragontooth design. The Mine Action Coordination Center of Afghanistan reported that the allegations "gained a life for obvious journalist reasons", but otherwise had no basis in reality.

Yugoslav Wars

In November 1991, a Serbian photographer claimed to have seen the corpses of 41 children, which had allegedly been killed by Croatian soldiers. The story was published by media outlets worldwide, but the photographer later admitted to fabricating his account. The story of this atrocity was blamed for inciting a desire for vengeance in Serbian rebels, who summarily executed Croatian fighters who were captured near the alleged crime scene the day after the forged report was published.Gulf War

Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990. On October 10, 1990, a youngKuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

i girl known only as " Nayirah" appeared in front of a congressional committee and testified that she witnessed the mass murdering of infants, when Iraqi soldiers had snatched them out of hospital incubators and threw them on the floor to die. Her testimony became a lead item in newspapers, radio and TV all over the US. The story was eventually exposed as a fabrication in December 1992, in a CBC-TV program called '' To Sell a War''. Nayirah was revealed to be the daughter of Kuwait's ambassador to the United States, and had not actually seen the "atrocities" she described take place; the PR firm Hill & Knowlton, which had been hired by the Kuwaiti government to devise a PR campaign to increase American public support for a war against Iraq, had heavily promoted her testimony.

21st century

Iraq War

In the runup to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, press stories appeared in theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

of a plastic shredder or wood chipper into which Saddam and Qusay Hussein

Qusay Saddam Hussein al-Nasiri al-Tikriti (; 17 May 1966 – 22 July 2003) was an Iraqi politician, military leader, and the second son of Saddam Hussein. He was appointed as his father's heir apparent in 2000. He was also in charge of the Republ ...

fed opponents of their Baathist rule. These stories attracted worldwide attention and boosted support for military action, in stories with titles such as "See men shredded, then say you don't back war". A year later, it was determined there was no evidence to support the existence of such a machine.

In 2004, former Marine Staff Sgt. Jimmy Massey claimed that he and other Marines intentionally killed dozens of innocent Iraqi civilians, including a 4-year-old girl. His allegations were published by news organizations worldwide, but none of the five journalists – embedded with the troops and approved by the Pentagon – who covered his battalion said they saw reckless or indiscriminate shooting of civilians. The ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' is a regional newspaper based in St. Louis, Missouri, serving the St. Louis metropolitan area. It is the largest daily newspaper in the metropolitan area by circulation, surpassing the '' Belleville News-Democra ...

'' dismissed his claim as "either demonstrably false or exaggerated".

In July 2003 an Iraqi woman, Jumana Hanna, testified that she had been subjected to inhumane treatment by Baathist policemen during two years of imprisonment, including being subjected to electric shocks and raped repeatedly. The story appeared on the front page of ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'', and was presented to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

by then-Deputy Defense Secretary Paul D. Wolfowitz. In January 2005, articles in ''Esquire

Esquire (, ; abbreviated Esq.) is usually a courtesy title. In the United Kingdom, ''esquire'' historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentleman ...

'' and ''The Washington Post'' concluded that none of her allegations could be verified, and that her accounts contained grave inconsistencies. Her husband, who she claimed had been executed in the same prison where she was tortured, was in fact still alive.

Other cases

During the Battle of Jenin, Palestinian officials claimed there was a massacre of civilians in the refugee camp, which was proven false by subsequent international investigations.

During the

During the Battle of Jenin, Palestinian officials claimed there was a massacre of civilians in the refugee camp, which was proven false by subsequent international investigations.

During the 2010 South Kyrgyzstan ethnic clashes

The 2010 South Kyrgyzstan ethnic clashes (; ; ) were clashes between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in southern Kyrgyzstan, primarily in the cities of Osh and Jalal-Abad, in the aftermath of the ouster of former President Kurmanbek Bakiyev on 7 Ap ...

, a rumor spread among ethnic Kyrgyz that Uzbek men had broken into a local women's dormitory and raped several Kyrgyz women. Local police never provided any confirmation that such an assault occurred.

During the Libyan Civil War, Libyan media was reporting atrocities by Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (20 October 2011) was a Libyan military officer, revolutionary, politician and political theorist who ruled Libya from 1969 until Killing of Muammar Gaddafi, his assassination by Libyan Anti-Gaddafi ...

loyalists, who were ordered to perform mass "Viagra-fueled rapes" (see 2011 Libyan rape allegations). A later investigation by Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

has failed to find evidence for these allegations, and in many cases has discredited them, as the rebels were found to have deliberately lied about the claims.

In July 2014, the Russian public broadcaster Channel One aired a report claiming that Ukrainian soldiers in Sloviansk had crucified a three-year-old boy to a board, and later dragged his mother with a tank, causing her death. The account of the only witness interviewed for the report was not corroborated by anyone else, and other media have been unable to confirm the story, despite claims in the testimony that many of the city's inhabitants had been forced to watch the killings. A reporter for ''Novaya Gazeta

''Novaya Gazeta'' (, ) is an independent Russian newspaper. It is known for its critical and investigative coverage of Russian political and social affairs, the Chechen wars, corruption among the ruling elite, and increasing authoritarianism i ...

'' similarly failed to find any other witnesses in the city.

In his announcement of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, Russian President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

baselessly claimed that Ukraine was carrying out genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

in the mainly Russian-speaking Donbas region. In April 2022, Canada's Communications Security Establishment said there was a coordinated effort by the Russian government to promote false reports about Ukraine harvesting organs from dead soldiers, women and children. On 21 September 2022, Vladimir Putin announced a partial mobilisation. To justify Russia's invasion of Ukraine and mobilization, Putin claimed in his address to the Russian audience that the "terror and violence" against the Ukrainian people by the pro-Western "Nazi" regime in Kiev had "taken increasingly horrific, barbaric forms," Ukrainians had been turned into "cannon fodder," and therefore Russia had no choice but to defend "our beloved" in Ukraine.

In the aftermath of the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel

On October 7, 2023, Hamas and several other Palestinians, Palestinian militant groups launched coordinated armed incursions from the Gaza Strip into the Gaza envelope of southern Israel, the first invasion of Israeli territory since the 1948 ...

, Israel was accused of spreading atrocity propaganda to justify its invasion of the Gaza Strip. The alleged propaganda included claims of systematic rape (such as a ''New York Times'' piece titled '' Screams Without Words'') and of babies being beheaded and burned.

See also

* Crucified boy * '' Falsehood in War-Time'' *False flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misrep ...

* Fear mongering

Fearmongering, or scaremongering, is the act of exploiting feelings of fear by using exaggerated rumors of impending danger, usually for personal gain.

Theory

According to evolutionary anthropology and evolutionary biology, humans have a strong ...

* Media coverage of North Korea

* Moral panic

A moral panic is a widespread feeling of fear that some evil person or thing threatens the values, interests, or well-being of a community or society. It is "the process of arousing social concern over an issue", usually perpetuated by moral e ...

* Sensationalism

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emoti ...

* Yellow journalism

In journalism, yellow journalism and the yellow press are American newspapers that use eye-catching headlines and sensationalized exaggerations for increased sales. This term is chiefly used in American English, whereas in the United Kingdom, ...

References

Bibliography

* * Ponsonby, Arthur (1928). Falsehood in Wartime. Containing an Assortment of Lies Circulated Throughout the Nations during the Great War. New York: E.P. Dutton & co., p. 128.Further reading

* Bromley, David G., '' The Politics of Religious Apostasy'', Praeger Publishers, 1998. * Gordon, Gregory SAtrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition

Oxford University Press, 2019. * Gullace, Nicoletta F. (Sept 2011). "Allied Propaganda and World War I: Interwar Legacies, Media Studies, and the Politics of War Guilt". ''History Compass'' 9#9, pp. 686–700. * Shupe, A.D. and Bromley, D.G. (1981). ''

Apostates

Apostasy (; ) is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous religious beliefs. One who ...

and Atrocity Stories: Some parameters in the Dynamics of Deprogramming

Deprogramming is a controversial tactic that seeks to dissuade someone from "strongly held convictions" such as religious beliefs. Deprogramming purports to assist a person who holds a particular belief system—of a kind considered harmful by thos ...

''. In: B.R. Wilson (ed.), ''The Social Impact of New Religious Movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part ...

s'', Barrytown, NY: Rose of Sharon Press, pp. 179–215.

* Théry, Julien (March 2011)"Atrocitas/enormitas. Esquisse pour une histoire de la catégorie de 'crime énorme' du Moyen Âge à l'époque moderne"

Clio@Themis, Revue électronique d'histoire du droit, n. 4.

External links

* Bruendel, SteffenOthering/Atrocity Propaganda

in

1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War

– The Independent

Atrocity propaganda

– The British Library {{Propaganda Journalistic hoaxes Moral panic Black propaganda Psychological warfare techniques Fake news Defamation Information operations and warfare Appeals to emotion Psychological manipulation