Assyrian Palace Relief on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Assyrian sculpture is the sculpture of the ancient

The king is often shown in narrative scenes, and also as a large standing figure in a few prominent places, generally attended by winged genies. A composition repeated twice in what is traditionally called the "throne-room" (though perhaps it was not) of Ashurbanipal's palace at Nimrud shows a "Sacred Tree" or "

The king is often shown in narrative scenes, and also as a large standing figure in a few prominent places, generally attended by winged genies. A composition repeated twice in what is traditionally called the "throne-room" (though perhaps it was not) of Ashurbanipal's palace at Nimrud shows a "Sacred Tree" or "

File:Sculpted reliefs depicting Ashurbanipal, the last great Assyrian king, hunting lions, gypsum hall relief from the North Palace of Nineveh (Irak), c. 645-635 BC, British Museum (16722131531).jpg, Dying lion, '' Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal'', North Palace,

Lamassu were protective minor deities or spirits, the Assyrian version of the "human-headed bull" figure that had long figured in Mesopotamian mythology and art. Lamassu have wings, a male human head with the elaborate headgear of a divinity, and the elaborately braided hair and beards shared with royalty. The body is that of either a bull or a lion, the form of the feet being the main difference. Prominent pairs of ''lamassu'' were typically placed at entrances in palaces, facing the street and also internal courtyards. They were "double-aspect" figures on corners, in high relief, a type earlier found in Hittite art. From the front they appear to stand, and from the side, walk, and in earlier versions have five legs, as is apparent when viewed obliquely. ''Lamassu'' do not generally appear as large figures in the low-relief schemes running round palace rooms, where winged genie figures are common, but they sometimes appear within narrative reliefs, apparently protecting the Assyrians.

The colossal entrance way figures were often followed by a hero grasping a wriggling lion, also colossal and in high relief; these and some genies beside ''lamassu'' are generally the only other types of high relief in Assyrian sculpture. The heroes continue the Master of Animals tradition in Mesopotamian art, and may represent

Lamassu were protective minor deities or spirits, the Assyrian version of the "human-headed bull" figure that had long figured in Mesopotamian mythology and art. Lamassu have wings, a male human head with the elaborate headgear of a divinity, and the elaborately braided hair and beards shared with royalty. The body is that of either a bull or a lion, the form of the feet being the main difference. Prominent pairs of ''lamassu'' were typically placed at entrances in palaces, facing the street and also internal courtyards. They were "double-aspect" figures on corners, in high relief, a type earlier found in Hittite art. From the front they appear to stand, and from the side, walk, and in earlier versions have five legs, as is apparent when viewed obliquely. ''Lamassu'' do not generally appear as large figures in the low-relief schemes running round palace rooms, where winged genie figures are common, but they sometimes appear within narrative reliefs, apparently protecting the Assyrians.

The colossal entrance way figures were often followed by a hero grasping a wriggling lion, also colossal and in high relief; these and some genies beside ''lamassu'' are generally the only other types of high relief in Assyrian sculpture. The heroes continue the Master of Animals tradition in Mesopotamian art, and may represent

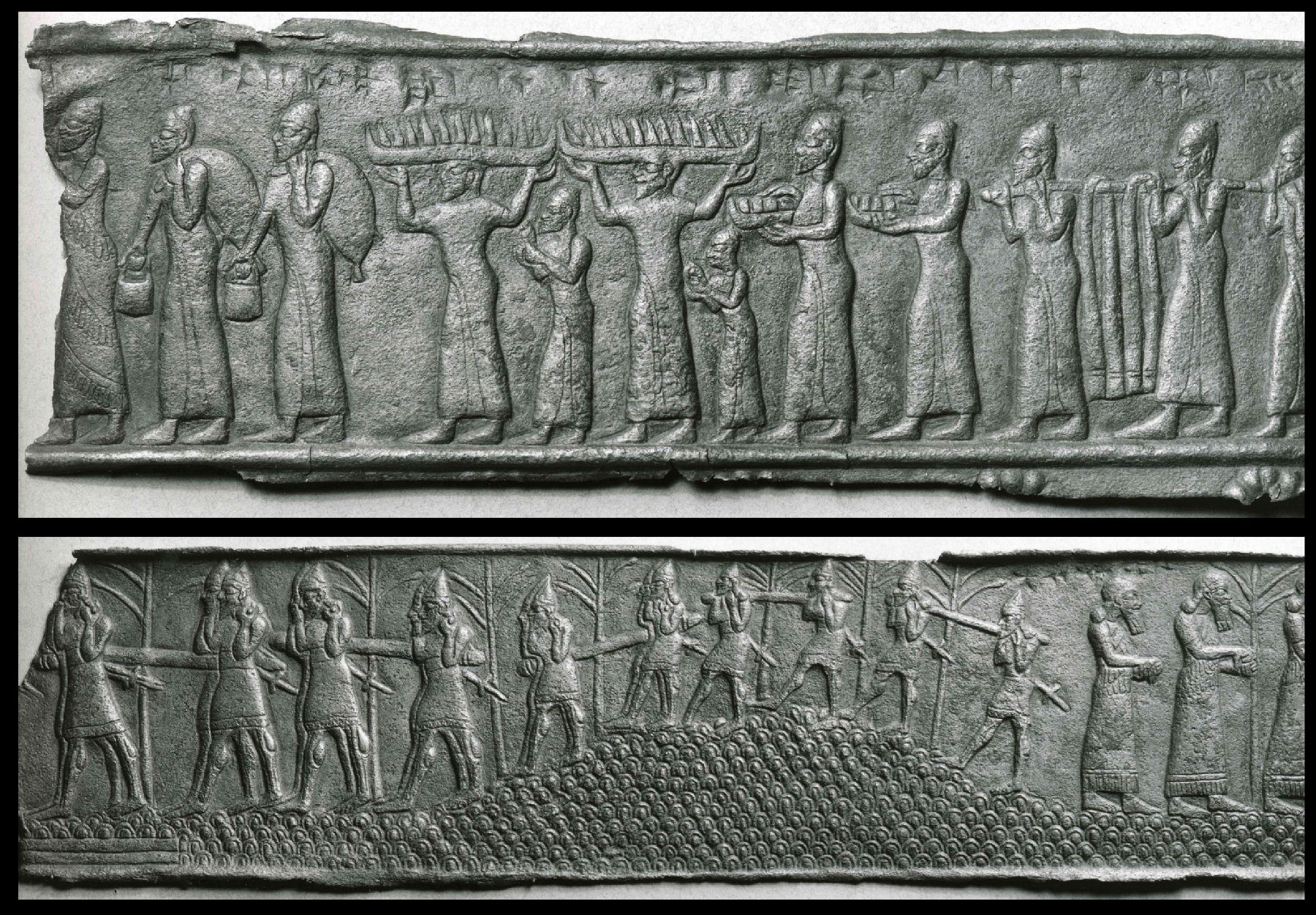

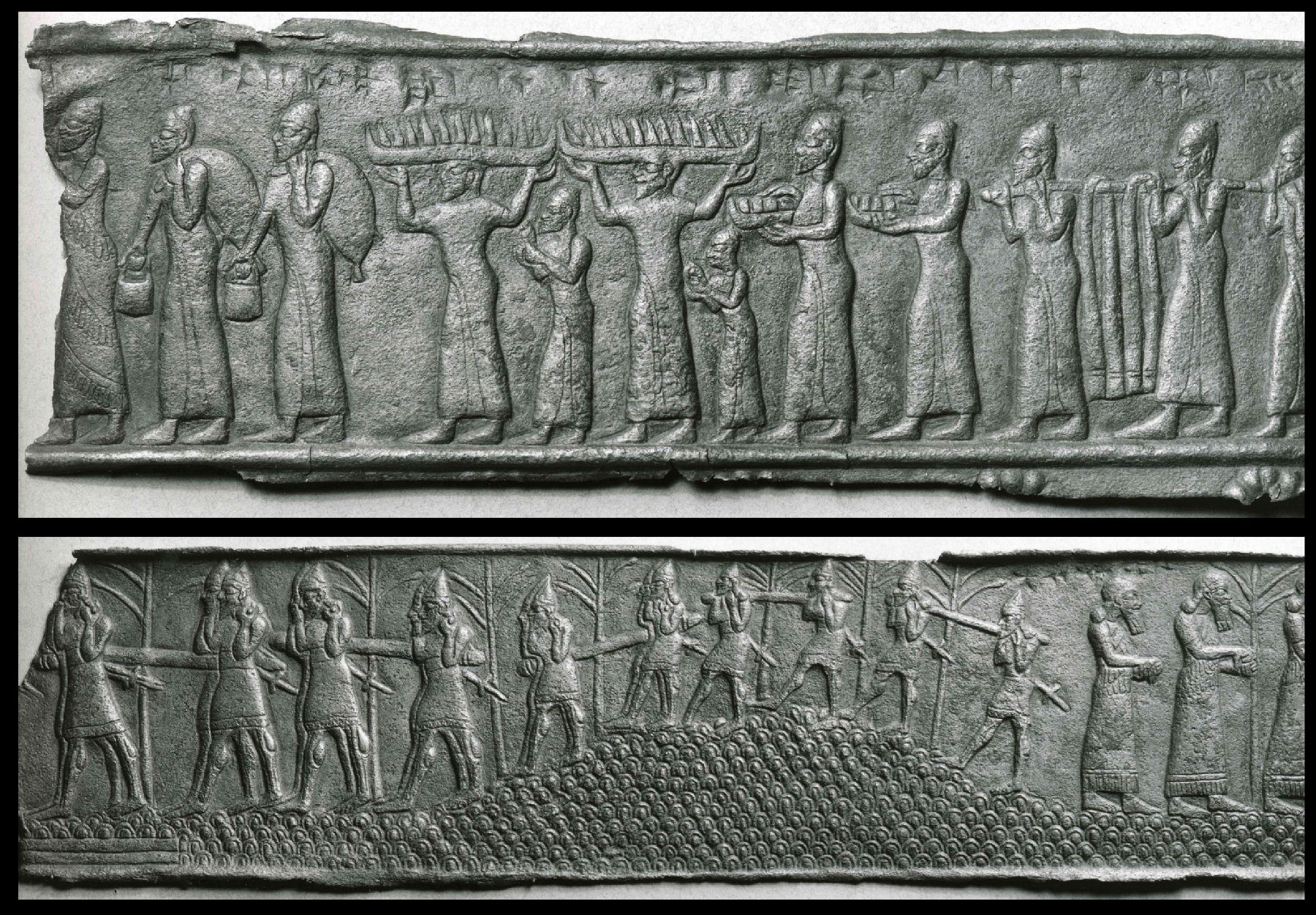

Apart from the alabaster wall reliefs, all found in palaces, other objects carrying relatively large reliefs are bronze strips used to reinforce and decorate large gates. Parts of three sets have survived, all from the 9th century BC and the relatively minor city of Imgur-Enlil, modern Balawat. The Balawat Gates were all double gates about 20 foot high, with both the front and back sides decorated with eight bronze repoussé strips, each carrying two registers of narrative reliefs some five inches high. There were presumably equivalents at other Assyrian sites, but at the collapse of the empire the buildings at Balawat caught fire "before they had been efficiently looted" by the enemy, and remained hidden in the ashes and rubble; gypsum slabs were not worth the trouble of looting, unlike bronze. The subjects were similar to the wall reliefs, but on a smaller scale; a typical band is 27 centimetres high, 1.8 metres wide, and only a millimetre thick.

In stone there are reliefs of a similar size on some stelae, most notably two in rectangular

Apart from the alabaster wall reliefs, all found in palaces, other objects carrying relatively large reliefs are bronze strips used to reinforce and decorate large gates. Parts of three sets have survived, all from the 9th century BC and the relatively minor city of Imgur-Enlil, modern Balawat. The Balawat Gates were all double gates about 20 foot high, with both the front and back sides decorated with eight bronze repoussé strips, each carrying two registers of narrative reliefs some five inches high. There were presumably equivalents at other Assyrian sites, but at the collapse of the empire the buildings at Balawat caught fire "before they had been efficiently looted" by the enemy, and remained hidden in the ashes and rubble; gypsum slabs were not worth the trouble of looting, unlike bronze. The subjects were similar to the wall reliefs, but on a smaller scale; a typical band is 27 centimetres high, 1.8 metres wide, and only a millimetre thick.

In stone there are reliefs of a similar size on some stelae, most notably two in rectangular

There are very few large free-standing Assyrian statues and, with one possible exception (below), none have been found of the major divinities in their temples. Possibly others existed; any in precious metals would have been looted as the empire fell. Two statues of kings are similar to the portraits in palace reliefs, though seen frontally. They came from temples, where they showed the king's devotion to the deity. The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II is in the British Museum, and that of

There are very few large free-standing Assyrian statues and, with one possible exception (below), none have been found of the major divinities in their temples. Possibly others existed; any in precious metals would have been looted as the empire fell. Two statues of kings are similar to the portraits in palace reliefs, though seen frontally. They came from temples, where they showed the king's devotion to the deity. The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II is in the British Museum, and that of

File:Hérosmaîtrisantunlion.jpg, High relief hero clutching lion, from the entrance to the throne room at

Monument de Ninive

' was published, a sumptuously illustrated and exemplary

Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) was in the early 1840s "a roving agent attached to the embassy at

Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) was in the early 1840s "a roving agent attached to the embassy at

Assyrian Relief at V&A

/ref>

subscription required

* Hugh Honour and John Fleming, ''A World History of Art'', 1st edn. 1982 (many later editions), Macmillan, London, page refs to 1984 Macmillan 1st edn. paperback. * Hoving, Thomas. ''Greatest Works of Western Civilization'', 1997, Artisan, New York, *Kreppner, Florian Janoscha, "Public Space in Nature: The Case of Neo-Assyrian Rock-Reliefs", ''Altorientalische Forschungen'', 29/2 (2002): 367–383

online at Academia.edu

*Oates, D. and J. Oates, ''Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed'', 2001, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq

full PDF (332 pages)

*Reade, Julian, ''Assyrian Sculpture'', 1998 (2nd edn.), The British Museum Press,

google books

*Russell, John M., ''Sennacherib's ‘Palace without Rival’ at Nineveh'', 1991, Chicago * * Hunting in art War art

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

n states, especially the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

of 911 to 612 BC, which was centered around the city of Assur in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

(modern-day Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

) which at its height, ruled over all of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

and Egypt, as well as portions of Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

and modern-day Iran and Armenia. It forms a phase of the art of Mesopotamia

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the record from early hunter-gatherer societies (8th millennium BC) on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian Empire, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replace ...

, differing in particular because of its much greater use of stone and gypsum alabaster for large sculpture.

Much the best-known works are the huge ''lamassu

''Lama'', ''Lamma'', or ''Lamassu'' (Cuneiform: , ; Sumerian language, Sumerian: lammař; later in Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''lamassu''; sometimes called a ''lamassuse'') is an Mesopotamia, Assyrian protective deity.

Initially depicted as ...

'' guarding entrance ways, and Assyrian palace reliefs on thin slabs of alabaster, which were originally painted, at least in part, and fixed on the wall all round the main rooms of palaces. Most of these are in museums in Europe or America, following a hectic period of excavations from 1842 to 1855, which took Assyrian art from being almost completely unknown to being the subject of several best-selling books, and imitated in political cartoons.

The palace reliefs contain scenes in low relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

which glorify the king, showing him at war, hunting, and fulfilling other kingly roles. Many works left ''in situ'', or in museums local to their findspots, have been deliberately destroyed in the recent occupation of the area by ISIS

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

, the pace of destruction reportedly increasing in late 2016, with the Mosul offensive.

Other surviving types of art include many cylinder seals, a few rock reliefs, reliefs and statues from temples, bronze relief strips used on large doors, and small quantities of metalwork. A group of sixteen bronze weights shaped as lions with bilingual inscriptions in both cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

and Phoenician characters, were discovered at Nimrud.

The Nimrud ivories

The Nimrud ivories are a large group of small carved ivory plaques and figures dating from the 9th to the 7th centuries BC that were excavated from the Assyrian city of Nimrud (in modern Ninawa Governorate, Ninawa in Iraq) during the 19th and 20 ...

, an important group of small plaques which decorated furniture, were found in a palace storeroom near reliefs, but they came from around the Mediterranean, with relatively few made locally in an Assyrian style.

Palace reliefs

The palace reliefs were fixed to the walls of royal palaces forming continuous strips along the walls of large halls. The style apparently began after about 879 BC, when Ashurnasirpal II moved the capital toNimrud

Nimrud (; ) is an ancient Assyrian people, Assyrian city (original Assyrian name Kalḫu, biblical name Calah) located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah (), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. ...

, near modern Mosul

Mosul ( ; , , ; ; ; ) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. It is the second largest city in Iraq overall after the capital Baghdad. Situated on the banks of Tigris, the city encloses the ruins of the ...

in northern Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

. Thereafter, new royal palaces, of which there was typically one per reign, were extensively decorated in this way for the roughly 250 years until the end of the Assyrian Empire. There was subtle stylistic development, but a very large degree of continuity in subjects and treatment.

Compositions are arranged on slabs, or orthostats, typically about 7 feet high, using between one and three horizontal registers of images, with scenes generally reading from left to right. The sculptures are often accompanied with inscriptions in cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

script, explaining the action or giving the name and extravagant titles of the king. Heads and legs are shown in profile, but torsos in a front or three-quarters view, as in earlier Mesopotamian art. Eyes are also largely shown frontally. Some panels show only a few figures at close to life-size, such scenes usually including the king and other courtiers, but depictions of military campaigns include dozens of small figures, as well as many animals and attempts at showing landscape settings.

Campaigns focus on the progress of the army, including the fording of rivers, and usually culminates in the siege of a city, followed by the surrender and paying of tribute, and the return of the army home. A full and characteristic set shows the campaign leading up to the siege of Lachish in 701; it is the "finest" from the reign of Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

, from his palace at Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

and now in the British Museum. Ernst Gombrich observed that none of the many casualties ever come from the Assyrian side. Another famous sequence there shows the '' Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal'', in fact the staged and ritualized killing by King Ashurbanipal of lions already captured and released into an arena, from the North Palace at Nineveh. The realism of the lions has always been praised, and the scenes are often regarded as "the supreme masterpieces of Assyrian art", although the pathos modern viewers tend to feel was perhaps not part of the Assyrian response.

There are many reliefs of minor supernatural beings, called by such terms as " winged genie", but the major Assyrian deities are only represented by symbols. The "genies" often perform a gesture of purification, fertilization or blessing with a bucket and cone; the meaning of this remains unclear., Especially on larger figures, details and patterns on areas such as costumes, hair and beards, tree trunks and leaves, and the like, are very meticulously carved. More important figures are often shown larger than others, and in landscapes more distant elements are shown higher up, but not smaller than, those in the foreground, though some scenes have been interpreted as using scale to indicate distance. Other scenes seem to repeat a figure in a succession of different moments, performing the same action, most famously a charging lion. But these were apparently experiments that remain unusual.

The king is often shown in narrative scenes, and also as a large standing figure in a few prominent places, generally attended by winged genies. A composition repeated twice in what is traditionally called the "throne-room" (though perhaps it was not) of Ashurbanipal's palace at Nimrud shows a "Sacred Tree" or "

The king is often shown in narrative scenes, and also as a large standing figure in a few prominent places, generally attended by winged genies. A composition repeated twice in what is traditionally called the "throne-room" (though perhaps it was not) of Ashurbanipal's palace at Nimrud shows a "Sacred Tree" or "Tree of Life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythology, mythological, religion, religious, and philosophy, philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The ...

" flanked by two figures of the king, with winged genies using the bucket and cone behind him. Above the tree one of the major gods, perhaps Ashur the chief god, leans out of a winged disc, relatively small in scale. Such scenes are shown elsewhere on the robe of the king, no doubt reflecting embroidery on the real costumes, and the major gods are normally shown in discs or purely as symbols hovering in the air. Elsewhere the tree is often attended to by genies.

Women are relatively rarely shown, and then usually as prisoners or refugees; an exception is a "picnic" scene showing Ashurbanipal with his queen. The many beardless royal attendants can probably be assumed to be eunuch

A eunuch ( , ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function. The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2 ...

s, who ran much of the administration of the empire, unless they also have the shaved heads and very tall hats of priests. Kings are often accompanied by several courtiers, the closest to the king probably often being the appointed heir, who was not necessarily the oldest son.

The enormous scales of the palace schemes allowed narratives to be shown at an unprecedentedly expansive pace, making the sequence of events clear and allowing richly detailed depictions of the activities of large numbers of figures, not to be paralleled until the Roman narrative column reliefs of the Column of Trajan and Column of Marcus Aurelius.

Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

File:Lachish Relief, British Museum.jpg, Prisoners and cavalry, Lachish relief

File:Sargon II and dignitary.jpg, Sargon II (right), probably facing his heir Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

, Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city ...

File:2015-12 Deux serviteurs portant un siège et un vase AO 19879.jpg, Eunuch attendants carry furniture and a bowl

Lamassu

Lamassu were protective minor deities or spirits, the Assyrian version of the "human-headed bull" figure that had long figured in Mesopotamian mythology and art. Lamassu have wings, a male human head with the elaborate headgear of a divinity, and the elaborately braided hair and beards shared with royalty. The body is that of either a bull or a lion, the form of the feet being the main difference. Prominent pairs of ''lamassu'' were typically placed at entrances in palaces, facing the street and also internal courtyards. They were "double-aspect" figures on corners, in high relief, a type earlier found in Hittite art. From the front they appear to stand, and from the side, walk, and in earlier versions have five legs, as is apparent when viewed obliquely. ''Lamassu'' do not generally appear as large figures in the low-relief schemes running round palace rooms, where winged genie figures are common, but they sometimes appear within narrative reliefs, apparently protecting the Assyrians.

The colossal entrance way figures were often followed by a hero grasping a wriggling lion, also colossal and in high relief; these and some genies beside ''lamassu'' are generally the only other types of high relief in Assyrian sculpture. The heroes continue the Master of Animals tradition in Mesopotamian art, and may represent

Lamassu were protective minor deities or spirits, the Assyrian version of the "human-headed bull" figure that had long figured in Mesopotamian mythology and art. Lamassu have wings, a male human head with the elaborate headgear of a divinity, and the elaborately braided hair and beards shared with royalty. The body is that of either a bull or a lion, the form of the feet being the main difference. Prominent pairs of ''lamassu'' were typically placed at entrances in palaces, facing the street and also internal courtyards. They were "double-aspect" figures on corners, in high relief, a type earlier found in Hittite art. From the front they appear to stand, and from the side, walk, and in earlier versions have five legs, as is apparent when viewed obliquely. ''Lamassu'' do not generally appear as large figures in the low-relief schemes running round palace rooms, where winged genie figures are common, but they sometimes appear within narrative reliefs, apparently protecting the Assyrians.

The colossal entrance way figures were often followed by a hero grasping a wriggling lion, also colossal and in high relief; these and some genies beside ''lamassu'' are generally the only other types of high relief in Assyrian sculpture. The heroes continue the Master of Animals tradition in Mesopotamian art, and may represent Enkidu

Enkidu ( ''EN.KI.DU10'') was a legendary figure in Mesopotamian mythology, ancient Mesopotamian mythology, wartime comrade and friend of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. Their exploits were composed in Sumerian language, Sumerian poems and in the Akk ...

, a central figure in the ancient Mesopotamian ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian language, Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh (formerly read as Sumerian "Bilgames"), king of Uruk, some of ...

''. In the palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city ...

, a group of at least seven ''lamassu'' and two such heroes with lions surrounded the entrance to the "throne room", "a concentration of figures which produced an overwhelming impression of power". The arrangement was repeated in Sennacherib's palace at Nineveh, with a total of ten lamassu. Other accompanying figures for colossal ''lamassu'' are winged genies with the bucket and cone, thought to be the equipment for a protective or purifying ritual.

''Lamassu'' also appear on cylinder seals. Several examples left ''in situ'' in northern Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

have been destroyed in the 2010s by ISIL when they occupied the area. Colossal ''lamassu'' also guarded the start of the large canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface ...

s built by the Assyrian kings. In the case of temples, pairs of colossal lions guarding the entrances have been found.

Construction

There are outcrops of the "Mosul marble" gypsum rock normally used at several places in the Assyrian realm, though not especially close to the capitals. The rock is very soft and slightly soluble in water, and exposed faces degraded, and needed to be cut into before usable stone was reached. There are reliefs showing quarrying forSennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

's new palace at Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

, though concentrating on the production of large lamassu

''Lama'', ''Lamma'', or ''Lamassu'' (Cuneiform: , ; Sumerian language, Sumerian: lammař; later in Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''lamassu''; sometimes called a ''lamassuse'') is an Mesopotamia, Assyrian protective deity.

Initially depicted as ...

. Blocks were extracted, using prisoners of war, and sawed into slabs with long iron saws. This may have happened at the palace site, which is certainly where the carving of orthostats was done, after the slabs had been fixed into place as a facing to a mud-brick wall, using lead dowels and clamps, with the bottoms resting on a bed of bitumen

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscosity, viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American Engl ...

. For some reliefs an "attractive fossiliferous limestone" is used, as in several rooms in the South-West Palace at Nineveh. In contrast to the orthostats, the ''lamassu'' were carved, or at least partly so, at the quarry, no doubt to reduce their enormous weight.

The alabaster stone is soft but not brittle, and very suitable for detailed carving with early Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

tools. There can be considerable differences in style, and quality, between adjacent panels, suggesting that different master carvers were allocated these. Probably the master drew or incised the design on the slab before a team of carvers laboriously cut away the background areas and finished carving the figures. Scribes then set out any inscriptions for cutters to follow, after which the slab was polished smooth, and any paint added. Scribes are shown directing carvers in another relief (on the Balawat Gates) showing the creation of a rock relief; presumably they ensured that the depiction of royal and religious aspects of the subjects was as it should be.

The reliefs only covered the lower parts of the walls of rooms in the palaces, and higher areas were often painted, at least in patterns, and at least sometimes with other figures. Brightly coloured carpets on the floor completed what was probably a striking decor, largely in primary colours. None of these have survived, but we have some door-sills carved with repeated geometric motifs, presumed to imitate the carpets.

After the palaces were abandoned and lost their wooden roofs, the unbaked mud-brick walls gradually collapsed, covering the space in front of the reliefs, and largely protecting them from further damage from the weather. Relatively few traces of paint remain, and these are often on heads and faces – hair and beards were black, and at least the whites of eyes white. Possibly metal leaf was used on some elements, such as small scenes shown decorating textiles. Julian Reade concludes that "It is nonetheless puzzling that more traces of painting n sculpturehave not been recorded".

Other narrative reliefs

Apart from the alabaster wall reliefs, all found in palaces, other objects carrying relatively large reliefs are bronze strips used to reinforce and decorate large gates. Parts of three sets have survived, all from the 9th century BC and the relatively minor city of Imgur-Enlil, modern Balawat. The Balawat Gates were all double gates about 20 foot high, with both the front and back sides decorated with eight bronze repoussé strips, each carrying two registers of narrative reliefs some five inches high. There were presumably equivalents at other Assyrian sites, but at the collapse of the empire the buildings at Balawat caught fire "before they had been efficiently looted" by the enemy, and remained hidden in the ashes and rubble; gypsum slabs were not worth the trouble of looting, unlike bronze. The subjects were similar to the wall reliefs, but on a smaller scale; a typical band is 27 centimetres high, 1.8 metres wide, and only a millimetre thick.

In stone there are reliefs of a similar size on some stelae, most notably two in rectangular

Apart from the alabaster wall reliefs, all found in palaces, other objects carrying relatively large reliefs are bronze strips used to reinforce and decorate large gates. Parts of three sets have survived, all from the 9th century BC and the relatively minor city of Imgur-Enlil, modern Balawat. The Balawat Gates were all double gates about 20 foot high, with both the front and back sides decorated with eight bronze repoussé strips, each carrying two registers of narrative reliefs some five inches high. There were presumably equivalents at other Assyrian sites, but at the collapse of the empire the buildings at Balawat caught fire "before they had been efficiently looted" by the enemy, and remained hidden in the ashes and rubble; gypsum slabs were not worth the trouble of looting, unlike bronze. The subjects were similar to the wall reliefs, but on a smaller scale; a typical band is 27 centimetres high, 1.8 metres wide, and only a millimetre thick.

In stone there are reliefs of a similar size on some stelae, most notably two in rectangular obelisk

An obelisk (; , diminutive of (') ' spit, nail, pointed pillar') is a tall, slender, tapered monument with four sides and a pyramidal or pyramidion top. Originally constructed by Ancient Egyptians and called ''tekhenu'', the Greeks used th ...

form, both with stepped tops like ziggurats. These are the early 11th-century White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I and the 9th century Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, both in the British Museum, which also has the fragmentary "Broken Obelisk" and " Rassam Obelisk". Both have reliefs on all four sides in eight and five registers respectively, and long inscriptions describing the events. The Black and Rassam Obelisks were both set up in what seems to have been the central square in the citadel of Nimrud, presumably a very public space, and the White in Nineveh. All record much the same types of scenes as the narrative sections of wall-relief, and the gates. The Black Obelisk concentrates on scenes of the bringing of tribute from conquered kingdoms, including Israel, while the White also has scenes of war, hunting, and religious figures. The White Obelisk, from 1049–1031, and the "Broken Obelisk" from 1074–1056, predate the earliest known wall-reliefs by 160 years or more, but are respectively in worn and fragmentary condition.

The Black Obelisk is of special interest as the lengthy inscriptions, with names of places and rulers that could be related to other sources, were of importance in the decipherment of cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

script. The Obelisk contains the earliest writing mentioning both the Persian and Jewish peoples, and confirmed some of the events described in the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, which in the 19th century was regarded as timely support for texts whose historical accuracy was under increasing attack. Other, much smaller pieces with helpful inscriptions were a set of sixteen weight measures in the form of lions.

Statues and portrait stelae

There are very few large free-standing Assyrian statues and, with one possible exception (below), none have been found of the major divinities in their temples. Possibly others existed; any in precious metals would have been looted as the empire fell. Two statues of kings are similar to the portraits in palace reliefs, though seen frontally. They came from temples, where they showed the king's devotion to the deity. The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II is in the British Museum, and that of

There are very few large free-standing Assyrian statues and, with one possible exception (below), none have been found of the major divinities in their temples. Possibly others existed; any in precious metals would have been looted as the empire fell. Two statues of kings are similar to the portraits in palace reliefs, though seen frontally. They came from temples, where they showed the king's devotion to the deity. The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II is in the British Museum, and that of Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''Šulmānu-ašarēdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 859 BC to 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campaigns against the eastern tribes, the Babylonians, the nations o ...

in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

.

There is a unique female nude statue in the British Museum, missing its extremities, which was found in the temple of Ishtar at Nineveh. The pubic hair is carefully represented. It carries an inscription on the back that King Ashur-bel-kala erected it for the "titilation" or enjoyment of the people. It might represent Ishtar, goddess of love among other things, in which case it would be the only known Assyrian statue of a major divinity. All these have standing poses, though seated statues were already known in Mesopotamian art, for example about a dozen statues of Gudea

Approximately twenty-seven statues of Gudea have been found in southern Mesopotamia. Gudea was a ruler (Ensí, ensi) of the state of Lagash between and 2124 BC, and the statues demonstrate a very sophisticated level of craftsmanship for that ...

, who ruled Lagash

Lagash (; cuneiform: LAGAŠKI; Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''Lagaš'') was an ancient city-state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash ( ...

c. 2144 – 2124 BC.

Like other Near-Eastern cultures, the Assyrians erected stelae for various purposes, including marking boundaries. Many just carry inscriptions, but there are some with significant relief sculpture, mostly a large standing portrait of the king of the day, pointing at symbols of the gods, similar in pose to those in palace reliefs, surrounded by a round-topped frame.

Similar figures of kings are shown in rock reliefs, mostly around the edges of the empire. Those shown being made on the Balawat Gates are presumably the ones surviving in poor condition near the Tigris Tunnel. The Assyrians probably took the form from the Hittites; the sites chosen for their 49 recorded reliefs often also make little sense if "signalling" to the general population was the intent, being high and remote, but often near water. The Neo-Assyrians recorded in other places, including metal reliefs on the Balawat Gates showing them being made, the carving of rock reliefs, and it has been suggested that the main intended audience was the gods, the reliefs and the inscriptions that often accompany them being almost of the nature of a "business report" submitted by the ruler. A canal system built by the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

(reigned 704–681 BC) to supply water to Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

was marked by a number of reliefs showing the king with gods.

Other reliefs at the Tigris tunnel, a cave in modern Turkey believed to be the source of the river Tigris

The Tigris ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the eastern of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian Desert, Syrian and Arabia ...

, are "almost inaccessible and invisible for humans". Probably built by Sennacherib's son Esarhaddon, Shikaft-e Gulgul is a late example in modern Iran, apparently related to a military campaign. The Assyrians added to the Commemorative stelae of Nahr el-Kalb in modern Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, where Ramses II, Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

of Egypt, had rather optimistically commemorated the boundary of his empire many centuries earlier; many later rulers added to the collection. The Assyrian examples were perhaps significant in suggesting the style of the much more ambitious Persian tradition, beginning with the Behistun relief and inscription, made around 500 BC for Darius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

, on a far grander scale, reflecting and proclaiming the power of the Achaemenid empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

.

Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city ...

File:BM; RM6 - ANE, Assyrian Sculpture 32 -East (N), Centre Island + North Wall- ~ Assyrian Empire + -Lamassu, Stela's, Statue's, Obelisk's, Relief Panel's & Full Projection.1.jpg, Group displayed in the British Museum, including a lion from a temple entrance, and the Black and White Obelisks

File:black-obelisk.jpg, The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III in the British Museum, the White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I just behind

File:The Assyrian king Shalmaneser III receives tribute from Sua, king of Gilzanu, The Black Obelisk..JPG, Shalmaneser III receives tribute from Sua, king of Gilzanu, on the Black Obelisk

File:Assyrian statue ME124963 (1).jpg, Unique Assyrian female nude statue from the temple of Ishtar at Nineveh

File:Shamshi-Adad V-2.jpg, Stela of Shamshi-Adad V

File:Assyrian Stele - British Museum.jpg, Three royal stelae at the British Museum

Lion-shaped weight-Sb 2718-P5280901-gradient (cropped).jpg, Lion weight; 6th-4th century BC; bronze; height: 29.5 cm, width: 24.8 cm; Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

Excavations

Iraq was part of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

throughout the 19th century, and the government was content to allow foreign excavations and the removal of finds with little hindrance. Even in the 1870s excavators were often only regulated by a regime intended for mining operations, and had to pay a tax based on a proportion of the value of material removed.

The character of the palace reliefs made excavation relatively straightforward, if the right site was chosen. Assyrian palaces were built on high mud-brick platforms. Test trenches were started in various directions, and once one of them had hit sculpture, the trenches had only to follow the lines of the wall, often through a whole suite of rooms. Most trenches could be open to the sky, but at Nimrud, where one palace overlay another, tunnels were necessary in places. Layard estimated "that he had exposed nearly two miles of sculptured walls in Sennacherib's palace alone", not to mention the Library of Ashurbanipal

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BCE, including texts in ...

he found there. His excavation practices left a lot to be desired by modern standards; the centres of rooms were not only not excavated, but the material removed from the trench in one room might be deposited in another, compromising later excavations. Typically the slabs were sawn to roughly a third of their original depth, to save weight in carrying them back to Europe, which was typically more complicated and difficult than digging them up.

Botta

The first hint of future discoveries came in 1820 when Claudius Rich, British Resident (a sort of local ambassador orconsul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

) in Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

, and an early scholar of the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

, went to Mosul and the site of ancient Nineveh, where he was told of a large relief panel that had been found and soon broken up. His account was published in 1836; he also brought back two small fragments. In 1842 the French consul in Mosul, Paul-Émile Botta, hired men to dig at Kuyunjik, the largest mound at Nineveh. Little was found until a local farmer suggested they try Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city ...

(ancient Dur-Sharrukin) nearby, where "a short trial was dramatically successful", as a palace of Sargon II was found a few feet below the surface, with plentiful reliefs, although they had been burned and disintegrated easily.

Press reports of Botta's finds, from May 1843, interested the French government, who sent him funds and the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

The () is a French learned society devoted to history, founded in February 1663 as one of the five academies of the . The academy's scope was the study of ancient inscriptions (epigraphy) and historical literature (see Belles-lettres).

History ...

sent him Eugène Flandin (1809–1889), an artist who had already made careful archaeological drawings of Persian antiquities in a long trip beginning in 1839. Botta decided there was no more to find at the site in October 1844, and concentrated on the difficult task of getting his finds back to Paris, where the first large consignments did not arrive until December 1846. Botta left the two huge ''lamassu'' now in the British Museum as too large to transport; Henry Rawlinson, by now British Resident in Baghdhad, sawed them into several pieces for transport in 1849. In 1849 Monument de Ninive

' was published, a sumptuously illustrated and exemplary

monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

in 4 volumes by Botta and Flandin.

Layard and Rassam

Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) was in the early 1840s "a roving agent attached to the embassy at

Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) was in the early 1840s "a roving agent attached to the embassy at Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

", who had already visited Nimrud in 1840. In 1845 he persuaded Sir Stratford Canning, the ambassador in Constantinople, to personally fund an expedition to excavate there. On his first day digging at Nimrud, with only six workers in November 1845, slabs were found, initially only with inscriptions, but soon with reliefs. He continued to dig until June 1847, with the British government, through the British Museum, taking over the funding from Canning in late 1846, repaying his expenditure. The volume of finds was such that getting them back to Britain was a major task, and many pieces either were reburied, or reached other countries. Layard had recruited the 20-year old Hormuzd Rassam in Mosul, where his brother was British Vice-consul, to handle the pay and supervision of the diggers, and encouraged the development of his career as a diplomat and archaeologist.

Layard returned to England in June 1847, also taking Rassam, who he had arranged to study at Cambridge. He left a few workers, mainly to keep other diggers off the sites, as the French were digging again. His finds were arriving in London, to great public interest, which he greatly increased by publishing a string of books, especially ''Nineveh and its Remains'' in 1849. The mistaken title arose because Henry Rawlinson had at that point become convinced that the Nimrud site was actually the ancient Nineveh, though he changed his mind soon after. By October 1849 Layard was back in Mosul, accompanied by the artist Frederick Cooper, and continued to dig until April 1851, after which Rassam took charge of the excavations. By this stage, thanks to Rawlinson and other linguists working on the tablets and inscriptions brought back and other material, the Assyrian cuneiform was at the least becoming partly understood, a task that progressed well over the next decade.

Initially Rassam's finds dwindled, in terms of large objects, and the British even agreed to cede the rights to half the Kuyunjik mound to the French, whose new consul, Victor Place, had resumed digging at Khorsabad. The British funds were running out by December 1853, when Rassam hit upon the palace of Ashurbanipal, which was "in some respects the finest sculptured palace of all", in the new French area of Kuyunjik. Fortunately, Place had not started digging there, and according to Rassam "it was an established rule that whenever one discovered a new palace, no one else could meddle with it, and thus,... I had secured it for England". The new palace took until 1855 to clear, being finished by the Assyrian Exploration Fund, established in 1853 to dig for the benefit of British collections.

Although it was not yet realized, by "the close of excavations in 1855, the hectic Heroic Age of Assyrian archaeology ended", with the great majority of surviving Assyrian sculpture found. Work has continued up to the present day, but no new palaces have been found at the capitals, and finds have mostly been isolated pieces, such as Rassam's discovery in 1878 of two of the Balawat Gates. Many of the pieces reburied have been re-excavated, some very quickly by art dealers, and others by the Iraqi government in the 1960s, leaving them on display ''in situ'' for visitors, after the sites were configured as museums. These were already damaged in wars in the 1990s, and have probably been systematically destroyed by Daesh in the 2010s.

Collections

As a result of the history of excavations, much the best single collection is in theBritish Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, followed by the site museums and other collections in Iraq, which in the 20th century were the largest holdings when taken together, though after the wars of the 21st century their current holdings are uncertain. The fate of the considerable number of pieces that have been found and then reburied is also uncertain. At the peak of excavations, the volume found was too large for the British and French to manage, and many pieces either were diverted at some point on their journey to Europe, or were given away by the museums. Other pieces were excavated by diggers working for dealers. As a result, there are significant groups of large ''lamassu'' corner figures and palace relief panels in Paris, Berlin, New York, and Chicago. Many other museums have panels, especially a group of college museums in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

, with the museum at Dartmouth College having seven panels. Altogether there are some 75 pieces in the United States.

Apart from the British Museum, in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the Ashmolean Museum has 10 reliefs (2 large, 8 small) Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery has 3 large reliefs, and the National Museum of Scotland

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, is a museum of Scottish history and culture.

It was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, ...

(2.4 x 2.2 m), and Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

one relief each./ref>

Notes

References

*Cohen, Ada, Kangas, Stephen E., ''Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II'', 2010, University Press of New England, * Frankfort, Henri, ''The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient'', Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), *"Grove": Russell, John M., Section 6. "c 1000–539 BC., (i) Neo-Assyrian." in Dominique Collon, et al. "Mesopotamia, §III: Sculpture." Grove Art Online,Oxford Art Online

Oxford Art Online is an Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press ...

, Oxford University Press, accessed 19 November 2016subscription required

* Hugh Honour and John Fleming, ''A World History of Art'', 1st edn. 1982 (many later editions), Macmillan, London, page refs to 1984 Macmillan 1st edn. paperback. * Hoving, Thomas. ''Greatest Works of Western Civilization'', 1997, Artisan, New York, *Kreppner, Florian Janoscha, "Public Space in Nature: The Case of Neo-Assyrian Rock-Reliefs", ''Altorientalische Forschungen'', 29/2 (2002): 367–383

online at Academia.edu

*Oates, D. and J. Oates, ''Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed'', 2001, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq

full PDF (332 pages)

*Reade, Julian, ''Assyrian Sculpture'', 1998 (2nd edn.), The British Museum Press,

Further reading

*Collins, Paul, ''Assyrian Palace Sculptures'', 2008, British Museum, , 9780714111674 *Crawford, Vaughn Emerson, Harper, Prudence Oliver, Pittman, Holly, ''Assyrian Reliefs and Ivories in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Palace Reliefs of Assurnasirpal II and Ivory Carvings from Nimrud'', 1980, Metropolitan Museum of Art, , 9780870992605 *Kertai, David, ''The Architecture of Late Assyrian Royal Palaces'', 2015, Oxford University Press, , 9780198723189 *Larsen, Mogens Trolle, ''The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land, 1840–1860'', 1996, Psychology Press, , 9780415143561 *Ornan, Tallay, ''The Triumph of the Symbol: Pictorial Representation of Deities in Mesopotamia and the Biblical Image Ban'', 2005, Saint-Paul, {{ISBN, 3525530072, 9783525530078google books

*Russell, John M., ''Sennacherib's ‘Palace without Rival’ at Nineveh'', 1991, Chicago * * Hunting in art War art