Assyrian continuity on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern

Ancient

Ancient

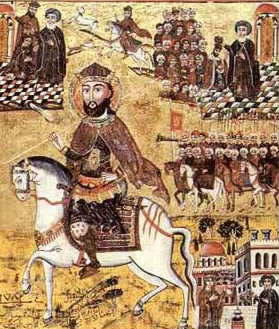

Pre-modern Syriac-language sources at times identified positively with the ancient Assyrians, with the regional population keeping the memory of Assyria alive in the local Syriac histories of the Sasanian period, drawing connections between the ancient empire and themselves. Most prominently, ancient Assyrian kings and figures long appeared in local folklore and literary tradition and claims of descent from ancient Assyrian royalty were forwarded both for figures in folklore and by actual living high-ranking members of society in northern Mesopotamia. Figures like Sargon II, Sennacherib (705–681 BC),

Pre-modern Syriac-language sources at times identified positively with the ancient Assyrians, with the regional population keeping the memory of Assyria alive in the local Syriac histories of the Sasanian period, drawing connections between the ancient empire and themselves. Most prominently, ancient Assyrian kings and figures long appeared in local folklore and literary tradition and claims of descent from ancient Assyrian royalty were forwarded both for figures in folklore and by actual living high-ranking members of society in northern Mesopotamia. Figures like Sargon II, Sennacherib (705–681 BC),  To account for the appearance of Assyrian figures like Sennacherib and Esarhaddon in these Syriac texts, scholars have argued that oral, folkloric memories of the ancient Assyrians continued in regions such as Arbela,

To account for the appearance of Assyrian figures like Sennacherib and Esarhaddon in these Syriac texts, scholars have argued that oral, folkloric memories of the ancient Assyrians continued in regions such as Arbela,  Among West Syrians, the results of the Leiden project have argued that the Syriac Orthodox have been continuously reconstructing their past since their inception as a Christian community in hopes of legitimizing their existence as a distinct group. Before 451 AD, the Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Orthodox did not have the 6 features of an ethnic community as defined by Hutchinson and Smith. Syriac-speaking Miaphysitism, Miaphysites could not claim a myth of common ancestry or even features of a culture and had no proper name to express their community. But even after the Syriac Church became independent, from 451 to the middle of the seventh century, Syriac writers were primarily concerned with validating the status of Syriac Christianity. Only later on during contacts with Islam did the Syriac Christians start to question and define what their identity really was, based on cultural traditions and sources of their time. Language, which was one of the strongest features of communal identity, became very important, but only after some time. A reason why there is a great attachment to Aramaic is that it was considered by Syriac writers to be the divine language, used by Jesus on Earth. As soon as Syriac became a symbol of religious recognition that was becoming an ethnic community, it allowed Syriac Christians to turn to an ancient past in hopes of defining themselves. They reasoned that the Assyrians and Babylonians spoke Syriac, which was Aramaic, and hence they were a part of the Syrian people. This is a process of social identity construction, and one should not think of ancient fault lines here. This idea started as early as Severus Sebokht, who marked astronomy as one of the cornerstones of civilization and who identified the ancient peoples of modern-day

Among West Syrians, the results of the Leiden project have argued that the Syriac Orthodox have been continuously reconstructing their past since their inception as a Christian community in hopes of legitimizing their existence as a distinct group. Before 451 AD, the Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Orthodox did not have the 6 features of an ethnic community as defined by Hutchinson and Smith. Syriac-speaking Miaphysitism, Miaphysites could not claim a myth of common ancestry or even features of a culture and had no proper name to express their community. But even after the Syriac Church became independent, from 451 to the middle of the seventh century, Syriac writers were primarily concerned with validating the status of Syriac Christianity. Only later on during contacts with Islam did the Syriac Christians start to question and define what their identity really was, based on cultural traditions and sources of their time. Language, which was one of the strongest features of communal identity, became very important, but only after some time. A reason why there is a great attachment to Aramaic is that it was considered by Syriac writers to be the divine language, used by Jesus on Earth. As soon as Syriac became a symbol of religious recognition that was becoming an ethnic community, it allowed Syriac Christians to turn to an ancient past in hopes of defining themselves. They reasoned that the Assyrians and Babylonians spoke Syriac, which was Aramaic, and hence they were a part of the Syrian people. This is a process of social identity construction, and one should not think of ancient fault lines here. This idea started as early as Severus Sebokht, who marked astronomy as one of the cornerstones of civilization and who identified the ancient peoples of modern-day

Early travellers and missionaries in northern Mesopotamia in the 19th century observed connections between the indigenous Christian population and the ancient Assyrians. The British traveller Claudius Rich (1787–1821) referenced "Assyrian Christians" in ''Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan and on the site of Ancient Nineveh'' (published posthumously in 1836, though describing an 1820 journey). It is just possible that Rich considered "Assyrian" a geographic, rather than ethnic, term since he in a footnote on the same page also referenced the "Christians of Assyria". More clear-cut evidence of Assyrian self-identity in the 19th century can be seen in the writings of the American missionary Horatio Southgate (1812–1894). In Southgate's ''Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia'' (1844) he remarked with surprise that Armenians referred to the Syriac Christians as ''Assouri'', which Southgate associated with the English "Assyrians", rather than ''Syriani'', which he himself had been using. It seems that the Assyrian identification had been in use for several decades before Layard's excavation, such as in Kharput, but also even the Syriac Orthodox Church in Istanbul, Constantinople bore the name "Assyrian Orthodox" as early as 1844. Early Jacobites found it conventional to use the English "Assyrian" to translate emic ''sūryōyō'' and its equivalents in other languages. Armenian and Georgian sources have since antiquity consistently referred to Assyrians as ''Assouri'' or ''Asori'', and similarly Medieval Arab writers named the Christians of Northern Mesopotamia as "Ashuriyun". Southgate also mentioned that the Syriac Christians themselves at this point claimed origin from the ancient Assyrians as "sons of Assour". Southgate's account thus demonstrates that modern Assyrians still claimed ancient Assyrian descent already in the early 19th century, a period prior to the great archaeological discoveries of the mid to late 19th century. Despite the survival of Assyrian self-ascription among some villages in the Syriac Orthodox heartland, even in areas that had never encountered missionaries or archeologists, the majority identified primarily as ''sūryōye''.

Connections between the modern population and ancient Assyrians were further popularized in the west and academia by the British archaeologist and traveller Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894), responsible for the early excavations of several major ancient Assyrian sites, such as Nimrud. In ''Nineveh and its Remains'' (1849), Layard argued that the Christians he met in northern Mesopotamia and southeast Anatolia claimed to be "descendants of the ancient Assyrians". It is possible that Layard's knowledge of them as such derived from his partnership with the local Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam (1826–1910).

Towards the end of the 19th century, a so-called "religious renaissance" or "awakening" took place in Urmia, Iran. Perhaps partly encouraged by Anglicanism, Anglican, Catholic Church, Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox missionary efforts, the concepts of nation and nationalism were introduced to the Assyrians in Urmia, who began to revive the term ''ʾāthorāyā'' as a self-identity, and began building a national ideology more heavily based around ancient Assyria than Christianity. This was not an isolated phenomenon: Middle Eastern nationalism, probably influenced by developments in Europe, also began to be strongly expressed in other communities during this time, such as among the

Early travellers and missionaries in northern Mesopotamia in the 19th century observed connections between the indigenous Christian population and the ancient Assyrians. The British traveller Claudius Rich (1787–1821) referenced "Assyrian Christians" in ''Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan and on the site of Ancient Nineveh'' (published posthumously in 1836, though describing an 1820 journey). It is just possible that Rich considered "Assyrian" a geographic, rather than ethnic, term since he in a footnote on the same page also referenced the "Christians of Assyria". More clear-cut evidence of Assyrian self-identity in the 19th century can be seen in the writings of the American missionary Horatio Southgate (1812–1894). In Southgate's ''Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia'' (1844) he remarked with surprise that Armenians referred to the Syriac Christians as ''Assouri'', which Southgate associated with the English "Assyrians", rather than ''Syriani'', which he himself had been using. It seems that the Assyrian identification had been in use for several decades before Layard's excavation, such as in Kharput, but also even the Syriac Orthodox Church in Istanbul, Constantinople bore the name "Assyrian Orthodox" as early as 1844. Early Jacobites found it conventional to use the English "Assyrian" to translate emic ''sūryōyō'' and its equivalents in other languages. Armenian and Georgian sources have since antiquity consistently referred to Assyrians as ''Assouri'' or ''Asori'', and similarly Medieval Arab writers named the Christians of Northern Mesopotamia as "Ashuriyun". Southgate also mentioned that the Syriac Christians themselves at this point claimed origin from the ancient Assyrians as "sons of Assour". Southgate's account thus demonstrates that modern Assyrians still claimed ancient Assyrian descent already in the early 19th century, a period prior to the great archaeological discoveries of the mid to late 19th century. Despite the survival of Assyrian self-ascription among some villages in the Syriac Orthodox heartland, even in areas that had never encountered missionaries or archeologists, the majority identified primarily as ''sūryōye''.

Connections between the modern population and ancient Assyrians were further popularized in the west and academia by the British archaeologist and traveller Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894), responsible for the early excavations of several major ancient Assyrian sites, such as Nimrud. In ''Nineveh and its Remains'' (1849), Layard argued that the Christians he met in northern Mesopotamia and southeast Anatolia claimed to be "descendants of the ancient Assyrians". It is possible that Layard's knowledge of them as such derived from his partnership with the local Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam (1826–1910).

Towards the end of the 19th century, a so-called "religious renaissance" or "awakening" took place in Urmia, Iran. Perhaps partly encouraged by Anglicanism, Anglican, Catholic Church, Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox missionary efforts, the concepts of nation and nationalism were introduced to the Assyrians in Urmia, who began to revive the term ''ʾāthorāyā'' as a self-identity, and began building a national ideology more heavily based around ancient Assyria than Christianity. This was not an isolated phenomenon: Middle Eastern nationalism, probably influenced by developments in Europe, also began to be strongly expressed in other communities during this time, such as among the

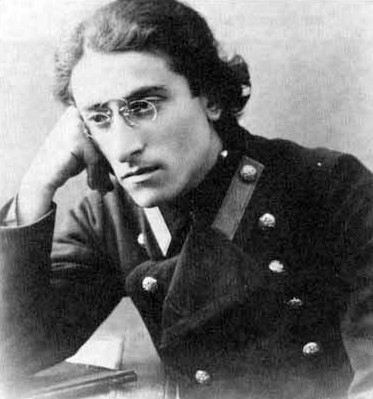

In the years before World War I, several prominent East Aramaic-language authors and intellectuals promoted Assyrian nationalism. Among them were Freydun Atturaya (1891–1926), who in 1911 published an influential article titled ''Who are the Syrians'' [surayē]''? How is Our Nation to Be Raised Up?'', in which he pointed out the connection between ''surayē'' and "Assyrian" and argued for the adoption of ''ʾāthorāyā''. The early 20th century saw an increase in the use of the term ''ʾāthorāyā'' as a self-identity. Also used as the neologism ''ʾasurāyā'', perhaps inspired by the Armenian ''Asori''. The adoption of ''ʾāthorāyā'' and a stronger association with ancient Assyria through nationalism is not a unique development in regard to the Assyrians. Greeks, for instance, due to associating the term "Hellene" with the pagan religion, overwhelmingly self-identified as Rhomioi, Romans (''Rhōmioi'') up until nationalism around the time of the Greek War of Independence, when a more strong association with Ancient Greece spread among the populace. Today, ''sūryōyō'' or ''sūrāyā'' are the predominant self-designations used by Assyrians in their native language, though they are typically translated as "Assyrian" rather than "Syrian".

Today, as a consequence of World War I, the ''Sayfo'' (Assyrian genocide) and various other massacres, a majority of the Assyrians have been displaced from their homeland, and today they live in Assyrian–Chaldean–Syriac diaspora, diaspora communities in Assyrian population by country, countries such as German Assyrians, Germany, Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden, Sweden, Denmark, the British Assyrians, United Kingdom, Assyrians in Greece, Greece, Assyrian Australians, Australia, Assyrians in New Zealand, New Zealand and the Assyrian Americans, United States. In the aftermath of these events, explicit Assyrian self-identity became even more widespread and established in their communities, not only in order to unify communities in the diaspora (which often originated in different regions) but also because "Syrian" became internationally established as the demonym of the newly created country of

In the years before World War I, several prominent East Aramaic-language authors and intellectuals promoted Assyrian nationalism. Among them were Freydun Atturaya (1891–1926), who in 1911 published an influential article titled ''Who are the Syrians'' [surayē]''? How is Our Nation to Be Raised Up?'', in which he pointed out the connection between ''surayē'' and "Assyrian" and argued for the adoption of ''ʾāthorāyā''. The early 20th century saw an increase in the use of the term ''ʾāthorāyā'' as a self-identity. Also used as the neologism ''ʾasurāyā'', perhaps inspired by the Armenian ''Asori''. The adoption of ''ʾāthorāyā'' and a stronger association with ancient Assyria through nationalism is not a unique development in regard to the Assyrians. Greeks, for instance, due to associating the term "Hellene" with the pagan religion, overwhelmingly self-identified as Rhomioi, Romans (''Rhōmioi'') up until nationalism around the time of the Greek War of Independence, when a more strong association with Ancient Greece spread among the populace. Today, ''sūryōyō'' or ''sūrāyā'' are the predominant self-designations used by Assyrians in their native language, though they are typically translated as "Assyrian" rather than "Syrian".

Today, as a consequence of World War I, the ''Sayfo'' (Assyrian genocide) and various other massacres, a majority of the Assyrians have been displaced from their homeland, and today they live in Assyrian–Chaldean–Syriac diaspora, diaspora communities in Assyrian population by country, countries such as German Assyrians, Germany, Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden, Sweden, Denmark, the British Assyrians, United Kingdom, Assyrians in Greece, Greece, Assyrian Australians, Australia, Assyrians in New Zealand, New Zealand and the Assyrian Americans, United States. In the aftermath of these events, explicit Assyrian self-identity became even more widespread and established in their communities, not only in order to unify communities in the diaspora (which often originated in different regions) but also because "Syrian" became internationally established as the demonym of the newly created country of  For communities that identify themselves as Assyrian, Assyrian continuity forms a key part of their self-identity. Many modern Assyrians are named after ancient Mesopotamian figures, such as Sargon of Akkad, Sargon, Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar (and indeed many Assyrian family names still link to ancient Mesopotamian names), and the modern Assyrian flag displays symbolism which is derived from ancient Assyria. From the second half of the 20th century to the present, Assyrians, particularly in the diaspora, have continued to promote Assyrian nationalism as a unifying force among their people. Some denominational groups have opposed being lumped in as "Assyrians" and as a result, they have founded counter-movements of their own; the so-called "name debate" is still a hotly discussed topic within Syriac Christian communities today, especially in the diaspora which lives outside the Assyrian homeland.

Followers of the

For communities that identify themselves as Assyrian, Assyrian continuity forms a key part of their self-identity. Many modern Assyrians are named after ancient Mesopotamian figures, such as Sargon of Akkad, Sargon, Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar (and indeed many Assyrian family names still link to ancient Mesopotamian names), and the modern Assyrian flag displays symbolism which is derived from ancient Assyria. From the second half of the 20th century to the present, Assyrians, particularly in the diaspora, have continued to promote Assyrian nationalism as a unifying force among their people. Some denominational groups have opposed being lumped in as "Assyrians" and as a result, they have founded counter-movements of their own; the so-called "name debate" is still a hotly discussed topic within Syriac Christian communities today, especially in the diaspora which lives outside the Assyrian homeland.

Followers of the

In addition to continuity in self-designation and self-perception, there continued to be important continuities between ancient and contemporary Mesopotamia in terms of religion, literary culture and settlement well after the post-imperial period.

In addition to continuity in self-designation and self-perception, there continued to be important continuities between ancient and contemporary Mesopotamia in terms of religion, literary culture and settlement well after the post-imperial period.

The Fast of Nineveh is a three-day fast commemorating the repentance of the Ninevites at the hands of Jonah and is found in all of the traditional churches of modern Assyrians, such as the

The Fast of Nineveh is a three-day fast commemorating the repentance of the Ninevites at the hands of Jonah and is found in all of the traditional churches of modern Assyrians, such as the

In the wake of the Late Bronze Age collapse around 1200 BC, Arameans, Aramean tribes began to migrate into Assyrian territory. In the first millennium BC, Aramean influence on Assyria grew greater and greater, owing to further migrations as well as mass deportations enacted by several Assyrian kings. Though the expansion of the Assyrian Empire, in combination with resettlements and deportations, changed the ethno-cultural make-up of the Assyrian heartland, there is no evidence to suggest that the more ancient Assyrian inhabitants of the land ever disappeared or became restricted to a small elite, nor that the ethnic and cultural identity of the new settlers was anything other than "Assyrian" after one or two generations.

Because the Assyrians never imposed their language on foreign peoples whose lands they conquered outside of the Assyrian heartland, there were no mechanisms in place to stop the spread of languages other than Akkadian. Beginning with the migrations of Aramaic-speaking settlers into Assyrian territory during the Middle Assyrian period, this lack of linguistic policies facilitated the spread of the Aramaic language. As the most widely spoken and mutually understandable of the Semitic languages (the language group containing many of the languages spoken through the empire), Aramaic grew in importance throughout the Neo-Assyrian period and increasingly replaced the Akkadian language even within the Assyrian heartland itself. From the 9th century BC onwards, Aramaic became the ''de facto'' lingua franca, with Akkadian becoming relegated to a language of the political elite (i.e. governors and officials).

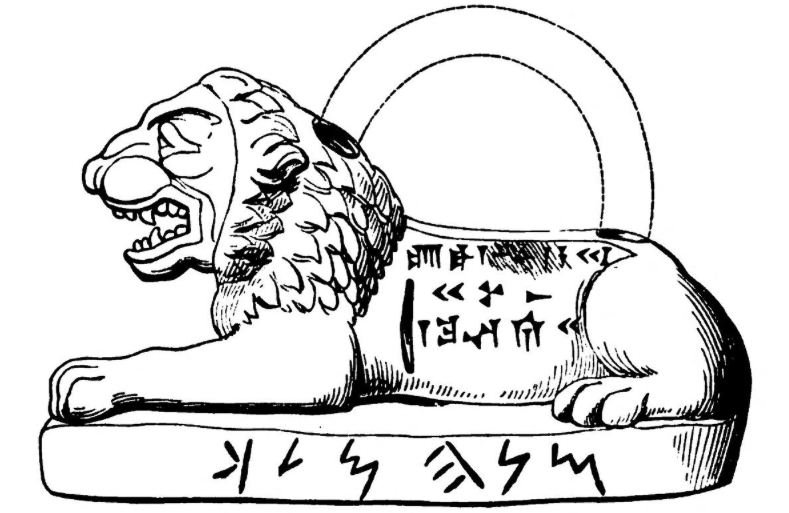

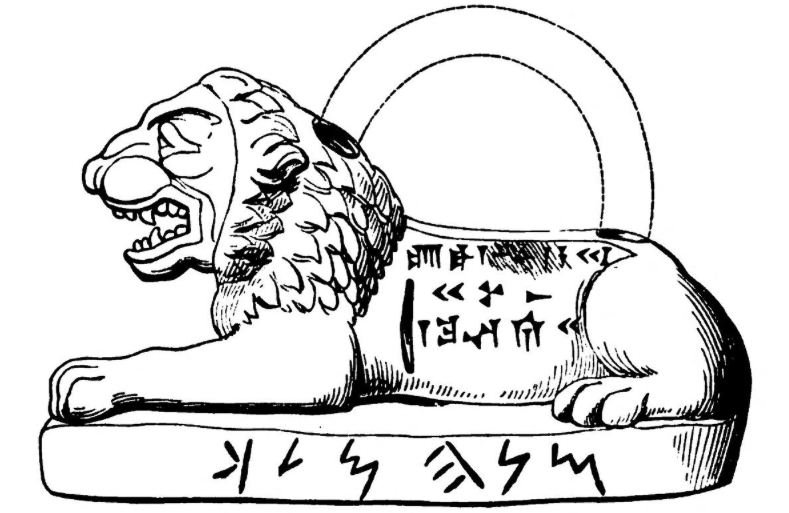

The widespread adoption of the language does not indicate a wholesale replacement of the original native population; the Aramaic language was used not only by settlers but also by native Assyrians, who adopted it and its alphabetic script. The Aramaic language had entered the Assyrian royal administration by the reign of Shalmaneser III (859–824 BC), given that Aramaic writings are known from a palace he built in Nimrud. By the time of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC), the Assyrian kings employed both Akkadian and Aramaic-language royal scribes, confirming the rise of Aramaic to a position of an official language used by the imperial administration. It is clear that Aramaic was spoken by the Assyrian royal family from at least the late 8th century BC onwards, given that Tiglath-Pileser's son Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC) owned a set of Assyrian lion weights, lion weights inscribed with text in both Akkadian and Aramaic. A recorded drop in the number of cuneiform documents late in the reign of Ashurbanipal (669–631 BC) could indicate a greater shift to Aramaic, often written on perishable materials like leather scrolls or papyrus, though it could perhaps alternatively be attributed to political instability in the empire. The denizens of Assur and other former Assyrian population centers under Parthian rule, who clearly connected themselves to ancient Assyria, wrote and spoke Aramaic.

Though modern Assyrian languages, most prominently the Suret language, are Neo-Aramaic languages with little resemblance to the old Akkadian language, they are not wholly without Akkadian influence. Most notably there are numerous examples of Akkadian loanwords in both ancient and modern Aramaic languages. This connection was noted already in 1974, when a study by Stephen A. Kaufman found that the Syriac language, an Aramaic dialect today mainly used liturgical language, has at least fourteen exclusive (i.e. not attested in other dialects) loanwords from Akkadian, including nine of which are clearly from the ancient Assyrian dialect (six of which are architectural or topographical terms). A 2011 study by Kathleen Abraham and Michael Sokoloff on 282 words previously believed to have been Aramaic loanwords in Akkadian determined that many such cases were questionable, and also found that 15 of those words were actually Akkadian loanwords in Aramaic and that the direction of the loan could not be determined in 22 cases; Abraham's and Sokoloff's conclusion was that the number of loanwords from Akkadian to Aramaic was far larger than the number of loanwords from Aramaic to Akkadian. Akkadian is the underlying substrate of multiple modern Syriac phenomena, some of which have managed to survive four-thousand years, and both languages can help to decipher each other in their linguistics at times.

In the wake of the Late Bronze Age collapse around 1200 BC, Arameans, Aramean tribes began to migrate into Assyrian territory. In the first millennium BC, Aramean influence on Assyria grew greater and greater, owing to further migrations as well as mass deportations enacted by several Assyrian kings. Though the expansion of the Assyrian Empire, in combination with resettlements and deportations, changed the ethno-cultural make-up of the Assyrian heartland, there is no evidence to suggest that the more ancient Assyrian inhabitants of the land ever disappeared or became restricted to a small elite, nor that the ethnic and cultural identity of the new settlers was anything other than "Assyrian" after one or two generations.

Because the Assyrians never imposed their language on foreign peoples whose lands they conquered outside of the Assyrian heartland, there were no mechanisms in place to stop the spread of languages other than Akkadian. Beginning with the migrations of Aramaic-speaking settlers into Assyrian territory during the Middle Assyrian period, this lack of linguistic policies facilitated the spread of the Aramaic language. As the most widely spoken and mutually understandable of the Semitic languages (the language group containing many of the languages spoken through the empire), Aramaic grew in importance throughout the Neo-Assyrian period and increasingly replaced the Akkadian language even within the Assyrian heartland itself. From the 9th century BC onwards, Aramaic became the ''de facto'' lingua franca, with Akkadian becoming relegated to a language of the political elite (i.e. governors and officials).

The widespread adoption of the language does not indicate a wholesale replacement of the original native population; the Aramaic language was used not only by settlers but also by native Assyrians, who adopted it and its alphabetic script. The Aramaic language had entered the Assyrian royal administration by the reign of Shalmaneser III (859–824 BC), given that Aramaic writings are known from a palace he built in Nimrud. By the time of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC), the Assyrian kings employed both Akkadian and Aramaic-language royal scribes, confirming the rise of Aramaic to a position of an official language used by the imperial administration. It is clear that Aramaic was spoken by the Assyrian royal family from at least the late 8th century BC onwards, given that Tiglath-Pileser's son Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC) owned a set of Assyrian lion weights, lion weights inscribed with text in both Akkadian and Aramaic. A recorded drop in the number of cuneiform documents late in the reign of Ashurbanipal (669–631 BC) could indicate a greater shift to Aramaic, often written on perishable materials like leather scrolls or papyrus, though it could perhaps alternatively be attributed to political instability in the empire. The denizens of Assur and other former Assyrian population centers under Parthian rule, who clearly connected themselves to ancient Assyria, wrote and spoke Aramaic.

Though modern Assyrian languages, most prominently the Suret language, are Neo-Aramaic languages with little resemblance to the old Akkadian language, they are not wholly without Akkadian influence. Most notably there are numerous examples of Akkadian loanwords in both ancient and modern Aramaic languages. This connection was noted already in 1974, when a study by Stephen A. Kaufman found that the Syriac language, an Aramaic dialect today mainly used liturgical language, has at least fourteen exclusive (i.e. not attested in other dialects) loanwords from Akkadian, including nine of which are clearly from the ancient Assyrian dialect (six of which are architectural or topographical terms). A 2011 study by Kathleen Abraham and Michael Sokoloff on 282 words previously believed to have been Aramaic loanwords in Akkadian determined that many such cases were questionable, and also found that 15 of those words were actually Akkadian loanwords in Aramaic and that the direction of the loan could not be determined in 22 cases; Abraham's and Sokoloff's conclusion was that the number of loanwords from Akkadian to Aramaic was far larger than the number of loanwords from Aramaic to Akkadian. Akkadian is the underlying substrate of multiple modern Syriac phenomena, some of which have managed to survive four-thousand years, and both languages can help to decipher each other in their linguistics at times.

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern Assyrian people

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group Indigenous peoples, indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians Assyrian continuity, share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesop ...

, a recognised Semitic indigenous ethnic

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

, religious, and linguistic minority in Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

(particularly in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, northeast Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, southeast Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, northwest Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and in the Assyrian diaspora

The Assyrian diaspora ( Syriac: ܓܠܘܬܐ, ''Galuta'', "exile") refers to ethnic Assyrians living in communities outside their ancestral homeland. The Eastern Aramaic-speaking Assyrians claim descent from the ancient Assyrians and are one of t ...

) and the people of Ancient Mesopotamia

The Civilization of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writ ...

in general and ancient Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

in particular. Assyrian continuity and Ancient Mesopotamian heritage is a key part of the identity of the modern Assyrian people

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group Indigenous peoples, indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians Assyrian continuity, share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesop ...

. No archaeological, genetic, linguistic, anthropological, or written historical evidence exists of the original Assyrian and Mesopotamian population being exterminated, removed, bred out, or replaced in the aftermath of the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Modern contemporary scholarship "almost unilaterally" supports Assyrian continuity, recognizing the modern Assyrians as the ethnic, historical, and genetic descendants of the East Assyrian-speaking population of Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

specifically, and (alongside the Mandeans) of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

in general, which were composed of both the old native Assyrian population and of neighboring settlers

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

in the Assyrian heartland.

Due to an initial long-standing shortage of historical sources beyond the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

and a handful of inaccurate and contradictory works by a few later classical European authors, many Western historians prior to the early 19th century believed Assyrians (and Babylonians) to have been completely annihilated, although this was never the view in the region of Mesopotamia itself or surrounding regions in West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, where the name of the land continued to be applied until the mid 7th century AD, and Assyrian people have continued to be referenced as such through to the present day.

European writers also often inaccurately equated Assyrians with Nestorians

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinary, doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian t ...

during the Medieval Era, a now unanimously rejected idea that lingered into the early 19th century among some western scholars, despite Assyrian conversion to Christianity preceding Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinary, doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian t ...

by many centuries, and Assyrians being members of churches such as the Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE), sometimes called the Church of the East and officially known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, is an Eastern Christianity, Eastern Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian denomin ...

, Syriac Orthodox Church

The Syriac Orthodox Church (), also informally known as the Jacobite Church, is an Oriental Orthodox Christian denomination, denomination that originates from the Church of Antioch. The church currently has around 4-5 million followers. The ch ...

(and from the 17th century offshoot of the Assyrian Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church

The Chaldean Catholic Church is an Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic Catholic particular churches and liturgical rites, particular church (''sui iuris'') in full communion with the Holy See and the rest of the Catholic Church, and is ...

) which are doctrinally distinct from Nestorianism.

Modern Assyriology

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , ''-logia''), also known as Cuneiform studies or Ancient Near East studies, is the archaeological, anthropological, historical, and linguistic study of the cultures that used cuneiform writing. The fie ...

has increasingly and successfully challenged the initial Western perception; today, Assyriologists, Iranologists and historians recognize that Assyrian culture, identity, and people clearly survived the violent fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and endured into modern times. The last period of ancient Assyrian history is now regarded to be the long post-imperial period from the 6th century BC through to the 7th century AD when Assyria was also known as Athura

Athura ( ''Aθurā'' ), also called Assyria, was a geographical area within the Achaemenid Empire in Upper Mesopotamia from 539 to 330 BC as a military protectorate state. Although sometimes regarded as a satrapy, Achaemenid royal inscriptions ...

, Assyria Provincia and Asoristan, during which the Akkadian language

Akkadian ( ; )John Huehnergard & Christopher Woods, "Akkadian and Eblaite", ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages''. Ed. Roger D. Woodard (2004, Cambridge) Pages 218–280 was an East Semitic language that is attested ...

gradually went extinct by the 1st century AD, but other aspects of Assyrian culture, such as religion, traditions, and naming patterns, and the Akkadian influenced East Aramaic dialects specific to Mesopotamia survived in a reduced but highly recognizable form before giving way to specifically native forms of Eastern Rite Christianity, with the Akkadian influenced Assyrian Aramaic dialects surviving into the present day.Frahm, Eckart (2023). "Assyria's Legacy on the Ground". ''Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire''. Basic Books. p. 353. Boldt, Andreas D. (2017). ''Historical Mechanisms: An Experimental Approach to Applying Scientific Theories to the Study of History''. Taylor & Francis. p. 154.

The gradual extinction of Akkadian and its replacement with Akkadian influenced East Aramaic does not reflect the disappearance of the original Assyrian population; Aramaic was used not only by settlers but was also adopted by native Assyrians and Babylonians, in time even becoming used by the royal administrations of Assyria and Babylonia themselves, and indeed retained by the succeeding Indo-European speaking Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. In fact, the new language of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

, the Imperial Aramaic

Imperial Aramaic is a linguistic term, coined by modern Aramaic studies, scholars in order to designate a specific historical Variety (linguistics), variety of Aramaic language. The term is polysemic, with two distinctive meanings, wider (socioli ...

, was itself a creation of the Assyrian Empire and its people, and with its retention of an Akkadian grammatical structure and Akkadian words and names, is distinct from the Western Aramaic of the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

which gradually replaced the Canaanite languages

The Canaanite languages, sometimes referred to as Canaanite dialects, are one of four subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages. The others are Aramaic and the now-extinct Ugaritic and Amorite language. These closely related languages origin ...

(with the partial exception of Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

). In addition, Aramaic also replaced other Semitic languages such as Hebrew, Phoenician, Arabic, Edomite, Moabite, Amorite, Ugarite, Dilmunite, and Chaldean among non-Aramean peoples without prejudicing their origins and identity. Since the Aramaic language was so deeply integrated into the empire and due to the fact it was spread chiefly by Assyria, in later Demotic Egyptian, Greek, and Mishanic Hebrew texts it was referred to as the "Assyrian writing." Due to assimilation efforts encouraged by Assyrian kings, fellow Semitic Arameans, Israelites, Judeans, Phoenicians, and other non-Semitic groups such as Hittites, Hurrians, Urartians, Phrygians, Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

, and Elamites deported into the Assyrian heartland are also likely to quickly have been absorbed into the native population, self-identified, and been regarded, as Assyrians. The Assyrian population of Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the regio ...

was largely Christianized

Christianization (or Christianisation) is a term for the specific type of change that occurs when someone or something has been or is being converted to Christianity. Christianization has, for the most part, spread through missions by individu ...

between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, however Mesopotamian religion enduring among Assyrians in small pockets until the late Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, a further indication of continuity. Assyrian Aramaic-language sources from the Christian period predominantly use the self-designation ''Suryāyā'' ("Syrian") alongside "Athoraya" and "Asoraya" The term ''Suryāyā'', sometimes alternatively translated as "Syrian" or "Syriac", is generally accepted to derive from the ancient Akkadian ''Assūrāyu'', meaning Assyrian. The academic consensus is that the modern name "Syria" originated as a shortened form of "Assyria" and applied originally only to Mesopotamian Assyria and not to the modern Levantine country of Syria.

Assyrian nationalism

Assyrian nationalism is a movement of the Assyrian people that advocates for Assyrian independence movement, independence or autonomy within the regions they inhabit in northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey. ...

centered on a desire for self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

developed near the end of the 19th century, coinciding with increasing contacts with Europeans, increasing levels of ethnic and religious persecution, along with increased expressions nationalism in other Middle Eastern groups, such as the Arabs, Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

, Copts

Copts (; ) are a Christians, Christian ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligious group native to Northeast Africa who have primarily inhabited the area of modern Egypt since antiquity. They are, like the broader Egyptians, Egyptian population, des ...

, Jews, Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

, Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

, and Turks. Through the large-scale promotion of long extant terms and promotion of identities such as ''ʾĀthorāyā'' and ''ʾAsurāyā'', Assyrian intellectuals and authors hoped to inspire the unification of the Assyrian nation, transcending long-standing religious denominational divisions between the Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East (ACOE), sometimes called the Church of the East and officially known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, is an Eastern Christianity, Eastern Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian denomin ...

, its 17th century offshoot, the Chaldean Catholic Church

The Chaldean Catholic Church is an Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic Catholic particular churches and liturgical rites, particular church (''sui iuris'') in full communion with the Holy See and the rest of the Catholic Church, and is ...

, the Syriac Orthodox Church

The Syriac Orthodox Church (), also informally known as the Jacobite Church, is an Oriental Orthodox Christian denomination, denomination that originates from the Church of Antioch. The church currently has around 4-5 million followers. The ch ...

, and various smaller largely Protestant denominations. This effort has been met with both support and some opposition from various religious communities; some denominations have rejected unity and promoted alternate religious identities, such as "Aramean

The Arameans, or Aramaeans (; ; , ), were a tribal Semitic people in the ancient Near East, first documented in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. Their homeland, often referred to as the land of Aram, originally covered ce ...

", " Syriac", and " Chaldean". Though some religious officials and activists (particularly in the west) have promoted such identities as separate ethnic groups rather than simply religious denominational groups, they are not generally treated as such by international organizations or historians, and historically, genetically, geographically and linguistically these are all the same Assyrian people

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group Indigenous peoples, indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians Assyrian continuity, share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesop ...

.

Assyrians after the Assyrian Empire

Early assumption of Assyrian annihilation

Ancient

Ancient Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

fell in the late 7th century BC through the Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire

The Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire was the last war fought by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, between 626 and 609 BC. Succeeding his brother Ashur-etil-ilani (631–627 BC), the new king of Assyria, Sinsharishkun (627–612 BC), imme ...

, with most of its major population centers violently sacked and most of its territory incorporated into the fellow Mesopotamian Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC a ...

. In the millennia following the fall of Assyria, knowledge of the ancient empire chiefly survived in western literary tradition through accounts of Assyria in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' apocryphal Apocrypha () are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of scripture, some of which might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity. In Christianity, the word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to ...

. '' apocryphal Apocrypha () are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of scripture, some of which might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity. In Christianity, the word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to ...

Book of Judith

The Book of Judith is a deuterocanonical book included in the Septuagint and the Catholic Church, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Christian Old Testament of the Bible but Development of the Hebrew Bible canon, excluded from the ...

states that the Neo-Babylonian

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC ...

king Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II, also Nebuchadrezzar II, meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir", was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Often titled Nebuchadnezzar ...

(605–562 BC) "ruled over the Assyrians in the great city of Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

", the Book of Ezra

The Book of Ezra is a book of the Hebrew Bible which formerly included the Book of Nehemiah in a single book, commonly distinguished in scholarship as Ezra–Nehemiah. The two became separated with the first printed Mikraot Gedolot, rabbinic bib ...

refers to the Persian king Darius I

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

as "king of Assyria", and the Book of Isaiah

The Book of Isaiah ( ) is the first of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible and the first of the Major Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. It is identified by a superscription as the words of the 8th-century BC prophet Isaiah ben Amo ...

states that there will come a day when God will proclaim "Blessed be Egypt my people, and Assyria the work of my hands, and Israel my heritage". The erroneous idea of complete Assyrian annihilation, despite increasing evidence to the contrary, proved to be enduring in western academia. As late as 1925, the Assyriologist Sidney Smith wrote that "The disappearance of the Assyrian people will always remain a unique and striking phenomenon in ancient history. Other, similar kingdoms and empires have indeed passed away, but the people have lived on ... No other land seems to have been sacked and pillaged so completely as was Assyria". Just a year later, Smith had completely abandoned the idea of the Assyrians having been eradicated and recognized the persistence of Assyrians through the Christian period into the present.

Post-imperial Assyria in modern Assyriology

Modern Assyriology does not support the idea that the fall of Assyria also brought with it an eradication of the Assyrian people and their culture. Though in the past regarded as a "post-Assyrian" age, Assyriologists today consider the last period of ancient Assyrian history to be the long post-imperial period, extending from 609 BC to around AD 250 with the destruction of the semi-independent Assyrian states ofAssur

Aššur (; AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; ''Āšūr''; ''Aθur'', ''Āšūr''; ', ), also known as Ashur and Qal'at Sherqat, was the capital of the Old Assyrian city-state (2025–1364 BC), the Midd ...

, Osroene

Osroene or Osrhoene (; ) was an ancient kingdom and region in Upper Mesopotamia. The ''Kingdom of Osroene'', also known as the "Kingdom of Edessa" ( / "Kingdom of Urhay"), according to the name of its capital city (now Urfa, Şanlıurfa, Turkey), ...

, Adiabene

Adiabene ( Greek: Αδιαβηνή, ) was an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, corresponding to the northwestern part of ancient Assyria. The size of the kingdom varied over time; initially encompassing an area between the Zab Rivers, it ...

, Beth Nuhadra and Beth Garmai

Beth Garmai, (, Middle Persian: ''Garamig''/''Garamīkān''/''Garmagān'', New Persian: ''Garmakan'', Kurdish: ''Germiyan/گەرمیان'', , Latin and Greek: ''Garamaea'') is a historical Assyrian region around the city of Kirkuk in northern ...

by the Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranians"), was an Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, the length of the Sasanian dynasty's reign ...

, or to the end of Sassanid ruled Asoristan (Assyria) and the Islamic Conquest around 637 AD, and support a continuity into the present day.

Though the centuries that followed the fall of Assyria are characterized by a distinct lack of surviving sources from the region, at least in comparison to previous eras, the idea that Assyria was rendered uninhabited and desolated stems from the contrast with the richly attested Neo-Assyrian period, not from the actual extant written sources from the post-imperial period, which although reduced, remain unbroken through to the modern era.

Though the Assyrian bureaucracy and governmental institutions disappeared with Assyria's fall, Assyrian population centers and culture did not. At Dur-Katlimmu, one of the largest settlements along the Khabur river, a large Assyrian palace, dubbed the "Red House" by archaeologists, continued to be used in Neo-Babylonian times, with cuneiform records there being written by people with Assyrian names, in Assyrian style, though dated to the reigns of the early Neo-Babylonian kings. These documents mention officials with Assyrian titles and invoke the ancient Assyrian national deity Ashur. Two Neo-Babylonian texts discovered at the city of Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , Zimbir) (also Sippir or Sippara) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its ''Tell (archaeology), tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell ...

in Babylonia attest to there being royally appointed governors at both Assur

Aššur (; AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; ''Āšūr''; ''Aθur'', ''Āšūr''; ', ), also known as Ashur and Qal'at Sherqat, was the capital of the Old Assyrian city-state (2025–1364 BC), the Midd ...

and Guzana

Tell Halaf () is an archaeological site in Al-Hasakah in northeastern Syria, a few kilometers from the city of Ras al-Ayn near the Syria–Turkey border. The site, which dates to the sixth millennium BCE, was the first to be excavated from a ...

, another Assyrian site in the north. Arbela is attested as a thriving Assyrian city, but only very late in the Neo-Babylonian period, and there were attempts to revive the city of Arrapha in reign of Neriglissar (560–556 BC), who returned a cult statue to the site. Harran

Harran is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Şanlıurfa Province, Turkey. Its area is 904 km2, and its population is 96,072 (2022). It is approximately southeast of Urfa and from the Syrian border crossing at Akçakale.

...

was revitalized, with its great temple dedicated to the lunar god Sîn being rebuilt under Nabonidus

Nabonidus (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-naʾid'', meaning "May Nabu be exalted" or "Nabu is praised") was the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 556 BC to the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenian Empire under Cyrus the Great in 53 ...

whose mother was an Assyrian priestess from that city. (556–539 BC). In nearby Edessa

Edessa (; ) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now Urfa or Şanlıurfa, Turkey. It was founded during the Hellenistic period by Macedonian general and self proclaimed king Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Sel ...

, Assyrian religious traditions also survived well into the common era.

Individuals with Assyrian names are attested at multiple sites in Assyria and Babylonia during the Neo-Babylonian Empire, including Babylon, Nippur

Nippur (Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''Nibru'', often logogram, logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"I. E. S. Edwards, C. J. Gadd, N. G. L. Hammond, ''The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory'': Vol. 1, Part 1, Ca ...

, Uruk

Uruk, the archeological site known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river in Muthanna Governorate, Iraq. The site lies 93 kilo ...

, Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , Zimbir) (also Sippir or Sippara) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its ''Tell (archaeology), tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell ...

, Dilbat

Dilbat (modern Tell ed-Duleim or Tell al-Deylam) was an ancient Near Eastern city located 25 kilometers south of Babylon on the eastern bank of the Western Euphrates in modern-day Babil Governorate, Iraq. It lies 15 kilometers southeast of the an ...

and Borsippa

Borsippa (Sumerian language, Sumerian: BAD.SI.(A).AB.BAKI or Birs Nimrud, having been identified with Nimrod) is an archeological site in Babylon Governorate, Iraq, built on both sides of a lake about southwest of Babylon on the east bank of th ...

. The Assyrians in Uruk apparently continued to exist as a community until the reign of the Achaemenid king Cambyses II

Cambyses II () was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning 530 to 522 BCE. He was the son of and successor to Cyrus the Great (); his mother was Cassandane. His relatively brief reign was marked by his conquests in North Afric ...

(530–522 BC) and were closely linked to a local cult dedicated to Ashur. Many individuals with clearly Assyrian names are also known from the rule of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

, sometimes in high levels of government. A prominent example is Pan-Ashur-lumur, who served as the secretary of Cambyses II

Cambyses II () was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning 530 to 522 BCE. He was the son of and successor to Cyrus the Great (); his mother was Cassandane. His relatively brief reign was marked by his conquests in North Afric ...

. The temple dedicated to Ashur in Assur was rebuilt by local Assyrians in the reign of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

. Assyria was powerful enough to rebel twice against the Achaemenid Empire during the late 6th century BC, Assyrian troops provided heavy infantry and archers in the Achaemenid army, Assyrian agriculture provided a breadbasket for the empire and the Imperial Aramaic of the Assyrian Empire was continued by the Achaemenid Empire.

Under the Seleucid and Parthian empires, further efforts were made to revitalize Assyria and the ancient great cities began to be resettled, with the predominant portion of the population remaining native Assyrian. The original Assyrian capital of Assur is in particular known to have flourished during the Parthian era. Continuity from ancient Assyria is clear in Assur and other cities such as Arbela during this period, with personal names of the city's denizens greatly reflecting names used in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, such as ''Qib-Assor'' ("command of Ashur"), ''Assor-tares'' ("Ashur judges") and even ''Assor-heden'' ("Ashur has given a brother", a late version of the name ''Aššur-aḫu-iddina'', i.e. Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (, also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 to 669 BC. The third king of the S ...

), reflecting names extant in the lafe 3rd millennium BC. The Assyrians at Assur continued to follow the traditional ancient Mesopotamian religion

Ancient Mesopotamian religion encompasses the religious beliefs (concerning the gods, creation and the cosmos, the origin of man, and so forth) and practices of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and B ...

, worshipping Ashur (at this time known as ''Assor'') and other Mesopotamian gods such as Shamash, Ishtar, Sin, Adad, Bel, Nergal, Ninurta and Tammuz. Assur may even have been the capital of its own semi-autonomous or vassal state, either under the suzerainty of the largely Assyrian populated Kingdom of Hatra, or under direct Parthian suzerainty. Though this second golden age of Assur came to an end with the conquest, sack and destruction of the city by the Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

AD 240–250, the inscriptions, temples, continued celebration of festivals and the wealth of theophoric elements (divine names) in personal names of the Parthian period illustrate a strong continuity of traditions dating back to circa 21st century BC, and that the most important deities of old Assyria were still worshipped at Assur and elsewhere more than 800 years after the Assyrian Empire had been destroyed.

Identity in ancient Assyria

Development and distinctions

Ethnicity

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they Collective consciousness, collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, ...

and culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

are largely based in self-perception and self-designation. In ancient Assyria, a distinct Assyrian identity appears to have formed already in the Old Assyrian period

The Old Assyrian period was the second stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of the city of Assur from its rise as an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I 2025 BC to the foundation of a larger Assyrian territorial state after th ...

( 2025–1364 BC), when distinctly Assyrian burial practices, foods and dress codes are attested and Assyrian documents appear to consider the inhabitants of Assur to be a distinct cultural group, even though they were ethnolinguistically identical to the Semites of Southern Mesopotamia (Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

). A wider Assyrian identity appears to have spread across northern Mesopotamia under the Middle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. ...

( 1363–912 BC), since later writings concerning the reconquests of the early Neo-Assyrian kings refer to some of their wars as liberating the Assyrian people of the cities they reconquered. Though there for much of ancient Assyria's history existed a distinct Assyrian identity, Assyrian culture and civilization, like any other culture and civilization, did not develop in isolation. As the Assyrian Empire expanded and contracted, elements from regions the Assyrians conquered or traded with culturally influenced the Assyrian heartland and the Assyrians themselves. Early Assyrian culture was greatly influenced by the Hurrians

The Hurrians (; ; also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri) were a people who inhabited the Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age. They spoke the Hurrian language, and lived throughout northern Syria, upper Mesopotamia and southeaste ...

and vice versa, a people that also lived in northern Mesopotamia, and by the culture of southern Mesopotamia, particularly that of Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

and Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

.

Surviving evidence suggests that the ancient Assyrians had a relatively open definition of what it meant to be Assyrian. Modern ideas such as a person's ethnic background, or the Roman idea of legal citizenship, do not appear to have been reflected in ancient Assyria. Although Assyrian accounts and artwork of warfare frequently describe and depict foreign enemies, they are not usually depicted with different physical features, but rather with different clothing and equipment, though this may be more related to the fact Assyria mostly had contact with other societies in Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, East Mediterranean, North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and Southern Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and West Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Armenia, ...

where the people were likely similar physically to the Assyrians. Assyrian accounts describe enemies as barbaric

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, Savage (pejorative term), savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prej ...

only in terms of their behaviour, as lacking correct religious practices or being uncivilised, and as doing wrongdoings against Assyria. All things considered, there does not appear to have been any well-developed concepts of ethnicity or race in ancient Assyria. What mattered for a person to be seen by others as Assyrian was mainly fulfillment of obligations (such as military service), being affiliated with the Assyrian Empire politically, and maintaining loyalty to the Assyrian king; some kings, such as Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

(722–705 BC), explicitly encouraged assimilation and mixture of foreign cultures with that of Assyria.

Pre-modern self-identities

Though many foreign states ruled over the Assyrian heartland in the millennia following the empire's fall, there is no evidence of any large scale influx of immigrants that replaced the original population, which instead continued to make up a significant portion of the region's people untilMongol

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China (Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family of M ...

and Timurid massacres in the late 14th century. In pre-modern ecclesiastical Syriac-language (the type of Aramaic used in Christian Mesopotamian writings) sources, the typical self-designations used is suryāyā (as well as the shortened surayā), and sometimes ʾāthorāyā ("Assyrian") and ʾārāmāyā ("Aramaic" or "Aramean"). A reluctance of the overall Christian population to adopt ʾĀthorāyā as a self-designation probably derives from Assyria's portrayal in the Bible. "Assyrian" (Āthorāyā) also continuously survived as the designation for a Christian from Mosul (ancient Nineveh) and Mesopotamia in general. It is clear from the surviving sources that ''ʾārāmāyā'' and ''suryāyā'' were not distinct and mutually exclusive identities, but rather interchangeable terms used to refer to the same people; the Syriac author Bardaisan

Bardaisan (11 July 154 – 222 AD; , ''Bar Dayṣān''; also Bardaiṣan), known in Arabic as ibn Dayṣān () and in Latin as Bardesanes, was a Syriac-speaking Prods Oktor Skjaervo. ''Bardesanes''. Encyclopædia Iranica. Volume III. Fasc. 7-8. . ...

(154–222) is for instance referred to in 4th-century Syriac translations of Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

's ''Church History

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual side of t ...

'' as both ''ārāmāyā'' and ''suryāyā''.

''Suryāyā'', which also occurs in the forms ''suryāyē'' and ''sūrōyē'', though sometimes translated to "Syrian", is believed to derive from the ancient Akkadian term ''assūrāyu'' ("Assyrian"), which was sometimes even in ancient times rendered in the shorter form ''sūrāyu''. Luwian

Luwian (), sometimes known as Luvian or Luish, is an ancient language, or group of languages, within the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. The ethnonym Luwian comes from ''Luwiya'' (also spelled ''Luwia'' or ''Luvia'') – ...

and Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

texts from the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, such as the Çineköy inscription, sometimes use the shortened "Syria" for the Assyrian Empire. The consensus in modern academia is thus that "Syria" is simply a shortened form of "Assyria". The modern distinction between "Assyrian" and "Syrian" is the result of ancient Greek historians and cartographers, who designated the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

as "Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

" and Mesopotamia as "Assyria". By the time the terms are first attested in Greek texts (in the 4th century BC), the local denizens in both the Levant and Mesopotamia had already long used both terms interchangeably for the entire region, and continued to do so well into the later Christian period. Whether the Greeks began referring to Mesopotamia as "Assyria" because they equated the region with the Assyrian Empire, long fallen by the time the term is first attested in Greek, or because they named the region after the people who lived there, the , is not known. It is known however, the Seleucid Greeks conceived that the Aramaic-speakers of the east were descended from the ancient Assyrians, an idea which the Seleucids borrowed from Classical Greeks, who deemed Assyrians and Syrians to be identical. Although the term "Syria" began to be confined to the region west of the Euphrates, the conflation of "Assyrian" and "Syrian" persisted, which is evident among certain communities well into the late medieval period. Even Josephus the Hebrew, who had a more unique stance on Syrian identity, perpetuated the traditions of Strabo and Herodotus which held Assyrians and Syrians to consisted of the same ethnos, mentioning the "Syrians" in Babylonia. This region was once under Assyria, and therefore Josephus followed the reasoning of Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, who argued that its inhabitants could be called "Assyrians" or "Syrians" interchangeably. Syrians in Roman Syria

Roman Syria was an early Roman province annexed to the Roman Republic in 64 BC by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War following the defeat of King of Armenia Tigranes the Great, who had become the protector of the Hellenistic kingdom of Syria.

...

could also posit themselves as constituting the same ethnic group and heirs of an ancient legacy that their counterparts, the Assyrians in the Parthian and Sasanian kingdoms, claimed. Thus, those inhabiting Roman Syria could still envision the ancient Assyrians as their direct ethnic ancestors or at least the founders of their ethnos. In general, Syrians themselves adopted the Greek formulations that conceived of the Aramaic-speakers of the Near East as being descended from the Assyrians and understood their past through it. In doing so, they came to see themselves as an ethnic group. Hence, from the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, authors from Roman Syro-Mesopotamia, such as Tatian

Tatian of Adiabene, or Tatian the Syrian or Tatian the Assyrian, (; ; ; ; – ) was an Assyrian Christian writer and theologian of the 2nd century.

Tatian's most influential work is the Diatessaron, a Biblical paraphrase, or "harmony", of the ...

and Lucian

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridi ...

, writing in Greek and Aramaic, extensively used the Assyrian past to define their communities in relation to the Greeks and Romans and bore their self-ascriptions as "Syrian" and "Assyrian" with significance. Furthermore, although the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, ...

emphasized their Macedonian origins and implemented a policy of Hellenization upon the inhabitants of the Near East whom they ruled over, they eventually began to assimilate into the native Assyrian population of Mesopotamia and adopt their customs, coming to be seen by their contemporaries and even themselves as the heirs of the Neo-Assyrian empire and dynasty. The (As)Syrians too came to see the Seleucids as the successors of Assyria, counting them in continuity with Semiramis

Semiramis (; ''Šammīrām'', ''Šamiram'', , ''Samīrāmīs'') was the legendary Lydian- Babylonian wife of Onnes and of Ninus, who succeeded the latter on the throne of Assyria, according to Movses Khorenatsi. Legends narrated by Diodorus ...

and Sardanapalus, thereby Assyrianizing them. The Roman historian Titus Livius

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

particularly captures this process of Greek assimilation into the native populations when he laments that the Macedonians who settled within Mesopotamia have "degenerated into Syrians".