Assise Sur La Ligece on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Assise sur la ligece'' (roughly, "

The situation evolved in the second quarter of the century with the establishment of baronial dynasties. Magnates—such as

The situation evolved in the second quarter of the century with the establishment of baronial dynasties. Magnates—such as

Before the defeat at Hattin in 1187, the laws developed by the court were documented as in ''Letters of the Holy Sepulchre''. After Hattin, the Franks lost their cities, lands and churches. Many barons fled to Cyprus and intermarried with leading new emigres from the

Assize

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

on liege-homage") is an important piece of legislation passed by the Haute Cour (High Court) of Jerusalem, the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

court of the crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

r Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1 ...

, in an unknown year but probably in the 1170s under Amalric I of Jerusalem.

The ''Assise'' formally prohibited the illegal confiscation of fiefs

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal allegi ...

and required all the king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

's vassals

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

to ally against any lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

who did so. Such a lord would not be tried, but would be stripped of his land or exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

d instead. The king could now legally confiscate a fief if a vassal refused to pay homage to him; this had been done in the past but was technically illegal before this ''Assise''. Apparently the ''Assise'' was created after a dispute between Gerard, Lord of Sidon

The Lordship of Sidon (), later County of Sidon, was one of the four major fiefdoms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem,According to the 13th-century writer John of Ibelin one of the Crusader States. However, in reality, it appears to have been much sm ...

, and King Amalric; Gerard had dispossessed one of his rear-vassals and refused to return the land even when Amalric stepped in. Open warfare was just barely avoided.

The ''Assise'' also made all nobles direct vassals of the king, eliminating the previous distinction between higher and lesser nobles. This distinction still existed in reality, and although they theoretically had an equal voice in the ''Haute Cour'', lesser nobles could only appeal to the high court when their own baronial courts refused to hear their complaints. In any case, the more powerful barons refused to be tried by lesser lords who were not their peers, and the higher nobles could still judge the less powerful lords themselves. There were about 600 men eligible to vote in the Court according to the ''Assise''.

Usage

During the period of near constant warfare in the early decades of the 12thcentury, the king of Jerusalem's foremost role was as leader of the feudal host. They rarely awarded land or lordships, and those they did that became vacant—a frequent event because of the high mortality rate in the conflict—reverted to the crown. Instead, their followers' loyalty was rewarded with city incomes. As a result, the royal domain of the first five rulers—including much ofJudea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

, Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, the coast from Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

to Ascalon

Ascalon or Ashkelon was an ancient Near East port city on the Mediterranean coast of the southern Levant of high historical and archaeological significance. Its remains are located in the archaeological site of Tel Ashkelon, within the city limi ...

, the ports of Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

and Tyre, and other scattered castles and territories—was larger than the combined holdings of the nobility. This meant the rulers of Jerusalem had greater internal power than comparative western monarchs, although they did not have the administrative systems and personnel to govern such a large realm.

The situation evolved in the second quarter of the century with the establishment of baronial dynasties. Magnates—such as

The situation evolved in the second quarter of the century with the establishment of baronial dynasties. Magnates—such as Raynald of Châtillon

Raynald of Châtillon ( 11244 July 1187), also known as Reynald, Reginald, or Renaud, was Prince of Antioch—a crusader states, crusader state in the Middle East—from 1153 to 1160 or 1161, and Lord of Oultrejordain—a Vassals of the Kingdo ...

, Lord of Oultrejordain

The Lordship of Transjordan () was one of the principal lordships of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. It encompassed an extensive and partly undefined region to the east of the Jordan River, and was centered on the castles of Montreal and Kerak.

Ge ...

, and Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, Prince of Galilee

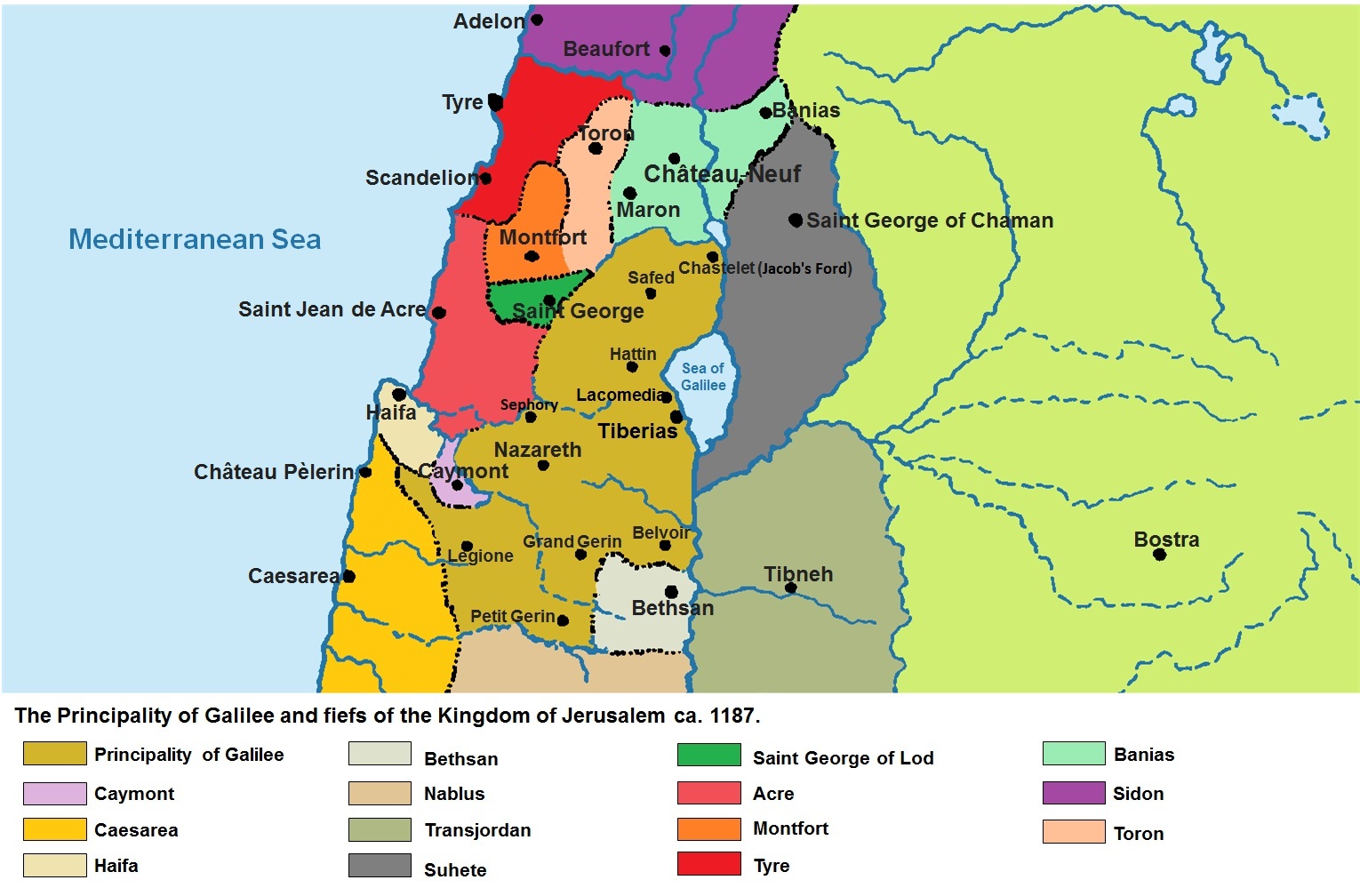

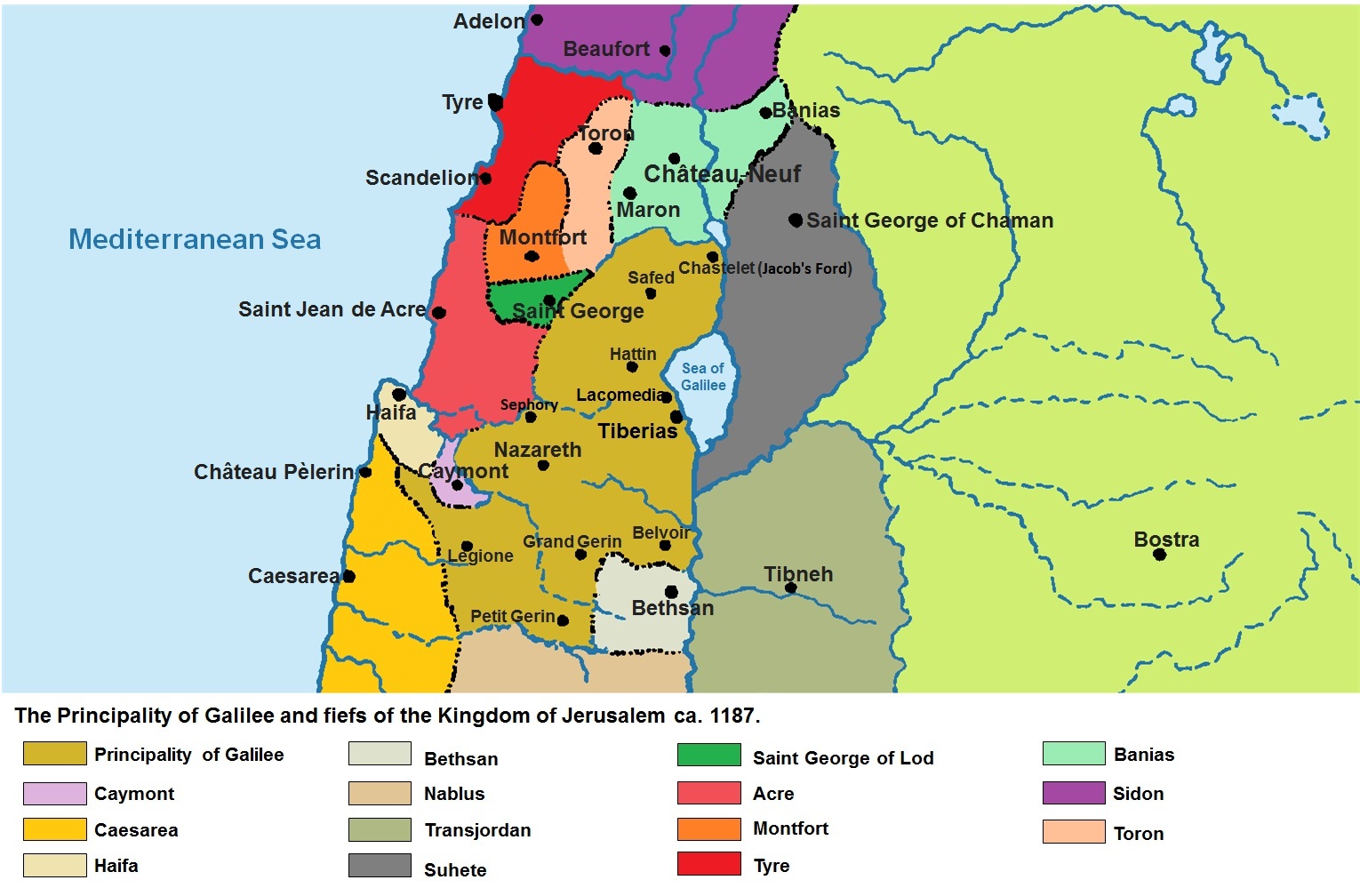

The principality of Galilee was one of the four major seigneuries of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, according to 13th-century commentator John of Ibelin, grandson of Balian. The direct holdings of the principality centred around Tiberias, ...

—often acted as autonomous rulers. Royal powers were abrogated, and governance was undertaken effectively within the feudatories. What central control remained was exercised at the —High Court, in English. Only the 13th-century jurists

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a legal practition ...

of Jerusalem used this term, was more common in Europe. These were meetings between the king and his tenants in chief. Over time, the duty of the vassal to give counsel developed into a privilege and ultimately the legitimacy of the monarch depended on the agreement of the court. In practice, the High Court comprised the great barons and the king's direct vassals. In law, a quorum was the king and three tenants-in-chief

In medieval and early modern Europe, a tenant-in-chief (or vassal-in-chief) was a person who held his lands under various forms of feudal land tenure directly from the king or territorial prince to whom he did homage, as opposed to holding them ...

. The 1162 the theoretically expanded the court's membership to all 600 or more fief-holders, making them all peers. All those who paid homage directly to the king were now members of the of Jerusalem. The heads of the military orders joined them by the end of the 12thcentury, and the Italian communes in the 13thcentury. The leaders of the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

ignored the monarchy of Jerusalem; the kings of England and France agreed on the division of future conquests as if there was no need to take into account the nobility of the crusader states. Joshua Prawer considered the rapid offering of the throne to Conrad of Montferrat in 1190 and then Henry II, Count of Champagne in 1192, demonstrated the weakness of the crown of Jerusalem. This was given legal effect by Baldwin IV's will stipulating if Baldwin V died a minor, the Pope, the kings of England and France, and the Holy Roman Emperor should select the successor.Before the defeat at Hattin in 1187, the laws developed by the court were documented as in ''Letters of the Holy Sepulchre''. After Hattin, the Franks lost their cities, lands and churches. Many barons fled to Cyprus and intermarried with leading new emigres from the

Lusignan

The House of Lusignan ( ; ) was a royal house of French origin, which at various times ruled several principalities in Europe and the Levant, including the kingdoms of Jerusalem, Cyprus, and Armenia, from the 12th through the 15th centuries du ...

, Montbéliard

Montbéliard (; traditional ) is a town in the Doubs department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in eastern France, about from the border with Switzerland. It is one of the two subprefectures of the department.

History

Montbéliard is ...

, Brienne

The County of Brienne was a medieval county in France centered on Brienne-le-Château.

Counts of Brienne

* Engelbert I (c. 950 – c. 968)

* Engelbert II (c. 968 – c. 990)

* Engelbert III (c. 990 – c. 1008)

* Engelbert IV (c. 10 ...

and Montfort families. This created a class apart from the remnants of the old nobility with limited understanding of the Latin East including the king-consorts Guy, Conrad, Henry, Aimery, John and the absent Hohenstaufen that followed. The entire body of written law was lost in the subsequent fall of Jerusalem. From this point, the legal system was based largely on custom and the memory of the lost legislation. The renowned jurist Philip of Novara

Philip of Novara (c. 1200 – c. 1270) was a medieval historian, warrior, musician, diplomat, poet, and lawyer born at Novara, Italy, into a noble house, who spent his entire adult life in the Middle East. He primarily served the Ibelin family ...

lamented:We know he lawsrather poorly, for they are known by hearsay and usage...and we think an assize is something we have seen as an assize...in the kingdom of Jerusalem he baronsmade much better use of the laws and acted on them more surely before the land was lost.Thus, a myth was created of an idyllic early 12th-century legal system. The barons used this to reinterpret the , which Almalric I intended to strengthen the crown, to constrain the monarch instead, particularly regarding their right to remove feudal fiefs without trial. The concomitant loss of the vast majority of rural fiefs led to the barons becoming an urban mercantile class where knowledge of the law was a valuable, well-regarded skill and a career path to higher status. The barons of Jerusalem in the 13thcentury have been poorly regarded by both contemporary and modern commentators: their superficial rhetoric disgusted James of Vitry; Riley-Smith writes of their pedantry and the use of spurious legal justification for political action. For the barons themselves, it was this ability to articulate the law that was so prized. The sources of this are the elaborate and impressive treatises by the great baronial jurists from the second half of the 13thcentury. The Barons invoked the three times in justification of open opposition to arbitrary acts by the king: in 1198, 1229 and 1232. Ralph of Tiberias set the precedent when he was accused of attempted

regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

. King Aimery had narrowly survived an attempted murder by four armed members of the German Crusade in Tyre. While recovering he became convinced that Ralph was responsible. At a meeting of the High Court, Aimery exiled him, ordering his departure from the kingdom within eight days. In response, Ralph devised a defence based on an interpretation of the . The defence was it was an absolute necessity that a case concerning the relationship between a lord and his vassal was judged in court, that vassals were peers bound to give mutual assistance and that vassals should withdraw service from a lord who refused to submit to the court's decision. Ralph's innovation was applying the assise to the king himself. Aimery refused. His vassals withdrew service from him until 1200 following ''great words'', but Ralph still went into banishment. He only returned in 1207 after the king's death. In the later accounts of the jurists, Ralph was credited with a great achievement. He set a precedent in applying the assise to the actions of the crown. This provided him and his peers with justification, a method of resistance and sanctions that could be legally applied. At the same time, it is clear that the use of the was ineffective. Aimery's refusal meant Ralph had still found it necessary to leave the country.

The second time the precedent was followed consciously happened in 1228 after the arrival in the kingdom of Emperor Frederick II. Three years earlier, he had become king-consort when he married Isabella II and immediately claimed the throne of Jerusalem from her father, the king-regent, John of Brienne

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was the king of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of Erard II of Brienne, a wealthy nobleman in Cham ...

. Isabella died in the summer of that year, after giving birth to a son. The son, Conrad

Conrad may refer to:

People

* Conrad (name)

* Saint Conrad (disambiguation)

Places

United States

* Conrad, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Conrad, Iowa, a city

* Conrad, Montana, a city

* Conrad Glacier, Washington

Elsewher ...

, was through his mother, the king of Jerusalem. As a result, on his arrival Frederick was received as regent. In 1229, Frederick successfully negotiated the return of Jerusalem, lost in 1187 from Egypt, and ''went under the imperial crown in the Holy Sepulchre''. Perhaps in a fit of hubris following the acquisition of the city, according to the later baronial jurists, he instructed his bailli

A bailiff (, ) was the king's administrative representative during the ''ancien régime'' in northern France, where the bailiff was responsible for the application of justice and control of the administration and local finances in his bailiwick ...

Balian Grenier

Balian I Grenier was the count of Sidon and one of the most important lords of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1202 to 1241. He succeeded his father Renaud. His mother was Helvis, a daughter of Balian of Ibelin. He was a powerful and important ...

to take control of the Acre possessions of John of Beirut, Walter I Grenier, Walter III of Caesarea, John of Jaffa, Robert of Haifa, Phillip l'asne and John Moriau. These barons invoked the and their combined force restored their possessions. According to a surviving charter, Alice of Armenia

Alice of Armenia (1182 – after 1234) was ruling Lady of Toron from 1229 to 1234 as the eldest daughter of Ruben III, Prince of Armenia and his wife Isabella of Toron. She was heiress of Toron as well as a claimant to the throne of Armenia. ...

took the same approach to claim the lordship of Toron

Toron, now Tibnin or Tebnine in southern Lebanon, was a major Crusader castle, built in the Lebanon mountains on the road from Tyre to Damascus. The castle was the centre of the Lordship of Toron, a seigneury within the Kingdom of Jerusa ...

. Frederick had awarded this to the Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem on its recovery. After this was decided in Alice's favour, a clear baronial victory, the Barons re-entered the Emperor's service. This was the high point of the vassals ability to use the law to resist a monarch infringing what they believed to be their rights. From May 1229, when Frederick II left the Holy Land to defend his Italian and German lands, monarchs were absent—Conrad from 1225 until 1254 and his son Conradin

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called ''the Younger'' or ''the Boy'', but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (, ), was the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. He was Duke of Swabia (1254–1268) and nominal King ...

until his execution by Charles of Anjou in 1268. Government in Jerusalem had developed in the opposite direction to monarchies in the west. European monarchs such as St Louis, Emperor Frederick and King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 1254 ...

—contemporary rulers of France, Germany and England respectively—were powerful with bureaucratic machinery for administration, jurisdiction and legislation. Jerusalem had a royalty without power.

The third invocation of the followed the Ibelin's fight for control with an Italian army led by Frederick's viceroy Richard Filangieri

Richard (Riccardo) Filangieri (''c''.1195–1254/63) was an Italian nobleman who played an important part in the Sixth Crusade in 1228–9 and in the War of the Lombards from 1229–43, where he was in charge of the forces of Frederic ...

in the War of the Lombards

The War of the Lombards (1228–1243) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Cyprus between the "Lombards" (also called the imperialists), the representatives of the Emperor Frederick II, largely from Lombardy, and the ...

. Filangieri besieged John of Beirut's city and convened the High Court to confirm his appointment as regent. When the court demanded he lift the siege, Filangieri implied John had committed treason, and if the court disagreed they should write to the Emperor for final judgement. Tyre, the Hospitallers

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

, the Teutonic Knights and the Pisans supported Filangieri. In opposition were the Ibelins, Acre, the Templars

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a military order of the Catholic faith, and one of the most important military orders in Western Christianity. They were founded in 11 ...

and Genoa. The rebels established a surrogate commune, or parliament in Acre. The commune was developed from the confraternity of St Andrew. It had its own bell and officers. The most important was the major, a position for which John of Beirut was chosen. There was also a deputy major, consuls and captains. Membership was open to all free men. While the commune presented itself as representing the whole country, it did not even represent all of Acre, and large numbers still supported the Emperor. After 1236, there is little written evidence of the commune's activities and it is clear that it never adopted governmental functions. The main objective seems to have been an attempt to match Filangieri's mandate and resist Frederick II. Ultimately, the barons' motivation resulted from Filangieri rejecting the invocation of the ''Assise''. The Barons withdrew their service and attempted to use force, but this was ineffective. Filangieri's Italian army was more than capable of resisting. This demonstrated the weakness in the Baron's case. The ''Assise'' relied on the king being weak, with a strong force of what John called ''foreign people'' or mercenaries supporting the monarchy the ''Assise'' could not be enforced. The baronial jurists such as Philip of Novara

Philip of Novara (c. 1200 – c. 1270) was a medieval historian, warrior, musician, diplomat, poet, and lawyer born at Novara, Italy, into a noble house, who spent his entire adult life in the Middle East. He primarily served the Ibelin family ...

and John of Jaffa do not mention this failure, the events of 1232 or even the bailliage of Filangieri. Instead, their impressive treatments articulated their political and constitutional ideas rather than the political reality.

See also

*Assizes of Jerusalem

The Assizes of Jerusalem are a collection of numerous medieval legal treatises written in Old French containing the law of the crusader kingdoms of Kingdom of Jerusalem, Jerusalem and Kingdom of Cyprus, Cyprus. They were compiled in the thirteent ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * {{refend Feudalism in the Kingdom of Jerusalem